From Outsiders to Insiders: Empowering University Teachers to Foster the Next Generation of Entrepreneurial Graduates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Course Description

2.2. Course Design and Pedagogical Model

2.2.1. Theoretical Frameworks

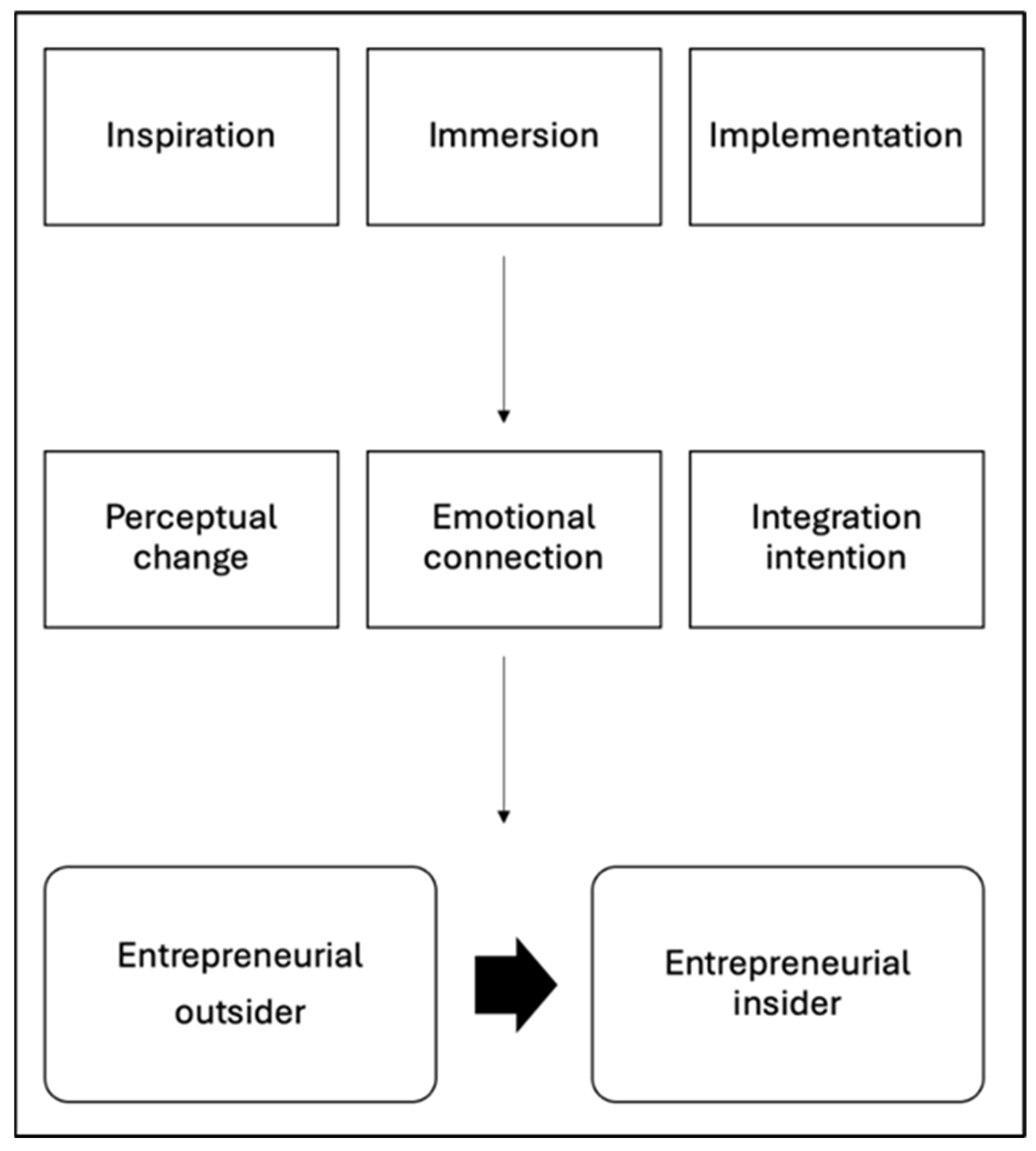

2.2.2. Pedagogical Model

2.2.3. Study Design and Data Collection

2.2.4. Data Analysis

2.2.5. Sample Profiles

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

3.2.1. Perceptual Change

3.2.2. Emotional Connection

3.2.3. Integration Intentions

They [the course facilitators] are impressively good at practicing what they preach. That’s not easy! I have been inspired to incorporate entrepreneurship into my own teaching. There are several useful concepts to take with me: change agents, value creation, looking for opportunities, igniting a spark in the students, getting them to work outside the classroom, and the challenge of tame vs. wicked problems.

I plan to use most of the information you shared in my teaching practice, and plan to adapt resources you used during sessions in my workshops. Additionally, I got inspired by your teaching styles and approaches to teaching, learning and assessment which you used in this course. Thank you!

I did enjoy the course and talking to the other participants, but I still have significant questions regarding the value of entrepreneurship, that I feel were not properly addressed and that would probably result in me not really implementing much, or perhaps, anything that I learned from the course.

I think that the course functions very well, but not for my students who study in a large classroom. If we (the teacher) have to act as change agents for a large classroom, I believe we should have proper tools, training, and techniques that have been successfully applied before.

