1. Introduction

Teachers with significant physical or sensory disabilities (PSD) contribute to the education system in multiple ways. Their presence in schools creates opportunities for meaningful interactions that are otherwise very limited. Teachers with PSD serve as positive role models for overcoming challenges that can inspire all students, and they tend to form close and supportive relationships with students with special needs. Effective teachers with PSD can help reduce negative stereotypes about disabilities. In an era of teacher shortages, recruiting teachers with PSD can diversify the teaching force and add much-needed educators to the system. Moreover, employing them conforms with the broader goals of enhancing inclusion, equity and social justice (

Neca et al., 2022;

E. C. Parker & Draves, 2018;

Ware et al., 2022). Nonetheless, teachers with PSD seem to be under-represented within the teaching workforce (

Ware et al., 2022).

Research on inclusive education has primarily focused on students, whereas teachers with PSD remain an understudied population (

Neca et al., 2022;

Ware et al., 2022). To realize their potential contribution to the education system, a greater understanding of the challenges they face and proposing strategies for addressing them are needed. This is particularly true in the case of beginning teachers with PSD, since the first years of teaching are prone to attrition (

OECD, 2021). To address this knowledge gap, this study analyzed challenges raised by participants of an academic workshop designed for beginning teachers with PSD, as well as the solutions suggested by the workshop’s participants and facilitators. This knowledge is essential for improving the preparation and induction of teachers with PSD and preventing their attrition.

The literature review below begins by addressing workplace challenges for individuals with PSD. Next, it examines the challenges facing beginning teachers in general. It then focuses on the specific barriers faced by beginning teachers with PSD. Then, the support systems available for teachers, in general, are described, with particular attention to Communities of Practice (CoPs). Finally, the study context is presented: an academic workshop designed as a CoP to support beginning teachers with PSD in Israel.

1.1. Workplace Challenges Facing Individuals with PSD

In many countries, such as Canada (

Shahidi et al., 2023), the U.S. (

T. Parker & Peterson, 2025), New Zealand (

Ware et al., 2022) and Brazil (

De Oliveira Neto, 2023), individuals with PSD are legally entitled to participate in the workforce and receive reasonable accommodations for them to do so. Nonetheless, they face significant employment barriers (

US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2025). For example, although individuals with disabilities represent approximately 15–20% of the working-age population, they account for less than 5% of health care practitioners in the US and Canada (

Lindsay et al., 2023). Individuals with PSD report that employers are reluctant to hire them due to ableist stereotypes portraying them as less competent and overly dependent, as well as concerns about the costs of the accommodations and safety issues. As a result, they often delay disclosing their disability to potential employers until they have had a chance to demonstrate their knowledge, skills and experience, and they minimize the extent of the accommodations they require (

Lindsay et al., 2023;

Moloney et al., 2019;

T. Parker & Peterson, 2025).

Along with the quantity of rates of employment, the quality of available positions presents an additional challenge.

Shahidi et al. (

2023) found that individuals with disabilities in Canada are twice as likely to work in low-quality positions as compared to those without disabilities. These are insecure and unrewarding roles or “dead-end” positions that are beneath the worker’s skills and offer no opportunities for professional learning or promotion. Similarly, in the US, only 44% of individuals with significant visual impairment participate in competitive, integrated employment, compared with 80% of individuals without disabilities (

T. Parker & Peterson, 2025).

Workplace-related challenges persist even after securing employment. Individuals with PSD often face ableist prejudices, microaggressions, and marginalization that negatively affect their integration and promotion. These challenges are frequently exacerbated by absent or inadequate accommodations that impede work performance. In such circumstances, they are held fully accountable despite working in inaccessible environments. Fearing job loss, individuals with PSD typically avoid advocating for better accommodations, which intensifies their difficulties. Consequently, they often work significantly harder than their colleagues to maintain performance standards. Their sense of competence diminishes when they cannot meet expected benchmarks, negatively affecting their well-being. Disabilities can also result in social isolation at work. For example, deaf workers who have difficulty using oral language may find it challenging to communicate with colleagues, while workers with mobility issues may be unable to join colleagues for lunch or social outings (

De Oliveira Neto, 2023;

Elkins, 2025;

Lindsay et al., 2023;

Marathe & Piper, 2025). Interestingly, these challenges persist even in high-tech companies that are ostensibly committed to inclusion and diversity and actively seek to offer professional positions to people with PSD while accommodating their needs (

Marathe & Piper, 2025).

Teaching is no exception. As

Ware et al. (

2022) note, the education system strives to provide inclusive education to students with disabilities, but neglects teachers with disabilities. Teachers with disabilities, regardless of visibility, face doubts concerning their professional capabilities. They encounter a lack of awareness and understanding of the accommodations they need, as well as an unwillingness to provide them. These attitudes stem from the belief that teachers with disabilities are “flawed” and that it is their responsibility to compensate, not the workplace’s. As a result, teachers with disabilities must work harder in unfavorable conditions and often feel socially isolated (

Ware et al., 2022;

Williamson-Garner et al., 2025).

1.2. Typical Challenges Facing Beginning Teachers in General

The reality that beginning teachers face as they enter school is often very different from what they expected and hoped for, requiring them to address challenges across multiple areas (

Flores, 2020;

Veenman, 1984). As teachers, they need to plan several lessons each day as well as larger teaching units and cater to diverse students’ needs. These time-consuming tasks create a work overload that interferes with the work-home balance and may result in burnout. Classroom management issues and students’ misbehavior are particularly stressful. Learning the school’s norms, adapting to its climate, and socially integrating within the school staff are additional challenges that must be resolved (

den Brok et al., 2017;

Clandinin et al., 2015;

Schellings et al., 2023;

Symeonidis et al., 2023;

Zhukova, 2018). While addressing these challenges, beginning teachers’ learning trajectories are non-linear, exemplifying both progress and setbacks, and are largely affected by the contexts of their work (

Schellings et al., 2023).

