Embedding Math Problems in Cultural City Tours to Increase Student Engagement and Inclusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Pedagogical Tours Around Cities

- 1.

- Selection of the city, monuments, and route and historical research:

- A city is chosen as the focus of a pedagogical tour, along with key monuments and landmarks that will be included in the route.

- Historical research is conducted to identify significant events, cultural influences, and noteworthy historical facts related to the selected locations.

- This research serves as the foundation for the content, ensuring accuracy and depth in the storytelling approach.

- 2.

- Definition of the storyline, inclusive elements, and gaming characteristics:

- A storyline is developed to guide users through the historical and mathematical exploration of the city.

- Inclusive elements are incorporated to ensure accessibility for diverse audiences, considering cultural representation, language inclusivity, and varying learning needs.

- Gamification features are designed to enhance engagement, including interactive challenges, problem-solving activities, and digital rewards.

- 3.

- Content development using specified templates in Canva:

- The researched content is structured using predefined templates in Canva, ensuring consistency in design and presentation.

- Visual and textual elements, including images, infographics, and interactive materials, are integrated to make the experience more immersive.

- The templates also facilitate easy adaptation for different formats and languages.

- 4.

- Development of solutions to the problems:

- Based on the content, analytical solutions are created to enhance the user experience.

- 5.

- Finalization and publication of outputs in different forms

- The final versions of the materials are published in different formats and print-friendly versions.

- Dissemination strategies are implemented to ensure broad accessibility, allowing educators, students, and the public to benefit from the project.

