1. Introduction

The global COVID-19 pandemic has influenced higher education, leading to a shift towards remote learning (

Fang & Ng, 2023;

Fang et al., 2024;

Bozkurt et al., 2020;

Resch et al., 2023). This shift has exacerbated divides between countries and individuals, reflecting the growing concern of the digital divide (

Lythreatis et al., 2021;

J. Van Dijk, 2020;

Vassilakopoulou & Hustad, 2023). To address this inequality, researchers have explored the determinants of the digital divide, which can be categorized into three levels (

González-Betancor et al., 2021;

Scholkmann et al., 2024;

Tang et al., 2021). The first level consists of demographics, such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status (SES), which are unequally distributed (

Lythreatis et al., 2021;

Mathrani et al., 2022;

J. A. G. M. Van Dijk, 2017). The second level is influenced by factors like age, education, and occupation (

Aissaoui, 2022;

Scheerder et al., 2017;

A. Van Deursen & Van Dijk, 2011). The third level is primarily shaped by social (e.g., relationships) and individual (e.g., motivation) factors (

Scheerder et al., 2017;

A. J. Van Deursen & Helsper, 2015;

A. J. Van Deursen et al., 2017).

Several international institutions have reported statistical data demonstrating the global trend of the digital divide. The OECD noted in 2021 that digital divides persist between urban and rural areas in G20 nations, with the digital gap in rural areas being more significant than in metropolitan cities (

OECD, 2021). Additionally, the report found differences in digital skills between urban and rural residents across various domains. Furthermore, the

OECD’s (

2018) report highlighted the gender gap in digital technology, showing that women had less access and proficiency than men in some G20 countries.

Previous studies have examined the digital divide in higher education. For instance,

Soomro et al. (

2020) investigated

J. A. Van Dijk’s (

2005) four-gap model concerning the digital access divide among Pakistani faculty. They analyzed how personal factors (such as age, gender, and race) and positional categories (such as labor and education) influenced access to technology. Their findings revealed significant variations in teacher access to technology across the four access gaps, viewed from both positional and personal perspectives. Similarly,

Faloye and Ajayi (

2022) explored the factors contributing to the digital divide among university students in South Africa. They employed

Wei et al.’s (

2011) three-level digital divide framework to analyze the determinants affecting this divide in higher education. Their results indicated that students’ fears related to computers and the timing of technology access significantly correlated with their computer self-efficacy (digital capability). Additionally, they found that urban/rural status and family socioeconomic status (SES) also influenced the digital divide among university students.

Lembani et al. (

2020) further examined the digital divide in distance learning among 230 South African undergraduate students from urban and rural backgrounds. Their findings highlighted a clear distinction in ICT access between urban and rural students, indicating that family SES and geographical location significantly impacted the digital divide.

While educational researchers have explored the digital divide at various levels, several research gaps remain. Most studies have concentrated on the effectiveness of e-learning and student mobility, rather than addressing post-pandemic equity issues. Additionally, there is a specific lack of research on the digital divide in higher education and insufficient focus on the first and third levels of the digital divide (

Yang, 2020;

Lythreatis et al., 2021). Furthermore, existing studies often overlook the socio-demographic factors (such as gender and urban/rural status) and socioeconomic factors (such as family socioeconomic status) that contribute to the digital divide (

Álvarez-Dardet et al., 2020;

Lythreatis et al., 2021). Finally, there is a scarcity of research examining the theoretical frameworks that underpin the digital divide (

Aissaoui, 2022).

To address these research gaps, this study explored the differences in the digital divide among university students from diverse backgrounds (e.g., gender, region, family SES) and investigated university students’ perceptions of the digital divide. The findings contribute to an updated theoretical framework of the digital divide in higher education and provide practical suggestions to help minimize disadvantaged students’ digital inequalities. Accordingly, the research questions are

What are the differences in the digital divide among university students from various sociodemographic (e.g., gender, urban/rural) and socioeconomic (e.g., family SES) backgrounds?

How do university students explain their perceptions of the digital divide?

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Framework

Theoretical frameworks are essential for conceptualizing research focuses and providing structure for researchers. While existing frameworks have been useful for exploring digital inequality at educational and national levels, they often fall short of offering a comprehensive model of the digital divide. To address this gap,

Wei et al. (

2011) proposed a three-level digital divide framework that examines the digital access divide, digital capability divide, and digital outcome divide within an educational context. The digital access divide refers to the disparity between students who use computers and those who do not. This divide encompasses both home and school environments, where students access technology. Home computing includes usage for both study and leisure, while school computing involves the availability of IT resources, usage patterns, cultural factors, and the quality of training. The digital capability divide pertains to students’ confidence in their computer skills, reflecting their computer self-efficacy. The digital outcome divide captures the differences in benefits that students derive from their computer skills, which consist of knowledge outcomes (such as learning content and performance) and skills outcomes (including communication with teachers and peers). The relationships among these three levels of the digital divide are interrelated: the digital access divide influences the digital capability divide, which in turn affects the digital outcome divide. This framework has been adopted and validated by scholars studying the digital divide in various educational contexts (e.g.,

Adhikari et al., 2017;

Faloye & Ajayi, 2022).