Unsuccessful encounters with these challenges may motivate teachers to leave (

Flores, 2020;

Hong et al., 2018). Indeed, attrition rates among beginning teachers are high (

OECD, 2021). For example, nearly 50% of beginning teachers in the US leave within their first five years (

Goldhaber & Theobald, 2022), and over 30% leave in England (

Teaching Commission, 2024). In Israel, nearly 30% of teacher education graduates do not start teaching at all. An additional 20–30% leave teaching during the first five years (

Weissblai, 2023). Attrition has serious consequences: Beginning teachers may experience feelings of personal failure; students receive inadequate instruction; schools face disrupted work and social cohesion, and public resources invested in teacher preparation are wasted (

Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019;

Clandinin et al., 2015).

1.3. Beginning Teachers with PSD

Beginning teachers with PSD are in a particularly vulnerable position. In addition to being inexperienced, their disabilities may raise concerns among principals that could impede their employability (

Tal-Alon & Shapira-Lishchinsky, 2021). Principals worry about the cost and complexity of providing accommodations and that other teachers may need to take on extra duties. Furthermore, principals may fear that teachers’ PSD could compromise student safety, learning, or well-being. These concerns can be decisive, even for principals who strongly support inclusion and social justice (

Bargerhuff et al., 2012;

Tal-Alon & Shapira-Lishchinsky, 2021). Being aware of these concerns, teachers with PSD are often hesitant to fully disclose their disabilities during recruitment. They refrain from requesting accommodations to which they are legally entitled. Consequently, non-disclosure may compromise their health and further impede their ability to integrate into school and realize their unique potential contribution (

Tal-Alon & Shapira-Lishchinsky, 2019;

Wood et al., 2022). Such difficulties compound the typically severe obstacles facing all beginning teachers.

For teachers with PSD to thrive, they must be agentive, aware of their strengths and weaknesses, and actively seek means to function independently rather than passively depending on assistance (

Bargerhuff et al., 2012;

Williamson-Garner et al., 2025). Self-advocacy is essential: they need to articulate their needs for specific accommodations and may have to adapt them over time, based on the experience they gain. Such a proactive approach is necessary to gain colleagues’ respect for their professionalism and foster egalitarian collaboration, while mitigating feelings of isolation among the school staff (

Miller & Tal-Alon, 2024;

Ware et al., 2022;

Wood et al., 2022). Nevertheless, navigating self-advocacy effectively while avoiding potential backlash may require support.

1.4. Supporting Beginning Teachers in General

To help beginning teachers during the vulnerable entry phase of their career, several courses of action are proposed. Principals are advised to provide beginning teachers with work conditions that enable success, such as reduced teaching hours, provision of teaching resources and opportunities for professional development (

Podolsky et al., 2016). Mentor teachers, preferably ones who teach the same subject and age group, can support beginning teachers professionally, emotionally and socially (

Orland-Barak, 2016;

Zavelevsky & Lishchinsky, 2020). Mentors’ assistance is enhanced when principals are involved, express their interest in the beginning teachers’ progress and support their autonomy, while providing guidance (

Podolsky et al., 2016;

Zavelevsky & Lishchinsky, 2020). In some countries, beginning teachers participate in CoPs (

Kaplan, 2022;

Reeves et al., 2022;

Tynjälä et al., 2021).

1.5. Beginning Teachers’ Communities of Practice

CoPs are groups of professionals who meet frequently to share their knowledge and review their practices, with the aim of improving them. During discussions, implicit knowledge becomes explicit and is linked with knowledge from additional sources. Social interactions within CoPs are based on trust that is built over time. Successful communities manage to strike a balance between mutual support and trust on the one hand, and critical discussion of members’ practices on the other hand (

Wenger, 1998;

Wenger et al., 2023). Although the theoretical framework of CoPs was developed within other work contexts, they have become the ‘gold standard’ of teachers’ professional learning (

DuFour & DuFour, 2009;

Vangrieken et al., 2017).

Within beginning teachers’ communities, participants share their difficulties, reflect on their experiences, and consult with each other. Through shared stories, participants collaboratively interpret their experiences and construct their professional identities. When teacher educators facilitate such communities, they create an atmosphere of openness and trust, using relevant theories to help beginning teachers analyze their experiences and consider suitable courses of action (

Kaplan, 2022;

Tynjälä et al., 2021). This facilitation supports beginning teachers in connecting theoretical, experiential, and socio-cultural knowledge into an integrated whole and fosters metacognitive skills such as reflection and self-monitoring (

Tynjälä et al., 2021). The facilitators also encourage the formation of positive professional identity by emphasizing beginning teachers’ strengths while providing realistic feedback (

van Rijswijk et al., 2018). As active co-constructors of knowledge, beginning teachers are not passive recipients, but rather are equal partners in reciprocal learning. Through this combination of open and trusting peer collaboration, facilitated reflection, and integrated knowledge construction, beginning teachers’ communities empower participants by strengthening their sense of belonging and professional competence (

Kaplan, 2022). Due to these qualities, it was suggested that CoPs be established for teachers with disabilities as safe spaces where they can share their experiences and learn from each other (

Williamson-Garner et al., 2025).

1.6. The Study Context

This study took place in Israel, where beginning teachers’ induction spans three years. To start the induction process, teachers must be employed at least 33% of a full teaching position in a k-12 classroom. The first year is considered as a probation (internship). First-year teachers are obliged to participate in an academic workshop that is designed to cater to their needs. School principals must appoint a mentor teacher who is required to meet the first-year teacher regularly, at least once a week. The principal and the mentor must observe the first-year teacher’s work in the classroom at least twice, at mid-term and at the end of the school year, provide feedback, and share their evaluations with the Ministry of Education. These evaluations determine whether the first-year teacher ‘passes’ the probation year successfully and receives a teaching license or needs to repeat it. During their second year of teaching, they still have a mentor teacher and participate in a beginning teachers’ academic workshop, but for fewer hours. Finally, beginning teachers receive tenure after the end of the third year. However, for first-year teachers, the combination of support and the critical importance of successful evaluation may impede their willingness to openly expose their feelings and difficulties to their mentors. Workshop facilitators are not involved in the evaluation process and are therefore easier to consult with, yet they may be unfamiliar with the teachers’ schools or teaching subjects.

