From First-Year Dreams to Sixth-Year Realities: A Repeat Cross-Sectional Study of Medical Students’ Specialty Preferences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Avidan, A., Weissman, C., Elchalal, U., Tandeter, H., & Zisk-Rony, R. Y. (2018). Medical specialty selection criteria of Israeli medical students early in their clinical experience: Subgroups. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 7(1), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burack, J. H., Irby, D. M., Carline, J. D., Ambrozy, D. M., Ellsbury, K. E., & Stritter, F. T. (1997). A study of medical students’ specialty-choice pathways. Academic Medicine, 72(6), 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, J., DesJardins, S., & Gruppen, L. (2021). Diversity of the physician workforce: Specialty choice decisions during medical school. PLoS ONE, 16(11), e0259434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarny, M. J., Faden, R. R., Nolan, M. T., Bodensiek, E., & Sugarman, J. (2008). Medical and nursing students’ television viewing habits: Potential implications for bioethics. The American Journal of Bioethics, 8(12), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, L., de Wildt, G., Benyamini, Y., Ramkumar, A., & Adams, R. (2024). Exploring the experiences of English-speaking women who have moved to Israel and subsequently used Israeli fertility treatment services: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 19(8), e0309265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J., Que, J., Wu, S., Zhang, Y., Liu, J., Chen, S., Wu, Y., Gong, Y., Sun, S., Yuan, K., Bao, Y., Ran, M., Shi, J., Wing, Y. K., Shi, L., & Lu, L. (2021). Effects of COVID-19 on career and specialty choices among Chinese medical students. Medical Education Online, 26(1), 1913785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikici, M. F., Yaris, F., Topsever, P., Filiz, T. M., Gurel, F. S., Cubukcu, M., & Gorpelioglu, S. (2008). Factors affecting choice of specialty among first-year medical students of four universities in different regions of Turkey. Croatian Medical Journal, 49(3), 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, L. M., Alvi, F. A., & Milad, M. P. (2017). Trends in malpractice claims for obstetric and gynecologic procedures, 2005 through 2014. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217(3), 340.e1–340.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasreiner, D., Dahmen, U., & Settmacher, U. (2018). Specialty preferences and influencing factors: A repeated cross-sectional survey of first- to sixth-year medical students in Jena, Germany. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haklai, Z., Applbaum, Y., Tal, O., Aburbeh, M., & Goldberger, N. F. (2013). Female physicians: Trends and likely impacts on healthcare in Israel. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 2(1), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B. L., Wolynn, R., Sidani, J. E., & Donovan, A. K. (2022). Using fictional medical television programs to teach interprofessional communication to graduating fourth-year medical students. Southern Medical Journal, 115(12), 870–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ie, K., Murata, A., Tahara, M., Komiyama, M., Ichikawa, S., Takemura, Y. C., & Onishi, H. (2018). What determines medical students’ career preference for general practice residency training?: A multicenter survey in Japan. Asia Pacific Family Medicine, 17(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israeli, A., Blumenthal, E. Z., Nemet, A., Zayit-Soudry, S., Pizem, H., & Mezer, E. (2025). Have gender and ethnic disparities in ophthalmology disappeared? Insights from a workforce-based study in Israel (2006–2021). Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 14(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. (2023). The impact of gendered experiences on female medical students’ specialty choice: A systematic review. The American Journal of Surgery, 225(1), 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortune, G. (2023). Medical education and training in Israel. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. E., Lim, F., Silver, E. R., Faye, A. S., & Hur, C. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on residency choice: A survey of New York City medical students. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0258088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J. P., Tancredi, D., Jerant, A., Romano, P. S., & Kravitz, R. L. (2012). Lifetime earnings for physicians across specialties. Medical Care, 50(12), 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levaillant, M., Levaillant, L., Lerolle, N., Vallet, B., & Hamel-Broza, J.-F. (2020). Factors influencing medical students’ choice of specialization: A gender based systematic review. eClinicalMedicine, 28, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiorova, T., Stevens, F., Scherpbier, A., & van der Zee, J. (2008). The impact of clerkships on students’ specialty preferences: What do undergraduates learn for their profession? Medical Education, 42(6), 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mazeh, H., Mizrahi, I., Eid, A., Freund, H. R., & Allweis, T. M. (2010). Medical students and general surgery—Israel’s national survey: Lifestyle is not the sole issue. Journal of Surgical Education, 67(5), 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, C., Henderson, A., Barlow, P., & Keith, J. (2021). Assessing factors for choosing a primary care specialty in medical students; A longitudinal study. Medical Education Online, 26(1), 1890901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McOwen, K. S., Whelan, A. J., & Farmakidis, A. L. (2020). Medical education in the United States and Canada, 2020. Academic Medicine, 95(9S), S2–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A. A., Khan, W. S., Abdelrazig, Y. M., Elzain, Y. I., khalil, H. O., Elsayed, O. B., & Ibrahim, O. A. (2015). Factors considered by undergraduate medical students when selecting specialty of their future careers. Pan African Medical Journal, 20, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querido, S. J., Vergouw, D., Wigersma, L., Batenburg, R. S., De Rond, M. E. J., & Ten Cate, O. T. J. (2016). Dynamics of career choice among students in undergraduate medical courses. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 33. Medical Teacher, 38(1), 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachoin, J.-S., Vilceanu, M. O., Franzblau, N., Gordon, S., & Cerceo, E. (2023). How often do medical students change career preferences over the course of medical school? BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotem, A. (2023). Report on salary expenditures in the healthcare system—Public hospitals for the year 2021. Israel Ministry of Finance, Wages and Labor Agreements Division. Available online: https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/dynamiccollectorresultitem/salary-supervisor-report-health-system-2021/he/salary-supervisor-reports_supervisor-report-health-system-2021-accessible-version.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Schroeder, H., Shacham, A., Amar, S., Weissman, C., & Schroeder, J. E. (2024). Comparison of medical students’ considerations in choosing a specialty: 2020 vs. 2009/10. Human Resources for Health, 22(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierles, F. S., & Taylor, M. A. (1995). Decline of U.S. medical student career choice of psychiatry and what to do about it. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(10), 1416–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soethout, M. B. M., ten Cate, T. J., & van der Wal, G. (2004). Factors associated with the nature, timing and stability of the specialty career choices of recently graduated doctors in european countries, a literature review. Medical Education Online, 9(1), 4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. physician workforce data dashboard. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/report/us-physician-workforce-data-dashboard (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Weissman, C., Tandeter, H., Zisk-Rony, R. Y., Weiss, Y. G., Elchalal, U., Avidan, A., & Schroeder, J. E. (2013). Israeli medical students’ perceptions of six key medical specialties. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 2(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, C., Zisk-Rony, R. Y., Schroeder, J. E., Weiss, Y. G., Avidan, A., Elchalal, U., & Tandeter, H. (2012). Medical specialty considerations by medical students early in their clinical experience. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 1(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y., Li, J., Wu, X., Wang, J., Li, W., Zhu, Y., Chen, C., & Lin, H. (2019). Factors influencing subspecialty choice among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 9(3), e022097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | 2019 Cohort (n = 124) 1 | 2024 Cohort (n = 98) 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.064 | ||

