1. Introduction

Reading is a complex skill that develops over many years. There has been considerable attention to quality reading instruction in elementary school classrooms, with several models that explain how this complex process unfolds. These range from the Reading Rope (

Scarborough, 2001), the Simple View of Reading (

Hoover & Gough, 1990), and more recently the Active View of Reading (

Duke & Cartwright, 2021). Yet, as

Moje et al. (

2008) note, adolescent literacy is a complex world and one that is fraught with myths and mysteries.

Simply applying effective elementary models of reading instruction to middle and high school organizations has resulted in confusion and frustration for school leaders and educators. Secondary school standards place a significant emphasis on content knowledge learning, leaving comparatively little room for dedicated time for reading instruction in classrooms. Further, this decade has witnessed critical changes in government policy regulations regarding reading instruction, especially using approaches labeled as consistent with the “science of reading” movement and resultant promotion or banning of certain approaches (

Cox & Johns-O’Leary, 2024). Added concerns about the immediate as well as lingering impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student reading achievement due to school closures and disrupted learning have brought adolescent reading proficiency to the forefront (e.g.,

Kennedy & Strietholt, 2023;

Kuhfeld et al., 2023). Consequently, middle and high school educators are faced with the challenge of teaching secondary content while fostering the skills necessary to comprehend increasingly complex texts required in their subject areas. The resultant pressure to take immediate action collides with the realities faced by secondary educators: in what form can reading sciences be realistically leveraged, when there is little research available on how this might be accomplished? In fact, the vast majority of studies of this nature focus on elementary schools, which differ significantly in terms of their structure, purpose, and the developmental needs of their students.

The dilemma further deepens for those students who have not yet mastered foundational skills and are now confronted with complex reading materials used in their secondary classrooms. Existing models for secondary students are based on supplemental (Tier 2) or intensive (Tier 3) intervention programs that are primarily focused on multisyllabic word reading, fluency, and comprehension. These supplemental programs are often led by a specialized tutor in a small group or one-to-one setting (

Jun et al., 2010;

Wanzek et al., 2013), yet students report that these interventions are confusing, frustrating, and embarrassing (

Frankel et al., 2021). As

Murnan et al. (

2022) note, reading interventions are not always motivating for students. Although supplemental and intensive interventions offer promising insights into effective approaches for students who struggle with reading, they are difficult to sustain from a cost perspective, time allowances, and human capital, making widespread adoption difficult. Thus, while valuable, they are insufficient in scope for addressing the broader needs of improving reading proficiency for all students. Simply said, reading development is not complete at the end of elementary school, and middle and high school teachers should foster continued reading development for students.

Thus, to systematically promote reading proficiency, educators need a systematized, whole-class, multicomponent approach to adolescent reading that can be delivered by classroom teachers across subject areas such that their efforts amplify intervention efforts. This is not a call to replace supplemental and intensive interventions, but rather to coordinate efforts at the Tier 1 level to better meet the reading needs of the nearly 7 out of 10 adolescents who read at the basic or below basic levels. Crucially, “reading at a third-grade level” has vastly different implications for a ninth-grade student, as opposed to his third-grade sibling. We cannot simply implement multicomponent reading instruction designed for primary students in secondary schools. Further, there is mounting evidence that a business-as-usual approach that has relied on traditional subject-matter knowledge instruction with little attention to the reading skills needed to benefit is not working. The most recent US reading score for twelfth-grade students, as reported by the National Assessment for Educational Progress, notes that it has reached its historic low since 1992 (

National Assessment Governing Board, 2025). If this trend is to be reversed, the field needs to quickly identify effective components to make policy and program decisions that are evidence-based and are practical for classroom teachers to implement.

Conceptual Framework

Multicomponent reading intervention is an evidence-based approach that integrates multiple distinct yet interrelated instructional strategies to enhance reading proficiency. This framework typically includes the explicit teaching of foundational skills such as phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension, each of which contributes to overall reading development. By targeting various components of reading simultaneously, multicomponent instruction addresses the diverse cognitive processes involved in decoding, word recognition, and meaning making. Research conducted at the elementary level supports this approach, as it ensures a more comprehensive development of reading abilities, promoting both accuracy and understanding in diverse educational settings.

In their meta-analysis on multicomponent interventions for adolescent readers,

Scammacca et al. (

2007) found moderate effects for multicomponent models. More recently, the Institute of Education Sciences published findings for improving the reading ability of younger adolescents (grades 4–9) using a multicomponent intervention (

Vaughn et al., 2024). Their findings are as follows:

Build students’ decoding skills so they can read complex multisyllabic words.

Provide purposeful fluency-building activities to help students read effortlessly.

Routinely use a set of comprehension-building practices to help students make sense of the text.

Provide students with opportunities to practice making sense of stretch text (i.e., challenging text) that will expose them to complex ideas and information (p. 3).