As for teachers with disabilities, Israeli law (

Knesset, n.d.) acknowledges the right of individuals with disabilities to fully participate in all areas of life and states that they must receive adequate yet ‘reasonable’ accommodations to enable this. Institutions that receive government funding must include at least 5% of employees with significant disabilities, although this requirement is very partially implemented. To support the inclusion of teachers with PSD, the Ministry of Education provides additional funding to absorbing schools that is gradually reduced after the first year of employment, and personal assistance to both school principals and teachers with disabilities (

Fairstain, 2019).

The current study follows an online academic workshop designed as a CoP for first-year teachers with PSD. The workshop was a joint initiative of Beit-Berl College of Education and the Ministry of Education. It was the first workshop specifically for teachers with PSD in Israel. First-year teachers with PSD could select this workshop from among the available options. The workshop also accepted second-year teachers with PSD who wished to participate.

The study’s research questions were:

What challenges did beginning teachers with PSD raise while consulting with their peers and the workshop’s facilitators?

To what extent were the challenges affected by their PSD?

What suggestions did the workshop’s participants and facilitators offer to overcome the challenges?

How did the challenge-centered discussions evolve throughout the year?

2. Method

This is a descriptive case study (

Yin, 2018) that followed the meetings of a beginning teachers’ workshop throughout one academic year. It uses the same dataset as another analysis (currently under review) that follows the development of the participants’ professional identity. This workshop was chosen as a unique and revealing case for several reasons. First, it was the first (and at the time, the only) workshop in Israel specifically designed to support beginning teachers with PSD. Second, it provided a safe space where teachers with PSD could share their experiences and consult with each other. Such opportunities are unavailable in typical workshops where participants with PSD are often the only ones with PSD, making them feel isolated. Finally, the facilitators were experienced special education teacher educators who could implement supportive strategies typically unfamiliar to other workshop facilitators and mentor teachers. Due to its uniqueness, this case had the potential to make a meaningful contribution to the existing knowledge about challenges facing beginning teachers with PSD and suggest potential support strategies.

However, choosing this case has some limitations: The participants’ registration in a workshop specifically for beginning teachers with PSD could indicate they needed assistance in overcoming PSD-related challenges. This self-selection could have increased both the range and the severity of the challenges being discussed. Therefore, the challenges raised in this workshop should not be taken as representative of what all teachers with PSD encounter, but rather as examples of challenges beginning teachers with PSD might face. The facilitators may have introduced additional bias by addressing certain topics while omitting others. Finally, the findings rely on a single data source—the workshop transcripts. Triangulation through real-time interviews or observations would have strengthened the study, but such data was not collected for ethical reasons.

2.1. Participants

The workshop took place during the 2021/2022 academic year. Its participants included three workshop facilitators (one male; all Hebrew-speaking special education teacher educators) and 16 teachers with PSD (14 first-year and two second-year teachers). Many of the first-year teachers had prior teaching experience, but, for various reasons, they were unable to complete their probation year successfully: some had previously failed, worked insufficient weekly hours, or provided extra-curricular support to small groups of students rather than teaching core curriculum hours. As noted above, participants selected this workshop from among other available options. The choice made by the two second-year participants is particularly notable, as they could have opted for second-year workshops requiring fewer teaching hours. Accordingly, the participants of this workshop are referred to as ‘beginning’ teachers and not as ‘first-year’ teachers.

Table 1 provides a summary of the participants’ background characteristics.

2.2. Data Sources

Transcripts of the audio recordings of the workshop’s 13 meetings, each lasting 90–120 min. Recordings make it possible to follow the discourse that took place in the workshop in real time.

2.3. Data Gathering

The facilitators recorded the meetings to study their own practice. A few months after the workshop ended, the facilitators asked the participants’ permission to analyze and publish the recordings’ contents, while disguising the participants’ identities. Sixteen of the 20 workshop participants agreed, and the others were deleted from the transcripts.

2.4. Author’s Positionality and Ethical Considerations

The author works at MOFET, a research institute hosting the administrative unit that supports the inclusion of teachers with PSD. The author was invited to the study by the project’s facilitators to help them analyze the data and received their permission to publish this paper. The author does not have authority relations either with the workshop participants who are employed by the Ministry of Education or with the facilitators who were employed by their college.

The teachers’ identities were disguised by removing identifying information and using pseudonyms. The facilitators were numbered since the male facilitator would be identifiable even with a pseudonym. The study was approved by the research institute’s ethics committee.

2.5. Data Analysis

The analysis utilized both discourse and thematic analysis research methods. First, the transcripts were read thoroughly to identify conversation sequences revolving around the discursive topic ‘challenge’. A new topic began when a beginning teacher introduced a challenge, either asking for a solution (through action or advice) or sharing how he or she overcame it. Such openings propelled a flow of ideas and responses that could be very short, for example, “thank you for sharing”, or very long. Long responses involved several speakers who suggested ideas and solutions, shared similar challenges, supported or objected to previous speakers, etc., until the topic was ended. In many cases, a topic ended with an explicit expression such as “thank you” or “very well”, whereas in other cases, a longer-than-normal pause was followed by an introduction of a different topic (

Chafe, 2015). This phase of discourse analysis resulted in a dataset of discourse segments, each evolving from the introduction of a challenge. Then, the segments were scrutinized to extract additional challenges that were mentioned as the topic developed, either by the first speaker or by other participants.

To answer the first research question, the dataset of challenge-related discourse was manually coded (using only MS Word and Excel), and segments were thematically analyzed according to

Kuckartz’s (

2002/2014) method.

Table 2 below presents examples of the coding process. The first round of coding was inductive, assigning codes that closely represented the challenges’ contents. For example, “the mentor teacher is too busy”. In the second round of coding, codes were merged into larger categories, such as “relationships with the mentor teacher”. Categories were assigned both inductively, based on the initial codes, and deductively, based on the literature on beginning teachers’ challenges. Finally, categories formed themes describing the areas to which the categories belong. The “relationships with the school staff” theme encompassed the categories: the dilemma of disclosing the disability; relationships with the principal or other administrators; staff prejudice or hostility, and the relationships with the mentor teacher. The “student motivation and behavior management” theme included student misbehavior and students’ lack of engagement. The “teaching practices” theme comprised addressing students’ needs through differentiated instruction, teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge, moral education, and infrastructure and workload. The “technological and bureaucratic procedures” theme included operating software and apps, navigating websites, understanding bureaucratic information, and completing registration procedures.

