Unveiling Mathematical Creativity: The Interplay of Intelligence, Intellect, and Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

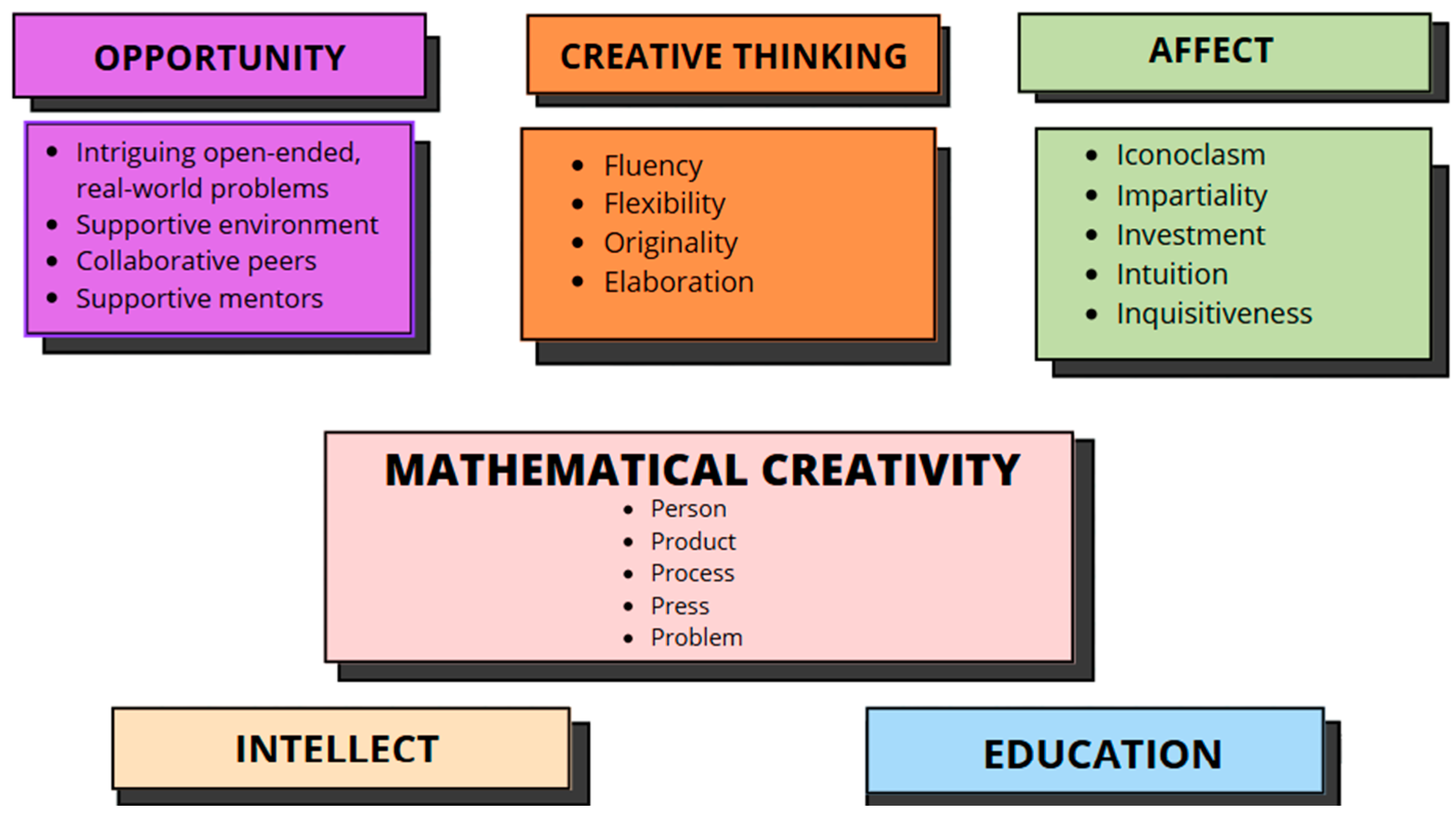

