1. Introduction

The Expert Group on Universities and the 2030 Agenda emphasises the importance of engaging learners with real-world challenges, encouraging experimentation, and fostering critical thinking from diverse perspectives to promote a more sustainable and equitable future (

UNESCO, 2022). These priorities have become increasingly urgent in the 2020s, as escalating geopolitical and environmental crises are reshaping migration patterns, energy security, labour markets, and policy agendas. While education alone may not solve the root causes of global challenges such as climate change and inequality, it remains pivotal in fostering learners’ resilience and skills to influence meaningful change (

OECD, 2025). Higher education institutions are therefore called to move beyond passive instruction and adopt active, adaptive pedagogies that prepare learners to navigate uncertainty and contribute to a more sustainable future.

Leading scholars on experiential and transformative learning have long critiqued traditional classroom models for their rigid structures, teacher-centred pedagogies, and emphasis on content transmission, which limit the development of complex cognitive and socioemotional skills (

A. Y. Kolb & Kolb, 2022;

Dewey, 1986;

D. A. Kolb, 1984). Such models tend to produce passive learners who struggle to engage critically with the world (

Freire, 2005, p. 81). Educating global learners requires a disposition to understand the world’s complexities and a commitment to transform reality. As

Freire (

2005, p. 85) stated, the world is not a static reality but “the object of transforming action”. Theories of experiential learning (

Dewey, 1986;

D. A. Kolb, 1984) and transformative learning (

Mezirow, 1991;

Taylor, 2007) offer complementary foundations for connecting learning processes with experience, reflection, and purposeful engagement with real-world issues.

Despite the promise of these frameworks, the literature we examined rarely provides explicit descriptions of how educators design environments that enable learners to engage with global challenges. Among the studies reviewed, experiential learning is often explored through extracurricular experiences such as service learning, internships, and study abroad programmes (

Morris, 2019;

Katula & Threnhauser, 1999), rather than through integration into formal instruction. This observation underscores the need to strengthen educators’ roles in designing experiential and transformative learning environments within the curriculum.

This study undertakes an integrative review to address the question: What characterises a learning environment for engaging learners with global challenges? Its main objective is to propose an original conceptual framework that integrates global and intercultural learning, education for sustainability, and Latin American perspectives on social engagement. To guide this inquiry, we pursue three analytical objectives: (1) identify convergences and gaps across these strands, (2) conceptualise their integration within an ecosystem perspective, and (3) discuss preliminary implications for educational design and institutional practice.

The selection of these strands responds to their frequent separation in the explored scholarship, even though they share a common concern for preparing learners to act critically in contexts where global dynamics intensify local complexities. Together, they form the analytical foundation of the proposed framework. The literature on global and intercultural learning highlights the development of global competence, civic engagement, and intercultural skills as essential for navigating an interconnected world; education for sustainability emphasises the capacities required to address complex problems and foster a greener future; and Latin American perspectives on social engagement underscore justice, equity, and collaboration with local communities, often operationalised through solidarity-based service learning. The Latin American perspective adds an original dimension to the framework, as scholarship on global learning and internationalisation has largely been shaped by Anglo-Western perspectives (

de Wit, 2019), with limited inclusion of Global South contributions that could enrich the debate, particularly in contexts where the effects of globalisation are unevenly experienced.

