Abstract

The use of Norwegian numerals in the Sámi language is widespread among Sámi native speakers. Like the Sámi languages and the minority language Kven, Welsh is an endangered minority language in a Western European country with one school system. A study from Wales revealed that children who either spoke Welsh only at home or both at home and at school read and compared two-digit numbers more accurately than monolingual English children. Unlike the Norwegian and English languages, the Sámi, Kven, and Welsh languages have strictly regular counting systems. Analyses of the counting systems for the numerals 11–20 in eight Sámi languages and Kven and comparisons with the counting system in Standard Welsh have resulted in a categorization of the counting systems into three groups regarding transparency and possible support for children’s grouping of ten ‘ones’ into one ‘ten’. The analysis gives reason to believe that reversing the increased use of Sámi and Kven numerals may contribute to Sámi and Kven children’s grasping of the base-10 system because of the counting systems’ transparency. Understanding the base-10 system is fundamental for further learning in school mathematics. Based on the findings, we recommend that Sámi and Kven numerals be included in the mathematics curriculum.

1. Introduction

The Sámi are an Indigenous people of the Arctic who inhabit Northern Scandinavia and the Kola peninsula of Russia. As part of the Norwegian government’s assimilation policies (the Norwegianization policies), Norwegian has largely replaced the Sámi language. The use of Norwegian numerals in the daily Sámi language is and has been widespread. Nesheim (1952) documented how Norwegian replaced Sámi in daily communication in the Lyngen area in Northern Norway, in the years just after World War II. He found that Sámi numerals from 11 and upwards were more or less consequently replaced by Norwegian numerals in people’s everyday Sámi language. A more recent study (Dannemark, 2014) documents a widespread use of Norwegian numerals in everyday Sámi language in Guovdageaidnu/Kautokeino, despite the fact that North Sámi is this municipality’s official language. Antonsen (2021) documents a widespread use of Norwegian numerals in the Sámi language in the North Sámi language area.

Norway’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) report (Høybråten et al., 2023) documents that a major part of the Sámi and Kven populations have lost their mother tongue. The report points out that “a central part of the reconciliation process is to reverse the language consequences of the Norwegianization policies” (p. 654, author’s translation). The Commission suggests a targeted investment in the Sámi and Kven languages. This paper argues for one such targeted investment: to reverse the development toward using Norwegian numerals in daily Sámi language and Sámi mathematics education. We also explain why we suggest that Sámi children should learn to count to twenty in more than one Sámi language, even though they are second- or third-language learners of Sámi.

To understand the structure of the base-10 numeration system, you must be able to group ten ‘ones’ into a unit of one ‘ten’, and to understand ‘ten’ as both ten ‘ones’ and one ‘ten’ simultaneously (Thanheiser & Melhuish, 2018). In some languages, the numerals from eleven to twenty are created according to a systematic structure that can support the child’s understanding of the base-10 numeration system. We argue why this is the case for the Sámi and Kven languages. By contrast, the structure of 11 and 12 in Norwegian (and English and Swedish) differs from the structure of 13–19. In addition, 20 appears as a new numeral rather than as ‘two ten’ in Norwegian. Therefore, our research question is: How can the use of Sámi and Kven numerals support children’s understanding of the base-10 numeration system?

Sámi and Kven are endangered minority languages in a Western European country with one school system. This is the case for Welsh, too. Dowker et al. (2008) studied Welsh children. The children in their study lived in Wales and were enrolled in the Welsh school system. This represents a major difference from comparative studies of children living on different continents, with different cultures and different curricula. Dowker et al. (2008) revealed that even though Welsh numerals are longer than the English ones, Welsh-speaking children outperform English-speaking children in reading and comparing two-digit numbers.

Unlike English, Welsh numerals for 11–19 follow a strictly regular structure, which is a suggested reason why Welsh-speaking children perform better at using the principles of place value. Sámi numerals 11–20 follow a logical structure that should intuitively be easier to grasp than the Norwegian counting system (Fyhn et al., 2024). However, the North Sámi numerals are longer than their Norwegian and Swedish counterparts. This is a widespread explanation for why many native North Sámi speakers prefer to use Norwegian and Swedish numerals. The similarities with the Welsh language situation give reason to believe that the findings of Dowker et al. (2008) may be applicable in Scandinavia.

To shed light on the research question, we answer two sub-questions: (a) What are the structures of the Sámi and Kven counting systems? and (b) how do Sámi and Kven counting systems appear compared to the Standard Welsh system? We present an overview of the current situation for Sámi languages and education, followed by a literature review on the counting systems in Norwegian and Swedish, in some Finno-Ugric languages, and in Welsh. The data in our study consist of a list of counting systems for 1–20 in: (a) the six Sámi languages that are spoken in Norway, (b) Kven, and (c) Kildin Sámi and Inari Sámi, which are spoken in regions close to Norway. We will identify similarities and differences in the counting systems of the Sámi and Kven languages before comparing them with Welsh counting systems. Based on the analysis of the two sub-questions, we discuss how Sámi and Kven children’s use of numerals might influence their understanding of the base-10 system. Knowledge about the possible benefits of using Sámi and Kven numerals is one way to reverse the linguistic consequences of the Norwegianization policies.

1.1. Sámi Languages and Education in Norway

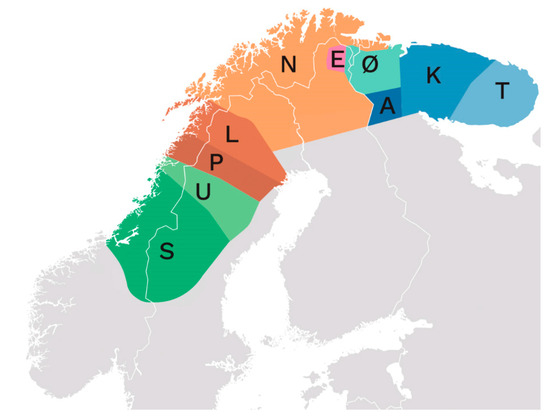

The Sámi are a heterogeneous group of people. In total, ten Sámi languages are still alive (Knutsen-Duolljá et al., 2024), as shown in Figure 1. The North Sámi (N), Lule Sámi (L), and South Sámi (S) languages are recognized as official languages in Norway. Pite Sámi and Ume Sámi are spoken in Norway and Sweden. Ter Sámi, Akkala Sámi, and Kildin Sámi are only spoken in Russia, while Inari Sámi (Norwegian: Enare Sámi) is only spoken in Finland. Skolt Sámi (also named Østsamisk in Norwegian) is mainly spoken in Finland. The Kven people are a national minority in Norway (Theil, 2024). The Kven language is mainly spoken within the same area as North Sámi. Sámi and Kven languages belong to the Finno-Ugric language group (Menninger, 1958/1969), while Norwegian (and Swedish and English) are Germanic languages.

Figure 1.

Areas of the Sámi languages. Each area is marked by the language’s first letter in Norwegian. Retrieved from snl.no/samisk License CC BY NC SA 3.0.

