Co-Created Psychosocial Resources to Support the Wellbeing of Children from Military Families: Usability Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

“The risk of intergenerational trauma runs high when children’s needs are not seen and the required services are not put in place to support the child’s psychosocial development.”

Children in Military Families

Family members … can be significantly affected when serving or ex-serving members experience poor mental or physical health. A key question becomes, ‘who is caring for the family?’ … the impact of service and deployment has been detrimental to their wellbeing, particularly their mental health. These families are a vulnerable cohort.

Consistently, we have heard that families feel marginalised and invisible… even though family support is a significant protective factor for the serving or ex-serving member’s health and wellbeing. We have heard of the invisibility of children and families.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

- located in any of the Australian states and territories

- civilian parents within a Defence or veteran family, with children aged 2–8 years,

- early childhood educators or support workers (such as Defence School Mentors) who were supporting children from military families.

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

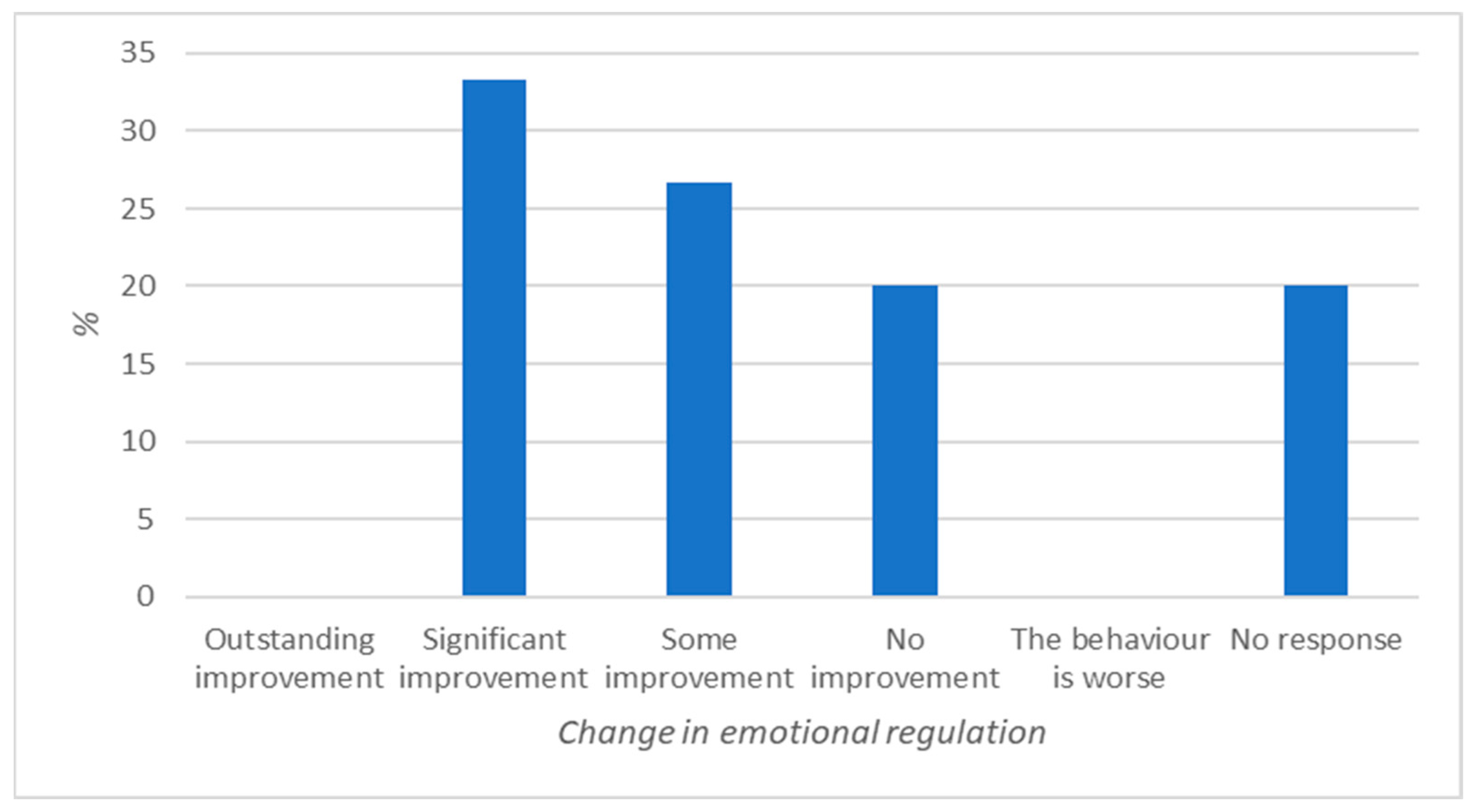

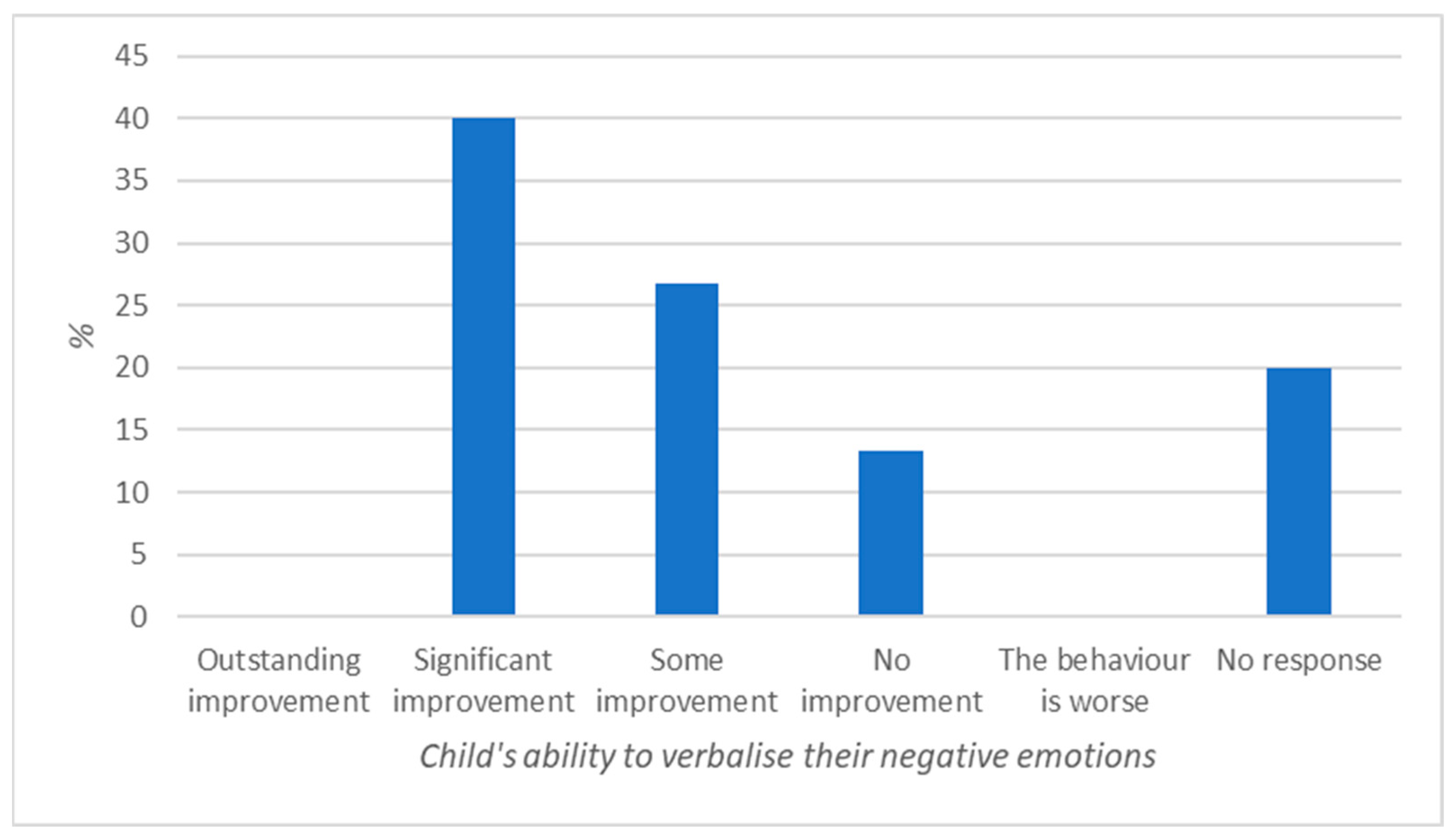

3.1. Quantitative Data

3.2. Qualitative Data

3.2.1. Facilitating Emotional Support and Coping Strategies

Yes, some of the books and apps have reinforced the processes I was already following and even fine tuning some of them.

