Mathematics with|in Conocimientos: A Mathematical Embodiment and Conscious-Raising Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

Based on how the stages of conocimientos that emerged during a mathematics-based youth participatory action research study, how can the seven stages of conocimientos be conceptualized within a mathematics context?

2. Critical Literacy and Critical Consciousness with Mathematics

Youth Participatory Action Research and Mathematics

3. Conocimientos

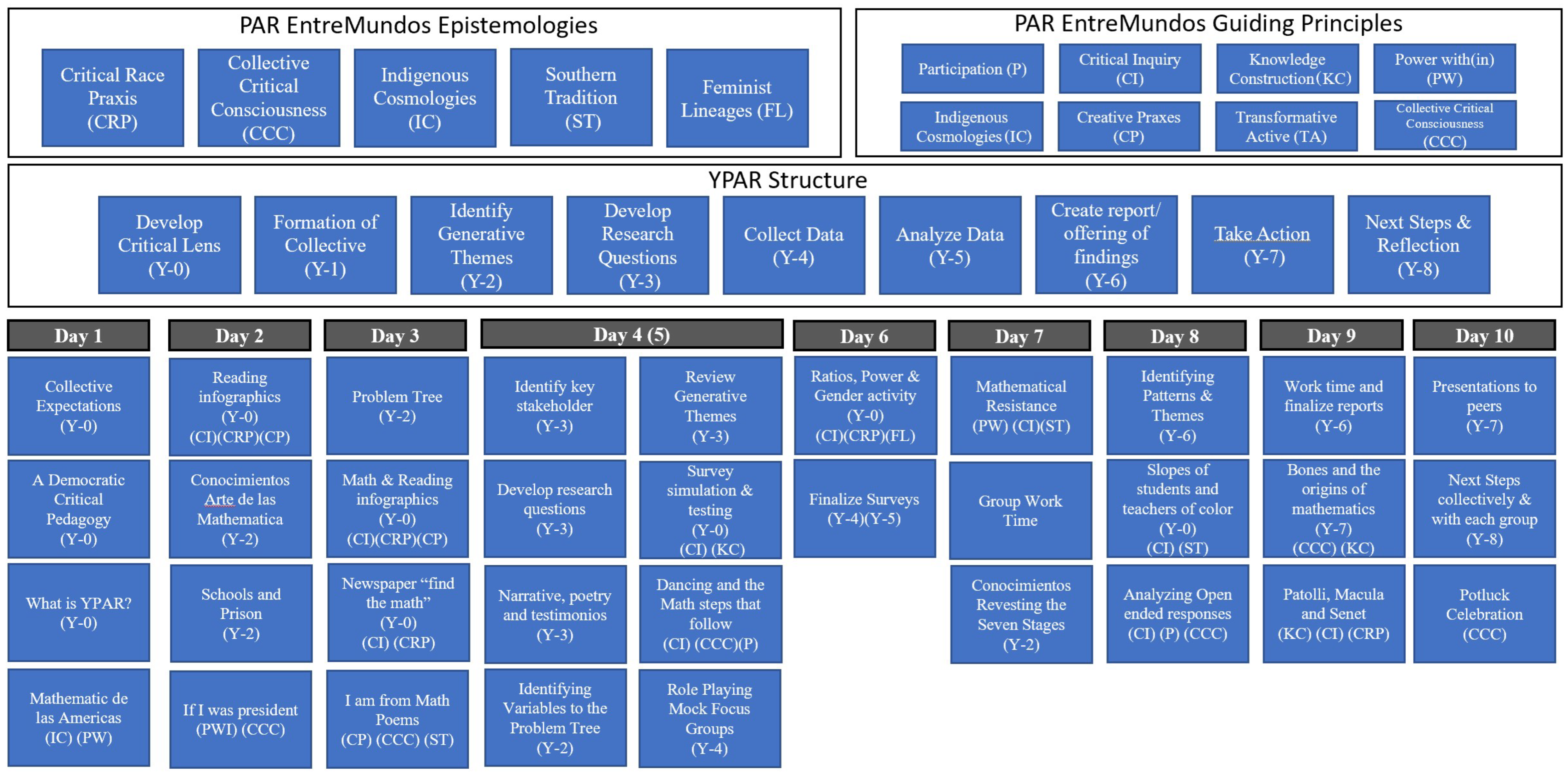

4. A Theoretical Framework of (Y)PAR EntreMundos

5. Methods

5.1. Context

5.2. Recruitment

5.3. REALM Methodological Structure

- I.