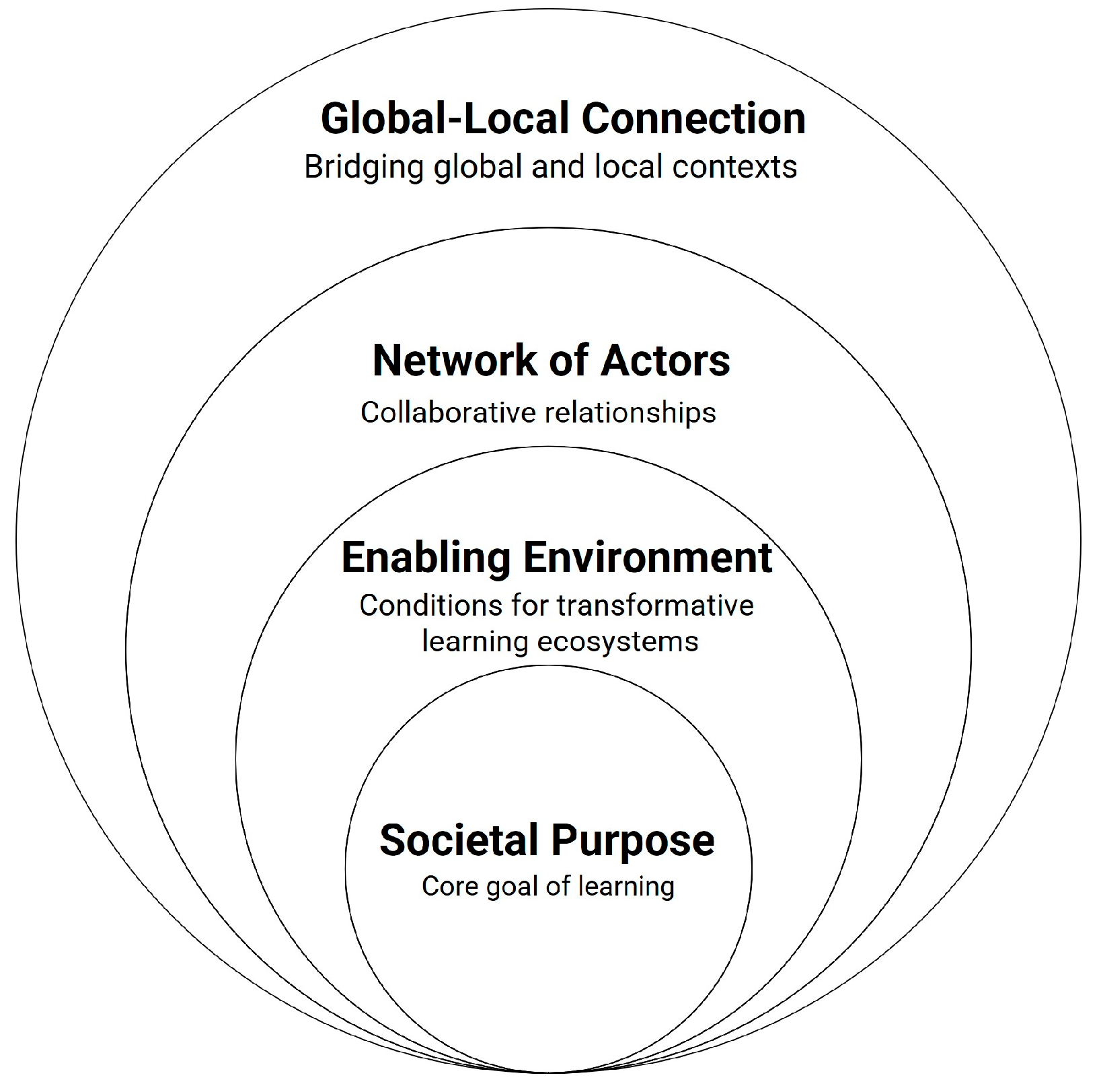

By following a critical-integrative review approach, we propose a new characterisation suitable for equipping learners to navigate global complexities in local contexts. We conceptualise it as an ecosystem with four interacting dimensions: societal purpose, enabling learning environment, network of actors, and global–local connection. This framework renews transformative education by positioning societal purpose alongside individual learning goals at the centre of educational ecosystems. Its originality lies in bridging these studies into a coherent ecosystemic framework that links individual and collective purposes, informing course-level innovation and institutional strategies for global learning.

3. Conceptual Notions

A broad body of literature focuses on the competencies learners require to navigate the complexities of a globalised world, often emphasising the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to interact across borders and contribute to global purposes. These frameworks draw from diverse disciplines and are commonly framed around terms like global citizenship (

UNESCO, 2013;

Killick, 2020;

Lilley et al., 2016;

Hunter et al., 2006;

Grad & van der Zande, 2022), intercultural competence (

Deardorff, 2006;

Byram, 1997;

Bennett, 1986), education for sustainability (

UNESCO, 2020), and global competence (

OECD, 2018). While their focus varies, these approaches emphasise learners’ capacity to address global challenges through civic engagement, shared global responsibility, and intercultural awareness.

