Abstract

The increasing number of international students choosing a non-traditional study destination, such as Hungary, underscores the country’s growing appeal in the global higher education landscape. This trend is driven by Hungary’s competitive and quality educational programmes, supportive policies, and rich cultural and historical heritage. This exploratory study examines the cross-cultural experiences of international students studying in the country, drawing on data from a cross-sectional online survey conducted in 2024. Through descriptive and thematic analyses, three principal findings emerged. First, students are attracted to study in Hungary by a combination of instrumental and cultural factors, including the quality and affordability of education, the country’s cultural heritage, and its strategic location in Central Europe. Second, the most significant challenges involve adapting to a different academic culture and overcoming language barriers, both of which hinder everyday communication. Third, difficulties in establishing meaningful connections with Hungarian peers often exacerbate feelings of social distance, thereby limiting the integration of international students. By foregrounding student perspectives in an under-researched, non-traditional study destination context, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of international student mobility beyond the traditional study destinations of Anglophone and Western European settings. The findings offer valuable insights for higher education institutions and policymakers to improve the integration of international students, enhance support structures, and further strengthen Hungary’s position as an attractive and inclusive study destination for global talent.

1. Introduction

Universities have a long history of attracting international students and scholars. While the concept of internationalisation may be prominently associated with contemporary trends in higher education, its historical roots can be traced back to the very establishment of universities in medieval Europe, laying the groundwork for the globalized academic landscape we see today. Institutions like the University of Bologna, established in 1088, followed by the establishment of the University of Paris in 1150 and the University of Oxford in 1167, all served as early centres for international exchange, attracting students and faculty from different countries (Németh & Kajos, 2014; Välimaa, 2019; De Wit & Altbach, 2021; Dávidovics & Németh, 2021; Dávidovics et al., 2024). This longstanding trend of student mobility has demonstrably enriched campuses with diverse perspectives, fostering a dynamic interplay of ideas and cultures that fuels innovation and progress. This trend has gained momentum in the 21st century, as universities prioritize international recruitment to foster campus diversity (Altbach & Knight, 2007; Pozsgai et al., 2012; Németh et al., 2024).

1.1. A Brief Overview of Hungary’s Higher Education System and Internationalisation Trends

Hungary’s higher education system is aligned with the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) and follows the Bologna Process, offering a three-cycle structure of bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral programs. The system encompasses a diverse range of institutions, including research universities, universities of applied sciences, and colleges, both public and private, designed to address various academic and vocational needs. Universities are typically research-oriented, while colleges emphasize practice-based and professional training. In recent decades, Hungary’s higher education landscape has undergone significant structural and organizational changes, often driven by international policy frameworks like the Bologna Process, which some scholars argue has served as a vehicle for deeper systemic restructuring (Pusztai & Szabó, 2008; Kováts, 2018).

In Hungary, the internationalisation of higher education has become an increasingly prominent strategic goal over the past few decades. While earlier efforts focused primarily on student and staff mobility, particularly outbound Erasmus participation, more recent initiatives reflect a broader, more integrated approach to internationalisation. These include the internationalisation of curricula, the expansion of English- and German-taught programmes, increased participation in international research networks, the registration of internationally recognised patents, the recruitment of international faculty, and the implementation of targeted national policies (Lannert & Derényi, 2021). These developments aim not only to enhance institutional quality and relevance but also to improve Hungary’s global visibility and competitiveness in higher education. Internationalisation is increasingly viewed as a transformative process, contributing to institutional innovation, academic quality enhancement, intercultural engagement and the development of globally competent graduates equipped to navigate diverse cultural and professional contexts (M. Smith & Vass, 2017). Hungarian higher education institutions are thus reconfiguring their structures and priorities to better align with global academic standards while responding to local and regional challenges.

Among Hungary’s higher education institutions, the University of Pécs, Corvinus University of Budapest, the University of Debrecen, Semmelweis University and Eötvös Loránd University are particularly prominent in attracting international students. The University of Pécs (UP, 2025), established in 1367, is the oldest university in Hungary. It offers over 80 English-taught and several German-taught degree programs and houses a large international medical faculty. Corvinus University (Corvinus, 2025) is a leading institution for economics, business, and social sciences and has expanded its internationalisation strategy through double-degree programs and English-language curricula, while the University of Debrecen (UD, 2025) is known for its research focus and strong programmes in medicine and science, attracting students from more than 100 countries. Semmelweis University (Semmelweis, 2025), founded in 1769, is Hungary’s top-ranked medical university and a regional leader in health sciences education and research, with international students comprising nearly 40% of its student body. Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE, 2025), established in 1635, is one of Hungary’s most prestigious research universities. Its commitment to a growing international student population is reflected in a broad curriculum delivered in English, German, French, Spanish, and several other languages.

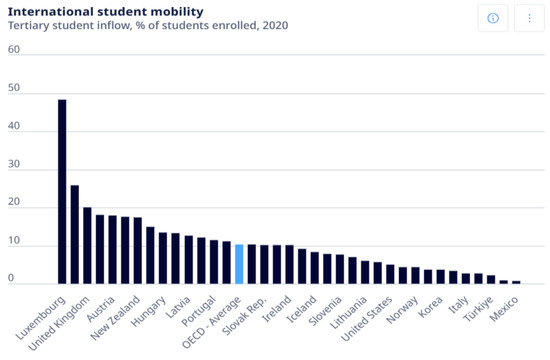

Although Hungary has not historically been a traditional destination for studying, the number of international students in the country has witnessed a steady increase, surging from 11,783 in 2001 to 38,422 in 2019 (Kasza et al., 2021; Császár et al., 2021). This increase can be explained by a confluence of factors, including the Bologna Process and various national policies and initiatives, including the Stipendium Hungaricum and the Hungarian Diaspora Scholarship Programmes aimed at attracting more international students (Pozsgai et al., 2012; Pozsgai & Németh, 2013; Kovacs & Tweneboah, 2020; Tong, 2021; Hild et al., 2025). Reflecting this broader trend, Hungary’s higher education system now features a growing proportion of international students, who made up 13.48% of the student population in 2020—above the OECD average of 10.38% (OECD, 2020), as the graph below illustrates (Figure 1). Among the institutions contributing to this trend are several of the ones mentioned above that have emerged as top choices for international students and have played central roles in Hungary’s internationalisation efforts.