The Sámi University of Applied Sciences) opened publicly in 1989, as the first Sámi higher education institution (Sámi Allaskuvla, 2024). The institution is located in Guovdageaidnu/Kautokeino, Norway, close to the Finnish and Swedish borders. The institution educates Sámi teachers for Sápmi (the area inhabited by Sámi people), not just for people who live in Norway. The institution aims to contribute to the strengthening and development of Sámi languages and culture, and because the authors of this article are mathematics teacher educators at SUAS, this is our concern.

1.1.1. The Current Situation of Sámi Languages

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, UNESCO, all Sámi languages are categorized as endangered (Salminen, 2010). The schools have played an essential role in the Norwegian state’s assimilation policies (Høybråten et al., 2023). These policies have massive consequences to this day, as many Sámi and Kven students receive most of their education in the Norwegian language. The TRC report (Høybråten et al., 2023) recommends that Norway develop a program to strengthen the three languages, Pite-, Ume-, and Skolt Sámi. Strengthening the use of Sámi and Kven numerals is one example of reversing the Norwegianization policies. In November 2024, the Norwegian Parliament officially apologized for the earlier Norwegianization policies and injustices, and decided to follow up on some of the Commission’s recommendations, such as strengthening of Sámi and Kven languages (Mortensen Krane, 2024).

In 1987, Norway established a Sámi Act, which includes a Language Act (Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development, 2007). Despite strengthened rights in the field of Sámi education, Sámi students and their families continue to face challenges in terms of Sámi language learning (Broderstad, 2022). There is a lack of teaching material and a shortage of Sámi teachers, among other issues.

1.1.2. The Current Situation of Sámi Mathematics Education

It is well-documented that children benefit from learning mathematics in their first language, both cognitively and for the development of their identity as members of a cultural group (Edmonds-Wathen et al., 2019). A large part of the Sámi population has learned mathematics in the national majority language at school, with both the education and the textbooks being in a language other than their mother tongue (Helander, 2012). Consequently, the language is an additional obstacle for a considerable part of the native Sámi speakers regarding mathematics education. Helander describes how this linguistic situation has resulted in many Sámi language speakers using the majority language instead of their Indigenous language to say their phone number or to read prices at the store.

Jannok Nutti (2013) found a gap between Sámi teachers’ desire to prepare their students for further education in the national school system and their desire to provide them with specific Sámi culture-based knowledge. She describes a tension between teachers’ and parents’ desires for Sámi students to grow up with a strong cultural identity and, at the same time, for them to succeed in school and later have the possibility of obtaining well-paid jobs. This is similar to findings by Meaney (2003): Māori parents and teachers wanted their students to grow up with a strong Māori background and, at the same time, for them to succeed academically in mainstream society, thus allowing them access to high-status and well-paid jobs. Our study intends to contribute to reducing the gap between parents’ and teachers’ aims regarding students’ future mathematics education and their aims for students’ development of cultural identity. Our study intends to explain why an increased use of Sámi numerals by parents, teachers, and students might support the students’ understanding of the base-10 system, which is crucial for understanding further school mathematics.

Sámi curricula exist for most school subjects. On assignment from the Sámi parliament, Fyhn et al. (2024) argue why there is a need for a Sámi mathematics curriculum. In 2025, the Sámi parliament started the process of creating a parallel and equal Sámi mathematics curriculum, and a curriculum text was established as a regulation by the Sámi parliament in October 2025 (Sámediggi, 2025). Our study aims to contribute to the creation of this curriculum by providing an explanation of how the use of Sámi numerals may support children’s learning.

1.2. Revitalization, Reversing, and Regeneration of Language

The TRC report (Høybråten et al., 2023) points to reversing the language consequences of the Norwegianization policies, and the Commission also points to revitalization of languages. Revitalization initiatives in Indigenous languages include education, broadcasting, publishing, and community-based programs (Smith, 2012). Today, processes have been implemented to revitalize the Kven and Sámi languages. The education sector plays an important role, as several children cannot learn Sámi at home.

… Northern Sami and, to some extent, Kven and Lule and Southern Sami language communities, are gaining new language users. The investigation conducted by the [Truth and Reconciliation] Commission shows that revitalisation initiatives are not working satisfactorily and that the languages lack an adequate framework and resources. The Sami parliament and the Sami and Kven organisations and institutions have significantly higher ambitions for language revitalisation than the Norwegian authorities.(Høybråten et al., 2023, p. 88)

Hohepa (2006) points out differences between revitalization, reversing, and regeneration of language; because our cultures are developing, our languages are constantly growing and developing. This might cause challenges for the revitalization of language. To her, ‘language revitalization’ as well as ‘language reversing’ do not reflect enough of a sense of development and growth. She introduced the term ‘regeneration of language’ to characterize the return and regrowth of a language.

Among Sámi speakers, there is still a considerable part of the population that uses Sámi numerals, but there is a need to stop and reverse the increased use of Norwegian numerals. Therefore, we find it most appropriate to use the term ‘language reversing’ in this study.

1.3. Investigating and Representing Numerals in Multiple Languages

Our study analyzes numerals in several different languages. To present numerals (and other words) in languages that are not English, non-English words are written in italics, while English translations are presented in single quotes. For example, the North Sámi numeral čieža is translated as ‘seven’. The numerals 11–19 in Welsh, Sámi, and Kven languages are compound words, so to represent numerals in these languages, we use an interlinear morphemic gloss, as explained by Edmonds-Wathen (2019). A morpheme is the smallest part of a word that carries meaning. For example, the North Sámi numeral čiežanuppelohkái is ‘seventeen’ in English. To present the structure of this compound word, we separate each morpheme with a hyphen; čieža-nuppe-lohkái is translated into ‘seven-second-ten’. The interlinear representation is used to show how grammar reveals the meaning.

| (1) | čiežanuppelohkái | ||

| čieža- | nuppe- | lohkái | |

| ‘seven’- | ‘the second’CG- | ‘ten’ILL | |

| ‘seven toward the second ten’ | |||

In example (1), the top level shows the numeral. The second level shows the numeral’s morphemes, word parts, separated by a hyphen. The third level shows the English morphemic gloss, using CG for consonant gradation, and ILL for illative case. When a North Sámi word is conjugated, declined, or derived, consonant alternation often occurs in the word’s middle consonants. This is similar to the English alternation in “wife”—“wives”, but much more regular and productive (Oahpa!, 2025a). The double b in nubbi, ‘second’, turns into a double p in the morpheme -nuppe in the North Sámi compound numerals 11−19. Furthermore, in Sámi languages, the illative case is used to indicate motion to or into something (Oahpa!, 2025b). The fourth level shows a semi-literal phrasal translation of the numeral. The reason for using morphemic gloss is to provide the readers with further information about the numerals’ structures beyond just idiomatic translation. This is important since we want our study to be accessible to readers regardless of their familiarity with the specific threatened minority languages.

1.4. Counting Systems in Different Languages

Several studies have been carried out on the world’s many counting systems (Pinxten, 2016). About one-sixth of the world’s spoken languages are within the borders of Papua New Guinea (Owen et al., 2018), where different counting systems are used for different purposes. The most frequently occurring systems are those with bases of two, five, ten, and twenty. The Yup’ik people in Alaska use a base-20 and sub-base-5 system that is derived from body terms and spatial terms (Lipka, 2024). This has similarities with some of the counting systems in Papua New Guinea. However, this paper’s focus is on languages with base-10 counting systems.