- Day 1: Establishing group expectations, defining YPAR, and beginning the formation of a collection.

- a.

- Mathematicas de las Americas is a presentation that focuses on the mathematics and science history of the Aztec, Maya, and Inca peoples. The presentation was created to connect both the guiding principles of Indigenous cosmologies and allow youth the opportunity to reflect on the power with(in).

- b.

- Patolli, the oldest known board game from the Americas, was played to allow youth to get to know each other (formation of a collective) by playing a game that allowed them to explore probability, specifically the expected values of outcomes. Additionally, this connects mathematics to Indigenous cosmologies.

- II.

- Day 2: Developing a critical lens and identifying generative themes.

- a.

- Infographic-centered mathematical literacy (knowledge) is a way to develop a critical understanding of the world while learning about societal injustices.

- b.

- Music, as a creative praxes, was used to help youth reflect on societal injustices and issues in their math class. Youth were asked what they would do if they were the president of the country and then if they had complete control of their math class.

- III.

- Day 3: Developing a critical lens and reflecting on generative themes.

- a.

- b.

- Poems were created using an I am Math poem template (reference Appendix A) as a creative praxes to identify generative themes.

- IV.

- Day 4 and 5: Developing a research question and research training.

- a.

- Youth were trained to be researchers.

- i.

- How to take field notes.

- ii.

- How to write observation memos.

- iii.

- How to conduct interviews and focus groups.

- iv.

- Survey design.

- 1.

- Open-ended (qualitative).

- 2.

- Yes/No: check all that apply, ranking and Likert (quantitative).

- v.

- Survey pilot testing.

- V.

- Day 6: Developing a critical lens, collecting data, and beginning to analyze data.

- a.

- A ratio of power activity connected the gender wage gap to the disproportionate number of men to women in positions of power. The activity shows how ratios can help develop a critical lens and the importance of knowing how to read and communicate with mathematics.

- VI.

- Day 7: Developing a critical lens and analyzing data.

- a.

- Mathematics problems contextually grounded around the Delano grape strike and the Black Panther Party’s free breakfast program connect history to math.

- VII.

- Day 8: Developing a critical lens, analyzing data, and creating reports.

- a.

- Comparing slopes of Students and Teachers of Color over the last seventeen years allowed youth to see at what rate their school is changing. The activity allows for developing a critical lens on how to use data to compare variables over time. In this case, the rate of change in Students of Color versus Teachers of Color in their school district.

- VIII.

- Day 9: Analyzing data and creating reports.

- a.

- Origins of mathematics, a description of the oldest known mathematical artifact, the Lebombo Bone, circa 35,000 BC, along with the game Gebet’a (also known as mancala), circa 700 BC, showed the African origins of mathematics.

- IX.

- Day 10: Present reports and reflect on the next steps.

- a.

- Youth presented the graphs, charts, art, and infographics they created.

6. Data

Data Analysis

7. Findings

7.1. El arrebato: A Catalyst for Mathematics

The difference between the math we’ve learned in the past 2 weeks and what we learn at school is that the math we learned here was connected to some part of history or poetry, and I’ve learned something new while doing math, but at school they don’t tie math to outside stories, it’s just all about math. … One thing I would tell my math teacher to change [in] the way they teach would be that connecting math to the real world have so many kids to get involved, it would have their attention more, and maybe more students would pass.

7.2. Nepantla: Embracing Infinity Nested in Infinity

7.3. Compromison: Mathematics Can Change the World

Youth Voice 1: Seeing where math comes from makes me feel like a mathematician, because math is everywhere.Youth Voice 2: I think that inequality should be taught in math class because people need to be informed about the truth in society.

7.4. Putting Coyolxauhqui Together: Reading Mathematics to Know Self and World

7.5. The Blow up: Meeting Others to Write Mathematics

7.6. Shifting Realities: Counting Our Acts of Resistance

I really hope middle school students can have the opportunity of learning how they can use math in the real world. I remember asking my sister how can fractions be used and she said for splitting foods like apples. But in truth fractions can be used for so much more.