One of the international attempts to assess both intercultural competence and the knowledge necessary to navigate globalisation from a learning perspective is the Global Competence Framework introduced in PISA 2018 (

OECD, 2018). It aims to identify knowledge, skills, attitudes and values young people need to become global citizens who contribute to Sustainable Development Goals, while generating evidence to improve curricula and teaching practices worldwide. Such competencies are not only essential for living in multicultural communities, but also for thriving in a changing labour market. However, as

Costa et al. (

2024) point out in their bibliometric analysis, the framework places a disproportionate focus on intercultural competence and civic engagement, while giving limited attention to sustainability and the complexities of socio-ecological transformation.

While many frameworks in education aim to integrate global and intercultural competencies into the local curriculum (

Leask, 2015;

Deardorff, 2011;

UNESCO, 2013), very few explicitly address how learning environments can become transformative and engage learners with the complexities of global challenges and sustainable development. In research on the internationalisation of higher education, study abroad remains the benchmark for enhancing global and intercultural competencies, considered a transformative experience that significantly shifts learners’ perspectives, attitudes, and values (

Mace, 2020;

Lilley et al., 2016;

Jones, 2013). Similarly, studies associate international experiences such as mobility, work placements, volunteering, and service learning with the development of soft skills and improved professional outcomes (

Brandenburg et al., 2017;

Bracht et al., 2006;

Jones, 2013;

Gregersen-Hermans, 2017;

Chae et al., 2020;

Wilson et al., 2013;

Pistorino, 2020).

However, such programmes rely on physical mobility, which is available to only a few and primarily involve self-directed learning (

Sercu, 2022;

Jones, 2013). This limitation has sparked interest in internationalisation at home (IAH) and internationalisation of the curriculum (IOC) strategies, which aim to integrate global, intercultural, and international dimensions into formal and non-formal curricula within domestic learning environments (

Beelen & Jones, 2015).

Despite these efforts, educational practices that foster transformative domestic experiences remain less explored. Some evidence from campus settings suggests that structured, intercultural peer interaction with international cultural diversity plays a pivotal role in developing intercultural competence, both on campus and in online settings (

Peifer et al., 2021;

Ambagts-van Rooijen et al., 2024). For example,

Membrillo-Hernández et al. (

2023) used challenge-based virtual collaboration, where Colombian and Mexican students collaborated virtually to tackle real-world problems, while parallel Latin American projects (

Ramírez, 2022;

Ermolieva, 2023;

Garza & Maher, 2022;

Martínez et al., 2023) show that combining virtual exchanges with active learning methodologies offers an accessible pathway to global and intercultural outcomes, similar to those associated with study abroad.

While some evidence shows how learning design introduces global and intercultural perspectives into the classroom, less is known about how such experiences create engaging environments where learners confront complex global challenges. Some analyses of the Internationalisation of the Curriculum point to a growing need for pedagogies grounded in cosmopolitanism, decolonisation, diversity, responsibility, social cohesion, and engagement with local communities (

Whitsed et al., 2021). However, much of the explored research on global learning and internationalisation remains limited in evidence about learning environments that move beyond intercultural and global citizenship frameworks to address societal challenges at local levels.

Educating global learners requires a disposition to understand the world’s complexities and a commitment to transform reality. In

Freire’s (

2005, p. 85) words, the world is no longer something to be described with deceptive words; instead, it becomes the object of transforming action. According to

Barnett (

2012), the world’s uncertainty requires an education that fosters adaptability, flexibility, and self-reliance. In this sense, universities should engage directly with life-world challenges and the pedagogical demands of super-complexity.

Transformative learning theory (

Taylor, 2007) highlights direct, personally engaging experiences that prompt reflection as one of the most powerful ways to foster transformation. Likewise,

Mezirow (

1991) argued that the “disorienting dilemmas” of transformational learning often change beliefs, values, and perspectives through critical reflection on experience. According to

Berger (

2004), learners shift their perspective when moved outside their comfort zone; comfort is rarely transformative. Based on the “edge of knowing” concept, educators should help learners navigate limits and question assumptions. While this process makes some learners feel frightened and unpleasant, others experience excitement at the edge of growth.

Freire (

2005) also noted that change is not possible without risk.