To meet the purposes of this study, we have adapted Wei et al.’s framework to the higher education context and incorporated sociodemographic (e.g., gender, area) and socioeconomic (e.g., family SES) factors (see

Figure 1). In our adapted framework, the digital access divide encompasses home and university computing environments. The home computing environment refers to students’ use of computers for study and leisure activities. Additionally, we found that university students predominantly use their personal computers and rarely access public computers in various campus locations, including the library, classrooms, and dormitories. Therefore, the university computing environment includes these locations, and university IT resource usage covers both personal and public computers. The other components of this framework, namely the digital capability divide and digital outcome divide, remain consistent with

Wei et al.’s (

2011) original model.

2.2. Research Design

This study employed a mixed-methods explanatory sequential design, which involves the successive collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data (

Creswell, 2012). It is a two-phase model, one of the most widely used types of mixed methods design for academic research (

Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011). Specifically, the study first collected and analyzed quantitative data, followed by the collection and analysis of qualitative data. The purpose of the qualitative data collection is to provide a more in-depth explanation of the trends observed in the quantitative data. The rationale for using this research method is that it would help researchers develop a clear understanding of the research topic and identify relevant groups to conduct a deeper investigation.

2.3. Participants

China, the world’s second-largest population, faces complex social inequality issues due to unequal economic and resource distributions (

Hill & Lawton, 2018;

Song et al., 2020). This includes significant gender discrepancies, especially in major cities like Beijing and Shanghai. While urban modernization has advanced rapidly in super first-tier cities like Shenzhen, some rural or remote areas (e.g., fifth-tier cities) still lack resources such as education, technology, and medical facilities. The Chinese government has implemented digital cultivation and promoted digital equality in national education (

Xiao, 2019;

Y. Zhao et al., 2021), but the effectiveness of these policies requires further research. Moreover, China has adopted emergency measures to transition to online education in universities during the pandemic (

Yang, 2020). As students frequently use digital media in higher education due to remote learning (

Resch et al., 2023), this may influence the digital divide. Therefore, this study examines the issue of the digital divide in the context of Chinese higher education, based on the perceptions of undergraduate students from various grades and universities in Guangdong Province.

2.4. Data Collection

Prior to the formal research, we conducted a pilot study with 30 undergraduate students to assess the clarity and effectiveness of the questionnaire. We revised the questionnaire based on students’ feedback to improve its quality and clarity. This study used a random sampling method to invite undergraduate participants from twenty universities in Guangdong province to participate in this study. The questionnaire survey comprised four sections: demographic information, digital access divide, digital capability divide, and digital outcome divide. The demographic information section included age, gender, year of study, urban/rural residence, and family SES (household income, parents’ education, and occupation). The digital access divide section, adapted from previous studies (

Wei et al., 2011;

L. Zhao et al., 2010), covered home computer ownership and usage, university IT resource availability and usage, and IT training. The digital capability divide section, verified by

Cassidy and Eachus (

2002), focused on computer self-efficacy. The digital outcome divide section, based on

Wei et al. (

2011), assessed knowledge and skills outcomes. The demographic information of participants is shown in

Table 1.

We spent one month collecting questionnaire data, as we needed to approach 20 universities in Guangdong province and seek the teachers’ approval before they distributed the questionnaires to their students. We used online software to distribute the questionnaires, ultimately receiving 438 responses.

Additionally, this study used purposive sampling to select interviewees from diverse sociodemographic and socioeconomic backgrounds. We categorized the groups by combining gender, region, and family SES, resulting in eight confirmed groups. We invited two students from each group for in-depth individual interviews. Twenty interview questions were developed to further investigate the reasons behind the differences in gender, region, and family SES within the three-stage digital divide. These questions are open-ended and require detailed examples in their responses. For example, one question aimed at exploring gender differences in the digital divide asked: “As a female/male student, do you feel that your gender affects your access to computers for studying or entertainment (e.g., gender inequality, discrimination)? Can you provide examples? How does your gender influence your computer skills and confidence in using a computer?” Another question focused on regional differences in students’ digital divide: “Does the city or rural area where you live affect your access to computers for studying or entertainment (e.g., limited resources or inadequate conditions)? Can you provide examples? How does your living environment influence your computer skills and confidence in using a computer?” The researcher conducted and recorded individual interviews with 16 participants. All students volunteered to participate in this study by submitting a consent form. The distribution of the eight interviewee groups is shown in

Table 2.

2.5. Data Analysis

The quantitative data collected through questionnaire surveys were analyzed using SPSS 31 software. For the Likert-scale items, the means, standard deviations, and frequencies were calculated. The Cronbach alpha of each instrument and the loadings on the predicted factors were calculated, indicating good reliability and validity. A normal distribution was also tested to ensure the collected data could be analyzed using independent sample t-tests. The researcher then used independent sample t-tests to evaluate the differences in the three levels of the digital divide between male and female students, urban and rural students, and high-family SES and low-family SES students.

After collecting the interview data, the researcher transcribed the recordings using an intelligent verbatim transcription approach. The researcher employed a thematic analysis approach to code each transcription sentence by sentence (

Braun & Clarke, 2006), a classic and popular qualitative research method with six phases: becoming familiar with the data and finding potential points of interest, creating preliminary codes, looking for themes, evaluating probable themes, identifying and categorizing themes, and generating the text (

Braun & Clarke, 2006,

2012). Two researchers went through the six phases during the data analysis process and determined the relationships among the different themes generated from the transcriptions. They met regularly to discuss the coding results until they reached a consensus, verified by a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.9, indicating a high level of inter-rater reliability (

Watkins & Pacheco, 2000).

