Moving Beyond Eurocentric Notions of Intellectual Safety: Insights from an Anti-Racist Mathematics Institute

Abstract

1. The Case for Intellectual Safety

2. Learning Environments Beyond Inclusion

2.1. The Need for Culturally Responsive and Anti-Racist Education

2.2. Equity and Exclusion in Math Education

2.3. Theoretical Framework

- How can intellectual safety be reconceptualized to center the experiences and lived realities of BIPOC students?

- In what ways (if any) do secondary (8th–12th grade) students, from racially and socially marginalized backgrounds experience intellectual safety?

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Context

3.2. Participants

3.3. Methodology

3.3.1. Researcher Positionality

3.3.2. Attention to Salience of Racism

3.3.3. Counter-Storytelling

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis

4. What Emerged from the Work: Insights from Scholar’s Experiences

Edward’s comment in this instance showcased that they were proud of the opportunities and the work that they were doing. This was similar across other scholars’ comments where they had felt a sense of accomplishment, growth, or self-validation (which we argued was qualitatively different than their individual strengths being noticed by others. We argue similarly for the codes Clarity/Transparency and Listened To. Across both HD (hair discrimination) and WG (wage gap) groups, scholars repeatedly emphasized that they felt listened to, especially in group settings where their peers asked for input or when scholars felt “seen” as whole people, especially when their personal experiences were acknowledged. For instance, Brooklyn mentions, “when I’m working with my group, I felt like they were actually listening to me and that they like my ideas.” while Isaach stated that “The one time I felt cared about or heard was when we went over the class work and I spoke about one of my experiences which felt good.” There were other instances of scholars feeling like their voices were being heard and respected in this space, so much so that we developed a code for this. From our data analysis, of the 515 scholar journal entries, about 1/4 of the codes were labeled as one of the emergent codes not initially presented in our initial conceptualization. Based on these codes, we realized the need to reorganize them to better reflect the emerging themes in scholars’ experiences. This included clarifying the contextual relationship between scholars and teachers, distinguishing engagement related codes tied to scholars’ intrinsic motivation and the factors that best support it.I think that that really ties into how my ideas right? I felt valued like in many, many different ways, really like whether it be like when we were like…even like, before we started working in groups, we were advocating for our topics. I felt like I had a voice, and I think that it felt like I was like, my ideas were actually important. And I was like able TO really, you know, add voice my opinion, and also like in groups who allows it play to our strengths, and also like after, like groups, when we’re like presenting, or even just looking at other groups, work like helping them in a sense, right? All of those aspects right? I felt empowered in unique ways… I think I was also able to like, suggest, like, Hey, do you think we should do this on the website. Should we do this? And like I was, I think that I was able to like contribute, because, like… like, I was like playing to my strengths, but also like I think that… you know, like, with the website, too, like, since we were kind of splitting it up into parts. And we were working on it at different times. I got a chance to do like couple of like the things, and I think that like helped. And it felt like because of the you know, roles being distributed right and kind of us like identifying those roles at the beginning of the project. We were all kind of able to have like somewhat of like an equal, contribute contribution to the project.