Figure 1.

International student mobility based on data from OECD (2020).

1.2. Research on the Cross-Cultural Adaptation of International Students Studying Abroad in Tertiary Education

Numerous studies have focused on international students’ experiences regarding cross-cultural adaptation from various aspects. Understanding the cultural experiences of international students is essential for higher education institutions aiming to foster an inclusive and supportive environment. Cultural adaptation is a multifaceted process involving the acquisition of intercultural competence, self-awareness, skills, and behaviours necessary for successful integration (Lewthwaite, 1996; Deardorff, 2006; Ruddock & Turner, 2007; Ward et al., 2020). Research indicates that international students often face cultural barriers, including language difficulties, social isolation, and discrimination, which can hinder their academic and social integration (Lewthwaite, 1996; Yan & Berliner, 2011; R. A. Smith & Khawaja, 2011; Faubl et al., 2021). These difficulties can also adversely affect their overall well-being and health, as highlighted by Iorio and Silva (2024) in their study on international students’ experiences in Portugal.

Language proficiency is a critical factor influencing the cultural experiences of international students. Insufficient language skills can lead to communication barriers, academic difficulties, and limited social interactions, exacerbating feelings of isolation and stress (Andrade, 2006; Hessel, 2019; Faubl et al., 2021). Additionally, cultural differences in educational systems and pedagogical approaches can pose significant challenges for international students, requiring them to adapt to new learning styles and expectations (Kennedy, 2002; Dávidovics & Németh, 2021).

Social integration is another vital aspect of the cultural experiences of international students. Developing meaningful relationships with host country students and participating in social activities can enhance their sense of belonging and cultural competence (Kashima & Loh, 2006; Deardorff, 2009; Leask, 2009; Gu et al., 2010; Campbell, 2012; Glass et al., 2014). However, international students often experience difficulties in forming these connections due to cultural differences, language barriers, perceived discrimination, and social segregation (Lee & Rice, 2007; Gareis, 2012).

Moreover, the support systems provided by host institutions play a crucial role in facilitating the cultural adaptation of international students. Universities that offer comprehensive orientation programmes, language support, and culturally sensitive counselling services can significantly enhance the cultural experiences and academic success of international students (Sawir et al., 2008; R. A. Smith & Khawaja, 2011; Chaiyasat, 2020).

Despite the challenges, studying abroad presents international students with valuable opportunities for personal growth, intercultural competence, and global citizenship. Engaging with diverse cultures fosters a broader worldview and enhances students’ ability to navigate an increasingly interconnected world (Lewthwaite, 1996; Deardorff, 2006; Deardorff, 2009; Maharaja, 2018).

While numerous studies have examined the cross-cultural adaptation of international students (Ruddock & Turner, 2007; Long et al., 2009; Ward et al., 2020; Campos et al., 2022), much of this research has concentrated on traditional study destinations of Anglophone and Western European settings. In contrast, relatively little attention has been paid to non-traditional study destinations such as those in the Central and Eastern European (CEE) region. Existing research on the CEE context has begun to shed light on international students’ experiences of integration and adaptation. For example, Przyłęcki (2018), in a study conducted in Poland, identified cultural differences as a major challenge, particularly for students from Arab, African, and Asian backgrounds. More recently, Apsite-Berina et al. (2023) broadened the scope of inquiry by examining the lived experiences of international students in Latvia. The study highlights that international students’ country of origin significantly influences their choice to study in Latvia. While Southeast Asian students are attracted by affordability and English-language programs, students from the former Soviet Union typically do not prioritize Latvia. For European students, low tuition fees, city attractiveness, and programme appeal are key factors. However, language barriers and limited job opportunities hinder their integration into the local labour market.

As the number of international students in CEE countries continues to rise, there is a growing need to better understand the cross-cultural challenges they face and how these may affect their academic performance and social integration. Within this context, Hungary has emerged as an increasingly important yet understudied non-traditional study destination (Kovacs & Kasza, 2018; Erturk & Luu, 2022; Yerken et al., 2022). Kovacs and Kasza (2018) examined the motivations and challenges of international students in Hungary, and they found that while Hungarian universities are increasingly engaged in supporting international student integration, challenges remain, particularly in doctoral programs where support often relies on individual initiative. Language barriers and limited intercultural interaction hinder both academic and social integration. The authors emphasize the need for more structured institutional support, inclusive events, and joint academic or extracurricular activities to foster meaningful connections between Hungarian and international students. Erturk and Luu (2022) also highlight the significance of institutional support mechanisms, particularly language and cultural orientation programs, in facilitating international students’ adjustment. Similarly, Yerken et al. (2022) explored the experiences of Kazakhstani students in Hungarian universities, noting both positive academic outcomes and feelings of social isolation.

Taken together, these studies offer valuable but often fragmented perspectives, frequently limited to specific institutions, disciplines, or national groups. By drawing on a more diverse sample across multiple universities and academic fields, the present study builds upon and extends this emerging body of work, aiming to provide a more comprehensive understanding of international students’ cross-cultural experiences in Hungary as a non-traditional study destination.