Finally, the researchers categorized 16 interviewees into five categories, from ‘high-high-high’ to ‘low-low-low’ (see

Table 3). For example, ‘high-high-high’ means students had sufficient digital access, strong digital capability, and good digital outcomes, while ‘low-low-low’ means students had limited digital access, weak digital capability, and poor digital outcomes.

3. Result

3.1. Effects of Sociodemographic and Socioeconomic Factors on the Digital Divide

The results of independent sample

t-tests comparing the digital divide between males and females, urban and rural students, and high-family SES and low-family SES students are presented in

Table 4.

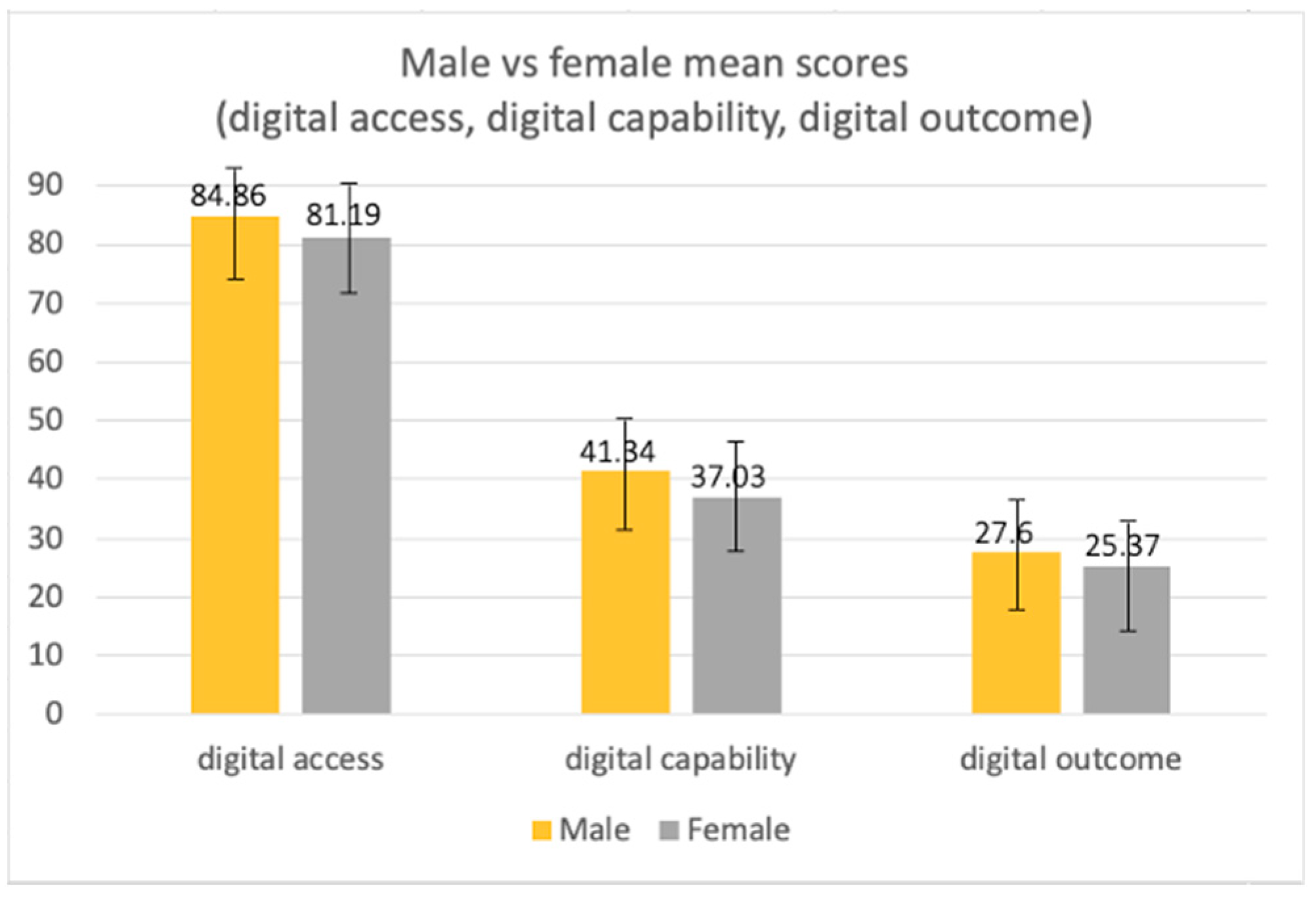

3.1.1. Gender Difference

The study included 175 (40%) male and 263 (60%) female participants in the questionnaire surveys. As shown in

Figure 2, the mean scores of the three levels of the digital divide for males were generally higher than for females. The differences in almost all contributing factors toward the three levels of the digital divide between the two tested groups were significant. However, the differences in home computer usage, university IT culture, and university IT training between the two tested groups were insignificant (

p-value range from 0.332 to 0.981, >0.05).