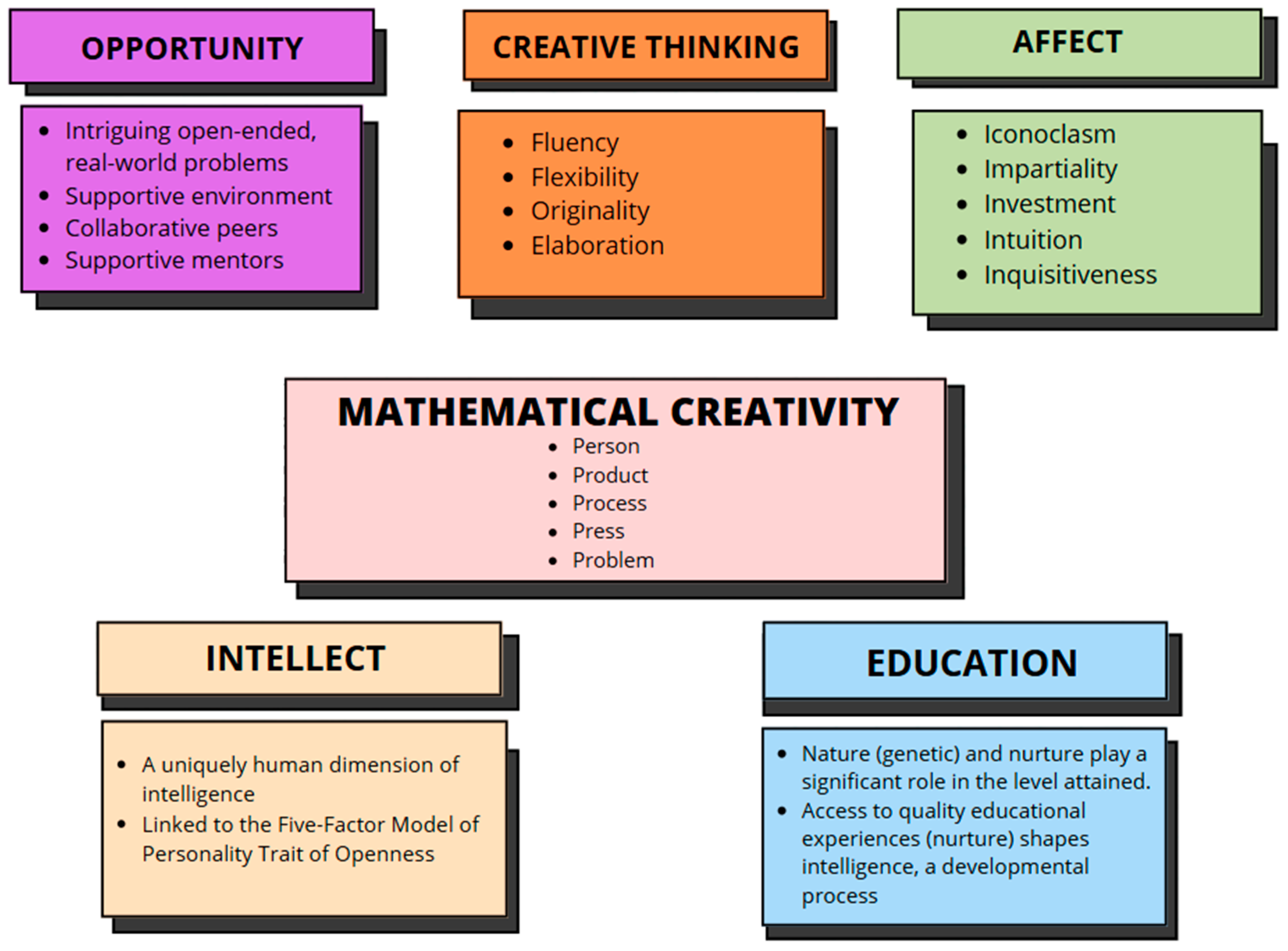

- Person—Traits such as curiosity, openness, risk-taking, and persistence influence creative potential.