7.7. Coatlicue: The Power and Fear of Knowing Mathematics

7.8. Discussion: Reconceptualization of Mathematics with Conocimientos

7.9. Implications: For Our Spirit

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Daily Reflection Prompts

Appendix B. Methodological Companion for M|C

- (1)

- Familiarization with the data was achieved by reviewing each journal, all teaching presentations, audio of whole-group sessions, teaching memos, and all additional artifacts. During this step, audio recordings of teaching were reviewed multiple times in parallel with the presentation slides. Research memos of the experience after teaching/facilitating each activity were also re-read. Additionally, mathematical work and the youths’ daily reflections on the activity were reviewed. The goal of this step is to bring the data to life, foregrounding the analysis of the observed experience.

- (2)

- Coding can be performed inductively or deductively at this stage. For this study, deductive codes were utilized given the utilization of Anzaldúa’s seven stages of conocimientos. Based on step 1, it was determined that youth reflections were the most appropriate data to analyze, as they represented what they experienced in their own voices. Coding using the seven stages of conocimientos was completed; Appendix B, Table A1, gives a simplified description of each of the seven stages along with an example from the data. The simplified description was used in conjunction with the definitions of the seven stages of conocimientos, reference Table A1.

| Stage | Simplified Description | Excerpt Example |

|---|---|---|

| el arrebato, C1 | Things that cause discomfort | Although I love a-ha moments, one word [to describe math in school]! Confused. |

| nepantla, C2 | Comparisons and definitions of worlds | Math can be used in many ways to show records from sports of all sorts and to also the diversity of places like schools. |

| Coatlicue, C3 | The pain of knowing|tied to (negative) history | Why don’t our teachers tell us the “truth” about our Ancestors and where math actually comes from? |

| compromison, C4 | The process of change or knowing change can happen | Math can be used to describe the world we live in and change it for the better. |

| putting Coyolxauhqui together, C5 | Comparing the past to the present self—the connection between worlds/ideas. | I wasn’t only learning slope but I was learning the rate of admin and teachers of color decreasing from schools. |

| the blow up, C6 | Being aware of others and learning from them. Growing from pushback. | It surprised me how it really connected to who I am and who we are. |

| shifting realities, C7 | Enacting Spiritual Activism—collective action | Because of this program I can tell my math teacher to teach us of our deep math history to encourage us to use this skill to better our community and better the lives of those around us. |

- (3)

- Searching for themes can be achieved with a wide array of methods of conducting qualitative analysis. In this study, content analysis (Neuendorf, 2016) was conducted to provide a summative view of the observed codes (reference Appendix B, Table A2) to better understand emerging themes across the data.

| Code | J0 | J1 | J2 | J3 | J4 | J5 | J6 | J7 | J8 | J9 | J10 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1, el arrebato | 10 | 7 | 7 | 11 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 60 |

| C2, nepantla | 17 | 14 | 12 | 23 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 29 | 144 |

| C3, Coatlicue | 3 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 15 | 47 |

| C4, compromison | 4 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 13 | 67 |

| C5, putting Coyolxauhqui together | 3 | 1 | 11 | 8 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 12 | 16 | 83 |

| C6, the blow up | 1 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 18 | 17 | 74 |

| C7, shifting realities | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 12 | 41 |

| Total | 39 | 38 | 44 | 63 | 49 | 20 | 36 | 41 | 26 | 54 | 106 | 516 |

- (4)

- Reviewing themes. Building on the content analysis, frequencies were translated to percentages to further review the themes per youth. Table A3 shows the percentage of each code observed for each youth with a density mapping. The density mapping for each value in each column used the darkest color for the highest value and the lightest for the lowest value. For example, in the Y6 column, the cell in row C2 has the darkest background because 27.54 is the greatest percentage among all cells in the column, and row C6 in the same column has the lightest background because 10.14 is the least-greatest percentage. The density mapping can be useful to understand how themes/codes interact with each other across youth. Paired with Table A2, which shows how the themes emerged over time, this level of analysis communicates that the seven stages of conocimientos were experienced by youth and there is evidence to show that consciousness shifts and develops because of the REALM curriculum.

| Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | Y4 | Y5 | Y6 | Y7 | Y8 | Y8 | Y10 | Y11 | Y12 | Y13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 11.36 | 16.07 | 14.63 | 5.00 | 14.29 | 8.70 | 6.06 | 13.51 | 5.56 | 13.51 | 11.63 | 16.67 | 11.11 |

| C2 | 29.55 | 17.86 | 24.39 | 40.00 | 50.00 | 27.54 | 27.27 | 21.62 | 33.33 | 21.62 | 39.53 | 25.00 | 25.93 |

| C3 | 11.36 | 12.50 | 14.63 | 0.00 | 7.14 | 11.59 | 9.09 | 8.11 | 5.56 | 8.11 | 9.30 | 8.33 | 11.11 |

| C4 | 6.82 | 12.50 | 9.76 | 20.00 | 7.14 | 15.94 | 15.15 | 13.51 | 8.33 | 16.22 | 9.30 | 16.67 | 14.81 |

| C5 | 15.91 | 16.07 | 19.51 | 20.00 | 14.29 | 14.49 | 18.18 | 16.22 | 16.67 | 16.22 | 9.30 | 16.67 | 16.67 |

| C6 | 18.18 | 12.50 | 14.63 | 15.00 | 7.14 | 10.14 | 18.18 | 16.22 | 19.44 | 16.22 | 9.30 | 13.89 | 14.81 |

| C7 | 6.82 | 12.50 | 2.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 11.59 | 6.06 | 10.81 | 11.11 | 8.11 | 11.63 | 2.78 | 5.56 |

- (5)

- Defining and naming themes requires revisiting the original codebook based on the data. It is important to note that, given that the themes are interdependent, and conocimientos is a shared experience, the analysis of youth’s reflections can be treated as a collective unit. Other forms of analysis set youth in their groups, treating each group as an individual. This only works because conocimientos is a collective and communal experience. If one student experienced one of the stages while working with others, then it is possible that they both experienced the same stage—just to different degrees. The findings of this study reflect the interdependency of each stage by pulling from multiple quotes or experiences to show how each of the seven stages of conocimientos are connected to mathematics.

- (6)

- Writing up. In thematic analysis, the writing up typically refers to the discussion and implications sections of a manuscript. In this case, the discussion and implications are the theorization that came from the previous five steps of thematic analysis. This is displayed in Table 4. Mathematics with|in conocimientos framework.

| 1 | Individual-collective is used to emphasize that consciousness and identity cannot be developed independent of others when learning mathematics. |

| 2 | Within, will be written as “with|in” for two reasons. The first reason pulls from conditional notation in mathematics where “A” given “B” is written as (A|B). Therefore, when I write conocimientos (with|in) mathematics or (C|M), I am saying conocimientos first given mathematics and (M|C) represents mathematics first given conocimientos. The second reason is similar to Anzaldúa’s (2015) theory of nos/otra where the “/” represents the bridge that divides “us” from “others” highlights that conocimientos and mathematical learning are separated, and the “|” in (C|M) and (M|C) represents the multiple barriers need to have a true union of conocimientos and mathematics in soceity. |

References

- Aleman, E., & Martinez, R. (2024). “It’s like they are using our data against us.” Counter-cartographies of AI literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 59(4), 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzaldúa, G. (2003). Now let us shift… the path of conocimiento… inner work, public acts. In G. Anzaldúa, & A. Keating (Eds.), This place we call home: Radical visions for transformation (pp. 540–578). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldúa, G. (2009). The gloria anzaldúa reader. In The gloria anzaldúa reader. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldúa, G. (2015). Light in the dark/Luz en lo oscuro: Rewriting identity, spirituality, reality. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, J., Cammarota, J., Berta-Avila, M., Rivera, M., Rodriguez, L., & Torree, M. (2018). PAR entremundos. A pedagogy of the Americas. Peter Lang Press. [Google Scholar]