3.3. Integrating the Two Data Strands

4. Discussion

4.1. Pathways to Educator Transformation

4.2. The Design and Implementation of the Pedagogical Model

4.3. Study Limitations and Future Research Opportunities

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | Cohort No. | Language Format * | No. of Participants | No. of Respondents to S1 * | No. of Respondents to S2 * | No. of Respondents to S1 & S2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 1 | Norwegian | 30 | 26 | 28 | 24 |

| 2 | Norwegian | 17 | 7 | 11 | 6 | |

| 2023 | 3 | Norwegian | 23 | 0 | 15 | 0 |

| 4 | Norwegian | 10 | 8 | 10 | 6 | |

| 5 | English | 13 | 14 | 12 | 11 | |

| 2024 | 6 | Norwegian | 20 | 15 | 20 | 14 |

| 7 | English | 17 | 15 | 14 | 8 | |

| 8 | English, online | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | |

| 9 | English | 8 | 5 | 7 | 5 | |

| 10 | Norwegian | 12 | 10 | 11 | 10 | |

| 11 | English, online | 16 | 17 | 15 | 15 | |

| 2025 | 12 | Norwegian | 20 | 15 | 13 | 12 |

| 13 | English, online | 20 | 6 | 15 | 6 | |

| Total | 212 | 142 | 175 | 119 | ||

| Participant Descriptor | Options | Number | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 69 | 48.6 |

| female | 72 | 50.7 | |

| Would like to self-define | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Age range | Below 30 | 7 | 4.9 |

| 30–40 | 51 | 35.9 | |

| 41–45 | 28 | 19.7 | |

| Over 45 | 56 | 39.4 | |

| Years of professional practice | Under 5 | 18 | 12.7 |

| 6–10 | 26 | 18.3 | |

| 11–15 | 34 | 23.9 | |

| Over 15 | 64 | 45.1 | |

| Prior experience with training in innovation or entrepreneurship | No | 83 | 58.5 |

| Yes | 59 | 41.5 | |

| Teaching/have taught courses focusing on innovation or entrepreneurship | No | 107 | 75.4 |

