Too Loud to Ignore: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Hearing Protection in Student Musicians and Ensemble Directors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Is there a significant difference in knowledge of MIHL between high school and university musicians?

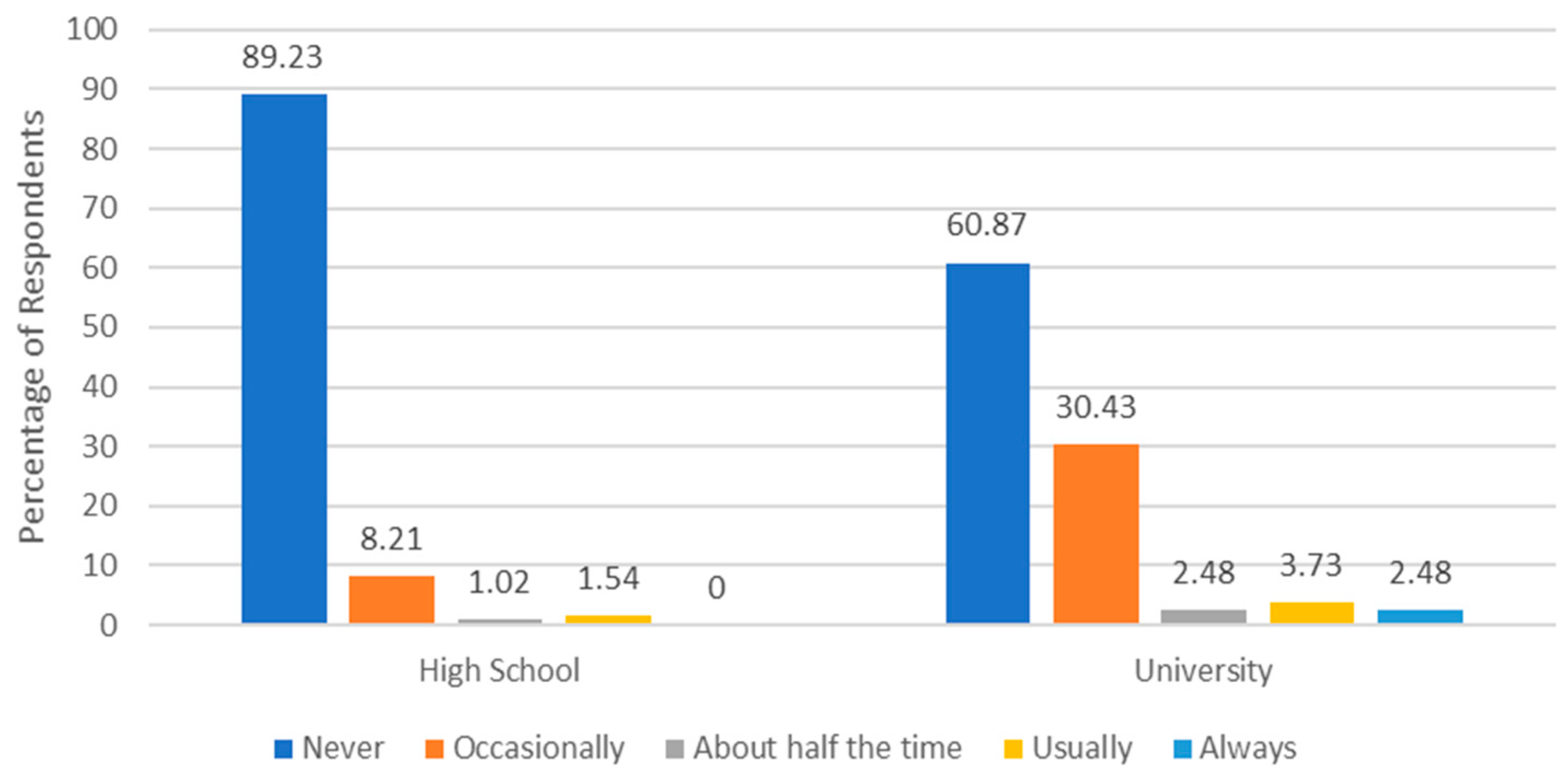

- Is there a significant difference in frequency of hearing protection use between high school and university musicians?

- Does knowledge of MIHL significantly predict use of hearing protection in student musicians?

- Is there a significant difference in use of hearing protection among different instruments?