- Product—Creative outcomes are novel and valuable relative to the creator’s expertise.

- Process—Iterative and nonlinear, creativity extends beyond standard rules (Wallas, 1926; Pólya, 1962).

- Press—Supportive, collaborative environments foster creativity.

- Problem—Creativity often begins with meaningful, challenging problems, frequently involving generalization or reframing.

- Big-C—Transformative contributions that redefine a field.

- Pro-c—Professional-level creativity developed through extensive training.

- Little-c—Everyday creativity in practical contexts.

- Mini-c—Personally meaningful, novel interpretations often seen in learning.

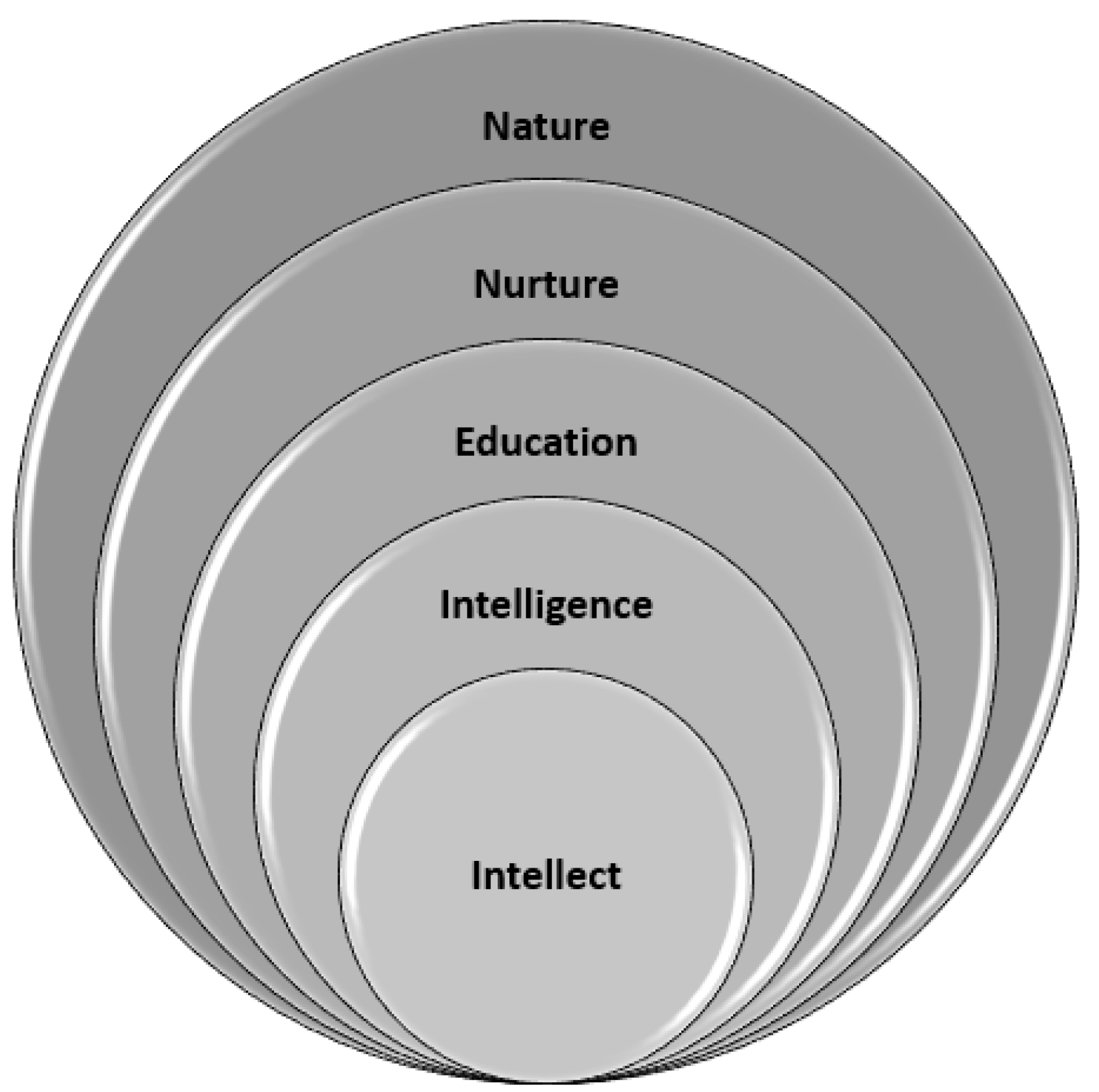

2. Intellect, Education, and Creativity

Intellect n. an individual’s capacity for abstract, objective reasoning, especially as contrasted with his or her capacity for feeling, imagining, or acting.

Intelligence n. the ability to derive information, learn from experience, adapt to the environment, understand, and correctly utilize thought and reason. There are many different definitions of intelligence, and there is currently much debate, as there has been in the past, over the exact nature of intelligence.(p. 252)

2.1. Relationships Between Intellect and Education

Openness, as a high-level construct within the Five-Factor Model of personality traits, includes various facets such as imagination, perceptiveness, and intellect. These facets configure a spectrum of cognitive and behavioral patterns and habits associated with various attributes such as broad-mindedness, creativity, intellectual sophistication, curiosity, cognitive flexibility, receptivity to diverse perspectives and cultural practices, desire for novelty, as well as appreciation for varied experiences, values, and beliefs.

2.2. Relationships Between Intelligence and Creativity

Creativity refers to the abilities that are most characteristic of creative people. Whether or not the individual who has the requisite abilities will produce results of a creative nature will depend upon his motivation and temperamental traits. The creative personality is then a matter of those patterns of traits that are characteristic of creative persons…which include such activities as inventing, designing, contriving, composing, and planning

