Connecting Beliefs and Practice: Graduate Students’ Approaches to Theoretical Integration and Equitable Literacy Teaching

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Conceptual Framework and Literature Review

1.2. Summary and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Collection Methods

2.2. Data Analysis Process

3. Results

3.1. Research Question One

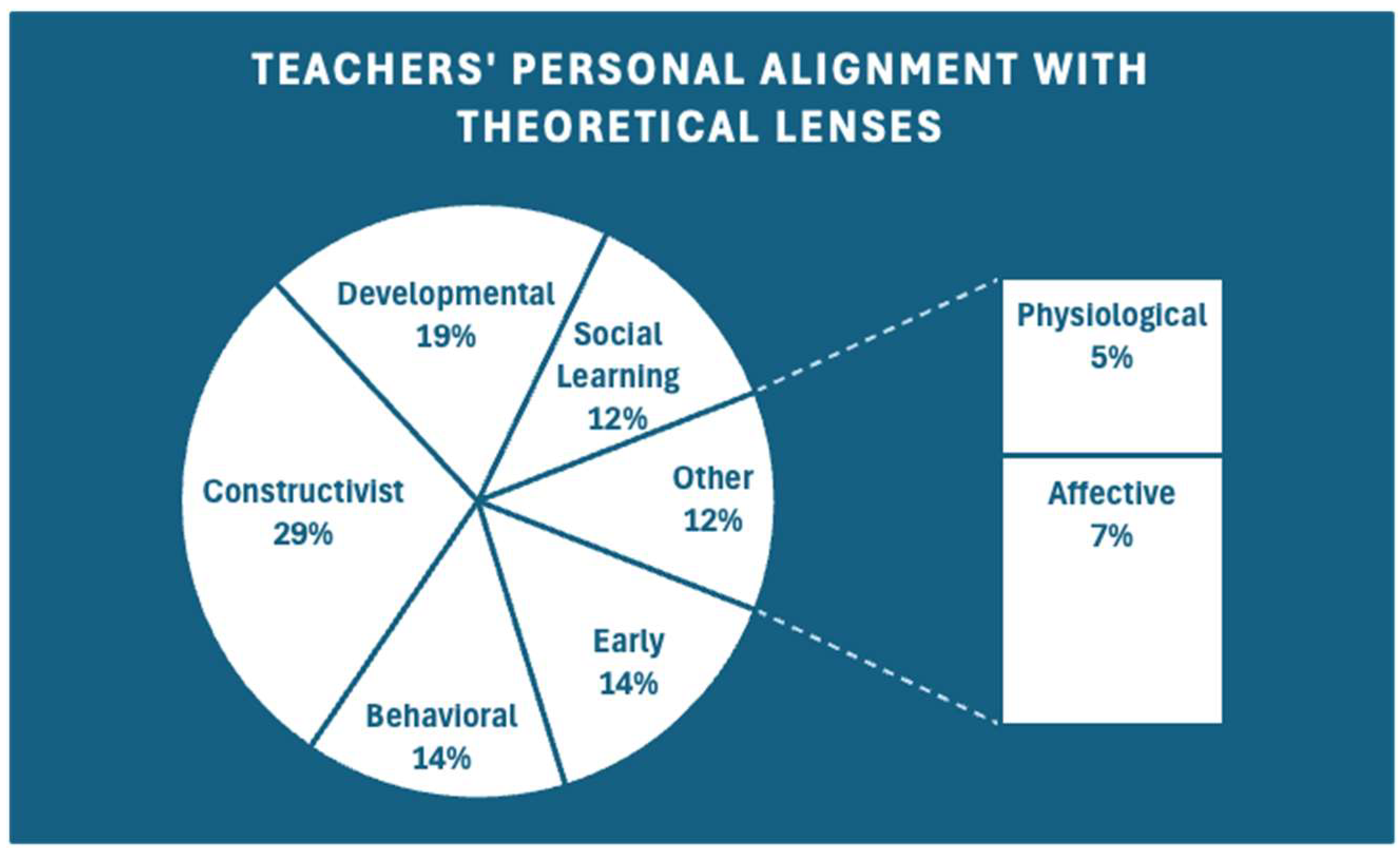

3.2. Research Question Two

3.2.1. Theoretical Pluralism

3.2.2. Differentiated, Development-Based Instruction

3.2.3. Culturally Responsive Literacy Connections

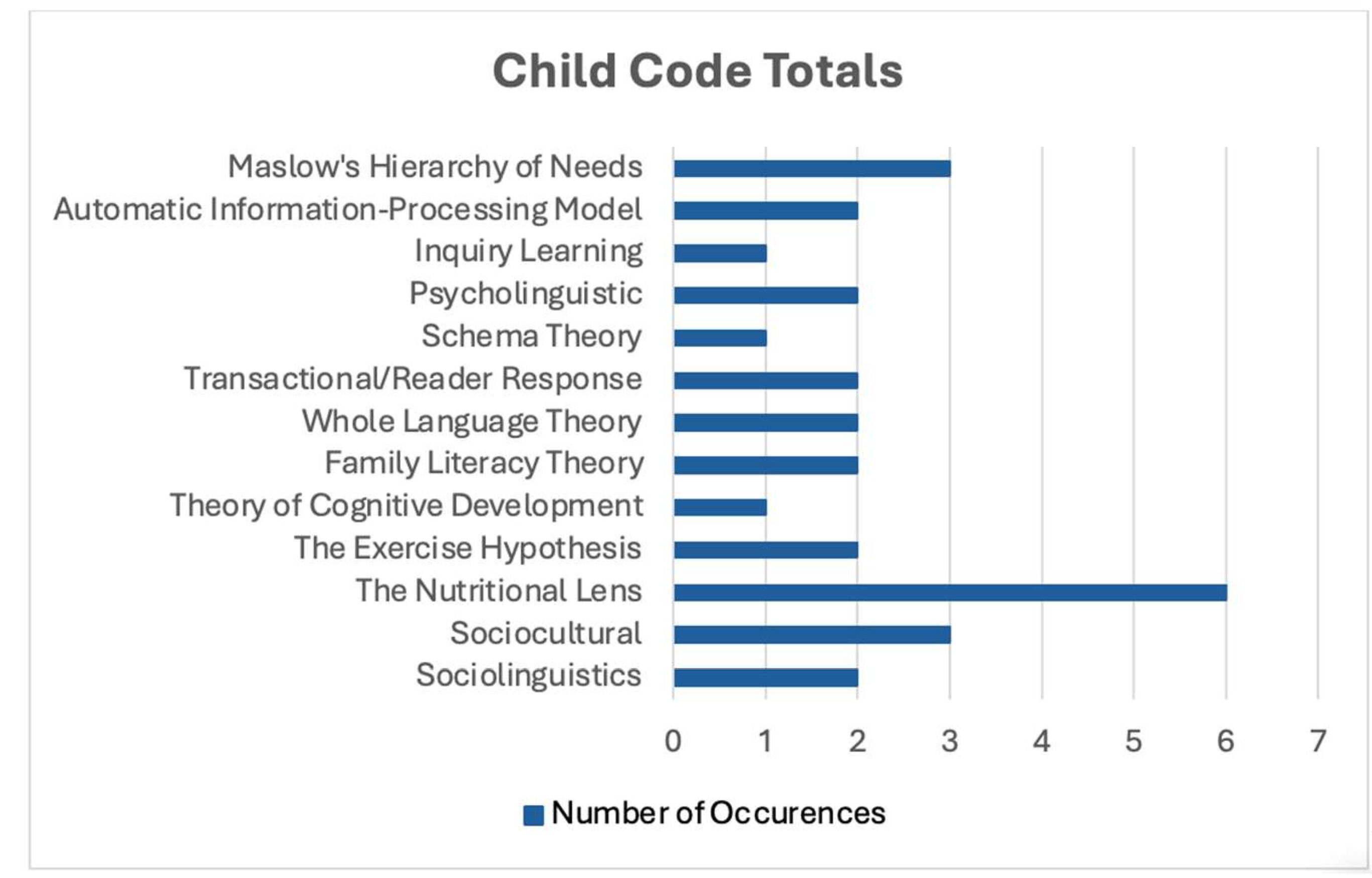

3.3. Quantification as a Descriptive Tool

4. Discussion

This educator bridges theoretical divides with insight. Constructivist elements, such as literature circles, think-alouds, and collaborative meaning-making, where students build on each other’s ideas, are clearly explained. What is particularly discerning is how they have addressed the potential risk that some students might withdraw out of fear of being wrong, which could hinder collaborative knowledge construction. Additionally, their use of Behavioral principles is more nuanced than traditional Behaviorism. Instead of depending on external rewards for correct answers, they emphasize “rewarding” participation and effort. This creates a positive reinforcement cycle that supports the Constructivist aim of active engagement. Connecting to phonics lessons is effective because it aligns with research demonstrating the success of behavioral methods in phonics instruction, where the systematic, sequential presentation of phonological and phonics components supports structured literacy teaching.Another way I see the Constructivist theory in play in my own classroom is using literature circles and partner reading. We are constantly thinking aloud, re-wording others’ answers/explanations and building on others’ thinking as well. It’s very community-based, everyone is involved and most importantly, I feel as though everyone is learning something, be that from the text or from someone else. This is where I align with the Behavioral lens. Students are motivated to answer questions or be more involved with the activity when the stress of not having to be “right” is taken away, but also celebrating everyone’s participation. Although a student’s answer may be incorrect, as a group we can scaffold one another and celebrate/“reward” the students for trying. I see this the most during phonics lessons.

