Addressing the Challenges of STEM Mature-Aged Students: Faculty Role in Promoting Sustainability and Well-Being in Higher Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Review the challenges and needs of mature-aged STEM students in the context of their well-being;

- (2)

- Review the role of faculty in supporting the well-being of mature-aged STEM students to promote sustainability;

- (3)

- Analyse the results of the survey on various well-being dimensions of mature-aged STEM students from the perspective of how the faculty can support the students;

- (4)

- Provide recommendations to the faculty on how to support the well-being of mature-aged STEM students to promote sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

- (1)

- Time Frame: The specific time frame for the inclusion of the documents was restricted to the period from 2019 to 2025 to best capture recent developments;

- (2)

- Topic Relevancy: The documents selected addressed directly the issue of well-being of mature-aged STEM students, and the role of the faculty in supporting their well-being in a holistic manner;

- (3)

- Quality of Sources: Preference was given to the peer-reviewed articles from high-impact journals and conference proceedings indexed in Web of Science and Scopus;

- (4)

- Geographical Context: In the analysis, studies were included from diverse regions to provide a global perspective (no exclusion criteria);

- (5)

- Methodological Rigor: The selection of the documents was based on the methodological soundness of the research design, namely case studies, empirical studies, and theoretical frameworks.

- (1)

- Selection Criteria: For the survey, RTU mature-aged STEM students, aged 30+ years, were identified. In total, 1228 students fell within this category.

- (2)

- Sample Size Justification: While the recommended sample size for a 95% confidence level and ±5% margin of error was 293 respondents by Cochran’s formula (Nanjundeswaraswamy & Divakar, 2021), this study surveyed 119 mature-aged STEM students at RTU, representing approximately 10% of the total target population, where N = 1228. This sample size yields a margin of error of approximately ±8.5%, which is acceptable for exploratory research and allows for meaningful insights into trends and perceptions within this specific student group (Conroy, 2021). Additionally, the sample provides sufficient variability to identify key patterns across well-being dimensions relevant to the research objectives.

- (3)

- Procedures: The survey was conducted via questionnaire sent through the RTU IT Department from 20 April to 25 May 2025. The response rate was 10%.

- (1)

- Selection Criteria: Students who participated in the survey and indicated a willingness to share their experience on various well-being dimensions were selected. In total, 24 students identified their willingness to participate in the semi-structured interviews.

- (2)

- Sample Size Justification: Of the 24 students who expressed a willingness to participate in follow-up interviews, a purposive sample of 6 were selected to ensure diversity in terms of gender, study level (Bachelor/Master), and study mode (full-time/part-time), with the goal of capturing a broad range of perspectives on well-being dimensions. This approach aligns with established qualitative research practices, where smaller, purposeful selected samples are considered appropriate for exploratory studies focused on depth rather than generalisation (Patton, 2015). Moreover, qualitative research literature suggests that studies aiming to identify core themes can achieve sufficient data saturation with as few as 6 to 12 interviews, depending on the study focus and participant homogeneity (Guest et al., 2006). Given the specific target group of mature-aged STEM students and the exploratory nature of this study, 6 interviews were considered adequate to provide meaningful insights while maintaining a manageable depth of analysis. Nonetheless, future research could benefit from expanding the number of interviewees to further enrich the data and increase representativeness across different profiles of mature-aged students.

- (3)

- Procedures: The invitation to participation in the interview was sent via email to the selected participants. Before the interview, the interviewees signed the informed consent to participate in a semi-structured interview. The interviews were conducted online using MS Teams and had a duration of up to 1 h. After the interview, the minutes were prepared and harmonised with the interviewees.