A second component of our conceptual framework is the sociocultural approach to reading instruction, which emphasizes the role of social interaction, cultural context, and the reader’s lived experiences in the process of reading (e.g.,

Smagorinsky et al., 2020). For adolescents, this perspective challenges traditional, skills-based models by recognizing that reading is not merely a cognitive task but a socially mediated practice embedded in cultural norms and community values. This approach draws heavily on the work of sky (

Vygotsky, 1978), whose theory of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) underscores the importance of scaffolded learning within a social context. Key principles of sociocultural reading theory include:

Literacy as social practice: The sociocultural approach views reading as a social act shaped by the context in which it occurs. Adolescents bring diverse backgrounds, languages, and cultural identities into the classroom, all of which shape their reading experiences (

Peréz, 1998).

Funds of knowledge: A critical component of the sociocultural perspective is the recognition of students’ culturally developed skills and knowledge that students bring from their homes and communities (

Moll, 2019). Effective reading instruction connects academic content with students’ lived experiences, making reading more relevant and accessible.

Mediated learning through social interaction: Sociocultural theory highlights the role of collaboration and dialogue in reading instruction (

Howe & Abedin, 2013).

Multiliteracies and digital literacies: The sociocultural approach also acknowledges that literacy goes beyond print-based texts. Adolescents engage with multiple forms of media, including digital texts, social media, and visual literacies (

Gee, 1996) and now generative artificial intelligence (

Klarin et al., 2024).

As reading researchers and secondary educators, our lens for this review was influenced by these two conceptual frameworks: the value of what could be learned from multicomponent reading interventions and the crucial nature of sociocultural theories of adolescent reading. We therefore sought to identify components of reading instruction for adolescents that could be implemented and delivered by classroom teachers in a coordinated fashion, such that they foster growth toward proficiency. Thus, our research question was: What components of evidence-based adolescent reading instruction, informed by multicomponent intervention research and sociocultural theories of reading, can classroom teachers integrate into their practice to promote continued growth toward reading proficiency?

2. Methods

The rapid review of literature (RRL) methodology is a streamlined form of systematic review designed to synthesize evidence in a shorter time frame, typically to meet the urgent needs of decision-makers. This methodology was first utilized by health researchers during the COVID-19 pandemic, when it became necessary to make rapid decisions about public health, often in days or weeks (

Fretheim et al., 2020).

Smela et al. (

2023), in their study on the use of RRL as a methodology in medicine, note that “a rapid review is a form of knowledge synthesis that accelerates the process of conducting a traditional systematic review through streamlining or omitting a variety of methods to produce evidence in a resource-efficient manner.” It follows that many of the principles of a full systematic review—such as using explicit and reproducible methods for literature searching, selection, and synthesis—involve certain methodological adjustments to reduce the time required (

Hamel et al., 2021). The key features of an RRL include:

Narrower Scope: Rapid reviews often focus on a more specific research question or a smaller number of outcomes to expedite the review process.

Simplified Search Strategy: The literature search may be limited to fewer databases or more recent studies, and grey literature or unpublished works may be excluded to reduce the volume of material.

Streamlined Study Selection: Fewer reviewers may be involved in the selection and appraisal of studies, and the process of screening and inclusion may be simplified, for example, by focusing on abstracts rather than full-text reviews.

Adapted Quality Assessment: Quality appraisal of studies may be abbreviated, focusing on key indicators of rigor rather than detailed assessments.

Condensed Data Synthesis: The synthesis of evidence is often faster and may focus on high-level patterns or trends rather than in-depth analysis.

For educational researchers and practitioners, an RRL is useful when timely insights are needed to inform policy decisions, curriculum development, or classroom practices. For example, a school district may request a rapid review to evaluate the effectiveness of a particular instructional strategy before implementing it in the next academic year. While an RRL offers a faster turnaround than traditional systematic reviews, it may sacrifice some comprehensiveness and depth, which practitioners need to consider when interpreting the results. However, we argue that the decline of reading proficiency among adolescents is a sufficiently urgent issue that warrants this methodological approach to establish a beachhead for future systematic reviews.

2.1. Procedure

This rapid review of literature was conducted during a seven-week period in spring 2025 and used the EBSCO database, which has a wide reach, indexing 2095 journals. EBSCO is recognized for its high-quality, reliable, and peer-reviewed academic articles and other scholarly resources.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: To ensure recency, we sought to identify studies and reviews of studies that appeared in peer-reviewed journals between 2009 and 2024. Our focus was on studies and reviews of reading practices for students in grades 6–12. Because our interest was in identifying reading practices that could be implemented in the classroom, we focused on those that reflected Tier 1 quality core instruction and Tier 2 (supplemental supports) that were implemented in the classroom by the teacher.

We acknowledge that the issue of the delivery location of Tier 2 supplemental intervention is unresolved, with variability in state policy guidance and within the research literature (

Truckenmiller & Brehmer, 2020). Therefore, Tier 2 studies included in this rapid review of the literature were confined to those that were conducted in the Tier 1 classroom and delivered by the classroom teacher. Making that determination required a careful reading of the individual studies by the first author, as search terms did not effectively screen out studies that occurred outside of the Tier 1 classroom, nor by whom they were delivered.