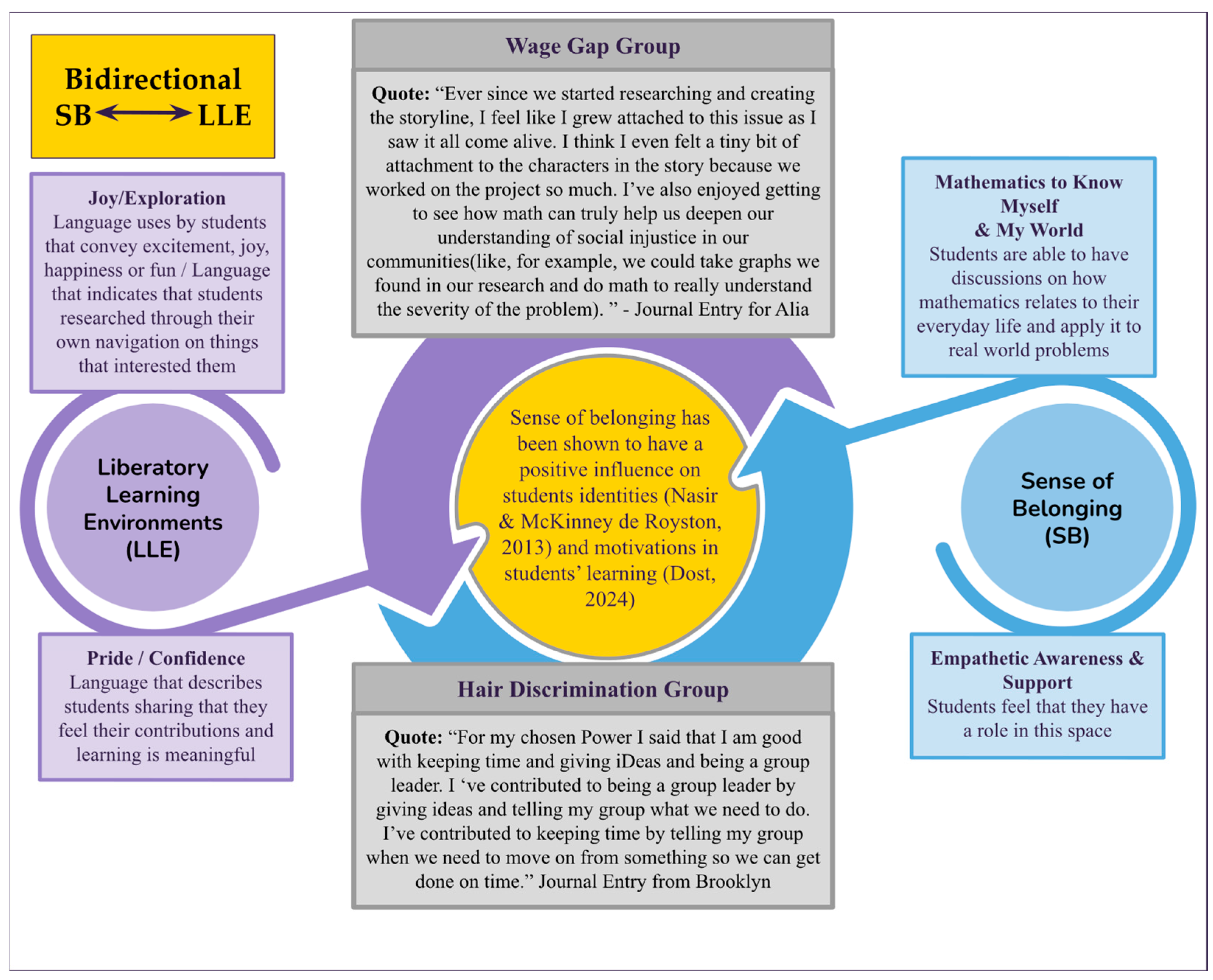

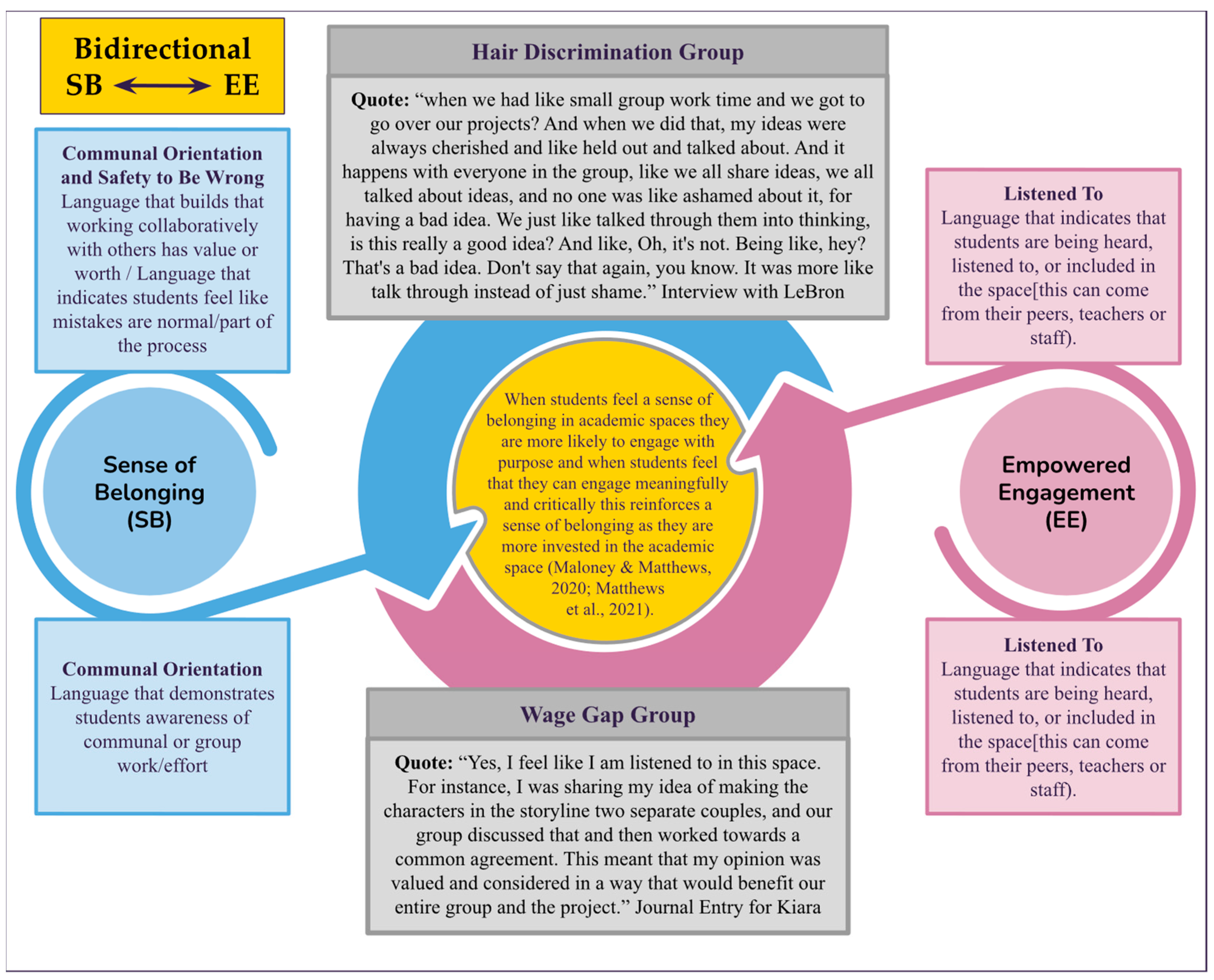

4.1. Reconceptualization: A Justice-Oriented Approach to Intellectual Safety

4.2. Evidence of Belonging, Empowerment Engagement, and Liberatory Learning Experiences: Scholar’s Experiences of Intellectual Safety

4.2.1. Sense of Belonging

For the HD (hair discrimination) group, scholars experienced many instances of safety to be wrong, particularly the younger scholars in the group. For instance in an interview with Brooklyn and Nina, both mention that their peers supported them in their learning process:“using physical and just like drawing it out. Especially with,… which can really help my generation, like my age group. Since we, we’ve gotten more where we need like that physical thing instead of like looking at it. Like we need to be more engaged like movement? Wise?”

Nina: [About feeling comfortable making mistakes] Because like, I don’t think anyone here is like gonna be like mean or anything. Most of these people here are like older than me, and they’re more mature. So I don’t think they’ll be like that. They never been like that towards me or anything, so.

For more student examples of sense of belonging instances, see the Supplementary Materials Tables S1–S7.Brooklyn: Yeah, they’d like, I’m also like one of the younger ones, but they, since they’re older they’re nice. And then also because when we mess up we just like we just go back and fix it, and then we don’t make a big deal out of it, because other people would. But from what I’ve seen in a group, nobody really would do that.

4.2.2. Liberatory Learning Experiences

Additionally, Alia recounts:“My topic is hair discrimination at first I didn’t know much but the more and more I researched about it I really knew what I was doing and I was able to elaborate more on what I was thinking more to my peers.”