After an introduction to languages with base-10 counting systems, we provide a more thorough presentation of counting systems that are relevant to this paper’s focus: the Norwegian and Swedish system, the Finno-Ugric systems, and the Welsh systems. We also discuss the possible educational implications of using these counting systems.

1.4.1. Languages with Base-10 Counting Systems

- Grouping by tens is a feature of many languages. For instance, the Swahili counting system from 11–19 is strictly regular (Zaslavsky, 1996). This is also the case for the Indigenous Mapuche numeral system (A. Huencho & E. Chandia, personal communication, 5 September 2025). However, our study focuses on the Sámi and Kven counting systems and comparisons with the Welsh base-10 counting systems, because these can be related to research about Western European minority students’ understanding of the base-10 system.

Children in Japan, China, and Korea tend to perform particularly well in arithmetic on international tests (Mullis et al., 1998; Mullis et al., 2020). Educational methods and different language structures are two possible reasons for this. One cultural characteristic that could explain this is the way in which numbers and arithmetical relationships are expressed in a language. Miller and Stiegler (1987) compared the developmental course of counting in English and Chinese. They found that counting in the “teens” in English poses a particular stumbling block for American children. This aligns with Edgeworth’s more than 200-year-old claim from 1789, referred to by Dowker et al. (2008), that the relatively irregular English counting system may cause a learning disadvantage for English speakers compared with speakers of languages with more regular counting systems.

1.4.2. The Norwegian and Swedish Counting System

The numerals in Norwegian and Swedish are closely related to those in English. The Norwegian numeral ‘ti’ (Swedish: ‘tio’) is ‘ten’ in English, and the Norwegian ‘tjue’ (Swedish: ‘tjugo’) is ‘twenty’ in English. A Norwegian interpretation of the English word ‘twenty’ is ‘tvenne ti’ [tve`n:ə ti:], two ‘ten’; ‘tvenne’ is an old Norwegian form of ‘two’ (NAOB, 2024). It is far from obvious for young learners that ‘twenty’ is an old form of ‘two ten’. Similarly, the Norwegian ‘tjue’ and the Swedish ‘tjugo’ developed from Old Norse forms of ‘two ten’ (NAOB, 2025). Miller and Stiegler (1987) point to another obstacle for English-speaking children: the English language forms number names in the “teens” differently than it does in other decades. Number names in the range 20–99 are formed by suffixing a decade name with a unit value, while the numerals 13–19 are formed by a single digit followed by a word for ‘ten’. We see that the same applies to the Norwegian and Swedish languages.

1.4.3. The Finno-Ugric Systems of Counting

Finnish and Hungarian are the largest languages in the Finno-Ugric family (Menninger, 1958/1969). The Sámi and Kven languages belong to this language group. In Russia, the Mordvins are among the largest Finno-Ugric peoples. The Finno-Ugric counting systems are base-10 systems where all numerals 11–19 follow a consistent structure. The North Sámi word for 10 is logi, while logut means ‘numbers’. The Finnish and Kven word for 10, kymmenen, is similar to the Mordvinian kemein, whereas Hungarian borrowed the Indo-Iranian tiz (Syrian das) for 10.

Table 1 provides some examples of the logical construction of the numerals 10–20. Finnish and Hungarian structure the numerals 11–19 differently; while 11 in Finnish means ‘one-second’ [one of the second 10], the Hungarian 11 is just ‘ten-and-one’.

Table 1.

Finnish and Hungarian numerals. The Finnish word ‘toista’ means second (Menninger, 1958/1969, 113).

Regarding education, Aunio et al. (2006a) translated a Dutch numeracy test and used it on 1029 Finnish children aged 4–8. They found that children in families with more than one child scored higher than children without siblings, and that children from rural areas scored higher than children from urban areas. They found no reasonable explanations for these differences.

Aunio et al. (2006b) state that several studies have shown that young Chinese children consistently outperform their Western peers in abstract and object counting, concrete and mental addition and subtraction, and in the use of sophisticated strategies in mathematical problem-solving. This led them to examine the influence of nationality and age on young Finnish and Chinese children’s number sense. The Chinese children outperformed the Finnish children in counting skills; the researchers explained this as a product of culture and language. One reason for this difference is that the Chinese participants were from two urban schools. Since most Chinese children in rural areas do not attend preschool, and urban children mainly go to preschool from the age of four, these Chinese test results are most likely not representative of Chinese children. The participants were chosen from primary and pre-schools that had already been collaborating with university or academy researchers. We conclude that it is hard to find studies about how the Finnish counting system influences children’s understanding of the base-10 system.

1.4.4. The Welsh Systems of Counting

Cymraeg, the Welsh language, is under threat of extinction due to centuries of political and social pressures from the English (Thomas & Gathercole, 2003). Despite the ongoing revitalization process of the Welsh language, many people living in Wales are prepared for the imminent death of the language. The Education Act of 1988 made Welsh a compulsory subject in all secondary schools in Wales, and since 1996, all primary school children have been required to learn Welsh at school.

Wales uses two different counting systems in school mathematics, based on the Welsh and English languages (Dowker et al., 2008). In addition, there is a vigesimal (base-20) format, which is not used in school mathematics. In Standard Welsh, each number word is easily constructed by knowing the numbers 1–10 and the rule for combining them. Table 2 presents the first twenty Standard Welsh numerals, based on information from the Welsh speakers Isobel Ruby, George Lynch, and Bedwyr Hughes (Personal communication, 21 March 2025).

Table 2.

The Standard Welsh counting system with direct translations to English.

There are masculine and feminine forms of some numbers in the vigesimal format (BBC Cymru Wales, 2002). Their use depends on the gender of the noun to which they refer. When a number is feminine, like for instance dau (two), the number that follows will be in soft form grammatically. In the soft form, d turns into dd, and p turns into b. This is the reason for the double d in Standard Welsh 20, dau ddeg (Isobel Ruby, personal communication, 23 June 2025).

Standard Welsh is more common in the south. It is used in school mathematics, most likely to avoid confusion. It is also easier for beginners to understand. Welsh grammar explains that the Standard Welsh numerals 11–19 are rhythmic and repetitive; the first two syllables are un deg (‘one ten’), and except for fourteen, all of them have three syllables. The vigesimal format is a more formal way of speaking, where numbers are counted in fives. This format is used for expressing dates.

Wales provides a unique opportunity for research on linguistic influences on mathematics, because languages with both regular and irregular counting systems are used at the same time, even within the same schools. Dowker et al. (2008) studied Welsh children from schools in predominantly middle-class social areas; the schools were similar in their social-class intake. The researchers categorized the children into three groups:

- Children whose first language is Welsh, who have a Welsh home environment and who receive Welsh-language schooling;

- Children who receive Welsh-language schooling but have English-speaking parents, an English-speaking home environment, and English as their first language;

- Children whose first language is English and who receive an English-medium education.

The Welsh numerals are longer than their English counterparts. The Welsh numerals 11–19 mainly have three syllables. This means that any advantage of the Welsh counting system over the English one will most likely be due to its regularity and not due to word length. Dowker et al.’s (2008) study revealed that Welsh-speaking children find it easier than English-speaking children to read and compare two-digit numbers, suggesting that they are better at using the principles of place value.