It was also important to determine what we would exclude in our search. Because of our desire to perform an RRL, we did not include books or book chapters, “grey literature” such as technical reports and policy documents, or dissertations. However, we did not want to narrow our search so much that we would overlook important insights garnered from single-case studies, teacher-directed action research, and quantitative research. We limited the scope of our search to articles published after 2009 to ensure that the research addressed current issues in the lives of adolescents. We limited our search to articles published in English. Importantly, we excluded studies that were implemented in Tier 2 and Tier 3 intensive intervention settings (pulled out from the classroom and delivered by a trained interventionist). In addition, we excluded studies that were not in general education settings, including specialized schools and juvenile justice facilities.

We applied such search terms as “reading instruction” and “adolescent or middle school or high school” to review evidence-based approaches in peer-reviewed journals (see

Figure 1).

We used the Preferred Reporting for Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) as detailed by

Page et al. (

2021). See

Figure 2 for a flowchart of our selection process.

2.2. Analysis

The initial 1135 records returned were further limited using internal search terms in the database for year of publication, language, and peer review. In addition, we refined our search terms using the Boolean “not” feature to further eliminate Tier 3 intensive intervention studies held with individual students, as well as specialized studies of students with reading, learning, behavioral, or cognitive disabilities. The first author then reviewed the remaining 126 documents in our search, eliminating duplications of studies, as well as opinion pieces, those that were conducted outside of general school settings (i.e., after-school programs, incarcerated youth, residential treatment facilities), or did not address reading instruction for adolescents with reading difficulties (i.e., writing instruction, advanced readers).

Kelly et al. (

2022) note that a RRL knowledge synthesis should adhere to core principles designed to ensure that knowledge users can be confident of the findings. The first of their recommendations is to use a protocol and document steps. In this RRL, we used the PRISMA protocol and a trusted database (EBSCO). The steps we followed began with the entire team of researchers reviewing titles and abstracts located by the first author. As a team, we further excluded studies focused on preservice teacher education or in-service professional development. The first author then closely read and analyzed the final 50 published articles. The second author read in their entirety 20% of the 50 final articles (

n = 10). Each study was assigned a number, and we used a random number generator to assign those to be read by the second author, consistent with

Smela et al.’s (

2023) advice on conducting rapid reviews. While we initially expected to find evidence related to common aspects of literacy instruction, such as vocabulary and comprehension, we allowed themes to emerge through an inductive coding process. At the same time, our roles as educators and researchers informed some pre-existing categories, resulting in a combined inductive and deductive approach. These codes were recorded by the first and second authors on a shared spreadsheet and then reviewed and discussed as a full team. This process led to the identification of six major themes essential for supporting adolescents’ continued reading development in middle and high school classrooms.

