Early Intervention Strategies for Language and Literacy Development in Young Dual Language Learners: A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Dual Language Learners in Early Childhood

1.1. Theoretical Framework

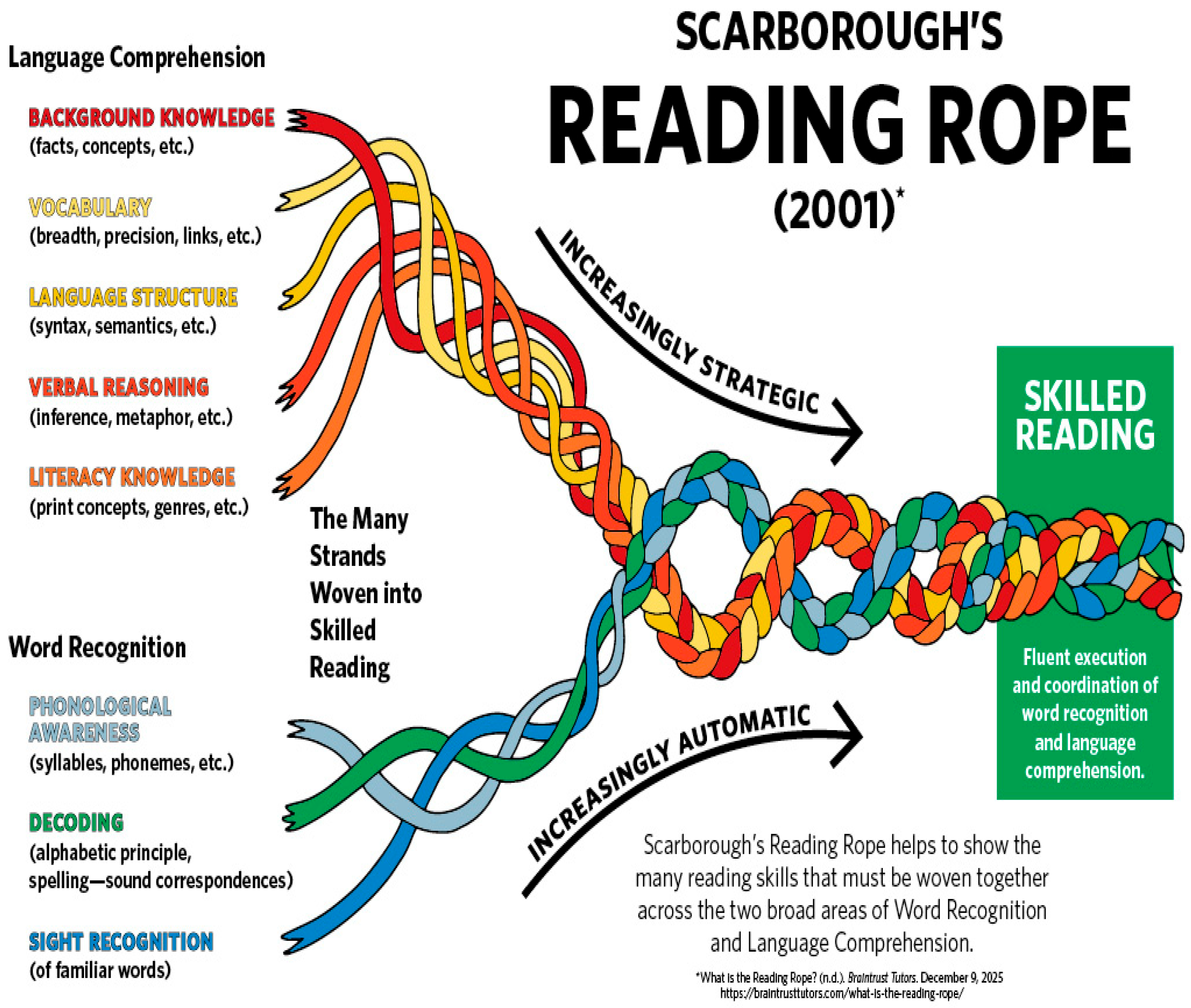

1.1.1. Simple View of the Reading

1.1.2. Theory of Second Language Acquisition

2. Literature Review Search Procedures

2.1. Literature Review Purpose

- What is the trend in published, peer-reviewed intervention research in the last 20+ years for young DLLs aged birth–five years who have or are at risk for language impairment?

