1. Introduction

Emergencies—such as epidemics, natural disasters, armed conflicts, and war-related displacement—disrupt education systems. As a result, children are deprived of stable access to inclusive, adaptive learning environments, which in turn undermines educational resilience (

Oniskovets, 2023). In these crisis contexts, students often experience trauma, social isolation, and significant barriers to engagement and learning. Consequently, educators must quickly adapt pedagogical approaches to address learners’ evolving needs (

Tsega & Ademe, 2024). Flexible Emergency Learning Spaces (FELS) have recently emerged as an adaptive and inclusive educational model designed to sustain learning continuity for displaced students, while promoting social connection and emotional resilience (

Salha et al., 2024).

Given the growing role of FELS in responding to the educational disruptions caused by armed conflicts and large-scale displacement, researchers have increasingly examined pedagogical strategies to enhance their effectiveness in such contexts. Research has highlighted the potential of technological adaptation in education to ensure learning continuity, promote social connection, and strengthen the sustainability and resilience of educational systems during emergencies (

Garlinska et al., 2023). In parallel, collaborative learning has been shown to promote adaptability, well-being, and motivation among learners (

Mali et al., 2023), while peer collaboration among educators offers professional and emotional support in crisis contexts (

Kuznetsova et al., 2024). However, while these strategies are theoretically valued, little is known about the practical ways in which technology integration and collaboration are implemented in emergency settings, the levels of technology use and collaboration achieved, as well as the underlying pedagogical approaches guiding these practices within FELS established during large-scale displacement. In particular, existing research has identified persistent gaps between the pedagogical potential of technology adaptation and integration and its actual use in emergencies, which often remains limited and teacher-centered (

Shamir-Inbal et al., 2023). Similarly, both teacher and learner collaborations face challenges related to limited training, increased workload, and the unstable and rapidly changing conditions typical of emergency educational settings (

Sidi et al., 2023).

Such an emergency context unfolded in Israel in October 2023, when a large-scale armed attack by Hamas triggered widespread evacuations, resulting in thousands of children and adolescents being left without access to formal education. In response, the Ministry of Education established FELS within evacuation centers to provide displaced learners with continued, inclusive and resilient educational opportunities and emotional and social support (

Knesset Research and Information Center, 2023). This study aimed to examine how technological adaptation and adaptive pedagogy were implemented in FELS through teaching and learning practices, and how collaboration among both educators and learners was enacted in these emergency educational settings under crisis conditions.

2. Literature Review

This section first presents theoretical frameworks regarding technology integration and collaboration in emergency education. It then outlines the pedagogical and emotional challenges of teaching and learning in emergencies, reviews findings on technology integration in such contexts, and explores collaborative practices among educators and learners during crises.

2.1. Frameworks for Understanding Technology Integration and Collaboration Practices in Emergency Education

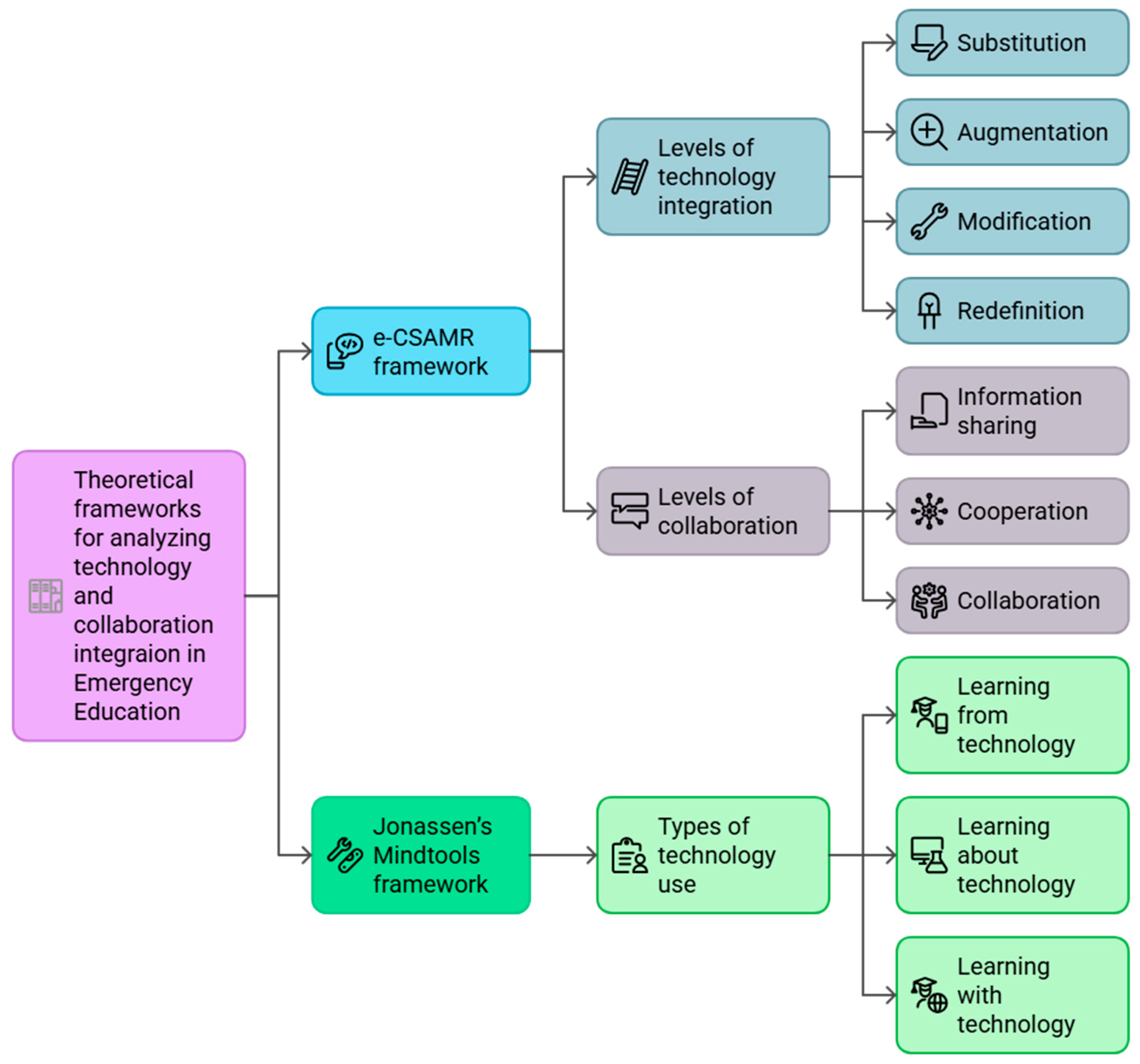

Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical frameworks used to analyze technology integration and collaboration in FELS, which are presented in detail in the following sections.

To analyze how technology and collaboration are integrated in emergency education, this study draws on the e-CSAMR framework (

Shamir-Inbal & Blau, 2021), which builds on

Puentedura’s (

2014) SAMR framework. The framework combines two dimensions: the extent to which digital tools transform teaching practices and the level of peer interaction they support. This combination helps examine not only the technical use of digital tools, but also how they promote collaborative learning processes. The first dimension describes four levels of technology integration.

Substitution represents the most basic level, where digital tools replace traditional materials without fundamentally altering pedagogical approaches.

Augmentation enhances instructional functions through features such as interactive elements, multimedia content, and immediate feedback, though task design remains largely conventional.

Modification enables substantial redesign of learning activities, promoting more active, exploratory, or personalized learning experiences while shifting the educator’s role toward facilitation.

Redefinition supports entirely new forms of learning—including collaborative projects, multimedia creation, and inquiry-based investigations—that enable student agency and promote deeper engagement with content.

The second dimension focuses on learner collaboration (

Blau, 2011;

Salmons, 2008), outlining three levels of interaction. At the basic level,

information sharing involves simple exchanges of ideas without building new knowledge together.

Cooperation includes task division, where learners work on separate parts of an assignment and then combine their efforts, often with limited discussion or joint thinking. At the highest level,

collaboration involves shared inquiry and dialogue, through which students co-construct knowledge and create joint outcomes.

To complement the e-CSAMR framework, this study also applies Jonassen’s Mindtools framework (

Jonassen & Carr, 2020). While e-CSAMR analyzes how technology and collaboration are enacted in practice, it does not fully address the pedagogical purposes or learning theories underlying these practices. Mindtools fills this gap by clarifying why specific technologies are used and how they support different instructional goals. Together, the two frameworks provide a more comprehensive lens on both the implementation and intent of technology-supported learning in emergencies. Jonassen’s framework identifies three types of technology use, each based on a different learning theory.

Learning from technology, grounded in behaviorist and cognitivist approaches, involves structured instruction and guided practice (e.g., tutorial videos, drill-and-practice tools).

