Abstract

Despite the increasing integration of digital tools, female lecturers exhibit a lack of confidence in their digital competencies, which adversely affects their engagement with LMS platforms. Understanding the cause of this disparity is the gap this study intends to fill. A simple random sample of 121 participants from the Faculty of Science was selected, employing a mixed-methods approach with a convergent parallel design. Data were gathered through an online LMS survey and interviews. Quantitative data were analyzed using independent samples t-tests and chi-square tests, while qualitative data were analyzed through thematic analysis with Atlas.ti. The results indicated that 48.7% of female lecturers showed a stronger inclination towards adaptation, whereas male lecturers were more evenly divided between adaptation and appreciation. Most lecturers reported positive experiences with LMS tools. This study advocates for targeted professional development programs to enhance digital competencies and promote collaboration. Universities should adopt and integrate feminist pedagogy principles into their digital teaching practices to create more inclusive and equitable online learning environments. By addressing gender disparities, the research aims to contribute to achieving United Nations’ fifth Sustainable Development Goal on gender equity in higher education, ultimately improving student engagement and learning outcomes.

1. Introduction

Whether learning management systems (LMSs) are used effectively is closely linked to university lecturers’ teaching practices. Lecturers are encouraged to design activities that promote active learning within the LMS to enhance student engagement and learning outcomes (Garutsa, 2025). In this context, Ukaegbu and Zaid (2025) reported that most lecturers who are proficient in using LMSs can create more interactive and engaging learning environments, which is crucial for student success. For instance, the use of interactive engagement LMS features, such as discussion boards, quizzes, and multimedia resources, can significantly enhance the learning experience (Simelane-Mnisi, 2023b). Researchers contend that lecturers must make the most of LMSs’ functionality and leverage engaging elements to improve student satisfaction and educational outcomes.

Research indicates that there are notable gender differences in the use of technology, including LMSs. Historically, men have been perceived as more confident and skilled in using information and communication technology compared to women (Falade, 2023). This sentiment is supported by Inoncillo (2024), who indicated that men may hold more favorable views towards technology, which could influence their engagement with LMSs and the effectiveness of their use. However, Garutsa (2025) suggests that these trends are evolving, with women increasingly engaging with technology and showing preferences for certain types of e-learning and LMS tools. Conversely, Owusu-Bempah et al. (2022) suggest that gender does not significantly influence lecturers’ competence in using LMSs. The inconsistency in existing research regarding gender differences in technology use highlights the need for more nuanced research that considers the contextual factors influencing these trends (Garutsa, 2025). More studies on the use of e-learning and gender-based usage trends in the higher education system must be supported (Al-qdah et al., 2025). It is for these reasons that this study investigates gender equity in LMS competency and usage among lecturers.

The problem studied in this research was determining which lecturers, based on their gender, were proficient in and capable of using LMSs in their teaching environments. An additional challenge was to identify the gender that uses LMSs the most out of the variety of blended/hybrid, fully online and face-to-face delivery methods used in the Faculty of Science. By exploring these issues, the findings underscore the critical need for gender-equitable training initiatives that align with feminist pedagogy principles. Such training is essential for fostering transformative educational practices in online teaching, ultimately contributing to a more inclusive and equitable learning environment for all lecturers.

Feminist pedagogy for online learning is a transformative approach that seeks to create equitable and inclusive learning environments by integrating feminist principles into educational practices (Jiménez Cortés & Triviño Cabrera, 2023). In the context of digital education, feminist pedagogy advocates for the use of open and participatory technologies that enhance collaboration and social interaction among learners (Gonzàlez & Conejo, n.d.). Feminist pedagogy seeks to leverage technology to create inclusive learning environments that respect and empower all participants (Jiménez Cortés & Triviño Cabrera, 2023; Gonzàlez & Conejo, n.d.). In this context, fostering gender-equitable competency among lecturers within LMSs is critical due to the transformative potential of feminist pedagogy. This educational approach aims to address and rectify the power dynamics and inequalities inherent in traditional educational frameworks.

This research aligns with the United Nations’ fifth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 5), which focuses on achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls (United Nations, 2015). We emphasize the importance of creating inclusive online learning environments that recognize and value diverse perspectives through integrating the principles of feminist pedagogy. Feminist pedagogy advocates for collaborative learning, critical reflection, and the dismantling of power hierarchies, which can significantly enhance the digital teaching landscape (Jiménez Cortés & Triviño Cabrera, 2023). Ultimately, this study seeks to contribute to closing the gender gap in digital education and promoting equal opportunities for all in higher education institutions. Its aim is to investigate lecturers’ competency and gender equity in the use of LMSs at a University of Technology (UoT) in South Africa. To achieve this, a survey questionnaire was used to establish differences in the lecturers’ LMS usage, module delivery, and competency in utilizing LMSs. Semi-structured interviews were also used to gain deeper insights into lecturers’ experiences and challenges, complementing the statistical findings.

2. Related Literature

2.1. Gender Differences Concerning the Competency and Usage of LMSs for e-Learning Tools

Investigations into gender differences in the usage of learning management systems (LMSs) reveal a complex landscape. Many academics, regardless of gender, exhibit a lack of confidence in their digital competencies, which negatively impacts their engagement with LMS platforms (Chindomu, 2024). This lack of confidence often results in the underutilization of advanced LMS features. When focusing on gender differences, research indicates that male lecturers tend to perceive the effectiveness of LMSs more positively than their female counterparts, with male respondents scoring significantly higher in perceived effectiveness (M = 61.23) compared to female respondents (M = 46.91) (Inoncillo, 2024). This disparity suggests that male lecturers may feel more competent or confident in utilizing LMS tools effectively.

Conversely, systemic barriers that hinder equitable access to resources, including LMSs, disproportionately affect female lecturers (Chindomu, 2024). This is because female lecturers often belong to socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, which often limit their access to necessary technological tools and reliable internet connectivity. This economic disparity exacerbates the challenges they face in utilizing educational technologies. Socioeconomic status also plays a crucial role in influencing access to technology and the development of digital competencies among female academics (Lubinga et al., 2023). However, a study by Falade (2023) in Nigeria found no significant gender differences in awareness regarding the use of the LMS Edmodo, with a t-value of 1.882 and a p-value of 0.061, indicating similar levels of awareness among male and female lecturers. The results imply that gender does not significantly influence lecturers’ awareness of Edmodo for teaching purposes. This contrasts with some previous studies that suggested men might be more technologically adept than women. It is for these reasons that researchers explore gender differences among lecturers in order to enhance digital competencies, ensure equitable access, and foster a positive perception of LMSs among all lecturers, thereby promoting effective engagement with educational technologies.