- Battey, D., & Coleman, M. A. (2021). Antiracist work in mathematics classrooms: The case of policing. Journal of Urban Mathematics Education, 14(1B), 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berta-Ávila, M., Rivera, M., Ayala, J., & Cammarota, J. (2020). Living praxes and principles in PAR EntreMundos. In Liberatory practices for learning: Dismantling social inequality and individualism with ancient wisdom (pp. 19–45). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarota, J. (2017). Youth participatory action research: A pedagogy of transformational resistance for critical youth studies. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies (JCEPS), 15(2), 188–213. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota, J., & Fine, M. (Eds.). (2008). Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Edirmanasinghe, N. (2020). Using youth participatory action research to promote self-efficacy in math and science. Professional School Counseling, 24(1), 2156759X20970500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fals-Borda, O. (1987). The application of participatory action-research in Latin America. International Sociology, 2(4), 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fals-Borda, O., & Rahman, M. A. (1991). Action and knowledge: Breaking the monopoly with participatory action research. Apex. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, M. (2008). An epilogue, of sorts. In Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion (pp. 213–234). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (1973). Education for critical consciousness (Vol. 1). Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (Revised). Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (1998). Teachers as cultural workers. Letters to those who dare teach (The edge: Critical studies in educational theory). Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (2005). Literacy: Reading the word and the world. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, R. (2012). Embracing nepantla: Rethinking “knowledge” and its use in mathematics teaching. REDIMAT, 1(1), 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, R. (2015). Nesting in nepantla: The importance of maintaining tensions in our work. In Interrogating whiteness and relinquishing power: White faculty’s commitment to racial consciousness in STEM classrooms (p. 253). Peter Lang Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, R. (2017). Living mathematx: Towards a vision for the future. Philosophy of Mathematics Education Journal, 32(1), 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gutstein, E. (2006). Reading and writing the world with mathematics: Toward a pedagogy for social justice. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, A. (2016). EntreMundos/AmongWorlds: New perspectives on Gloria E. Anzaldúa. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, J. (2009). 13 “Still not saved”: The power of mathematics to liberate the oppressed. In Mathematics teaching, learning, and liberation in the lives of Black children (p. 304). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, I. P., Ieva, K., & Edirmanasinghe, N. (2024). Developing the foundation for YPAR in K–12 schools through counselor education. In Activating youth as change agents: Integrating youth participatory action research in school counseling (p. 42). Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D. B., Gholson, M. L., & Leonard, J. (2010). Mathematics as gatekeeper: Power and privilege in the production of knowledge. Journal of Urban Mathematics Education, 3(2), 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R. (2020). Mathematics reborn: Empowerment with youth participatory action research EntreMundos in reconstructing our relationship with mathematics [Doctoral dissertation, Iowa State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, R., & Aleman, E. (2025). Introduction: Speculative youth participatory action research: Narratives of imaginative social dreaming. Occasional Paper Series, 2025(53), 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R., Carpenter, C., Johnston, K., Shirude, S., & Zhou, Z. (2023). Poetic mathematical knowledge, cultural connections and challenging epistemic injustice. Teaching for Excellence and Equity in Mathematics, 14(2), 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R., Lindfros-Navarro, H., & Adams Corral, M. (2021). Mathematics with open arms. In J. Cammarota (Ed.), Liberatory practices for learning: Dismantling social inequality and individualism with ancient wisdom (pp. 69–91). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf, K. A. (2016). The content analysis guidebook. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Reza-López, E., Huerta Charles, L., & Reyes, L. V. (2014). Nepantlera pedagogy: An axiological posture for preparing critically conscious teachers in the borderlands. Journal of Latinos and Education, 13(2), 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severns, M. (2023). “I’m now always thinking about math”: Exploring mathematics identities, beliefs, and lived experiences through YPAR [Doctoral dissertation, City University of New York Hunter College]. [Google Scholar]

- Skovsmose, O. (2011). Critique, generativity and imagination. For the Learning of Mathematics, 31(3), 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Solorzano, D. G., & Bernal, D. D. (2001). Examining transformational resistance through a critical race and LatCrit theory framework: Chicana and Chicano students in an urban context. Urban Education, 36(3), 308–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, M. E., & Ayala, J. (2009). Envisioning participatory action research entremundos. Feminism & Psychology, 19(3), 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K. W. (2009). Mathematics, critical literacy, and youth participatory action research. New Directions for Youth Development, 2009(123), 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| el arrebato, C1 | The beginning of fragmentation and transformation. Known as the stage that kicks you out of your comfort zone, it represents moments where an individual is forced to react. |

| nepantla, C2 | The acknowledgment that in between two ideas, people, or physical places, there is a third entity composed partially of those two ideas. There is always a midpoint, always an in-between space. |

| Coatlicue, C3 | This is known as desconocimiento and reflects the pain of knowing. There is a need to change and reflect on one’s own history and trauma from knowing the truth. |

| Compromison (el compromise), C4 | This is the multiplicity of history, self, others, and the future. The world is constantly changing and is not static and hopeless. |

| putting Coyolxauhqui together, C5 | The reinvention of self and a complete understanding of the old self and the current self help in dismantling the difference between the two and creating a new self. |

| the blow up, C6 | This is the realization that you are no longer the person you were based on interactions with others. Here, learning from defeat and continuing to grow is sustained by connections/bridges made with others. |

| shifting realities, C7 | A spiritual transformation, being conscious of yourself and others, and the action taken in committing to collective change. |

| Guiding Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Participation. | Practitioners and stakeholders should be involved in all steps of research (design, data collection, analysis, and dissemination). |