Learning about technology, rooted in the cognitive theory, helps students understand and critically engage with digital tools (e.g., learning how visual programming platforms work).

Learning with technology, influenced by constructivist and socio-constructivist perspectives, positions digital tools as thinking partners that support inquiry, collaboration, and knowledge building (e.g., concept maps, shared writing platforms, simulations). In emergency contexts, these distinctions are particularly relevant, as they underscore how the pedagogical orientation of technology use can either limit or enrich learning experiences.

Together, the e-CSAMR and Mindtools frameworks provide a comprehensive analytical lens for examining how technology and collaboration operate within FELS that must rapidly adapt under crisis conditions. By integrating these frameworks, the present study directly addresses a key gap in the literature-understanding how educators and learners in wartime FELS employ technology and collaborative processes between teachers and students not only to sustain instruction but also to enhance resilience and emotional stability.

2.2. Teaching and Learning in Emergencies

Emergencies—such as wars, natural disasters, and epidemics—disrupt education across multiple dimensions, with emotional distress posing a major obstacle to student engagement (

Salha et al., 2024;

Vyortkina, 2023). Learners experience trauma, bereavement, fear, and uncertainty, which impair their ability to learn (

Buda & Czékmán, 2021;

Pyżalski et al., 2022;

Tsega & Ademe, 2024). In addition, the disruption of peer relationships heightens emotional strain and leads to isolation (

Avissar, 2023). Displaced students, those who have been evacuated as a result of crisis situations, often experience additional stress related to adapting to host environments, where social acceptance may be uncertain or diminish over time (

Pyżalski et al., 2022). Together, these emotional challenges significantly hinder learning participation during emergencies.

Alongside emotional distress, students in emergencies face academic challenges that disrupt learning continuity. Concentration and participation are often impaired by psychological strain and daily stressors (

Martynets et al., 2024;

Meshko et al., 2023), while motivation drops as students focus on the crisis (

Schenzle & Schultz, 2024). Moreover, external disruptions—such as blackouts and air raids—obstruct task completion and consistent learning (

Fábián et al., 2024), in addition, irregular attendance exacerbates these effects (

Shamir-Inbal et al., 2023). Collectively, these factors limit academic learning in emergencies.

While education remains essential in crises, its delivery is constrained by personal and structural barriers. School closures due to safety threats, along with trauma, displacement, and loss, prevent many teachers from continuing to teach (

Bugrov et al., 2023;

Zayachuk, 2025). Those who remain face emotional strain, caregiving responsibilities, and limited time for preparation (

Akkad & Henderson, 2024;

Schenzle & Schultz, 2024). In addition, many lack training in trauma-informed and adaptive pedagogy (

Akkad & Henderson, 2024;

Sidi et al., 2023), and even when available, training may be delayed or increase overload (

Akkad & Henderson, 2024;

González et al., 2023;

See, 2024). Such conditions obstruct the continuity of supportive education in crisis.

Building on these difficulties, the pedagogical and emotional disruptions caused by emergencies demonstrate that education systems must provide not only instructional but also psychosocial responses, requiring teachers to adapt their practice under difficult and rapidly changing conditions. In this context, Despite the constraints, many teachers continue to support students emotionally and academically during emergencies (

Rogge & Seifert, 2025;

Rybinska et al., 2023). This support involves integrating emotional care into instruction through empathy, active listening, and opportunities for processing the crisis (

Pyżalski et al., 2022;

Zhang et al., 2023). Family and peer reinforcement also help reduce distress and maintain engagement (

Danylchenko-Cherniak, 2023;

No, 2024;

See, 2024), while education systems offer stability and mitigate isolation (

Tsega & Ademe, 2024). Emotional care thus forms a critical foundation for learning in emergencies.

In parallel, adaptive pedagogical strategies are key to sustaining student engagement during crises. Among these strategies, flexible learning spaces—improvised environments such as shelters, tents, or community centers established in emergency contexts—offer a practical solution for maintaining educational routines. These spaces ensure continuity, safety, and structure, helping stabilize disrupted education (

Salha et al., 2024). Furthermore, collaborative learning and peer interaction enhance participation and promote social connection (

Drobotun et al., 2023). In addition, student-centered approaches—such as inquiry-based tasks, personalized support, and creative activities like music and visual arts—boost motivation and support emotional expression (

Rybinska et al., 2023;

Zamkowska, 2024). Likewise, technology enables communication and instructional continuity when face-to-face teaching is not possible (

Londar & Pietsch, 2023). These combined approaches provide a stable foundation for learning amid crisis.

2.3. Technological Adaptation for Resilient Emergency Education

Technology serves as a core enabler of instruction in emergencies. Its integration ensures continuity under disrupted conditions—such as those caused by security threats—while asynchronous formats provide the flexibility required in crises (

Oniskovets, 2023;

Zayachuk, 2025). Pedagogically, digital tools support differentiation by adapting to students’ pace and level, with real-time feedback enhancing responsiveness (

Garlinska et al., 2023). In addition, interactive components—such as games, quizzes, and virtual reality—deepen understanding and promote engagement through active participation (

Garlinska et al., 2023;

González et al., 2023). Moreover, global digital resources expand learning beyond the classroom, offering access to diverse materials and experiences, while LMS like Google Classroom enhance autonomy, task management, and independent study (

Fábián et al., 2024;

Kulić & Janković, 2022). At the same time, technology use encourages teachers’ professional development. Although initial reliance may provoke anxiety or confusion, it often leads educators to expand their technological skills and adopt more interactive approaches (

Choi et al., 2024;

Holik et al., 2023;

Kasperski et al., 2023;

Molnár, 2021). Emergency contexts thus promote innovation in both student learning and digital pedagogy.

Beyond instruction, technology supports students’ emotional and social needs during emergencies. When face-to-face contact is limited, digital tools enable teachers to sustain meaningful communication, reducing anxiety and offering stability (

Sytnykova et al., 2023). In parallel, peer communication—via structured platforms or informal apps like WhatsApp—reinforces social bonds and eases isolation (

Daher et al., 2022). This continuity of connection strengthens emotional stability and peer belonging.

Despite its potential, technology use in emergencies faces key instructional barriers. Limited access to digital tools and stable internet—especially in displacement—poses a central challenge (

Molnár et al., 2020;

Sytnykova et al., 2023). Many teachers also lack the skills needed for effective integration, while emergency pressures cause stress and resistance (

Bertoletti et al., 2023;

Buda & Czékmán, 2021;

Martynets et al., 2024;

Munyanyo & Simuja, 2024;

Rogge & Seifert, 2025;

See, 2024). As a result, technology is often confined to tasks with limited pedagogical value, such as closed-format assignments using text and video materials (

Cabellos et al., 2023). Weak institutional support and rushed training further intensify these gaps (

Sidi et al., 2023). Together, these factors limit the pedagogical impact of technology in crisis contexts.

Students also face multiple obstacles in engaging with digital learning during emergencies. Many lack access to essential devices or reliable internet, especially in disrupted environments (

Drobotun et al., 2023). Device sharing, power outages, or shelling further hinder learning (

González et al., 2023;

Zayachuk, 2025). In addition, students often lack digital literacy and receive little parental assistance due to limited technical knowledge or competing obligations (

Kuznetsova et al., 2024;

Pangkey & Langkay, 2023). Emotional and social disconnection further impedes learning, as virtual communication lacks the immediacy and nuance of face-to-face interaction (

Holik et al., 2023;

Garlinska et al., 2023). Together, these barriers reduce learning effectiveness.

Despite the barriers, several factors promote meaningful technology use in teaching and learning in emergencies. Teachers with prior digital experience adapt more easily (

Sirk, 2024), while those less experienced benefit from professional development, peer and management support, and shared resources (

Niu, 2024). Likewise, parental involvement strengthens student engagement (

Tammets et al., 2024). Such support systems enhance sustainable technology integration in emergency situations.

2.4. Teacher Collaboration During Emergencies

Another essential aspect of emergency education is teacher collaboration, as educators work together to meet rapidly evolving demands. The urgency and complexity of emergency contexts often enable educator collaboration, prompting mutual support in meeting both learner and teacher needs (

Akkad & Henderson, 2024;

Herrera-Seda & Pantić, 2025). These include jointly co-planning lessons and adapting instruction to crisis-specific needs (

Kasperski et al., 2023), as well as collaboratively participating in school-level decision-making enabled by increased institutional autonomy (

Yang et al., 2023). Such collaboration occurs through in-person and remote meetings, as well as asynchronous exchanges on social media and informal platforms. In these settings, teachers co-develop and share resources that address both instructional and emotional needs (

Kuznetsova et al., 2024;

Tammets et al., 2024). In addition, many form knowledge communities to exchange strategies, reflect on experiences, offer mutual support, and discuss context-appropriate teaching (

Yang et al., 2023). Similarly, teachers acquire emergency-specific pedagogical tools through peer learning and mutual support (

No, 2024), while those with greater expertise—such as in remote instruction or psychosocial support—mentor peers through knowledge sharing, co-planning, and feedback (

Acharya & Rana, 2024). These efforts illustrate internal teacher collaboration in times of crisis.