| Female | 71 (57%) | 68 (69%) | |

| Male | 53 (43%) | 30 (31%) | |

| Age | 24.00 (23.00, 25.00) | 24.00 (23.00, 25.00) | 0.3 |

| Ethnicity | 0.2 | ||

| Arab | 5 (4.0%) | 8 (8.2%) | |

| Jewish | 119 (96%) | 90 (92%) | |

| Birth order | 0.5 | ||

| First born | 54 (44%) | 44 (45%) | |

| Last born | 27 (22%) | 26 (27%) | |

| Middle child | 38 (31%) | 27 (28%) | |

| Only child | 5 (4.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Background in medicine | 29 (23%) | 42 (43%) | 0.002 |

| Fluency in number of languages | 0.4 | ||

| 1 | 9 (7.4%) | 10 (10%) | |

| 2 | 71 (59%) | 63 (64%) | |

| 3 | 38 (31%) | 21 (21%) | |

| 4 | 3 (2.5%) | 4 (4.1%) | |

| Parent is a doctor | 15 (12%) | 12 (12%) | >0.9 |

| Specialty | Preclinical, n = 171 | Clinical, n = 98 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthesiology | 0 (0%) | 4 (4.1%) | - |

| Cardiology | 3 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Dermatology | 2 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Emergency Medicine | 3 (1.8%) | 1 (1.0%) | >0.9 |

| ENT | 3 (1.8%) | 3 (3.1%) | 0.8 |

| Family Medicine | 6 (3.5%) | 6 (6.1%) | 0.5 |

| General Surgery | 5 (2.9%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.6 |