In his systematic review of experiential learning,

Morris (

2019) found that the majority of studies focused on out-of-classroom experiences such as service learning, internships, and study abroad programmes, highlighting elements of community engagement, challenging experiences in diverse contexts and inquiry-driven, problem- or project-based learning environments. Similar to what

Katula and Threnhauser (

1999) observed, this study also suggests the need to explore experiential learning in other classroom settings (

Morris, 2019), where it would be relevant to expand on the role of educators in creating experiential and transformative learning environments.

Despite the promise of these frameworks, in the literature we examined, practice-level descriptions of how educators create environments that enable learners to engage with global challenges were not consistently documented.

Oonk (

2016) states that addressing societal challenges requires cross-boundary collaboration between diverse stakeholders representing different practices, disciplines, and perspectives. In such multi-stakeholder learning environments, learners benefit from participating in real-world, transdisciplinary projects that bridge the gap between science and society, applying a range of approaches to tackle complex issues (

Yarime et al., 2012).

Collaborative practices such as the “Regional Learning Environment”, where learners work with multiple stakeholders toward sustainable regional transformation, sharing features with service-learning and the studio model in urban and planning studies, are most effective when they combine interdisciplinary teams, external participation, and teacher guidance to support boundary crossing (

Oonk, 2016).

Akkerman and Bakker (

2011) conceptualise boundary crossing in the realms of work, education and daily life. The value of this process lies in its potential for dialogical learning, where interaction with multiple perspectives and parties fosters new understanding. Rather than being seen as barriers, boundaries become sources of learning, driving change and development.

Akkerman and Bakker (

2011) describe boundaries as sociocultural differences that create discontinuities in interaction and action. When accompanied by reflection, boundary crossing allows individuals to view themselves through the lens of other worlds, promoting both comprehension and distinctive perspectives.

Morin’s Seven Complex Lessons in Education for the Future (

Morin, 1999) offered a vision of education capable of addressing the complexity and uncertainty of the twenty-first century. He advocated for an education that transcends the boundaries of knowledge to reveal the holistic nature of reality. Learners, he argued, must not only grasp the individual components of a problem but also understand their connections within a larger system. Central to this vision, the fourth lesson highlights the idea of a “planetary identity”, urging an education that equips individuals with ethical awareness and cognitive tools to navigate uncertainty, embrace complexity, and act as responsible citizens of a shared world. These epistemological foundations continue to inform theoretical debates in fields such as education for sustainability (

UNESCO, 2020).

In this field, a persistent concern is how to prepare learners to tackle environmental challenges that transcend local or national boundaries. Building on concepts such as learning ecologies and educational ecosystems (

Mueller & Toutain, 2015;

Barnett & Jackson, 2019;

A. Wals, 2019),

den Brok (

2018) argues that an ecosystemic approach is better suited to the evolving demands of higher education. Whereas traditional learning environments often emphasise static elements (e.g., social context or physical space), an ecosystemic perspective highlights the dynamic interactions between learners, educators, materials, and external stakeholders. Drawing on the scientific notion of ecosystem as networks of organisms and their interrelationships with the environment, authors extend the concept to include not only the internal university actors (students, staff, faculty) and external stakeholders (entrepreneurs, associations, government, companies, and families) (

den Brok, 2018). Across these sources, the emphasis lies in configuring relationships and networks so that learning operates as a systemic, interconnected and adaptive process.

Within this perspective, an educational ecosystem can be defined as a complex and adaptive system composed of learners, educators, institutions, technologies, communities and policies that interact dynamically to support learning, knowledge co-creation and innovation. (

A. E. J. Wals, 2015;

Dumont et al., 2010).

Bringing society into dialogue with academic and scientific perspectives lies at the heart of pedagogical approaches in education for sustainability. These approaches acknowledge the uncertainty and complexity of contemporary challenges, based on the premise that many of these are “wicked problems- multifaceted social or environmental issues that resist definitive solutions because they are interconnected with other problems, involve diverse stakeholders with conflicting values, and lack a clear agreed-upon definition (

Rittel & Webber, 1973). Examples include poverty, climate change, and other global sustainability challenges.

Veltman et al. (

2019) identify three defining features of wicked problems: complexity and interdependencies, uncertainty in relation to risks and consequences, and divergence in values and perspectives. While education alone cannot solve these problems, it can contribute to their mitigation by fostering adaptability, boundary crossing, and collaboration with external stakeholders (

Veltman et al., 2019). Aligned pedagogical strategies include capstone projects focused on sustainability (

Brundiers et al., 2010), transdisciplinary city collaborations (

Bohm et al., 2024), stakeholder-integrated problem-based learning, and sustainability-oriented living-labs that connect education with society (

van der Wee et al., 2024).