Families feel supported. Children feel [a] sense of belonging and [can] strengthen their emotional wellbeing.

Yes. When given guidance and age appropriate resources to use, I am able to confidently have difficult discussions with my little ones and those around me.

It gives ownership to children that they are doing something while waiting for the arrival [of an absent parent]. It prepares the child for departure in a systematic manner and reduces the trauma related to separation.

3.2.2. Supporting Military Family Life

For children aged two years old, stories, activities and anything that they create as part of departure, wait and arrival periods affects in easing their separation anxieties and engagement at the service.

[The] 2-year-old [is] responding positively to the change. 3 years old feeling confident in sharing how they feel.

On relocation with a 4-year-old and a 1-year-old, we have used a routine where we could (had to be very flexible on certain days), we read relocation-specific books in the lead up to and while we were in transition accommodation. In settling in we accessed info from apps/online to alleviate/address anxiety around finding new friends. In doing so, I was also able to handle the move better than previous moves, especially with the added stress of two kids.

When working with primary school-aged children, the ECDP has provided relevant resources that link the students’ lived experiences to support materials. This reflection of self has created a connection with resources and therefore worked to build the relationship between Defence School Mentor and students.

3.2.3. Recommending the Resources and Feedback

It is great for students to see their own experiences reflected within resources.

It’s a great resource. Helpful in planning and implementing curriculum.

I think these resources help educators and clinicians outside of defence understand and support defence kids.

As an educator, have a resource coming from research will help in making it relevant to evidence-based and strengths-based service.

Great reference material.

[The] more the merrier. As many as resources can be provided for educators as well as for the families will help in collaborating and partnership with families. This will then support in bringing [the] best learning outcomes for children.