This exploratory study forms part of a broader longitudinal research initiative and aims to investigate the cross-cultural adaptation experiences of international students in the Hungarian higher education context. The primary objective is to understand the distinctive nature and impact of cultural exchange within this specific context. By examining these processes over time, the research provides valuable insights into the unique challenges and opportunities that international students encounter culturally, socially and academically. Therefore, the study aims to address the following research questions:

RQ1.

Which aspects of Hungarian culture attract international students to choose Hungary as their study destination?

RQ2.

What are the most significant cultural, social and academic challenges faced by international students during their studies in Hungary?

RQ3.

How do international students perceive the language barrier in Hungary, particularly concerning the Hungarian language and their interactions with their Hungarian peers?

1.3. Theoretical Framework

To provide a theoretical foundation for understanding the cross-cultural experiences of international students in Hungary, this study draws on Young Yun Kim’s Cross-Cultural Adaptation Theory (Kim, 2000, 2005, 2008). Kim conceptualizes adaptation as a dynamic process involving stress, adjustment, and personal growth, whereby individuals gradually develop the communication competence and intercultural awareness necessary to function effectively in a new cultural environment. This integrative theory offers a valuable lens through which to examine how international students navigate cultural and academic challenges, negotiate their identities, and engage with host institutions in a non-traditional study destination, such as Hungary.

Key elements of the theory include the stress–adaptation–growth dynamic, in which individuals experience stress in response to cultural differences, which triggers adaptive responses and leads to personal growth over time. This highlights how challenges encountered in a new cultural environment can become catalysts for transformation rather than barriers to integration. Central to Kim’s framework is the idea of intercultural transformation, whereby individuals, through sustained interaction and communication, internalize certain aspects of the host culture while simultaneously renegotiating their own cultural identity. Such transformation underscores the complexity of international students’ adaptation, as they balance elements of their original identity with new ways of thinking and behaving in the host society. Successful adaptation, according to Kim, also depends on the development of host communication competence, which involves both linguistic proficiency and the broader ability to engage effectively in social interactions. For international students in particular, competence in navigating academic discourse, understanding cultural nuances, and building relationships with local peers and faculty members is a crucial determinant of their adjustment. Finally, Kim emphasizes the role of the environment and individual predisposition in shaping the adaptation process. The receptivity of the host society, the level of institutional and social support available, and the student’s own resilience, motivation, and prior intercultural experience all influence the pace and outcomes of adjustment.

Taken together, Kim’s framework offers a valuable lens for examining how international students in Hungary respond to academic, linguistic, and social challenges in a non-traditional study destination. It helps explain not only the difficulties they face but also the strategies they employ to manage disorientation and uncertainty, and how these experiences contribute to the development of intercultural competence and personal growth (Kim, 2000, 2005, 2008).

2. Materials and Methods

This study utilized a cross-sectional survey design to explore the cultural, social and academic experiences of international students in Hungary. The survey was conducted online from 15 June to 15 July 2024. The questionnaire was developed specifically for this study and included a total of 32 questions, both closed and open-ended. The questions were designed to capture a comprehensive view of the students’ social and cultural experiences in Hungary, as well as their socio-demographic background. It was structured in four main sections:

- (1)

- Socio-demographic background (e.g., age, gender, country of origin, mother tongue, university, field and level of study). Questions included: “What is your mother tongue?” and “What is your field of study?”

- (2)

- Academic experiences (e.g., language of instruction, interaction with teachers and peers, academic challenges, language barrier, perceived academic support). Example questions: “In what language do you study?” and “Have you noticed any language barriers when interacting with Hungarian students?”

- (3)

- Social integration (e.g., friendships with Hungarians, participation in extracurricular activities). Questions included: “How easy has it been for you to make friends with Hungarian students?” “What types of activities do you engage in with Hungarian students? (Select all that apply)?”

- (4)

- Intercultural experiences and adaptation (e.g., perceptions of Hungarian culture, experiences of discrimination, strategies for coping with cultural differences). Sample questions: “What specific aspects of Hungarian culture, if any, attracted you to study in Hungary? (Select all that apply)” and “How difficult have you found it to adapt to the Hungarian culture?”

The open-ended questions provided respondents with the opportunity to narrate both positive experiences and challenges encountered during their academic pursuits in Hungary. Questions included: “Please share any positive stories you have had regarding studying in Hungary.”

Prior to the distribution of the survey, the questionnaire underwent pre-testing in May 2024 with a sample of five international students, comprising two from India, one from Turkey, one from Norway, and one from Pakistan. The pre-test aimed to evaluate the clarity, relevance, and length of the survey. Feedback from the pre-test participants was used to refine the questions, ensuring they were understandable and appropriately framed for the target population.

2.1. Data Collection

The survey was conducted online through the Google Forms platform. Participation was entirely voluntary, with respondents informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any point. Anonymity and confidentiality of their responses were guaranteed. The introduction to the questionnaire provided participants with detailed information regarding the study’s objectives, as well as their rights as respondents. Informed consent was obtained prior to the commencement of the questionnaire through the statement: “I understand the purpose of the questionnaire and hereby consent to participate.” Additionally, assurances of data protection were clearly communicated. The estimated completion time for the survey was approximately 15–20 min.

2.2. Sampling and Participants

A snowball sampling technique was employed to recruit participants. The initial survey link was distributed through various digital platforms, including WhatsApp, Messenger, Instagram, Facebook and email. The primary dissemination started with international student associations and university contacts at several Hungarian universities, and participants were encouraged to forward the survey link to their peers. This method was chosen to maximize reach and ensure a diverse sample of international students. The following inclusion/exclusion criteria were communicated via the above platforms: participants were eligible for inclusion if they were international students currently or formerly enrolled at a Hungarian university, at least 18 years old, and proficient in English, as the survey was administered in English. Exclusion criteria included Hungarian nationals, as the study focused on international students’ experiences, and incomplete survey responses, which were excluded from the final dataset. A total of 232 valid responses were received. Responses were downloaded from Google Forms into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for initial cleaning and coding. Data analysis was conducted using basic statistical methods, focusing on both descriptive and inferential statistics.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Pécs (University of Pécs, 9914–PTE 2024).