Empirical research on academics engaged in teaching wicked problems (

McCune et al., 2023) indicates a strong commitment to transformative teaching that integrates education, research, and action. These academics display openness to experimenting with pedagogical approaches and are less protective of the academic role as the sole authority. Their effectiveness relies on the capacity to work across disciplinary and institutional boundaries, frequently in collaboration with actors beyond academia. The study also highlights tensions within institutions where reward structures, workload models, and research expectations often undervalue boundary-crossing practices. As a result, academics pursuing this form of teaching may face risks of marginalisation and difficulties in sustaining professional identities centred on engaging with wicked problems.

Further gaps in the literature on education for sustainability have also been identified. There is a tendency to focus on transformative pedagogies primarily aimed at enhancing technical problem-solving and advancing the green economy, while often neglecting critical social dimensions such as equity, justice and community engagement.

Sterling (

2021) calls for a paradigm shift in higher education, moving beyond technical innovation to integrate social transformation and civic agency as drivers of systemic change.

A. Wals (

2019, p. 68) highlights the lack of attention to social learning aspects in sustainability programmes, particularly regarding community engagement, democracy, and social justice, noting that such programmes often prioritise technical and employability skills. Even in recent analyses of living-labs,

van der Wee et al. (

2024, p. 263) observe that despite their real-world orientation, these initiatives tend to maintain a narrow focus on technological and environmental issues, overlooking the integration of social justice, inclusivity, and community involvement.

Under the explored approaches, transformative education for complexity refers to learning processes that prompt individuals to question their assumptions, values and worldviews, and to develop new ways of thinking, being and acting. Such transformation supports both personal growth -grounded in professional identity development, reflection, and co-creation- (

van der Zande & van Diggelen, Forthcoming) and broader societal change. It encompasses cognitive, emotional, ethical, and action-oriented dimensions that engage learners in addressing global and local challenges.

Latin American higher education has a long tradition of integrating democracy, solidarity, and social justice at the core of the institutional mission.

Munck et al. (

2023) argue that civic engagement, university extension, service learning, and knowledge co-creation are not peripheral projects within institutions but an expression of the democratic mission and civic engagement across HEIs in the region. They illustrate concrete cases across universities in Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Brazil, and the Caribbean. Such programmes involve a strong sense of community engagement, bridging the gap between science, education, and societal challenges.

One of the most institutionalised practices in the region is solidarity-based service-learning. It is generally known by different names depending on the country: university community work in Costa Rica, Social Practice in Colombia, Educational Volunteering in Brazil, Solidarity Service Learning in Chile, Curricular Social Service or Service Learning in Mexico, and Educational Social Practices in Argentina (

McIlrath et al., 2012). Solidarity, the core principle in Latin America, differs from charity, altruism or paternalism: it shifts the focus from giving to sharing, from doing for others to doing with others, rooted in fairness and social justice (

N. Tapia et al., 2024;

Giorgetti, 2024;

Gonzalez, 2024). At the heart of this approach lies a tension between traditional models, based on the unilateral transmission of knowledge from universities to communities, and alternative models that promote reciprocity and knowledge exchange between universities and societal actors (

Peters, 2017).

M. N. Tapia (

2012) describes how Renewable Energy students at the National University of Salta (Argentina) design, build and install solar panels and ovens in remote Andean communities, training residents in their maintenance. The three main components of service learning are solidarity-based service, learner involvement, and community collaboration. Programmes focus on addressing real community needs through joint problem analysis and action, with the community acting as co-participants rather than passive recipients. Learners are involved in every stage, from planning to evaluation, fostering both learning and social engagement. Projects usually emphasise collaboration with local organisations, ensuring shared responsibility in addressing regional challenges (

M. N. Tapia, 2012). Unlike in the English-speaking world, where service learning is often viewed as experiential learning that enhances personal skills, Latin American service learning emerged primarily to address pressing social issues, such as poverty and inequality, situating the societal problem at the core of the experience. The urgency to create sustainable solutions for real-world problems requires multidisciplinary knowledge. This approach forms a virtuous circle where systematic learning improves the quality of social activity, and service learning stimulates further knowledge production (