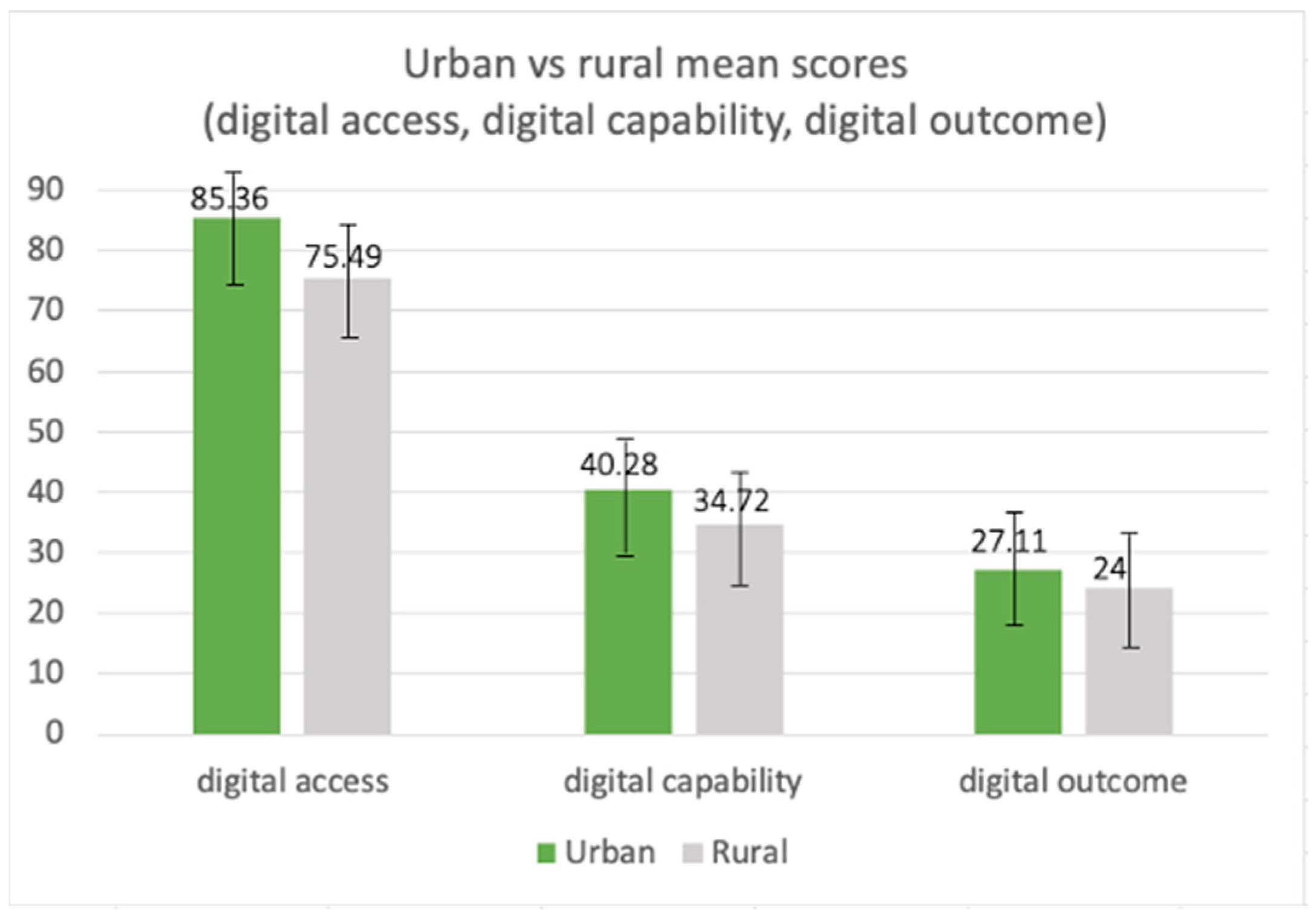

3.1.2. Regional Difference

The study included 318 (73%) urban and 120 (27%) rural students participating in the questionnaire surveys. As shown in

Figure 3, the mean scores of the three levels of the digital divide for urban students were generally higher than for rural students. The differences in all contributing factors toward the three levels of the digital divide between the two tested groups were significant.

3.1.3. Family SES Difference

The study included 116 (26.5%) high-family SES and 131 (30%) low-family SES students participating in the questionnaire surveys. As shown in

Figure 4, the mean scores of the three levels of the digital divide for high-family SES students were generally higher than those for low-family SES students. The differences in almost all contributing factors toward the three levels of the digital divide between the two tested groups were significant. However, the differences between the two tested groups in university IT resource usage and university IT training were insignificant (

p-value range from 0.098 to 0.343, >0.05).

3.2. Students’ Perspectives from a Gender Perspective

3.2.1. Digital Access

Males prefer to access computers for leisure activities, while female students prefer to access computers for study activities. Male students prefer to use computers for leisure activities such as playing digital games and engaging in online leisure pursuits. They believed they had sufficient computer access in their daily life. Harry mentioned, “I prefer to play computer games and interact online with my roommates. It is really interesting. I have freedom to access digital devices every day.”