- What evidence-based intervention research has been conducted with young DLLs from birth through five years of age with disabilities involving families and caregivers?

- What culturally relevant strategies from these studies can be recommended for future research and practices concerning young DLLs?

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- They were not empirically based research focusing on children’s language and linguistic development from birth to five years in the past 20 years.

- If the studies included children going to kindergarten.

- If the study participants were solely parents and caregivers and the children were not involved in the intervention.

2.2.1. Database Search

2.2.2. Ancestral Search

2.2.3. Manual Search

3. Literature Review Results

3.1. Intervention Description and Characteristics

3.1.1. Country/Ethnicity

3.1.2. Type of Disabilities

3.1.3. Research Design

3.2. Intervention Strategies

3.2.1. Theme 1: Caregiver-Based Strategies

3.2.2. Theme 2: Language Intervention Strategies

3.2.3. Theme 3: Interactive Strategies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study | Year | Title | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hargrave and Sénéchal (2000) | 2000 | A Book Reading Intervention with Preschool Children Who Have Limited Vocabularies: The Benefits of Regular Reading and Dialogic Reading | Four weeks |

| Bernhard et al. (2006) | 2006 | Identity Texts and Literacy Development among Preschool English Language Learners: Enhancing Learning Opportunities for Children at Risk for Learning Disabilities | 12 weeks |

| Roberts (2008) | 2008 | Home Storybook Reading in Primary or Second Language With Preschool Children: Evidence of Equal Effectiveness for Second-Language Vocabulary Acquisition | 12 weeks |

| Farver et al. (2009) | 2009 | Effective Early Literacy Skill Development for Young Spanish-Speaking English Language Learners: An Experimental study of two methods | 21 months |

| V. F. Gutiérrez-Clellen and Simon-Cereijido (2009) | 2009 | Using Language Sampling in clinical assessments with bilingual children: Challenges and future directions | Six weeks |

| Tsybina and Eriks-Brophy (2010) | 2010 | Bilingual Dialogic Book-Reading Intervention for Preschoolers with Slow Expressive Vocabulary Development | Six weeks |

| Pham et al. (2011) | 2011 | Addressing clinician-client mismatch: a preliminary intervention study with a bilingual Vietnamese-English preschooler | Six months |

| V. Gutiérrez-Clellen et al. (2012) | 2012 | Predictors of Second Language Acquisition in Latino Children with Specific Language Impairment | Six weeks |

| Restrepo et al. (2013) | 2013 | The Efficacy of a Vocabulary Intervention for Dual-Language Learners With Language Impairment. | 12 weeks |

| Simon-Cereijido et al. (2013) | 2013 | Predictors of growth or attrition of the first language in Latino children with specific language impairment | Three years |

| Simon-Cereijido and Gutiérrez-Clellen (2014) | 2014 | Bilingual education for all: Latino dual language learners with language disabilities | Nine weeks |

| Huennekens and Xu (2016) | 2016 | Using Dialogic Reading to enhance emergent literacy skills of young dual language learners | Six weeks |

| Méndez and Simon-Cereijido (2019) | 2019 | A View of the Lexical-Grammatical Link in Young Latinos With Specific Language Impairment Using Language-Specific and Conceptual Measures | Six weeks |

| Zhou et al. (2019) | 2019 | An exploratory longitudinal study of social and language outcomes in children with autism in bilingual home environments. | Three months |

| Pérez et al. (2021) | 2021 | Effects of Computer Training to Teach Spanish Book-Sharing Strategies to Mothers of Emergent Bilinguals at Risk of Developmental Language Disorders: A Single-Case Design Study | Six weeks |

| Rollins et al. (2022) | 2022 | Pragmatic contributions to early vocabulary and social communication in young autistic children with language and cognitive delays | Eight weeks |

| Study | Age of Child Participant (Infant/Toddler, Preschool) | Adult Participants, If Any (Family, Caregivers) | If the Study Included Child with Disability | Age Range of Child Participants | Child Gender | Country | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hargrave and Sénéchal (2000) | Preschool | Yes, parents | Specific Language Impairment and learning disability | 3–5 years | 36 children (21 girls and 15 boys) | Canada | Latino |

| Bernhard et al. (2006) | Preschool | Yes, parents | Yes Speech and language disabilities | M = 37.3 months at pretest and M = 48.4 months at posttest | 367 children (188 boys and 179 female) | USA | Hispanic/Latino African American Caucasian Other/Haitian |