3.2.4. Recommendations for Increased End-User Experience

3.3. Quantitative and Qualitative Findings Combined

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Need for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alsrehan, H. (2025). The social responsibility of universities and its impact on sustainable development towards a future vision. Sustainable Development, 33(5), 6495–6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021). Australian defence force service. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/australian-defence-force-service (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Baulos, A. W., García, J. L., & Heckman, J. J. (2024, September). Perry preschool at 50: What lessons should be drawn and which criticisms ignored? (Working Paper No. 32972). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Blount, R. L., Simons, L. E., Devine, K. A., Jaaniste, T., Cohen, L. L., Chambers, C. T., & Hayutin, L. G. (2008). Evidence-based assessment of coping and stress in pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(9), 1021–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, A., Williams, L., & Goubanova, E. (2022). Sources of risk and resilience among adolescents from military families. Military Behavioral Health, 10(2), 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2022). Interim report of the royal commission into defence and veteran suicide. Available online: https://defenceveteransuicide.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/royal-commission-defence-and-veteran-suicide-interim-report (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Cramm, H., Norris, D., Schwartz, K. D., Tam-Seto, L., Williams, A., & Mahar, A. (2020). Impact of Canadian armed forces veterans’ mental health problems on the family during the military to civilian transition. Military Behavioral Health, 8(2), 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defence Housing Australia. (2025). Housing. Available online: https://www.dha.gov.au/housing (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- DeVoe, E. R., Paris, R., & Acker, M. (2016). Prevention and treatment for parents of young children in military families. In Parenting and children’s resilience in military families (pp. 213–227). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate of People Intelligence and Research. (2020). Australian Defence Force families research 2019. Available online: https://www.defence.gov.au/adf-members-families (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- England, Z., Forbey, J., & Muszynski, M. (2024, April 10). Using research to solve societal problems starts with building connections and making space for young people. Available online: https://theconversation.com/using-research-to-solve-societal-problems-starts-with-building-connections-and-making-space-for-young-people-221834 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Frederick, J., & Siebler, P. (2023). Military children: Unique risks for mental health and wellbeing and implications for school-based social work support. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 92(4), 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, A., Glăveanu, V., & de Saint Laurent, C. (2024). Pragmatism and methodology: Doing research that matters with mixed methods. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, L. K., & Moore, B. A. (2016). Counseling military families: What mental health professionals need to know. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hariton, E., & Locascio, J. J. (2018). Randomised controlled trials—The gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: Randomised controlled trials. BJOG, 125(13), 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, S., Williams, A., Khalid-Khan, S., Reddy, P., Groll, D., Rühland, L., & Cramm, H. (2023). Mental health of Canadian military-connected children: A qualitative study exploring the perspectives of service providers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32(11), 3447–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa, M. S., Hinojosa, R., Condon, J., & Fernandez-Reiss, J. (2022). Child mental health outcomes in military families. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 32(5), 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, P. (2022). Childcare deserts & oases: How accessible is childcare in Australia? Mitchell Institute. Available online: https://www.vu.edu.au/mitchell-institute/early-learning/childcare-deserts-oases-how-accessible-is-childcare-in-australia (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Jamieson, N., Carey, L. B., Jamieson, A., & Maple, M. (2023). Examining the association between moral injury and suicidal behavior in military populations: A systematic review. Journal of Religion and Health, 62(6), 3904–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarden, A., & Roache, A. (2023). What is wellbeing? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohrt, B. A., & Song, S. J. (2018). Who benefits from psychosocial support interventions in humanitarian settings? Lancet Global Health, 6(4), e354–e356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaninen, M., Kulic, N., & Erola, J. (2024). Age of entry into early childhood education and care, literacy and reduction of educational inequality in Nordic countries. European Societies, 26(5), 1333–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, D., Varker, T., Pham, T., Connor, J. O., & Phelps, A. (2017). Reach, accessibility and effectiveness of an online self-guided wellbeing website for the military community. Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health, 25(2), 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonell, G. V., Bhullar, N., & Thorsteinsson, E. B. (2016). Depression, anxiety, and stress in partners of Australian combat veterans and military personnel: A comparison with Australian population norms. PeerJ, 4, e2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maree, J. (2022). The psychosocial development theory of Erik Erikson: Critical overview. In R. Evans, & O. N. Saracho (Eds.), The influence of theorists and pioneers on early childhood education (pp. 119–133). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nassif, T. H., Britt, T. W., & Adler, A. B. (2025). Risk and protective factors associated with adjustment to military relocation: A pilot study. Military Medicine, usaf142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, S., Newman, C., & Lancaster, K. (2019). Qualitative interviewing. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences (pp. 391–410). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neal, C. W., & Mancini, J. A. (2021). Military families’ stressful reintegration, family climate, and their adolescents’ psychosocial health. Journal of Marriage and Family, 83(2), 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormeno, M. D., Roh, Y., Heller, M., Shields, E., Flores-Carrera, A., Greve, M., Hagan, J., Kostrubala, A., & Onasanya, N. (2020). Special concerns in military families. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22(12), 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A. M. H., Contreras-Suárez, D., Zhu, A., Schreurs, N., Measey, M. A., Woolfenden, S., Burley, J., Bryson, H., Efron, D., Rhodes, A., & Goldfeld, S. (2023). Associations between ongoing COVID-19 lockdown and the financial and mental health experiences of Australian families. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M., Johnson, A., Coffey, Y., Fielding, J., Harrington, I., & Bhullar, N. (2023). Parental perceptions of social and emotional well-being of young children from Australian military families. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 31(6), 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M., Sims, M., Johnson, A., Gossner, M., & Thorsteinsson, E. (2025a). Young children’s understanding of military family life: Co-creating educational and therapeutic resources using children’s voices. Family Court Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M., Sims, M., Siebler, P., Gossner, M., & Thorsteinsson, E. B. (2025b). Moving beyond mosaic: Co-creating educational and psychosocial resources using military children’s voices. Educational Sciences, 15, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Sims, M., Johnson, A., Small, E., Gossner, M., & Bhullar, N. (2025c). Social and emotional wellbeing of children from Australian military families: Insight from early childhood educators. Family Court Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiner, B., Gottlieb, D., Rice, K., Forehand, J. A., Snitkin, M., & Watts, B. V. (2022). Evaluating policies to improve access to mental health services in rural areas. The Journal of Rural Health, 38(4), 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebler, P. (2015). ‘Down under’: Support to military families from an Australian perspective. In R. Moelker, M. Andres, G. Bowen, & P. Manigart (Eds.), Military families in war in the 21st century (pp. 287–301). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, E., & Couper, M. P. (2017). Some methodological uses of responses to open questions and other verbatim comments in quantitative surveys. Methods, Data, Analyses, 11(2), 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Spilt, J. L., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2022). Three decades of research on individual teacher-child relationships: A chronological review of prominent attachment-based themes. Frontiers in Education, 7, 920985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiteri, J. (2022). The untapped potential of early childhood education for planetary health: A narrative review. In W. Leal Filho (Ed.), Handbook of human and planetary health (pp. 297–311). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Strader, E., & Smith, M. (2022). Some parents survive and some don’t: The Army and the family as “greedy institutions”. Public Administration Review, 82(3), 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. E., & Seeman, T. E. (1999). Psychosocial resources and the SES–health relationship. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896(1), 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tupper, R., Bureau, J. F., & St-Laurent, D. (2018). Deployment status: A direct or indirect effect on mother–child attachment within a Canadian military context? Infant Mental Health Journal, 39(4), 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, C., Whelan, J., Brimblecombe, J., & Allender, S. (2022). Co-creation, co-design, co-production for public health—A perspective on definition and distinctions. Public Health Research & Practice, 32(2), e3222211. [Google Scholar]

