Linking Self-Regulation Scaffolding to Early Math Achievement: Evidence from Chilean Preschools

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Math in the Chilean Context

1.2. The Current Study

- Instructional self-regulation scaffolding behaviors would be positively associated with children’s mathematics scores.

- Organizational self-regulation scaffolding behaviors would be positively associated with children’s mathematics scores.

- Emotional self-regulation scaffolding behaviors would be positively associated with children’s mathematics scores.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Procedure

Preschool Teachers’ Video Recordings

2.4. Instruments

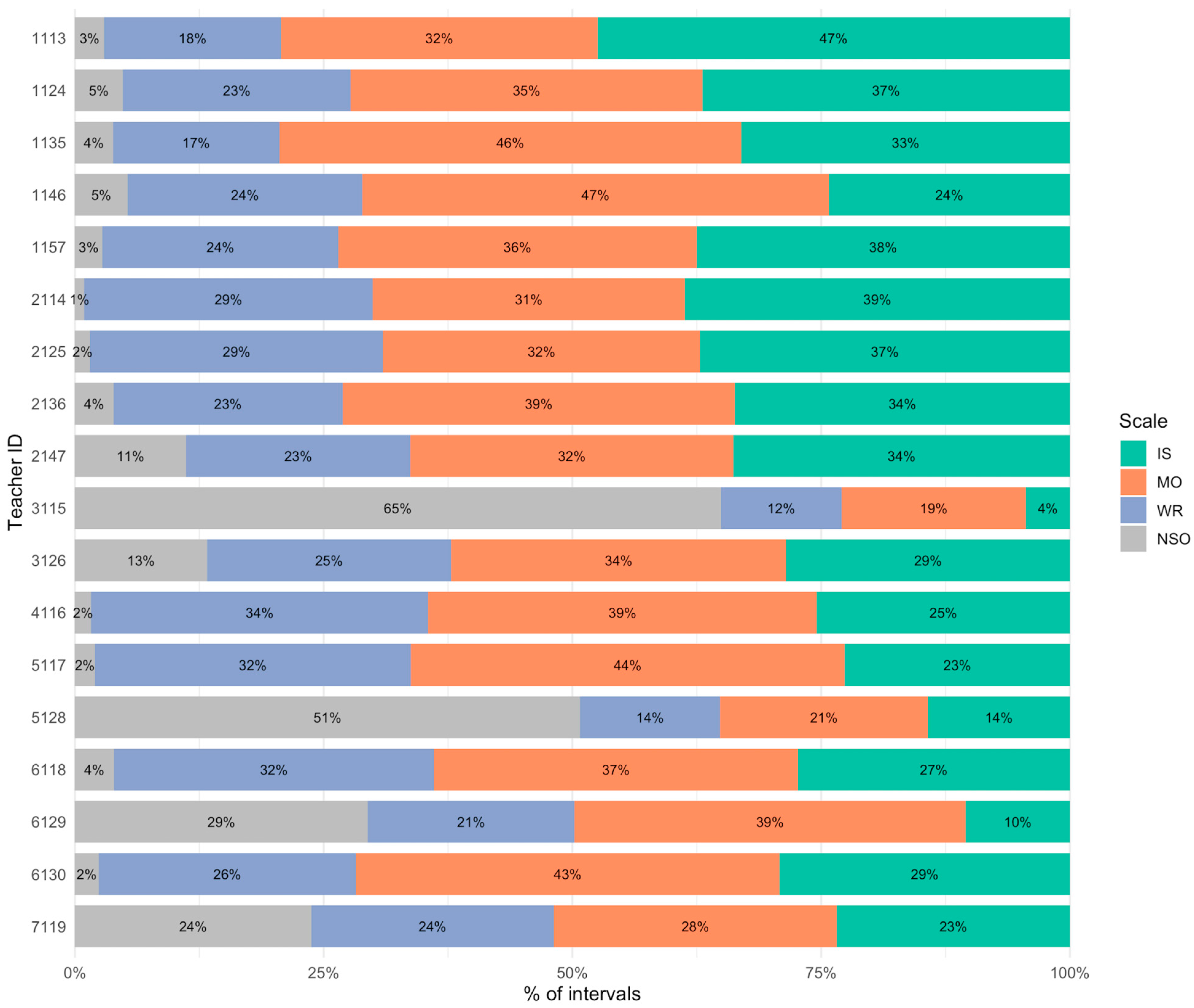

2.4.1. Coding System

- (i)

- Instructional Strategy (IS): It indicates whether preschool teachers employ self-regulation scaffolding behaviors to guide children in participating and engaging with the learning processes in the classroom.