| Roberts (2008) | Preschool | Yes, parents | Yes, Dual language learners with hearing difficulties | M = 52.13 months | 33 children (17 girls and 16 boys) | USA | Hmong and Spanish |

| Farver et al. (2009) | Preschool | Yes, mothers | Yes, Speech and language delays | M age = 54.51 months | 43 girls | USA | Spanish |

| V. F. Gutiérrez-Clellen and Simon-Cereijido (2009) | Preschool | Yes, parents | Specific Language impairment | Four years of age | 113 (41 boys and 72 girls) | USA | Mexican American |

| Tsybina and Eriks-Brophy (2010) | Preschool | Yes, mothers | Yes, Preschool children with expressive vocabulary delays | 22–42 months | 12 children (2 girls and ten boys) | Canada | Latino |

| Pham et al. (2011) | Preschool | No | Yes, moderate to severe impairment | Three years 11 months | 1 Boy | USA | Asian American (Vietnamese) |

| V. Gutiérrez-Clellen et al. (2012) | Preschool | NO | Specific Language impairment | 4 years of age | 113 (41 boys and 72 girls | USA | Hispanic |

| Simon-Cereijido et al. (2013) | Preschool | NO | Specific Language impairment | Four years of age | 185 children (113 boys and 72 girls) | USA | Latino |

| Restrepo et al. (2013) | Preschool | Yes, parents | Yes, specific language impairment | 48 to 64 months | 54 children (22 boys and 32 girls) | USA | Spanish |

| Simon-Cereijido and Gutiérrez-Clellen (2014) | Preschool | Yes, parents | Yes, Dual language learners with Language impairment | VOLAR group (mean = 53 months, SD = 4 months) control group (mean = 53 months, SD = 3 months) | Group 1: 60 children (29 boys and 31 girls) Group 2: 47 children (26 boys and 21 girls) | USA | Spanish |

| Huennekens and Xu (2016) | Preschool | Yes, parents | Yes, Dual language learners with Language impairment | 4 to 5 | 15 participants, boys, and girls | mid-Atlantic, urban school district | Spanish |

| Méndez and Simon-Cereijido (2019) | Preschool | Yes, parents | Yes, Specific Language Impairment | 2–4 years | 74 participants, 40 boys, and 34 girls | USA | Latino |

| Zhou et al. (2019). | Preschool | Yes, parents | Yes, Autism spectrum disorder | 2–3 years | 98 participants (more male participants than women) | USA | Spanish, Ukrainian Portuguese Japanese Vietnamese Chinese Tigrinya Romanian Hindi German |

| Pérez et al. (2021). | Preschool | Yes, mother | Yes, Developmental language disorder | 2–5 years old | Six children and six mothers | USA | Spanish |

| Rollins et al. (2022). | Preschool | Yes, parent | Yes, Autism spectrum disorder | 18–57 months | 56 children (M = 35.7 months, SD = 10.3 months) | USA | Asian, Black/African American |

| Study | Year | Title | Journal | Intervention Included? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hargrave and Sénéchal (2000) | 2000 | A Book Reading Intervention with Preschool Children Who Have Limited Vocabularies: The Benefits of Regular Reading and Dialogic Reading | Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research | Yes |

| Bernhard et al. (2006) | 2006 | Identity Texts and Literacy Development among Preschool English Language Learners: Enhancing Learning Opportunities for Children at Risk for Learning Disabilities | Teachers College Record, Columbia University | Yes |

| Roberts (2008) | 2008 | Home Storybook Reading in Primary or Second Language With Preschool Children: Evidence of Equal Effectiveness for Second-Language Vocabulary Acquisition | Research Reading Quarterly | Yes |

| Farver et al. (2009) | 2009 | Effective Early Literacy Skill Development for Young Spanish-Speaking English Language Learners: An Experimental study of two methods | Child Development | Yes |

| V. F. Gutiérrez-Clellen and Simon-Cereijido (2009) | 2009 | Using Language Sampling in clinical assessments with bilingual children: Challenges and future directions | Seminars in Speech and Language | Yes |

| Tsybina and Eriks-Brophy (2010) | 2010 | Bilingual Dialogic Book-Reading Intervention for Preschoolers with Slow Expressive Vocabulary Development | Journal of Communication Disorders | Yes |

| Pham et al. (2011) | 2011 | Addressing clinician-client mismatch: a preliminary intervention study with a bilingual Vietnamese-English preschooler | Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools | Yes |