3. Findings

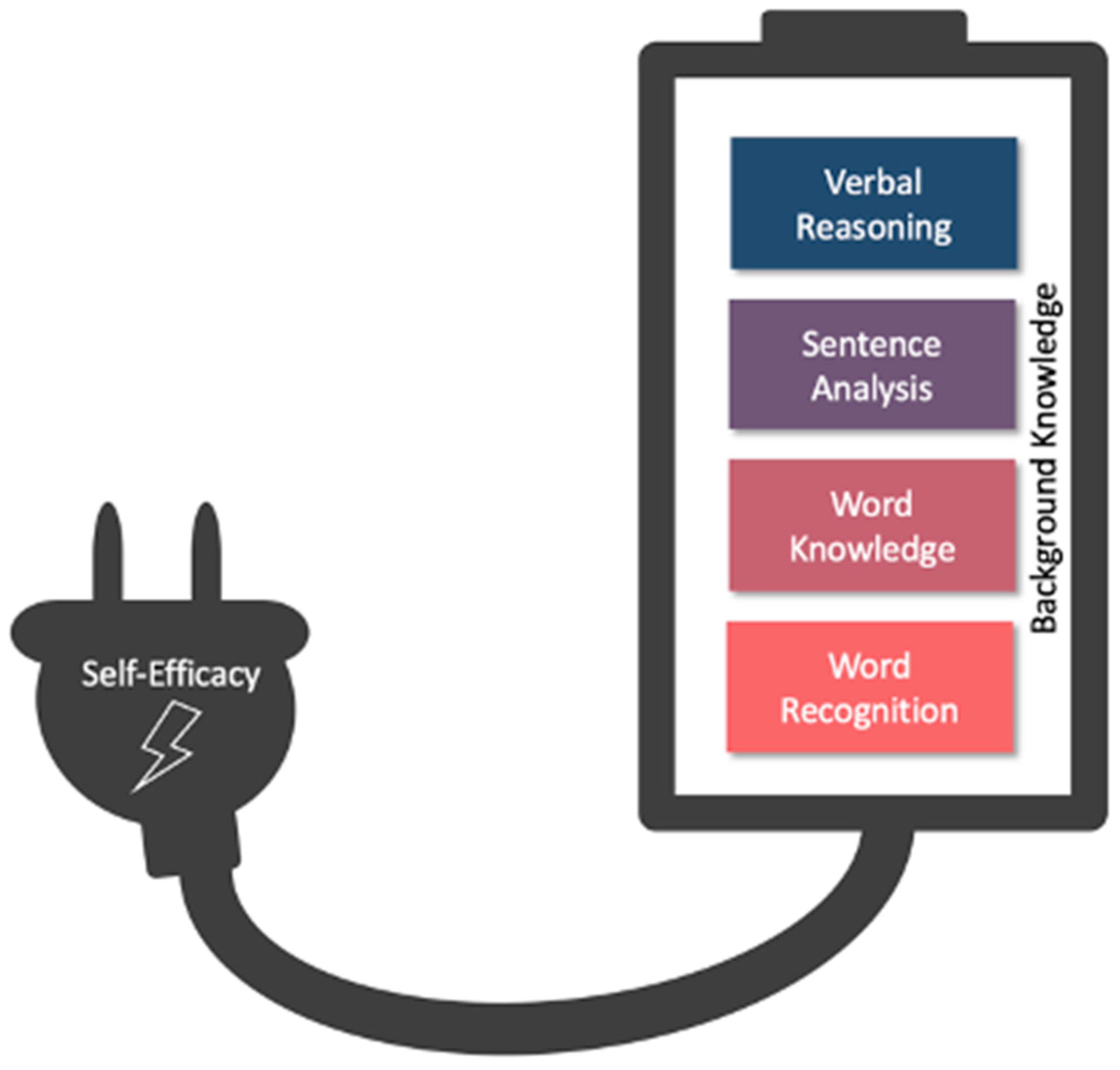

Our rapid review analysis of current adolescent research resulted in the naming of four skill components of adolescent reading instruction, along with two additional overarching dimensions that influence the four components. The authors categorized the studies into four major groups (some studies included more than one aspect of reading instruction): word recognition (n = 14), word knowledge (n = 20), sentence analysis (n = 8), and verbal reasoning (n = 33). Two dimensions that further inform reading research for adolescents were self-efficacy (n = 15) and background knowledge (n = 7).

First, we will discuss two influential dimensions that fuel the four reading skills components, followed by attention to each of these. See

Table 1 for a summary of the study topics by number, percentage, and study authorship. Full citation of the studies can be found in the References section. The number and percentages do not add up to 50 studies or 100% as many were coded in more than one category.

Using the results of our rapid review of the literature, we turned our attention to developing a model of adolescent reading instruction practices that could be implemented by content area teachers. For students who face increased expectations for reading but lack some skills, we propose the following Reading Circuit model (see

Figure 3). This framework is different from other reading initiatives, many of which tacitly assume a degree of reading proficiency. Although multiple reading experiences are important across content, our goal is to enhance the reading proficiency of secondary students through intentional, evidence-based practices implemented across components of the Reading Circuit model. We focus specifically on the reading strategies that teachers can implement to enhance the efficacy of student reading. We fully acknowledge that some students require additional intensive intervention for foundational skills. This model is meant to complement formal reading intervention by emphasizing evidence-based practices within the flow of classroom instruction.

3.1. Powering Reading Through Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is a key driver of learning. Self-efficacy, or the belief in one’s capabilities to succeed in specific tasks, plays a significant role in adolescent reading, particularly for students reading below grade level. Adolescents with high self-efficacy are more likely to persevere through reading challenges, employ strategies that support comprehension, and experience greater achievement, whereas those with low self-efficacy often avoid reading tasks and exhibit diminished progress (

Barber & Klauda, 2020).

These readers often face a dual challenge: not only do they experience difficulties with the mechanical aspects of reading, but they also tend to have lower self-efficacy, which exacerbates their struggles. According to

Kim et al. (

2017), reading approaches that target both skill deficits and motivation, including self-efficacy, are particularly effective in improving reading outcomes. These interventions often involve structured support that gradually reduces in intensity, allowing students to develop confidence in their abilities over time.

One of the key factors in developing self-efficacy for adolescent readers is providing opportunities for successful reading experiences.

Enriquez (

2013) highlights that students’ experiences with reading in the classroom, especially when they feel controlled or constrained, can negatively impact their motivation and self-efficacy. Students need to experience decision-making and autonomy in reading to build positive associations with the activity and gain confidence in their abilities.

Moreover, collaborative learning environments that encourage peer interaction can help foster self-efficacy among struggling readers.

B. W. Johnson and Batchelor (

2018) found that collaborative resistance to digitized instruction in rural middle schools inadvertently fostered a sense of community and self-efficacy among students. This suggests that when students work together, they can build confidence in their reading abilities through shared success and support, even in challenging instructional settings.