The number of occurrences of challenges within each category and each theme was counted. Challenges raised by different participants or by the same participant in different discourse segments were counted separately, whereas repetitions by the same participant within the same discourse segment were counted only once. The coded data was presented to one of the workshop’s facilitators for validation. The facilitator reviewed the coded discourse segments, as well as the category and the theme that were assigned to each of them. There were very few disagreements, and they were resolved through discussions until consensus was reached.

To answer the next three research questions, discourse analysis (

McVittie & McKinlay, 2023) was conducted on each challenge-related segment, guided by the following questions: Was there a connection between the challenges and the participants’ PSD? (Second research question). Who responded when the challenge was presented—a facilitator or a participant? What did they suggest? Did their responses involve emotional support, different conceptualizations or courses of action? (Third research question). The analysis followed the chronological order of the meetings, as well as the order of the segments within meetings to identify how the narration of challenges and the responses they received evolved (Fourth research question).

3. Results

The first phase of the discourse analysis yielded 113 challenge-related discourse segments. These were divided into four main themes: the relationships with the school’s staff (33 segments), students’ motivation and behavior management (26 segments), teaching practices (23 segments), and technological and bureaucratic procedures (25 segments). The remaining six segments involved personal issues. The first three research questions are addressed as one unit, which are then applied separately to each theme. The results section concludes with a discussion of the fourth research question—how challenge-centered discussions evolved throughout the year.

3.1. Relationships with the School Staff

When beginning to work at the school, three teachers were reluctant to disclose the whole truth about their disabilities and needs, even though some of the disabilities were easily visible and the principals were aware they were hiring teachers with PSD and receiving extra funding.

There’s definitely room [to think about] whether to reveal… how much to reveal, and why…. I could have also lost balance and it’s important that people knew this… I don’t know… I’m constantly dealing with this thing.

(Nathan, meeting 5)

Another challenge faced by four participants was that they did not receive the accommodations they required, and this overshadowed their relationships with their superiors.

I just don’t stop asking for what I need from the vice principal… because they said I would have a girl who is doing voluntary National Service who could help me… and this still hasn’t happened, and every week I ask for this again and again for her to arrange it, so I found my voice.

(Paula, meeting 1)

Both challenges stem directly from the participants’ PSD. In response, the facilitators encouraged the participants to consult with them personally regarding disclosure and promised to intervene on their behalf to ensure they receive the accommodations they need.

Integrating into the school staff might be difficult for every first-year teacher, but it seems that having PSD exacerbates the challenge. Nine participants raised such challenges.

Not long ago, the entire school went on an interesting hiking trail. The whole staff bonded at a restaurant, but because I have difficulty walking, I was unable to participate.

(Adrian, meeting 11)

The participants suggested reminding the organizers of school trips about their accessibility needs, and the facilitators supported the idea. In other cases, participants were exposed to prejudice and hostility.

You enter a new society and need to prove yourself… And you know that you have advantages and disadvantages with these disabilities. And you try to cover them up and hide them. And you try to be nice to everyone… And you take on tons of things [tasks] and you hear… very harsh and very stinging comments. And you need to swallow it and be nice and be service-oriented—to the students, to their parents, and to the staff… [It] becomes very exhausting in the end.

(Sue, meeting 13)

The participants suggested three courses of action. Some recommended remaining silent to avoid losing their job (5). Others proposed working harder to prove their worth, despite the exhaustion (3). Several suggested speaking about their treatment and feelings as individuals with PSD, either with fellow teachers or with the principal (3). An additional participant shared she tried to speak with her principal, but it only made matters worse.

The facilitators provided emotional support by expressing their confidence that the participants would overcome, encouraging their willingness to work hard, though not necessarily harder than anyone else.

Look, … your entry into the school… is certainly not different from any process you’ve done in your lives until today… to the army, national service… and university. All of you here are very educated people… with very diverse life experiences. You’re not bringing only disability to school—you’re bringing this entire world. And the more you continue to expand this world, the system will… see you as diverse and whole people, not as people with disabilities.

(Facilitator 1, meeting 13)

From a professional perspective, two main areas of challenge were identified concerning the participants’ relationships with staff members: receiving guidance from their mentor teachers (4 participants), as exemplified in

Table 2, and accepting critical feedback after they were observed (7 participants). The general approach was to learn from mentors, other available teachers, and from critical feedback without taking offense. However, three participants suggested ignoring comments they perceived as incorrect. The facilitators intervened, encouraging learning and pointing to additional aspects that should be considered.

Paula, I think this is exceptional… how you describe that you… were stressed about her criticizing you, but then you thought that you’re actually learning, and you want to improve. I’m talking to everyone here. It’s not enough that you make the change… It is no less important… to market yourselves, to say that you did something, to say thank you, to say… that it helped.

(Facilitator 2, meeting 4)

First [thing] is… your relationships with the rest of the staff or with whoever is mentoring you. Second, is how you are in the classroom… your pedagogical part… Every such action… is important… How you are within the hierarchy, whether you listen, when do you not do what the hierarchy says… Maybe there’s a price for that afterwards.

(Facilitator 1, meeting 4)

To sum up, the workshop participants encountered the dilemma of fully disclosing their disability even though they had already been hired, and some of their disabilities were easily discernible. They struggled to receive accommodations and integrate with other staff members. This was due to lack of attention to their needs, as well as prejudice and open hostility. These challenges stemming from, or exacerbated by their PSD were faced over and above challenges typical of all beginning teachers. The latter included receiving the mentor teacher’s support and accepting critical feedback from both the mentor teacher and the principal. In addition to emotional support, four strategies were proposed to handle these challenges. These were: remaining silent; compensating for the PSD by working harder than others; self-advocating; and recruiting the facilitators to negotiate with the school principals on the participants’ behalf.