2.2. Lecturers’ Preferences for LMS Digital Tools

Integrating LMS digital tools into teaching practices is essential to foster student engagement and learning outcomes (Simelane-Mnisi, 2023b). Notwithstanding this fact, many lecturers struggle to apply their digital skills effectively in practice (Suzer & Koc, 2024). However, lecturers with strong digital skills are more likely to engage students and improve learning outcomes (Ukaegbu & Zaid, 2025). Al-qdah et al. (2025) pointed out that lecturers, regardless of gender, frequently utilize core tools within LMSs, such as content creation features (create file, create item, create folder), assessment tools (tests, assignments), and communication features (video conferencing, discussion board). However, Al-qdah et al. (2025) found that disparities in the utilization of LMS digital tools are more likely to be shaped by personal teaching approaches, the departmental culture, or teaching preferences rather than by gender.

In a study by Tan and Zainal (2020), it was found that male lecturers were more likely to use LMSs for content creation and communication; in contrast, female lecturers reported facing greater challenges in adapting to the system. Moreover, a study by Ukaegbu and Zaid (2025) revealed that male lecturers tend to more actively utilize LMSs for interactive teaching and student engagement, while female lecturers often focus on administrative tasks such as posting results and materials. It is critical that targeted training and support for lecturers, particularly female lecturers, are provided to enhance their confidence and competence in using LMS digital tools. Additionally, we argue that higher education institutions should consider implementing professional development programs that focus on the practical applications of LMS digital skills, fostering an environment that encourages collaboration and the sharing of effective teaching strategies. By addressing these disparities, higher education institutions can promote a more equitable and effective use of digital tools, ultimately leading to improved engagement and learning outcomes for all students.

2.3. Feminist Pedagogy for Online Teaching

Feminist pedagogy is an educational approach aimed at transforming power dynamics and addressing the inequalities inherent in traditional educational settings (Jiménez Cortés & Triviño Cabrera, 2023). Drawing from active pedagogical models proposed by influential scholars such as John Dewey, Paulo Freire, and bell hooks, this approach emphasizes social interaction and culturally structured contexts in the learning process, aligning with socio-cultural constructivism (Gonzàlez & Conejo, n.d.). In the context of online teaching, feminist pedagogy integrates these principles to recognize and address gender inequalities, power dynamics, and the diverse experiences of students. It seeks to create a supportive and inclusive learning environment that values diverse identities and experiences, thereby challenging traditional practices that often marginalize women’s contributions (Gonzàlez & Conejo, n.d.). The phenomenon under investigation can benefit significantly from the principles of feminist pedagogy. Incorporating these principles promotes an equitable online learning environment that empowers lecturers and can also enhance the development of teaching practices that recognize and address gender disparities in digital education, ultimately contributing to a more inclusive academic culture and improved educational outcomes for all.

3. Research Questions

- What are lecturers’ LMS digital competency levels?

- Which delivery methods do lecturers prefer while using the LMS in teaching?

- What are the lecturers’ experiences of utilizing the LMS?

- Did the lecturers encounter any challenges while using the LMS that influenced their competency?

Hypotheses

- H1: There is a significant difference between genders and lecturers’ use of LMSs.

- H2: There is a significant difference between gender and lecturers’ competency level in using digital technologies and LMSs.

- H3: There is a significant association between modes of delivery used by male and female lecturers.

4. Methods

A mixed-methods convergent parallel design was adopted in this study. This approach utilizes both quantitative and qualitative data within a single case study to thoroughly explain (Poth, 2023; Creswell & Creswell, 2022) the gender differences in LMS competency and usage between the lecturers included in this study. A convergent parallel design involves simultaneously collecting quantitative and qualitative data, analyzing these datasets separately, and then merging the results for interpretation (Van Wyk & Taole, 2023). Data were collected using an online LMS survey questionnaire and semi-structured interviews.

Descriptive statistics presented in frequencies and percentages and inferential statistics presented with correlations relating to the independent samples t-test and chi-square test were used to analyze quantitative data with the aid of SPSS version 30.0. The aim of descriptive statistics is to simplify and explain the primary features of a dataset, using the number of times a specific value occurs in the data (Yawe & Mubazi, 2023). The inferential statistics method uses a sample of data to draw conclusions, estimates, and generalizations about larger populations (Bakkabulindi, 2023). Correlation measures the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two variables (Bacon-Shone, 2022). We declare that Scholar GPT 5 was used for support in reporting quantitative data. Napkin AI was used to develop Figure 2. This study received ethical approval from the university for conducting research. Pseudonyms are used for the departments and lecturers.

4.1. Participants

In this study, a simple random sampling was used to select the participants from one subpopulation or Faculty within the broader UoT context comprising seven Faculties. In simple random sampling, each member of the population has an equal chance of being selected (Lumadi, 2023). The participants in this study were lecturers from 14 departments in the Faculty of Science at a UoT. The online survey using Google Forms was distributed to 350 lecturers; however, 125 responded. Of these lecturers, four did not give consent to participate. Lecturers who had completed the online survey questionnaire were chosen. The target population of the study comprised 350 lecturers from the Faculty of Science. The sample size was determined using Cochran’s (1977) formula at a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error, resulting in a required size of 183 respondents after applying the fine population correction.

Of this number, 121 lecturers consented and completed the online survey questionnaire, representing approximately 66% of the targeted sample (or 34.6% of the total population). . The reduced response rate yielded an adjusted margin of error of about 4.1%, which remains statistically acceptable for social science research (Cochran, 1977).

The results in Table 1 indicate a predominance of female lecturers in the Faculty of Science, suggesting that women constitute most academic staff within the study cohort. The age distribution shows that most participants are concentrated in the younger and middle age brackets, reflecting a relatively active and professional dynamic workforce. This implies that the faculty’s teaching staff largely comprise lecturers who are in the early and mid-stages of their academic careers. The distribution of participants across professional ranks further reveals that a substantial proportion occupy junior- or mid-level positions, while a smaller proportion hold a senior role. This suggests that the faculty’s human resource structure is characterized by a broader base of early-career academics. Department representation was notably diverse, with all 14 departments contributing participants, although a few departments exhibited higher participation levels. Such variation may be attributed to differences in the departmental size, discipline focus, or engagement with the research theme. Overall, the demographic profile suggests that the Faculty of Science is both gender-inclusive and academically youthful, features that are often associated with a greater openness to innovation and technology adoption in teaching. Consequently, it may be argued that younger lecturers in the Faculty of Science are more likely to embrace teaching that utilizes technology since they belong to Generation Z. This generation is more accustomed to technology since they grew up in a time when social media, cell phones, and the internet were the primary tools (Nhedzi & Azionya, 2025).