2.2. Literature Review

2.2.1. Challenges and Unique Needs of Mature-Aged Students

Academic Well-Being

Financial Well-Being

Physical Well-Being

Psychological Resilience Well-Being

Relational Well-Being

2.3. The Role of Faculty in Supporting the Well-Being of Mature-Aged Students

2.3.1. Faculty as a Person with a Personality: Relational Well-Being

2.3.2. Study Content: Academic Well-Being, Psychological Well-Being

2.3.3. Additional Networking and Experience: Relational Well-Being, Financial Well-Being, Academic Well-Being

2.3.4. Inclusion in the Study Environment: Relational Well-Being, Psychological Well-Being

2.4. Relation Between Sustainability and Well-Being of Mature-Aged Students

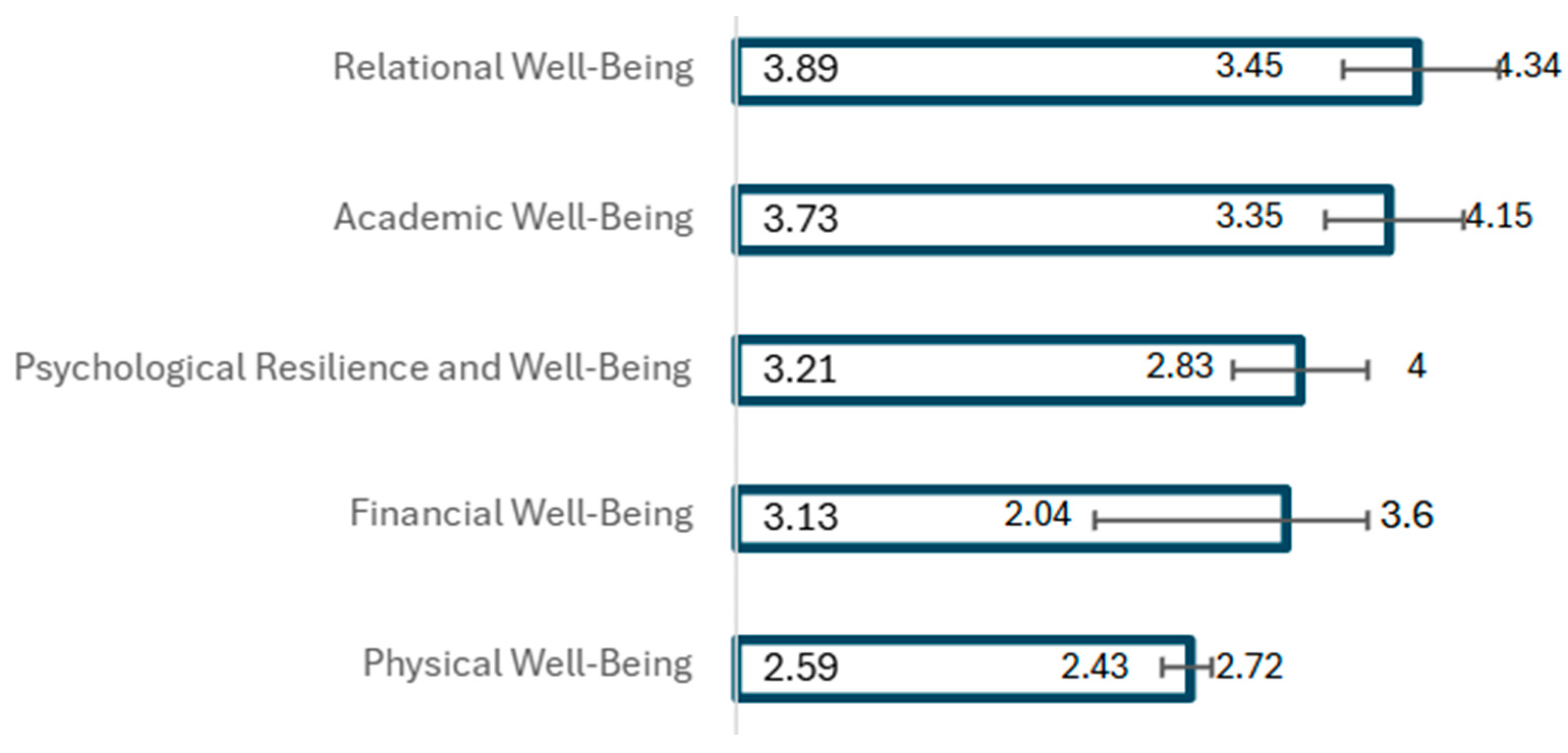

3. Results

“The teachers were divided into two groups—teachers with experience, who understand, are able to assess whether the student is an adult student or a young person. The second group of teachers, who themselves feel insecure, take their first steps. (…). And unfortunately, I am the evil one who will point it out and notice that stumble, then there is (conflict). The teacher understands his mistake, but does not want to admit it and personal resentment begins, which then led to unequal treatment.”(here and henceforth translation of respondents’ quotes from Latvian)

“It is very pleasant for the teaching staff if there is a student who is interested, and then (…) good relationships naturally developed. (…) A mature person has a different kind of attitude towards a person (instructor), which maybe young people don’t have, because young people always feel like what is she telling me there, what will I do with it, why do I need it?”

“I really feel the age difference. For the first two years we had a joint (WhatsApp, version 2.22.13.77) group, but now they have separate groups, because I guess it feels more like I am their mother’s age.”