3.2. Student Motivation and Behavior Management

Students’ behavior and motivation were a very significant challenge, which was exacerbated when teachers were assigned to out-of-field, special education classrooms.

I received three very, very challenging classes. I work with a special education class, with students on the autism spectrum, and with a slow pre-matriculation class, although I have no experience whatsoever. I didn’t study special education and didn’t receive any training or tools for these classes. These classes are very, very, very difficult… to the extent that children jumped out of windows during the lesson and threw chairs and took out a ball and started playing ball in the middle of the class.

(Diana, meeting 4)

The participants and the facilitators suggested various courses of action, such as consulting experienced staff members, explicitly expressing their confidence that students could do well and succeed, providing individual assistance to students depending on their behavior during the lessons and more. They all agreed that punishment was undesirable. The facilitators tended to agree with and praise the solutions the participants suggested and then expanded them further. Ann, for example, presented her tolerant attitude towards a restless student.

Ann: I know he tends to get up and walk around, simply because he gets fed up… I tell the child “One minute and you come back” and I check on the clock.

Facilitator 3: Excellent!… Because you’re also a kind of coach. First, you created spaced learning here and prevented the next disruption… Of course, you need to pay attention to whether this minute really helps him, and if it’s realistic. But yes, one minute, two, five. You’re actually starting to train the child to do this and then you can give him the autonomy to start measuring break time for himself.

(Meeting 9)

This response empowers the teacher, praises her proactive approach, provides a theoretical framework for her intuitive actions and explains how to improve this strategy without confrontation. The facilitators also suggested providing additional lessons on teaching special education classes for those who teach out-of-field, but the participants refused.

On some occasions, though, the facilitators felt they needed to object to the participants’ proposals. This happened, for instance, when a participant suggested ignoring students who lack motivation.

Mike: You don’t need to take it personally and get offended. Sometimes, 30 out of 40 students won’t have brought a book or a notebook, and you just need to try… to offer, to say we’re here to teach, to help. Whoever wants it—welcome, and whoever doesn’t, we can’t force them, it’s part of the job.

Facilitator 2: It’s true that not everyone connects… We’re not magicians. However, our role is to try… It’s not about whether they like it [the subject] or not… The story is much more complex. There are those who don’t know how to read, there are those who don’t understand… There are many reasons why people aren’t with you in their hearts… Therefore, you need… to ask the child… not so you can write in his record that he misbehaves, but because you want to know how to help him… and if… you relate to him and build materials that are more adapted to him, slowly you’ll be able to reach more children… Many children have special needs… these needs aren’t always visible. Your role is to try, like a doctor, slowly, to see what’s happening… Come try this… and update us on what happens.

(Meeting 4).

Students’ misbehavior and lack of engagement are severe, yet typical challenges that beginning teachers face. The empathic attitude and good rapport with students that were found among experienced teachers with disabilities (

Neca et al., 2022;

Ware et al., 2022) seem to be in their early stages of consolidation at this point. Throughout the workshop, the facilitators encouraged empathizing with the students on the one hand, and viewing the teachers as largely responsible for improving the students’ misbehavior on the other hand.

3.3. Teaching Practices

This theme includes a wide range of challenges, each mentioned 1–4 times: addressing students’ needs through differentiated instruction; teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge; moral education; infrastructure and workload. Certain challenges were typical of beginning teachers, such as planning an instruction unit or preparing worksheets (pedagogical content knowledge). Others could have challenged even experienced teachers, such as addressing students’ racist statements and views (moral education). A third group of challenges stemmed directly from the teachers’ PSD. Ben, for example, described some of the infrastructure and workload challenges he had due to his visual impairment, and how he handled them through hard work, as well as with the students’ assistance.

I can’t… say, open a workbook in class… [and] flip through [the pages] … Everything needs to be prepared in advance. It’s a lot of work at home, it’s not simple. I need [others] to read me the materials, the pages, the sources, questions, in short, everything, and I go over it with headphones again and again and again…

So, I’m in the classroom, asking [students] to answer by raising their hands, but I can barely see the students, how will I see them raising their hand?… [I decided] to get help from students. Really, every lesson a child sits next to me and tells me who’s raising their hand.

(Ben, meeting 2)

The facilitators provided two types of support. Sometimes, they encouraged the participants to seek other staff members’ help. For example, when students made racist statements, they mentioned the principal, the homeroom teacher, and the education counselor as potential sources of support. More often, they suggested concrete courses of action, sometimes with the help of other participants. For instance, they discussed planning alternatives if the required infrastructure (such as a music room) was unavailable. They were particularly enthusiastic about recruiting students’ help. They also insisted that teachers should not use their accommodations as a means of avoiding the hard work the profession requires.

Mike: For me, because of the health problems I have… it’s very hard to raise my voice, so it’s more comfortable for me [to teach] small groups of 20… So, does that mean… that [when] my hours [the additional funding] run out, no principal will want to employ me?

Facilitator 2: If your voice is weak, you can use a microphone

[…]

Mike: So… it doesn’t matter if we teach a full class or small groups. As long as he [the principal] doesn’t have hours, then it doesn’t matter.

Facilitator 2: Mike, you need to get up in the morning… gather strength and do the work. We’re… giving you a hand to do the work so that they’ll be satisfied, and so that you’ll be satisfied with yourself and say, “Wow, I succeed in working with a whole class with the help of such means and others.”

Facilitator 3: You all know here that ultimately success is measured by meeting standards.

Ruth: If there’s a law in the Ministry of Education that requires them to let us teach and that we have hours, then we don’t need to please [them].

Facilitator 3: The goal isn’t to please. It is to be professional.

(Meeting 2)

In summary, the challenges the participants encountered in their teaching practice stemmed from being inexperienced, as well as from their PSD. The facilitators referred the participants to specific staff members who could help them and suggested concrete courses of action, emphatically encouraging the recruitment of students’ help. Finally, the facilitators attempted to secure accommodations that would enable success, while insisting that teachers not become dependent on exemptions that are temporary or undermine professional standards.