Table 1.

Cross-tabulation of participants’ biographical data.

To perform qualitative research, the researchers used a homogeneous sampling technique, allocating two lecturers to each of the 14 departments to recruit 28 additional lecturers in the Faculty of Science using convenient and purposeful sampling. Convenience sampling was applied to select lecturers who were easy to recruit, easily accessible (Poth, 2023) and who had completed the online survey questionnaire. These lecturers were suitable for the purpose of this study. Then, the purposive sampling method was also employed, based on the characteristics the researchers require in a as it was deemed appropriate about the subject being investigated (Creswell & Creswell, 2022).

4.2. Instrument and Procedure

4.2.1. LMS Survey Questionnaire

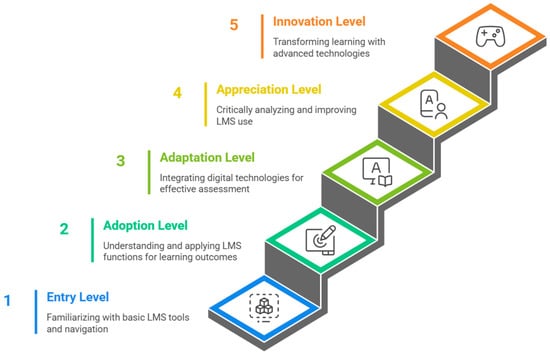

An LMS survey questionnaire with closed-ended questions was used to gather quantitative data for this study. For the closed-ended questions, the respondents were asked to select their choice from a predetermined list of answers, which were usually multiple-choice questions or one-word responses such as “yes” or “no” or “true” or “false” (Maree, 2023). The LMS survey questionnaire created by the researchers consisted of two sections: the purpose of Section A as to collect biographical data. The LMS survey questionnaire was targeted to assess three factors: the use of LMSs, the mode of delivery and the competency level. To assess use of the LMS, the survey featured a “yes” or “no” question, and regarding the mode of delivery applied by the lecturers in 2023 to facilitate learning, the survey required choosing between blended/hybrid, fully online and face-to-face delivery. Lastly, the competency level question required lecturers to choose between the following levels: entry/basic, adoption, adaptation, appreciation, and innovation. The entry/basic level indicates users’ familiarity with basic LMS digital tools, adoption level which indicates the prerequisite and basic knowledge and understanding of LMS functions. The adaptation level, also known as the higher intermediate level, indicates pre-requisite and basic knowledge and understanding of LMS functions, as well as the ability to integrate digital technologies and resources in learning content. The appreciation level, considered an advanced level, indicates knowledge that comes with extensive experience with how LMSs and digital technologies work, as well as how to utilize them to achieve specific tasks. The innovation level is the highest level focusing on integration and transformation. This is where users look beyond the built-in LMS tools to combine them with external, innovative technologies.

4.2.2. Interview

Semi-structured interviews consisting of four questions were used to gather qualitative data. These interviews allowed participants to provide extensive, free-form answers to open-ended questions in their own words instead of choosing from a pre-made list (Poth, 2023). These kinds of inquiries are essential for qualitative research because they provide insight into the perspectives, experiences, and opinions of participants. Typical examples of the questions asked are as follows: Explain how the delivery method you preferred in 2023 while using the LMS to teach or facilitate learning influenced your students’ engagement? Indicate your experiences of utilizing the LMS? Were there any challenges you encountered while using LMS and other technologies that impact your competency in utilizing the platform? Yes or No. Elaborate.

4.2.3. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using a thematic analysis with the aid of Atlas.ti, allowing us to organize data into insightful patterns and produce new information based on assumptions about the data (Saldaña, 2020). The gender differences in the LMS project were first input into the system. One primary document known as the LMS open-ended interview questionnaire, was published. After the data were uploaded, 44 codes were generated. Following completion, the software produced 109 quotes. The researchers then used the document analysis coding method in Atlas.ti to verify the codes and quotations to check each code’s relevance, meaning, and context to ensure the validity, accuracy, and transparency of the qualitative analysis (Woolf & Silver, 2017). A code hierarchy was then built by the researchers to assist in producing four themes: LMS competency level, experience with LMSs, the mode of delivery, and challenges.

5. Results

5.1. Use of the LMS

In terms of H1 (there is a significant difference between genders and lecturers regarding their competence in the use of LMSs). Gender-related differences in LMS use were examined using Cohen’s d to account for unequal group sizes (64.2% women, 35.8% men). Cohen’s d provides an estimate of the standardized mean difference and is robust against unequal variances between groups (Lakens, 2013; Cohen, 1988). Descriptive statistics indicated that women (M = 1.22, SD = 0.42, n = 78) had slightly higher LMS usage than men (M = 1.19, SD = 0.39, n = 43). However, an independent-samples t-test, shown in Table 2, revealed no statistically significant difference in LMS usage between genders, t (119) = 0.41, p = 0.68. The effect size was small, Cohen’s d = 0.41, 95% CI [−0.29, 0.45], suggesting that the gender difference was minimal and of limited practical importance.

Table 2.

The independent t-test of lecturers’ competence in the use of the LMS use in teaching based on gender.

5.2. Competency Levels in Using the LMS

Regarding H2, there is a significant difference between gender and lecturers regarding competence levels in using digital technologies and the LMS. A chi-square test of independence was conducted. The results shown in Table 3 were not statistically significant, χ2(4, N = 121) = 2.80, p = 0.592, indicating that competency levels do not differ significantly across genders. Although 40% of cells had expected counts below 5, the overall test reveals no meaningful relationship between gender and competence level in using digital technologies and the LMS. Practically, the results indicate that while male and female academics report similar levels of LMS use, slight variations may reflect differences in preferred teaching approaches, such as face-to-face versus blended or online modes.

Table 3.

The chi-square tests of lecturers’ competency levels of using LMSs based on gender.