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Background

The demographic data presented in Table 1 below indicates that a substantial majority of respondents are female, comprising 60.7% of the sample. The predominant age group is 20–24 years, representing 55.5% of the respondents. The survey received responses from students, demonstrating a diverse array of 58 countries. The most notable representation is from Norway, accounting for 17.5% of the sample. Other significant contributions come from India, Nigeria, Iran, and Pakistan. In contrast, fewer respondents originate from countries such as Algeria, Argentina, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Brazil, Canada, Cape Verde, Chile, China, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, and Egypt, among others.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic background of students.

3.1.1. Mother Tongues

The primary mother tongues reported by respondents include Norwegian (15.7%), Arabic (11.7%), English (8.3%), Russian (5.2%), and Persian (4.8%). The remaining respondents represent diverse linguistic backgrounds, with languages spoken including Albanian, Bengali, Chinese, Igbo, Japanese, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Mongolian, Swahili, Tajik, Turkish, and Urdu, among others. Regarding foreign language proficiency, a significant majority of respondents (89.7%) are fluent in English, followed by Russian (9.4%), French (6.7%), Hindi (6.3%), and German (5.4%).

3.1.2. Studies

Concerning their studies, the majority of respondents are affiliated with the University of Pécs (33.2%), followed by Corvinus University in Budapest (30.1%) and the University of Debrecen (23.6%). A smaller number are enrolled at Semmelweis University (7.4%) and Eötvös Loránd University (2.6%) located in Budapest, with the remaining respondents attending various other universities across the country. In terms of academic levels, 40.7% of respondents are pursuing Bachelor’s degrees, 30.3% are Master’s students, and 23.8% are engaged in Doctoral studies, while the remaining 5.2% are involved in other academic programmes, including non-divided degree programmes. Regarding fields of study, 56.3% are in Medicine, 16.5% in Business, 8.7% in International Relations, and 6.9% in Health Sciences, with the remaining 11.6% studying in diverse disciplines. The distribution of respondents across academic years is as follows: 46.8% are in their first year of study, 20.3% in their second year, 13.4% in their third year, 6.1% in their fourth year, 3.9% in their fifth year, and 4.3% in their sixth year. The remaining participants have already graduated. The primary language of instruction is English (97.4%), with only a small proportion of students studying in Hungarian (1.7%) and German (0.9%).

3.2. Aspects of Hungarian Culture That Attract International Students to Study in the Country

As illustrated by Figure 2, international students are drawn to Hungary by various aspects of its culture, with architectural heritage being the most appealing, cited by 36.6% of respondents. The country’s natural landscape follows closely, attracting 29.7% of students. Additionally, 25% are attracted by the lifestyle in Hungary, and 24.1% find its historical context particularly engaging. Festivals and cultural events also play a significant role, with 20.7% of students noting their importance. Language, while less influential, still attracts 15.1% of respondents.

Figure 2.

Aspects of Hungarian culture that attract international students to study in Hungary.

This result was additionally supported by responses in the open-ended section of the questionnaire:

“Landscape is awesome and beautiful, public transportation is perfect, it’s a small beautiful country that I feel is underrated when it comes to tourism.”

“Pécs is a really lovely city, nice nature, restaurants, and nice weather. Easy to travel with train to close countries as well.”

“Hungarian architecture is very good.”

3.3. Challenges International Students Face Studying in Hungary

Despite all its cultural heritage, richness and diversity, international students face several challenges while studying in Hungary. The most significant issue is the language barrier, reported by 70.3% of students. Academic pressure is also a notable concern, affecting 51.7% of respondents. Cultural differences (33.6%) and social isolation (34.1%) are greatly experienced by students. Financial issues impact 22.4% of students. These statistics are further supported by comments from the students themselves:

“I had no idea what’s going on, because of the Hungarian language.”

“A lot of things are not translated and completely ignore people who don’t speak Hungarian.”

“The beginning is particularly hard with the language and administrative processes.”

“The academic pressure and pressure to pass exams affects the students’ mental health and wellbeing.”

“Loneliness is a thing that can really hit you at times when living/studying abroad.”

Nevertheless, high numbers of students report a positive engagement with faculty and a favourable learning atmosphere, just to quote some comments from the open-ended section:

“People were nice, and the quality of education was superb. University events were amazing.” “Studying is difficult and challenging, but you graduate with a good qualification.”

“I also liked the professors’ input to enhance inclusivity in the class activities, it was incredible, especially in Corvinus where 90% of my classmates are Hungarians.”

3.4. The Language Barrier International Students Face with the Hungarian Language and During Interaction with Hungarian Students

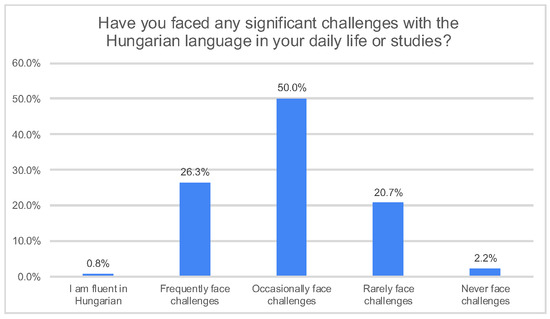

As mentioned above, according to the study, 70.3% of international students identify the language barrier as their primary challenge in Hungary. Although 63.2% of the students have studied Hungarian for at least one year, 76.3% still frequently or occasionally encounter difficulties with the language in their daily lives, as demonstrated by the chart below.