3.4. Technological and Bureaucratic Procedures

The workshop participants unexpectedly struggled with bureaucratic tasks, such as workshop registration and use of technology, including finding materials on the college’s Learning Management System, receiving messages through mobile apps, and creating presentations. These challenges dominated the first meeting, in which seven participants shared they were unsure whether they were properly registered or how to complete registration, and the challenges persisted throughout the workshop until the final meeting. The facilitators responded by using multiple communication channels, providing detailed explanations and individual guidance, referring participants to their school’s pedagogical technology coordinator, and enlisting help from two technologically proficient participants, as in the two examples below.

Facilitator 2: Mark in the chat [your] name and number. If it’s one—then [you] finished the evaluation, two—I’m in the middle of the evaluation, and three—I haven’t started.

Ron: I don’t remember how to do this. I haven’t done this in a long time.

Facilitator 2: At the bottom of the toolbar, you have ‘chat’, click on it and write. Okay?

(Meeting 12)

Most (but not all) of the participants had difficulties operating software and apps, navigating websites, understanding bureaucratic information, and completing registration procedures. The facilitators and technologically proficient participants provided them with concrete and diverse alternative solutions.

3.5. Evolving Patterns in Challenge-Centered Professional Discussions

Throughout the year, the participants’ presentation of their challenges evolved. During the first half of the year, challenges were sometimes “wrapped” in positive statements. “Wrapping” appears to represent a defensive presentation of self-competence that masks ongoing struggles. For example, Ann explained how she transformed a student’s misbehavior through drawing:

In my class there’s a child who simply… doesn’t sit, he’s very jumpy. They tried many ways to get him to sit down and it didn’t work. I said… sit him next to me, and I brought him to a state where he draws during the lesson, but he manages to listen… He’s attentive while drawing, and it’s amazing to see this… He underwent a crazy transformation.

However, when facilitator 2 suggested empowering the student by organizing an exhibition of his drawings, the true challenge was revealed:

I think about it… but he needs to sit next to me… If necessary, I also leave in the middle of class and look for him if he runs away… He takes off in a sprint and disappears in an instant.

(Ann, meeting 4)

Paula’s claim (

Section 3.1) that she “found her voice” is another example of “wrapping,” as she implied successful self-advocacy, whereas all her accommodation requests were actually denied.

“Wrapping” was identified in 10 discourse segments: four in the first meeting, two in the second, and one in each subsequent meeting through to the sixth. This declining pattern suggests that as participants developed trust and psychological safety within the group, they gradually abandoned this face-saving strategy for more authentic disclosure of their experiences.

In nearly all the challenge-related segments, one or two participants interacted with the facilitators. There were only 9 segments that had more than two participants: three took place in meetings 4–6 (with 3 participants in each), and six took place in meetings 10–13 (with 3–7 participants). This tendency suggests that gradually, interactions with the facilitators transitioned into real group conversations typical of CoPs. However, this transformation was not yet completed by the final meeting.

Finally, although most segments had a clearly defined end—often with the challenge presenters explicitly thanking the facilitators— the challenges tended to resurface within the same meeting or in subsequent sessions. For example, Ann’s restless student appeared in both meetings 4 and 9. A similar challenge, of students who find sitting and solving math problems in their notebooks too difficult, was presented by Adrian in meeting 7. The solution he sought—finding the right approach to get each student to study—reflects the same goal he expressed in meeting 4.

Summing up, the data suggests that although seemingly resolved challenges resurfaced throughout the year, teachers’ participation in the workshop discussions about the challenges increased, and their tendency to ‘wrap’ them decreased.

