The Impact of an Immersive Block Model on International Postgraduate Student Success and Satisfaction: An Australian Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

PG students are a valuable sector within HE and are often neglected in terms of both the research being performed and the differentiation of their expectations in comparison to UG students. In particular, international PG students bring diversity and other benefits to the classroom so they should be listened to (p. 94).

- How do success rates in a traditional model compare with success rates in an immersive block model?

- How does unit satisfaction in a traditional model compare with unit satisfaction in an immersive block model?

- How do students experience immersive block model learning?

1.1. International Student Success in HE

1.2. Immersive Block Models in HE

2. The Southern Cross Model: A Case Study

- Self-access online modules that are media-rich, interactive and responsive.

- Scheduled classes that are guided and interactive, involving activities such as discussion, problem-based scenarios, and simulations.

- Assessments that are authentic and scaffolded, with no more than three assessments per unit (see Roche et al., 2024 for a more detailed description of the pedagogy of the SCM, Goode et al., 2022 for an example of its application, and Wilson et al., 2025a for an outline of how assessment was reformed for block delivery).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Quantitative Data Collection and Preparation

- T0: Baseline traditional semester delivery, prior to the introduction of the SCM (2019);

- T1: Traditional semester delivery during the SCM’s progressive implementation (2021–2022);

- SCM: Units delivered in the six-week SCM (2021–2024).

- Home region: Africa and Middle East; North-East Asia (e.g., China, Japan, Korea); South America; Southeast Asia (e.g., Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia); and Southern and Central Asia (e.g., India, Sri Lanka, Nepal)

- Disciplines: Information Technology; Engineering and Related Technologies; and Management and Commerce

- Age range: 20–24 years; 25–34 years; and 35+ years

- Gender: Female; Male.

3.2. Quantitative Data Analysis

3.3. Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

- Participants’ motivations for choosing the host institution;

- Initial expectations and perceptions of the SCM;

- Perceptions of how well they were able to balance study, work and life in the SCM;

- Perceptions and experiences of the focused, guided and active pedagogy of the SCM;

- How prepared they felt for their future career or future study.