- Fluency (which includes word fluency, ideational fluency, associationistic fluency, and expressional fluency) is the ability to produce a large number of ideas.

- Flexibility is the ability to produce a wide variety of ideas.

- Originality is the ability to produce unusual ideas.

- Elaboration is the ability to develop or embellish ideas and to produce many details to “flesh out” an idea. (Baer, 1993; as cited in Baer, 2015, p. 71)

Fluid ability has the character of a purely general ability to discriminate and perceive relations between any fundamentals, new or old. It increases until adolescence and then slowly declines. It is associated with the action of the whole cortex. It is responsible for the intercorrelations, or general factors, found among children’s tests and among the speeded or adaptation-requiring tests of adults.

Crystallized ability consists of discriminatory habits long established in a particular field, initially through the operation of fluid ability, but no longer requiring insightful perception for their successful operation.(Cattell, as cited in Schneider & McGrew, 2018, pp. 102, 104).

- There exists a strong correlation between creativity and intelligence.

- Intelligence and creativity are independent concepts.

- The relationship between creativity and intelligence is not linear.

- Intelligence and creativity are subsets of each other.

- Intelligence and creativity are coincident sets.

- Intelligence and creativity are independent but overlapping sets.

- Intelligence and creativity are entirely disjoint sets (pp. 212–213).

2.3. Intelligence, Education, and Creativity

Mathematical creativity is the ability to solve problems and/or develop thinking in structures taking account of the peculiar logico-deductive nature of the discipline, and of the fitness of the generated concepts to integrate into the core of what is important in mathematics.(p. 47)

2.4. Levels of Creativity—Revisiting the Four-C Model

- Big-C Creativity: Eminent creativity that leads to groundbreaking achievements with historical or cultural impact.

- Pro-C Creativity: Professional-level creativity within a specific domain.

- Little-c Creativity: Everyday creativity, solving problems in everyday life.