Female students prefer to use the computer to complete study tasks, such as assignments, presentations, and group discussions. In addition to these learning activities, females rarely use the computer to learn computer knowledge and skills. Iris implied, “I usually use my computer to do my homework or prepare for exams, as these tasks were required by uploading to the assignment system. I seldom use my computer to learn new computer knowledge and skills such as programming.”

3.2.2. Digital Capability

Males have higher computer skills than females. Male students believed they had good computer skills, as they had sufficient computer knowledge, practice, and usage in their daily study and life. They were confident in using computers to address learning problems. David revealed, “I am good at computers. I feel fine when I face computer problems, as I am competent to address them using my expertise in computer usage.”

Female students demonstrated a lack of proficiency in computer skills. They had low confidence in using computers and were even afraid to learn professional knowledge in computer courses. Olivia expressed, “I am not familiar with computer usage and do not have good computer skills. Therefore, I felt unconfident when I had to learn computer knowledge in university courses and implement it in my learning tasks.”

3.2.3. Digital Outcomes

Male students had good learning abilities, while female students had limited learning abilities. Male students believed they had good communication and problem-solving skills, as they were confident in their computer skills, which helped them communicate smoothly with others and address difficulties with computer-related issues. Bob mentioned, “I am good at computer skills. It really helps with my problem-solving skills, as I know how to solve a computer error when it appears in my learning process. I can also confidently communicate with others about computer-related knowledge and ideas.”

Females thought they had low problem-solving skills and were afraid to discuss computer problems because they lacked the capability and confidence to handle these issues. Mary stated, “I do not have good computer knowledge and skills, so I am not confident to deal with computer problems and seldom talk about related topics with others.”

3.3. Students’ Perspectives from a Region Perspective

3.3.1. Digital Access

Urban areas had more sufficient digital resources and infrastructure than rural areas. Urban students believed they had sufficient opportunities to access computers, as developed areas provided a good foundation of digital infrastructure for citizens. Therefore, urban students could conveniently access advanced technologies. Cathy implied, “Living in a first-tier city like Shenzhen allows me to get in touch with computers. There are relevant courses for me to learn, and external assistance will increase my computer confidence.”

Rural areas seldom provided digital resources and computer infrastructure for local students, limiting rural students’ accessibility to computers. Fanny suggested,

“There are no places with computer equipment in rural areas, such as internet cafes. If I need to, I have to go to the city. Generally, I will not go there unless there are special circumstances, so the chance of accessing computers is much smaller.”

3.3.2. Digital Capability

Urban students had higher computer skills than rural students. Urban students believed they had strong computer skills, as their living community provided ample digital infrastructure and resources for them to access and use. Ares demonstrated, “I am confident in my computer skills as I can access digital infrastructure when I go to public places such as technology experience venues. I have the opportunity to try using advanced technology (e.g., AR, VR).”

Rural students mentioned they had limited computer skills, as their region did not provide adequate digital support for their needs, and the local school and community lacked sufficient economic means to invest in digital infrastructure. Ginny suggested, “I cannot access digital technologies in my daily life. My living community does not provide digital infrastructure for its citizens. To be honest, I feel not confident in my computer skills.”

3.3.3. Digital Outcomes

Urban students had higher competitiveness than rural students. Urban students believed they had a good competitive edge in finding a satisfactory job after graduation because they were proficient in computer usage. Bob stated, “I believe I can find a job that I am interested in, as I have sufficient experience in digital access and good practice of digital skills. This will give me an advantage in facing the highly competitive job market.”

Rural students were concerned they might not be competitive in gaining a suitable job after graduation, as they did not have strong digital capabilities and experience, which seem increasingly important in the job market. Marry mentioned, “I may not want to find a job related to computing. I do not think I learned computers well, as I did not have prior knowledge and skills in this field before I got into the university.”

3.4. Students’ Perspectives from a Family SES Perspective

3.4.1. Digital Access

High-family SES provided more sufficient digital conditions than low-family SES. Students from higher SES families had more opportunities to access computers, as their families provided sufficient conditions for their accessibility to digital devices. Ares implied,

“As someone who has had a computer at home since I was a child, computers may be a relatively common thing to me. I think family economic conditions have a positive effect on computer exposure. Because I have been exposed to this since I was a child, I have learned some operations in advance or have not been too unfamiliar, so if I reencounter it later, I would not feel that this is something completely beyond my knowledge.”

Parents from lower socioeconomic status (SES) families often had insufficient digital resources. They could not provide basic digital conditions for their children with computers and related digital resources. Peter revealed, “My family’s economic status impacts my computer access. Otherwise, my parents would not have reacted the way they did when I bought the computer four years ago. They refused to install broadband at home.”

3.4.2. Digital Capability

Students from high-family SES had higher computer skills than those from low-family SES. Students from higher SES families had confidence in their computer skills, as they had ample experience in computer access and usage. Bob demonstrated,

“I always use computers for both study and leisure activities. When I was a primary school student, my school provided iPads for our Chinese and English reading courses. I had a good foundation in computer access and usage. So, I am confident in my computer skills.”

Students from lower SES families could be affected in developing their computer skills, as they had limited access to and experience using computers at home. Emily expressed,

“Many of our classes require speeches, and our PowerPoint presentation ability is essential. There are underprivileged students in the class who have had no basic knowledge of computers since childhood, and they only come into contact with computers for the first time when they enter college. The effect of making PowerPoint presentations is relatively poor, and their computer skills are relatively limited.”