M. N. Tapia, 2012).

Another key Latin American perspective emphasises equity, justice, and the recognition of local knowledge systems, rooted in Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and other historically marginalised communities. Intercultural education (

Vargas, 2008;

Duran González et al., 2019), drawing on de Sousa Santos’ “ecologies of knowledge” (2014), advocates for a horizontal dialogue between knowledge systems, challenging the dominance of Western paradigms. Similarly,

Freire’s (

2005) “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” foregrounds critical reflection, transformation, and the role of learners as active agents grounded in their social realities. From this perspective, local knowledge and critical engagement with the socio-economic asymmetries embedded in global and local dynamics are central. Together, these approaches call for a critical, intercultural and decolonial pedagogical praxis (

Walsh, 2010).

4. Bridging Notions Together

The concepts of international, global, and intercultural learning emphasise the significance of engaging with diversity, whether international or local, as a means of fostering intercultural competence. Alongside this lies the aspiration to cultivate global citizenship, understood as a commitment to and agency in shared global causes and civic responsibility. Together, these approaches aim to equip learners with the skills necessary to navigate an interconnected world and thrive in multicultural contexts. Initiatives that engage learners with global issues locally, without requiring travel abroad, highlight the importance of making such experiences accessible to all.

Education for sustainability, particularly in dialogue with transformative learning, foregrounds the imperative of preparing learners to address complexity and uncertainty in dealing with “wicked problems” that are ecological, social, and economic in nature. This perspective advances the notion of learning ecosystems, understood in this article (following Barnett & Jackson; Wals; den Brok) as configured networks of dynamic relationships, roles, and resources among stakeholders within and outside the university. Beyond the traditional triad of teacher, materials, and learner, this approach views learning as systemic and adaptive, illustrated through examples such as boundary crossing, city-university collaboration, living-labs, and online collaborations with international peers and local partners to indicate how such ecosystems are enacted in practice.

Latin American perspectives on social engagement, particularly where service-learning is institutionally embedded, highlight the need to place societal problems at the heart of educational experiences. They promote multidisciplinary collaboration to address inequality and poverty, engaging learners directly in this process. From this standpoint, systematic learning processes enhance the quality of social action, while service-learning, in turn, contributes to new knowledge production.

Across these three bodies of literature, a shared concern emerges: the preparation of learners to navigate complex contexts that demand active engagement and the capacity to generate positive societal impact. In particular, both Latin American perspectives on social engagement and the field of education for sustainability emphasise the mobilisation of learners in collaboration with external actors and communities to pursue shared purposes. Addressing today’s environmental and social demands requires interdisciplinary collaboration where global–local and intercultural perspectives play a central role.

In synthesis, the three strands converge around the notion that meaningful learning emerges from engagement with societal issues in context. Global-intercultural learning contributes to intercultural and civic dimensions of global competence; education for sustainability contributes to the systemic and interdisciplinary orientation toward complexity; and Latin American perspectives are grounded both within solidarity and social justice traditions. Their intersection defines the contours of the proposed ecosystem framework.

Towards an Integrative Framework of Global and Local Ecosystems for Societal Purpose

To address the question of what characterises a learning environment that engages learners with global challenges, we have examined three major bodies of literature: studies on global and intercultural learning, education for sustainability and Latin American approaches to social engagement. Although they share common conceptual aims, they have primarily been treated in isolation, missing the opportunity for a more integrative approach. As argued in the introduction, higher education faces an urgent demand to respond to global challenges, yet institutional responses remain tentative. Meeting this demand requires a shift toward a framework that makes education more relevant and contextually aligned.

Building on these theoretical foundations, we propose a framework grounded in learning ecosystems to address the “wicked problems” of contemporary global challenges, which are simultaneously environmental, economic, and social. A learning ecosystem refers to the interconnected system of actors, relationships, environments and resources that shape educational and knowledge creation processes. It emphasises interdependence, context and collaboration among formal and informal learning environments. An ecosystemic approach views a learning environment not as the sum of its parts, but as a dynamic set of relationships among its actors and elements. It recognises that learning does not occur in isolation but rather emerges through relationships and networks. In such ecosystems, learners encounter not only the individual components of a problem but also their interconnections within a broader system (

Morin, 1999). Rather than being treated as separate elements, these components interact dynamically, shaping the ecosystem as a whole. Together, these four interrelated dimensions constitute the ecosystem that creates conditions for meaningful learning: societal purpose, enabling learning environment, network of actors, and global–local connection. See

Figure 1.