4. Results

4.1. Student Success

4.2. Unit Satisfaction

4.3. Qualitative

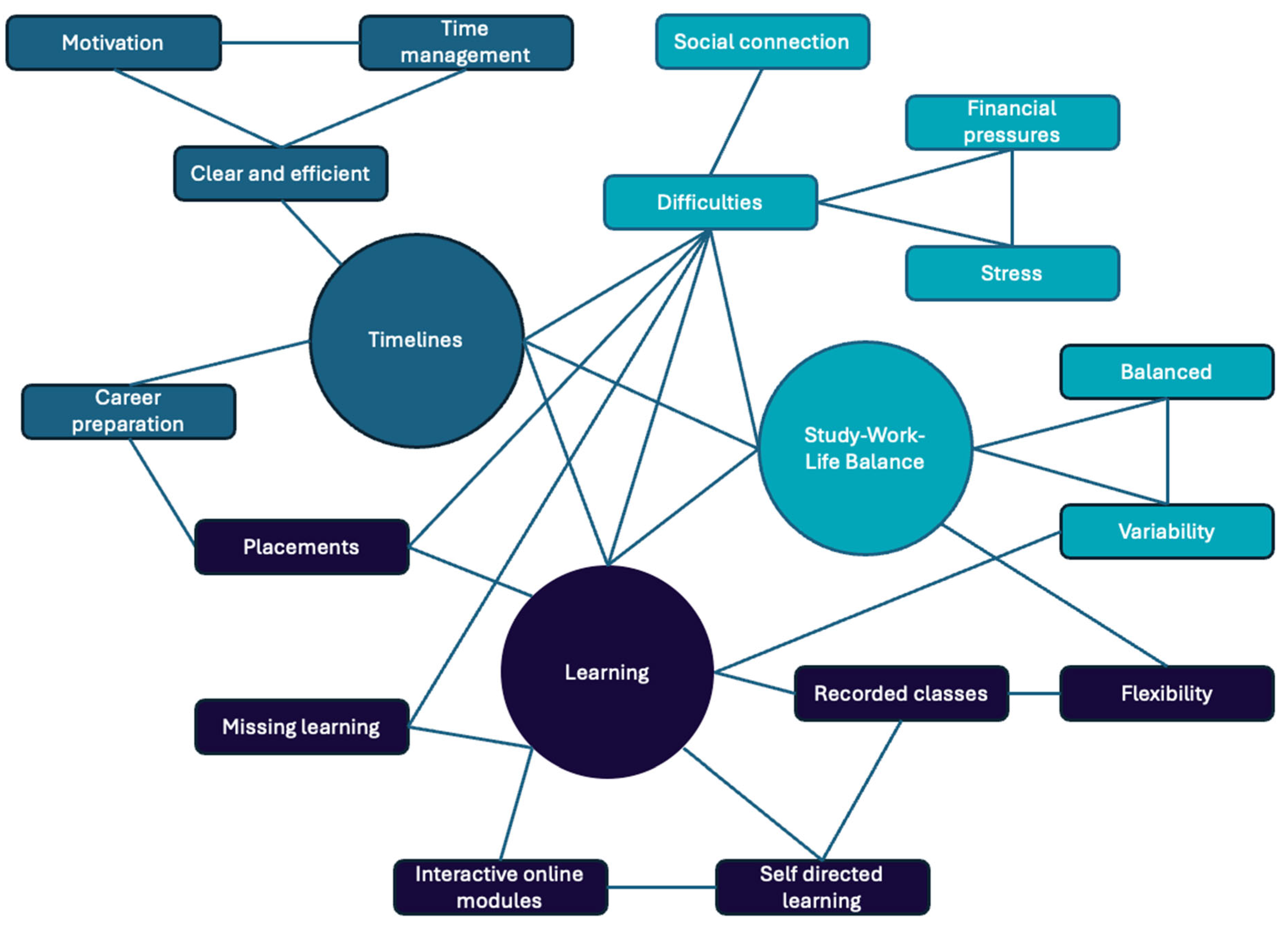

4.3.1. Timelines

4.3.2. Learning

4.3.3. Study-Work–Life Balance

[The shorter model is] helpful in some units. And then, as I’ve said before, it is not very helpful in others, especially if it is more like technical units where it is skill-based and you really need the time and focus to actually understand the content.

5. Discussion

Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Success (S) Models | Unit Satisfaction (US) Models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Predictors | QIC | Model | Predictors | QIC |

| MS0 | Null | 17,571.2 | MUS0 | Null | 4434.4 |

| MS1 | Delivery model | 16,167.5 | MUS1 | Delivery model | 4361.3 |

| MS2 | As above, plus: Home region | 15,969.9 | MUS2 | As above, plus: Discipline | 4347.4 |

| MS3 | As above, plus: Gender | 15,682.7 | MUS3 | As above, plus: Age | 4349.0 |

| MS4 | As above, plus: Age | 15,618.1 | MUS4 | As above, plus: Home region | 4350.1 |

| MS5 | As above, plus: Discipline | 15,585.0 | MUS5 | As above, plus: Gender | 4358.1 |

| MS6 | As above, plus: Delivery model * Home region | 15,565.5 | MUS6 | As above, plus: Delivery model * Age | 4354.1 |

| MS7 | As above, plus: Delivery model * Gender | 15,464.2 | MUS7 | As above, plus: Delivery model * Home region | 4363.4 |

| MS8 | As above, plus: Delivery model * Age | 15,429.4 | MUS8 | As above, plus: Delivery model * Gender | 4364.0 |

| MS9 | As above, plus: Delivery model * Discipline | 15,369.8 | MUS9 | As above, plus delivery model * Discipline | 4375.2 |

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference: T0 | |||||

| SCM | 2.31 | 1.11 | 4.82 | 0.025 | |

| T1 | 0.95 | 0.47 | 1.93 | 0.881 | |

| Southern and Central Asia | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.70 | <0.001 | |

| Southeast Asia | 1.36 | 0.79 | 2.36 | 0.268 | |

| South America | 0.91 | 0.28 | 2.92 | 0.875 | |

| Africa and Middle East | 1.83 | 0.84 | 3.97 | 0.129 | |

| 35+ | 2.48 | 1.51 | 4.09 | <0.001 | |

| 25–34 | 1.48 | 1.29 | 1.69 | <0.001 | |

| Male | 0.36 | 0.31 | 0.42 | <0.001 | |

| Engineering | 1.21 | 0.99 | 1.47 | 0.062 | |

| Information Technology | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.89 | 0.002 | |