Regarding personal experiences with the Hungarian language, 50% of the students reported occasionally facing challenges (Figure 3); however, they demonstrated a strong commitment to learning the language as a means of better integrating into Hungarian culture. This reflects a proactive approach toward overcoming language barriers and fostering a sense of belonging. As some students noted:

Figure 3.

Challenges faced by international students with the Hungarian language.

“I think international students should make more efforts to integrate themselves into the Hungarian culture or when learning the language, as it was our decision to come to a foreign country.”

“I decided to learn the language as I knew I was going to spend at least four years here and I wanted to feel at home.”

“Language barrier is very significant and makes communication very hard, but I am doing my best to study Hungarian.”

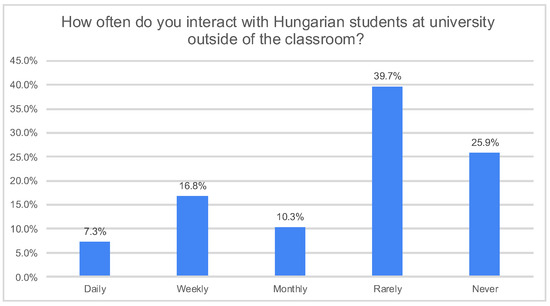

A substantial proportion of international students, 65.6%, report rare or no interaction with Hungarian students outside the classroom, as the graph below demonstrates (Figure 4). Furthermore, two-thirds of the respondents (66%) indicate that forming friendships with Hungarians is particularly challenging.

Figure 4.

Interactions between international and Hungarian students outside the classroom.

This was further corroborated by some of the comments to the open-ended questions:

“Hungarian students always speak Hungarian (even with professors during the classes), and switch to English only if persuasively asked.”

“It is quite hard to build out of class relationships with Hungarian people. They are all very kind and open people, but l think because of how communication and building relationships are different with my culture it is quite challenging for me.”

“In the classroom, Hungarian students would barely talk to internationals and have their special meetings both inside and outside of the university where non Hungarians were not invited.”

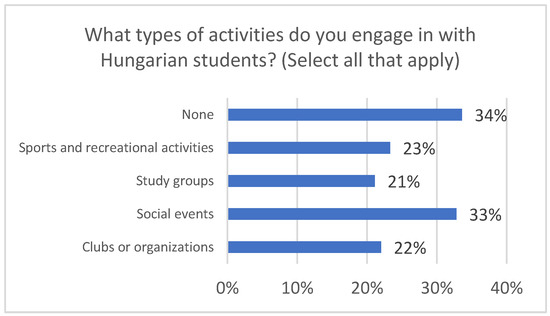

In terms of engaging in activities with Hungarian students (Figure 5), international students report varying levels of interaction across different types of activities. A significant proportion (33.6%) indicates that they are not involved in any joint activities with Hungarian peers. Among those who do participate, 32.8% attend social events, 23.3% engage in sports and recreational activities, 22% are involved in student clubs or organizations, and 21.1% participate in study groups.

Figure 5.

Activities that international students engage in with Hungarian students (multiple responses allowed).

Overall, the results reveal a range of academic and cultural factors that make a non-traditional study destination appealing to international students. At the same time, they shed light on the complex opportunities and challenges these students encounter in their efforts to integrate both socially and academically. Although occasions for interaction with Hungarian peers are present, actual engagement remains limited. These findings offer valuable context for the forthcoming Discussion section to explore this further.

4. Discussion

In recent decades, a huge body of international literature has investigated international students’ experiences regarding cross-cultural adaptation from different angles. Studies have shown that international students often encounter cultural challenges, including language barriers, social isolation, and discrimination, which can obstruct their academic and social integration (Lewthwaite, 1996; Yan & Berliner, 2011; R. A. Smith & Khawaja, 2011; Przyłęcki, 2018; Faubl et al., 2021).

This exploratory study aimed to investigate the cross-cultural experiences of international students in Hungary—a non-traditional study destination—as part of a broader longitudinal research initiative. The study also sought to understand the distinct nature and impact of cultural exchange in this specific context, providing insights into the unique academic and social challenges that international students may encounter during their stay.

Importantly, the five universities most frequently mentioned by participants—the University of Pécs, Corvinus University of Budapest, the University of Debrecen, Semmelweis University and the University of Eötvös Loránd—are among the most internationalised institutions in the country. Their academic profiles, wide range of English- and German-taught programmes, and support services for international students may have played a significant role in shaping respondents’ experiences. These universities have become central actors in Hungary’s internationalisation efforts, not only in terms of student recruitment but also in fostering intercultural engagement and innovation in teaching and research (Lannert & Derényi, 2021; M. Smith & Vass, 2017).

To further enhance the internationalisation of higher education in Hungary and attract a broader range of students from diverse geographic regions, it is essential to understand the key drivers and motivations behind students’ decisions to study abroad. One of the study’s primary research questions focused on identifying culturally attractive aspects of Hungary from the students’ perspectives. Similar to the literature (Apsite-Berina et al., 2023), among the most frequently mentioned attractions were Hungary’s rich cultural and architectural heritage and natural landscape. These features may be particularly compelling for students from distant regions with contrasting geographical and cultural backgrounds. Participants often described Hungary as a small, centrally located, landlocked country in Europe, offering both efficient domestic transportation and easy access to major European destinations. Approximately a quarter of the respondents highlighted the Hungarian lifestyle, its history, and its vibrant cultural scene—including festivals and events—as motivating factors. A notable example is the Sziget Festival, hosted annually in Budapest, which has become one of Europe’s largest music and cultural festivals, attracting over half a million visitors each year, and was awarded the “Best Major European Festival” in 2011 and 2014. (Nagy & Nagy, 2013; Győri, 2019). Such events not only enhance Hungary’s cultural appeal but also contribute to students’ social engagement and cultural immersion. These findings are especially relevant given that the primary demographic for international education consists of young adults. In addition to culture and location, as well as excellent transportation, students also cited favourable weather and climate conditions as attractive features of studying in Hungary. These insights suggest that promotional and recruitment strategies should emphasize these assets to appeal to future cohorts of international students.