- Mini-c Creativity: Creativity that is novel and meaningful to the individual.

3. The Relationship Between Mathematical Creativity and Education, Intelligence, and Intellect—A Model to Identify Potential

Two factors relating to Openness (affective engagement and aesthetic engagement) were significantly associated with creative achievement in the arts, whereas two factors relating to Intellect (explicit cognitive ability and intellectual engagement) were significantly associated with creative achievement in the sciences.(p. 249)

… openness/intellect is the core of the creative personality. This means that the best route to understanding why some people are more creative than others is likely to be through research on openness/intellect. If we can understand why openness/intellect is one of the major dimensions of personality, we may better understand the significance of creativity in human functioning. And if we can understand the various components of openness/intellect and their sources in psychological and biological processes, we will be well on our way to understanding what it is about creative people that enables them to create.(p. 11)

4. The Relationship Between Mathematical Creativity and Education, Intelligence, and Intellect—A Model to Understand Mathematically Creative/Productive Adults

Level 0—Early childhood educationLevel 1—Primary educationLevel 2—Lower secondary educationLevel 3—Upper secondary educationLevel 4—Post-secondary non-tertiary educationLevel 5—Short-cycle tertiary educationLevel 6—Bachelor’s or equivalent levelLevel 7—Master’s or equivalent levelLevel 8—Doctoral or equivalent level

4.1. High Intelligence/High Education (HI/HE)

4.2. High Intelligence/Low Education (HI/LE)

4.3. Low Intelligence/High Education (LI/HE)

4.4. Low Intelligence/Low Education (LI/LE)

5. A Revised Model of Contributing Factors in Mathematical Creativity

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APA | American Psychological Association |

| C | Conscientiousness—one of the Big Five Traits of Personality |

| CHC | Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory of intelligence |

| g | General Intelligence |

| gf | Fluid Intelligence |

| gc | Crystalized Intelligence |

| HE | High Education |

| HI | High Intellect |

| LE | Low Education |

| LI | Low Intellect |

| IQ | Intelligence Quotient |

| NCTM | National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (United States) |

| O | Openness—one of the Big Five Traits of Personality |

| SOI | Structure of the Intellect |

Appendix A

- Core drivers:

- ○

- Intelligence (g): supports abstraction, working memory, problem transformation.

- ○

- Education: supplies concepts, tools, heuristics, and domain knowledge.

- ○

- Openness to Experience: fuels curiosity, tolerance for ambiguity, and exploration.

- Key mechanisms:

- ○

- Mediation: Education partially mediates the effect of Intelligence on creativity (smarter learners acquire more & deeper math).

- ○

- Moderation: Openness amplifies the creative payoff of both Intelligence and Education (open individuals use knowledge more flexibly).

- ○

- Three-way synergy: When all three are high, the likelihood of original mathematical output is maximized.

- Expect β1, β2, β3 > 0; β4, β5, β6 > 0; and a small but positive β7.

- Optional mediation test: Int → Edu → MC (include Edu as mediator in SEM).

| Intelligence | Education | Openness | Expected Mathematical Creativity | Why |

| Low | Low | Low | Very Low | Few tools, limited exploration. |

| Low | Low | High | Low–Moderate | Openness sparks attempts but hits knowledge/skill limits. |

| Low | High | Low | Low–Moderate | Knowledge present, but little flexible use. |

| Low | High | High | Moderate | Openness leverages schooling despite lower g. |

| High | Low | Low | Low–Moderate | Raw ability without tools/habits limits output. |

| High | Low | High | Moderate–High | Openness turns ability into novel strategies even with sparse schooling. |

| High | High | Low | High | Strong ability + tools; creativity constrained by low exploration. |

| High | High | High | Very High | Synergy: rich knowledge, strong ability, exploratory style. |

(Weights reflect main effects > interactions; adjust for your context.)

- Intelligence: fluid-reasoning subtests or short g-battery.