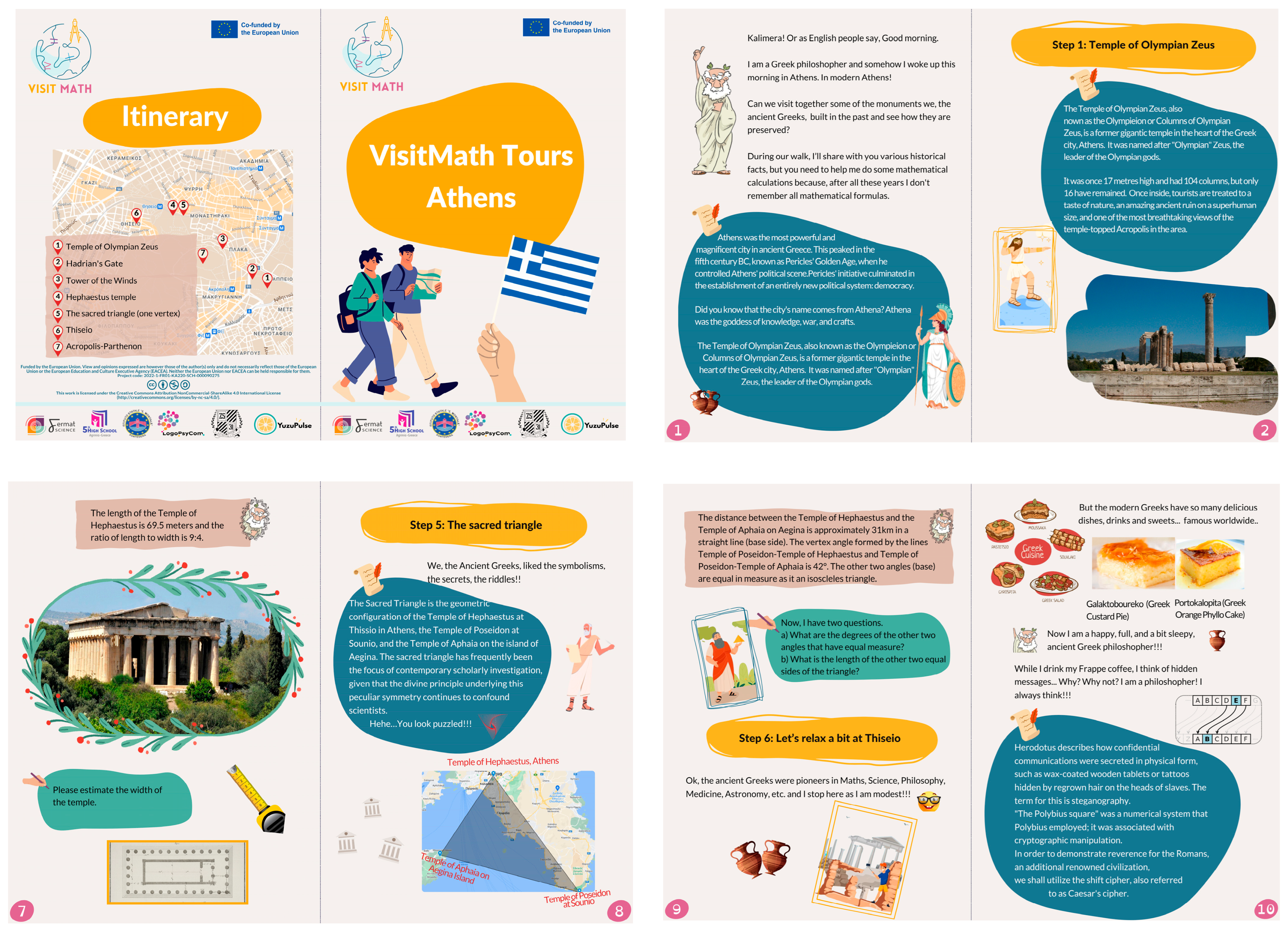

An Example of a Pedagogical Tour: The Case of Athens

- 1.

- Historical and cultural insights:

- Participants visit significant Athenian landmarks such as the Temple of Olympian Zeus, Hadrian’s Gate, the Tower of the Winds, the Temple of Hephaestus, and the Acropolis-Parthenon.

- Each stop provides historical context, highlighting the city’s evolution from ancient Greece to the Roman era and its impact on philosophy, democracy, and science.

- 2.

- Mathematical challenges and problem-solving

- The tour integrates mathematical problems linked to each site, encouraging participants to calculate proportions, areas, volumes, and geometric relationships.

- Examples include scaling a miniature temple, computing the perimeter of a semicircle, estimating an octagonal tower’s volume, and solving an isosceles triangle’s dimensions based on historical locations.

- 3.

- Gamification and interactivity

- The experience is interactive, requiring participants to assist the philosopher in solving mathematical puzzles.

- Gamification elements include encryption challenges (e.g., Caesar’s Cipher), secret messages, and real-world applications of steganography.

- 4.

- Reflection and final challenge

- The journey ends at the Acropolis and the Parthenon, where participants reflect on the mathematical and cultural contributions of ancient Greece.

- A final encrypted message invites them to decode the most significant Greek contribution to humanity using a shift cipher.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Aims and Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