- Veri, S., Muthoni, C., Boyd, A. S., & Wilmoth, M. (2021). A scoping review of the effects of military deployment on reserve component children. Child & Youth Care Forum, 50(4), 743–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Suchodoletz, A., Lee, D. S., Henry, J., Tamang, S., Premachandra, B., & Yoshikawa, H. (2023). Early childhood education and care quality and associations with child outcomes: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 18(5), e0285985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westrupp, E., Greenwood, C., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., Olsson, C., Sciberras, E., Mikocka-Walus, A., Melvin, G., Evans, S., Stokes, M., Wood, A., Karantzas, G., Macdonald, J., Toumbourou, J., Teague, S., Fernando, J., Berkowitz, T., Ling, M., & Youssef, G. (2021). Parent and child mental health trajectories April 2020 to May 2021: Strict lockdown versus no lockdown in Australia. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 56, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodall, K. A., Esquivel, A. P., Powell, T. M., Riviere, L. A., Amoroso, P. J., & Stander, V. A. (2023). Influence of family factors on service members’ decisions to leave the military. Family Relations, 72(3), 1138–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurlinden, T. E., Firmin, M. W., Shell, A. L., & Grammer, H. W. (2021). The lasting effects of growing up in a military-connected home: A qualitative study of college-aged American military kids. Journal of Family Studies, 27(4), 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Activity | Participants |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pre-intervention survey generating quantitative data only | Participant Group 1 = 70 |

| 2 | Online intervention | Engagement not tracked |

| 3 | Post intervention survey including quantitative and qualitative data | Participant Group 2 = 15 |

| Question | Strongly Agree | Partly Agree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Partly Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have an understanding of the experiences of children from Defence families | |||||

| Pre (N = 29) * | 15 (51.7) | 14 (48.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Post (N = 15) | 11 (73.3) | 4 (26.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I have an understanding of the responses of children to military family stressors (e.g., parental deployment, family transitions, frequent relocations and other stressors such as service-related mental health conditions and physical injuries) | |||||

| Pre (N = 70) | 29 (41.4) | 27 (38.6) | 5 (7.1) | 9 (12.9) | 0 |

| Post (N = 15) | 11 (73.3) | 4 (26.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I have experience providing support to Defence families (including parents, extended family and older siblings) | |||||