- Education: highest math level + concept inventory/placement + problem-solving heuristics checklist.

- Openness: short Big-Five Openness scale; add curiosity/tolerance for ambiguity.

- Creativity (MC): divergent mathematical thinking tasks (multiple-solution, prob-lem posing), judged for novelty, usefulness, elegance.

- The Int × Open and Edu × Open interactions are positive: openness boosts returns to ability and schooling.

- The Int → Edu → MC indirect path is significant.

- The “all-high” cell outperforms the additive expectation (three-way synergy).

| 1 | Catalyzing Change, https://www.nctm.org/change/ (accessed on 20 April 2025). |

| 2 | The Ramanujan Journal: An International Journal Devoted to the Areas of Mathematics Influenced by Ramanujan, https://link.springer.com/journal/11139 (accessed on 20 April 2025). |

References

- Abu Raya, M., Ogunyemi, A. O., Rojas Carstensen, V., Broder, J., Illanes-Manrique, M., & Rankin, K. P. (2023). The reciprocal relationship between openness and creativity: From neurobiology to multicultural. Frontier in Neurology, 14, 1235348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association [APA]. (2009). APA concise dictionary of psychology. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, J. (1993). Creativity and divergent thinking: A task-specific approach. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, J. (2015). Domain specificity of creativity. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bahar, A. K., Can, I., & Maker, C. J. (2024). What does it take to be original? An exploration of mathematical problem solving. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 53, 101592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2007). Toward a broader conception of creativity: A case for ‘mini-c’ creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 1(2), 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilalić, M., McLeod, P., & Gobet, F. (2008). Why good thoughts block better ones: The mechanism of the pernicious Einstellung (set) Effect. Cognition, 108, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, N. D., Lechner, C. M., Tetzner, J., & Rammstedt, B. (2020). Personality, cognitive ability, and academic performance: Differential associations across school subjects and school tracks. Journal of Personality, 88(2), 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitenbach, A., & Rizza, D. (2018). Introduction to special issue: Aesthetics in mathematics. Philosophia Mathematica, 26, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, S. J. (1991). How much does schooling influence general intelligence and its cognitive components? A reassessment of the evidence. Developmental Psychology, 27(5), 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepelewicz, J. (2024). Math is still catching up to the mysterious genius of Srinivasa Ramanujan. Available online: https://www.quantamagazine.org/srinivasa-ramanujan-was-a-genius-math-is-still-catching-up-20241021/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Chamberlin, S. A., & Mann, E. L. (2021). The relationship of affect and creativity in mathematics: How the five legs of creativity influence math talent. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, I. E. (2011). The paradox of human expertise: Why experts get it wrong. In N. Kapur (Ed.), The paradoxical brain (pp. 177–188). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, J. J., & Reingold, E. M. (2014). The Einstellung effect in anagram problem solving: Evidence from eye movements. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervynck, G. (1991). Mathematical creativity. In D. Tall (Ed.), Advanced mathematical thinking (pp. 42–53). Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, D. Y., & Harris, J. (1992). The elusive definition of creativity. Journal of Creative Behavior, 26, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatzka, T., & Hell, B. (2018). Openness and postsecondary academic performance: A meta-analysis of facet-, aspect-, and dimension-level correlations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(3), 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 3, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J. P. (1956). The structure of intellect. Psychological Bulletin, 53(4), 267–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadamard, J. (1945). The psychology of invention in the mathematical field. Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Halmos, P. R. (1985). I want to be a mathematician. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hegelund, E., Grønkjær, M., Osler, M., Dammeyer, J., Flensborg-Madsen, T., & Mortensen, E. (2020). The influence of educational attainment on intelligence. Intelligence, 78, 101419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfand, M., Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2017). The four C model of creativity: Culture and context. In V. P. Glăveanu (Ed.), Palgrave handbook of creativity and culture research (pp. 15–360). Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, T. (2000). The influence of overcoming fixation in mathematics towards divergent thinking in open-ended mathematics problems on Japanese junior high school students. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 31, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauk, E., Benedek, M., Dunst, B., & Neubauer, A. C. (2013). The relationship between intelligence and creativity: New support for the threshold hypothesis by means of empirical breakpoint detection. Intelligence, 41, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four C model of creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2013). In praise of Clark Kent: Creative metacognition and the importance of teaching kids when (not) to be creative. Roeper Review, 35(3), 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J. C., Waterstreet, M. A., Ailabouni, H. S., Whitcomb, H. J., Roe, A. K., & Riggs, M. (2010). Personality and self-perceptions of creativity across domains. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 29(3), 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, S. B., Quilty, L. C., Grazioplene, R. G., Hirsh, J. B., Gray, J. R., Peterson, J. B., & DeYoung, C. G. (2016). Openness to experience and intellect differentially predict creative achievement in the arts and sciences. Journal of Personality, 84(2), 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, J. S., Chamberlin, S. A., & Mann, E. (2019). Factors that influence mathematical creativity. The Mathematics Enthusiast, 16, 505–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutetskii, V. A. (1976). The Psychology of mathematical abilities in school children. The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leikin, R. (2013). Evaluating mathematical creativity: The interplay between multiplicity and insight. Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, 55, 385–400. [Google Scholar]