Collaboration often extends beyond school staff. During emergencies, educators work with psychologists, welfare staff, and online learning specialists who provide targeted input and support (

Cahill et al., 2021;

Lee et al., 2024). Teaching assistants help manage increased classroom needs, particularly when working with displaced learners facing language barriers (

Pyżalski et al., 2022). Additionally, teachers support relief efforts through care, logistics, and community aid (

Tsos & Makaruk, 2023). Support also comes from donors and outside institutions through educational materials, emergency funding, infrastructure repair, joint projects, and scholarships (

Kushnir, 2025;

Londar & Pietsch, 2023;

No, 2024). These collaborations broaden the support network available to schools in emergencies.

Collaboration yields a wide array of professional and emotional benefits for teachers. Knowledge-sharing reduces the burden of adapting instruction under pressure (

Choi et al., 2024), while peer learning helps less experienced teachers gain relevant skills (

Acharya & Rana, 2024). Joint planning enhances teachers’ confidence in remote instruction (

Knopik & Domagała-Zyśk, 2022), and emotional support accelerates adjustment and builds resilience (

Kuznetsova et al., 2024). Pedagogically, collaborative teachers use more student-centered and varied instructional approaches, including collaborative learning (

Sirk, 2024;

Tammets et al., 2024). Overall, collaboration improves teachers’ coping, instructional quality, and adaptability in crisis settings.

Nonetheless, teacher collaboration also involves certain challenges. Joint planning often takes more time than individual preparation, which may increase pressure during emergencies (

Tammets et al., 2024). Additionally, learning from peers or experts—though beneficial—can add to the workload already experienced by teachers in crisis situations (

Cahill et al., 2021). Therefore, while collaborative practices are valuable, they must be carefully balanced against the realities of emergency teaching.

2.5. Collaborative Processes Among Students in Emergencies

In addition to teacher collaboration, enabling collaboration among learners is essential for promoting well-being and supporting meaningful learning in emergency settings. Academic collaboration in such contexts includes a range of structured, peer-based learning activities. Within FELS, this was often implemented through pair or small-group work designed around curricular content (

Antonis et al., 2023;

Sirk, 2024), as well as through peer learning activities that encouraged students to explore new content together (

Tan et al., 2022). Teachers also facilitated class discussions that addressed both academic subjects and complex social realities, encouraging students to express ideas, consider diverse perspectives, and develop critical thinking skills (

Daher et al., 2022;

Gurenko & Suchikova, 2023;

Van Der Merwe & Levigne-Lang, 2023). In some cases, learners co-created products that demonstrated their understanding or applied their skills (

Danylchenko-Cherniak, 2023). These collaborative experiences enhanced motivation, engagement, and self-efficacy (

Kalmar et al., 2022;

Mali et al., 2023) and contributed to sustained learner participation during periods of disruption (

Antonis et al., 2023;

Petre, 2022). These practices show how academic collaboration deepened learning and supported continuity during emergencies.

Beyond academic goals, the social aspect of collaboration was also used to strengthen peer relationships and reduce feelings of isolation (

Kasperski et al., 2023). Activities such as group games, structured play, and joint volunteering-like food distribution or community projects-helped strengthen interpersonal bonds and collective resilience (

Tsos & Makaruk, 2023;

Velykodna et al., 2023). Notably, interactions between displaced and host-community students promoted social integration through shared play and learning (

Lee et al., 2024). These experiences enabled students to form new connections, adjust to unfamiliar environments, and participate in developing a supportive classroom culture (

Drobotun et al., 2023;

Pyżalski et al., 2022;

Toros et al., 2024). Such experiences also encouraged openness to diversity and values such as empathy, cooperation, and mutual respect (

Cecchini et al., 2024;

Drobotun et al., 2023). In this way, the social aspect of collaboration contributed to students’ adjustment, peer bonding, and the development of socially connected and respectful classroom cultures.

In addition to supporting peer relationships, collaborative activities in FELS also addressed students’ emotional needs by creating spaces for expression, reflection, and shared support (

Velykodna et al., 2023). Teachers created opportunities for students to speak about their feelings, process the crisis, and offer peer support-either in whole-class discussions or small group settings (

Lopatina et al., 2023). These emotionally supportive interactions were particularly meaningful in the context of displacement and loss, as many students had experienced trauma and were coping with significant uncertainty (

Pyżalski et al., 2022). Emotional collaboration contributed to a sense of safety and connection, enabling learners to express vulnerability in a supported environment (

Osegbue, 2025). These experiences helped reduce anxiety, encouraged empathy, and allowed students to feel seen and supported by their peers and teachers (

Gurenko & Suchikova, 2023;

Mali et al., 2023;

Møgelvang et al., 2023).

Nevertheless, learner collaboration also presents several challenges. Group tasks often require more time and coordination than individual work, placing additional cognitive and logistical demands on students (

Antonis et al., 2023). In hybrid or online settings-common in some emergency responses-difficulties in communication and emotional expression may arise due to the limitations of digital interaction (

Kalmar et al., 2022). Among displaced students, collaboration may initially support integration, but without ongoing facilitation social tensions can develop between evacuees and local peers. These risks underscore the importance of teacher guidance in promoting respectful dialogue and ensuring inclusive participation, particularly for shy or marginalized learners (

Pyżalski et al., 2022). Moreover, some students in emergency learning settings have expressed a need for more meaningful opportunities to collaborate, suggesting that the potential of peer learning is not always fully realized in practice (

Shamir-Inbal et al., 2023). These challenges emphasize the need for thoughtful planning and active teacher involvement to ensure collaboration is both effective and inclusive.

3. Research Aims and Questions

Although the literature highlights the importance of technology adaptation, collaborative teaching and learning processes in emergency contexts, and documents various efforts to implement these practices, significant gaps remain regarding their advanced and effective application, as highlighted in the preceding literature review. Previous studies indicate that implementation often remains at basic levels, constrained by pedagogical, emotional, and organizational challenges. This study seeks to address this gap by exploring how collaborative practices and technology adaptation are actually enacted in FELS established for displaced children and youth during a war, and what adaptive pedagogical considerations guide their use in these settings.

The research questions are:

What types of technologies, if any, are integrated into FELS? What is the level of technology integration according to the e-CSAMR framework in this context? Which pedagogical approaches are reflected in these environments according to the Mindtools framework?

According to the e-CSAMR framework, what are the levels of collaboration among pedagogical teams, if any, in these FELS? Do these environments encourage the highest level of teamwork between educators?

According to the e-CSAMR framework, what are the levels of collaboration among learners, if any, in these FELS? Do these environments enable the highest level of teamwork between learners?

4. Methodology

4.1. Participants and Context

The dataset comprises 43 semi-structured interviews and 13 non-participatory observations conducted in FELS established for displaced populations. Participants included 35 teachers and 8 principals (35 women, 8 men), aged 24 to approximately 70, with 1 to 40 years of experience. They represented both homeroom and subject-matter teachers in core disciplines such as language, mathematics, and English. Due to security threats during the Iron Swords War, many teachers were themselves displaced, teaching in unfamiliar settings with students from various regions—some familiar, others entirely new as evacuees were relocated to different sites. Fourteen participants worked with evacuees from the north and 29 with those from the south. The sample included participants who taught in a variety of public and religious educational frameworks: 18 in elementary schools, 11 in middle schools, and 14 in high schools.

The FELS operated in hotels, hostels, universities, and repurposed buildings. Some consisted of large open areas divided into small groups; others had dedicated classrooms. They operated three to four hours daily. Students often arrived without school supplies, which were donated—from basic materials to, in some cases, laptops. In certain FELS, students were grouped by grade level; in others, mixed-age groupings were used due to logistical constraints (e.g., limited space or staffing). Some groups included students from the same communities, while others brought together children from unfamiliar and diverse regions.

Figure 2 presents the diversity of FELS learning spaces across different dimensions.

4.2. Instruments

A

mixed-methods design integrates qualitative and quantitative analyses (

Creswell, 2021). The combination of methods enables a deeper, richer, and broader understanding of different aspects of the phenomenon under study (

Stoecker & Avila, 2020). The mixed-methods is a research paradigm, combining qualitative and quantitative components to provide a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon. The multiple case study design refers to the approach for participant and site selection, allowing the exploration of patterns across diverse cases. The qualitative approach allowed for an in-depth exploration of participants’ experiences, while the quantitative approach expanded this understanding by revealing the overall view and scope of the phenomenon across all data sources. (

Mondal & Alam, 2025).