At the core of this ecosystem lies the

societal purpose, understood in its broadest sense, as an intentional contribution to the common good and collective wellbeing. It encompasses commitment to social justice, environmental sustainability, and inclusive development at both local and global levels. This purpose represents the motivation to generate positive societal change and can take different forms depending on the problem addressed. It acts as the driving force that mobilises the ecosystem’s actors. At the same time, each actor brings distinct values and perspectives on the problem itself (

Veltman et al., 2019). The shared commitment to a societal purpose channels these differences toward potential solutions. Drawing on Latin American experiences of social engagement, purpose is grounded in societal needs, framing responses not merely as technical but also as social, particularly in contexts marked by poverty and inequality. By placing societal purpose at the centre, learning moves beyond individual competence to a collective process that creates value. It becomes a collective endeavour in which the significance lies not only in what each learner acquires but also in the shared value co-constructed with others. This reorientation requires interdisciplinary and horizontal collaboration where local communities are recognised as co-creators of solutions alongside academic communities and other stakeholders. In this sense, education transcends disciplinary boundaries of knowledge to reveal the interdisciplinary nature of reality (

Morin, 1999). Preparing learners with the skills and competencies to tackle complex challenges requires an intentional commitment to transforming surrounding realities. This commitment should be embedded in the configuration of educational ecosystems.

For the purpose to be realised, it must be situated within an

enabling learning environment, where academics and institutions facilitate transformative educational experiences. Such environments foster adaptability, flexibility, and self-reliance (

Barnett, 2012) while supporting learners in navigating uncertainty through experiential pedagogies. An enabling environment goes beyond the student-teacher-materials triad, opening the classroom to broader collaboration across physical, institutional, national, disciplinary, and cultural boundaries. In this sense, the ecosystem systematically integrates experiential methods with spaces that encourage collaboration, dialogue, and boundary crossing among diverse stakeholders. The value of this process lies in its potential for dialogical learning, where interaction with multiple perspectives fosters new understanding. Boundaries, rather than being seen as barriers, become sources of learning that drive change and development (

Akkerman & Bakker, 2011).

The enabling learning environment necessarily relies on academics who demonstrate a strong commitment to transformative teaching, intertwining education, research, and action, while remaining open to experimenting with pedagogical approaches. These academics work across disciplinary, institutional and national boundaries, and share authority through horizontal learning processes. Within this context, institutions play a pivotal role. Universities need to recognise and support these academic identities by adapting reward systems and workload models that sustain innovative teaching practices (

McCune et al., 2023).

Wicked problems cannot be addressed in isolation or from a single perspective. By their nature, global challenges are interdependent and demand contributions from multiple actors and disciplines. In an ecosystemic view, stakeholder interaction is essential, not optional. A deliberately integrated network of actors is therefore required.

These networks create conditions for cross-boundary collaboration between diverse stakeholders representing different practices, disciplines, and perspectives (

Veltman et al., 2019). The actors may include local vulnerable communities, social organisations, public institutions, companies, or even international peers. In these multi-stakeholder environments, learners engage in real-world, transdisciplinary projects that bridge science and society, applying diverse approaches to complex issues (

Yarime et al., 2012).

Notably, the ecosystemic approach shifts the relationship between universities and external actors away from a unidirectional model of knowledge transmission. Instead, it fosters reciprocity and mutual exchange, where knowledge circulates among all participants (

Peters, 2017). This approach strengthens horizontal interdisciplinary collaboration with all actors co-designing and executing solutions. In Latin American perspectives on social engagement, collaboration with local organisations ensures a shared responsibility in addressing regional challenges (

M. N. Tapia, 2012). Within this perspective, the emphasis is placed on doing something with someone, grounded in a sustained pursuit of societal purpose (

N. Tapia et al., 2024;

Giorgetti, 2024;

Gonzalez, 2024).