Another critical component in promoting self-efficacy is instruction that meets the specific needs of struggling readers.

Wexler et al. (

2015) demonstrated the effectiveness of evidence-based instructional routines in enhancing comprehension, particularly when students are provided with scaffolds tailored to their individual levels of proficiency. Such routines help students incrementally improve their skills, allowing them to experience success, which in turn boosts their self-efficacy. Thus, self-efficacy, as represented in

Figure 3, functions bi-directionally; as reading prowess grows, self-efficacy increases. Likewise, self-efficacy powers future willingness to engage with a challenging task. Findings on the remembered success effect note that when complex academic tasks are interleaved with opportunities for success, middle school students recall their success and are therefore more likely to choose optional challenging tasks (

Finn et al., 2025).

In contrast, if instruction is not aligned with students’ current levels or needs, it can undermine self-efficacy. For example,

Lawrence et al. (

2009) argue that traditional secondary reading instruction often fails to engage struggling readers, leaving them with a sense of inadequacy and further reducing their self-efficacy. This disengagement can lead to a cycle of failure, where low self-efficacy leads to poor performance, which in turn reinforces negative self-perceptions.

Additionally, motivation and self-efficacy are interrelated.

McGeown et al. (

2015) found that adolescents’ reading motivation is closely tied to their self-efficacy beliefs. Those with higher self-efficacy are more likely to view reading as an enjoyable and valuable activity, while students with low self-efficacy often lack intrinsic motivation to engage in reading tasks. Classroom approaches that address both self-efficacy and motivation, such as providing culturally relevant texts and promoting autonomous reading activities, can therefore be particularly impactful.

Effective Tier 1 reading instruction must address both the cognitive and motivational dimensions of reading to build students’ confidence in their abilities. Creating supportive and engaging learning environments where students can experience success and develop autonomy in reading can significantly enhance their self-efficacy and, consequently, their reading achievement (

Guthrie & Klauda, 2014;

Kim et al., 2017;

Wexler et al., 2015). This is the heart of our model for adolescent reading: educators acknowledge the psycho-social factors that inhibit engagement in reading and provide opportunities for students to feel successful. And the evidence on the importance of engagement in reading is strong (

Ivey & Johnston, 2013).

3.2. Powering Reading Through Attention to Background Knowledge

Background knowledge and prior knowledge play a pivotal role in adolescent reading comprehension, especially for students who are reading below grade level. As students progress through grade levels, discipline-specific texts and topics grow increasingly more complex and nuanced, riddled with longer, complex sentences, abstract vocabulary and concepts. In addition, the topical knowledge needed to comprehend increases. When texts have high levels of abstraction, background knowledge is the networked information that we utilize to make meaning while we listen and read. The seven studies reviewed indicate that the ability to draw on prior knowledge not only aids in comprehension but also supports inference-making, critical analysis, and motivation to engage with texts. For adolescents who read below grade level, a lack of background knowledge can hinder these processes, making comprehension more challenging and leading to decreased reading achievement.

Background knowledge is critical for making inferences while reading (

Elbro & Buch-Iversen, 2013). Readers who can connect new information with what they already know are better equipped to make meaning from texts, particularly when explicit details are missing. For struggling adolescent readers, limited background knowledge restricts their ability to make these connections, which can impede their comprehension and lead to misunderstandings. Instructional approaches that explicitly activate and build background knowledge have been shown to improve reading comprehension by helping students bridge gaps between new information and their prior experiences.

Lupo et al. (

2019) further emphasize the importance of prior knowledge in understanding complex texts. Their research highlights how knowledge support, in conjunction with appropriate text difficulty, can significantly impact comprehension outcomes. For adolescents reading below grade level, texts that are too difficult and unfamiliar are especially problematic. Without sufficient prior knowledge to scaffold their understanding, these students are often unable to engage deeply with the material. Providing students with texts that offer some familiarity or introducing key concepts before reading can help mitigate this issue and support comprehension.

Moreover, the role of prior knowledge extends beyond merely understanding the content; it is also essential for critical reading and disciplinary literacy.

Damico et al. (

2009) argue that students’ comprehension in content-area reading, such as social studies, is heavily influenced by their ability to connect the text to broader disciplinary knowledge. In a ninth-grade social studies classroom, students who had greater prior knowledge of the subject matter were able to engage more deeply with the text, asking questions, making connections, and challenging assumptions. In contrast, struggling readers, who often lack this broader disciplinary knowledge, tend to rely on surface-level comprehension strategies, limiting their ability to critically analyze the text.

Importantly, background knowledge influences students’ engagement and motivation to read (

Lawrence et al., 2009). Adolescents who feel confident in their knowledge are more likely to engage with texts and persist through challenges. Conversely, students with gaps in their background knowledge may experience frustration, which can reduce their motivation to read and contribute to a cycle of disengagement and failure. This is particularly problematic for those who already face challenges with decoding and fluency, as they are less likely to persevere when faced with unfamiliar content.