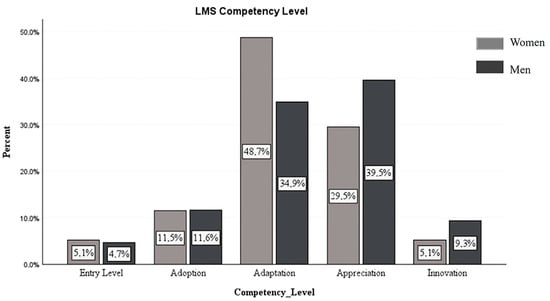

To further analyze these results, a clustered bar chart was constructed, as shown in Figure 1, which highlights that both genders follow a similar distribution, with the majority (83%) of lecturers at the adaptation level, followed by less than three-quarters (69%) of the lecturers at the appreciation level. The results in Figure 1 reveal that women exhibited a stronger leaning toward adaptation. In contrast, men are split more evenly between adaptation and appreciation levels and show a slightly higher percentage in innovation. However, these visual differences are not statistically significant, as confirmed by the chi-square test, p = 0.592, in Table 3.

Figure 1.

The clustered bar chart of lecturers’ competency levels in using the LMS based on gender.

5.3. Mode of Delivery

Relating to H3, there is a significant difference between male and female lecturers’ preferred modes of delivery. Women (M = 2.78, SD = 0.45) reported higher scores than men (M = 2.44, SD = 0.55). This suggests that gender may influence the mode of delivery outcome, with women more likely to have higher-coded (possibly more complex) delivery types. The results in Table 4 indicate that there is a significant difference between male and female lecturers in their preferred mode of delivery, t (72.92) = 3.49, p < 0.001, with a mean difference of 0.34 (95% CI [0.15, 0.54]). The effect size analysis shows that gender has a moderate, statistically significant impact on mode of delivery. Cohen’s d ≈ 0.48 indicates that the average female score is about 0.48 standard deviations higher than the average male score. This suggests that gender plays an influential role in shaping delivery methods. Practically, this means that women tend to use higher-coded or more complex delivery modes compared to men, with a moderate magnitude of difference.

Table 4.

The independent t-test of lecturers’ preferred modes of delivery based on gender.

6. Qualitative Findings

Four themes emerged from the open-ended interview questionnaire on LMSs: the LMS competency level, experience with LMSs, mode of delivery and challenges.

6.1. LMS Competency Levels

In Question 1, lecturers were asked to describe their level of digital competency in LMS use. It was found that lecturers had different competency levels, ranging from entry to basic, adoption, adaptation and innovation. Figure 2 shows the LMS user proficiency level. The basic level, which indicate users’ familiarity with basic LMS digital tools, it is revealed that some lecturers were still learning to incorporate the LMS into their teaching practice and require more training to become competent. Lecturer 7 stated, “I am still learning.” In turn, Lecturer 15 said “I feel I am only able to do the very basics and would really like to do more training on the use of the LMS. The problem is that when training is provided, it always falls within my face-to-face contact time in classes. I cannot afford to take time off from my classes to attend the courses at the times that they are offered.” These findings indicate that many lecturers are still at the entry or basic level of LMS usage, suggesting a significant need for targeted professional development programs at inconvenient times.

Figure 2.

The LMS user proficiency level.

In terms of the adoption level, which indicates the prerequisite and basic knowledge and understanding of LMS functions, some lecturers rated themselves as average, moderate or satisfactory, meaning that they knew how to utilize the system and populate the content. Lecturer 2 postulated, “I have a good idea of how the LMS works,” and lecturer 17 said “I find LMS very easy to use. I can create content and transfer old module content to the new module in the LMS.” However, one of the lecturers indicated some difficulties in manipulating some of the tools and found it hard to navigate the system. Lecturer 10 agreed: “I struggle using some of the tools, populating and navigating the LMS.” These findings suggest that while some lecturers felt confident in using the LMS, others struggled with specific tools. This disparity suggests a need for differentiated training programs that cater to varying levels of competence among lecturers.

The adaptation level, also known as the higher intermediate level, indicates prerequisite and basic knowledge and understanding of LMS functions, as well as the ability to integrate digital technologies and resources in learning content. It was discovered that most of the lecturers were able to use various interactive LMS digital tools and incorporate other technologies and resources to enhance learning and teaching and thus to promote active learning in an online environment. Lecturer 19 stated, “I am skilled in 90% of the tools available on the LMS,” while lecturer 16 mentioned that “Turnitin is a useful tool for preparing our students to know more about plagiarism, which works very well, and I get to use the intelligent agent to track all the high-risk students.” Lecturer 18 stated that “LMS is very good this year. I have explored various students’ interactions tools online. I can post content, links, announcements, do assignments and quizzes as well as populate the marks in the Gradebook.”

The findings reveal that some of the lecturers enjoyed themselves and were motivated and competent in using the LMS features. Lecturer 17 pointed out “I am able to use most of the features on the LMS and enjoy using the platform to organize the work that will be presented to students,” and lecturer 21 declared “I am motivated and skilled to use various teaching technology tools within LMS. I am very eager to experiment with new tools too.” One of the lecturers indicated some challenges with utilizing third-party tools and setting up Gradebook. Lecturer 20 stated the following: “I am skilled, I use quizzes extensively, also rubrics; however, I have some challenges with Turnitin and Gradebook.” Most lecturers reported being competent and skilled in using various interactive LMS tools and integrating additional technologies to enhance learning. This indicates a positive trend towards digital literacy and the effective use of technology in teaching, which can lead to improved student engagement and learning outcomes.

The innovation level, considered an advanced level, indicates knowledge that comes with extensive experience with how LMSs and digital technologies work, as well as how to utilize them to achieve specific tasks. One lecturer felt that the use of the LMS was innovative, as he was able to introduce new or improved ideas to enhance the effectiveness of the module with the application of various digital tools. Lecturer 1 asserted “I used announcements, content creation, online assignments, quizzes, badges, discussions and interactive third-party software for my classes to ensure the usefulness of my modules online.” This suggests that through the innovative use of LMS tools, lecturers are willing to experiment with new ideas. The mention of using various interactive third-party software suggests that lecturers are open to integrating additional resources into their teaching. It is crucial that lecturers have access to these tools, and guidance should be provided on how to incorporate them into the LMS to effectively enhance learning experiences.