Methodological triangulation was applied, combining semi-structured interviews and non-participatory observations to explore pedagogical practices in FELS. The interviews examined three interrelated domains: the use of technological tools, collaboration among educators, and collaborative learning among students. Participants were asked which digital tools they used, for what instructional purposes, and whether their integration reflected a context-specific rationale or added pedagogical value (e.g., “Do you use technological tools in the FELS? If so, which tools and for what purpose?”).

Educator collaboration was examined in terms of whether it occurred, who was involved, and what collaborative practices were used (e.g., “Do you have partners in planning and designing the learning process? If so, who are they and what is the nature of your collaboration?”).

Student collaboration was explored by examining whether it was implemented, through which instructional strategies, and whether these were perceived by teachers as effective in the emergency setting (e.g.,

“How,

if at all,

do you encourage collaboration among students in these settings?”). The full interview protocol is presented in

Appendix A.

Thirteen lessons were observed across various grade levels, focusing on the same themes as the interviews: technology use, educator collaboration, and student collaboration. Observations followed a structured protocol (

Dźwigoł, 2024) and were conducted unobtrusively, allowing for both systematic and emergent insights. The observation protocol is presented in

Appendix B.

4.3. Research Procedure

Following approval from the Ministry of Education’s Chief Scientist and the Institutional Ethics Committee, participants were recruited through dedicated social media groups for teachers, subject or age specific consultation forums, and job-posting channels where FELS principals also shared invitations. We used snowball sampling to recruit additional participants. The sampling strategy aimed to capture a diverse range of Flexible Emergency Learning Spaces established across different regions and contexts, as illustrated in

Figure 2. Recruitment proceeded until adequate variation across sites and participant profiles was achieved, ensuring diversity of the sample.

Most interviews were conducted on Zoom; 17 out of 43 were conducted by phone due to contextual constraints. All participants received prior notice that interviews would be recorded and transcribed for further analysis. They were also informed in advance that both interview and observation data would be reported anonymously, ensuring that no participant could be personally identified. Each interview lasted about one hour. Interviews and observations were conducted between November 2023 and February 2024.

4.4. Data Analysis

The interviews and observations were analyzed using two coding methods and provided a comprehensive understanding, linking field data with theoretical frameworks, as follows:

Top-down coding: Categories were based on the e-CSAMR framework (

Shamir-Inbal & Blau, 2021) included

levels of technology integration (

Substitution,

Augmentation,

Modification,

Redefinition) and

levels of collaboration (

information sharing,

cooperation,

collaboration) and

Jonassen and Carr (

2020) framework, encompassed types of technology use (learning from technology, learning about technology, learning with technology).

Bottom-up coding: Thematic analysis (

Braun & Clarke, 2006,

2021) identified recurring patterns and categories related to technology integration and collaboration between instructors and learners.

To ensure inter-rater reliability, an experienced researcher independently re-coded 25% of the interview and observation data. Inter-rater agreement, calculated using Cohen’s Kappa, yielded a Cohen’s Kappa coefficient of κ = 0.71, which indicates substantial agreement according to

Landis and Koch’s (

1977) criteria.

The unit of analysis in the interviews was a statement (rather than a participant). In the observations, each recorded entry representing a specific classroom event or action served as a distinct unit of analysis (see

Table 1). The coding was non-exclusive, with a single statement potentially belonging to multiple categories. Initials are used in the following tables to denote interviewees while preserving their anonymity.

All analyses were based on proportional distributions (percentages)—that is, the proportion of statements representing each category or subcategory (e.g., Information Sharing, Cooperation, Collaboration) out of the total number of statements within each dataset. After qualitative analysis, we compared data from interviews and observations, focusing on technology integration and collaboration levels. A chi-square test was used to examine differences in frequencies of categories and subcategories.

5. Findings

The following section presents the main categories and subcategories that emerged from the data analysis.

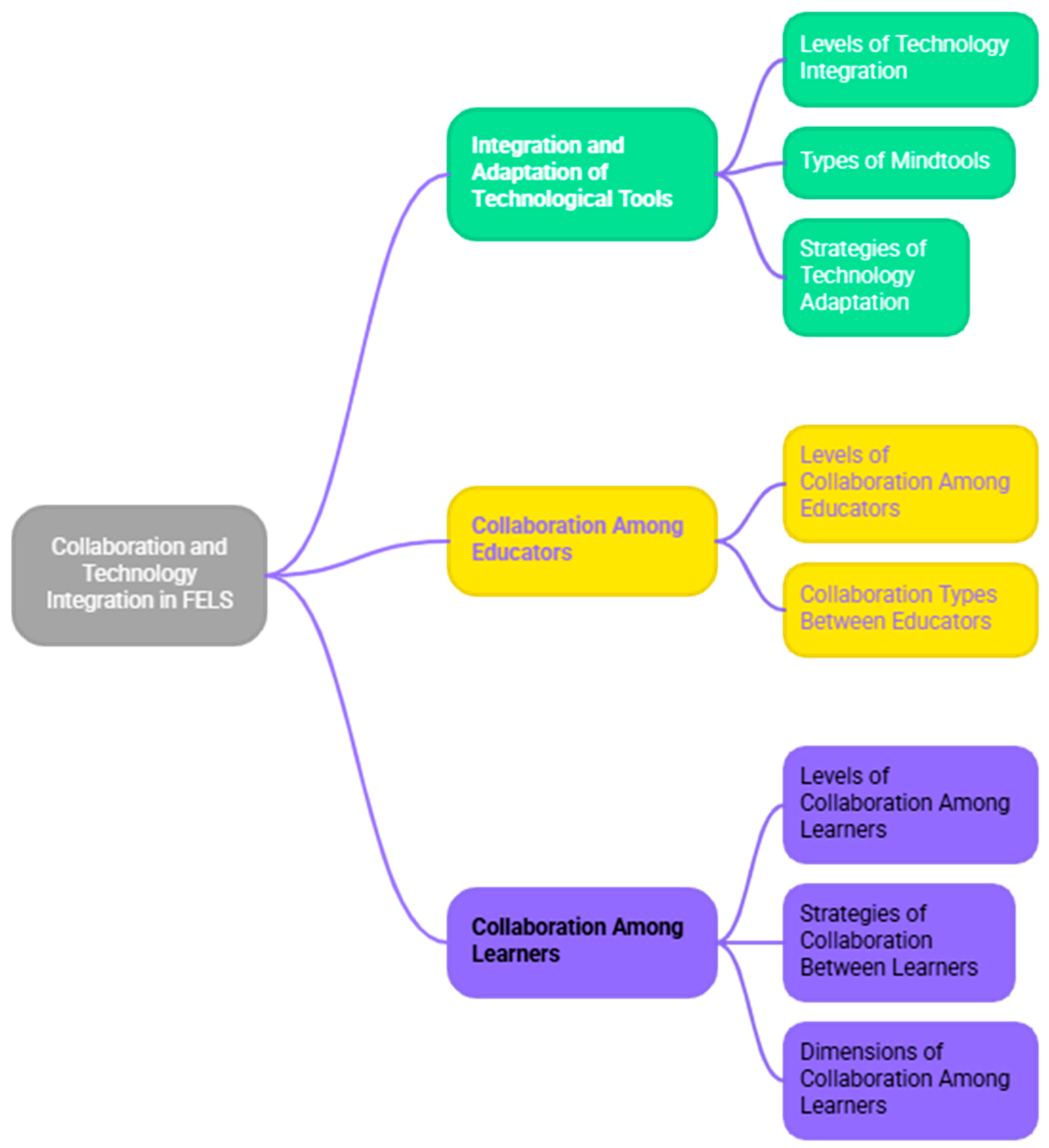

Figure 3 outlines these categories and their hierarchical structure:

The unit of analysis in this study was a statement (rather than a participant), as mentioned in the Data Analysis section. Specifically, the analysis included 475 coded statements from interviews and 85 coded statements from observations. Within these, for technology integration, 109 statements were coded in interviews and 25 in observations; for teacher collaboration, 255 statements were coded in interviews and 35 in observations; and for learner collaboration, 111 statements were coded in interviews and 25 in improvised observations.

5.1. Integration and Adaptation of Technological Tools in Teaching and Learning Processes in FELS

The first question addressed the integration of technological tools in FELS, the level of integration, and the types of mindtools used.

Table 1 presents the levels of technology integration from the interviews and observations, showing the number and percentage of statements for each level based on the e-CSAMR framework (

Shamir-Inbal & Blau, 2021), along with representative quotes from interview or observation notes. It also includes a chi-square comparison between the interview and observation data for each level of integration.

Table 1.

Levels of Technology Integration (N interviews = 109; N observations = 25).

Table 1.