| SCM*Southern and Central Asia | 1.14 | 0.52 | 2.46 | 0.746 | |

| SCM*Southeast Asia | 0.67 | 0.23 | 1.96 | 0.468 | |

| SCM*South America | 3.30 | 0.59 | 18.56 | 0.175 | |

| SCM*Africa and Middle East | 0.40 | 0.11 | 1.52 | 0.180 | |

| SCM*Male | 2.15 | 1.49 | 3.10 | <0.001 | |

| SCM*35+ | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.47 | <0.001 | |

| SCM*25–34 | 0.76 | 0.55 | 1.04 | 0.083 | |

| SCM*Engineering | 1.53 | 0.94 | 2.50 | 0.088 | |

| SCM*Information Technology | 2.59 | 1.62 | 4.16 | <0.001 | |

| T1*Southern and Central Asia | 1.31 | 0.67 | 2.56 | 0.427 | |

| T1*Southeast Asia | 0.69 | 0.27 | 1.76 | 0.433 | |

| T1*South America | 1.92 | 0.45 | 8.24 | 0.379 | |

| T1*Africa and Middle East | 1.12 | 0.37 | 3.43 | 0.842 | |

| T1*Male | 2.22 | 1.58 | 3.13 | <0.001 | |

| T1*35+ | 0.47 | 0.20 | 1.08 | 0.074 | |

| T1*25–34 | 0.68 | 0.44 | 1.03 | 0.067 | |

| T1*Engineering | 1.00 | 0.63 | 1.59 | 0.994 | |

| T1*Information Technology | 2.52 | 1.64 | 3.88 | <0.001 | |

| Reference: T1 | |||||

| SCM | 2.44 | 1.07 | 5.55 | 0.033 | |

| T0 | 1.06 | 0.52 | 2.15 | 0.881 | |

| Southern and Central Asia | 0.64 | 0.36 | 1.16 | 0.140 | |

| Southeast Asia | 0.93 | 0.40 | 2.18 | 0.874 | |

| South America | 1.75 | 0.67 | 4.57 | 0.253 | |

| Africa and Middle East | 2.05 | 0.73 | 5.71 | 0.172 | |

| 35+ | 1.16 | 0.58 | 2.33 | 0.671 | |

| 25–34 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 1.49 | 0.989 | |

| Male | 0.80 | 0.58 | 1.10 | 0.172 | |

| Engineering | 1.21 | 0.78 | 1.87 | 0.401 | |

| Information Technology | 1.83 | 1.24 | 2.68 | 0.002 | |

| SCM*Southern and Central Asia | 0.87 | 0.35 | 2.12 | 0.753 | |

| SCM*Southeast Asia | 0.98 | 0.32 | 2.98 | 0.973 | |

| SCM*South America | 1.72 | 0.40 | 7.29 | 0.463 | |

| SCM*Africa and Middle East | 0.36 | 0.08 | 1.63 | 0.185 | |

| SCM*Male | 0.97 | 0.63 | 1.48 | 0.877 | |

| SCM*35+ | 0.49 | 0.20 | 1.21 | 0.122 | |

| SCM*25–34 | 1.12 | 0.69 | 1.80 | 0.646 | |

| SCM*Engineering | 1.53 | 0.83 | 2.85 | 0.175 | |

| SCM*Information Technology | 1.03 | 0.61 | 1.72 | 0.918 | |

| T0*Southern and Central Asia | 0.76 | 0.39 | 1.49 | 0.427 | |

| T0*Southeast Asia | 1.46 | 0.57 | 3.76 | 0.433 | |

| T0*South America | 0.52 | 0.12 | 2.23 | 0.379 | |

| T0*Africa and Middle East | 0.89 | 0.29 | 2.73 | 0.842 | |

| T0*Male | 0.45 | 0.32 | 0.63 | <0.001 | |

| T0*35+ | 2.14 | 0.93 | 4.92 | 0.074 | |

| T0*25–34 | 1.48 | 0.97 | 2.25 | 0.067 | |

| T0*Engineering | 1.00 | 0.63 | 1.59 | 0.994 | |

| T0*Information Technology | 0.40 | 0.26 | 0.61 | <0.001 | |

| Model QIC = 15369.8 | |||||

| Observations = 14,340 | |||||

| Subjects = 3122 | |||||

| Measurements per subject = 1–24 | |||||

| Working correlation matrix (exchangeable) = 0.295 | |||||

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference: T0 | |||||

| SCM | 1.89 | 1.24 | 2.88 | 0.003 | |

| T1 | 2.99 | 1.44 | 6.20 | 0.003 | |

| Southern and Central Asia | 0.71 | 0.47 | 1.07 | 0.098 | |

| Southeast Asia | 0.72 | 0.42 | 1.22 | 0.218 | |

| Africa, Middle East, and South America | 0.63 | 0.37 | 1.07 | 0.085 | |

| 35+ | 1.74 | 0.83 | 3.65 | 0.143 | |

| 25–34 | 1.10 | 0.85 | 1.43 | 0.472 | |

| Male | 0.93 | 0.75 | 1.14 | 0.486 | |

| Engineering | 1.65 | 1.21 | 2.25 | 0.002 | |

| Information Technology | 0.96 | 0.73 | 1.26 | 0.774 | |

| SCM*35+ | 0.42 | 0.16 | 1.08 | 0.072 | |

| SCM*25–34 | 1.24 | 0.76 | 2.01 | 0.384 | |

| T1*35+ | 0.30 | 0.08 | 1.16 | 0.081 | |

| T1*25–34 | 0.61 | 0.27 | 1.37 | 0.231 | |

| Reference: T1 | |||||

| SCM | 0.63 | 0.30 | 1.34 | 0.234 | |

| T0 | 0.33 | 0.16 | 0.69 | 0.003 | |

| Southern and Central Asia | 0.71 | 0.47 | 1.07 | 0.098 | |

| Southeast Asia | 0.72 | 0.42 | 1.22 | 0.218 | |

| Africa, Middle East, and South America | 0.63 | 0.37 | 1.07 | 0.085 | |

| 35+ | 0.52 | 0.16 | 1.68 | 0.273 | |

| 25–34 | 0.67 | 0.31 | 1.45 | 0.312 | |

| Male | 0.93 | 0.75 | 1.14 | 0.486 | |

| Engineering | 1.65 | 1.21 | 2.25 | 0.002 | |

| Information Technology | 0.96 | 0.73 | 1.26 | 0.774 | |

| SCM*35+ | 1.40 | 0.40 | 4.93 | 0.599 | |

| SCM*25–34 | 2.03 | 0.88 | 4.71 | 0.097 | |

| T0*35+ | 3.37 | 0.86 | 13.13 | 0.081 | |

| T0*25–34 | 1.64 | 0.73 | 3.68 | 0.231 | |

| Model QIC = 4354.1 | |||||

| Observations = 4903 | |||||

| Subjects = 1328 | |||||

| Measurements per subject = 1–14 | |||||

| Working correlation matrix (exchangeable) = 0.179 | |||||

References

- Abdul Aziz, F. F., Gheda, L. M., Hamid, S. A., & Mohamad Nusran, N. F. (2025). Exploring the impacts of work-related stress on master’s project and completion rates among post graduate working learners. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 8(7), 4051–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. T., & Roche, T. (2021). Making the connection: Examining the relationship between undergraduate students’ digital literacy and academic success in an English medium instruction (EMI) university. Education and Information Technologies, 26(4), 4601–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanzalon, J. J. (2024). Assessment of postgraduate programs for international students in selected Australian universities: Input for policy making for international postgraduate students. International Journal on Integrating Technology in Education, 13(4), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzukari, R., & Wei, T. (2024). Article gender differences in the acculturative stress of international students: A meta-analysis. Journal of International Students, 14(5), 141–158. Available online: https://www.ojed.org/jis/article/view/6922 (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Ammigan, R., & Jones, E. (2018). Improving the student experience: Learning from a comparative study of international student satisfaction. Journal of Studies in International Education, 22(4), 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M. S. (2006). International students in English-speaking universities: Adjustment factors. Journal of Research in International Education, 5(2), 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkoudis, S., Dollinger, M., Baik, C., & Patience, A. (2019). International students’ experience in Australian higher education: Can we do better? Higher Education, 77(5), 799–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, A. M., & Gustafson, L. (2006). Impact of course length on student learning. Journal of Economics and Finance Education, 5(1), 26–37. Available online: http://www.economics-finance.org/jefe/econ/Gustafsonpaper.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Austin, P. C., Kapral, M. K., Vyas, M. V., Fang, J., & Yu, A. Y. X. (2024). Using multilevel models and generalized estimating equation models to account for clustering in neurology clinical research. Neurology, 103(9), e209947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2001). Broad and narrow fields: Australian Standard Classification of Education (ASCED). Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/classifications/australian-standard-classification-education-asced/2001/field-education-structure-and-definitions/structure/broad-and-narrow-fields (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). Standard Australian Classification of Countries (SACC). Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/classifications/standard-australian-classification-countries-sacc/latest-release#overview (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Bai, L., & Wang, Y. X. (2022). Combating language and academic culture shocks—International students’ agency in mobilizing their cultural capital. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 17(2), 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M. (2008). Convenience sampling. In P. J. Lavrakas (Ed.), Encyclopedia of survey research methods (Vol. 1, p. 149). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodine Al-Sharif, M. A., Koo, K., & Bista, K. (2025). International graduate students: Unique stories and missing voices in higher education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2025(181), 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, E., & Tyrrell, K. (2022). Block and blend: A mixed method investigation into the impact of a pilot block teaching and blended learning approach upon student outcomes and experience. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46(8), 1078–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E. J., Crane, L., Kinash, S., Bannatyne, A., Crawford, J., Hamlin, G., Judd, M.-M., Kelder, J.-A., Partridge, H., & Richardson, S. (2021). Australian postgraduate student experiences and anticipated employability: A national study from the students’ perspective. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 12(2), 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dawadi, S. (2020). Thematic analysis approach: A step by step guide for ELT research practitioners. Journal of NELTA, 25(1–2), 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaene, S. (2020). How we learn: The new science of education and the brain. Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, J. L., & Ammigan, R. (2021). What drives student recommendations? An empirical investigation of the learning experiences of international students in Australia, the UK, and the US. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education, 10(2), 1–27. Available online: https://ojed.org/jise/article/view/4086 (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Department of Education. (2024). 2023 section 7—Overseas students. Australian Government. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/resources/2023-section-7-overseas-students (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Department of Education. (2025). Key findings from the 2023 higher education student statistics. Australian Government. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/student-data/selected-higher-education-statistics-2023-student-data/key-findings-2023-student-data (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Collier. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, L., & O’Gorman, V. (2020). ‘Block teaching’– exploring lecturers’ perceptions of intensive modes of delivery in the context of undergraduate education. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(5), 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eames, M., Luttman, S., & Parker, S. (2018). Accelerated vs. traditional accounting education and CPA exam performance. Journal of Accounting Education 44, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C., Nguyen, T., Richardson, M., & Scott, I. (2018). Managing the transition from undergraduate to taught postgraduate study: Perceptions of international students studying in the UK. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 23(2), 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faught, B. E., Law, M., & Zahradnik, M. (2016). How much do students remember over time? Longitudinal knowledge retention in traditional versus accelerated learning environments. Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. Available online: https://heqco.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/How-Much-Do-Students-Remember-Over-Time.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(23), 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, E., Nieuwoudt, J. E., & Roche, T. (2022). Does online engagement matter? The impact of interactive learning modules and synchronous class attendance on student achievement in an immersive delivery model. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 38(4), 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, E., Roche, T., Wilson, E., & McKenzie, J. W. (2023). Implications of immersive scheduling for student achievement and feedback. Studies in Higher Education, 48(7), 1123–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, E., Roche, T., Wilson, E., & McKenzie, J. W. (2024a). Student perceptions of immersive block learning: An exploratory study of student satisfaction in the Southern Cross Model. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 48(2), 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, E., Roche, T., Wilson, E., Naumann, F., Boyd, W., & Mckenzie, J. W. (2024b). Lessons learned from institution-wide curriculum reform: New and transitioned student feedback on a higher education immersive block model. Southern Cross University Scholarship of Learning and Teaching Paper No 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, E., Roche, T., Wilson, E., Zhang, J., & McKenzie, J. W. (2024c). The success, satisfaction and experiences of international students in an immersive block model. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 21(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, E., Syme, S., & Nieuwoudt, J. E. (2024d). The impact of immersive scheduling on student learning and success in an Australian pathways program. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 61, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfand, D. J. (2013). The social conquest of general education. General Education: A Curricular Commons of the Humanities and Sciences, 62(1), 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornstein, H. A. (2017). Student evaluations of teaching are an inadequate assessment tool for evaluating faculty performance. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1304016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S., & de Main, L. (2025). Quality on the Block. In J. Weldon, & L. Konjarski (Eds.), Block teaching essentials: A practical guide (pp. 139–153). Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L. (2008). The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science, 319(5865), 966–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Koper, N., & Manseau, M. (2009). Generalized estimating equations and generalized linear mixed-effects models for modelling resource selection. The Journal of Applied Ecology, 46(3), 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N., & Horsfall, B. (2010). Accelerated learning: A study of faculty and student experiences. Innovative Higher Education, 35(3), 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.-Y., & Zeger, S. L. (1986). Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika, 73, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, T. (2023). What is the meaning of student success in higher education? Buckingham Journal of Education, 4, 91–102. Available online: https://www.ubplj.org/index.php/TBJE/article/view/2207 (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Lutes, L., & Davies, R. (2018). Comparison of workload for university core courses taught in regular semester and time-compressed term formats. Education Sciences, 8(1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, F., & Saljo, R. (1976). On qualitative differences in learning: Outcome and process. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46(1), 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. E. (2004). Should there be a three-strikes rule against pure discovery learning? American Psychologist, 59(1), 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, T., Weldon, J., & Smallridge, A. (2019). Rebuilding the first year experience, one block at a time. Student Success, 10(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicholas, C., & Marcella, R. (2022). An interactive decision-making model of international postgraduate student course choice. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 34(2), 802–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, J. L., Baron, R., & Zutshi, A. (2015). Transitional experiences of international postgraduate students utilising a peer mentor programme. Educational Research, 57(4), 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moogan, Y. J. (2020). An investigation into international postgraduate students’ decision-making process. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(1), 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R. (2017). First year student conceptions of success: What really matters? Student Success, 8(2), 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, D., & Ramia, G. (2009). Study-work-life balance and the welfare of international students. Labour & Industry, 20(2), 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W. (2001). Akaike’s information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics, 57(1), 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, J. S., Thapa, P., Micheal, S., Dune, T., Lim, D., Alford, S., Mistry, S. K., & Arora, A. (2025). The Impact of a peer support program on the social and emotional wellbeing of postgraduate health students during COVID-19: A qualitative study. Education Sciences, 15(3), 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, H., & Leslie, K. (2025). Postgraduate Psychology students’ perceptions of mental wellbeing and mental health literacy: A preliminary mixed-method case study. Education Sciences, 15(3), 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Pla, A., Reese, L., Arce, C., Balladares, J., & Fiallos, B. (2022). Teaching online: Lessons learned about methodological strategies in postgraduate studies. Education Sciences, 12(10), 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, A. S., Murphy, B. C., Curl, L. S., & Broussard, K. A. (2015). The effect of immersion scheduling on academic performance and students’ ratings of instructors. Teaching of Psychology, 42(1), 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, T. (2017). Assessing the role of digital literacy in English for academic purposes university pathway programs. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 11(1), A71–A87. Available online: https://journal.aall.org.au/index.php/jall/article/view/439 (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Roche, T., Harrington, M., Sinha, Y., & Denman, C. (2016). Vocabulary recognition skill as a screening tool in English-as-a-Lingua-Franca university settings. In Post-admission language assessment of university students. English language education (vol. 6, pp. 159–178). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, T., Sinha, Y., & Denman, C. (2015). Unravelling failure: Belief and performance in English for academic purposes programs in Oman. In R. Al-Mahrooqi, & C. Denman (Eds.), Issues in English education in the Arab world (pp. 159–178). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, T., Wilson, E., & Goode, E. (2022). Why the Southern Cross Model? How one university’s curriculum was transformed. Southern Cross University Scholarship of Learning and Teaching Paper No. 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, T., Wilson, E., & Goode, E. (2024). Immersive learning in a block teaching model: A case study of academic reform through principles, policies and practice. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 21(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, T., Wilson, E., Goode, E., & McKenzie, J. W. (2025). Supporting the academic success of underrecognised higher education students through an immersive block model. Higher Education Research & Development, 44(3), 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovagnati, V., Pitt, E., & Winstone, N. (2022). Feedback cultures, histories and literacies: International postgraduate students’ experiences. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(3), 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarawickrema, G., & Cleary, K. (2021). Block mode study: Opportunities and challenges for a new generation of learners in an Australian university. Student Success, 12(1), 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, Y., Roche, T., & Sinha, M. (2018). Understanding higher education attrition in English-medium programs in the Arab Gulf States: Identifying push, pull and fallout factors at an Omani university. In R. Al-Mahrooqi, & C. Denman (Eds.), English education in Oman (pp. 195–229). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southern Cross University. (2025). Southern Cross University at a glance. Available online: https://www.scu.edu.au/staff/business-intelligence-and-quality-biq/statistics/ (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V. (2017). Through the eyes of students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory and Practice, 19(3), 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R., Webb, O. J., & Cotton, D. R. E. (2021). Introducing immersive scheduling in a UK university: Potential implications for student attainment. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(10), 1371–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vokić, N. P., Bilušić, M. R., & Perić, I. (2021). Work-study-life balance—The concept, its dyads, socio-demographic predictors and emotional consequences. Zagreb International Review of Economics and Business, 24(s1), 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E., Goode, E., & Roche, T. (2025a). Transforming assessment policy: Improving student outcomes through an immersive block model. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 47(2), 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E., Roche, T., & Goode, E. (2025b). Enhancing student success for the ‘new majority’ in higher education through immersive block model learning. Innovations in Education and Teaching International. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E., Roche, T., Goode, E., & McKenzie, J. W. (2025c). Creating the conditions for student success through curriculum reform: The impact of an active learning, immersive block model. Higher Education, 89, 1423–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchester-Seeto, T., Ferns, S. J., Lucas, P., Piggott, L., & Rowe, A. (2024). Intensive Work-Integrated Learning (WIL): The benefits and challenges of condensed and compressed WIL experiences. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 21(2), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T0 | T1 | SCM | T0 to SCM | T1 to SCM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | n (%) | Success Rate (%) | n (%) | Success Rate (%) | n (%) | Success Rate (%) | Change X2(1), p | Change X2(1), p | |