| Internal Medicine | 15 (8.8%) | 9 (9.2%) | >0.9 |

| Neurology | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (1.0%) | >0.9 |

| Neurosurgery | 6 (3.5%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.4 |

| Nuclear Medicine | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

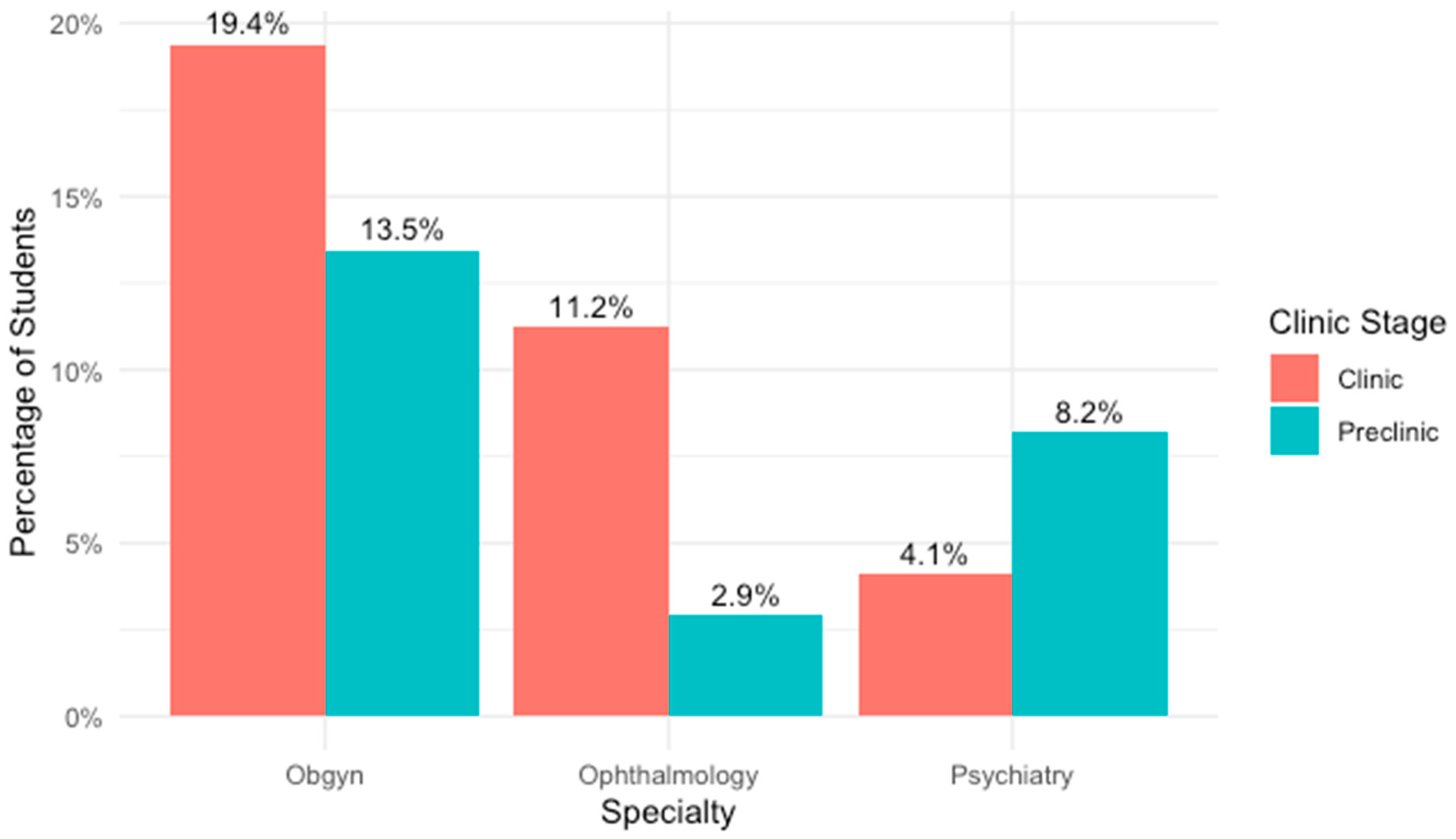

| OBGYN | 23 (13%) | 19 (19%) | 0.3 |

| Occupational Medicine | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Oncology | 15 (8.8%) | 2 (2.0%) | 0.054 |