- Is there a relationship between the number of years of active musical involvement and use of hearing protection?

- What percentage of musicians experiencing auditory symptoms resulting from noise exposure, and what specific symptoms are reported?

- How often do ensemble directors wear HPDs?

- How often do ensemble directors share information about hearing healthcare, and what types of information are shared with students?

3. Results

3.1. Student Musicians

3.2. Ensemble Directors

4. Discussion

- (1)

- It never occurred to me/I never thought of it.

- (2)

- I don’t need it.

- (3)

- I don’t want to.

- (4)

- I can’t afford it.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- High School Student Survey

- What instrument do you play?

- How old are you?

- What different ensembles have you been involved in? (Concert Band, Drum Corps, Orchestra, Marching Band, etc.)? Please List:

- How many years have you been involved with ensemble programs?

- Do you have any hearing loss or disorders? Circle all that apply.

- Hearing Loss

- Tinnitus (Ringing in the ears)

- Hyperacusis (Hearing Sensitivity)

- Loss of clarity

- Diplacusis (Same pitch sounds like two different tones in each ear)

- Ear Pain

- How much do you know about music-induced hearing loss on a scale of 1–5? (1 = nothing at all and 5 = I consider myself well-versed).1 2 3 4 5

- How often has hearing protection been brought up in ensemble rehearsals?NeverOnce or TwicePeriodically/SometimesOftenAlmost every rehearsal

- Are there posters or flyers about hearing protection hung up in your rehearsal space?YesNoI don’t know

- Do you wear hearing protection while you’re rehearsing?NeverOccasionallyAbout half the timeUsuallyAlways

- Do you know where to get hearing protection?YesNo

Appendix B

- College Student Survey

- What is your primary instrument?

- Flute or Piccolo

- Clarinet

- Double Reeds

- Saxophone

- Trumpet

- Trombone

- French Horn

- Tuba or Baritone

- Percussion

- Other

- Are you a current University Student?YesNo

- In what ensembles have you been involved?Concert BandMarching BandOrchestraChamber EnsembleDrum CorpsJazz Band

- Approximately how many years have you been involved in music programs?

- Do you currently experience any of the following symptoms? Choose all that apply.

- Hearing Loss

- Tinnitus (ringing or buzzing in the ear)

- Difficulty understanding speech

- Diplacusis (one tone sounds like two different tones in each ear)

- Ear Pain

- Aural Fullness (Ears feeling full or stopped up)

- None

- What does music-induced hearing loss mean to you?

- How much do you know about music-induced hearing loss on a scale of 1–5(1 = nothing at all and 5 = I consider myself well-versed).1 2 3 4 5

- How often has hearing protection been addressed in your curriculum?NeverIt’s been addressed before, but not regularlyOnce a semesterAt least once a weekEvery rehearsal

- Are there posters, flyers, or other resources about hearing protection in your rehearsal space?YesNoI don’t know

- Do you wear hearing protection during rehearsals?NeverOccasionallyAbout half the timeMost of the timeAlways

- Do you wear hearing protection during performances?NeverOccasionallyAbout half the timeMost of the timeAlways

- If you wear hearing protection, what kind do you wear?Foam EarplugsSilicone Earplugs with filters (Ex. Etymotic or Vibes)Custom EarplugsOtherI don’t wear hearing protection

- Why do you not use hearing protection? (If your answer is “Never” to #11)

- Have you ever had your hearing tested?YesNo

Appendix C

- Director Survey

- How long have you been a music director (in any ensemble)?

- What types of ensembles have you taught in (concert band, marching band, drum corps, orchestra, etc.)? Please list:

- What age of students have you taught? Mark all that apply.Elementary SchoolMiddle SchoolHigh SchoolCollegeAdults

- Were you ever taught about hearing loss in your education?YesNoI don’t remember

- How often do you talk about hearing protection in your program?NeverOnce or TwicePeriodically/SometimesOftenAlmost every rehearsal

- Do you have posters of flyers on hearing protection in your rehearsal space?YesNo

- Do you provide ear plugs for your musicians?YesNo

- Do you share where your musicians can obtain hearing plugs?YesNo

- How important is hearing protection to you?Extremely importantModerately importantMinimally importantNot at all important

- Do you use your own hearing protection in your own rehearsals?NeverOccasionallyAbout half the timeUsually