Dowker et al.’s (2008) study supports the idea that a regular counting system will make it easier for young children to count to higher numbers at an earlier stage than a more irregular counting system. This might give students with a regular counting system a head start in manipulating numbers. They further suggest that the concept of ‘place value’ (representation of the base-10 system using written symbols) could be easier to grasp for those who use a regular counting system.

2. Materials and Methods of Analysis

It is not easy to get an insightful overview of the different Sámi counting systems. Speakers of endangered languages have more serious issues to consider than answering questions from researchers they do not know or relate to. The second author is a native speaker of North Sámi with a university-level education in the Sámi language. She has gained a large Sámi network from previous work in the fields of culture and politics. Her language knowledge, in addition to her contacts with speakers of other Sámi languages, is a valuable and crucial resource for our study. There is a need for knowledge of Sámi languages and grammar to understand the words in the dictionaries. The first author has some knowledge of the North Sámi language, but she is not fluent. This means she, to a limited extent, can participate in direct contact with speakers of endangered languages, which is an important part of the data collection. The TRC report (Høybråten et al., 2023) shows numerous examples that have given the Sámi population reasons not to trust Norwegian authorities. This makes it easier for a Sámi-speaking researcher to gain access to networks and build trust. Information about the Lule Sámi counting system was obtained through direct contact with individuals at Sáme Giellagálldo. Katarina Barruk, who is a native speaker of Ume Sámi, provided information about the Ume Sámi counting system.

According to Salminen (2010), North Sámi is the least endangered Sámi language. Around 90 percent of all Sámi speakers use North Sámi (Knutsen-Duolljá et al., 2024). Ter Sámi and Akkala Sámi are almost extinct or extinct and not included in our study. All Sámi languages are undergoing revitalization efforts, but the situation remains demanding

- North Sámi (davvisámegiella) is definitely endangered;

- Lule Sámi (julevsámegiella) is severely endangered in Norway and Sweden;

- South Sámi (åarjelsaemiengïele) is severely endangered in Norway and Sweden;

- Inari Sámi (anarâškielâ) is severely endangered in Finland;

- Pite Sámi (bidumsámegiella) is critically endangered in Norway and Sweden;

- Ume Sámi (ubmejesámiengiälla) is critically endangered in Sweden and extinct in Norway;

- Skolt Sámi (sääʹmǩiõll) is severely endangered in Finland and almost extinct in Norway and Russia;

- Kildin Sámi (кӣллт cāмь кӣлл/kiillt saamʹ kiill) is severely endangered in Russia;

- Ter Sámi (cāмькӣллis/saa’mekiill) is almost extinct in Russia;

- Akkala Sámi is almost extinct or extinct in Russia.

The counting systems of South, Lule, North-, Skolt, Kildin, and Inari Sámi are accessible through Giellatekno’s (2024) Sámi number generator. Pite and Ume Sámi numerals can be found in the Pite Sámi (Sállto, 2023) and Ume Sámi (Sámediggi, 2017) online dictionaries, respectively. The Kven counting system is available through the online Kven grammar (Söderholm, 2017). The intention behind providing an overview of these numerals is to support Sámi teacher education, which means it can help reverse the ongoing process of increased use of Norwegian numerals among Sámi speakers.

2.1. Sámi Counting Systems

Because the Sámi languages are endangered, we include every numeral 1–20 in these eight languages. The Sámi languages follow three different counting systems. The South and Ume Sámi languages, see Table 3, are spoken in the geographically southernmost Sámi areas, marked as S and P in Figure 1. The structure of the numerals 11−19 is transparent and systematic: luhkie-akte: “ten-one”, luhkie-göökte: “ten-two”, et cetera. Twenty is ‘two-ten’ in South and Ume Sámi.

Table 3.

The South and Ume Sámi numerals 1–20.

Lule and Pite Sámi language areas (L and P, respectively, in Figure 1) are geographically located between the northern and the southernmost Sámi language areas. Table 4 presents numerals in these languages. The Lule Sámi counting system has much in common with the counting systems in Table 3, but there is one grammatical difference. Example (2) shows an interlinear representation of lågenanniellja, ‘fourteen’.

| (2) | lågenanniellja | |

| lågenan- | niellja | |

| ‘ten’-LOC | ‘four’ | |

| ‘upon ten, four’ | ||

Table 4.

The Lule and Pite Sámi numerals 1–20.

The top level shows the numeral. The second level shows the numeral’s morphemes, separated by a hyphen. The third level shows the English morphemic gloss, using LOC for locative case. The locative case is used in Sámi languages to indicate the notions in/at or from a place (Oahpa!, 2025c). The fourth level shows a semi-literal phrasal translation of the numeral. The numerals 11 and 12 are: lågenan-akta: ‘upon-ten one’, lågenan-guokta: ‘upon-ten two’.

The Pite Sámi numerals follow two different structures (Sjaggo, 2015). The Pite Sámi I numerals follow a system that we have not found explained grammatically, but it appears similar to the South and Ume Sámi system. However, the Pite Sámi and Lule Sámi languages are closely related, and the Pite Sámi morpheme -låk- is not far from the Lule Sámi låhke, which means ‘ten’. The structure, then, is akkta-låk-akkta, meaning ‘one-ten-one’, and akkta-låk-guäkkte meaning ‘one-ten-two’. The second morpheme in the Pite Sámi II counting system is -lågenan, which is identical to the locative case of the Lule Sámi numeral låhke, ‘ten’. The Pite Sámi II numerals 11−19 are then translated: akkta-lågenan is ‘one-upon-ten’, guäkkte-lågenan is ‘two-upon-ten’. This has much in common with the Lule Sámi system; the only difference is the word order. The Pite Sámi II word order, as seen in akkta-lågenan, is also found in oral Lule Sámi, but mainly among elderly speakers (Svenn-Egil Knutsen Duolljá, personal communication, 22 January 2025). Twenty is guäkkte-lågev; ‘two-ten’ in both systems.

Table 5 presents the counting system of Sámi languages that are spoken in the geographically northern areas. The main areas of these languages are labelled N, E, Ø, and K, respectively, in Figure 1.

Table 5.

The numerals 1–20 in four Sámi languages in the geographically northern areas.

Twenty is ‘two ten’ in these four languages. The Skolt Sámi morpheme -lo is a short form of lååi, ‘ten’, because the letters o and å in these words are pronounced the same way. The North Sámi numeral logi is pronounced [l’åi]. All numerals 11–19 here focus on ‘the second ten’. We show 11 and 12 in North Sámi as examples, similarly to what was explained in example (1): Okta-nuppe-lohkái: ‘one toward the second ten’, guokte-nuppe-lohkái: ‘two toward the second ten’. Nickel (1994) explains the -nuppelohkái part of the North Sámi numerals as ‘being on the way to the next ten’. Karlsen and Somby (2023) present counting from one to twenty in the dialects of Kárášjohka/Karasjok and Guovdageaidnu/Kautokeino. In daily speech, the -nuppelohkái part of the numerals 11–19 is shortened to -nuppelot. This vowel loss, called apocope (Simonsen, 2025), is also found in the Inari Sámi numeral 20, where the final vowel of kyehti, ‘two’, as well as of love, ‘ten’, are missing.