Levels of Technology Integration (N interviews = 109; N observations = 25).

| Levels of Technology Integration | Representative Statements |

|---|

Substitution

Interviews: 31 (28%)

Observations: 8 (32%)

χ2 = 0.09; p = 0.76 | Observation: “Due to the lack of textbooks, the teacher utilized a projector and laptop to present the math problem, allowing all students to view the content and follow the accompanying explanation.” (N) |

Augmentation

Interviews: 43 (40%)

Observations: 10 (40%)

χ2 = 0.0015; p = 0.97 | Interview: “The children practice letter recognition on the computer instead of using workbooks. I introduce a letter or a sound, and then they play games—such as matching the letter or sound to a relevant image. The computer provides immediate feedback, like ‘Well done’ or ‘Try again’.” (K) |

Modification

Interviews: 24 (22%)

Observations: 7 (28%)

χ2 = 0.32; p = 0.57 | Interview: “During a language task, I create a ‘Shazam moment’—students use their phones to search for the meaning of a word, image, or text and compare it to what they initially thought.” (SH) |

Redefinition

Interviews: 11 (10%) | Interview: “A technology company arrived specifically to establish an advanced computer lab, recognizing the urgency of the situation. They donated all the necessary equipment and began teaching the children robotics and makerspace activities.” (L) |

As shown in

Table 1, teachers in the Flexible Emergency Learning Spaces primarily used technology at the basic levels of integration: the most common level of technology integration in both the interviews and the observations was Augmentation—the second level in the hierarchy of integration. In addition, both data sources indicated a notable presence of higher-level integration through Modification. The highest level, Redefinition, appeared only in the interviews. A chi-square analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between the interviews and the observations in the distribution of technology integration levels.

Beyond integration levels, the data were also analyzed using Jonassen’s Mindtools framework.

Table 2 shows the number and percentage of statements for each mindtool type, with representative quotes. A chi-square comparison was also conducted between the interview and observation data for each type.

The analysis of mindtools used by teachers in the FELS revealed that technology integration in FELS primarily reflected behaviorist and cognitive approaches to teaching and learning: the most common type was “Learning from technology”, based on behaviorist and cognitive teaching-learning theories. There was also some use of more advanced tools, such as “Learning with technology” and a small number of statements were categorized as “Learning about technology”. A chi-square analysis showed no statistically significant differences between interviews and observations in the distribution of mindtool types.

Table 3 presents the strategies of technology integration identified in the interviews and observations, including the frequency of statements for each integration strategy alongside representative statements. The strategies are listed in descending order of frequency based on the interview data, with percentages rounded.

Technology adaptation in FELS was commonly implemented through basic strategies, including online practice games, video screenings, and presentation projection. In addition, more advanced uses—such as programming instruction provided by external volunteers and guided online research—were also documented. Certain practices—for example, technology-mediated social interaction, synchronous instruction, and class WhatsApp groups—emerged in interviews but were not observed during classroom visits, as these activities typically occurred outside the FELS environment.

5.2. Collaboration Among Educators in FELS

The second research question examined the occurrence and level of collaboration among educators in the FELS during emergency teaching, based on the e-CSAMR framework.

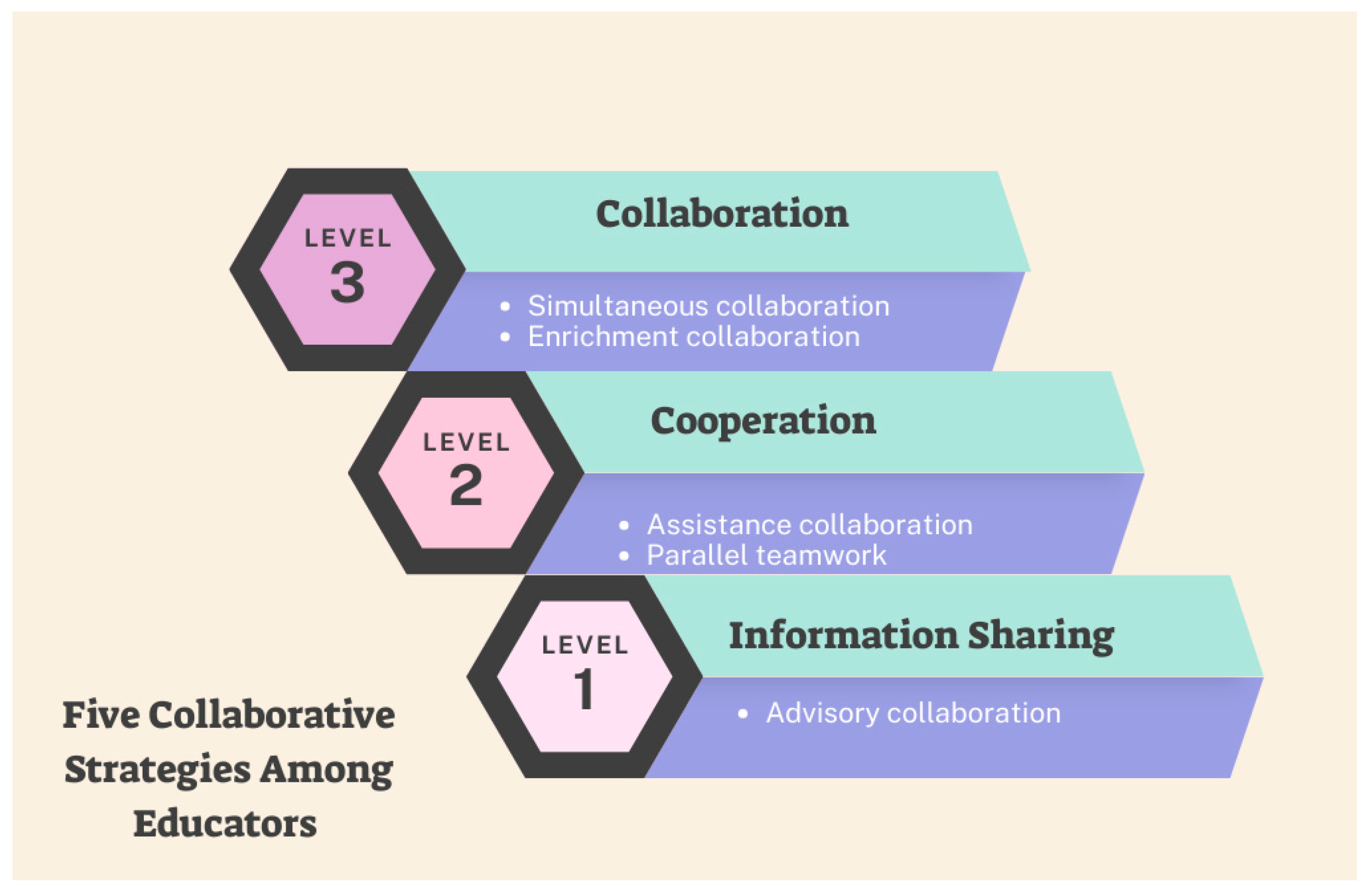

Table 4 outlines the levels of collaboration observed among educators in the FELS, based on the e-CSAMR framework. It presents the number and percentage of statements for each level, as reported in the interviews and observed during classroom observations. Due to the very low frequency of Information Sharing and Collaboration in the observations, the chi-square comparison was conducted solely for this level.

As shown in

Table 4, Cooperation emerged as the most frequently reported level of educator collaboration across both data sources. Notably, in the interview data, all three were represented, with Collaboration (the highest level) being the second most frequently mentioned. This suggests a meaningful emphasis on advanced forms of professional collaboration. However, in the observations, due to insufficient data regarding Information Sharing and Collaboration, these categories were excluded from the chi-square analysis.

In addition to examining the levels of educator collaboration based on the e-CSAMR framework, the analysis also explored the types of collaboration that emerged from the interviews and observations.

Table 5 presents these collaboration types as observed in the FELS, showing the number and percentage of statements alongside representative quotes from both data sources.

Table 5 presents various forms of educator collaboration in the FELS, with the most common being direct assistance to the lead teacher during instruction. Teaching teams included Ministry staff, volunteers, retirees, and academic trainees, which enabled frequent support and informal consultations—especially for novice teachers. Collaboration also occurred through grade-level planning, parallel teaching, and coordination via WhatsApp groups and flexible team meetings.

5.3. Collaboration Among Learners in FELS

The third research question explored whether collaboration occurred among learners in the FELS, and at what levels, based on the e-CSAMR framework.

Table 6 presents the number and percentage of statements related to each level of learner collaboration, as identified in interviews and observations. A chi-square comparison between the two data sources is also included for each collaboration level separately, comparing interviews and observations within each level.

According to the findings presented in

Table 6, collaborative learning was evident across all three levels, with Information Sharing being the most prevalent form in both interviews and observations. Higher levels of collaboration also appeared frequently, particularly at the Collaboration level, suggesting that students were engaged not only in surface-level exchanges but also in deeper forms of joint learning. However, a chi-square analysis of learner collaboration levels revealed no statistically significant differences between the two data sources.