4. Discussion

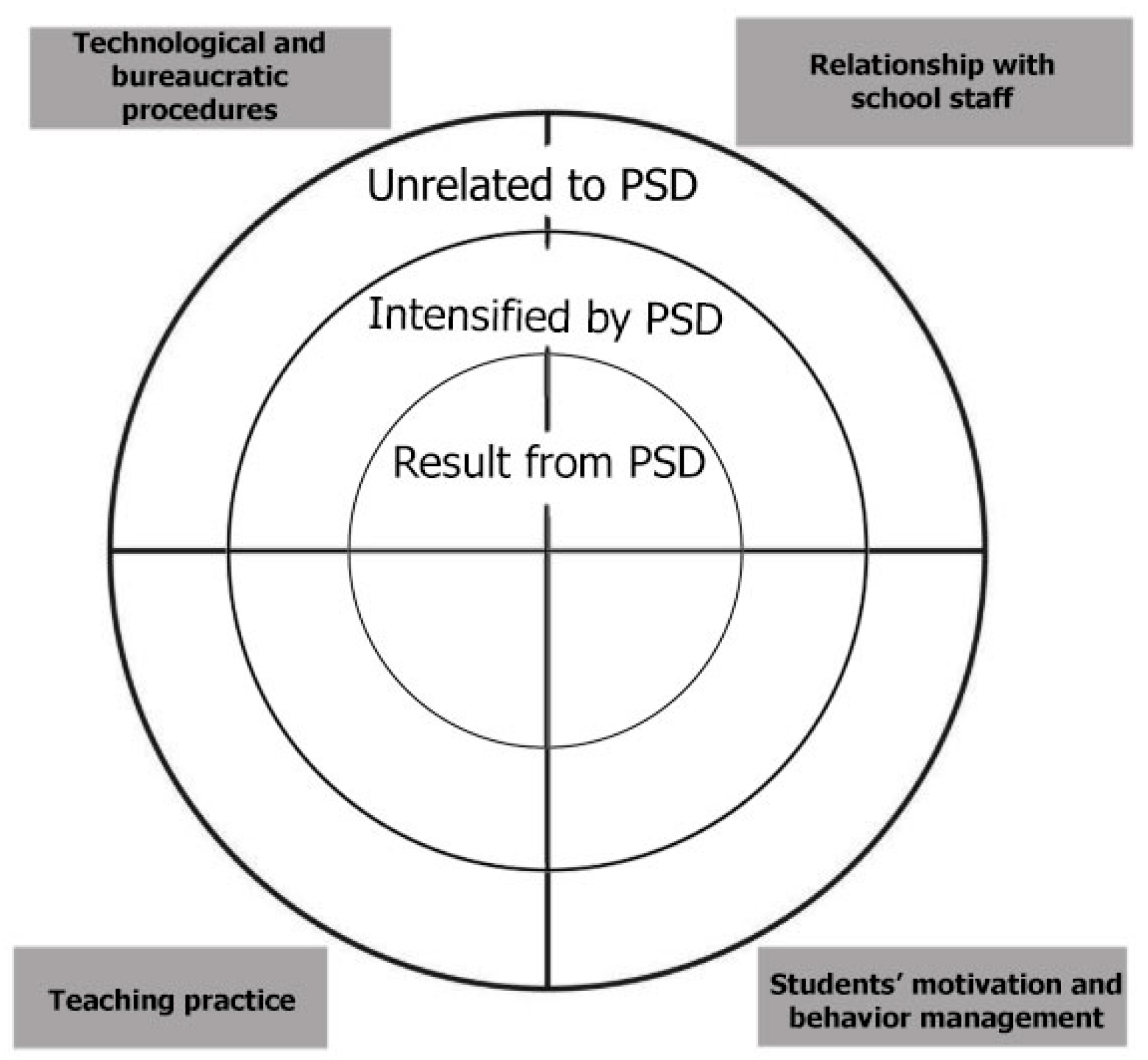

Beginning teachers with PSD who participated in a specialized academic workshop raised challenges in four main areas: relationships with school staff; student motivation and behavior management; teaching practices; and technological and bureaucratic procedures. These challenges demonstrated varying relationships to their PSD—some were unrelated to the disability, others were exacerbated by it, and still others directly resulted from it—creating a complex reality in which the disability intersected with multiple aspects of their induction experience.

The workshop participants responded by sharing their challenges and coping strategies with their peers. The facilitators tailored their responses to specific challenge areas: they offered accessibility interventions; provided emotional support for experiences of prejudice and marginalization; and advised participants to consult them before disclosing their needs. For student misbehavior and lack of engagement they encouraged maintaining an empathetic attitude towards the students, while implementing responsive pedagogical methods. The facilitators suggested theory-based practices and expanded the range of considerations participants should consider while analyzing the challenges and selecting appropriate responses. In addition, they referred the participants to school staff who could be sources of assistance. Regarding technology and bureaucracy, the facilitators provided multiple communication channels and repeated explanations, recognizing that many participants lacked the digital literacy needed to adapt and effectively use digital tools. Over time, the participants became more open in describing their challenges and more engaged in peer discussions. However, challenges that appeared resolved through workshop discussions often resurfaced throughout the year.

Disclosure presents a fundamental dilemma for individuals with disabilities. Honesty about one’s disability can justify the accommodation requests needed to enable professional success, while concealment requires considerable effort, causes mental stress, and negatively affects job performance and social relationships at work. However, disclosure exposes individuals to principals’ prejudice about their professional competencies and reluctance to provide the accommodations, due to concerns about costs, administrative burden, or other teachers’ increased workload. Similarly, colleagues may harbor their own prejudices about teachers with PSD. Refraining from full disclosure and from requesting accommodations, as well as difficulties in receiving accommodations are all well documented in the literature on employees with disabilities (

De Oliveira Neto, 2023;

Elkins, 2025;

Lindsay et al., 2023;

Marathe & Piper, 2025) as well as the literature on teachers with disabilities (

Tal-Alon & Shapira-Lishchinsky, 2019,

2023;

Tomas et al., 2022). The participants of this study had easily recognizable PSD and were accepted by principals who knowingly recruited them. Therefore, it might have been expected that they would not have to confront the disclosure dilemma. Nonetheless, fearing for their employment security, they remained reluctant to disclose the full extent of their disabilities.

Accommodations may be necessary to overcome limitations stemming from the work environment’s design. In this study, some participants who requested accommodations did not receive them. At the same time, accommodations can be a double-edged sword. Temporary and unsustainable accommodations, such as teaching small groups, may ease the transition of beginning teachers with PSD into schools, but can also increase their dependency and reduce their contribution. Consequently, schools may stop hiring teachers with PSD once the special funding ends. This aspect of accommodations has received limited attention in the literature, though similar concerns have been raised about providing accommodations to students with disabilities that may not prepare them for workplace realities (

Hewett et al., 2020;

Lovett, 2021). This finding suggests that the use, as well as the termination, of temporary accommodations needs to be planned.

The workshop facilitators were aware of the complexity surrounding disclosure and requesting accommodations. They therefore preferred to handle these tasks personally and negotiate with schools on the participants’ behalf. They also warned against turning accommodations into exemptions that negatively affect the teachers’ quality of work. However, this approach is insufficient. A more institutionalized function, such as a counselling service, should be established to negotiate disclosure and accommodation provision. This need is justified by the magnitude of the challenges and the growing tendency to recruit individuals with disabilities into education systems (

UNESCO, 2024, p. 99).

Figure 1 schematically represents the interactions between the challenges the participants experienced and their PSD. At the core (innermost circle) of the representation are challenges that directly result from the participants’ PSD. At the periphery (outermost circle) are challenges that are unrelated to PSD. In between (the middle circle), there are challenges exacerbated by PSD to varying extents. For example, having to memorize lesson plans to perfection results from one participant’s visual impairment, whereas participants’ difficulties in social integration into the school staff are exacerbated by their PSD. Students’ lack of motivation appears unrelated to PSD. Such relations were observed in each of the four areas (themes).