Because the Kildin Sámi language area is located in Russia, the language is expressed using the Cyrillic alphabet. The structure of the numerals 11–19 can be explained using 11 as an example: э̄xxт-эмп-лoaгкь means ‘one-second-ten’. The Inari Sámi numerals follow the same grammatical structure as North Sámi. However, each numeral is consistently shortened similarly to -nuppelot in daily North Sámi speech. The Inari Sámi numeral love, ‘ten’, has two syllables, while -lov, the final morpheme of the numerals 11–19, has only one syllable. This loss of the final vowel, apocope (Simonsen, 2025), also appears in the Skolt and Kildin Sámi numerals 1–9. Nelson and Toivonen (2000) present the Inari Sámi numerals 11 and 12, where there is apocope in the first morpheme; okt-nubá-loh, kyeht-nubá-loh. The Skolt Sámi numerals 11−19 are shortened even further than just apocope. Table 6 shows how the two final morphemes of the numerals 11–19 appear in North, Inari, and Skolt Sámi.

Table 6.

Variations of ‘toward the second ten’ in three Sámi languages.

2.2. The Kven Counting System

In 2005, the Norwegian government submitted a motion for Kven to be recognized as a language and not as a Finnish dialect (Theil, 2024), and Kven was granted minority language status. However, some researchers still claim that Kven is a Finnish dialect (Salminen, 2010). Table 7 shows the Kven numerals, which follow a structure that has much in common with the languages in Table 5. The numerals 11–19 are formed by combining the numerals 1–9 with the morpheme -toista, which is the partitive case of toinen, ‘second’. The partitive case denotes an indefinite part of a whole (Nilstun, 2025).

Table 7.

The Kven numerals 1–20.

Quencasten (2023) provides more insight into dialect variations and pronunciation. The second morpheme of kaksi-kymmentä, ‘two-ten’, is the partitive case of ‘ten’. Thus, like in the Sámi languages, the word for twenty in Kven is ‘two-ten’.

2.3. Analysis

The counting systems in the nine languages are categorized by how the numerals 11–19 are constructed. We distinguish between whether a number is constructed as ‘a one-digit number built upon ten’ or ‘a one-digit number that is approaching twenty’. We also examine whether twenty is created as ‘two ten’ or represented by a new word like the Hungarian búsz. ‘Another issue is whether grammatical cases or consonant gradation are included, or whether numbers are simply listed, as in Standard Welsh, where twelve is un deg dau, which directly translates to ‘one ten two’. The next step in the analysis is to compare these categories of Sámi and Kven languages with the Standard Welsh system.

3. Results

The analysis first organizes the eight Sámi languages and Kven into four different categories, depending on the structure of the numerals 11–19. Next, we compare these categories and the expressions for ‘twenty’ with the Standard Welsh counting system.

3.1. The Structures of Sámi and Kven Numerals

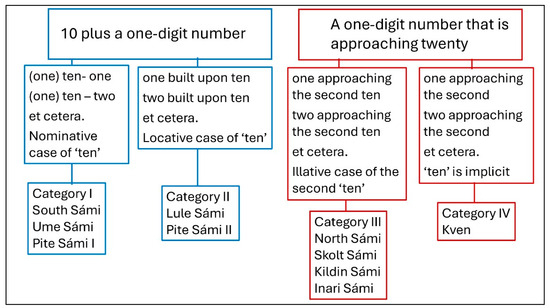

We organize the counting systems of the nine languages into two main categories, each of which is subdivided into two subcategories. In Categories I and II, the numerals 11–19 are structured as ‘ten’ followed by a one-digit number. While the numerals in Category I are formed as ‘ten-one’, ‘ten-two’, et cetera, the Category II numerals are constructed by a one-digit number built upon ‘ten’. In Categories III and IV, the numerals 11–19 are constructed as a one-digit number approaching twenty. Category IV differs from Category III by an implicit appearance of the final morpheme. All nine languages create the numeral twenty as ‘two-ten’. Figure 2 shows the structures of the four categories, described in words. The word for ‘ten’ appears in the nominative case only in Category I, while ‘ten’ is implicit or invisible in Category IV.

Figure 2.

The structure of the numerals 11–19 in the four categories.

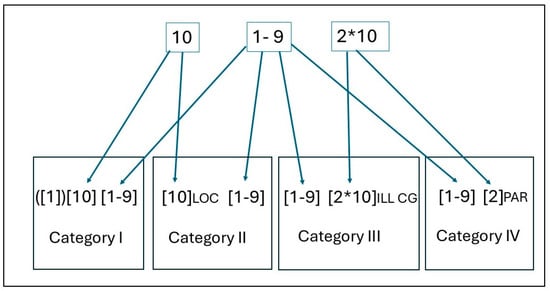

Category I: This includes South and Ume Sámi as well as the Pite Sámi I language. Here, each number is constructed as ‘ten’ or ‘one ten’, followed by a one-digit number. Category II: This includes the Lule Sámi and the Pite Sámi II numerals. Here, the word ‘ten’ changes case from nominative to locative. Category III: The North, Skolt, Kildin, and Inari Sámi counting systems include an explicit reference to ‘the second ten’; -nuppe-lohkái is a combination of nubbeCG and logiILL, where nubbe means ‘second’ and logi means ‘ten’. The shortened forms of -nuppe-lohkái in Inari Sámi: -nubá-loh, and in Skolt Sámi: -m-lo, could form a subcategory, but these forms are similar to the North Sámi short form -nuppe-lot, which is common in daily North Sámi speech. The Inari and Skolt Sámi numerals 11−19 are shortened so the full words are implicit. Category IV: The Kven language has a similar structure, -toista is -toinenPAR, which is the partitive case of ‘second’. This indicates that it is part of something, so the second ‘ten’ is referenced implicitly. The structures of the counting systems are represented using number symbols in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Creation of the numerals 11–19 in the four categories. The letters CG mean Consonant Gradation, while LOC, ILL, and PAR refer to the cases locative, illative, and partitive, respectively.

3.2. Comparisons with the Standard Welsh Counting System

In Standard Welsh, twenty is dau ddeg, ‘two ten’, which is similar to all four categories of Sámi and Kven counting. However, the Kven word for ‘ten’ is in the partitive case, and the Skolt and Inari Sámi languages have apocope (Simonsen, 2025).

For the numerals 11−19, Standard Welsh counting is highly comparable to Category I, which includes the South, Ume, and Pite Sámi I systems. There is one difference: opposed to South and Lule Sámi, the Welsh and Pite Sámi I counting systems include the number ‘one’ before ‘ten’. Category II, Lule and Pite Sámi II, is quite similar to the Standard Welsh counting system. The only difference is that the word ‘ten’ is in locative case, as shown in Figure 3. Thus, the structure of the Standard Welsh counting system lies somewhere between Category I and Category II.