In addition to examining the levels of learner collaboration in FELS, the strategies through which this collaboration occurred were also analyzed.

Table 7 outlines these strategies, including the number and percentage of statements for each, along with a representative quote.

It is evident that in the FELS, teachers incorporated various collaborative activities among learners. The most common form was pair or small-group work, often structured around academic tasks. In addition, teachers frequently facilitated social activities, such as group games and led class discussions that addressed both curricular content and the complex situation in the country.

When analyzing the collaborative learning strategies in the FELS, we observed that educators integrated both cognitive activities, such as working on practice tasks or creating products, alongside emotional and social activities, like discussion circles, group games, and team-building exercises. We categorized these strategies into three dimensions: cognitive, social, and emotional.

Table 8 presents the classification of strategies by dimension, including the number and percentage of statements for each, along with a representative quote.

All three collaboration dimensions were integrated into the FELS. Cognitive collaboration was the most frequent, followed by social collaboration and emotional collaboration in interviews. Yet, emotional collaboration reported in interviews was not observed, suggesting it did not occur in the presence of the observer.

6. Discussion

6.1. Technology Adaptation Approaches in Flexible Emergency Learning Spaces

This study investigated how technology and collaborative practices were implemented by educators and learners in FELS established for displaced children and adolescents during war. Regarding the

first research question, which addressed the levels and strategies of technology integration, the findings revealed that the most prevalent forms were basic-namely, substitution and augmentation. Several factors contributed to this pattern. The FELS were established under emergency conditions, often without access to advanced technological infrastructure. This limitation also affected the teachers themselves, many of whom were displaced and initially lacked personal computers or stable work environments in the evacuation centers. The combination of insufficient institutional resources and personal constraints hindered the implementation of more instructionally effective uses of digital tools. This aligns with previous findings indicating that restricted access-at both the system and individual levels-limits meaningful technology integration during emergencies (

Sytnykova et al., 2023).

Another key factor was the limited pedagogical training among many teachers, which prevented them from implementing higher levels of integration. This corresponds to earlier research identifying teacher expertise as a critical barrier to advanced technology use in crisis contexts (

Martynets et al., 2024;

Rogge & Seifert, 2025;

See, 2024). These findings emphasize the need to develop educators’ capacity to integrate technology effectively in both routine and emergency settings.

In addition to technical and pedagogical limitations, teachers contended with complex emotional and instructional challenges. Many were themselves evacuees, unfamiliar with their students, and responsible for supporting children who had experienced trauma as a result of the crisis and displacement. The students, coming from diverse regions, had no prior relationship with their teachers, which added to the difficulty of building trust and establishing effective classroom dynamics. Faced with these circumstances, educators often lacked the capacity to design time-intensive, learner-centered, and technology-rich lessons. Instead, their immediate priority was to create a sense of stability and emotional safety for their students. These challenges are consistent with prior studies showing that emotional strain during emergencies can impair teachers’ ability to plan and implement complex pedagogical strategies (

Akkad & Henderson, 2024;

Schenzle & Schultz, 2024). They further support findings that stress may contribute to resistance toward more advanced forms of technology use in times of crisis (

Bertoletti et al., 2023). Despite the predominance of basic technology use, several notable cases of advanced integration and adaptation were identified. These initiatives were typically driven by educators with strong technological proficiency or by volunteers who contributed both equipment and expertise. Previous research has shown that teachers with well-developed digital pedagogical skills are more likely to implement higher levels of integration during crises (

Sirk, 2024). In some cases, community support, such as donations and external educational programs, helped facilitate technology-enhanced instruction and contributed to strengthening educational resilience (

No, 2024).

In addition, a number of teachers made a deliberate effort to address the varied needs of their students and to maintain engagement under challenging conditions. For some, this resulted in the adoption of more advanced forms of integration than they had employed in routine settings. Technology was also used flexibly to support students who had not been evacuated, but whose schools were closed due to security threats, as well as those struggling to adjust to the new learning environment. This finding is consistent with prior claims that technology can serve as an adaptive educational tool in times of crisis (

Zayachuk, 2025) and with research suggesting that emergency conditions can act as a catalyst for techno-pedagogical innovation (

Kasperski et al., 2023). Examples of such adaptive practices included the use of synchronous instruction and WhatsApp communication, which appeared in interviews but not in observations, as they took place outside the formal classroom setting. This discrepancy between reported and observed practices suggests that teachers’ technology use extended beyond formal instruction, reflecting their continuous efforts to maintain communication, coordination, and emotional connection with displaced students.

6.2. Collaboration Among Educators

The

second research question explored the extent and nature of collaboration among educators in the FELS. Findings indicated a remarkably high prevalence of teacher collaboration, primarily at the upper levels of the e-CSAMR framework. Educators jointly developed the structure and policies of the newly established spaces and worked closely to address the complex and evolving needs of displaced students. This collaboration was likely prompted by the emotional burden of the emergency, the unfamiliarity between teachers and learners, and the shared sense of responsibility. These findings align with prior research showing that crisis contexts often promote collective professional action (

Akkad & Henderson, 2024).

Beyond pedagogical coordination, collaboration also helped teachers navigate their own emotional burdens. Many educators shared personal challenges, offered mutual support, and exchanged coping strategies for working with distressed students. These emotionally supportive interactions contributed to teacher resilience and a sense of solidarity, reflecting prior studies that highlight the value of peer support in sustaining educators during crises (

Kuznetsova et al., 2024).

This collaborative culture was further strengthened by the active involvement of a wide range of volunteers-including professors, retired educators, student teachers, and artists-who brought diverse expertise and assumed shared responsibilities. Their significant presence in the classroom ensured that several adults were available during each lesson, making it possible to provide more personalized and responsive support to students, both academically and emotionally. Many of these individuals had backgrounds in pedagogy or psychosocial care and served as mentors, supporting teachers in navigating both instructional and emotional challenges. Their involvement reinforces prior research indicating that community engagement can enhance both academic support and emotional care in emergency learning environments (

Lee et al., 2024). Furthermore, the varied professional profiles of staff members, particularly those from artistic and academic fields, enabled the introduction of creative and recreational activities that nurtured students’ emotional well-being during the crisis. Taken together, these collaborative efforts not only supported teacher resilience, but also expanded the range and depth of support provided to learners.

Although the qualitative interviews revealed a wide range of collaborative practices among educators, only one form-Cooperation-was observed during classroom sessions. This pattern was further supported by the quantitative comparison, which revealed a notable gap even within the Cooperation level itself. The alignment between the qualitative and quantitative findings strengthens the conclusion that much of the collaboration described by teachers occurred outside formal instruction and was not reflected in classroom practice. A plausible explanation is that the emotional burden experienced by learners required teachers to focus their full attention on immediate instructional and emotional needs, leaving limited opportunity for in-class consultation or planning. This interpretation is consistent with findings by

Meshko et al. (

2023), who observed that student distress often disrupted classroom participation and, in turn, reduced opportunities for teacher collaboration.

A bottom-up analysis of interview and observational data yielded five distinct forms of educator collaboration:

Advisory Collaboration: providing emotional and professional support to colleagues, including offering advice and substituting for absent peers when necessary.

Parallel Collaboration: multiple teachers simultaneously teaching in the same classroom, each working with different groups.

Assistance Collaboration: lead teacher supported by additional staff during lessons.

Enriching Collaboration: joint lesson planning or developing a shared vision for emergency learning spaces.

Simultaneous Collaboration: co-teaching that integrates each educator’s unique contributions.

These five collaborative configurations correspond to the hierarchical structure of the e-CSAMR framework (

Shamir-Inbal & Blau, 2021), which categorizes educator collaboration based on depth of involvement and shared responsibility (see

Figure 4).

These five collaborative types offer a conceptual framework for understanding teacher teamwork across emergency and routine settings, moving beyond hierarchical levels to describe diverse modes of professional collaboration.

6.3. Collaboration Among Students

The

third research question investigated the presence and depth of collaborative learning processes among students in FELS. Findings indicated that such collaboration occurred at all three levels of the e-CSAMR framework, including instances of high-level engagement. A bottom-up analysis revealed that teachers primarily implemented collaborative strategies within the cognitive dimension, such as pair work, small-group tasks, and whole-class discussions. These efforts aimed to maintain active student involvement despite the disruptions caused by the emergency. This aligns with prior research suggesting that collaborative learning enables sustained participation during crises (

Antonis et al., 2023;

Drobotun et al., 2023). It also reflects teachers’ strong sense of professional responsibility to provide meaningful learning experiences under adverse conditions (

Rybinska et al., 2023). Importantly, students often responded positively, actively participating in these collaborative formats, which may have contributed to a sense of continuity and emotional grounding amid disruption (

Tsega & Ademe, 2024).