- Do you have your students use hearing protection in rehearsals?It is requiredIt is recommendedI don’t mind if they wear themI don’t want them to wear them

- What type of information about hearing protection do you make available for your students?Posters/flyersWebsite linksGuest speakers

- How much do you know about music-induced hearing loss on a scale of 1–5 (1 = nothing at all and 5 = I consider myself well-versed)?1 2 3 4 5

References

- Auchter, M., & Le Prell, C. G. (2014). Hearing loss prevention education using adopt-a-band: Changes in self-reported earplug use in two high school marching bands. American Journal of Audiology, 23(2), 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasco-Magraner, J. S., Marin-Liebana, P., Hurtado-Soler, A., & Botella-Nicolas, A. M. (2025). The impact of the soundscape on university life: Critical music education as a tool for awareness and transformation. Education Sciences, 15(5), 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, A. J., Lass, N. J., Foster, L. B., Poe, J. R., Steinberg, E. L., & Duffle, K. A. (2011). Collegiate musicians’ noise exposure and attitudes on hearing protection. Hearing Review, 18(6), 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Camp, J. E., & Horstman, S. W. (1992). Musician sound exposure during performance of Wagner’s ring cycle. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 7(2), 37–39. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2019). Preventing noise-induced hearing loss. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/noise.html (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Chasin, M. (2006). How loud is that musical instrument? Hearing Review, 13(3), 26. [Google Scholar]

- Chasin, M. (2009). Hearing loss in musicians: Prevention & management. Plural Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Chasin, M. (2014). Hear the music: Hearing loss prevention for musicians. Musicians Clinics of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Eichwald, J., & Scinicariello, F. (2020). Survey of teen noise exposure and efforts to protect hearing at school-united states. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(48), 1822–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzlaff, M., Jecker, R., Muller, A., Riegert, M., Riemenschnitter, C., Wenhart, T., Bucher, K., Kleinjung, T., Veraguth, D., Hildebrandt, H., & Bachinger, D. (2025). Awareness and attitudes towards ear health in classical music students-advancing education and care for professional ear users. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1497674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, E., Testa, M., & Hartnick, C. (2011). Prevalence of noise-induced hearing-threshold shifts and hearing loss among US youths. Pediatrics, 127(1), e39–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killion, M. C. (2012). Factors influencing use of hearing protection by trumpet players. Trends in Amplification, 16(3), 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornisch, M., Barton, A., Park, H., Lowe, R., & Ikuta, T. (2024). Prevalence of hearing loss in college students: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 5(17), 1282929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laitinen, H. (2005). Factors affecting the use of hearing protectors among classical music players. Noise & Health, 7(26), 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, H., & Poulsen, T. (2008). Questionnaire investigation of musicians’ use of hearing protectors, self reported hearing disorders, and their experience of their working environment. International Journal of Audiology, 47(4), 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matei, R., Broad, S., Goldbart, J., & Ginsborg, J. (2018). Health education for musicians. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, M. H., Morata, T. C., & Marques, J. M. (2007). Acceptance of hearing protection aids in members of an instrumental and voice music band. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, 73(6), 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, V. L., Stewart, M., & Lehman, M. (2007). Noise exposure levels for student musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 22(4), 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, N., Batts, S., & Stankovic, K. M. (2023). Noise-induced hearing loss. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(6), 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Association of Music Education. (2007). Health in music education (Position statement). Available online: https://nafme.org/resource/health-in-music-education/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- National Association of Schools of Music (NAMA) & Performing Arts Medicine Association (PAMA). (2011). Basic information on hearing health. Information and recommendations for administrators and faculty in schools of music. Available online: https://nasm.arts-accredit.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/02/1_NASM_PAMA-Admin_and_Faculty_2011Nov.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (1996). Criteria for a recommended standard occupational noise exposure, revised criteria. Available online: www.nonoise.org/library/niosh/criteria.htm (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (1998). Criteria for a recommended standard: Occupational noise exposure—Revised criteria 1998 (Publication No. 98-126). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (NIOSH).