Another primary objective of this study was to examine the challenges faced by international students in Hungary. Our findings align closely with those reported in the international literature (Andrade, 2006; Hessel, 2019; Faubl et al., 2021). Most notably, a significant proportion of participants identified the language barrier as a major challenge during their stay. While Hungarian universities offer free language courses to international students to support their integration and daily communication, many participants in this study reported that acquiring proficiency in Hungarian is difficult. Despite this, students expressed a strong commitment to learning the language, recognising it as a vital tool for deeper cultural integration and a sense of belonging. Their responses reflect a proactive attitude toward overcoming linguistic challenges. Importantly, language-related challenges extend beyond the need to master Hungarian. Many international students reported limited meaningful interaction with their Hungarian peers, attributing this not only to linguistic barriers but also to a perceived reluctance among Hungarian students to engage. This hesitancy was often associated with lower self-confidence in using foreign languages compared to their international counterparts. As a result, a majority of respondents reported infrequent or no social interaction with Hungarian students outside academic settings and highlighted significant difficulties in forming friendships. Consequently, despite the availability of social events and opportunities for cross-cultural engagement, a substantial number of international students remain both socially and academically disconnected from the local student community. These findings are cause for concern, particularly given the well-documented link between language proficiency and successful cultural adaptation. Previous research has consistently emphasized that insufficient language skills can hinder academic performance, restrict social interaction, and contribute to feelings of isolation and psychological stress (Lewthwaite, 1996; Andrade, 2006; Hessel, 2019; Faubl et al., 2021). Our study confirms that international students in Hungary are similarly affected by these dynamics, highlighting the need for enhanced language support and cross-cultural engagement initiatives within higher education institutions.

Academic pressure was also identified as a major challenge. Contributing factors may include discrepancies between the level and content of secondary education in students’ home countries and the expectations of the Hungarian higher education system. These findings align with previous studies that highlight differences in educational cultures, teaching methods, and academic attitudes—such as approaches to plagiarism and independent learning—as key sources of difficulty for international students (Kennedy, 2002; Przyłęcki, 2018; Dávidovics & Németh, 2021; Dávidovics et al., 2024). In light of these challenges, harmonizing global secondary education standards and ensuring objective, transparent admission processes may be beneficial. Preparatory courses offered by universities are valuable for bridging educational gaps and easing students’ transitions into tertiary study. From the institutional perspective, university educators should adopt culturally responsive teaching practices that acknowledge students’ diverse learning needs while maintaining academic excellence. Such approaches can support student success and reduce barriers to learning.

Two further challenges frequently cited by participants were cultural differences and social isolation, each reported by approximately one-third of respondents. Research has consistently shown that successful social integration is vital to the overall well-being and cultural competence of international students. Developing meaningful relationships with host country students and participating in social activities can enhance their sense of belonging and cultural competence (Kashima & Loh, 2006; Leask, 2009; Gu et al., 2010; Campbell, 2012; Faubl et al., 2021). However, various factors, including cultural misunderstandings, discrimination, and limited shared activities, often hinder the development of meaningful relationships with host country peers (Lee & Rice, 2007; Gareis, 2012; Przyłęcki, 2018). Przyłęcki (2018) also highlights that cultural differences may contribute to problems during encounters with host students, and the lack of shared classes and other activities may build further barriers in communication between them.

These findings resonate with Kim’s (2000, 2005, 2008) Cross-Cultural Adaptation Theory, which conceptualizes adaptation as a dynamic and ongoing process driven by stress, adaptation, and growth. According to Kim, individuals undergoing intercultural transitions experience psychological and social stress, which in turn stimulates internal adaptation and transformation. The challenges faced by international students, such as social isolation, cultural differences, and communication barriers, can thus be seen not only as obstacles but also as catalysts for intercultural growth. However, this process is highly dependent on the extent of social support and opportunities for meaningful interaction with host nationals, as well as institutional structures that facilitate inclusion. Kim’s theory underscores the importance of recognising these tensions as part of a broader adaptive process that, when supported appropriately, can lead to greater intercultural competence and personal development.

Overall, the findings of the present study underscore the dual nature of Hungary’s appeal and the obstacles that students encounter during their academic tenure in the country. Although they find the system to be quite challenging, they consistently express appreciation for the cultural and architectural heritage, the quality of education and the overall academic environment, as well as for the vibrant cultural life of Hungarian cities and the cultural programmes and atmosphere provided by the Hungarian universities. As higher education institutions continue to attract students from diverse cultural backgrounds, it is imperative to understand their cultural experiences to promote their academic and social success. These cross-cultural interactions are a complex interplay of language proficiency, social integration, and institutional support. Addressing the challenges and leveraging the opportunities associated with these experiences is essential for fostering an inclusive and supportive environment in higher education institutions. Although challenges may arise, international students gain significant benefits from studying abroad, including enhanced personal development, improved intercultural competence, and a stronger sense of global citizenship. Interactions with diverse cultures foster a more expansive worldview and better prepare students to thrive in an increasingly interconnected world (Deardorff, 2006; Deardorff, 2009; Maharaja, 2018; Marek et al., 2020; Marek & Németh, 2020; Németh et al., 2022). Furthermore, the findings contribute to the development of more effective strategies for enhancing academic and social integration, ultimately fostering positive cross-cultural experiences. In addition to improving overall support for international students, this study aims to shed light on the long-term outcomes of their experiences, particularly concerning employability within Hungary and in the global job market.