- Liljedahl, P., & Sriraman, B. (2006). Musings on mathematical creativity. For The Learning of Mathematics, 26, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, E. L. (2006). Creativity: The essence of mathematics. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 30(2), 236–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, E. L. (2020). Mathematics. In M. Runco, & S. Pritzker (Eds.), Encyclopedia of creativity (3rd ed., pp. 80–85). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, M. A., Burgstaller, J. A., Benedek, M., Vogel, S. E., & Grabner, R. H. (2021). Mathematical creativity in adults: Its measurement and its relationship to intelligence, mathematical and general creativity. Journal of Intelligence, 9(10), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, M. A., Ehrengruber, A., Spitzley, L., Eller, N., Reiterer, C., Rieger, M., Skerbinz, H., Teuschel, F., Wiemer, M., Vogel, S., & Grabner, R. (2024). The prediction of mathematical creativity scores: Mathematical abilities, personality, and creative self-beliefs. Learning and Individual Differences, 113, 102473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, R. S. (2011). Developing intelligence through instruction. In R. J. Sternberg, & S. B. Kaufman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of intelligence (pp. 107–129). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, T., Carraher, D., & Schliemann, A. (1985). Mathematics in the streets and in schools. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 3, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleynick, V. C., DeYoung, C. G., Hyde, E., Kaufman, S. B., Beaty, R. E., & Silvia, P. J. (2017). Openness/intellect: The core of the creative personality. In G. J. Feist, R. Reiter-Palmon, & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity and personality research (pp. 9–27). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT (Aug 20 version) [Large language model]. Available online: https://chat.openai.com/chat (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Palanca-Castan, N., Sánchez Tajadura, B., & Cofré, R. (2021). Towards an interdisciplinary framework about intelligence. Heliyon, 7(2), e06268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poincaré, H. (1913). The foundations of science. The Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pólya, G. (1962). Mathematical discovery: On understanding, learning, and teaching problem solving (Vol. 1). John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Pólya, G. (1945). How to solve it: A new aspect of mathematical method. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, M. (1962). An analysis of creativity. The Phi Delta Kappan, 42(7), 305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Sadak, M., Incikabi, L., Ulusoy, F., & Pektas, M. (2022). Investigating mathematical creativity through the connection between creative abilities in problem posing and problem solving. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 45, 101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W. J., & McGrew, K. S. (2018). The Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory of cognitive abilities. In D. P. Flanagan, & E. M. McDonough (Eds.), Contemporary intellectual assessment: Theories, tests, and issues (4th ed., pp. 73–163). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spearman, C. (1927). The abilities of man: Their nature and measurement. The MacMillan Company. [Google Scholar]