Categories III and IV differ more from the Welsh system. The Category III counting system focuses on the move toward the second ten. This dynamic shift toward the second ten is more abstract than simply adding the word ‘ten’ as in the languages of Categories I and II. Additionally, the second ‘ten’ is in the illative case. In North Sámi, the ‘second’ undergoes consonant gradation, while the Skolt Sámi ‘second’ is reduced to just a consonant. This reduction of the middle morpheme makes Skolt Sámi less transparent than the other languages in Category III. The Category IV counting system is even more abstract than Category III, because the ‘second ten’ appears as just ‘second’ in the partitive case. Table 8 shows the transparency of the studied numerals compared to Welsh, categorized into three groups.

Table 8.

The numerals 11–19 in comparison with the structure in Standard Welsh.

The Standard Welsh numerals 11–19 are rhythmic and repetitive, and except for fourteen, all of them have three syllables. The numerals 11–19 in the Sámi and Kven languages are rhythmic and repetitive, too, but the number of syllables varies, as Table 9 shows.

Table 9.

The number of syllables in the numerals 11–19.

Skolt Sámi numerals have two syllables, except for 17, which has three. Thus, the Skolt Sámi numerals 11–19 are even shorter than the Welsh ones. All Kildin Sámi numerals have three syllables, almost the same as in Standard Welsh. The other Sámi numerals are longer: all South and Ume Sámi numerals have four syllables, while all numerals in Lule and Pite Sámi have five. The Inari Sámi numerals have five syllables, except for 11, 15, and 16, which have four. The North Sámi numerals 11–19 have six syllables, but in spoken language, the ‘nuppelohkái’ part of the word is abbreviated to ‘nupp’lohkái’, or nuppe-lot, which results in five-syllable numerals.

The Kven numerals 11–19 have four syllables, except for 17, 18, and 19, which have five. In the spoken Kven language, the numerals 11, 12, 15, and 16 have three syllables (Söderholm, 2017) because of apocope in the words yksi, kaksi, viisi, and koosi. This is similar to how Nelson and Toivonen (2000), in Inari Sámi (N&T) in Table 9, describe Inari numerals. This reduces the number of syllables by one.

4. Discussion

This study enlightens the research question: How may the use of Sámi and Kven numerals support children’s understanding of the base-10 numeration system? Two sub-questions are answered: (a) What are the structures of the Sámi and Kven counting systems?; and (b) how do Sámi and Kven counting systems compare to the Standard Welsh system? Based on the analysis of the two sub-questions, we discuss how the use of Sámi and Kven numerals may support children’s understanding of the base-10 numeration system.

For the numerals 11−19, South, Ume, Pite, and Lule Sámi languages clearly follow a transparent structure that is comparable with Standard Welsh. The other Sámi languages and Kven differ more significantly, because they follow a structure that focuses on the move toward filling up the second ‘ten’. Kven and Skolt Sámi are further from Standard Welsh than the other languages because some morphemes are implicit. Therefore, we conclude that the structures of Skolt Sámi and Kven numerals are less transparent than the structures of North, Inari, and Kildin Sámi languages. All Sámi and Kven numbers for twenty are ‘two ten’ as in Standard Welsh.

In comparison to Norwegian (as well as English and Swedish), the Sámi and Kven numeral structures in the range 11−20 are regular and systematic. These findings show that the structure of these numerals in the Sámi and Kven languages may support what Thanheiser and Melhuish (2018) identify as important: (a) children’s development toward being able to group ten ‘ones’ into a unit of one ‘ten’, and (b) understanding ‘ten’ as both ten ‘ones’ and one ‘ten’ simultaneously. The South, Ume, Pite, and Lule Sámi languages focus on building a new number upon the first ‘ten’. These languages may give stronger support for grouping ten ‘ones’ into a unit of one ‘ten’ than those who focus on the second ‘ten’. Regarding the Skolt Sámi and Kven numerals 11–19, there are implicit morphemes. This implies that the child has to decipher a ‘code’ in order to understand the counting system. It is well known from other areas of mathematics education that invisible or implicit symbols can be complicated to interpret for young learners. Brekke (2002) for instance, points to challenges for the student if the teacher does not explain the difference in the interpretation of 3 ½ and 3a; while there is an invisible plus symbol between 3 and ½, there is a hidden multiplication symbol between 3 and a. Thus, Skolt Sámi and Kven languages may give less support to young learners than the other languages in our study.

Thus, Skolt Sámi and Kven languages may give less support than the other languages in our study.

The Welsh numerals are longer than the English ones, but except for Skolt Sámi, the Sámi languages have longer numerals than Welsh. The longest ones are found in North Sámi, where each numeral from eleven to nineteen has six syllables, whereas the equivalent numerals in Standard Welsh vary between three and four syllables. However, in everyday speech, people shorten the long Sámi numerals. Most North Sámi speakers shorten the numerals, particularly when counting quickly. The Sámi Learning Center (Ravna, 2017) provides an example by Aslak Pieski from Ohcejohka; each numeral from one to ten has only one syllable, while each numeral 11–19 has two. Pieski shortens the numerals more than most people do. The numerals 11–19 are shortened according to a system where the first syllable of the numeral is kept and combined with -lo, which is the first syllable of logi, ten. For instance, guhtta-nuppe-lohkái, sixteen, is reduced to gu-b-lo, which has only two syllables. This shortening is reminiscent of the Skolt Sámi -m-lo.

Regarding the numerals from 21 to 90, there are two ways of counting in North Sámi: the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ way of counting (Nickel, 1994). The ‘old’ way continues the structure of the numerals 11−19. Here, 21 is okta-goalmmát-lohkái, which means ‘one-third-ten’, where ‘ten’ is in the illative case, so the translation is ‘one toward the third ten’. The ‘new’ way of counting follows the same structure as the South and Ume Sámi numerals 11−19. Here, 21 is guokte-logi-okta, which means ‘two-ten-one’. Nickel (1994) claims that the ‘new’ way of counting is similar to the Norwegian way of counting for numerals 21−99. The ‘old’ way of counting is only used up to 90; larger numbers are only counted in the ‘new’ way. The ‘old’ way is not much in use. The native North Sámi speaker Ellen Margrethe Siri Skum (personal communication, 19 July 2025) has experienced both the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ way of counting for numbers larger than 100. She herself uses the ‘old’ way for numbers 120−130; for example, 127 is čuođi ja čieža-goalmmat-lohkái, which means ‘hundred and seven-third-ten’, where ‘ten’ is in the illative case.

Planas and Civil (2013) share a concern about the social and cognitive impact of policies that mark one language as more powerful than another, particularly when those affected are from non-dominant language groups. They highlight the two metaphors, language-as-resource and language-as-political. Language-as-resource represents a potential for thinking and doing, and more specifically, for learning and teaching mathematics. Language-as-political, on the other hand, represents a potential for transformation through processes that place certain languages and their speakers at a distinct disadvantage. The Norwegianization process that caused Sámi and Kven language loss (Høybråten et al., 2023) is an example of language-as-political. The Norwegian Parliament established an annual special Sámi fund in the national budget in 1851. This fund was intended to bring about a change in language and culture (Minde, 2005). Language became both a measure and a symbol of the success or failure of the Norwegianization policy. Language-as-a-resource represents the potential for thinking and doing in Sámi, and we expect that the use of Sámi (and Kven) numerals in education will contribute to children’s understanding of the base-10 system.