| Pre (N = 29) * | 14 (48.3) | 10 (34.5) | 1 (3.4) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (6.9) |

| Post (N = 15) | 9 (60.0) | 5 (33.3) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 |

| I feel confident providing emotional support to children from Defence families | |||||

| Pre (N = 70) | 19 (27.1) | 33 (47.2) | 6 (8.6) | 12 (17.1) | 0 |

| Post (N = 15) | 9 (60.0) | 5 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 0 |

| Wellbeing Indicators | Most of the Time | About Half of the Time | Rarely | No Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keeps interested in things | ||||

| Pre (N = 70) | 40 (57.2%) | 23 (32.9%) | 3 (4.3%) | 4 (5.7%) |

| Post (N = 15) | 6 (40%) | 6 (40%) | 0 | 3 (20%) |

| Likes challenges | ||||

| Pre (N = 70) | 25 (35.7%) | 29 (41.4%) | 12 (17.2%) | 4 (5.7%) |

| Post (N = 15) | 5 (33.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 3 (20%) |

| Strives to reach/her goals | ||||

| Pre (N = 70) | 28 (40%) | 27 (38.6%) | 9 (12.8%) | 6 (8.6%) |

| Post (N = 15) | 4 (26.7%) | 7 (46.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (20%) |

| Adapts easily to new situations | ||||

| Pre (N = 70) | 19 (27.1%) | 32 (45.7%) | 14 (20%) | 5 (7.2%) |

| Post (N = 15) | 4 (26.7%) | 7 (46.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (20%) |

| Enjoys being with other people | ||||

| Pre (N = 70) | 44 (62.9%) | 18 (25.7%) | 3 (4.3%) | 5 (7.1%) |

| Post (N = 15) | 10(66.7%) | 2(13.3%) | 0 | 3(20%) |

| Enjoys being with his/her friends | ||||

| Pre (N = 70) | 54 (77.2%) | 9 (12.9%) | 2 (2.8%) | 5 (7.1%) |

| Post (N = 15) | 12 (80%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (20%) |

| Seeks out activities that make him/her happy | ||||

| Pre (N = 70) | 50 (71.5%) | 13 (18.6%) | 2 (2.8%) | 5 (7.1%) |

| Post (N = 15) | 3 (20%) | 6 (40%) | 3 (20%) | 3 (20%) |

| Willing to share his/her positive emotions with others | ||||

| Pre (N = 70) | 39 (55.7%) | 19 (27.2%) | 7 (10%) | 5 (7.1%) |

| Post (N = 15) | 3 (20%) | 7 (46.7%) | 2 (13.3%) | 3 (20%) |

| Willing to share his/her negative emotions with others | ||||

| Pre (N = 70) | 17 (24.3%) | 36 (51.4%) | 12 (17.2%) | 5 (7.1%) |

| Post (N = 15) | 2 (13.3%) | 7 (46.7%) | 3 (20%) | 3 (20%) |

| Question | Strongly Agree | Partly Agree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Partly Disagree | Strongly Disagree | No Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have access to quality, research-based Australian resources to provide support to young children from Defence families | ||||||

| Pre % * (N = 29) | 1 (3.4%) | 5 (17.2%) | 6 (20.7%) | 8 (27.6%) | 9 (31%) | 0 |

| Post n (%) (N = 15) | 5 (33.3%) | 4 (26.7%) | 3 (20.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| I have received training or professional development regarding supporting children from Defence families | ||||||

| Pre % * (N = 29) | 1 (3.5%) | 5 (17.2%) | 1 (3.5%) | 6 (20.7%) | 16 (55.2%) | 0 |

| Post n (%) (N = 15) | 3 (20.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (20.0%) | 5 (33.3%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resources | N = 70 | % | N = 15 | % |