Students’ metacognitive awareness of their own background and prior knowledge is crucial (

O’Reilly et al., 2019). Their research shows that students who are unaware of their knowledge gaps are at a greater disadvantage because they do not realize they need to seek out additional information or clarification. For struggling readers, this lack of awareness can compound comprehension difficulties, as they may not recognize when their understanding is incomplete or inaccurate. Teaching metacognitive strategies that encourage students to reflect on what they know and identify gaps can help them become more effective readers.

Background and prior knowledge are foundational elements of reading comprehension, particularly for adolescents reading below grade level. By drawing on prior knowledge, students are better equipped to make inferences, engage with complex texts, and critically analyze content. Instructional strategies that build and activate background knowledge, provide knowledge support, and develop metacognitive awareness can significantly improve reading outcomes for these students (

Elbro & Buch-Iversen, 2013;

Lupo et al., 2019;

Damico et al., 2009).

3.3. Components of Adolescent Reading Instruction: Word Recognition

Word recognition is a foundational skill for reading comprehension, particularly for adolescents reading below grade level. The 14 studies reviewed consistently show that difficulties with word recognition impede reading fluency, which in turn limits comprehension and overall reading achievement (

García & Cain, 2014). Instructional approaches that focus on improving word recognition are essential for supporting below-grade-level readers in the classroom, especially to complement targeted interventions these students may be participating in at other times during the school day.

Joseph and Schisler (

2009) argue that explicit instruction in phonics and decoding remains necessary for older students who have not yet mastered basic word recognition. Adolescents who struggle with reading frequently have gaps in their foundational skills, making it difficult for them to access grade-level texts. This group benefits from direct instruction in word-reading strategies, such as phoneme segmentation and blending, which helps to build automaticity in recognizing words.

Several studies emphasize the importance of fluency development as part of word recognition instruction.

Paige et al. (

2012) highlight the role of prosody, or the expressiveness with which one reads, in developing fluent reading. Adolescents who are taught to read with attention to pacing, intonation, and rhythm demonstrate improved comprehension, as fluency serves as a bridge between word recognition and text understanding. Instruction that combines word recognition with fluency practice, such as repeated reading or guided oral reading, is particularly effective for older readers (

Kuhn & Schwanenflugel, 2019).

Moreover, integrating word recognition instruction with comprehension-focused activities can enhance learning outcomes and fit within a secondary teacher’s reading routines.

Wexler et al. (

2015) found that evidence-based instructional routines that combine decoding practice with comprehension strategies, such as summarizing or questioning, help students transfer their word-reading skills to broader literacy tasks. This approach allows struggling readers to see the immediate relevance of word recognition to overall reading success.

Effective instruction for improving word recognition in adolescent readers below grade level involves explicit, systematic phonics instruction, often accomplished as part of a targeted intervention. However, these concepts can be coupled with fluency practice and integrated with comprehension activities in the secondary classroom. These strategies not only improve decoding but also enhance reading fluency and comprehension, providing struggling readers with the skills they need to succeed (

Joseph & Schisler, 2009;

Paige et al., 2012;

Wexler et al., 2015).

3.4. Components of Adolescent Reading Instruction: Word Knowledge

Word knowledge, including vocabulary and morphological awareness, is a critical factor in adolescent reading, particularly for adolescents reading below grade level. The ability to recognize, understand, and use words effectively contributes significantly to reading comprehension, and students with underdeveloped word knowledge often struggle to make meaning from text. Instructional approaches that target word knowledge are essential for improving reading outcomes in these students. Fully 42% (

n = 21) of the studies reviewed discussed elements of words as tools, suggesting that teaching students how to use words functionally in various contexts can enhance both vocabulary retention and reading comprehension (

Nagy et al., 2012). Instruction that encourages students to actively use new words in writing and discussion promotes deeper understanding and helps transfer word knowledge from isolated exercises to more meaningful, real-world applications.

One effective instructional approach focuses on explicit vocabulary instruction.

Lesaux et al. (

2010) emphasize the importance of teaching academic vocabulary in a systematic and structured way, particularly for linguistically diverse students. Academic vocabulary refers to the specialized language used in content areas like science and history, which is often unfamiliar to below-grade-level readers. By explicitly teaching these words, students are better equipped to understand complex texts and improve their overall reading comprehension.

In addition to vocabulary instruction, morphological analysis is an important strategy for helping students decode and understand multisyllabic words.

Bhattacharya (

2020) argues that teaching adolescents to break down words into their component parts—such as prefixes, roots, and suffixes—helps struggling readers improve their word recognition and comprehension skills. This approach is especially beneficial for older readers, as it provides them with tools to decode unfamiliar words more independently, reducing their reliance on memorization.