- Sriraman, B. (2009). The characteristics of mathematical creativity. ZDM Mathematics Education, 41, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriraman, B., Yaftian, N., & Lee, K. H. (2011). Mathematical creativity and mathematical education. In B. Sriraman, & K. H. Lee (Eds.), The elements of creativity and giftedness in mathematics (pp. 119–130). Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Su, F. (2021). Mathematics for human flourishing. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suherman, S., & Vidákovich, T. (2022). Assessment of mathematical creative thinking: A systematic review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 44, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanberg, A. B., & Martinsen, Ø. L. (2010). Personality approaches to learning and achievement. Educational Psychology, 30(1), 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. J., & Sarnecka, B. W. (2015). Exploring the relation between people’s theories of intelligence and beliefs about brain development. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thørrisen, M. M., & Sadeghi, T. (2023). The Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI): A scoping review of versions, translations, and psychometric properties. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1202953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thørrisen, M. M., & Sadeghi, T. (2025). Personality and education: Associations between personality dimensions, academic field of study, and performance in upper secondary school and higher education. Cogent Psychology, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrance, E. P. (1974). Norms technical manual: Torrance tests of creative thinking. Ginn and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Torrance, E. P. (1979). The search for satori and creativity. Creative Education Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2011). ISCED 2011 international standard classification of education. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20170106011231/https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/international-standard-classification-of-education-isced-2011-en.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Vestena, C. L. B., Berg, J., Silva, W. K., & Costa-Lobo, C. (2020). Intelligence and creativity: Epistemological connections and operational implications in educational contexts. Creative Education, 11, 1179–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (2004). Imagination and creativity in childhood. (M.E. Sharp Inc., trans). Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 42(1), 7–97, (Original text “Voobrazhenie i tvorchestvo v detskom vozraste”, 1967, Prosveshchenie). Available online: https://lchc.ucsd.edu/mca/Mail/xmcamail.2007_08.dir/att-0149/LSV__1967_2004_._Imagination_and_creativity_in_childhood.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Wallas, G. (1926). The art of thought. C. A. Watts and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson, T. (2021, June). Noticing and wondering: Empowerment in learning. President’s messages, National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Available online: https://www.nctm.org/News-and-Calendar/Messages-from-the-President/Archive/Trena-Wilkerson/Noticing-and-Wondering_-Empowerment-in-Learning/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Zager, T. J. (2017). Becoming the math teacher you wish you’d had: Ideas and strategies from vibrant classrooms. Stenhouse Publishers. [Google Scholar]

| Intelligence (IQ) | Education | Openness (Intellect) | Expected Mathematical Creativity | Why |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Low | Low | Very Low | Few tools, limited exploration. |

| Low | Low | High | Low–Moderate | Openness sparks attempts but hits knowledge/skill limits. |

| Low | High | Low | Low–Moderate | Knowledge present, but little flexible use. |

| Low | High | High | Moderate | Openness leverages schooling despite lower g. |

| High | Low | Low | Low–Moderate | Raw ability without tools/habits limits output. |

| High | Low | High | Moderate–High | Openness turns ability into novel strategies even with sparse schooling. |

| High | High | Low | High | Strong ability + tools; creativity constrained by low exploration. |

| High | High | High | Very High | Synergy: rich knowledge, strong ability, exploratory style. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mann, E.L.; Chamberlin, S.A. Unveiling Mathematical Creativity: The Interplay of Intelligence, Intellect, and Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121614

Mann EL, Chamberlin SA. Unveiling Mathematical Creativity: The Interplay of Intelligence, Intellect, and Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121614

Chicago/Turabian StyleMann, Eric L., and Scott A. Chamberlin. 2025. "Unveiling Mathematical Creativity: The Interplay of Intelligence, Intellect, and Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121614

APA StyleMann, E. L., & Chamberlin, S. A. (2025). Unveiling Mathematical Creativity: The Interplay of Intelligence, Intellect, and Education. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121614