- (ii)

- Management Organization (MO): It reflects behaviors that foster self-regulation as teachers manage and structure their classroom environment. The codes illustrate how preschool teachers handle classroom organization to enhance the learning process, thereby promoting self-regulation skills.

- (iii)

- Warmth Responsivity (WR): It reflects the scaffolding behaviors that preschool teachers use to motivate children to achieve and complete tasks.

2.4.2. Children’s Math Achievement

2.4.3. Control Variables

2.4.4. Analytic Plan

2.4.5. Missing Data

2.5. Results

2.5.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.5.2. Hierarchical Linear Model Analysis

2.5.3. Association Between Preschool Teachers’ Behaviors and Children’s Math Achievement

3. Discussion

3.1. Instructional Strategy Behaviors and Children’s Math Achievement

3.2. Management Organization Behaviors and Children’s Math Achievement

3.3. Warmth Responsivity Behaviors and Children’s Math Achievement

3.4. Limitations and Future Directions

3.5. Policy and Practice Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arievitch, I. M., & Haenen, J. P. P. (2005). Connecting sociocultural theory and educational practice: Galperin’s approach. Educational Psychologist, 40(3), 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardack, S., & Obradović, J. (2019). Observing teachers’ displays and scaffolding of executive functioning in the classroom context. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 62, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, L. C., Del Río, M. F., & Susperreguy, M. I. (2018). What do preschool teachers do to teach mathematics? A study in chilean classrooms. Bordon, Revista de Pedagogia, 70(3), 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C., & Raver, C. C. (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: A developmental psychobiological approach. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 711–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C., & Razza, R. P. (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child development, 78(2), 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadima, J., Verschueren, K., Leal, T., & Guedes, C. (2016). Classroom interactions, dyadic teacher–child relationships, and self–regulation in socially disadvantaged young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, C. E., Kim, H., Duncan, R. J., Becker, D. R., & McClelland, M. M. (2019). Bidirectional and co-developing associations of cognitive, mathematics, and literacy skills during kindergarten. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 62, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, C. E., & Morrison, F. J. (2011). Teacher activity orienting predicts preschoolers’ academic and self-regulatory skills. Early Education & Development, 22(4), 620–648. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, R. C., Mokrova, I. L., Vernon-Feagans, L., & Burchinal, M. R. (2019). Cumulative classroom quality during pre-kindergarten and kindergarten and children’s language, literacy, and mathematics skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, C., & Farran, D. (2020). Academic gains in kindergarten related to eight classroom practices. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Interreliability standards in psychological evaluations. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C. A., Pritchard, V. E., & Woodward, L. J. (2010). Preschool executive functioning abilities predict early mathematics achievement. Developmental Psychology, 46(5), 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clements, D. H., Sarama, J., & Germeroth, C. (2016). Learning executive function and early mathematics: Directions of causal relations. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 36, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, C. M. D., Adams, A., Zargar, E., Wood, T. S., Hernandez, B. E., & Vandell, D. L. (2020). Observing individual children in early childhood classrooms using Optimizing Learning Opportunities for Students (OLOS): A feasibility study. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 52, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, C. M. D., Spencer, M., Day, S. L., Giuliani, S., Ingebrand, S. W., McLean, L., & Morrison, F. J. (2014). Capturing the complexity: Content, type, and amount of instruction and quality of the classroom learning environment synergistically predict third graders’ vocabulary and reading comprehension outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(3), 762–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPEIP (Centro de Perfeccionamiento, Experimentación e Investigaciones Pedagógicas). (2021). Estándares orientadores para carreras de pedagogía en educación parvularia. Ministerio de Educación de Chile. Available online: https://estandaresdocentes.mineduc.cl (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- DeFlorio, L., Klein, A., Starkey, P., Swank, P. R., Taylor, H. B., Halliday, S. E., Beliakoff, A., & Mulcahy, C. (2019). A study of the developing relations between self-regulation and mathematical knowledge in the context of an early math intervention. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 46, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degol, J. L., & Bachman, H. J. (2015). Preschool teachers’ classroom behavioral socialization practices and low-income children’s self-regulation skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 31, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, G. J., Dowsett, C. J., Claessens, A., Magnuson, K., Huston, A. C., Klebanov, P., Pagani, L. S., Feinstein, L., Engel, M., Brooks-Gunn, J., Sexton, H., Duckworth, K., & Japel, C. (2007). School readiness and later achievement. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1428–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, P. W., & Waajid, B. (2012). Emotion knowledge and self-regulation as predictors of preschoolers’ cognitive ability, classroom behavior, and social competence. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 30(4), 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development, 76(5), 949–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofer, K. G., Farran, D. C., & Cummings, T. P. (2013). Preschool children’s math-related behaviors mediate curriculum effects on math achievement gains. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(3), 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva, D., Weiland, C., Barata, M. C., Yoshikawa, H., Snow, C., Treviño, E., & Rolla, A. (2015). Teacher–child interactions in Chile and their associations with prekindergarten outcomes. Child Development, 86(3), 781–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A., Wright, A., Phillips, D. A., Castle, S., & Johnson, A. D. (2024). Exploring the features of the self-regulatory environment in kindergarten classrooms. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 93, 101659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A. S., & Cicchetti, D. (2010). Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22(3), 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, M. M., & Cameron, C. E. (2011). Self-regulation and academic achievement in elementary school children. In Thriving in childhood and adolescence: The role of self-regulation processes. New directions for child and adolescent development (Vol. 133, pp. 24–44). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, M. M., & Cameron, C. E. (2012). Self-regulation early childhood: Improving conceptual clarity and developing ecologically valid measures. Child Development Perspectives, 6(2), 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, M. M., Cameron, C. E., & Dhallghen, J. (2019). The development of self-regulation in young children. In D. Whitebread, V. Grau, K. Kumpulainen, M. McClelland, N. Perry, & D. Pino-Parternak (Eds.), Handbook of developmental psychology and early childhood education (1st ed.). SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon, R. D., & Blair, C. (2019). Bidirectional relations among executive function, teacher–child relationships, and early reading and math achievement: A cross-lagged panel analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 46, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, L., Sparapani, N., Toste, J. R., & Connor, C. M. (2016). Classroom quality as a predictor of first graders’ time in non-instructional activities and literacy achievement. Journal of School Psychology, 56, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, M. F., Susperreguy, M. I., & Morrison, F. J. (2023). Self-regulation scaffolding behaviors of teachers in Chilean preschool classrooms. Early Education and Development, 34(6), 1305–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, F. J., Ponitz, C. C., & McClelland, M. M. (2010). Self-regulation and academic achievement in the transition to school. In S. D. Calkins, & M. A. Bell (Eds.), Child development at the intersection of emotion and cognition (pp. 203–224). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munakata, Y., Snyder, H. R., & Chatham, C. H. (2012). Developing cognitive control: Three key transitions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(2), 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Sandoval, A. F., Woodcock, R. W., McGrew, K. S., Mather, N., & Ardoino, G. (2005). Batería III Wood-cock-Muñoz. Ciencias Psicológicas, 3(2), 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D. A., Hutchison, J., Martin, A., Castle, S., & Johnson, A. D. (2022). First do no harm: How teachers support or undermine children’s self-regulation. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 59, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce Pradenas, L. E., & Strasser Salinas, K. (2019). Diversidad de oportunidades de aprendizaje matemático en aulas chilenas de kínder de distinto nivel socioeconómico. Pensamiento Educativo, 56(2), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prykanowski, D. A., Martinez, J. R., Reichow, B., Conroy, M. A., & Huang, K. (2018). Brief report: Measurement of young children’s engagement and problem behavior in early childhood settings. Behavioral Disorders, 44(1), 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purpura, D. J., Schmitt, S. A., & Ganley, C. M. (2017). Foundations of mathematics and literacy: The role of executive functioning components. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 153, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., La Paro, K. M., Downer, J. T., & Pianta, R. C. (2005). The contribution of classroom setting and quality of instruction to children’s behavior in kindergarten classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 105(4), 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, S. A., Duncan, R. J., Budrevich, A., & Korucu, I. (2020). Benefits of behavioral self-regulation in the context of high classroom quality for preschoolers’ mathematics. Early Education and Development, 31(3), 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibbe, L. E., Montroy, J. J., Bowles, R. P., & Morrison, F. J. (2019). Self-regulation and the development of literacy and language achievement from preschool through second grade. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 46, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, K., Darricades, M., Mendive, S., & Barra, G. (2018). Instructional activities and the quality of language in Chilean preschool classrooms. Early Education and Development, 29(3), 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susperreguy, M. I., Di Lonardo Burr, S., Xu, C., Douglas, H., & LeFevre, J. A. (2020). Children’s home numeracy environment predicts growth of their early mathematical skills in kindergarten. Child Development, 91(5), 1663–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Braak, D., Lenes, R., Purpura, D. J., Schmitt, S. A., & Størksen, I. (2022). Why do early mathematics skills predict later mathematics and reading achievement? The role of executive function. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 214, 105306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). Mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(3), 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, L., Spilt, J., Verschueren, K., Piccinin, C., & Baeyens, D. (2018). The classroom as a developmental context for cognitive development: A meta-analysis on the importance of teacher–student interactions for children’s executive functions. Review of Educational Research, 88(1), 125–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, V. E., & Williford, A. P. (2020). Context influences on task orientation among preschoolers who display disruptive behavior problems. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 51, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1997). The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky (R. Rieber, Ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, T. W., Duncan, G. J., Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2018). What is the long-run impact of learning mathematics during preschool? Child Development, 89(2), 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P. D. (2015). Executive function: Reflection, iterative reprocessing, complexity, and the developing brain. Developmental Review, 38, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instructional Strategy (IS) | Examples |