In addition to cognitive strategies, teachers also facilitated collaboration in the emotional and social dimensions. Emotionally grounded collaboration took the form of teacher-led sharing circles, while socially focused collaboration was enabled through structured group activities such as board games. These practices were intentionally implemented to respond to the psychological toll of the crisis and the lack of familiarity among students from different regions. By using emotionally grounded activities, teachers aimed to reduce anxiety and enhance a sense of safety, while socially oriented tasks helped build interpersonal bonds and promote peer connection. These findings correspond with prior research highlighting the emotional and social benefits of peer-based collaboration in emergency settings, particularly for displaced learners (

Lopatina et al., 2023;

Mali et al., 2023;

Toros et al., 2024). However, emotional collaboration was not observed during classroom observations, despite 13 h of observation data. It was likely because teachers intentionally avoided initiating emotionally oriented activities in the presence of an observer, out of respect for students’ privacy and emotional sensitivity. This deliberate choice aligns with prior research emphasizing teachers’ strong attentiveness to learners’ emotional needs in emergency contexts (

Velykodna et al., 2023).

6.4. The Extended e-CSAMR Framework-(e)-CDSAMR

To comprehensively analyze teaching and learning processes, we propose expanding the e-CSAMR framework to include both the dimensions of learning (cognitive, social, emotional) and the levels of collaboration alongside technology integration. The resulting framework-the (e)-CDSAMR framework-enables a multifaceted assessment of pedagogical practices in emergency and non-emergency contexts alike. The acronym stands for: C—Collaboration, D—Dimension, S—Substitution, A—Augmentation, M—Modification, R—Redefinition.

Figure 5 presents the structure of the (e)-CDSAMR framework.

Among the three collaboration dimensions, the emotional domain received the least emphasis. A likely explanation is that many teachers lacked either the training or confidence to facilitate emotionally oriented activities, despite their recognized importance in times of crisis. This finding underscores the vital contribution of external professionals who supported teachers in addressing students’ emotional needs. It also highlights the importance of better preparation for educators during routine periods to engage with learners’ emotional well-being in both regular and emergency educational settings. In line with this, prior research has shown that teachers often feel insufficiently prepared to provide emotional support during crises (

Akkad & Henderson, 2024). The findings demonstrate that all three levels of collaboration-Information Sharing, Cooperation, and Collaboration-can be expressed across cognitive, social, and emotional learning dimensions. For instance, within the cognitive domain, Information Sharing may involve class discussion, Cooperation may be reflected in assigning distinct roles within an academic task, and Collaboration may occur when students jointly solve problems. In the social domain, Information Sharing might entail turn-taking in a trivia game, Cooperation could involve completing different parts of a group challenge, and Collaboration may be seen when learners work together toward a common goal against a simulated opponent. In the emotional dimension, Information Sharing could involve expressing personal feelings, Cooperation might include each student formulating a question on an emotional theme to contribute to a group discussion, and Collaboration could be demonstrated through co-creating a product that captures shared emotional experiences.

7. Conclusions

This study examined the integration and adaptation of technology and the collaborative practices of teachers and learners in FELS established during wartime—an area that remains underexplored in the current literature. The study employed a mixed-methods multiple case study design, combining semi-structured interviews and classroom observations in FELS for evacuees. The findings revealed that, although most technology use in FELS occurred at lower levels of integration, it nonetheless encouraged teachers to experiment with more advanced applications. Supported by volunteers, several spaces demonstrated high levels of technology use, which acted as a catalyst for more meaningful digital engagement. In this way, technology integration enabled varied learning formats, provided differentiated responses to learners’ needs, and enhanced motivation and interest—thereby contributing to resilient education. These findings highlight the importance of establishing stable and accessible technological infrastructures in emergency-responsive educational settings, as well as providing ongoing pedagogical support that enables teachers to adopt more innovative and higher-level uses of technology even under crisis conditions.

The emergency context also promoted high levels of teacher collaboration. Multiple forms of cooperation were identified, including joint lesson planning, shared assistance to learners, professional advice, and mutual emotional support among educators. These practices enhanced both instructional quality and teacher resilience. The prominence of emotional support within these collaborative interactions underscores its pedagogical significance: emotional collaboration functioned as a stabilizing force that sustained teachers’ professional functioning, buffered uncertainty, and reinforced collective resilience within the FELS environment. Embedding emotional collaboration within teacher preparation and ongoing professional learning may therefore strengthen educators’ capacity to respond adaptively in emergency contexts.

Finally, learner collaboration was intentionally encouraged by teachers through structured social–emotional activities such as sharing circles, group games, and cooperative learning tasks. These collaborative formats supported interaction and engagement across cognitive, social, and emotional dimensions, nurturing learners’ sense of belonging, security, and well-being, and strengthening both individual and collective resilience in the emotionally challenging circumstances of emergency education. Such findings emphasize the need for institutional practices that recognize the social–emotional foundation of learning as an essential component of emergency pedagogy and that ensure educators are equipped with the training, tools, and supportive conditions necessary to cultivate these collaborative processes effectively.

By applying pedagogical theory through the e-CSAMR and Mindtools frameworks—and by introducing the new e-CDSAMR framework—this study offers both a conceptual lens and a practical resource for analyzing technology-supported and collaborative educational practices across cognitive, emotional, and social domains, in emergencies and beyond. Moreover, this article contributes an expanded conceptual framework that defines not only levels but also distinct types of teacher collaboration applicable across diverse educational contexts. Taken together, these insights reinforce the centrality of both technological readiness and emotionally informed collaboration in constructing resilient emergency learning environments, pointing to concrete directions for strengthening training frameworks, resource allocation, and pedagogical design in future emergency responses.

Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights into technology integration and collaborative practices within FELS during the early stages of an emergency, future research could examine how such practices evolve over time and across diverse educational contexts. Expanding the empirical base may help to further validate the proposed e-CDSAMR framework and support the development of robust, context-sensitive strategies for teaching and learning in both emergency and routine settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B. and O.A.; methodology, I.B. and O.A.; validation, I.B. and O.A.; formal analysis, O.A.; investigation, O.A.; resources, I.B.; data curation, O.A.; writing—original draft preparation, O.A.; writing—review and editing, I.B.; visualization, O.A.; supervision, I.B.; project administration, O.A.; funding acquisition, I.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Research Authority, The Open University of Israel.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Chief Scientist of the Israeli Ministry of Education; Institutional Ethics Committee, The Open University of Israel (Chief Scientist’s Office Approval Code: 12983, Approval Date: 1 November 2023; Institutional Ethics Committee Approval Code: 3459; Approval Date: 20 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are available (in Hebrew) from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to ethical and privacy considerations, the data are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT for language editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the content generated and take full responsibility for the final version of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| FELS | Flexible Emergency Learning Spaces |

Appendix A. Interview Questions for Educators in Flexible Emergency Learning Spaces

* The interview guide includes topics beyond the scope of this article, and not all questions were analyzed or discussed in the present study.

Appendix A.1. Background

Tell me a bit about yourself (e.g., education, teaching experience, seniority).

Could you describe the flexible emergency learning space where you are teaching: Where is it located? What grades and subjects do you teach? How frequently? What does the learning space look like? Is it fixed or changing? To what extent does the space allow for student movement and flexibility between whole-class instruction, group work, or individual learning?

How did you come to teach in this space?

Appendix A.2. Professional Development

Have you participated in any training or received any guidance on teaching in flexible emergency learning spaces during emergencies? You may refer to formal programs as well as informal processes-online or face-to-face. (If clarification is needed, provide examples such as peer learning via social media or in temporary residences, online tutorials, etc.).

(If yes): What teaching tools or strategies did you gain through this training, and how do you implement them in your current teaching?

Appendix A.3. Teaching, Learning, Assessment, and Teacher Role

How do you perceive your role as a teacher in these flexible emergency learning spaces? In what ways, if any, does this differ from your role in a regular classroom during routine times?

What are your teaching goals in this emergency setting, and how do they differ from your goals during routine teaching?

What instructional methods do you use in these flexible spaces, and what is the rationale behind them? How, if at all, do these methods differ from those you use in regular classroom settings?

How has teaching during an emergency influenced your perception of your teaching role?

Do you think certain subjects are better suited to these spaces than others? Please explain.

Appendix A.4. Students

In what ways does student learning in these flexible emergency learning spaces differ from routine learning?

How do students respond to learning in this context?

What unique learning, emotional, or social needs do your students have in these emergency spaces, and how do you address them?

Do you use any assessment methods to evaluate student performance in these settings?

Appendix A.5. Technology Integration

Do you use any technological tools in your teaching in these flexible learning spaces?

(If yes): Which tools do you use and for what purpose?