6.2. Mode of Delivery

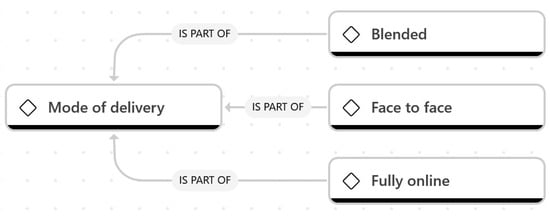

In Question 2, lecturers were asked to explain how their preferred delivery method in 2023 was applied while teaching with the LMS to facilitate learning and influence student engagement. The findings show that lecturers used blended/hybrid, entirely online and face-to-face delivery methods. Figure 3 shows the conceptual network of the mode of delivery. Most lecturers preferred a blended/hybrid approach because, as the institution is undergraduate by nature, students can access the learning material anywhere and anytime. Lecturer 5 posited, “The blended system offers convenience for times when the campus environment is not conducive to teaching and learning. It is easy to engage with students, even when you have other work commitments that make it challenging to meet with them in person. It is easy to arrange special, refresher or catch-up sessions with students on the LMS.” Lecturer 28 stated “I loved using LMS in a blended mode, as it is very easy to ensure that information reaches all students registered for the module anytime,” while lecturer 13 said: “I found the blended or hybrid learning model works well for my modules. Students were required to interact more with the content, and those who complied and made use of all the information made available reaped the rewards”. The findings indicate a strong endorsement of blended/hybrid learning among lecturers, highlighting its convenience, potential to increase student engagement, and adaptability to diverse learning needs.

Figure 3.

The conceptual network of the mode of delivery.

Only one lecturer indicated that they used a fully online delivery mode; Department K was the only department that provided a qualification of this nature. Lecturer 24 mentioned, “One of my modules was fully online because it falls under the fully online programme.” The findings indicate limited engagement in fully online delivery, highlighting the need for UoTs to explore the development of fully online programs and address any barriers that may hinder the adoption of this teaching method.

Some lecturers stated that they used the face-to-face mode because of the nature of the subject and laboratory practical sessions. Lecturer 7 contended “Since the module is a continuous assessment or practical-based, I would say it is fun to engage with the students in the face-to-face mode.” Lecturer 12 stated “My other modules were contact teaching modules.” The findings reveal that lecturers opted for the face-to-face mode due to the large number of students and because some students preferred contact classes to online learning. Lecturer 22 stated that “We have large groups of students, whereby one needs to divide them into groups to be able to have enough working space and equipment. Too many groups affect the completion of the syllabus since we only have almost 14 contact weeks,” and lecturer 7 shared, “The students told me they understand better during contact compared to online.” The findings suggest a strong preference for face-to-face teaching in practical and large-class contexts, highlighting the importance of student engagement, logistical challenges, and the need for effective curriculum design.

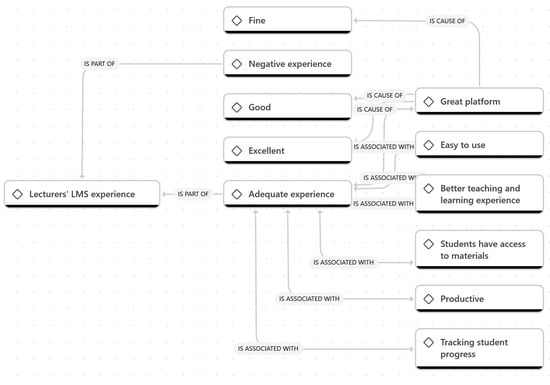

6.3. Experience with the LMS

In Question 3, lecturers were asked to indicate their experience with utilizing the LMS. It was found that most of the lecturers had adequate experience, with only one lecturer admitting a negative experience with using the LMS. Figure 4 depicts the conceptual network of lecturers’ experiences with the LMS. Most lecturers with adequate experience suggest that the LMS is a great platform and is functional and user-friendly. Lecturer 18 stated that “LMS has made teaching and learning very effective as I can reach out to students any time and I can make useful resources available for their perusal.” Lecturer 9 mentioned “2022 was a learning curve, but 2023 was a great experience, and I am hoping to learn and be able to utilize LMS tools to their full advantage,” while lecturer 20 stated that “LMS has been useful in tracking student progress and participation in learning activities.”

Figure 4.

The conceptual network of lecturers’ experiences with the LMS.

It was discovered that most lecturers were satisfied and enjoyed using the various LMS digital tools, as they cultivated interaction among the students and encouraged teaching and learning. Lecturer 4 pointed out “I enjoy the diversity of features available on the LMS and the fact that I can load photos and videos to enhance the students’ experience,” lecturer 11 declared “I use the LMS all the time and find it useful and complementary to my teaching and learning,” and lecturer 23 said that “LMS fosters easy interactions and better teaching and learning experience.”

Only one lecturer had a negative experience using the LMS because they did not attend the regular training that was offered in the Faculty of Science. Even though there had been considerable amount of development, they were not using the LMS in their teaching practice, stating “It can be very frustrating, because I only did the training on the use of the LMS in 2020 and have not worked on it or used it consistently enough. Hence, I find that I have forgotten how to use the various functions, lose a lot of the work due to not saving or doing the wrong thing, and end up frustrated in general because it is time-consuming and sometimes network issues also affect productivity.”

6.4. Challenges Encountered with the LMS and Other Digital Technologies

In Question 4, lecturers were asked to elaborate on the challenges they encountered while using the LMS and other digital technologies that may have impacted their competency in utilizing the platform. Lecturers expressed mixed reactions, as some encountered challenges and others did not, but with most lecturers not facing difficulties using the LMS due to attending faculty and department training sessions. Lecturer 1 indicated, “No, all the tools worked for me,” while lecturer 11 mentioned, “Nope, it was easier to get to know it” and lecturers 21 and 28 stated “No, I attended the training.”

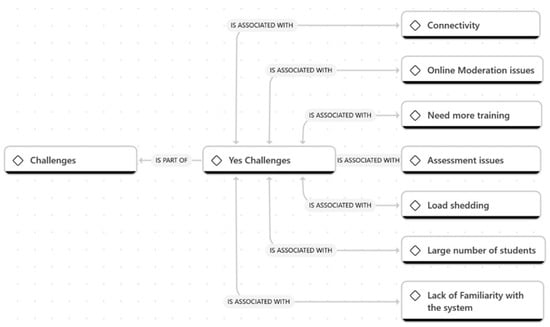

It was discovered that some of the lecturers encountered difficulties that negatively impact their LMS competency. The challenges relate to lack of familiarity with the LMS, the need for more training, connectivity and assessment issues, online moderation, load shedding, and the large number of students. Figure 5 shows the conceptual network of lecturers’ challenges while using the LMS and other technologies, which impact their competency. Some lecturers were not familiar with the LMS because they could not remember how to use the digital tools in the platforms, with lecturer 5 stating “Mainly not remembering how to perform specific functions on the system” and lecturer 20 noting “I find loading audio PowerPoints difficult.” Lecturer 12 answered “Yes, adapting to use some tools.” One lecturer indicated a need for training on advanced tools to attain the adaptation competency level. Lecturer 13 declared, “I still need additional training on advanced tools.” The findings reveal that some lecturers encountered connectivity issues while using LMS. Lecturer 8 stated “Yes, giving assessments/tests is sometimes a challenge due to connectivity problems for some students” and lecturer 11 mentioned a “Poor internet link.” Lecturer 17 postulated that “Having connectivity issues impacts negatively on using LMS.”