| Models an example (provides external cues to explain to children what they should do) | “With my finger up and down… I can draw number 1,” while drawing the number 1. |

| Promotes establishing connections (supports children in linking different concepts) | “Heavy and light are two qualities of the objects. Heavy as me because I’m bigger and tall than you. Anyone can answer you are light or heavy than me?” |

| Engages in in-depth analysis of the material (engages children in analyzing a section of the material) | “Now we are going to observe the number line that we have here. We are going to look at the spaces of distance between numbers… Look at the difference between 14 and 18… let’s count them”. |

| Management Organization (MO) | Examples |

| Reminds children about behavior expectations (reinforces rules of good conduct when children demonstrate expected behavior or when they misbehave) | “We need silence to listen us. Please let’s hear what xx have to say…she was saying that sorting is…” |

| Gives step-by-step instructions (provides step-by-step instructions for an activity or behavior) | “Now we are going to read the challenge and then we are going to write the first part of it” |

| References schedule for the day (explain the daily schedule) | “After eat lunch we are going to learn counting strategies using blocks. Please don’t forget that for this time we are going to read a book before it” |

| Repeats instructions (repeats an instruction verbally more than two times in a interval of 30s each) | “We need to separate those (group of balls) in three equal parts” then the teacher goes to another group and repeats “remember that this group have to be divided in three parts, and they have to be equal” |

| Provides students support (supports children as they transition between activities or settings) | “Teacher help children to pick up the materials from math corner at the classroom” |

| Secures attention (employs verbal and/or physical support to capture children’s attention) | Teacher uses a puppet called “Perico” to secures attention and being able to read a math problem on the blackboard. |