| All | 8381 | 58.7 | 1744 | 73.1 | 4215 | 90.6 | 31.9 *** | 17.5 *** | |

| (100.0%) | (100.0%) | (100.0%) | 1345.9, <0.001 | 304.4, <0.001 | |||||

| Discipline | |||||||||

| Information Technology | 897 | 46.5 | 516 | 78.7 | 1522 | 92.9 | 46.4 *** | 14.2 *** | |

| (10.7%) | (29.6%) | (36.1%) | 660.9, <0.001 | 81.6, <0.001 | |||||

| Engineering | 1572 | 56.1 | 218 | 75.7 | 854 | 94.5 | 38.4 *** | 18.8 *** | |

| (18.8%) | (12.5%) | (20.3%) | 385.6, <0.001 | 72.6, <0.001 | |||||

| Management and Commerce | 5912 | 61.2 | 1010 | 69.7 | 1839 | 86.9 | 25.7 *** | 17.2 *** | |

| (70.5%) | (57.9%) | (43.6%) | 420.9, <0.001 | 124.2, <0.001 | |||||

| Home region | |||||||||

| Africa and Middle East | 87 | 83.9 | 77 | 83.1 | 157 | 89.8 | 5.9 | 6.7 | |

| (1.0%) | (4.4%) | (3.7%) | 1.8, 0.176 | 2.1, 0.144 | |||||

| South America | 59 | 86.4 | 108 | 90.7 | 342 | 98.0 | 11.6 *** | 7.3 ** | |

| (0.7%) | (6.2%) | (8.1%) | 18.5, <0.001 | 11.7, 0.001 | |||||

| North-East Asia | 457 | 74.4 | 154 | 74.7 | 398 | 90.5 | 16.1 *** | 15.8 *** | |