Berkeley et al. (

2012) also highlight the benefits of supplemental reading instruction that incorporates word knowledge activities. Their study found that at-risk middle school readers made significant gains when they were provided with additional instruction focused on vocabulary and word recognition strategies. This kind of targeted instruction, delivered in small needs-based groups, allows for specific attention and practice, which is crucial for students reading below grade level. These strategies not only improve word knowledge but also enhance overall reading comprehension, supporting students in becoming more proficient and confident readers (

Elleman et al., 2019;

Goldman et al., 2016;

Hall et al., 2017).

3.5. Components of Adolescent Reading Instruction: Sentence Analysis

Sentence analysis plays a vital role in improving reading comprehension for adolescents reading below grade level, as it enhances syntactic awareness and helps students grasp complex sentence structures. Instructional approaches that focus on teaching sentence analysis, particularly syntactic awareness and syntactic knowledge, can significantly improve reading outcomes for struggling readers (

Brimo et al., 2017). Syntactic awareness, the ability to understand and manipulate sentence structures, is closely linked to reading comprehension. Adolescents who struggle with sentence analysis often find it difficult to comprehend texts because they fail to grasp the relationships between words and phrases within sentences (

Brimo et al., 2017). Therefore, teaching sentence analysis can help these students deconstruct sentences, identify key grammatical components, and better understand the meaning conveyed.

Instruction that explicitly focuses on sentence structure and syntax has been shown to improve reading comprehension. For example,

Fang et al. (

2014) advocate for a language-based approach to content-area reading that integrates sentence-level analysis into reading instruction. This approach helps students break down complex academic texts, which are often dense with information and difficult to parse for struggling readers. By analyzing the syntactic structure of these texts, students can better identify main ideas, relationships between concepts, and the overall meaning of the text.

Sentence analysis instruction coupled with scaffolding techniques is especially useful for multilingual learners (

E. M. Johnson, 2019;

E. M. Johnson, 2021). Scaffolds such as sentence starters, model sentences, and structured sentence frames provide students with the support they need to practice analyzing sentence structures while gradually becoming more independent. These scaffolds help students understand how different syntactic structures function and how they contribute to the overall meaning of a text. Such approaches are especially beneficial for students who struggle with more complex sentence forms, such as those found in academic texts.

Additionally, sentence analysis instruction can be integrated with other literacy strategies, such as vocabulary development and comprehension activities.

Nagy et al. (

2012) suggest that teaching students how to use syntactic cues in conjunction with word knowledge can deepen their understanding of texts. By understanding both individual words and how they fit into larger sentence structures, students can approach reading tasks with greater confidence and success.

3.6. Components of Adolescent Reading Instruction: Verbal Reasoning

Verbal reasoning, the ability to infer, analyze, and draw conclusions from language, plays a significant role in adolescent reading comprehension. Our rapid review similarly revealed that 33 studies (66%) described elements of verbal reasoning, especially of complex texts. Instructional approaches that explicitly teach verbal reasoning strategies are key to improving the reading outcomes of these struggling students. Research shows that improving verbal reasoning enhances students’ ability to comprehend complex texts by enabling them to engage in higher-order thinking and make inferences beyond the surface meaning of words (

Barnes et al., 2024;

Fiorella, 2023).

One effective instructional approach to improving verbal reasoning is inferential comprehension instruction.

Barnes et al. (

2024) found that both tutor- and computer-delivered inferential comprehension interventions significantly improved the reading comprehension of middle school students with reading difficulties. These interventions focus on teaching students to go beyond literal interpretation of texts and make connections between ideas, which is essential for understanding more complex texts.

Another strategy that enhances verbal reasoning is close reading protocols, which encourage students to critically analyze and interpret text through multiple readings. Close reading promotes deeper engagement with text by helping students focus on specific passages, make inferences, and explore different layers of meaning (

Fisher & Frey, 2014). This instructional approach is especially beneficial for students reading at the basic or below basic level, as it encourages them to slow down and thoroughly process what they are reading, fostering both comprehension and verbal reasoning skills.

Incorporating verbal reasoning instruction into content-area reading is also important. One study highlighted the effectiveness of teaching students to engage in explanatory modeling, a process that encourages students to use reasoning to explain and justify their understanding of complex scientific or historical texts (

Goldman et al., 2016). This approach improves students’ ability to verbalize their thought processes and connect information across different texts, which is a critical component of verbal reasoning.

Furthermore, comprehension instruction that includes verbal reasoning strategies has been shown to be effective across various grade levels.

Filderman et al. (

2022) conducted a meta-analysis of reading comprehension interventions and found that those emphasizing verbal reasoning skills, such as inferencing and critical analysis, yielded positive results for struggling readers in secondary grades.

4. Discussion

Many adolescent readers have attained only minimal or partial mastery of reading (

NCES, 2023); it is no longer an issue that can be mitigated through supplemental or intensive interventions alone. This rapid review of current peer-reviewed studies of adolescent reading difficulties can inform district and school leaders, instructional coaches, and teachers about the development of a comprehensive instructional initiative that can amplify reading intervention for those students receiving this support. Moreover, it can address some of the needs of those students who are not currently receiving support due to fiscal, human resource, or logistical limitations.