3.4.3. Digital Outcomes

Students from high-family SES had positive learning outcomes, while students from low-family SES had negative learning outcomes. Students from higher SES families believed they had good learning performance and knowledge acquisition, as they had sufficient digital devices and professional support to help them learn new digital knowledge and skills. Emily stated, “I learned much new knowledge in addition to my university curricula via using my computers and social media. This learning method really enhances my learning performance, as I can quickly search for solutions when I face problems in my studies.”

Students from lower SES families mentioned their learning outcomes did not perform as well, as they lacked experience in digital access and were limited in their digital skills to help them master a high level of knowledge and capabilities in the digitally supported learning era. Leo indicated, “It’s difficult for me to obtain proper knowledge using digital devices because I do not prefer utilizing a computer to practice knowledge and learn new digital skills. I think my limited digital experience and skills are an obstacle for me.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Gender

We examined the effects of gender, region, and SES on the three levels of the digital divide among undergraduate students. Our results showed that female students had significantly lower scores than male students at each level of the digital divide, indicating that a gender difference in the digital divide still exists among undergraduate students. As noted by

C. Guo and Wan (

2022), female students often have lower-quality digital equipment and internet access than male students, which can negatively impact their outcomes in benefiting from the internet. Additionally, the

OECD (

2023) reported that challenges such as limited access, affordability, low educational levels, and unequal social status could limit the opportunities for women and girls to access digital equipment, enhance their digital capabilities, and benefit from digital outcomes. However, we found no significant differences between female and male students in home computer usage for study, university IT culture, and IT training. This is because Chinese universities provided a policy on digital transformation education in 2016, emphasizing the equal distribution and support of digital resources in higher education. Another reason can be that the pandemic accelerated and promoted digital transformation in higher education (

Scholkmann et al., 2024).

In addition, male students had better talent in computer learning than females, and males could address computer problems and learn computer knowledge better than females. To some extent, males had better logic, practical problem-solving, and computing skills than females (

Saha & Zaman, 2017). These performances can be attributed to the masculine principles of higher education and scientific traditions, strengthening the male status in digital access and usage (

Kuhn et al., 2023). In general, gender influences males’ and females’ computer access and usage.

4.2. Region

Rural students had significantly lower scores than urban students at each level of the digital divide. This is because urban or developed areas have sufficient digital resources at various educational levels, digital infrastructure in the social community, and a rich digital atmosphere in the local business environment. Urban students had more chances to access and use computers in primary and secondary education, as the government of urban areas had sufficient resources to provide digital support, such as digital devices and computer training (

Wang, 2013). In contrast, rural students do not have the same opportunities to learn computer knowledge and access computers in their compulsory education, as rural schools have limited computer education resources and cannot provide students with adequate computer devices and training support (

Li & Ranieri, 2013). In addition,

J. Guo and Chen (

2023) pointed out that educational inequality between urban and rural areas widens the gap in higher education participation between urban and rural students, resulting in rural students not receiving enough digital education from higher education compared to their urban counterparts.

Second, urban areas offer adequate digital devices and practical support in the community living spaces, increasing the digital divide between rural and urban areas. Urban students are immersed in a technological environment daily and are exposed to the updates and iterations of technological information, undoubtedly contributing to their digital knowledge and awareness. Urban students have more opportunities to enjoy the multiple digital technologies applied in their community’s public activities (

Wang, 2013). In contrast, in rural areas, it is hard to provide digital platforms for students to access and use digital devices in their community areas (

Li & Ranieri, 2013), as they do not have sufficient economic support to establish the necessary digital infrastructure.

Third, in urban areas, multiple local companies with advanced digital technologies and innovative digital knowledge enhance the digital awareness and information in their living surroundings, while rural students seldom have the chance to acknowledge digital development and application in practical terms. As

Salemink et al. (

2017) pointed out, urban areas with good digital technology development would provide more opportunities for students to acknowledge digital information in an excellent digital atmosphere. However, rural areas have not developed innovative technologies in their local communities, which could not provide students with the same opportunities to learn and access digital information in their living environment.

4.3. Family SES

Significant differences in the digital divide between high-family SES and low-family SES students are reflected in three dimensions: parents’ educational level, parents’ occupational level, and family annual income. First, parents’ educational level benefits children’s computer usage, as they received basic computer education to support their children’s computer knowledge and practice (

Li & Ranieri, 2013), while low parental educational level can be a barrier to cultivating students’ information and digital skills (

Warih et al., 2020). This can be attributed to people from low-family SES having a lower chance of accessing education and facing various social inequalities, resulting in a disadvantaged starting point compared to those from high-family SES (

Russell-Bennett et al., 2022).

Furthermore, parents’ occupational level is related to their work opportunities in using computers, which would influence their digital knowledge and the support they can provide to their children.

Wattal et al. (

2011) reported that parents’ occupational level would affect their children’s digital access and usage, as various occupational positions have different requirements for the staff’s computer skills. High occupational positions (e.g., white-collar jobs) would require staff with higher computer skills to use computers to address job tasks. In contrast, low occupational positions (e.g., blue-collar jobs) would not require staff to use computers and would not necessitate their computer skills. In this case, parents’ occupational status affects their computer skills and, consequently, their ability to provide digital support to their children in their daily lives.