| Ophthalmology | 5 (2.9%) | 11 (11%) | 0.012 |

| Orthopedic Surgery | 2 (1.2%) | 3 (3.1%) | 0.5 |

| Pathology | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Pediatrics | 23 (13%) | 12 (12%) | >0.9 |

| Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation | 2 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Plastic Surgery | 5 (2.9%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.6 |

| Psychiatry | 14 (8.2%) | 4 (4.1%) | 0.3 |

| Public Health | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Radiology | 2 (1.2%) | 2 (2.0%) | >0.9 |

| Surgery Undecided | 17 (9.9%) | 5 (5.1%) | 0.2 |

| Thoracic Surgery | 2 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Vascular Surgery | 2 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Urology | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Undecided | 15 (8.8%) | 13 (13%) | 0.3 |

| Specialty | Female, n = 68 | Male, n = 30 | p-Value | No Medical Background, n = 56 | Medical Background, n = 42 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthesiology | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.3%) | - | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.0%) | - |

| Cardiology | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Dermatology | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Emergency Medicine | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| ENT | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Family Medicine | 2 (2.9%) | 1 (3.3%) | >0.9 | 1 (2.0%) | 2 (4.1%) | >0.9 |

| General Surgery | 4 (5.9%) | 1 (3.3%) | >0.9 | 4 (8.2%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0.4 |

| Internal Medicine | 2 (2.9%) | 1 (3.3%) | - | 2 (4.1%) | 1 (2.0%) | - |

| Neurology | 0 (0%) | 2 (6.7%) | - | 1 (2.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | - |

| Neurosurgery | 4 (5.9%) | 0 (0%) | - | 2 (4.1%) | 2 (4.1%) | >0.9 |

| Nuclear Medicine | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| OBGYN | 19 (28%) | 0 (0%) | 0.003 | 9 (18%) | 10 (20%) | >0.9 |

| Occupational Medicine | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Oncology | 2 (2.9%) | 3 (10%) | 0.3 | 2 (4.1%) | 3 (6.1%) | >0.9 |

| Ophthalmology | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Orthopedic Surgery | 1 (1.5%) | 2 (6.7%) | 0.5 | 2 (4.1%) | 1 (2.0%) | >0.9 |

| Pathology | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Pediatrics | 10 (15%) | 4 (13%) | >0.9 | 5 (10%) | 9 (18%) | 0.4 |

| Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.3%) | - | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.0%) | - |

| Plastic Surgery | 1 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.0%) | - |

| Psychiatry | 5 (7.4%) | 2 (6.7%) | >0.9 | 3 (6.1%) | 4 (8.2%) | >0.9 |

| Public Health | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Radiology | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Surgery Undecided | 6 (8.8%) | 5 (17%) | 0.4 | 8 (16%) | 3 (6.1%) | 0.2 |

| Thoracic Surgery | 4 (5.9%) | 2 (6.7%) | >0.9 | 4 (8.2%) | 2 (4.1%) | 0.7 |

| Urology | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Vascular Surgery | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Undecided | 8 (12%) | 5 (17%) | 0.7 | 6 (12%) | 7 (14%) | >0.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hollander, Y.; Amitai, N.; Salem Yaniv, S.; Ben Shitrit, I.; Horev, A.; Golan Tripto, I.; Horev, A. From First-Year Dreams to Sixth-Year Realities: A Repeat Cross-Sectional Study of Medical Students’ Specialty Preferences. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111545

Hollander Y, Amitai N, Salem Yaniv S, Ben Shitrit I, Horev A, Golan Tripto I, Horev A. From First-Year Dreams to Sixth-Year Realities: A Repeat Cross-Sectional Study of Medical Students’ Specialty Preferences. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111545

Chicago/Turabian StyleHollander, Yael, Nir Amitai, Shimrit Salem Yaniv, Itamar Ben Shitrit, Anat Horev, Inbal Golan Tripto, and Amir Horev. 2025. "From First-Year Dreams to Sixth-Year Realities: A Repeat Cross-Sectional Study of Medical Students’ Specialty Preferences" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111545

APA StyleHollander, Y., Amitai, N., Salem Yaniv, S., Ben Shitrit, I., Horev, A., Golan Tripto, I., & Horev, A. (2025). From First-Year Dreams to Sixth-Year Realities: A Repeat Cross-Sectional Study of Medical Students’ Specialty Preferences. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111545