Finally, the

Global–Local dimension highlights the interdependence between local contexts and global processes, underscoring the need to integrate this dimension when building educational ecosystems. The global–local dimension of a learning ecosystem refers to the interdependence and mutual enrichment between globally shared knowledge, competencies, and challenges and locally grounded experiences, cultures, and needs that shape educational practices and outcomes. (

Henao-Romero et al., 2026) Contemporary challenges, such as the climate crisis, migration, and inequality, form part of a global agenda not only because they are pressing issues with consequences across multiple regions, but also because responses to “wicked problems” require shared responses and purposeful international and intercultural collaboration. In our framework, the global–local dimension is a core design element embedded in learning outcomes, materials, activities, and assessments that link local issues to global frameworks which allow structuring interaction with external partners (

Leask, 2015;

Deardorff, 2006;

OECD, 2018;

Bohm et al., 2024;

van der Wee et al., 2024;

Ramírez, 2022;

Membrillo-Hernández et al., 2023). (See

Supplementary Materials for GL inclusion).

The more a local challenge is informed by a critical understanding of global systems, the more sustainable and contextually relevant the solution can become. This approach calls for integrating diverse local knowledge sources into educational ecosystems, particularly those rooted in local communities and cultures (

Walsh, 2010;

de Sousa Santos, 2014). At the same time, it acknowledges the opportunities created by international collaboration, including the sharing of knowledge across borders, the generation of innovative perspectives on complex problems, and the embracing of collective responsibility for both risks and consequences.

While education for sustainability has emphasised a “planetary identity” focused on environmental and economic dimensions, and global-intercultural learning has highlighted the development of competences through engagement with cultural diversity, these perspectives have often evolved in parallel rather than in dialogue. Integrating the global–local dimension within the ecosystem framework enables these approaches to intersect, situating local societal challenges as entry points for global learning. In this way, educational ecosystems can generate practices that are both contextually grounded and systematically connected, contributing to broader transformations at the interface of local relevance and global interdependence.

5. Reflections and Future Directions

Acknowledging that Agenda 2030 and today’s challenges call on higher education institutions to adopt a more engaging and transformative role, this article raises the question of what characterises a learning environment for engaging learners with global challenges. To respond, we developed an integrative review and critical analysis that bridges three bodies of literature often studied separately: global and intercultural learning, education for sustainability and Latin American approaches to social engagement.

Based on the concept of educational ecosystems, we highlight how learners engage with problems and their interconnections within dynamic systems of diverse actors. We propose an integrative framework that recognises the complexity and the uncertainty inherent in “wicked” problems. The framework identifies four interrelated dimensions: societal purpose, enabling environment, network of actors, and global–local connection.

Inspired by the Latin American long-standing tradition of social engagement, the framework centres societal purpose in transformative educational design within an ecosystemic approach. Positioning societal purpose at the core mobilises the ecosystem towards generating value for all participant actors. It increases the relevance of learning and fosters co-creation of solutions to pressing societal problems.

The broader aim of this framework is to inspire academics and institutions to design educational models that place societal purposes at the core, equipping learners with the capacities necessary to navigate the complexity and interconnectedness of global and local problems. It also offers a reference point for societal actors collaborating with universities, encouraging them to join in co-constructing solutions to today’s pressing issues.

The framework is adaptable across institutional and individual levels. At the institutional level, it can guide curriculum design, policy support, and strategic initiatives aligned with societal purpose. At the course or module level, it can support academics seeking to break down the walls of the classroom and foster broader ecosystems of collaboration. The framework is not a checklist of separate elements, but an integrative approach where the four dimensions—societal purpose, enabling learning environment, network of actors, and global–local connection—interact to create meaningful and collective learning.

Looking ahead, this framework opens possibilities for further reflection and action within higher education. At the institutional level, it highlights the importance of creating conditions that enable academics who engage in boundary-crossing, transformative practices to balance these commitments with existing structures of teaching and research. Future studies should explore how institutions can recognise and support academics working within learning ecosystems. Key enablers include incentives, workload distribution, and evaluation systems that value such practices. At the same time, it calls for more empirical exploration of how the four elements interact in different contexts. This includes understanding the institutional barriers that limit their creation and developing approaches to evaluate their effectiveness at both the institutional and learner levels.

Rather than offering definitive answers, the framework invites dialogue and inquiry on how higher education can better contribute to tackling global and local challenges.