“I have a normal relationship with my lecturers, but especially with the lecturers at the Banking University, because I am more similar to them in terms of age.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aarntzen, L., Nieuwenhuis, M., Endedijk, M. D., van Veelen, R., & Kelders, S. M. (2023). STEM students’ academic well-being at university before and during later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional cohort and longitudinal study. Sustainability, 15, 14267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAli, R., Alsoud, K., & Athamneh, F. (2023). Towards a sustainable future: Evaluating the ability of STEM-based teaching in achieving sustainable development goals in learning. Sustainability, 15(16), 12542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C., Fernandes, J. L., & Almeida, L. S. (2024). Mature working student parents navigating multiple roles: A qualitative analysis. Education Sciences, 14(7), 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, L., Robinson, K., Dare, J., & Costello, L. (2021). Widening the lens on capital: Conceptualising the university experiences of non-traditional women nurse students. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(7), 1359–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacovic, M., Andrijasevic, Z., & Pejovic, B. (2022). STEM education and growth in Europe. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 13(3), 2348–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglow, L., & Gair, S. (2019). Mature-aged social work students: Challenges, study realities, and experiences of poverty. Australian Social Work, 72(1), 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, M., & Ehlers, U.-D. (2022, June 20–22). Building an inclusive academic environment: Challenges and needs of non-traditional students and potentials to address them. Annual Conference of European Distance and E-Learning Network (pp. 158–166), Tallinn, Estonia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, L. A., Fabris, M. A., & Oraison, H. (2024). How personal and familial narratives affect the decision making of mature-aged first-in-family students pursuing university. Adult Education Quarterly, 74(2), 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, R. M. (2021). The RCSI sample size handbook. Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. Available online: https://www.beaumontethics.ie/docs/application/samplesize2021.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Crank, R., & Spence, J. (2024). Self-reported online science learning strategies of non-traditional students studying a university preparation science course. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 30(2), 483–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, N., & Emery, S. (2021). “Shining a Light” on mature-aged students in, and from, regional and remote Australia. Student Success, 12(2), 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, N. L., Emery, S. G., Allen, P., & Baird, A. (2022). I probably have a closer relationship with my internet provider: Experiences of belonging (or not) among mature-aged regional and remote university students. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 19(4), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahs, A., Berzins, A., & Krumins, J. (2021, May 11–14). Challenges of depopulation in Latvia’s rural areas. 2021 International Conference Economic Science for Rural Development (Vol. 11, pp. 535–545), Jelgava, Latvia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dare, E. A., Keratithamkul, K., Hiwatig, B. M., & Li, F. (2021). Beyond content: The role of STEM disciplines, real-world problems, 21st century skills, and STEM careers within science teachers’ conceptions of integrated STEM education. Education Sciences, 11(11), 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehtjare, J., & Uzule, K. (2023). Sustainable higher education management: Career drivers of academic staff. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 25(2), 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervis, O.-A., Trifan, E., & Jitaru, G. (2022). The socio-economic challenges in access to Romanian higher education: Student perception and funding policy directions. In Higher education in Romania: Overcoming challenges and embracing opportunities. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2025, March 5). Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the European council, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions: The union of skills (COM (2025) 90 final). Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d9d9adad-c71b-11ee95d9-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Fischer, S., & Kilpatrick, S. (2023). Review of support provided by student support services. In D. Kember, R. A. Ellis, S. Fan, & A. Trimble (Eds.), Adapting to online and blended learning in higher education. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girmay, M., & Singh, G. K. (2019). Social isolation, loneliness, and mental and emotional well-being among international students in the United States. International Journal of Translational Medical Research and Public Health, 3(2), 1−8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A. E. (2024). Post-traditional students’ perceptions of mattering: The role of faculty and student interaction. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 72(1), 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, A. F. M., & Nielsen, K. B. (2023). Not quite the ideal student: Mature students’ experiences of higher education. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 32(1), 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, P. T. T., Samsudin, M. A., Huy, N. H. D., Tri, N. Q., & An, N. N. (2023). Exploring the influences of teacher professional identity on teachers’ emotion among Vietnamese secondary school teachers. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 25(2), 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrocks, P. T., & Hall, N. C. (2024). Social support and motivation in STEM degree students: Gender differences in relations with burnout and academic success. Interdisciplinary Education and Psychology, 4(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerez, E. (2024). Exploring the contribution of student engagement factors to mature-aged students’ persistence and academic achievement during the first year of university. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 72(3), 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J., & McConnell, C. (2023). Changing mindsets and becoming gritty: Mature students’ learning experiences in a UK university and beyond. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 60(6), 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuga, S., Ayres, P., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2003). The expertise reversal effect. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, P., Duggal, H. K., Lim, W. M., Thomas, A., & Shiva, A. (2024). Student well-being in higher education: Scale development and validation with implications for management education. The International Journal of Management Education, 22(1), 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latvijas Vēstnesis. (2021). Education development guidelines 2021–2027. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/324332-par-izglitibas-attistibas-pamatnostadnem-2021-2027-gadam (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Lengyel, A., Kovács, S., Müller, A., Dávid, L., Szőke, S., & Bácsné Bába, É. (2019). Sustainability and subjective well-being: How students weigh dimensions. Sustainability, 11(23), 6627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-C. (2025). STEM education and sustainability: What role can mathematics education play in the era of climate change? Research in Mathematics Education, 27, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, I. W., & Jackson, D. (2024). Influence of entry pathway and equity group status on retention and the student experience in higher education. Higher Education, 87(5), 1411–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H., Nguyen, A., & Dang, C. T. (2025). Aligning support with the needs of mature students in russell group universities: A systematic literature review. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 73, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, K. (2018). A review of the literature: The needs of nontraditional students in postsecondary education. Strategic Enrollment Management Quarterly, 5(3), 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansson, D. H., & Myers, S. A. (2012). Using mentoring enactment theory to explore the doctoral student–advisor mentoring relationship. Communication Education, 61(4), 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Manzano, L. A., Sirkis, G., Rojas, J. C., Gallardo, K., Vázquez-Villegas, P., Camacho-Zuñiga, C., Membrillo-Hernández, J., & Caratozzolo, P. (2022). Embracing thinking diversity in higher education to achieve a lifelong learning culture. Education Sciences, 12(12), 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mier, C. (2018). Adventures in advising: Strategies, solutions, and situations to student problems in the criminology and criminal justice field. International Journal of Progressive Education, 14(3), 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouton, D., Hartmann, F. G., & Ertl, B. (2023). Career profiles of university students: How STEM students distinguish regarding interests, prestige and sextype. Education Sciences, 13(3), 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G., Walmsley, A., Mir, M., & Osman, S. (2024). The impact of mentoring in higher education on student career development: A systematic review and research agenda. Studies in Higher Education, 50(4), 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjundeswaraswamy, T. S., & Divakar, S. (2021). Determination of sample size and sampling methods in applied research. Proceedings on Engineering Sciences, 3(1), 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R., Baik, C., & Arkoudis, S. (2018). Identifying attrition risk based on the first-year experience. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(2), 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., & Chou, R. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, 372:n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Petkevičiūtė, N., Balčiūnaitienė, A., Ābele, L., & Adamonienė, R. (2024). Students’ emotional intelligence and their attitudes towards creativity interferences: Lithuanian and Latvian case. Proceedings of the Latvia University of Agriculture: Landscape Architecture & Art, 24(24), 105. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, D. H. (2021). The professional development of academic staff in higher education institution. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 23(1), 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasis, R., Paidi, Suhartini, Kuswanto, H., & Hartanti, R. D. (2023). The effect of environmental education open inquiry learning kits on the environmental literacy of pre-service biology teachers. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 25(1), 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, G. D., & Buchwald, F. (2011). The expertise reversal effect: Cognitive load and motivational explanations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 17(1), 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeima of the Republic of Latvia. (2010). Sustainable development strategy for Latvia until 2030. Available online: https://www.mk.gov.lv/lv/media/15132/download?attachment (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Salīte, I., Briede, L., Ivanova, O., Świtała, E., & Boče, A. (2024). An evolutionary-ecological perspective in teacher education: A transdisciplinary approach in ecopedagogy. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 26(2), 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapir, P. (2022). The role of student support practitioners in Israeli higher education institutions. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1361410. [Google Scholar]