In addition, family income plays a significant role in influencing students’ digital divide. Students from families with sufficient economic resources would have multiple channels (e.g., computers and tablets) to acquire digital information and knowledge (

Fang & Ng, 2023;

Fang et al., 2024). However, students from low-income families have limited opportunities to access digital technologies in their daily lives, as their families cannot afford the necessary financial support and basic hardware equipment (

Wong et al., 2015).

5. Conclusions

This study revealed significant differences in the digital divide between male and female students, urban and rural students, and high-family SES and low-family SES students. Students’ sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors influence their digital access, capability, and outcomes. Based on the research findings, three suggestions are proposed: 1. Inspired by gender, students should break traditional gender stereotypes and pursue their interests in choosing computer-related majors and learning computer skills. 2. Students living in rural or underdeveloped urban areas are encouraged to access and use computers via their teachers or peers with sufficient digital resources. 3. Students from low-family SES are encouraged to access more digital devices with sufficient digital resources through their peers or relatives. Meanwhile, teachers and parents should stimulate disadvantaged students’ interest in computer access and usage. Additionally, governments and schools should conduct effective measures to meet students’ digital learning needs. This study contributes an updated theoretical framework of the digital divide by adding new factors to the digital access level, including the university computing environment and the living community (local technological companies and public places), as well as the sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors at the three levels. It also suggests practical measures to reduce the digital divide in higher education.

Based on the research findings, we propose the following recommendations for policymakers. First, enhance gender confidence by implementing policies that support female students in computer and science learning. For example, STEAM education can effectively challenge traditional gender stereotypes regarding subject preferences. Second, improve access to digital resources by developing robust initiatives in schools located in rural or underdeveloped areas, ensuring that students can access and utilize high-tech devices. Finally, establish public digital centers to provide students with access to technology, which can help reduce disparities related to family socioeconomic status.

6. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Several limitations of this study can be summarized as follows. First, the limited sampling of the participating university and undergraduate students may only represent part of the digital divide in higher education. To address this limitation, the researcher adopted random sampling to ensure the scope of the targeted participants and narrowed the types of universities in higher education. Future research could include a larger population of participants and more cities (e.g., first-tier cities and second-tier cities) in various countries. Second, future research is recommended to explore the digital divide in the disadvantaged group of students from underdeveloped urban areas or rural areas and low-family SES to help them address difficulties. Third, future research could use the updated theoretical framework and related questionnaires to explore the trend of the digital divide at the higher educational level. Lastly, this study analyzed data from undergraduate students’ self-report questionnaires and interviews, which may carry a risk of biased results. Future research could consider including various types of data sources to enhance the comprehensiveness and objectivity of the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, X.F.; writing—review and editing, H.X., D.T.K.N.; supervision, project administration, H.X.; funding acquisition, D.T.K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department Collaborative Fund from the Education University of Hong Kong [grant number: MIT/DCRF02/25-26].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Commission of the Education University of Hong Kong (Approval code: 2022-2023-0102; approval date: 9 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participating teachers and students.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adhikari, J., Mathrani, A., & Scogings, C. (2017). A longitudinal journey with BYOD classrooms: Issues of access, capability and outcome divides. Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aissaoui, N. (2022). The digital divide: A literature review and some directions for future research in light of COVID-19. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 71(8/9), 686–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Dardet, S. M., Lara, B. L., & Pérez-Padilla, J. (2020). Older adults and ICT adoption: Analysis of the use and attitudes toward computers in elderly Spanish people. Computers in Human Behavior, 110, 106377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A., Jung, I., Xiao, J., Vladimirschi, V., Schuwer, R., Egorov, G., & Lambert, S. (2020). A global outlook to the interruption of education due to COVID-19 pandemic: Navigating in a time of uncertainty and crisis. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 1–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, S., & Eachus, P. (2002). Developing the computer user self-efficacy (CUSE) scale: Investigating the relationship between computer self-efficacy, gender and experience with computers. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 26(2), 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning. Conducting, and Evaluating, 260(1), 375–382. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Choosing a mixed methods design. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2(1), 53–106. [Google Scholar]