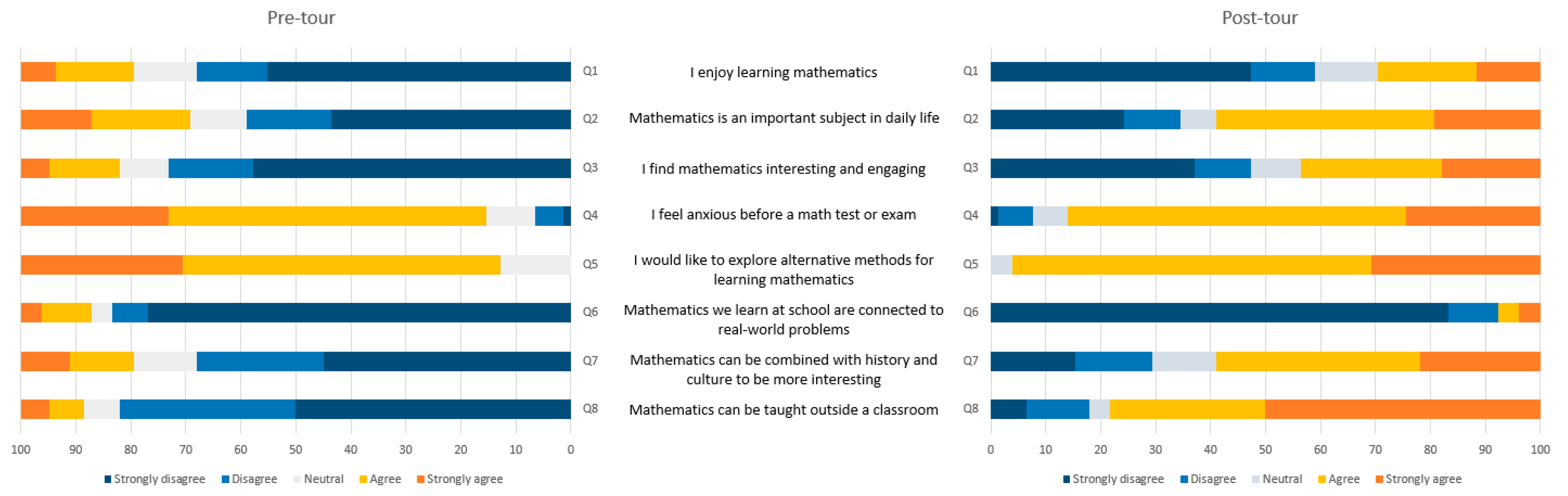

4.1. Pre- and Post-Tour Common Questions

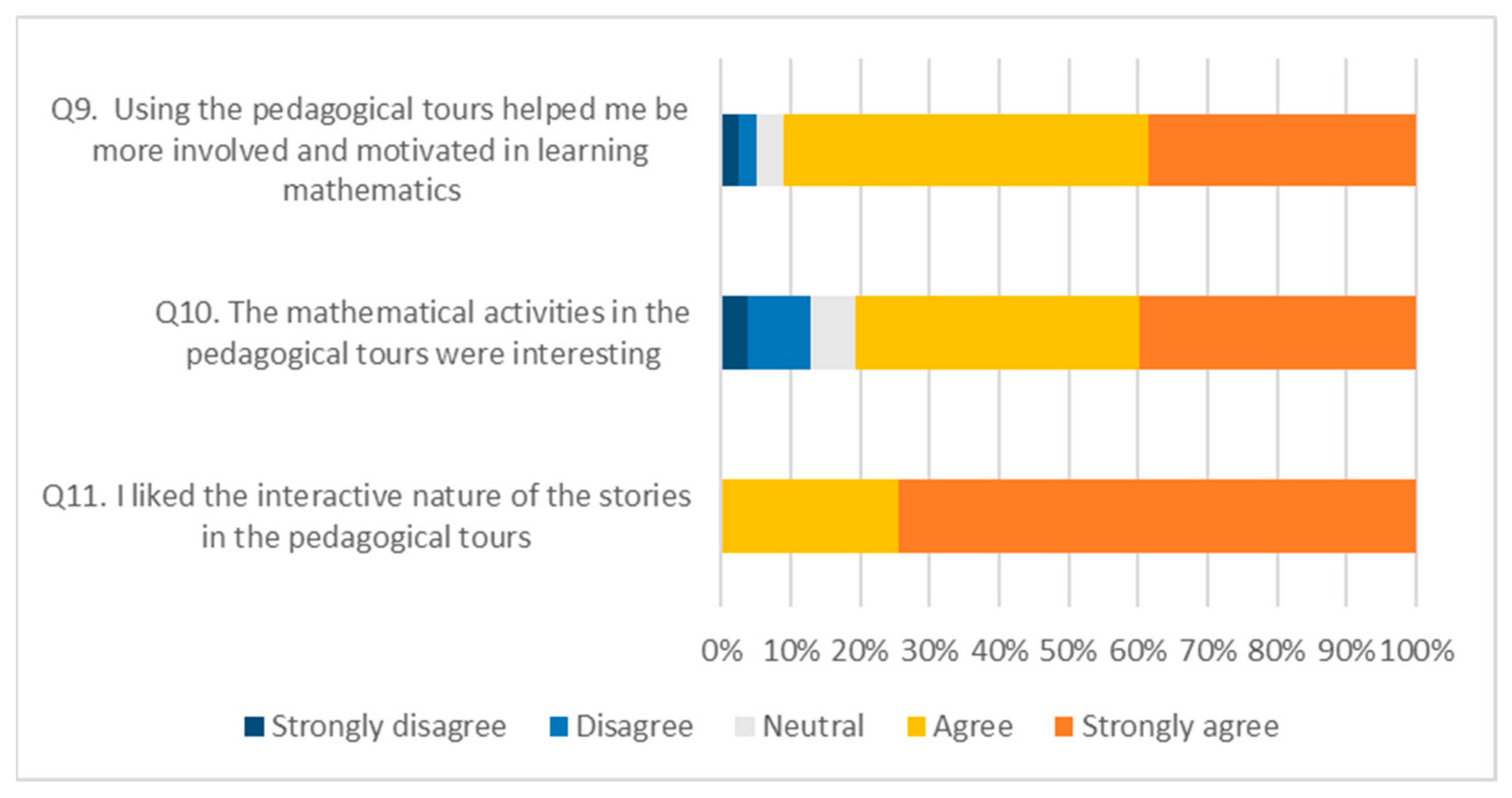

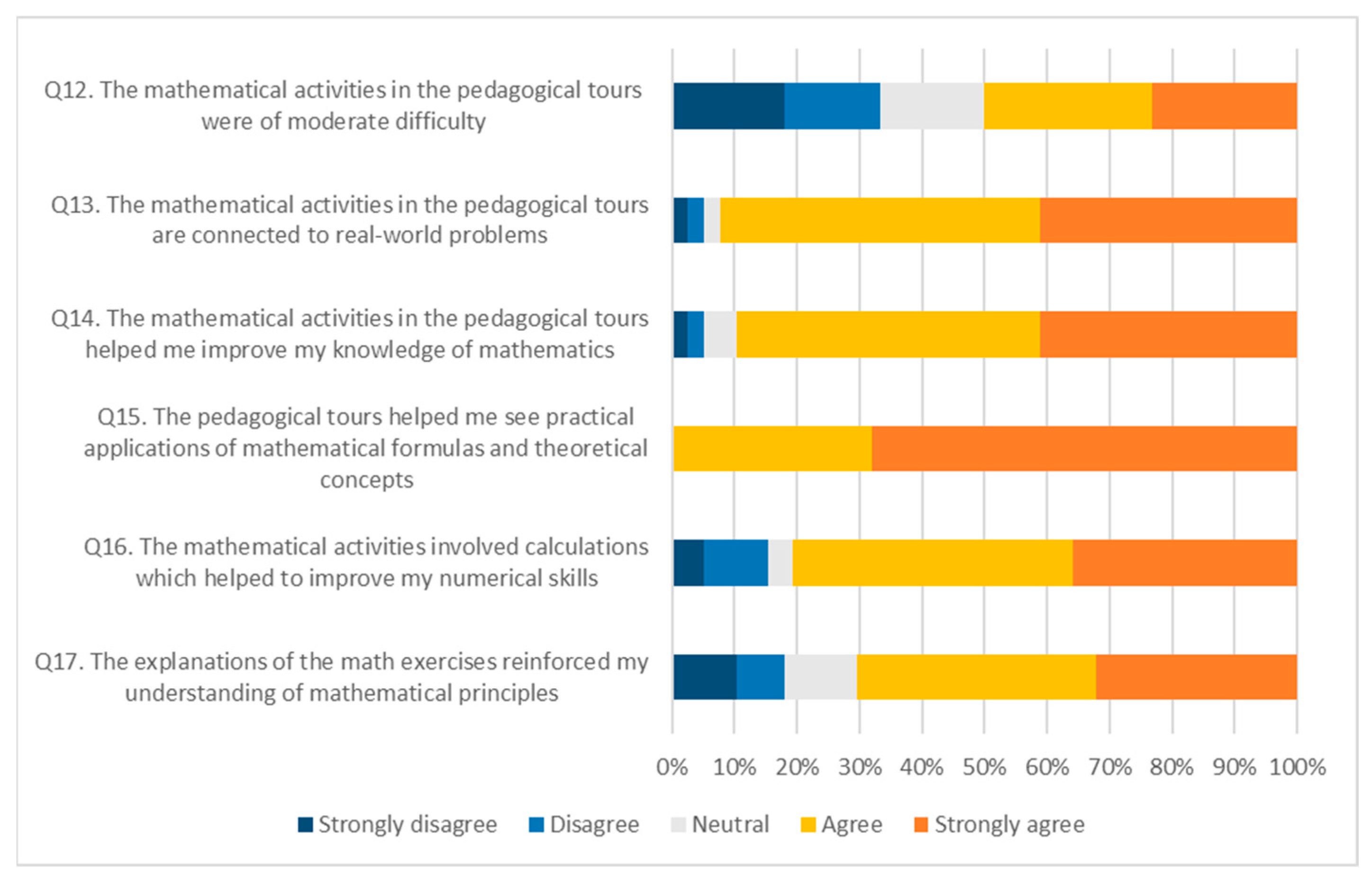

4.2. Post-Tour Questions

4.3. Teachers’ Interviews

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question | Strongly Disagree | Strongly Agree | |||

| Q1. I enjoy learning mathematics | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q2. Mathematics is an important subject in daily life | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q3. I find mathematics interesting and engaging | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q4. I feel anxious before a math test or exam | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q5. I would like to explore alternative methods for learning mathematics | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q6. The mathematics we learn at school are connected to real-world problems | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q7. Mathematics can be combined with history and culture to be more interesting | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q8. Mathematics can be taught outside a classroom | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Appendix B

| Question | Strongly Disagree | Strongly Agree | |||

| Q1. I enjoy learning mathematics | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q2. Mathematics is an important subject in daily life | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q3. I find mathematics interesting and engaging | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q4. I feel anxious before a math test or exam | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q5. I would like to explore alternative methods for learning mathematics | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q6. The mathematics we learn at school are connected to real-world problems | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q7. Mathematics can be combined with history and culture to be more interesting | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q8. Mathematics can be taught outside a classroom | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q9. Using the pedagogical tours helped me be more involved and motivated in learning mathematics | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q10. The mathematical activities in the pedagogical tours were interesting | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q11. I liked the interactive nature of the stories in the pedagogical tours | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q12. The mathematical activities in the pedagogical tours were of moderate difficulty | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q13. The mathematical activities in the pedagogical tours are connected to real-world problems | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q14. The mathematical activities in the pedagogical tours helped me improve my knowledge of mathematics | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q15. The pedagogical tours helped me see practical applications of mathematical formulas and theoretical concepts | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q16. The mathematical activities involved calculations which helped to improve my numerical skills | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q17. The explanations of the mathematical activities reinforced my understanding of mathematical principles | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