- Siivonen, P., & Filander, K. (2020). ‘Non-traditional’ and ‘traditional’ students at a regional Finnish university: Demanding customers and school pupils in need of support. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 39(3), 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamou, P., Tsoli, K., & Babalis, T. (2024). The role of counseling for non-traditional students in formal higher education: A scoping review. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1361410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, A., Karunaratne, N., Exintaris, B., James, S., Al-Juhaishi, A., Don, A., Dai, D. W., & Lim, A. (2024). The impact of resilience on academic performance with a focus on mature learners. BMC Medical Education, 24, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayhorn, T. L. (2012). College students’ sense of belonging: A key to educational success for all students. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Templeton, R. (2021). Factors likely to sustain a mature-age student to completion of their doctorate. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 61(1), 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Trenaman, M. M., & Cheong, L. S. (2024). Sustainable contemplative practices in pre-service teacher education for sustainability. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 26(1), 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rhijn, T., Osborne, C., Gores, D., Keresturi, A., Neustifter, R., Muise, A., & Fritz, V. (2023). “You’re a mature student and you’re a tiny, tiny little fish in a big massive pond of students”: A thematic analysis investigating the institutional support needs of partnered mature students in postsecondary study. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veletsianos, G. (2020). Learning online: The student experience. Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, H. C., Allen, D. M., Buffinton, K., Humphrey, D., Malpiede, M., Miller, R. K., & Volin, J. C. (2024). Cultivating long-term well-being through transformative undergraduate education. PNAS Nexus, 3(9), 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcox, P., Winn, S., & Fyvie-Gauld, M. (2005). ‘It was nothing to do with the university, it was just the people’: The role of social support in the first-year experience of higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 30(6), 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeide, I., & Kalvāne, G. (2023). Mature-age student’s opportunities as a matter of social inclusion in the higher education. In L. Daniela (Ed.), Human, technologies and quality of education, 2023. Proceedings of scientific papers = Cilvēks, tehnoloģijas un izglītības kvalitāte, 2023. Rakstu krājums (796p). University of Latvia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Respondent Number | Gender | Age | Study Level (Bachelor, Master) | Previous Experience | Occupation (Full Time, Part-Time, Unemployed, Self-Employed) | Funding (Public, Private) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 41 | Bachelor | Yes | Unemployed | Public |