4.1. Future Research Directions

While this study focuses on cultural, social and academic integration and barriers, future research could explore the impact of these challenges on students’ well-being, mental health and academic performance in more detail. Further studies might also investigate the long-term outcomes of international students in Hungary, such as their employment prospects and retention rates after graduation. Understanding these trends could provide insights into how well Hungary is preparing its international students for global career opportunities and whether the country retains any of the talent it attracts through its universities.

4.2. Limitations

While it is an exploratory study of international students’ cross-cultural and academic experiences in Hungary, there are some limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the findings. The use of a snowball sampling method may limit the generalizability of the results, as the sample may not be representative of the entire population of international students in Hungary. Although efforts were made to reach all major universities in the country, student participation was uneven, resulting in higher representation from certain institutions. The questionnaire was administered in English, which may have influenced responses from non-native English speakers, potentially leading to misunderstandings or less nuanced answers due to language barriers. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable preliminary insights into the cultural experiences of international students studying in a non-traditional destination, which can serve as the basis of future, more extensive research.

5. Conclusions

The growing number of international students globally, including those choosing non-traditional study destinations, such as Hungary, reflects the nation’s rising appeal as an academic destination. This trend underscores not only Hungary’s competitive educational programmes but also its supportive policies tailored to attract international students. With its rich cultural, historical and educational heritage, as well as geographical location, Hungary offers a distinctive environment for students from around the world. Hungary’s ongoing internationalisation efforts, alongside its evolving role as a global academic hub, position the country as a promising destination for higher education. By addressing the challenges identified in this study, Hungary can further solidify its reputation as an attractive educational landscape, continuing to draw global talent and strengthening its position on the international academic stage. Therefore, this research contributes to the broader discussion on international student mobility by examining a less-explored region and providing insights into how Hungary, as an emerging destination, can enhance the experience of its growing international student population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.N. and A.S.; methodology: T.N., A.S. and B.S.; formal analysis: T.N., A.S., B.S. and E.M.; data curation: T.N., A.S., B.S. and E.M.; visualization: T.N. and A.S.; writing, original draft preparation: T.N.; writing, review and editing: T.N., A.S., B.S. and E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Pécs (University of Pécs, 9914–PTE 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical restrictions implemented to safeguard participant confidentiality and adhere to ethical research standards.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the students whose voluntary participation contributed immensely to the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Altbach, P. G., & Knight, J. (2007). The internationalization of higher education: Motivations and realities. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M. S. (2006). International students in English-speaking universities: Adjustment factors. Journal of Research in International Education, 5(2), 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apsite-Berina, E., Robate, L. D., Berzins, M., Burgmanis, G., & Krisjane, Z. (2023). International student mobility to non-traditional destination countries: Evidence from a host country. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin, 72(2), 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, N. (2012). Promoting intercultural contact on campus: A project to connect and engage international and host students. Journal of Studies in International Education, 16(3), 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J., Pinto, L. H., & Hippler, T. (2022). The domains of cross-cultural adjustment: An empirical study with international students. Journal of International Students, 12(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyasat, C. (2020). Overseas students in Thailand: A qualitative study of cross-cultural adjustment of French exchange students in a Thai university context. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 30(8), 1060–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvinus. (2025). Corvinus University. Available online: https://www.uni-corvinus.hu/post/landing-page/about-corvinus-university-of-budapest/?lang=en (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Császár, Z., Teperics, K., & Köves, K. (2021). Nemzetközi hallgatói mobilitás a magyar felsőoktatásban (international student mobility in the Hungarian higher education). Modern Geográfia, 16(2), 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávidovics, A., Makszin, L., & Németh, T. (2024). A national DREEM: Exploring medical and dental students’ perceptions on their learning environment across Hungary. BMC Medical Education, 24(1), 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávidovics, A., & Németh, T. (2021). International students and languages for specific purposes: The results of a study on international students’ perceptions of teaching and learning LSP. Journal of Languages for Specific Purposes, 8, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10(3), 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, D. K. (2009). Connecting international and domestic students. In International students: Strengthening a critical resource (pp. 211–215). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- De Wit, H., & Altbach, P. G. (2021). Internationalization in higher education: Global trends and recommendations for its future. Policy Reviews in Higher Education, 5(1), 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELTE. (2025). Eötvös Lorand University. Available online: https://www.elte.hu/en/about-elte (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Erturk, S., & Luu, L. (2022). Adaptation of Turkish international students in Hungary and the United States: A comparative case study. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 86, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faubl, N., Poto, Z., Marek, E., Birkas, B., Füzesi, Z., & Nemeth, T. (2021). Accepting cultural differences in the integration of foreign medical students. Orvosi Hetilap, 162(25), 978–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gareis, E. (2012). Intercultural friendship: Effects of home and host region. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 5(4), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, C. R., Gómez, E., & Urzua, A. (2014). Recreation, intercultural friendship, and international students’ adaptation to college by region of origin. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 42, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q., Schweisfurth, M., & Day, C. (2010). Learning and growing in a ‘foreign’context: Intercultural experiences of international students. Compare, 40(1), 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Győri, Z. (2019). Between utopia and the marketplace: The case of the sziget festival. In Eastern European popular music in a transnational context: Beyond the borders (pp. 191–211). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hessel, G. (2019). The role of international student interactions in English as a lingua franca in L2 acquisition, L2 motivational development and intercultural learning during study abroad. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 9(3), 495–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hild, G., Dávidovics, A., Warta, V., & Németh, T. (2025). “Video killed the radio star”: Transitioning from an audio-to a video-based exam in hungarian language classes for international medical students. Education Sciences, 15(2), 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio, J. C., & Silva, K. (2024). (Dis)connection between multiculturalism, higher education and health: Experiences of international students in portugal during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences, 14(1), 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashima, E. S., & Loh, E. (2006). International students’ acculturation: Effects of international, conational, and local ties and need for closure. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(4), 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasza, G., Dobos, G., Köves, K., & Császár, Z. M. (2021). International student mobility and COVID-19 students’experiences: The responses of host institutions and countries. In S. J. Trošić, & J. Gordanić (Eds.), International organizations and states’response to COVID-19 (pp. 429–449). Belgrade. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, P. (2002). Learning cultures and learning styles: Myth-understandings about adult (Hong Kong) Chinese learners. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 21(5), 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Y. (2000). Becoming intercultural: An integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. Y. (2005). Adapting to a new culture: An integrative communication theory. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Theorizing about intercultural communication (pp. 375–400). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. Y. (2008). Intercultural personhood: Globalization and a way of being. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32(4), 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, L., & Kasza, G. (2018). Learning to integrate domestic and international students: The Hungarian experience. International Research and Review, 8(1), 26–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs, L., & Tweneboah, G. (2020). Internationalization of hungarian higher education—The contribution of the cooperation with foreign missions. International Research and Review, 10(1), 26–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kováts, G. (2018). The change of organizational structure of higher education institutions in Hungary: A contingency theory analysis. International Review of Social Research, 8(1), 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannert, J., & Derényi, A. (2021). Internationalization in Hungarian higher education. Recent developments and factors of reaching better global visibility. Hungarian Educational Research Journal, 10(4), 346–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, B. (2009). Using formal and informal curricula to improve interactions between home and international students. Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(2), 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. J., & Rice, C. (2007). Welcome to America? International student perceptions of discrimination. Higher Education, 53(3), 381–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewthwaite, M. (1996). A study of international students’ perspectives on cross-cultural adaptation. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 19, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J. H., Yan, W. H., Yang, H. D., & Van Oudenhoven, J. P. (2009). Cross-cultural adaptation of Chinese students in the Netherlands. US-China Education Review, 6(9), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Maharaja, G. (2018). The impact of study abroad on college students’ intercultural competence and personal development. International Research and Review, 7(2), 18–41. [Google Scholar]