5. Conclusions

A study of the structure of the numerals 11–19 in Sámi and Kven languages, together with comparisons with Standard Welsh, shows that the numerals in all these languages consistently follow regular structures that can make sense to young learners. Our study concludes that Sámi and Kven numerals may provide children with more support in grasping the base-10 system than the Norwegian and Swedish numerals do.

The Standard Welsh numerals 11–19 are rhythmic and repetitive, and except for fourteen, all have three syllables. The numerals 11–19 in the Sámi and Kven languages are rhythmic and repetitive, too. However, the number of syllables varies between the Sámi languages. Most Skolt Sámi numerals have only two syllables, and all Kildin Sámi numerals have three. These have fewer or the same number of syllables as the Welsh ones. The number of syllables in the other Sámi and the Kven numerals varies between four and six. North Sámi and Kven numerals 11–19 are often shortened in daily speech, while Skolt and Inari Sámi numerals are represented in shortened forms.

Our study of the structure of the numerals in Sámi and Kven languages gives reasons to believe that students who speak South, Lule, Ume, and Pite Sámi will most likely grasp the base-10 system more easily if they use the Sámi numerals instead of the Norwegian ones. Our study also indicates that children’s use of Kildin, Inari, and North Sámi numerals has the potential to support children’s understanding of the base-10 system because the system is explicit and consistent. The Skolt Sámi and Kven numerals follow clear structures, but these structures are not transparent because of implicit morphemes. Compared to the other Sámi languages, these two languages are expected to provide less support for children’s understanding of the base-10 system. In contrast to Norwegian (and English), the Sámi and Kven languages use a numeral for 20 that directly translates to ‘two ten’, which can support children’s understanding.

As part of schools’ approach to the heterogeneity of Sámi cultures, we suggest that Sámi and Kven students explore similarities and differences between their own counting system and those of one or more other Sámi languages. In particular, we expect that students with languages Kildin, North, Inari, and Skolt Sámi, as well as Kven, would benefit from counting in one of the languages South, Ume, Lule, and Pite Sámi, and vice versa. Students can also investigate how numerals are shortened in daily speech. This can be done through open investigative mathematics tasks, where parents, relatives, and other society members might support and contribute to the students’ education. Our study lays the foundation for a more in-depth study of how children grasp the base-10 system when teachers and parents consistently use Sámi and Kven numerals. Our conclusion is that including Sámi and Kven numerals in the mathematics curriculum aligns with the recommendations of the TRC report (Høybråten et al., 2023). Given the structure of Sámi and Kven numerals, we see great potential for their inclusion to support Sámi and Kven children’s understanding of the base-10 system, which is fundamental for further learning in school mathematics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.F. and Á.K.P.; methodology, A.B.F. and Á.K.P.; validation, A.B.F. and Á.K.P.; formal analysis, A.B.F. and Á.K.P.; investigation, A.B.F. and Á.K.P.; resources, A.B.F. and Á.K.P.; data curation, A.B.F. and Á.K.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.F.; writing—review and editing, A.B.F. and Á.K.P.; visualization, A.B.F. and Á.K.P.; project administration, A.B.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The research data in this article consist of numerals in different Sámi languages and Kven. These are available in dictionaries that appear in the list of references.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to many individuals who have spent time and shared their knowledge. We want to thank the advisors at Sáme Giellagálldo for their contributions regarding the Lule Sámi language, and Katarina Barruk for her contribution regarding the Ume Sámi counting system. We thank David Andrew Hjelleset and his Welsh friends George Lynch, Isobel Ruby, and Bedwyr Hughes; their contribution to the description of the Welsh counting system was very important. We also thank Hilja Huru and Mikko K. Heikkilä for their comments on the Kven counting system.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Antonsen, L. (2021). «Lei niogtredve go byggiimet» Om unormerte lån fra norsk i samisk talespråk. In K. Hagen, G. Kristoffersen, Ø. A. Vangsnes, & T. A. Åfarli (Eds.), Språk i arkiva—Ny forskning om eldre talemål frå LIA-prosjektet (pp. 179–200). Novus forlag. Available online: https://omp.novus.no/index.php/novus/catalog/view/19/29/1044 (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Aunio, P., Hautamäki, J., Heiskari, P., & van Luit, J. E. H. (2006a). The early numeracy test in finnish: Children’s norms. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 47, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aunio, P., Niemivirta, M., Hautamäki, J., Van Luit, J. E. H., Shi, J., & Zhang, M. (2006b). Young children’s number sense in China and Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(5), 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC Cymru Wales. (2002). Some basic rules of Welsh grammar. BBC. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/wales/learnwelsh/pdf/welshgrammar_allrules.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Brekke, G. (2002). Kartlegging av matematikkforståelse. Introduksjon til diagnostisk undervisning i matematikk. University of Sout-Eastern Norway. Available online: https://web01.usn.no/~panderse/KIMhefter/kimgammeldiag.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Broderstad, E. G. (2022). Sámi education betweenlaw and politics—TheSámi-Norwegian context. In T. A. Olsen, & H. Sollid (Eds.), Indigenising education and citizenship. Perspectives on policies and practices from sápmi and beyond (pp. 53–73). Scandinavian University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannemark, N. (2014). Norske talord i samisk tale i Guovdageaidnu. Maal Og Minne, 106(2), 131–154. Available online: https://ojs.novus.no/index.php/MOM/article/view/221/219 (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Dowker, A., Bala, S., & Lloyd, D. (2008). Linguistic influences on mathematical development: How important is the transparency of the counting system? Philosophical Psychology, 21(4), 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds-Wathen, C. (2019). Linguistic methodologies for investigating and representing multiple languages in mathematics education research. Research in Mathematics Education, 21(2), 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds-Wathen, C., Owens, K., & Bino, V. (2019). Identifying vernacular language to use in mathematics teaching. Language and Education, 33(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyhn, A. B., Partapuoli, Á. K., & Ravna, P. (2024). Hvorfor det er nødvendig med en samisk parallell likeverdig læreplan i matematikk. Rapport fra faggruppe nedsatt av Sametinget [Report]. Sámediggi—The Sámi Parliament. Available online: https://sametinget.no/_f/p1/i4c928b3b-9279-45ba-ae6d-2dcc914fbdf2/hvorfor-det-er-nodvendig-med-en-samisk-parallell-likeverdig-lareplan-i-matematikk.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Giellatekno. (2024). Generer samiske tallord. Giellatekno. Available online: https://giellatekno.uit.no/num.nob.html (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Helander, N. Ø. (2012). Norgga beale oahppoplána doaibmi guovttegielatvuohta—Mo dan meroštallat. Sámi Diedalaš Áigečálá, 8(2), 47–53. Available online: https://site.uit.no/aigecala/sda-2-2012-nils-oivind-helander/ (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Hohepa, M. K. (2006). Biliterate practices in the home: Supporting indigenos language regeneration. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 5(4), 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høybråten, D., Bjørklund, I., Gurák, A. K., Hermanstrand, H., Kjølaas, P. O., Lane, P., Myrvoll, M., Niemi, E., Semb, A. J., Somby, L. I., Syse, A., & Zachariassen, K. (2023). Sannhet og forsoning—Grunnlag for et oppgjør med fornorskingspolitikk og urett mot samer, kvener/norskfinner og skogfinner. Rapport til Stortinget fra Sannhets og forsoningskommisjonen. Sannhets- og Forsoningskommisjonen. Available online: https://www.stortinget.no/globalassets/pdf/sannhets--og-forsoningskommisjonen/rapport-til-stortinget-fra-sannhets--og-forsoningskommisjonen.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Jannok Nutti, Y. (2013). Indigenous teachers’ experiences of the implementation of culture-based mathematics activities in Sámi school. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 25, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, A. H., & Somby, D. N. (2023). Logut. Alie Hætta Karlsen. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MdJPKZZuf2A (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Knutsen-Duolljá, S.-E., Gaski, H., & Theil, R. (2024, May 21). samisk (E. Bolstad, Ed.). Store Norske Leksikon. Available online: https://snl.no/samisk (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Lipka, J. (2024, October 14–16). How yup’ik counting is a pathway to mathematics, culture, and creativity. 2nd Indigenous Mathematics Education Conference—IndigMEC2, Guovdageaidnu, Norway. Available online: https://samas.no/en/a/research/academic-events/indigmec2-conference (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Meaney, T. (2003). An indigemous community doing mathematics curriculum development. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 13(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menninger, K. (1969). Number words and number symbols [zahlwort und ziffer]. The MIT Press. (Original work published 1958). [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K. F., & Stiegler, J. W. (1987). Counting in Chinese: Cultural variation in a basic cognitive skill. Cognitive Development, 2(3), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minde, H. (2005). Assimilation of the Sámi—Implementation and consequences. Gáldu Čála—Journal of Indigenous Peoples Rights, 2(3), 6–33. Available online: http://galdu.custompublish.com/getfile.php/3307993.2388.dvvstfwfxw/mindeengelsk (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development. (2007). The sami act. Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/the-sami-act-/id449701/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Mortensen Krane, M. (2024). Stortingsvedtak. The Storting. Available online: https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Vedtak/Vedtak/Sak/?p=94524 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Beaton, A. E., Gonzalez, E. J., Kelly, D. L., & Smith, T. A. (1998). Mathematics achievement in the primary school years: IEA’s third international mathematics and science report. TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center. Available online: https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss1995i/TIMSSPDF/amtimss.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., Kelly, D. L., & Fishbein, B. (2020). TIMSS 2019 international results in mathematics and science. Boston College, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center. Available online: https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2019/international-results/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- NAOB. (2024). tvenne. Det Norske Akademis Ordbok (NAOB). Available online: https://naob.no/ordbok/tvenne (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- NAOB. (2025). tjue. Det Norske Akademis Ordbok (NAOB). Available online: https://naob.no/ordbok/tjue (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Nelson, D., & Toivonen, I. (2000). Counting and the grammar: Case and numerals in Inari Sámi. In D. Nelson, & P. Foulkes (Eds.), Leeds working papers in linguistics (Vol. 8, pp. 179–192). Leeds University. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239486556_Counting_and_the_Grammar_Case_and_Numerals_in_Inari_Sami (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Nesheim, A. (1952). Samisk og norsk i lyngen. In A. Nesheim (Ed.), Sameliv. Samisk selskaps årbok 1951–1952. Sámi ællin. Sámi særvi jakkigir’ji 1951–1952 (pp. 123–129). Merkur Boktrykkeri. [Google Scholar]