In interviews with scholars and from instances in their journals, all scholars reported that they had felt that their culture and identity were affirmed in this space. Scholars contributed these feelings to most of the institute being people of color, connecting their projects to their lived experiences, normalizing that injustices occur, and being understanding about learning about these topics. For instance, Brooklyn stated that she feels valued in this space because people did not look at her differently because of her skin. Isaach reflects on his experience at a predominantly white school and how being in this space made him feel valued because “there’s other people out there that have the same personality, looks, and everything.” These feelings contributed to feeling a sense of positive cultural distinctiveness. Edward mentions, “I was thinking of asking my parents about their experience with the wage gap. I wanted to implement their knowledge and ideas into my project” when reflecting on how to connect her personal story to her social justice topic. Altogether, scholars encountered opportunities to connect their experiences, interests, identities, and cultural backgrounds to learning in this environment contributing to a portion of intellectual safety. For more student examples of liberatory learning experience instances, see the Supplementary Materials Tables S8–S11.“One thing I already knew a little bit about and learned more about today in terms of equity is like the differences in opinion on equality and equity coexisting. Equality is important when discussing rights, however, equity is important when we are talking about resources provided to different people. I plan to use this in my research when researching racial wage gaps. I plan on diving into what would be more just, equality or equity in pay. I think that maybe equity is not always better than equality.”

4.2.3. Empowered Engagement

The HD (hair discrimination) additionally felt that the math component of the project was the most difficult to incorporate in their group, with one particular scholar requesting a math expert be added to the institute and two scholars expressing initial concern over understanding high school standards as younger scholars. For example, Brooklyn notes:“I would like to make steady progress on our project by ensuring that all the content is organized on the slideshow by the end of the week. I feel like having “tasks” for the day so we know what we need to get done to stay on track can help me not forget about what things to include.”

Additionally, many of our scholars reported the change in perspective of the severity of the social injustices they investigated. They had moments of determination and reflection while exploring various aspects of the project (researching, writing, conceptualizing math problems, coming up with solutions to social justice issues, etc.). Four out of five scholars in the HD (hair discrimination) group noted not realizing sooner the severity of the issue and how antiblack school/work policies were embedded in everyday life. Nina expressed her motivations stemming from her discussions with her math coach: “When one of my coaches helped us and told us about a guy who was forced to cut his dreads for the school match and that really is what motivated me to do this project.” Nina shared a desire to work and explore her chosen systemic injustice and ended up feeling a sense of accomplishment in her work. From the WG (wage gap) group, we had four out of six scholars reporting similar sentiments with the research process and institute. For example Kiara reflects on providing actionable tasks to the broader audience:“Like with the math problem, like I didn’t understand it because it’s high school level, and I’m going into high school. So I’m like, I don’t understand it. So like now they’re [group members] helping me understand it and all that”

Within empowered engagement, the codes that showed up the least were that of intellectual risk and critical inquiry. With intellectual risk we make the distinction that scholars need to actively engage in risk taking where they challenge their preconceived ideas, push beyond their current knowledge, and work through ambiguous tasks through trial-and-error learning. In one instance, Brooklyn showcased this when she talked about not understanding a math problem but continuing to work on it with the help of her peers, pushing past what she believed were math concepts that were more advanced than where she was currently. With critical inquiry, scholars expressed this through referencing diverse perspectives with contrasting ideas and synthesizing what they have learned. For example, in the WG (wage gap) group, Mark and Alia mentioned reaching out to people they know (parents or other coaches) to gain a better understanding of how wage gaps impact the world through people they are comfortable around. Within this theme, scholars challenged the power structures in the environment while validating their knowledge in tangible ways. For more student examples of empowered engagement, see the Supplementary Materials Tables S12–S16.“For the wage gap project, we outlined some broad solutions such as encouraging students to research wage inequality further, have students find their own examples of wage inequality and present their findings, challenge students to think critically about the causes and effects of wage inequality, and inspire students to advocate for fair pay and equal opportunities for all. In addition to this, our group decided to make a website as we thought it would be accessible to everyone on the internet.”