- Neerja, M. (2021). Noise-induced hearing loss clinical presentation: History, physical, causes. disease & conditions. Otolaryngology and Facial Plastic Surgery. Available online: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/857813-clinical (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970. Public law No. 91-596, 84 Stat. 1590. (1970). Available online: https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/oshact/toc (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). (1998). Regulations (Standards—29 CFR) Occupational noise exposure—1910.95. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=standards&p_id=9735 (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Peters, C., Thom, J., McIntyre, E., Winters, M., Teschke, K., & Davies, H. (2005). Noise and hearing loss in musicians. Safety and Health in Arts Production and Entertainment. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, S. L., Shoemaker, J., Mace, S. T., & Hodges, D. A. (2008). Environmental factors in susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss in student musicians. (Report). Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 23(1), 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M. A., Goncalves, S., Neves, P., & Silva, M. V. (2019). Sound exposure of secondary school music students during individual study. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 34(2), 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washnik, N. J., Phillips, S. L., & Teglas, S. (2016). Student’s music exposure: Full-day personal dose measurements. Noise & Health, 18(81), 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Programme for the Prevention of Deafness and Hearing Impairment. (1998). Prevention of noise-induced hearing loss: Report of an informal consultation held at the World Health Organization, Geneva, 28–30 October 1997. World Health Organization. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/65390 (accessed on 29 June 2022).

| Type | Number of Respondents | Percentage of Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Silicone non-custom | 51 | 78.5 |

| Foam | 8 | 12.3 |

| Custom-fit | 2 | 3.1 |

| Other | 4 | 6.1 |

| Instrument | Number of Respondents | Percentage of Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Flute | 45 | 12.6 |

| Clarinet | 52 | 14.6 |

| Double Reeds | 6 | 1.7 |

| Saxophone | 38 | 10.7 |

| Trumpet | 59 | 16.6 |

| Trombone | 31 | 8.7 |

| French Horn | 22 | 6.2 |

| Baritone/Tuba | 39 | 11.0 |

| Percussion | 46 | 12.9 |

| Other | 18 | 5.1 |

| Symptom Reported | Number (Percentage) of High School Respondents | Number (Percentage) of University Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Hearing Loss | 31 (15.9%) | 31 (19.2%) |

| Tinnitus | 54 (27.7%) | 53 (32.9%) |

| Loss of Clarity (HS)/ Difficulty Understanding Speech (University) | 7 (3.6%) | 29(18.0%) |

| Ear Pain/Otalgia | 23 (11.8%) | 22 (13.7%) |

| Aural Fullness/ Ear stopped up * | Not a response option | 28(17.4%) |

| Diplacusis | 2 (1.0%) | 2 (1.2%) |

| Hyperacusis ** | 10 (5.12%) | Not a response option |

| Number of Years Teaching Music | What Age of Students Have You Taught? | Do You Use Your Own Hearing Protection in Rehearsals? | Were You Taught About Hearing Loss in Your Education? | How Often Do You Talk About Hearing Protection in Your Program? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | MS, HS, Adults | Usually | Yes | Often |

| 7 | HS | Never | No | Periodically |

| 10 | MS, HS, College | Never | Yes | Periodically |

| 1 | ES, MS, HS | Never | No | Never |

| 1 | ES, MS, HS, College | Never | Yes | Once or Twice |

| 2 | ES, MS, HS | Never | Yes | Once or Twice |

| 28 | ES, MS, HS, Adults | Occasionally | Yes | Once or Twice |

| 1 | ES | Occasionally | No | Once or Twice |

| 4 | MS | Occasionally | Yes | Once or Twice |

| 15 | ES, MS, HS, College | Occasionally | No | Periodically |

| 6 | MS, HS | Occasionally | Yes | Once or Twice |

| 2 | ES, MS, HS | Occasionally | No | Never |

| 4 | MS, HS | Occasionally | Yes | Once or Twice |

| 16 | MS, HS | Occasionally | No | Once or Twice |

| 22 | ES, MS, HS, Adults | Never | No | Never |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Donald, L.; Flagge, A.G. Too Loud to Ignore: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Hearing Protection in Student Musicians and Ensemble Directors. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111454

Donald L, Flagge AG. Too Loud to Ignore: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Hearing Protection in Student Musicians and Ensemble Directors. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111454

Chicago/Turabian StyleDonald, Lucile, and Ashley G. Flagge. 2025. "Too Loud to Ignore: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Hearing Protection in Student Musicians and Ensemble Directors" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111454

APA StyleDonald, L., & Flagge, A. G. (2025). Too Loud to Ignore: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Hearing Protection in Student Musicians and Ensemble Directors. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111454