| 2 | Female | 42 | Bachelor | Yes | Unemployed | Private |

| 3 | Male | 45 | Bachelor | Yes | Full-time | Public |

| 4 | Female | 35 | Master | Yes | Full-time | Public |

| 5 | Male | 33 | Master | Yes | Part-time | Private |

| 6 | Male | 43 | Bachelor | Yes | Self-employed | Public |

| Phase | Research Method | Description | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | State-of-the-art review | Definition of the aim and objectives of scientific literature review | To review the scientific articles on the concepts of mature-aged students, well-being and sustainability |

| Phase 2 | Criteria for selection and exclusion of sources for the scientific literature review | Unique articles that are indexed in Scopus and Web of Science; used keywords: “mature-aged students,” “higher education,” “STEM,” “well-being,” and “sustainability” | |

| Phase 3 | Grouping and analysis of information obtained by the scientific literature review | Analysis and interpretation of findings. Definition of well-being dimensions | |

| Phase 4 | Survey Research | Definition of criteria for selection of participants for the survey | RTU mature-aged STEM students (aged 30+ years) |

| Phase 5 | Preparation of questions for the survey in taking limitation account the overall aim of the research | Likert scale questions considering five well-being dimensions: academic well-being, financial well-being, physical well-being, psychological resilience and well-being and relational well-being | |

| Phase 6 | Quantitative analysis of the results of the survey | Analysis and interpretation of findings | |

| Phase 7 | Semi-structured interviews | Definition of criteria for selection of participants for the semi-structured interviews | RTU mature-aged STEM students (aged 30+ years) Who participated in the survey and expressed their willingness to participate in the interview. A purposive sample of 6 was selected to ensure diversity in gender, study level (Bachelor/Master), and study mode (full-time/part-time), aiming to capture a range of perspectives on well-being dimensions |

| Phase 8 | Preparation of questions for the semi-structured interviews taking limitation account the overall aim of the research | Questions based on the phenomenological interview approach to analyse the various experience of the interviewees | |

| Phase 9 | Analysis of the results of the semi-structured interviews | Analysis and interpretation of findings using an inductive reasoning | |

| Phase 10 | Data triangulation | Holistic understanding of mature-aged students’ well-being based on the results of the scientific literature analysis, survey and semi-structured interviews | Based on triangulation results, the recommendations to the faculty are developed on how to support the well-being of mature-aged STEM students to promote sustainability |

| Well-Being Dimension | Survey Indicator (1 = Strongly Disagree … 5 = Strongly Agree) | Code | Mean | Std | Mode | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic | I am satisfied with the quality and availability of the teaching staff. | Q1 | 3.65 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| The content of the courses is current and meets my needs. | Q3 | 3.56 | 1.06 | 3 | 4 | |

| I feel included and supported in my academic environment by the University staff. | Q5 | 3.84 | 1.29 | 5 | 4 | |

| Financial | I can afford additional educational activities (e.g., seminars, courses, materials). | Q14 | 3.37 | 1.38 | 4 | 4 |

| Physical | The academic load negatively affects sleep quality and energy levels. | Q19 | 2.54 | 1.29 | 1 | 2 |

| I often experience physical fatigue or burnout related to my studies. | Q20 | 2.65 | 1.38 | 1 | 3 | |

| Psychological Resilience | I can effectively deal with the stresses of my studies. | Q21 | 3.29 | 0.95 | 3 | 3 |

| Academic requirements significantly affect my psychological well-being. | Q24 | 2.83 | 1.08 | 4 | 3 | |