The participants’ challenges in three areas—relationships with school staff, student motivation and behavior management, and teaching practices—align with the existing literature on beginning teachers’ experiences (

den Brok et al., 2017;

Clandinin et al., 2015;

Schellings et al., 2023;

Symeonidis et al., 2023;

Zhukova, 2018). The staff’s lack of awareness of the needs of teachers with PSD, prejudice and hostility resulting in social isolation, and the need to “compensate” for disabilities through hard work are documented in the literature on teachers with disabilities (

Miller & Tal-Alon, 2024;

Tal-Alon & Shapira-Lishchinsky, 2019;

Ware et al., 2022;

Wood et al., 2022). However, the confluence and intertwining of these challenges deserve greater attention, particularly within the “teaching practices” theme. For example, memorizing lesson plans increases the already heavy workload typical of beginning teachers. Teacher educators need to map the unique challenges that individuals with PSD may encounter and strive to find solutions. This study contributes to this endeavor by identifying specific challenges, such as lesson planning overload or addressing an entire class without the ability to raise one’s voice. It also contributes to building a repertoire of solutions, including using a microphone or enlisting students’ help to identify raised hands. These solutions can be generalized to other situations, as students can assist in additional ways, such as carrying equipment, and other types of inexpensive equipment may prove helpful.

The frequency and severity of challenges the participants encountered in the “technological and bureaucratic procedures” area were somewhat surprising, as such challenges have received little attention. Nonetheless,

Marathe and Piper (

2025) studied the experiences of visually impaired employees in high-tech companies and found that accessibility measures were often unsuitable and that frequent software upgrades sometimes neglected to include accessibility features, rendering previously accessible software inaccessible. The participants in this study are teachers with varying levels of technological proficiency whose challenges stem from both inaccessibility and insufficient knowledge. Given the increasing role of technology in education, high-tech companies and teacher education institutions must prioritize software and website accessibility. They should test these tools on diverse populations of individuals with disabilities and provide accessible instructions for use. These principles should be extended to online forms and bureaucratic information.

The facilitators adapted their solutions to each domain in both content and form. These solutions ranged from providing direct assistance with technology and bureaucracy to merely expressing confidence that the participants would manage social integration on their own. For teaching practices and students’ motivation and behavior management, the facilitators took a collaborative approach. They built on the participants’ suggestions, developed their ideas further, and connected them to theory. Despite their apparent differences, these approaches stem from the constructivist idea of action within the participants’ “zone of proximal development” (

Vygotsky, 1978). The facilitators started with the participants’ existing knowledge and skills. They then supported further development through learning from both peers and from their own guidance.

The workshop functioned as a CoP designed to support teachers with PSDs’ integration into the education system through sharing, analyzing, and improving their practices (

Wenger, 1998;

Wenger et al., 2023). In such communities, trust-building and sharing typically develop over months. The findings show this process did occur. The participants gradually increased their engagement in discussions. The defensive, face-saving “wrapping” phenomenon gradually ceased, and the participants became more open in their sharing. However, the transformation from facilitator-directed discourse to peer-to-peer conversation had not yet been completed by the end of the academic year. Furthermore, seemingly resolved challenges repeatedly resurfaced. This pattern may reflect an “unbalanced” workshop design (

Sims et al., 2021), as there was no follow-up to track the participants’ implementation of suggested ideas. Consequently, it remains unclear whether the participants attempted to apply workshop ideas, how successful they were, and what contextual adaptations were required. The reduced ability of beginning teachers to adopt new teaching methods (

Zhukova, 2018) may have contributed to this recurrence. The participants’ reluctance to engage in additional guidance for out-of-field special education teaching supports this explanation. Alternatively, the recurrence of challenges could reflect the non-linear character of beginning teachers’ learning (

Schellings et al., 2023).

5. Conclusions

This study identified four main challenge areas for beginning teachers with PSD: relationships with school staff; student motivation and behavior management; teaching practices; and technological and bureaucratic procedures. The facilitators adapted their responses based on the participants’ knowledge and skills, providing theoretical knowledge and emotional support, suggesting courses of action, and offering direct assistance based on the participants’ knowledge and skills. While mutual trust and sharing developed over the year, previously resolved challenges often resurfaced.

This study makes several key contributions. It highlights the challenges that beginning teachers with PSD encounter. It reveals how challenges typical of beginning teachers interweave with those typical of employees with PSD, particularly teachers. Technology-related challenges were specifically highlighted as deserving closer attention. In addition, it revealed the “wrapping” strategy whereby individuals present unresolved challenges as if they were already successfully resolved. Diverse potentially helpful support strategies are presented, among which are CoPs consisting of beginning teachers with PSD. The findings further suggest that the implementation of suggested solutions should be monitored and that support for disclosure and accommodation requests should be institutionalized and planned to counteract their possible negative effects.

The practical implications arising from this study are that teacher educators and mentor teachers supporting beginning teachers with PSD must follow up on how they apply the suggested courses of action in their unique contexts and adapt the solutions based on implementation outcomes. Policymakers need to examine the effectiveness of the support they offer to teachers with PSD and absorbing schools.

These findings and recommendations are generalizable to other contexts to a considerable extent. The existing literature suggests that the challenges beginning teachers with PSD encounter are not unique to Israel. Therefore, many of the solutions would likely be helpful elsewhere. The Ministry of Education’s compulsory induction program, consisting of an academic workshop and a mentor teacher, is unique to Israel. However, the support offered to beginning teachers with PSD could be adapted to initial teacher education programs, where practical experience is typically guided by both mentor teachers and higher education-based teacher educators. Special funding and support for schools that employ teachers with PSD is also uncommon. Nonetheless, lessons learned in this context could be applied in countries planning to increase the recruitment of teachers with PSD.

The findings have several limitations. The study’s scope is very narrow: only one workshop in one country was examined, with a small number of participants and a limited range of disabilities. The prominence of the four challenge areas may have been influenced by the workshop facilitators’ chosen topics rather than solely by the participants’ actual challenges. Only one type of data was collected, and the effectiveness of suggested solutions was not monitored.

Future studies should examine the challenges beginning teachers with PSD encounter in other contexts and countries, including larger cohorts of teachers with a wider range of disabilities. The accessibility of technology and bureaucracy, as well as the “wrapping” phenomenon, should be further explored. The effectiveness of the support strategies identified in this study needs to be examined in multiple contexts, including multiple case studies of CoPs. Finally, longitudinal studies are needed to explore the integration processes of beginning teachers with PSD in schools over longer periods.