Two comprehensive dimensions for an adolescent reading initiative are self-efficacy and background knowledge. The first forms the core of a multicomponent initiative recognizes that learning is bidirectional and requires active engagement, self-regulation, and academic risk-taking (

Hattie, 2023). The second overarching principle of a multicomponent reading initiative is building background knowledge. Again, the evidence of the impact of knowledge on reading comprehension continues it expand (e.g.,

Elbro & Buch-Iversen, 2013;

Lupo et al., 2019). In fact, an adolescent reading initiative that does not place knowledge building at the core is likely to return diminished results.

With these two dimensions in place, further emphasis on reading skill-building can take root. Reliance on elementary models of reading instruction that are framed as phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension is less practical in secondary classrooms. A middle school social studies teacher, for instance, is going to have a difficult time justifying phonics instruction in their classroom. However, a reading initiative that focuses on word recognition can include practices such as segmenting the syllables of new multisyllabic terms such as amendment and compromise in the context of content instruction. Likewise, the skill components of word knowledge, sentence analysis, and verbal reasoning open the door for content area teachers in English, Mathematics, Science, Social Studies, and the Visual and Performing Arts to integrate authentic reading experiences into their instruction.

Supplemental and intensive interventions have proven to be a lifeline for students with reading difficulties. However, when these interventions are perceived as being removed from the daily life of secondary schools—“someone else’s job”—generalization and transfer of reading skills suffer. Nor is it helpful to return to the days of “every teacher is a reading teacher,” a platitude that is met with resistance and resentment, as it is perceived as diminishing their subject matter expertise. And yet the literacies of reading, writing, speaking, and listening play a role in their curriculum. A multicomponent initiative grounded in adolescent reading research can provide a path forward for leaders looking for a way to coordinate systems of instruction and support, while providing teachers and instructional coaches with a common language for how reading skills can be authentically infused into daily instruction.

5. Conclusions

Reading difficulties are not at the margins of secondary schools; a majority of adolescents are not proficient. This compromises instruction as secondary teachers look for workarounds to substitute for reading, including listening to content being read aloud by the teacher or turning away from print altogether in favor of video and lecture. Yet without opportunities to regularly read complex texts, discussion and writing are negatively impacted. A multicomponent reading initiative that honors the research base of adolescents, the academic challenges of subject matter instruction, and the essential nature of coordinated systems can shine a light on how to strengthen reading for the majority of students whose promise is not yet fulfilled.

5.1. Implications for Policy and Practice

The findings from this rapid review of literature suggest that schools and districts should prioritize developing multicomponent, Tier 1 approaches to adolescent reading that can be implemented across content areas. Instead of relying solely on supplemental interventions or expecting “every teacher to be a reading teacher,” leaders can build programming that integrates reading into existing coursework in authentic ways. For example, secondary teachers can emphasize word recognition through syllable segmentation of discipline-specific vocabulary and embed background knowledge supports to scaffold comprehension of technical texts. Districts can support this shift by providing professional learning that helps teachers in all subjects connect reading strategies to their disciplinary texts, and by adopting a common framework—such as the Reading Circuit model—that emphasizes word recognition, word knowledge, sentence analysis, and verbal reasoning alongside motivational factors like self-efficacy and background knowledge.

A second implication is that programmatic decisions should balance skill instruction with motivational and sociocultural supports that encourage persistence and engagement with complex texts. Schools can promote student self-efficacy by embedding opportunities for successful reading experiences, collaborative learning, and choice in text selection, thereby reducing the disengagement that often comes with remedial-style instruction. At the district level, this means investing in curriculum resources that build disciplinary background knowledge systematically and ensuring that all students encounter stretch texts in ways that are supported rather than avoided. By coordinating reading supports across content areas, districts can amplify the impact of interventions and establish coherent systems that address the needs of the majority of adolescents reading at or below basic levels.

5.2. Limitations of the Study and Future Research

While the rapid review of literature offers a resource-efficient approach to evidence synthesis, it carries inherent methodological limitations. The very features that make a rapid review of literature efficient—streamlined search strategies, simplified screening processes, and at times the omission of quality appraisal—also introduce risks. These modifications can limit the comprehensiveness of the review, increase the possibility of bias, and narrow the scope of evidence considered (

Kelly et al., 2022;

Smela et al., 2023). While a rapid review of the literature is practical when time and resources are constrained, particularly for informing urgent policy or practice decisions, it represents a trade-off between speed and rigor. Therefore, future research should include a meta-analysis of studies related to this topic. In addition, future research should examine the implementation of an embedded multicomponent reading approach in middle and high school classrooms, particularly in exploring not only the effectiveness with students, but also the perspectives of secondary educators on how they promote disciplinary knowledge while strengthening the reading proficiency of their students.