4.3. Scholar’s Experiences on the Interdependence of Belonging, Empowered Engagement, and Liberatory Learning Expereinces

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications and Recommendations

5.2. Limitations and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CMJ | Center for Measurement Justice |

| BCI | Belonging Centered Instructional Protocol |

| NCTM | National Council of Teachers of Mathematics |

References

- Aldana, A., & Richards-Schuster, K. (2021). Youth-led antiracism research: Making a case for participatory methods and creative strategies in developmental science. Journal of Adolescent Research, 36(6), 654–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, J. (2008). A talk to teachers. Teachers College Record, 110(14), 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battey, D., & Leyva, L. A. (2016). A framework for understanding whiteness in mathematics education. Journal of Urban Mathematics Education, 9(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeney, A. M. (2005). Antiracist pedagogy: Definition, theory, and professional development. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy, 2(1), 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2015). The structure of racism in color-blind, “post-racial” America. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(11), 1358–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brayboy, B. M. J. (2005). Toward a tribal critical race theory in education. The Urban Review, 37(5), 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricker, L. A., Reeve, S., & Bell, P. (2014). ‘She has to drink blood of the snake’: Culture and prior knowledge in science|health education. International Journal of Science Education, 36(9), 1457–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese Barton, A., & Tan, E. (2020). Beyond equity as inclusion: A framework of “rightful presence” for guiding justice-oriented studies in teaching and learning. Educational Researcher, 49(6), 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Call, C. M. (2007). Defining intellectual safety in the college classroom. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 18(3), 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, T. K. (2013). You can’t erase race! Using CRT to explain the presence of race and racism in majority white suburban schools. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 34(4), 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhuon, V., & LeBaron Wallace, T. (2012). Creating connectedness through being known: Fulfilling the need to belong in U.S. high schools. Youth & Society, 46, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway Iv, B. M., Deen, L. I., Raygoza, M. C., Ruiz, A., Staley, J. W., & Thanheiser, E. (2023). Middle school mathematics lessons to explore, understand, and respond to social injustice. Corwin. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C. H. F., Harris, J. C., Stokes, S., & Harper, S. R. (2019). But is it activist?: Interpretive criteria for activist scholarship in higher education. The Review of Higher Education, 42(5), 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, N. R., Vossoughi, S., & Smith, J. F. (2020). Learning from below: A micro-ethnographic account of children’s self-determination as sociopolitical and intellectual action. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 24, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCuir, J. T., & Dixson, A. D. (2004). “So when it comes out, they aren’t that surprised that it is there”: Using critical race theory as a tool of analysis of race and racism in education. Educational Researcher, 33(5), 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- DeNicolo, C., Yu, M., Crowley, C., & Gabel, S. (2017). Reimagining critical care and problematizing sense of school belonging as a response to inequality for immigrants and children of immigrants. Review of Research in Education, 41, 500–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemer, M. A., Frisby, M. B., Marchand, A. D., & Bardelli, E. (2024). Illustrating and enacting a critical quantitative approach to measurement with MIMIC models. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 18, 366–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dost, G. (2024). Students’ perspectives on the ‘STEM belonging’ concept at A-level, undergraduate, and postgraduate levels: An examination of gender and ethnicity in student descriptions. International Journal of STEM Education, 11(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, A., Dahl, L. S., Stipeck, C., & Mayhew, M. J. (2020). A critical quantitative analysis of students’ sense of belonging: Perspectives on race, generation status, and collegiate environments. Journal of College Student Development, 61(2), 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th ed). Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Givens, J. R., & Ison, A. (2023). Toward new beginnings: A review of native, white, and black American education through the 19th century. Review of Educational Research, 93(3), 319–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D. L., Hope, E. C., & Matthews, J. S. (2018). Black and belonging at school: A case for interpersonal, instructional, and institutional opportunity structures. Educational Psychologist, 53(2), 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R. (2012). Context matters: How should we conceptualize equity in mathematics education? In Equity in discourse for mathematics education: Theories, practices, and policies (pp. 17–33). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R. (2013). The sociopolitical turn in mathematics education. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 44, 37–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutstein, E. (2003). Teaching and learning mathematics for social justice in an urban, Latino school. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 34(1), 37–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetti, B. J., & Williams, W. O. (1996). Gender, text, and discussion: Examining intellectual safety in the science classroom. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 33(1), 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartlep, N. D., & Xiong, B. V. (2018). The Hmong archives as a community resource for social studies educators in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Educational Foundations, 31, 118–149. [Google Scholar]