| V. Gutiérrez-Clellen et al. (2012) | 2012 | Predictors of Second Language Acquisition in Latino Children with Specific Language Impairment | American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology | Yes |

| Restrepo et al. (2013) | 2013 | The Efficacy of a Vocabulary Intervention for Dual-Language Learners With Language Impairment. | Journal of Speech, Language & Hearing Research | Yes |

| Simon-Cereijido et al. (2013) | 2013 | Predictors of growth or attrition of the first language in Latino children with specific language impairment | Applied Psycholinguistics | Yes |

| Simon-Cereijido and Gutiérrez-Clellen (2014) | 2014 | Bilingual education for all: Latino dual language learners with language disabilities | International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism | Yes |

| Huennekens and Xu (2016) | 2016 | Using Dialogic Reading to enhance emergent literacy skills of young dual language learners | Early Child Development and Care | Yes |

| Méndez and Simon-Cereijido (2019) | 2019 | A View of the Lexical-Grammatical Link in Young Latinos With Specific Language Impairment Using Language-Specific and Conceptual Measures | Journal of Speech, Language & Hearing Research | Yes |

| Zhou et al. (2019) | 2019 | An exploratory longitudinal study of social and language outcomes in children with autism in bilingual home environments. | Autism | Yes |

| Pérez et al. (2021) | 2021 | Effects of Computer Training to Teach Spanish Book-Sharing Strategies to Mothers of Emergent Bilinguals at Risk of Developmental Language Disorders: A Single-Case Design Study | American Speech and Language Hearing | Yes |

| Rollins et al. (2022) | 2022 | Pragmatic contributions to early vocabulary and social communication in young autistic children with language and cognitive delays | Journal of Communication Disorders | Yes |