- Marek, E., Faubl, N., & Németh, T. (2020). Intercultural competence of medical students in Hungary. Intercultural Communication Studies, 29(1), 22–47. [Google Scholar]

- Marek, E., & Németh, T. (2020). Intercultural competence in healthcare. Orvosi Hetilap, 161(32), 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, A., & Nagy, H. (2013). The importance of festival tourism in the economic development of Hungary. Visegrad Journal on Bioeconomy and Sustainable Development, 2(2), 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, T., & Kajos, A. (2014). How to develop the intercultural competence of Hungarian students. Porta Lingua, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Németh, T., Marek, E., Faubl, N., Sütő, B., Marquette, J., & Hild, G. (2022). Developing intercultural competences for more effective patient care and international medical and research collaborations. Orvosi Hetilap, 163(44), 1743–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, T., Marek, E., Sütő, B., & Hild, G. (2024). Study abroad at home: The impact of a multilingual and multicultural classroom experience on non-native medical students’ English language skills development. Education Sciences, 14(6), 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2020). International student mobility. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/international-student-mobility.html (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Pozsgai, G., Kajos, A., & Németh, T. (2012, October 27/28). The challenges of a multicultural university environment in the area of crisis. Fifth Annual Conference of the University Network of the European Capitals of Culture, Antwerpen, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Pozsgai, G., & Németh, T. (2013). The impact of the European capital of culture title on international student recruitment. In I. Komlosi, & G. Pozsgai (Eds.), Ageing society, ageing culture? Sixth annual conference of the university network of the European capitals of culture (pp. 234–248). University Network of the European Capitals of Culture. [Google Scholar]

- Przyłęcki, P. (2018). International students at the Medical University of Łódź: Adaptation challenges and culture shock experienced in a foreign country. Central and Eastern European Migration Review, 7(2), 209–232. [Google Scholar]

- Pusztai, G., & Szabó, P. C. (2008). The bologna process as a trojan horse: Restructuring higher education in Hungary. European Education, 40(2), 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddock, H. C., & Turner, D. S. (2007). Developing cultural sensitivity: Nursing students’ experiences of a study abroad programme. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 59(4), 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawir, E., Marginson, S., Deumert, A., Nyland, C., & Ramia, G. (2008). Loneliness and international students: An Australian study. Journal of Studies in International Education, 12(2), 148–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmelweis. (2025). Semmelweis University. Available online: https://semmelweis.hu/english/about-semmelweis-university/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Smith, M., & Vass, V. (2017). The relationship between internationalisation, creativity and transformation: A case study of higher education in Hungary. Transformation in Higher Education, 2(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. A., & Khawaja, N. G. (2011). A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(6), 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L. (2021). Higher education internationalization and diplomacy: Successes mixed with challenges. A case study of Hungary’s Stipendium Hungaricum scholarship program. Hungarian Educational Research Journal, 10(4), 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UD. (2025). University of Debrecen. Available online: https://edu.unideb.hu/p/about-ud (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- UP. (2025). University of Pécs. Available online: https://international.pte.hu/university/about-university-pecs (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Välimaa, J. (2019). A history of finnish higher education from the middle ages to the 21st Century. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, C., Bochner, S., & Furnham, A. (2020). The psychology of culture shock. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K., & Berliner, D. C. (2011). Chinese international students in the United States: Demographic trends, motivations, acculturation features and adjustment challenges. Asia Pacific Education Review, 12, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerken, A., Urbán, R., & Nguyen Luu, L. A. (2022). Sociocultural adaptation among university students in Hungary: The case of international students from post-soviet countries. Journal of International Students, 12(4), 933–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).