| Warmth Responsivity (WR) | Examples |

| Offers recommendations for improvement (advises children on their work during activities) | When the child answers 29 instead of 19, the teacher writes on the blackboard “29 is this number you wrote… you see it have a 2…you see, but 19 has a 1. That way you can write the 19 and name it correctly” |

| Provides positive reinforcement (offers praise or tangible reinforcement when children successfully complete an activity or display positive behavior or attitude) | Gives a star for good answer when children put the correct number in a sequence. |

| Encourages perseverance (Gives verbal encouragement to help children persevere with challenging activities) | Children are comparing two bags of different wight. Teacher says: “Let’s go again and see what happen when you compare this bag with this other. Can you tell me what bag is heavier? See, I knew it that you were capable to solve that”. |

| Level 1 (Student) Correlations | |||||

| Variable | Math achievement (T2) | Math achievement (T1) | Age | Family income (1 = high) | Gender (1 = boy) |

| Math achievement (T2) | — | ||||

| Math achievement (T1) | 0.59 *** | — | |||

| Age | 0.25 *** | 0.27 *** | — | ||

| Family income (1 = high) | 0.29 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.11 * | — | |

| Gender (1 = boy) | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.12 * | — |

| Level 2 (Teacher) Correlations | |||||

| Variable | Instructional Strategies | Management Organization | Warmth Responsivity | ||

| Instructional Strategies | — | ||||

| Management Organization | 0.37 *** | — | |||

| Warmth Responsivity | 0.28 *** | 0.54 *** | — | ||

| Effect | Null Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Coef. (SE) | Coef. (SE) | Coef. (SE) | 95% CI | Std β |

| Fixed effects | |||||

| Level 1 (students) | |||||

| Intercept | 15.06 *** (0.44) | 14.80 *** (0.40) | 14.79 *** (0.36) | [14.07, 15.50] | — |

| Math Achievement (T1) | — | 0.58 *** (0.05) | 0.58 *** (0.05) | [0.49, 0.67] | 0.53 |

| Children age | — | 0.07 * (0.04) | 0.08 * (0.04) | [0.01, 0.15] | 0.08 |

| Family income (binary) | — | 0.42 (0.38) | 0.52 (0.38) | [−0.24, 1.27] | 0.07 |

| Gender (binary) | — | 0.16 (0.29) | 0.17 (0.29) | [−0.41, 0.74] | 0.02 |

| Level 2 (teachers) | |||||

| Instructional Strategies | — | — | −0.09 (0.60) | [−1.28, 1.09] | −0.01 |

| Management Organization | — | — | 1.62 * (0.77) | [0.12, 3.13] | 0.20 |

| Warmth Responsivity | — | — | −1.51 * (0.59) | [−2.66, −0.35] | −0.22 |

| Random effects (variance components) | |||||

| Teacher-level variance | 2.87 | 1.40–1.75 | 0.89–1.36 | ||

| Residual variance | 11.79 | 7.65–8.11 | 7.66–8.13 | ||

| Total variance | 14.66 | 9.11–9.70 | 8.66–9.37 | ||

| ICC (Teacher %) | 20% | 15–18% | 10–15% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Montoya, M.F.; Tornero, B.; Palacios Farias, D.; Morrison, F.J. Linking Self-Regulation Scaffolding to Early Math Achievement: Evidence from Chilean Preschools. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1426. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111426

Montoya MF, Tornero B, Palacios Farias D, Morrison FJ. Linking Self-Regulation Scaffolding to Early Math Achievement: Evidence from Chilean Preschools. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1426. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111426

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontoya, Maria F., Bernardita Tornero, Diego Palacios Farias, and Frederick J. Morrison. 2025. "Linking Self-Regulation Scaffolding to Early Math Achievement: Evidence from Chilean Preschools" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1426. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111426

APA StyleMontoya, M. F., Tornero, B., Palacios Farias, D., & Morrison, F. J. (2025). Linking Self-Regulation Scaffolding to Early Math Achievement: Evidence from Chilean Preschools. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1426. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111426