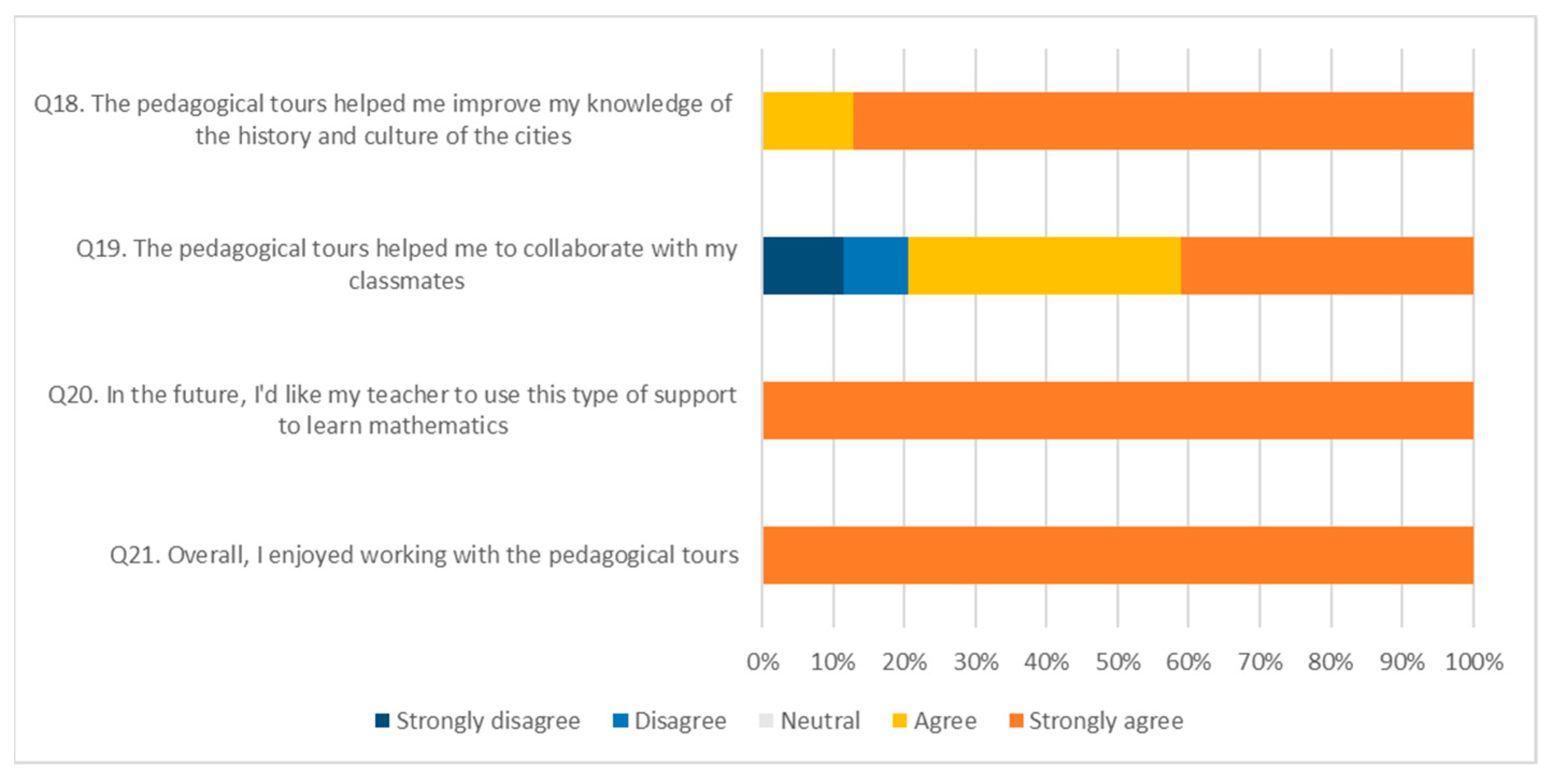

| Q18. The pedagogical tours helped me improve my knowledge of the history and culture of the cities | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q19. The pedagogical tours helped me to collaborate with my classmates | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q20. In the future, I’d like my teacher to use this type of support to learn mathematics | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Q21. Overall, I enjoyed working with the pedagogical tours | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Appendix C. Student Questionnaire Items—Research Questions

| Research Question | Focus Area | Related Questionnaire Items |

| RQ1. Does the specific approach to learning mathematics increase students’ engagement? | Motivation, enjoyment, interest, and student attitudes toward learning mathematics | Q1, Q3, Q5, Q9, Q10, Q11, Q20, Q21 |

| RQ2. Do the math activities in the tours help students to improve their math knowledge and skills? | Mathematical understanding, skills, problem-solving, and application | Q13, Q14, Q15, Q16, Q17 |

| RQ3. Are the pedagogical tours suitable for students with different abilities? | Accessibility, difficulty level, inclusivity, and collaboration | Q12, Q19 |

| RQ4. Do students retain mathematical concepts better when they are taught through an experiential learning activity such as the pedagogical tours with embedded math activities? | Experiential learning, contextualization, and long-term understanding | Q2, Q6, Q7, Q8, Q18 |