| Relational | I have developed positive and supportive relationships with instructors | Q26 | 4.01 | 1.06 | 5 | 4 |

| I generally feel socially included and supported in the academic environment. | Q27 | 3.93 | 1.13 | 4 | 4 | |

| I feel that I am generally listened to and respected at the University. | Q30 | 3.7 | 1.32 | 5 | 4 |

| Well-Being Dimension | Survey Indicator (1 = Strongly Disagree … 5 = Strongly Agree) | Program Level | High Endorsement 4–5n (%) | Low Endorsement 0–1n (%) | χ2 (df = 10) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic | The content of the courses is current and meets my needs | College (n = 12) | 5 (41.7%) | 3 (25.0%) | 19.4 | 0.034 * |

| Bachelor (n = 51) | 25 (49.0%) | 5 (9.8%) | ||||

| Master (n = 42) | 20 (47.6%) | 1 (2.4%) | ||||

| Academic | I feel included and supported in my academic environment by the university staff | College | 5 (41.7%) | 5 (41.7%) | 46.2 | <0.001 ** |

| Bachelor | 36 (70.6%) | 6 (11.8%) | ||||

| Master | 28 (66.7%) | 5 (11.9%) | ||||

| Relational | I feel that I am generally listened to and respected at the university | College | 6 (50.0%) | 5 (41.7%) | 23.7 | 0.008 * |

| Bachelor | 29 (56.9%) | 6 (11.8%) | ||||

| Master | 25 (59.5%) | 6 (14.3%) |

| Area of Faculty Responsibility | Related Well-Being Dimension | Recommendations for Faculty |

|---|---|---|

| Faculty as a person with a personality | Relational well-being | Foster respectful, empathetic and open communication with mature-aged students Be accessible outside class hours for academic guidance Adjust academic requirements to reduce unnecessary stress Introduce a culture of mutual learning by allowing mature-age students to share their experiences |

| Study content | Academic well-being, psychological well-being | Adapt curricula to reflect the needs and prior knowledge of mature-aged students Avoid overly complex or irrelevant content Incorporate adult learning principles to minimise cognitive overload |

| Additional networking and experience | Relational well-being, financial well-being, academic well-being | Provide networking and development activities that strengthen social inclusion Reduce financial barriers by offering affordable of free opportunities Respect mature-aged students’ time constraints linked to family or employment |

| Inclusion in the study environment | Relational well-being, psychological well-being | Promote an inclusive academic environment that values age diversity Encourage collaboration between students of different age groups Identify students at risk of isolation and offer targeted support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jekabsone, I.; Snebaha, I.; Ulmane-Ozolina, L.; Strazdina, I.; Kulberga, I.; Budniks, L.; Spjute, L.; Treija, R. Addressing the Challenges of STEM Mature-Aged Students: Faculty Role in Promoting Sustainability and Well-Being in Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121665

Jekabsone I, Snebaha I, Ulmane-Ozolina L, Strazdina I, Kulberga I, Budniks L, Spjute L, Treija R. Addressing the Challenges of STEM Mature-Aged Students: Faculty Role in Promoting Sustainability and Well-Being in Higher Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121665

Chicago/Turabian StyleJekabsone, Inga, Inga Snebaha, Lasma Ulmane-Ozolina, Irina Strazdina, Inta Kulberga, Leonards Budniks, Liga Spjute, and Ruta Treija. 2025. "Addressing the Challenges of STEM Mature-Aged Students: Faculty Role in Promoting Sustainability and Well-Being in Higher Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121665

APA StyleJekabsone, I., Snebaha, I., Ulmane-Ozolina, L., Strazdina, I., Kulberga, I., Budniks, L., Spjute, L., & Treija, R. (2025). Addressing the Challenges of STEM Mature-Aged Students: Faculty Role in Promoting Sustainability and Well-Being in Higher Education. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121665