| Children’s storybooks (hard copy) | 37 | 52.9 | 13 | 86.7 |

| Children’s online programmes | 3 | 4.3 | 3 | 20.0 |

| Educational games | 12 | 17.1 | 5 | 33.3 |

| Activity books/project books | 22 | 31.4 | 4 | 26.7 |

| Other activities | 23 | 33 | 1 | 6.7 |

| Participant Comment | Explanation of the Issue | Implemented Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The format of the resources needs refining as it’s a bit clunky at the moment. The info is all there, but a regular website rather than this style of layout would be easier to follow. It’s a good resource, but it needs some refinement in development. I struggled to access it every time I tried to log in and then gave up half the time. An easily accessible app that keeps you logged in and sends weekly notifications to remind you of its resources would be a lot better for mums trying to juggle everything in the kids’ world and full-time work. The emails were so few and far between that I forgot it existed for a while. Better images, graphics and design are needed. I had a lot of trouble accessing and using the programme. I’m usually not too bad with technology, but I really struggled and gave up. So, I never got to use the program, which was a little disappointing. | The resources were on a password protected learning platform that some users had trouble accessing. There was no index system to easily locate specific resources. The headings for each online module tile needed refinement to support the user. | The resources were made available without the need for an account (as was initially planned after the resources were tested). An index tile was added to each suite of resources for children, parents, educators, and support workers. The headings were refined to support usability. |

| It’s a great concept, just needs some work on usability. Ideally, it could be bundled with a family app, as I found the resources helpful for myself as a defence spouse, as well as the kids. If there was a way to create a user profile to address each member of the family, DVA [Department of Veterans’ Affairs] and mental health info, etc, for the serving member, community resources, mental health tips, etc, for the spouse and the age-appropriate guides for each of the kids. I found there were a lot of resources… perhaps too many… it looked like I’d have to do a lot of work to use these resources efficiently. I found clicking on the links a bit clunky and would have preferred just to flick though digitally or read a webpage rather than save links to my computer to access them. Tried to view the resources in January 2022—not uploaded yet. Started the school year and got busy so didn’t get a chance to log back in. Need to have resources available in school holidays before we get swamped with work. Asked my business manager to buy the paper books, don’t think the order went through as you’re not DET [Department of Education and Training] approved supplier. Please make them available to public primary schools in NSW or send them out free of charge to every primary school that has a DSM. Thanks! | The users had to navigate many topics and pages to find specific resources for the children they were supporting. Since they are busy in their roles, and the children’s needs were dynamic, this was a time-consuming process. | A free, anonymous, digital personalised programme was co-created to support usability (see http://program.ecdefenceprograms.com/) (accessed on 10 September 2025). This involves the end-user filling out three questions using a series of boxes to tick:

|

| I think the resources from this new project are better suited to teachers and support workers than parents. Although some of the resources would be more useful to younger children. My son is 8 and the stories were a bit too young for him and very similar to stories we have read before. … It wasn’t clear what to do with some of the workbooks, but they looked similar to what some child psychologists use for helping kids with their feelings. I guess the kids are meant to draw on the pages, but it didn’t say that when I accessed it. This sort of resource is harder for parents to use, but very useful in a clinical setting. I think these resources are fantastic, just perhaps not for parents—more for clinicians/teachers. | Some of the resources did not provide detailed instructions on how to use them with children. Most of the initial activities and resources were designed for children aged 2–8 years, with the majority targeting children aged 2–6 years. | We provided more detailed instructions for parents on how to engage their children in the personalised storybooks and project books to make them more user-friendly. We have created additional activities and resources for parents, educators, and support workers to engage children up to 12 years old, and co-created further research-based storybooks for children up to 10 years old. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rogers, M.; Sims, M.; Siebler, P.; Gossner, M.; Thorsteinsson, E.B. Co-Created Psychosocial Resources to Support the Wellbeing of Children from Military Families: Usability Study. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111441

Rogers M, Sims M, Siebler P, Gossner M, Thorsteinsson EB. Co-Created Psychosocial Resources to Support the Wellbeing of Children from Military Families: Usability Study. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111441

Chicago/Turabian StyleRogers, Marg, Margaret Sims, Philip Siebler, Michelle Gossner, and Einar B. Thorsteinsson. 2025. "Co-Created Psychosocial Resources to Support the Wellbeing of Children from Military Families: Usability Study" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111441

APA StyleRogers, M., Sims, M., Siebler, P., Gossner, M., & Thorsteinsson, E. B. (2025). Co-Created Psychosocial Resources to Support the Wellbeing of Children from Military Families: Usability Study. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111441