| Critical inquiry. | The work needs to be grounded in critical race and decolonizing theories that examine the socio-historical, socio-political, and material contexts and conditions of our lives. |

| Knowledge co-construction. | Knowledge that informs action is produced in collaboration with communities, where researchers and research become a collective of knowledge producers/actors. |

| Power with(in) | The collective critically reflects on its own process, fosters trusting relationships of mutuality between members, examines power within the group, and engages in deep self-inquiry. |

| Indigenous cosmologies | In the spirit of an approach to PAR that is EntreMundos and that grows from the southern tradition, we see it as a way to reclaim and reimagine indigenous ways of knowing and engaging in this work as a healing process for the individual and community. |

| Creative praxes. | The methods for collecting and presenting data are embedded in the cultural and creative productions of the local community, which may include poetry, music, dance, theater, and other forms of cultural and artistic expressions. |

| Transformational action. | There is a commitment to conscious action and social change using creative praxes and engaged policy. |

| Concientizacion para la colectiva. | This work is part of a movement, not simply separate sets of isolated actions, whose goals include critical consciousness, social justice, and mutual liberation/emancipation from oppression. |

| Data | Description |

|---|---|

| Youth Journals | At the end of each activity or day (except the first journal), youth were asked to reflect on what they learned and how the learning made them feel. Before any activity, youth were asked to journal based on the prompts “What is math?” and “What do you expect over the next two weeks?” The journal is where youth wrote and worked on all but three activities. |

| Group Audio | Each group was audio recorded during the entire duration of REALM. |

| Whole Audio | An audio recorder was placed between the youth and me, capturing the audio of the entire room. |

| Teaching Memos | After each day, I wrote a memo reflecting on the lesson. |

| Additional Artifacts | Additional artifacts consisted of activities performed outside of the youth journals and consisted of problem trees, I am Math poems, newspaper from the math in the news activity, and worksheets used for the gender ratio activity. |

| Teaching Slides | The PowerPoints used to teach each day of the program were saved. |

| Final Presentations | The final products or presentations that each group of youth created. |

| Stage | Mathematical Embodiment |

|---|---|

| el arrebato, Mathematical Ruptures. | Mathematics is connected to emotions, from the surprise and joy of learning to the anxiety and fear created by mathematics. A challenging or interesting math problem or learning something that seems to break the rules. This is related to discovery. |

| nepantla, Multiplicity of Mathematics. | The wonder and the possibility of connections made while learning mathematics. Connections can be between learners, mathematical ideas, or between a wide range of physical and metaphysical forms of mathematics. This is the inherent tension of asset-based approaches and the struggle of incorporating culture into the mathematics classroom. |

| Coatlicue, Mathematical Feelings. | The pain of learning mathematics and other strong feelings associated with reflecting upon the mathematical world. Deeply connected to history and the lived experience. This is related to the impact of discovery. |

| compromison, Speculative Mathematics. | A mathematical imaginary between mathematical history and future mathematics that is not fixed. How people understand the history of mathematics can change just as much as the future of mathematics will change. |

| putting Coyolxauhqui together, Mathematical critical self-literacy. | Mathematical critical self-literacy. The ability to use mathematics to better understand how one undergoes internal transformation. Mathematics is used to reflect on and about self. |

| the blow up, Collective mathematical reflection. | Dialogue of mathematical learning in identifying that mathematics is already a part of each individual person. Mathematics works to interconnect people so that reflection is no longer about me and I. It is about us and we, in search of a collective mathematical identity. |

| shifting realities, Mathematical critical action. | Living with mathematics means using mathematics when no one is looking and when everyone is watching. This is the action associated with sharing mathematical knowledge for collective well-being. A community identity committed to action. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinez, R.; Bernal, G.E.; Peru, L. Mathematics with|in Conocimientos: A Mathematical Embodiment and Conscious-Raising Experience. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1508. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111508

Martinez R, Bernal GE, Peru L. Mathematics with|in Conocimientos: A Mathematical Embodiment and Conscious-Raising Experience. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1508. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111508

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinez, Ricardo, Gabrielle Elizabeth Bernal, and Larissa Peru. 2025. "Mathematics with|in Conocimientos: A Mathematical Embodiment and Conscious-Raising Experience" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1508. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111508

APA StyleMartinez, R., Bernal, G. E., & Peru, L. (2025). Mathematics with|in Conocimientos: A Mathematical Embodiment and Conscious-Raising Experience. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1508. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111508