- Kokka, K. (2022). Toward a theory of affective pedagogical goals for social justice mathematics. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 53(2), 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1998). Just what is critical race theory and what’s it doing in a nice field like education? International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 11(1), 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2000). Racialized discourses and ethnic epistemologies. In Handbook of qualitative research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot, S. L. (1986). On goodness in schools: Themes of empowerment. Peabody Journal of Education, 63(3), 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, N. (2018). Culture and ideology in mathematics teacher noticing. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 97, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison, D. (2005). Critical ethnography: Method, ethics, and performance. Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, T., & Matthews, J. S. (2020). Teacher care and students’ sense of connectedness in the urban mathematics classroom. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 51(4), 399–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D. B. (2019). Equity, inclusion, and antiblackness in mathematics education. Race Ethnicity and Education, 22(4), 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D. B., Groves Price, P., & Moore, R. (2019). Refusing systemic violence against black children. In J. Davis, & C. C. Jett (Eds.), Critical race theory in mathematics education (1st ed., pp. 32–55). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J., Gray, D. L., Lachaud, Q., McElveen, T., Chen, X.-Y., Victor, T., Okai, E., Boomhower, K., Wu, J., & Cha, E. (2021). Belonging-centered instruction: An observational approach toward establishing inclusive mathematics classrooms. OSF. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michigan Department of Education. (2018). Michigan K-12 standards for mathematics. Michigan Department of Education. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/mde/-/media/Project/Websites/mde/Literacy/Content-Standards/Math_Standards.pdf?rev=1e793e2b1e314e4fa1abc754251b5dc9&hash=E928B99608A2C6642EA3E19E67CCCD39 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Milner, H. R. (2007). Race, culture, and researcher positionality: Working through dangers seen, unseen, and unforeseen. Educational Researcher, 36(7), 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M. E., Vega, D. M., Wiens, K. M., & Caporale, N. (2020). Connecting theory to practice: Using self-determination theory to better understand inclusion in STEM. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 21(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, N., & McKinney de Royston, M. (2013). Power, identity, and mathematical practices outside and inside school. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 44, 264–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, J., & Lipton, M. (2003). Teaching to change the world. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1609406919899220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, N. A., & Ruwe, D. (2021). Black English and mathematics education: A critical look at culturally sustaining pedagogy. Teachers College Record, 123(10), 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overby, A., Constance, J., & Quenzer, B. (2022). “Reimagining art education”: Moving toward culturally sustaining pedagogies in the arts with funds of knowledge and lived experiences. Art Education, 75(1), 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, R., Hong, J., Engler, C., & King, C. (2016). A study of the effectiveness of the gifts of the seven directions alcohol prevention model for native Americans: Culturally sustaining education for native American adolescents. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 47, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, D. E. (2004). Intellectual safety, moral atmosphere, and epistemology in college classrooms. Journal of Adult Development, 11(2), 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, D. W. (2008). Negotiating sociocultural discourses: The counter-storytelling of academically (and mathematically) successful African American male students. American Educational Research Journal, 45(4), 975–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayhorn, T. L. (2023). Analyzing the short-term impact of a brief web-based intervention on first-year students’ sense of belonging at an HBCU: A quasi-experimental study. Innovative Higher Education, 48(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachine, A. R., Bird, E. Y., & Cabrera, N. L. (2016). Sharing circles: An indigenous methodological approach for researching with groups of indigenous peoples. International Review of Qualitative Research, 9(3), 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., Jackson, D., Freeman-Green, S., Kamuru, J., & Driver, M. (2023). Integrating culturally sustaining pedagogy and evidence-based practices to support students with learning disabilities in a social justice mathematics lesson. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 55(5), 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. L., Hirschi, Q., Sublett, K. V., Hulleman, C. S., & Wilson, T. D. (2020). A brief social belonging intervention improves academic outcomes for minoritized high school students. Motivation Science, 6(4), 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodriguez, J.A.; Randall, J. Moving Beyond Eurocentric Notions of Intellectual Safety: Insights from an Anti-Racist Mathematics Institute. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111424

Rodriguez JA, Randall J. Moving Beyond Eurocentric Notions of Intellectual Safety: Insights from an Anti-Racist Mathematics Institute. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111424

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodriguez, Jennifer Aracely, and Jennifer Randall. 2025. "Moving Beyond Eurocentric Notions of Intellectual Safety: Insights from an Anti-Racist Mathematics Institute" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111424

APA StyleRodriguez, J. A., & Randall, J. (2025). Moving Beyond Eurocentric Notions of Intellectual Safety: Insights from an Anti-Racist Mathematics Institute. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111424