Figure 5.

The conceptual network of lecturers’ challenges while using the LMS and other technologies that impact their competency.

Some lecturers lack confidence in utilizing assessment tools. Lecturer 22 mentioned that “I have a challenge of making amendments to Turnitin assignments and the gradebook. I do not want to amend after I have entered/captured quiz marks. I am afraid of losing data or confusing students.” One lecturer with large classes found it easier to communicate online with students but encountered challenges in executing mathematics assessments that require students to show steps to arrive at the solution, pointing out “Yes, having a huge number of students helps in things like communications, but when it comes to working online (giving tests, assignments, and quizzes), it becomes a little bit of a problem for mathematics, since the system favors ‘multiple choice questions’ in terms of auto-marking the questions.” Some lecturers encountered challenges with online proctoring, which is meant to support online moderation, as students cheated and the process of verifying cheating students was tedious. Lecturer 3 noted “I only encountered challenges with the invigilator app where students were copying” and lecturer 22 said, “Checking the invigilator app feedback can also be a tedious job, especially if you have more than 300 students in your class.” One lecturer indicated that students complained about the load shedding schedule in their area, which hindered them from engaging in LMS activities. Lecturer 20 said, “Students complain about load shedding.”

7. Discussion

Regarding H2, all results point to no significant correlation between gender and competency in digital tool and LMS use. Furthermore, in response to research question 1—what LMS digital competency levels do lecturers possess—lecturers stated that their LMS digital competency and proficiency varied from the entry or basic level to adoption, adaption, and innovative levels. The variation in the entry or basic digital competency level among lecturers suggests that there is a digital divide within the Faculty of Science. Some lecturers are more adept at utilizing LMS tools than others, which can impact the overall quality of teaching and learning experiences. Suzer and Koc (2024) indicated that higher education institutions should assess the specific needs of their Faculty of Science and provide tailored support to assist all lecturers attaining a competent digital literacy level.

The adoption level revealed mixed levels of competence among lecturers, reflecting a broader institutional challenge regarding LMS competency levels. Al-qdah et al. (2025) encourage a culture of continuous learning and adaptation to digital LMS tools to ensure that all lecturers are appropriately equipped to effectively integrate technology into their teaching. Regarding the level of lecturers’ adaptation to using LMS digital tools, many lecturers expressed enjoyment and motivation in using the LMS, suggesting that when they felt competent and engaged with the tools, they were more likely to utilize them effectively. This can foster a more dynamic and interactive learning environment, which is beneficial for both lecturers and students (Garutsa, 2025). The innovative use of LMS tools suggests that lecturers were willing to experiment with new ideas. It is crucial to create an environment that fosters experimentation, enabling lecturers to test new methods and tools without fearing negative consequences. Garutsa (2025) opined that fostering the innovative use of LMS tools and advanced technologies can lead to the discovery of effective teaching strategies that benefit students.

Regarding H3, there is a significant difference between male and female lecturers in their preferred mode of delivery. Such a difference highlights the need for institutions to provide tailored support and professional development to ensure that all academics are equally equipped to adopt diverse delivery methods, thereby promoting consistency and inclusivity in student learning experiences. Regarding sub-research question 2—Which delivery method do lecturers prefer while using the LMS? It may be seen from the findings that the predominant preference for a blended/hybrid approach suggests that lecturers recognize the benefits of combining online and face-to-face interactions. This method allows for flexibility and accessibility, which is particularly important in an undergraduate setting where students may have varying schedules and commitments. This finding emphasizes the importance of designing courses that promote interaction and engagement through the LMS. Imran et al. (2023) indicated that the hybrid approach is an effective way to enhance learning outcomes and student satisfaction. Furthermore, Coe et al. (2025) showed that blended teachers reported that asynchronous and blended learning had a beneficial effect on their well-being. Although activities may be planned in time, educators felt that using a blended approach greatly enhanced their work–life balance during term time and that their mental health improved.

The fact that only one lecturer indicated a preference for fully online delivery suggests that this mode of teaching is not generally embraced across departments. This could indicate a lack of fully online programs available in other departments, which may limit the opportunities for students to engage in these learning experiences. The effectiveness of fully online learning is often linked to the level of interaction and feedback provided by lecturers; students value timely and constructive feedback, which can be more challenging to achieve in an online format (Imran et al., 2023).

In the context of face-to-face teaching, it was found that this mode is essential in disciplines where practical skills are essential, because students are more engaged in a physical environment, which enhances their learning experience and facilitates a better understanding of complex concepts. This finding is supported by Imran et al. (2023), who alluded that many students and lecturers still prefer face-to-face teaching due to its advantages in promoting comprehension, developing skills, and fostering a sense of community. It can be observed that students often feel more engaged and supported in traditional classroom settings, which can lead to improved learning outcomes. The challenges related to large student groups are a significant logistical issue in face-to-face teaching. Students should be divided into manageable groups for practical work, as noted in studies that discuss the impact of class size on teaching effectiveness and student engagement.

Regarding H1, it was revealed that gender does not significantly influence lecturers’ competence in the use of the LMS because they must all integrate technologies to enhance teaching and learning. It can be observed that women in this study exhibited slightly higher LMS use than men; however, the difference is so small that it is unlikely to be meaningful or significant in real terms. This implies that, in practice, both genders use the LMS at nearly the same level. However, this difference is minimal and is consistent with prior studies, such as that of Ukaegbu and Zaid (2025), who in a study conducted in Nigeria, showed that gender is not a strong predictor of LMS adoption or engagement. In response to sub-research question 2—How have the lecturers experienced utilizing the LMS?—most lecturers reported positive experiences with the LMS, highlighting its effectiveness in enhancing teaching and learning. This aligns with findings from Almogren (2022), who emphasized that LMS platforms like Canvas and Moodle significantly improve educational outcomes by facilitating real-time information sharing and allowing students to learn at their own pace.