References

- Bernhard, J. K., Winsler, A., Bleiker, C., Ginieniewicz, J., & Madigan, A. L. (2006). Read my story! Using the early authors program to promote early literacy among diverse, urban preschool children in poverty. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. (2018). Bilingual education for young children: Review of the effects and consequences. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(6), 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braintrust Tutors. (n.d.). Waht is the reading rope? Available online: https://braintrusttutors.com/what-is-the-reading-rope (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Braun, G., Kumm, S., Brown, C., Walter, S., Hughes, M. T., & Maggin, D. M. (2020). Living in tier 2: Educators’ perceptions of MTSS in urban schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(10), 1114–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, L. K., Hartzheim, D., Lund, E. M., Simonsmeier, V., & Kohlmeier, T. L. (2016). Bilingual and home language interventions with young dual language learners: A research synthesis. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 47(4), 347–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farver, J. A. M., Lonigan, C. J., & Eppe, S. (2009). Effective early literacy skill development for young Spanish—Speaking English language learners: An experimental study of two methods. Child Development, 80(3), 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foorman, B., Dombek, J., & Smith, K. (2016). Seven elements important to successful implementation of early literacy intervention. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 154, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, S., Bowyer-Crane, C., Haley, A. J., Hulme, C., & Snowling, M. J. (2013). Efficacy of language intervention in the early years. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(3), 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gándara, P., & Escamilla, K. (2016). Bilingual education in the United States. In O. García, A. M. Y. Tse, & J. K. Gutiérrez (Eds.), Bilingual and multilingual education (pp. 1–14). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiberson, M. M., & Ferris, K. P. (2019). Early language interventions for young dual language learners: A scoping review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 28(3), 945–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Clellen, V., Simon-Cereijido, G., & Sweet, M. (2012). Predictors of second language acquisition in Latino children with specific language impairment. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21(1), 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Clellen, V. F., & Simon-Cereijido, G. (2009). Using language sampling in clinical assessments with bilingual children: Challenges and future directions. Seminars in Speech and Language, 30(4), 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, C. S., Hoff, E., Uchikoshi, Y., Gillanders, C., Castro, D. C., & Sandilos, L. E. (2014). The language and literacy development of young dual language learners: A Critical Review. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 715–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargrave, A. C., & Sénéchal, M. (2000). A book reading intervention with preschool children who have limited vocabularies: The benefits of regular reading and dialogic reading. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(1), 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huennekens, M. E., & Xu, Y. (2016). I am using dialogic reading to enhance the emergent literacy skills of young dual-language learners. Early Child Development and Care, 186(2), 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelin, V. C., Saluja, S., Bosak, D. L., Anaby, D., Werler, M., & Khetani, M. A. (2024). Caregiver strategies supporting community participation among children and youth with or at risk for disabilities: A mixed-methods study. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 12, 1345755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamhi, A. G. (2007). The role of the speech-language pathologist in providing intervention for reading problems. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 38(1), 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keffala, B., Scarpino, S., Scheffner Hammer, C., Rodriguez, B. L., Lopez, L., & Goldstein, B. (2020). Vocabulary and phonological abilities affect dual language learners’ consonant production accuracy within and across languages: A large-scale study of 3- to 6-year-old Spanish-English dual language learners. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(3), 1196–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krashen, S. D. (1998). Comprehensible output? System, 26(2), 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z., McClelland, M. M., & Gunderson, L. (2023). Dual language learners: Influence of parent education & mobility on school readiness. Applied Developmental Science, 27(3), 101605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonigan, C. J., Burgess, S. R., & Schatschneider, C. (2022). Word reading and language comprehension: Separating and integrating components of reading. Scientific Studies of Reading, 26(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez, L. I., & Simon-Cereijido, G. (2019). A view of the lexical–grammatical link in young latinos with specific language impairment using language-specific and conceptual measures. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62(6), 1775–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2021). 2021 NAEP school and teacher questionnaire special study. U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- National Conference of State Legislatures. (2022). Dual language learners and early childhood education. NCSL. Available online: https://www.ncsl.org (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Park, M., Zong, J., & Batalova, J. (2018). Growing superdiversity among young U.S. dual language learners and its implications. Migration Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, M. V., Mancilla-Martínez, J., & Goldenberg, C. (2021). Interactive reading strategies and language development in young dual language learners. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 56, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, G., Kohnert, K., & Mann, D. (2011). Addressing clinician-client mismatch: A preliminary intervention study with a bilingual Vietnamese-English preschooler. Language, Speech & Hearing Services in Schools, 42(4), 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, M. A., Morgan, G. P., & Thompson, M. S. (2013). The efficacy of a vocabulary intervention for dual-language learners with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 56(2), 748–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, T. A. (2008). Home storybook reading in primary or second language with preschool children: Evidence of equal effectiveness for second—Language vocabulary acquisition. Reading Research Quarterly, 43(2), 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins, P. R., De Froy, A. M., Gajardo, S. A., & Brantley, S. (2022). Pragmatic contributions to early vocabulary and social communication in young autistic children with language and cognitive delays. Journal of Communication Disorders, 99, 106243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. B. Neuman, & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for research in early literacy (pp. 97–110). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, R. E. (2019). Stephen Krashen’s theory of second language acquisition. English Made in Brazil. Available online: https://www.sk.com.br/sk-krash-english.html (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Senthamarai, S. (2018). Interactive teaching strategies. Journal of Applied and Advanced Research, 3(1), S36–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Cereijido, G., & Gutiérrez-Clellen, V. F. (2014). Bilingual education for all: Latino dual language learners with language disabilities. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 17(2), 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Cereijido, G., Gutiérrez-Clellen, V. F., & Sweet, M. (2013). Predictors of growth or attrition of the first language in Latino children with specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics, 34(6), 1219–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsybina, I., & Eriks-Brophy, A. (2010). Bilingual dialogic book-reading intervention for preschoolers with slow expressive vocabulary development. Journal of Communication Disorders, 43(6), 538–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyer, M. (2018). Dual- and English-language learners. National Conference of Staff Legislatures. Available online: https://www.ncsl.org/research/education/english-dual-language-learners (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Zhou, V., Munson, J. A., Greenson, J., Hou, Y., Rogers, S., & Estes, A. M. (2019). An exploratory longitudinal study of social and language outcomes in children with Autism in bilingual home environments. Autism, 23(2), 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghosh, E.; Banerjee, R. Early Intervention Strategies for Language and Literacy Development in Young Dual Language Learners: A Literature Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1692. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121692

Ghosh E, Banerjee R. Early Intervention Strategies for Language and Literacy Development in Young Dual Language Learners: A Literature Review. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1692. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121692

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhosh, Ekta, and Rashida Banerjee. 2025. "Early Intervention Strategies for Language and Literacy Development in Young Dual Language Learners: A Literature Review" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1692. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121692

APA StyleGhosh, E., & Banerjee, R. (2025). Early Intervention Strategies for Language and Literacy Development in Young Dual Language Learners: A Literature Review. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1692. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121692