(Note: This includes the educational use of students’ personal phones. If teaching occurred online, please describe that as well.)

Appendix A.6. Collaboration Among Students and Staff

How, if at all, do you promote collaboration among students in these flexible emergency learning spaces?

Do you collaborate with colleagues in lesson planning? (If yes): Who are your collaborators, and what does this collaboration look like?

Appendix A.7. Perceptions of Success and Final Reflections

What challenges do you see in teaching and learning in flexible emergency learning spaces during an emergency?

What factors have helped or supported effective teaching and learning in these settings?

What, in your view, would constitute successful teaching and learning in these flexible emergency learning spaces during an emergency?

Is there anything you would like to emphasize, clarify, or add that was not addressed in this interview?

Appendix B. Classroom Observation Protocol

* The observation protocol includes topics beyond the scope of this article, and not all elements were analyzed or discussed in the present study.

Type of activity (e.g., discussion, direct teaching, group work, etc.)

Description of the activity

Duration of the activity

During the lesson, was there collaboration among educators? Who were the participants?

How was the collaboration expressed or demonstrated?

How long has the teacher known the students?

Was the teacher–student interaction respectful?

Were there frequent disciplinary issues?

References

- Acharya, B. N., & Rana, K. (2024). How students and teachers voyaged from physical classroom to emergency remote teaching in COVID-19 crisis: A case of Nepal. E-Learning and Digital Media, 21(2), 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkad, A., & Henderson, E. F. (2024). Exploring the role of HE teachers as change agents in the reconstruction of post-conflict Syria. Teaching in Higher Education, 29(1), 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonis, K., Lampsas, P., Katsenos, I., Papadakis, S., & Stamouli, S. (2023). Flipped classroom with teams-based learning in emergency higher education: Methodology and results. Education and Information Technologies, 28(5), 5279–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avissar, N. (2023). Emergency remote teaching and social–emotional learning: Examining gender differences. Sustainability, 15(6), 5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoletti, A., Soncin, M., Cannistrà, M., & Agasisti, T. (2023). The educational effects of emergency remote teaching practices—The case of COVID-19 school closure in Italy. PLoS ONE, 18(1), e0280494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, I. (2011). E-collaboration within, between, and without institutions: Towards better functioning of online groups through networks. International Journal of e-Collaboration (IJeC), 7(4), 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buda, A., & Czékmán, B. (2021). Pandemic and education. Central European Journal of Educational Research, 3(3), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugrov, V., Gozhyk, A., Starostina, A., Bilovodska, O., & Kochkina, N. (2023). Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv: Navigating education as a frontline during times of war. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 21(2), 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabellos, B., Echeverría, M. P. P., & Pozo, J. I. (2023). The use of digital resources in teaching during the pandemic: What type of learning have they promoted? Education Sciences, 13(1), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, J. L., Kripchak, K. J., & McAlpine, G. L. (2021). Residence to online: Collaboration during the pandemic. Journal of Teaching and Learning with Technology, 10, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini, J. A., Carriedo, A., Méndez-Giménez, A., & Fernández-Río, J. (2024). Highly-structured cooperative learning versus individual learning in times of COVID-19 distance learning. European Journal of Teacher Education, 47(1), 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G. W., Lim, J., Kim, S. H., Moon, J., & Jung, Y. J. (2024). A case study of south korean elementary school teachers’ emergency remote teaching. Knowledge Management & E-Learning, 16(2), 259–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2021). A concise introduction to mixed methods research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Daher, W., Mokh, A. A., Shayeb, S., Jaber, R., Saqer, K., Dawood, I., Bsharat, M., & Rabbaa, M. (2022). The design of tasks to suit distance learning in emergency education. Sustainability, 14(3), 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danylchenko-Cherniak, O. (2023). Creative and collaborative learning during Russian-Ukrainian war period: Philological aspects. Philological Treatises, 15(1), 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobotun, V., Kavytska, T., Fortanet-Gómez, I., & Madrid, N. R. (2023). Collaborative online learning (COIL) as a promising pedagogy for engaging students in global collaboration: Ukrainian-Spanish context. Ars Linguodidacticae, 12(2), 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dźwigoł, H. (2024). The role of qualitative methods in social research: Analyzing phenomena beyond numbers (pp. 139–156). Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology Organization and Management Series No. 206. Silesian University of Technology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (2021). What is the Eisenhardt method, really? Strategic Organization, 19(1), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fábián, M., Huszti, I., & Lechner, I. (2024). Studying in the shadow of war: The impact of the Russian-Ukrainian war on the learning habits of students in Transcarpathia. Psychological and Pedagogical Problems of Modern School, 1(11), 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlinska, M., Osial, M., Proniewska, K., & Pregowska, A. (2023). The influence of emerging technologies on distance education. Electronics, 12(7), 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, C., Ponce, D., & Fernández, V. (2023). Teachers’ experiences of teaching online during COVID-19: Implications for postpandemic professional development. Educational Technology Research and Development, 71(1), 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurenko, O., & Suchikova, Y. (2023). The Odyssey of Ukrainian Universities: From quality assurance to a culture of quality education. Management in Education. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkias, D., Neubert, M., & Harkiolakis, N. (2023). Multiple case study data analysis for doctoral researchers in management and leadership. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Seda, C., & Pantić, N. (2025). Exercising teacher agency for inclusion in Challenging times: A multiple case study in Chilean schools. Education Sciences, 15(3), 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holik, I., Kersánszki, T., Molnár, G., & Sanda, I. D. (2023). Teachers’ digital skills and methodological Characteristics of online education. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy (iJEP), 13(4), 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonassen, D. H., & Carr, C. S. (2020). MindTools: Affording multiple knowledge representations for learning (pp. 165–196). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmar, E., Aarts, T., Bosman, E., Ford, C., de Kluijver, L., Beets, J., Veldkamp, L., Timmers, P., Besseling, D., Koopman, J., Fan, C., Berrevoets, E., Trotsenburg, M., Maton, L., van Remundt, J., Sari, E., Omar, L.-W., Beinema, E., Winkel, R., … van der Sanden, M. (2022). The COVID-19 paradox of online collaborative education: When you cannot physically meet, you need more social interactions. Heliyon, 8(1), e08823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasperski, R., Porat, E., & Blau, I. (2023). Analysis of emergency remote teaching in formal education: Crosschecking three contemporary techno-pedagogical frameworks. Research in Learning Technology, 31, 2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knesset Research and Information Center. (2023). Educational services for students evacuated from their homes during the Iron Swords War (Report No. 2_cac8692c-ba92-ee11-8162-005056aa4246_11_20361). Available online: https://fs.knesset.gov.il/globaldocs/MMM/cac8692c-ba92-ee11-8162-005056aa4246/2_cac8692c-ba92-ee11-8162-005056aa4246_11_20361.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Knopik, T., & Domagała-Zyśk, E. (2022). Predictors of the subjective effectiveness of emergency remote teaching during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 14(4), 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulić, D., & Janković, A. (2022). Teachers’ perspective on emergency remote teaching during COVID-19 at tertiary level. Information Technologies and Learning Tools, 89(3), 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushnir, I. (2025). ‘It is more than just education. It’s also a peace policy’:(re) imagining the mission of the European Higher Education Area in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. European Educational Research Journal, 24(1), 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, H., Serdiuk, H., Bazyl, L., Vyshnyk, O., & Sobko, V. (2024). Realities of developing the research competence of teachers-philologists in wartime. Revista Eduweb, 18(1), 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Voutilainen, M. M., & Green, C. (2024). Showcase: Emergency education response education above all’s collaborative projects for Ukraine. HundrED. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londar, L., & Pietsch, M. (2023). Providing distance education during the war: The experience of Ukraine. Information Technologies and Learning Tools, 98(6), 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatina, H., Tsybuliak, N., Popova, A., Bohdanov, I., & Suchikova, Y. (2023). University without Walls: Experience of Berdyansk State Pedagogical University during the war. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 21(2), 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, D., Lim, H., Roberts, M., & Fakir, A. E. (2023). An analysis of how a collaborative teaching intervention can impact student mental health in a blended learning environment. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(3), 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynets, L., Shyba, A., Kochetkova, I., Krupiei, K. S., & Rud, A. (2024). The impact of the war on the development of higher education in Ukraine: Experience for EU countries. Academia, 35/36, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshko, H. M., Meshko, O. I., & Habrusieva, N. V. (2023). The Impact of the War in Ukraine on the Emotional well-being of Students in the Learning Process. Journal of Intellectual Disability—Diagnosis and Treatment, 11(1), 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møgelvang, A., Vandvik, V., Ellingsen, S., Strømme, C. B., & Cotner, S. (2023). Cooperative learning goes online: Teaching and learning intervention in a digital environment impacts psychosocial outcomes in biology students. International Journal of Educational Research, 117, 102114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]