- Nickel, K. P. (1994). Samisk grammatikk 2 (Vol. 2). Davvi Girji. [Google Scholar]

- Nilstun, C. (2025). partitiv (E. Bolstad, Ed.). Store Norske Leksikon. Available online: https://snl.no/partitiv (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Oahpa! (2025a). Consonant gradation. UiT-The Arctic University of Norway. Available online: https://oahpa.no/sme/gramm/stadieveksling.eng.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Oahpa! (2025b). The illative. UiT-The Arctic University of Norway. Available online: https://oahpa.no/sme/gramm/substantiv.eng.html#The+Illative (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Oahpa! (2025c). The locative. UiT-The Arctiv University of Norway. Available online: https://oahpa.no/sme/gramm/substantiv.eng.html#The+Locative (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Owen, K., Lean, G., Paraide, P., & Muke, C. (2018). History of number. Evidence from papua new guinea and oceania. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinxten, R. (2016). Multimathemacy: Anthropology and mathematics education. Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-26255-0 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Planas, N., & Civil, M. (2013). Language-as-resource and language-as-political: Tensions in the bilingual mathematics classroom. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 25, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quencasten. (2023). Kvenfestivalens minikurs i kvensk—Episode 2—Tall. Quencasten. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qa0s8S2Ljgg (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Ravna, E. (2017). Oaniduvvon logut 1. ovttas/aktan/aktesne. Available online: https://ovttas.no/sites/default/files/shortnumb1_30.wav (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Salminen, T. (2010). Europe and the caucasus. In C. Moseley, & A. Nicolas (Eds.), Atlas of the world’s languages in danger. UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187026 (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Sállto. (2023). BidumBagõ—pitesamisk/bokmål ordbok. Pitesamisk—Bokmål/bokmål—Pitesamisk. Available online: https://sallto.no/nytt/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/BidumBago_-_bidum-bokmal_2023-03.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Sámediggi. (2017). Sámásmuinna2 sámástamujna2 sámásthmujna2 saemesthmunnjien2. Nimbus Communication AB. Available online: https://www.sametinget.se/6225 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Sámediggi. (2025). Læreplan i matematikk 1.-10.trinn—samisk plan. Fastsatt som forskrift av Sametinget 10.10.2025. Sámediggi. Available online: https://sametinget.no/_f/p1/i65d2a7d5-a22c-40b4-94e8-ce442ca4d0fc/lareplan-i-matematikk-1-10trinn-samisk-plan.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Sámi Allaskuvla. (2024). About Sámi university of applied sciences. Available online: https://samas.no/en/node/204 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Simonsen, H. G. (2025). Apokope (E. Bolstad, Ed.). Store Norske Leksikon. Available online: https://snl.no/apokope (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Sjaggo, A.-C. (2015). Pitesamisk grammatik- en jämförande studie med lulesamiska. Senter for Samiske Studier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic & Professional. [Google Scholar]

- Söderholm, E. (2017). Kvensk grammatikk (P. Conzett, Trans.). Cappelen Damm akademisk. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thanheiser, E., & Melhuish, K. (2018). Leveraging variation of historical number systems to build understanding of the base-ten place-value system. ZDM Mathematics Education, 51(1), 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theil, R. (2024). kvensk (E. Bolstad, Ed.). Store Norske Leksikon. Available online: www.https://snl.no/kvensk (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Thomas, E. M., & Gathercole, V. C. M. (2003, April 30–May 3). Minority language survival: Obsolescence or survival for welsh in the face of English dominance? The 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism, Tempe, AZ, USA. Available online: http://www.lingref.com/isb/4/174ISB4.PDF (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Zaslavsky, C. (1996). The multicultural math classroom. Bringing in the world. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).