| (5.5%) | (8.8%) | (9.4%) | 36.9, <0.001 | 23.0, <0.001 | |||||

| Southeast Asia | 345 | 82.6 | 62 | 69.4 | 297 | 92.9 | 10.3 *** | 23.5 *** | |

| (4.1%) | (3.6%) | (7.0%) | 15.4, <0.001 | 28.8, <0.001 | |||||

| Southern and Central Asia | 7433 | 56.1 | 1343 | 71.1 | 3021 | 89.6 | 33.5 *** | 18.5 *** | |

| (88.7%) | (77.0%) | (71.7%) | 1072.7, <0.001 | 235.6, <0.001 | |||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 3141 | 73.4 | 716 | 74.3 | 1692 | 91.3 | 17.9 *** | 17.0 *** | |

| (37.5%) | (41.1%) | (40.1%) | 218.1, <0.001 | 122.8, <0.001 | |||||

| Male | 5240 | 49.8 | 1028 | 72.3 | 2523 | 90.1 | 40.3 *** | 17.8 *** | |

| (62.5%) | (58.9%) | (59.9%) | 1184.8, <0.001 | 182.2, <0.001 | |||||

| Age | |||||||||

| 20–24 | 3175 | 49.9 | 247 | 72.9 | 773 | 88.6 | 38.7 *** | 15.7 *** | |

| (37.9%) | (14.2%) | (18.3%) | 381.4, <0.001 | 36.0, <0.001 | |||||

| 25–34 | 4956 | 63.2 | 1344 | 73.0 | 3133 | 91.5 | 28.3 *** | 18.5 *** | |

| (59.1%) | (77.1%) | (74.3%) | 801.3, <0.001 | 267.1, <0.001 | |||||

| 35+ | 250 | 79.6 | 153 | 74.5 | 309 | 86.4 | 6.8 * | 11.9 ** | |

| (3.0%) | (8.8%) | (7.3%) | 4.6, 0.032 | 10.0, 0.002 | |||||

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference: T0 | ||||

| SCM | 2.31 * | 1.11–4.82 | 0.025 | |

| SCM*Southern and Central Asia | 1.14 | 0.52–2.46 | 0.746 | |

| SCM*Southeast Asia | 0.67 | 0.23–1.96 | 0.468 | |

| SCM*South America | 3.30 | 0.59–18.56 | 0.175 | |

| SCM*Africa and Middle East | 0.40 | 0.11–1.52 | 0.180 | |

| SCM*Male | 2.15 *** | 1.49–3.10 | <0.001 | |

| SCM*35+ | 0.23 *** | 0.11–0.47 | <0.001 | |

| SCM*25–34 | 0.76 | 0.55–1.04 | 0.083 | |

| SCM*Engineering | 1.53 | 0.94–2.50 | 00.088 | |

| SCM*Information Technology | 2.59 *** | 1.62–4.16 | <0.001 | |

| Reference: T1 | ||||

| SCM | 2.44 * | 1.07–5.55 | 0.033 | |

| SCM*Southern and Central Asia | 0.87 | 0.35–2.21 | 0.753 | |

| SCM*Southeast Asia | 0.98 | 0.32–2.98 | 0.973 | |

| SCM*South America | 1.72 | 0.40–7.29 | 0.463 | |

| SCM*Africa and Middle East | 0.36 | 0.08–1.63 | 0.185 | |

| SCM*Male | 0.97 | 0.63–1.48 | 0.877 | |

| SCM*35+ | 0.49 | 0.20–1.21 | 0.122 | |

| SCM*25–34 | 1.12 | 0.69–1.80 | 0.646 | |

| SCM*Engineering | 1.53 | 0.83–2.85 | 0.175 | |

| SCM*Information Technology | 1.03 | 0.61–1.72 | 0.918 | |

| Model QIC = 15369.8 | ||||

| Observations = 14,340 | ||||

| Subjects = 3122 | ||||

| Measurements per subject = 1–24 | ||||

| Working correlation matrix (exchangeable) = 0.295 | ||||

| T0 | T1 | SCM | T0 to SCM | T1 to SCM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | n (%) | Agreement (%) | n (%) | Agreement (%) | n (%) | Agreement (%) | Change X2(1), p | Change X2(1), p | |

| All | 2042 | 77.7 | 728 | 83.7 | 2133 | 88.5 | 10.8 *** | 4.8 *** | |

| (100.0%) | (100.0%) | (100.0% | 87.0, <0.001 | 11.3, <0.001 | |||||

| Discipline | |||||||||

| Information Technology | 230 | 73.0 | 204 | 82.4 | 760 | 87.1 | 14.1 *** | 4.7 | |

| (11.3%) | (28.0%) | (35.6%) | 25.8, <0.001 | 3.0, 0.103 | |||||

| Engineering | 346 | 82.7 | 65 | 84.6 | 418 | 93.5 | 10.8 *** | 8.9 * | |

| (16.9%) | (8.9%) | (19.6%) | 22.2, <0.001 | 6.3, 0.012 | |||||

| Management and Commerce | 1466 | 77.2 | 459 | 84.1 | 955 | 87.3 | 10.1 *** | 3.2 | |