Many lecturers appreciated the user-friendly nature of the LMS and its diverse features, which foster interaction among students. This is supported by Ghilay (2019), who categorized effective LMS features into content management and user management. The findings from our study emphasize the importance of LMSs in innovative education, particularly in enhancing teaching effectiveness and student engagement. The positive experiences reported by lecturers highlight the potential of LMSs to transform educational practices. However, ongoing training and support are essential to ensure that all lecturers, regardless of their experience level or gender, can utilize these systems effectively to their full potential.

A notable portion of lecturers expressed confidence in using the LMS, attributing their ease of use to participation in faculty and departmental training sessions. This finding is consistent with those of Al-Fraihat et al. (2020), who emphasized the importance of professional development in enhancing lecturers’ technological competencies. Conversely, the challenges identified by several lecturers underscore the complexities of integrating technology into teaching practices. Issues such as a lack of familiarity with the LMS, inadequate training, and connectivity problems were prevalent. This aligns with the findings of Dlalisa and Govender (2020), who noted that insufficient training can lead to decreased confidence and increased anxiety among lecturers when using digital tools. The challenges outlined above directly influence lecturers’ competencies in using LMSs. The lack of familiarity and confidence, coupled with inadequate training, can lead to a digital divide among lecturers, with some being more adept at using LMSs than others. This disparity can affect the overall quality of teaching and learning. It has been discovered that some lecturers reported difficulties due to a lack of familiarity with LMSs, which negatively impacted their ability to utilize the platform effectively (Thompson & Harris, 2025). There was a clear indication that many lecturers wanted more training, particularly on the advanced tools within the LMS. This suggests that ongoing professional development is crucial for enhancing competency (Majanja, 2020). Research indicates that targeted training programs can significantly improve lecturers’ confidence and proficiency in using LMSs, ultimately benefiting student engagement and learning outcomes (Simelane-Mnisi & Mokgala-Fleischmann, 2022).

Lecturers noted connectivity problems relating to a poor internet connection, which hindered their ability to conduct assessments and effectively engage with students. This issue not only affects lecturers but also impacts students’ learning experiences (Nguyen-Viet & Nguyen-Viet, 2023). Studies have shown that reliable internet access is essential for the successful implementation of LMSs in educational settings, and thus addressing these connectivity issues is vital for ensuring equitable access to learning resources (Alfayez, 2024). The findings also reveal a lack of confidence among some lecturers in utilizing assessment tools, especially for mathematics assessments. This finding illustrates the limitations of LMS platforms in accommodating diverse assessment types, particularly those requiring complex problem-solving skills (Ukaegbu & Zaid, 2025). The difficulties associated with online proctoring further complicate the assessment landscape. The challenges of maintaining academic integrity in online environments have been widely discussed, with many lecturers expressing concerns about the effectiveness of proctoring tools (Simelane-Mnisi, 2023a). Finally, the issue of load shedding highlights that external factors can impede both lecturers’ and students’ engagement with LMSs. This situation is particularly relevant in regions where power supply is inconsistent, affecting not only access to technology but also the overall learning experience (Simelane-Mnisi, 2023a).

The findings of this study suggest that adopting feminist and transformative pedagogies in online teaching is necessary. By prioritizing inclusivity and critical engagement, lecturers can create learning environments that not only acknowledge but also account for diversity. This shift is essential for fostering a more equitable educational landscape that empowers all lecturers and students to thrive. As articulated by (Jiménez Cortés & Triviño Cabrera, 2023), the importance of reorganizing teacher–student relationships and prioritizing lecturer empowerment in online teaching are emphasized in feminist pedagogy for online learning. Gonzàlez and Conejo (n.d.) highlight the importance of creating inclusive online learning environments that not only accommodate diverse identities but also actively engage lecturers and students in discussions about power dynamics and social justice.

8. Limitations of the Study

This study utilized stratified random sampling to select the participants, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other contexts or populations outside the specific university or lecturers involved. Another limitation is the stratified sampling method, which did not ensure equal gender representation among participants. While the qualitative data were collected through interview questions, the applicability of the insights may be limited by the relatively small number of participants (28 lecturers) who were recruited for this aspect of the study.

9. Conclusions

This study highlights several key findings regarding gender differences in LMS competency and usage among lecturers at a selected UoT in South Africa. In this study, the effect sizes were calculated using stratified sampling not targeting equal gender representation; furthermore, some departments lacked either male or female participants. Despite these limitations, no significant differences in LMS competency were found between male and female lecturers, and both genders demonstrated varying levels of proficiency, with some lecturers still at the entry or basic level, indicating a need for targeted professional development programs. A significant difference was observed in the preferred mode of delivery between genders. Most lecturers favored a blended/hybrid approach, recognizing its benefits for flexibility and accessibility. This preference suggests that lecturers adapt to the needs of students, who may have varied schedules. Most lecturers reported positive experiences with the LMS, appreciating its user-friendly features and the ability to enhance student engagement. Some lecturers reported experiencing challenges, especially those who had not participated in regular training.

The findings highlight the significance of ongoing training and support for all lecturers to ensure that they can utilize LMS tools effectively. This is particularly crucial for those who may feel less confident about their digital competencies. While training can enhance competency and confidence, significant challenges remain for many lecturers, particularly regarding connectivity, assessment, and external disruptions. Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach that includes ongoing professional development, improved infrastructure, and more adaptable assessment tools. Integrating feminist and transformative pedagogies into online teaching practices can significantly enhance the learning environment, making it more inclusive and equitable. By addressing these gender disparities, this research contributes to the broader goal of achieving SDG 5 on gender equity in higher education, ultimately leading to improved student engagement and learning outcomes. By leveraging technology, feminist pedagogy aspires to cultivate inclusive learning environments that empower and respect all participants, enhancing gender equity in educational settings. Future research should aim for a more balanced sample to provide a clearer understanding of gender dynamics in LMS usage and competency among lecturers.

Author Contributions

Title, S.S.-M. and J.M.M.; introduction, S.S.-M.; research question and hypothesis development, S.S.-M.; literature review, S.S.-M.; methods, S.S.-M.; data analysis, S.S.-M.; results, S.S.-M.; discussion, S.S.-M.; data for the tables and figures, S.S.-M.; references, S.S.-M.; project administration and funding acquisition, J.M.M.; data curation, J.M.M.; qualitative findings, J.M.M.; limitations of this study, J.M.M.; and conclusion, J.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a [National Research Funding (NRF) Thuthuka Grant]; grant number [138262].