| Yes | 35 | 24.6 |

References

- Artino, A. R., Jr., La Rochelle, J. S., Dezee, K. J., & Gehlbach, H. (2014). Developing questionnaires for educational research: AMEE Guide No. 87. Medical Teacher, 36(6), 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacigalupo, M., García, L. W., Mansoori, Y., & O’Keeffe, W. (2020). EntreComp playbook: Entrepreneurial learning beyond the classroom. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://speed-you-up.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/jrc120487_entrecomp_playbook.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Bacigalupo, M., Kampylis, P., Punie, Y., & Van den Brande, G. (2016). EntreComp: The entrepreneurship competence framework. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/resources/lfna27939enn.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Baggen, Y., Lans, T., & Gulikers, J. (2022). Making entrepreneurship education available to all: Design principles for educational programs stimulating an entrepreneurial mindset. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 5, 347–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. (2003). Aligning teaching for constructing learning. The Higher Education Academy, 1(4), 1–4. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255583992 (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Blenker, P., Frederiksen, S. H., Korsgaard, S., Müller, S., Neergaard, H., & Thrane, C. (2012). Entrepreneurship as everyday practice: Towards a personalized pedagogy of enterprise education. Industry and Higher Education, 26(6), 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J., Halberstadt, J., Högsdal, N., Kuckertz, A., & Neergaard, H. (2023). Progress in entrepreneurship education and training: New methods, tools, and lessons learned from practice. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, A., Fu, G., Valley, W., Lomas, C., Jovel, E., & Riseman, A. (2016). Flexible learning strategies in first through fourth-year courses. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 9, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano-Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Crișan, E. L., Beleiu, I. N., Salanță, I. I., Bordean, O. N., & Bunduchi, R. (2023). Embedding entrepreneurship education in non-business courses: A systematic review and guidelines for practice. Management Learning, 54(4), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, D., Joseph-Richard, P., & Morgan, M. B. (2021). Integrated, not inserted: A pedagogic framework for embedding entrepreneurship education across disciplines. In Innovation in global entrepreneurship education (pp. 32–51). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. (1997). Experience and education. Simon & Schuster. (Original work published 1938). [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A. (2019). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2014). Entrepreneurship education: A guide for educators. Available online: https://blogs.sch.gr/kglarou/files/2017/08/Guide_Entrepreneurship-Education_2014_EN.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- European Commission. (2016). Entrepreneurship education at school in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Zomeño, A., García-Toledano, E., García-Perales, R., & Palomares-Ruiz, A. (2025). Teachers’ practices in developing entrepreneurial competence for innovative quality education. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(6), 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, H., Lohdi, I. S., & Khan, S. N. (2024). Entrepreneurial competence in academia: A qualitative study of faculty members’ views in higher education institutions. Kurdish Studies, 12(4), 1860–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, K. (2018). Numbers don’t lie: Why microlearning is better for your learners (and you too). Shift eLearning Blog. Available online: https://www.shiftelearning.com/blog/numbers-dont-lie-why-bite-sizedlearning-is-better-for-your-learners-and-you-too (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Harmeling, S. S. (2011). Re-storying an entrepreneurial identity: Education, experience and self-narrative. Education + Training, 53(8), 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, G., & Gabrielsson, J. (2020). A systematic literature review of the evolution of pedagogy in entrepreneurial education research. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(5), 829–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, G., & Kurczewska, A. (2022). Entrepreneurship education: Scholarly progress and future challenges. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, F., & Roald, G. M. (2025). Training university educators to foster embedded entrepreneurship education: An evaluation. Cogent Education, 12(1), 2564255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomah, O., Masoud, A. K., Kishore, X. P., & Sagaya, A. (2016). Micro learning: A modernised education system. Broad Research in Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience, 7(1), 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kakouris, A., & Morselli, D. (2020). Addressing the pre/post-university pedagogy of entrepreneurship coherent with learning theories. In S. Sawang (Ed.), Contributions to management science-entrepreneurship education (pp. 35–58). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Kossen, C., & Ooi, C.-Y. (2021). Trialling micro-learning design to increase engagement in online courses. Asian Association of Open Universities Journal, 16(3), 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackéus, M. (2015). Entrepreneurship in education: What, why, when, how. OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/BGP_Entrepreneurship-in-Education.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Lackéus, M. (2018). “What is value?”—A framework for analyzing and facilitating entrepreneurial value creation. Uniped, 41(1–2), 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackéus, M. (2025). From EntreComp to EntreAct: 16 validated design principles for making people more entrepreneurial. In Y. Baggen, & B. Derre (Eds.), Empowering the next generation of entrepreneurial change agents (pp. 199–220). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, G. D., Waldron, T. L., Gianiodis, P. T., & Espina, M. I. (2019). E pluribus unum: Impact entrepreneurship as a solution to grand challenges. Academy of Management Perspectives, 33(4), 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. R., Jako, R. A., & Anhalt, R. L. (1993). Nature and consequences of halo error: A critical analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(2), 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neergård, G.-B., & Roald, G. M. (2025). Competent to teach? Educators’ perceptions of entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus, D. L. (1991). Measurement and control of response bias. In J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (pp. 17–59). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus, D. L., & Vazire, S. (2009). The self-report method. In R. Robins, C. Fraley, & R. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (pp. 224–239). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Peura, K., & Hytti, U. (2023). Identity work of academic teachers in an entrepreneurship training camp: A sensemaking approach. Education + Training, 65(4), 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., & Jans, L. (2013). A single–item measure of social identification: Reliability, validity, and utility. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(4), 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J. (2008). Entrepreneurship and higher education. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz, A. C. M., Lee, A. Y., Luo, M., Fauville, G., Hancock, J. T., & Bailenson, J. N. (2023). Too tired to connect: Understanding the associations between video-conferencing, social connection and well-being through the lens of Zoom fatigue. Computers in Human Behavior, 149, 107968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Studios Austria. (2005). Available online: https://kmeducationhub.de/research-studios-austria/ (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Roald, G. M., Hellesøy Krogstie, C., Landrø, K., & Wallin, P. (2024). Relasjonsbygging i nettbasert veilederutdanning: En kvalitativ studie av veilederes opplevelser. Nordisk Tidsskrift i Veiledningspedagogikk, 9(2), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roald, G. M., Jin, F., Solvoll, S., & Haneberg, D. H. (Eds.). (in press). Reframing entrepreneurship education: Teaching entrepreneurship in different disciplines. Edward Elgar.