| (71.8%) | (63.0%) | (44.8%) | 38.8, <0.001 | 2.7, 0.098 | |||||

| Home region | |||||||||

| Africa, Middle East, and South America | 33 | 78.8 | 107 | 88.8 | 299 | 83.6 | 4.8 | −5.2 | |

| (1.6%) | (14.7%) | (14.0%) | 0.5, 0.482 | 1.7, 0.199 | |||||

| Northeast Asia | 159 | 81.1 | 80.00 | 85.0 | 228.00 | 91.7 | 10.6 ** | 6.7 | |

| (7.8%) | (3.9%) | (4.0%) | 9.4, 0.002 | 2.9, 0.088 | |||||

| Southeast Asia | 161 | 77.6 | 30 | 80.0 | 184 | 88.6 | 11.0 ** | 8.6 | |

| (7.9%) | (4.1%) | (8.6%) | 7.5, 0.006 | 1.7, 0.187 | |||||

| Southern and Central Asia | 1689 | 77.3 | 511 | 82.6 | 1422 | 89.0 | 11.7 *** | 6.4 *** | |

| (82.7%) | (70.2%) | (66.7%) | 72.9, <0.001 | 13.8, <0.001 | |||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 1008 | 77.8 | 359 | 84.4 | 965 | 86.9 | 9.1 *** | 2.5 | |

| (49.4%) | (49.3%) | (45.2%) | 28.4, <0.001 | 1.4, 0.232 | |||||

| Male | 1034 | 77.6 | 369 | 82.9 | 1168 | 89.7 | 12.1 *** | 6.8 *** | |

| (50.6%) | (50.7%) | (54.8%) | 60.4, <0.001 | 12.4, <0.001 | |||||

| Age | |||||||||

| 20–24 | 688 | 77.2 | 80 | 88.8 | 360 | 84.2 | 7.0 * | −4.6 | |

| (33.7%) | (11.0%) | (16.9%) | 7.1, 0.010 | 1.1, 0.299 | |||||

| 25–34 | 1268 | 77.5 | 561 | 84.1 | 1581 | 90.2 | 12.7 *** | 6.1 *** | |

| (62.1%) | (77.1%) | (74.1%) | 86.5, <0.001 | 15.1, <0.001 | |||||

| 35+ | 86 | 83.7 | 87 | 75.9 | 192 | 82.3 | −1.4 | 6.4 | |

| (4.2%) | (12.0%) | (9.0%) | 0.1, 0.771 | 1.6, 0.211 | |||||

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference: T0 | ||||

| SCM | 1.89 ** | 1.24–2.88 | 0.003 | |

| SCM*35+ | 0.42 | 0.16–1.08 | 0.072 | |

| SCM*25–34 | 1.24 | 0.76–2.01 | 0.384 | |

| Reference: T1 | ||||

| SCM | 0.63 | 0.30–1.34 | 0.234 | |

| SCM*35+ | 1.40 | 0.40–4.93 | 0.599 | |

| SCM*25–34 | 2.03 | 0.88–4.71 | 0.097 | |

| Model QIC = 4354.1 | ||||

| Observations = 4903 | ||||

| Subjects = 1328 | ||||

| Measurements per subject = 1–14 | ||||

| Working correlation matrix (exchangeable) = 0.179 | ||||

| Characteristic | No. | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Home country | China | 3 | 33.3% |

| Brazil | 1 | 11.1% | |

| Fiji | 1 | 11.1% | |

| Nepal | 1 | 11.1% | |

| Peru | 1 | 11.1% | |

| Philippines | 1 | 11.1% | |

| United States | 1 | 11.1% | |

| Gender | Female | 7 | 77.8% |

| Male | 2 | 22.2% | |

| Course | Master of Social Work | 3 | 33.3% |

| Master of Business Administration | 1 | 11.1% | |

| Master of Information Technology | 1 | 11.1% | |

| Master of Nursing | 1 | 11.1% | |

| Master of Osteopathic Medicine | 1 | 11.1% | |

| Master of Professional Accounting | 1 | 11.1% | |

| Master of Teaching | 1 | 11.1% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goode, E.; Roche, T.; Wilson, E.; Zhang, J. The Impact of an Immersive Block Model on International Postgraduate Student Success and Satisfaction: An Australian Case Study. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111425

Goode E, Roche T, Wilson E, Zhang J. The Impact of an Immersive Block Model on International Postgraduate Student Success and Satisfaction: An Australian Case Study. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111425

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoode, Elizabeth, Thomas Roche, Erica Wilson, and Jacky Zhang. 2025. "The Impact of an Immersive Block Model on International Postgraduate Student Success and Satisfaction: An Australian Case Study" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111425

APA StyleGoode, E., Roche, T., Wilson, E., & Zhang, J. (2025). The Impact of an Immersive Block Model on International Postgraduate Student Success and Satisfaction: An Australian Case Study. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111425