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Sibongile Simelane-Mnisi and approved by the Tshwane University of Technology Ethics Committee) (REC2020/11/014, 2020/10/ and renewed 2023/07, date of approval: 31 July 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The SECOND author acknowledge financial support from the National Research Funding (NRF) Thuthuka Grant to conduct this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LMS | Learning management system |

| UoT | University of Technology |

References

- Alfayez, A. A. (2024). Effects of internet connection quality and device compatibility on learners’ adoption of MOOCs. Educational Technology & Society, 27(2), 270–283. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48766175 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Al-Fraihat, D., Joy, M., Masa’deh, R., & Sinclair, J. (2020). Evaluating e-learning systems success: An empirical study. Computers in Human Behavior, 102, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almogren, A. S. (2022). Art education lecturers’ intention to continue using the blackboard during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: An empirical investigation into the UTAUT and TAM model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 944335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-qdah, M., Alanezi, S., Alyami, E., & Ababneh, I. (2025). Gender differences in e-learning tool usage among university faculty members in Saudi Arabia post-COVID-19. COVID, 5(5), 71. Available online: www.ej-edu.org (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Bacon-Shone, J. (2022). Introduction to quantitative research methods. The University of Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

- Bakkabulindi, F. (2023). Quantitative data analysis inferential statistics. In C. Okeke, & M. van Wyk (Eds.), Educational research: An African approach (pp. 413–432). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chindomu, R. (2024). Technology practices to promote equity, Access and quality in South African higher education: A multi-case study [Masters thesis, University of the Witwatersrand]. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Coe, J., Millett, A. C., Beane, S., & Grenfell-Essam, R. (2025). Educator experiences of intensive and blended teaching andragogy in UK higher education. Review of Education, 13(3), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2022). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dlalisa, S. F., & Govender, D. W. (2020). Challenges of acceptance and usage of a learning management system amongst academics. International Journal of E-Business and E-Government Studies, 12(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falade, A. A. (2023). Lecturers’ awareness in the use of Edmodo for teaching. Indonesian Journal of Educational Research and Review, 6(1), 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garutsa, T. C. (2025). Exploring gender preferences for collaborative and assessment e-learning tools: A South African perspective. Journal of Education and Learning Technology (JELT), 6(4), 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghilay, Y. (2019). Effectiveness of learning management systems in higher education: Views of lecturers with different levels of activity in LMSs. Journal of Online Higher Education, 3(2), 29–50. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3736748 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Gonzàlez, I. G., & Conejo, M. A. (n.d.). Online teaching with a gender perspective: Guides to mainstreaming gender in university teaching. Xarxa Vive d’univesitats. Available online: https://cdn.vives.org/var/www/html/vives.org/wp-content/blogs.dir/11/files/2024/07/18130650/onlineteaching_eng.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Imran, R., Fatima, A., Salem, I. E., & Allil, K. (2023). Teaching and learning delivery modes in higher education: Looking back to move forward post-COVID-19 era. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoncillo, F. A. (2024). Perceived learning management system effectiveness, teacher’s self-efficacy, and work engagement: Groundwork for an upskilling plan. International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation (IJRSI), XI(III), 560–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Cortés, R., & Triviño Cabrera, L. (2023). Technologies, multimodality and media culture for gender equality: Advancing in digital transformation of education. Dykinson. Available online: https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/5726761 (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Lakens, D. (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubinga, S. N., Maramura, T. C., & Masiya, T. (2023). Adoption of fourth industrial revolution: Challenges in South African higher education institutions. Journal of Culture and Values in Education, 6(2), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumadi, M. W. (2023). The logic of sampling. In C. Okeke, & M. van Wyk (Eds.), Educational research: An African approach (pp. 224–241). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Majanja, M. K. (2020). The status of electronic teaching within South African LIS Education. Library Management, 41(6/7), 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maree, K. (2023). First step in research (3rd ed.). Van Schaik. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Viet, B., & Nguyen-Viet, B. (2023). Enhancing satisfaction among Vietnamese students through gamification: The mediating role of engagement and learning effectiveness. Cogent Education, 10(2), 2265276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhedzi, A., & Azionya, C. M. (2025). The digital activism of marginalized South African gen z in higher education. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Bempah, E., Opoku, D., & Sam-Mensah, R. (2022). Gender differences in e-learning success in a developing country context: A multi-group analysis. European Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 3(4), 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poth, C. N. (2023). The Sage handbook of mixed methods research design. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. (2020). Fundamentals of qualitative data analysis. In M. B. Miles, A. M. Huberman, & J. Saldaña (Eds.), Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (pp. 61–99). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Simelane-Mnisi, S. (2023a, December 6–7). Effectiveness in maintaining academic integrity while using online proctoring for online assessment [Paper presentation]. International Conference on Teaching, Assessment and Learning in the Digital Age (DigiTal2k), Cape Town, South Africa. Available online: https://icdigital.org.za/ (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Simelane-Mnisi, S. (2023b). Effectiveness of LMS digital tools used by the academics to foster students’ engagement. Education Sciences, 13(10), 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simelane-Mnisi, S., & Mokgala-Fleischmann, N. (2022). Training framework to enhance digital skills and pedagogy of chemistry teachers to use IMFUNDO. In E. Babulak (Ed.), New updates in e-learning. IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzer, E., & Koc, M. (2024). Teachers’ digital competency level according to various variables: A study based on the European Digcompedu framework in a large Turkish city. Education Information Technology, 29, 22057–22083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S. S., & Zainal, N. M. (2020). Examining gender differences in LMS usage: A study of lecturers in Malaysian higher education institutions. Asian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(2), 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J., & Harris, O. (2025). A narrative review of educational technology in higher education. Social Science Chronicle, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukaegbu, C., & Zaid, N. M. (2025). The impact of gender and teaching experience on lecturers’ competence in the use of learning management systems in higher education in Nigeria. Innovative Teaching and Learning Journal, 9(1), 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2015). Department of economic and social affairs sustainable development: The 17 goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Van Wyk, M., & Taole, M. (2023). Research design. In C. Okeke, & M. van Wyk (Eds.), Educational research: An African approach (pp. 164–185). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, N. H., & Silver, C. (2017). Qualitative analysis using ATLAS.ti. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yawe, B., & Mubazi, J. (2023). Quantitative data analysis descriptive statistics. In C. Okeke, & M. van Wyk (Eds.), Educational research: An African approach (pp. 164–185). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).