References

- Almulla, M. A. (2020). The effectiveness of the project-based learning (PBL) approach as a way to engage students in learning. SAGE Open, 10(3), 2158244020938702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, D. (2023). Assessing the benefits of gamification in mathematics for student gameful experience and gaming motivation. Computers & Education, 200, 104806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, D., Vasconcelos, L., & Orey, M. (2017). Motivation and learning engagement through playing math video games. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 14(2), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belbase, S., Mainali, B. R., Kasemsukpipat, W., Tairab, H., Gochoo, M., & Jarrah, A. (2022). At the dawn of science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM) education: Prospects, priorities, processes, and problems. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 53(11), 2919–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaler, J. (2016). Mathematical mindsets: Unleashing students’ potential through creative math, inspiring messages, and innovative teaching. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- English, L. D. (2016). STEM education K-12: Perspectives on integration. International Journal of STEM Education, 3(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Oliveras, A., Espigares-Gámez, M. J., & Oliveras, M. L. (2021). Implementation of a playful microproject based on traditional games for working on mathematical and scientific content. Education Sciences, 11(10), 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellín, C. J., Calles-Esteban, F., Valledor, A., Gómez, J., Otón-Tortosa, S., & Tayebi, A. (2023). Enhancing student motivation and engagement through a gamified learning environment. Sustainability, 15(19), 14119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J., Miller, J., Choy, B. H., & Hunter, R. (2020). Innovative and powerful pedagogical practices in mathematics education (pp. 293–318). Research in Mathematics Education in Australasia 2016–2019. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Indriayu, M. (2019). Effectiveness of experiential learning-based teaching material in mathematics. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 8(1), 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Irmayanti, M., & Chou, L. F. (2025). Storytelling and math anxiety: A review of storytelling methods in mathematics learning in Asian countries. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 40(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, H. N. (2014). History in mathematics education: A hermeneutic approach. In Mathematics & mathematics education: Searching for common ground (pp. 75–88). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabuye Batiibwe, M. S. (2024). The role of ethnomathematics in mathematics education: A literature review. Asian Journal for Mathematics Education, 3(4), 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalelioğlu, F. (2015). A new way of teaching programming skills to K-12 students: Code. org. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, E., Hodge-Zickerman, A., York, C. S., Smith, T. J., & Mayall, H. (2023). Examining the effect of inquiry-based learning versus traditional lecture-based learning on students’ achievement in college algebra. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education, 18(1), em0724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laato, S., Lindberg, R., Laine, T. H., Bui, P., Brezovszky, B., Koivunen, L., De Troyer, O., & Lehtinen, E. (2020, June 15–17). Evaluation of the pedagogical quality of mobile math games in app marketplaces. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC) (pp. 1–8), Cardiff, UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarinis, F., Alexandri, K., Panagiotakopoulos, C., & Verykios, V. S. (2020). Sensitizing young children on internet addiction and online safety risks through storytelling in a mobile application. Education and Information Technologies, 25, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarinis, F., & Konstantinidou, S. (2025). Learning about children’s rights through engaging visual stories promoting in-class dialogue. European Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Education, 6(2), e02504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., Capraro, R. M., & Bicer, A. (2019). Affective mathematics engagement: A comparison of STEM PBL versus non-STEM PBL instruction. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 19, 270–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, C., Ay, Z. S., & Güler, G. (2021). The effectiveness of inquiry-based learning on middle school students’ mathematics reasoning skill. Athens Journal of Education, 8(4), 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujatha, S., & Vinayakan, K. (2023). Integrating math and real-world applications: A review of practical approaches to teaching. International Journal of Computational Research and Development, 8(2), 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, L., Green, M., Goldsby, D., & Parker, D. (2018). Digital storytelling as a problem-solving strategy in mathematics teacher education: How making a math-eo engages and excites 21st-century students. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science, 2(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, A. E., Basile, C. G., & Albright, L. (2011). The effect of an experiential learning program on middle school students’ motivation toward mathematics and science. RMLE Online, 35(3), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, J. M. (2006). Computational thinking. Communications of the ACM, 49(3), 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazkis, R., & Liljedahl, P. (2019). Teaching mathematics as storytelling. Brill. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lazarinis, F. Embedding Math Problems in Cultural City Tours to Increase Student Engagement and Inclusion. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121683

Lazarinis F. Embedding Math Problems in Cultural City Tours to Increase Student Engagement and Inclusion. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121683

Chicago/Turabian StyleLazarinis, Fotis. 2025. "Embedding Math Problems in Cultural City Tours to Increase Student Engagement and Inclusion" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121683

APA StyleLazarinis, F. (2025). Embedding Math Problems in Cultural City Tours to Increase Student Engagement and Inclusion. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121683