- Schrage, M. (2000). Serious play: How the world’s best companies simulate to innovate. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomassen, M. L., Middleton, K. W., Ramsgaard, M. B., & Neergaard, H. (2020). Conceptualizing context in entrepreneurship education: A literature review. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 26(5), 863–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ewijk, A. R., Nabi, G., & Weber, W. (2021). The provenance and effects of entrepreneurial inspiration. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 27(7), 1871–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanous, J. P., Reichers, A. E., & Hudy, M. J. (1997). Overall job satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(2), 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Mean at T1; T2 | t-Test Result |

|---|---|---|

| Competence | 2.99 (1.31); 3.82 (0.99) | t (117) = 7.70, p < 0.001 |

| Confidence | 3.38 (1.37); 4.09 (0.98) | t (117) = 6.67, p < 0.001 |

| Dimension | Definition | N/Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Perceptual change | Shift in understanding the meaning and relevance of entrepreneurship in their academic contexts. | 41/27.3 |

| Emotional connection | Affective engagement, including feelings of inspiration, confidence, or empowerment. | 43/28.7 |

| Integration intensions | The motivation and commitment to translate new insights and emotions into practice. | 84/56.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, F.; Roald, G.M. From Outsiders to Insiders: Empowering University Teachers to Foster the Next Generation of Entrepreneurial Graduates. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1643. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121643

Jin F, Roald GM. From Outsiders to Insiders: Empowering University Teachers to Foster the Next Generation of Entrepreneurial Graduates. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1643. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121643

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Fufen, and Gunhild Marie Roald. 2025. "From Outsiders to Insiders: Empowering University Teachers to Foster the Next Generation of Entrepreneurial Graduates" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1643. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121643

APA StyleJin, F., & Roald, G. M. (2025). From Outsiders to Insiders: Empowering University Teachers to Foster the Next Generation of Entrepreneurial Graduates. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1643. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121643