- Faloye, S. T., & Ajayi, N. (2022). Understanding the impact of the digital divide on South African students in higher educational institutions. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 14(7), 1734–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X., Gao, L., & Xu, H. (2024). Digital divide in students’ online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of Hong Kong. In H. Xu (Ed.), Curriculum innovation in East Asian schools: Contexts, innovations and impact. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X., & Ng, D. T. K. (2023). Educational inequity in prolonged online learning among young learners: A two-year longitudinal study of Chinese cross-border education. Education and Information Technologies, 29(10), 11955–11977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Betancor, S. M., López-Puig, A. J., & Cardenal, M. E. (2021). Digital inequality at home. The school as compensatory agent. Computers & Education, 168, 104195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C., & Wan, B. (2022). The digital divide in online learning in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Technology in Society, 71, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., & Chen, J. (2023). Can China’s higher education expansion reduce the educational inequality between urban and rural areas? The Journal of Higher Education, 94(5), 638–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C., & Lawton, W. (2018). Universities, the digital divide and global inequality. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 40(6), 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, A., Schneider, U., & Schwabe, A. (2023). Digital reading and gender inequality in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 42(1), 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembani, R., Gunter, A., Breines, M., & Dalu, M. T. B. (2020). The same course, different access: The digital divide between urban and rural distance education students in South Africa. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 44(1), 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Ranieri, M. (2013). Educational and social correlates of the digital divide for rural and urban children: A study on primary school students in a provincial city of China. Computers & Education, 60(1), 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythreatis, S., Singh, S. K., & El-Kassar, A.-N. (2021). The digital divide: A review and future research agenda. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 175, 121359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathrani, A., Sarvesh, T., & Umer, R. (2022). Digital divide framework: Online learning in developing countries during the COVID-19 lockdown. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 20(5), 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2018). Bridging the digital gender divide include, upskill, innovate. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/going-digital/bridging-the-digital-gender-divide.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- OECD. (2021). Bridging digital divides in G20 countries—OECD report for the G20 infrastructure working group. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/digital/bridging-digital-divides-in-g20-countries-35c1d850-en.htm (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- OECD. (2023). Expand existing support and address the gender digital divide. In Digital skills for private sector competitiveness in Uzbekistan. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resch, K., Alnahdi, G., & Schwab, S. (2023). Exploring the effects of the COVID-19 emergency remote education on students’ social and academic integration in higher education in Austria. Higher Education Research & Development, 42(1), 215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Russell-Bennett, R., Raciti, M., Letheren, K., & Drennan, J. (2022). Empowering low-socioeconomic status parents to support their children in participating in tertiary education: Co-created digital resources for diverse parent personas. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(2), 527–545. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, S. R., & Zaman, M. O. (2017). Gender digital divide in higher education: A study on university of Barisal, Bangladesh. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 22(1), 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemink, K., Strijker, D., & Bosworth, G. (2017). Rural development in the digital age: A systematic literature review on unequal ICT availability, adoption, and use in rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies, 54, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerder, A., Van Deursen, A., & Van Dijk, J. (2017). Determinants of Internet skills, uses and outcomes. A systematic review of the second-and third-level digital divide. Telematics and Informatics, 34(8), 1607–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholkmann, A., Olsen, D. S., & Wollscheid, S. (2024). Perspectives on disruptive change in higher education. A critical review of digital transformation during COVID-19. Higher Education Research & Development, 43, 1355–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z., Wang, C., & Bergmann, L. (2020). China’s prefectural digital divide: Spatial analysis and multivariate determinants of ICT diffusion. International Journal of Information Management, 52, 102072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, K. A., Kale, U., Curtis, R., Akcaoglu, M., & Bernstein, M. (2020). Digital divide among higher education faculty. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y. M., Chen, P. C., Law, K. M., Wu, C. H., Lau, Y. Y., Guan, J., He, D., & Ho, G. T. (2021). Comparative analysis of Student’s live online learning readiness during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in the higher education sector. Computers & Education, 168, 104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deursen, A., & Van Dijk, J. (2011). Internet skills and the digital divide. New Media & Society, 13(6), 893–911. [Google Scholar]

- Van Deursen, A. J., Helsper, E., Eynon, R., & Van Dijk, J. A. (2017). The compoundness and sequentiality of digital inequality. International Journal of Communication, 11, 452–473. [Google Scholar]

- Van Deursen, A. J., & Helsper, E. J. (2015). The third-level digital divide: Who benefits most from being online? In Communication and information technologies annual (Vol. 10, pp. 29–52). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, J. (2020). The digital divide. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, J. A. (2005). The deepening divide: Inequality in the information society. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2017). Digital divide: Impact of access. The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilakopoulou, P., & Hustad, E. (2023). Bridging digital divides: A literature review and research agenda for information systems research. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(3), 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P. Y. (2013). Examining the digital divide between rural and urban schools: Technology availability, teachers’ integration level and students’ perception. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 2(2), 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warih, M. P., Rindarjono, M. G., & Nurhadi, N. (2020,The impact of parental education levels on digital skills of students in urban sprawl impacted areas. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1469(1), 012071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, M. W., & Pacheco, M. (2000). Interobserver agreement in behavioral research: Importance and calculation. Journal of Behavioral Education, 10(4), 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattal, S., Hong, Y., Mandviwalla, M., & Jain, A. (2011, January 4–7). Technology diffusion in the society: Analyzing digital divide in the context of social class. 2011 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, K. K., Teo, H. H., Chan, H. C., & Tan, B. C. (2011). Conceptualizing and testing a social cognitive model of the digital divide. Information Systems Research, 22(1), 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y. C., Ho, K. M., Chen, H., Gu, D., & Zeng, Q. (2015). Digital divide challenges of children in low-income families: The case of Shanghai. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 33(1), 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. (2019). Digital transformation in higher education: Critiquing the five-year development plans (2016–2020) of 75 Chinese universities. Distance Education, 40(4), 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. (2020). China’s higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: Some preliminary observations. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(7), 1317–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., Lu, Y., Huang, W., & Wang, Q. (2010). Internet inequality: The relationship between high school students’ Internet use in different locations and their Internet self-efficacy. Computers & Education, 55(4), 1405–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Llorente, A. M. P., & Gómez, M. C. S. (2021). Digital competence in higher education research: A systematic literature review. Computers & Education, 168, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).