Drawing on their knowledge of students’ early reading development, this educator described how they combined it with their belief in the power of children’s natural interest and curiosity. The Unfoldment lens, characterized by its child-centered focus and recognition of innate language development processes, aligns conceptually with Emergent Literacy’s developmental perspective because both recognize that literacy develops in predictable patterns while honoring individual differences. However, a notable tension exists, as Emergent Literacy involves deliberate scaffolding and “appropriate language experiences,” which is more structured than pure Unfoldment theory might indicate. This educator uses developmental knowledge to guide when and how to intervene naturally.The Unfoldment lens in the classroom promotes daily discussions throughout the day, and following children’s lead helps their language skills unfold naturally. In addition, the Emergent Literacy lens allows me to know what level of language development my students are in and provide appropriate language experiences to continue their vocabulary growth.

4.1. Future Research Directions

4.2. Limitations of the Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Research Questions | Source/ Participants | Data Collection | Data Analysis Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| RQ1. How do graduate students generally connect teaching practices and theoretical lenses or theories in their Reading Matrix assignments? |

|

|

|

| RQ2. Which lenses on reading do graduate students personally align to within their Personal Lens on Reading assignment (e.g., behavioral, constructivist, developmental, affective, social learning, cognitive processing, etc.)? |

|

|

|

| Research Question | RQ1. How do graduate students generally connect teaching practices and theoretical lenses or theories in their Reading Matrix assignments? Source: Reading Matrix Assignment Coding: Descriptive Teaching Practices | |

| Theoretical Lenses (root codes) | Models/Theories (child codes) | Teacher Classroom Literacy Practices |

| Chapter 2: Early Lenses | Associationism |

|

| Mental Discipline Theory |

| |

| Structuralism |

| |

| Unfoldment |

| |

| Chapter 3: Behavioral | Classical Conditioning |

|

| Connectionism |

| |

| Operant Conditioning |

| |

| Chapter 4: Constructivist | Inquiry |

|

| Transactional |

| |

| Schema |

| |

| Psycholinguistic |

| |

| Metacognitive |

| |

| Whole Language Theory |

| |

| Chapter 5: Developmental | Stage Models |

|

| Theory of Literacy Development |

| |

| Theory of Cognitive Development |

| |

| Family Literacy Theory |

| |

| Chapter 6: Physiological | Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs |

|

| Triune Brain |

| |

| The Nutritional Lens |

| |

| Sleep-Dependent Memory Consolidation |

| |

| Exercise Hypothesis |

| |

| Chapter 7: Affective | Attachment Theory |

|

| Engagement Theory |

| |

| Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs |

| |

| Student–Teacher Relationships |

| |

| Chapter 8: Social Learning |

| |

| Social Constructivism |

| |

| Social learning (or cognitive) theory |

| |

| Sociocultural |

| |

| Sociolinguistics |

| |

| Chapter 9: Cognitive-Processing | Automatic Information-Processing Model |

|

| ||

| Gough’s Model |

| |

| Phonological-Core Variable Difference Model |

| |

References

- Aubrey, K., & Riley, A. (2022). Understanding and using educational theories. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Bleukx, N., Denies, K., Van Keer, H., & Aesaert, K. (2024). The interplay between teacher beliefs, instructional practices, and students’ reading achievement: National evidence from PIRLS 2021 using path analysis. Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 12(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comstock, M., Litke, E., Hill, K. L., & Desimone, L. M. (2023). A culturally responsive disposition: How professional learning and teachers’ beliefs about and self-efficacy for culturally responsive teaching relate to instruction. AERA Open, 9, 23328584221140092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedoose. (2016). Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data (Version 7.0.23). Socio Cultural Research Consultants, LLC. Available online: www.dedoose.com (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- DeFord, D. E. (1985). Validating the construct of theoretical orientation in reading instruction. Reading Research Quarterly, 20(3), 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott-Johns, S. (2005). Theoretical orientations to reading and instructional practices of eleven grade five teachers (Order No. NR12838). ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (305363619). Available online: http://search.proquest.com.libproxy.nau.edu/dissertations-theses/theoretical-orientations-reading-instructional/docview/305363619/se-2 (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Filderman, M. J., Didion, L., Austin, C. R., Payne, B., Silvert, C., & Wexler, J. (2025). Teacher professional development for reading: A review of the state of the research. Reading Research Quarterly, 60(4), e70054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floden, R. E. (2009). Empirical research without certainty. Educational Theory, 59(4), 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M. P., Bottiani, J. H., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2024). Assessing teachers’ culturally responsive classroom practice in PK–12 schools: A systematic review of teacher-, student-, and observer-report measures. Review of Educational Research, 94(5), 743–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes-Alpiste, M., Molas-Castells, N., Rubio Hurtado, M. J., & Martínez-Olmo, F. (2023). The creation of situated boundary objects in socio-educational contexts for boundary crossing in higher education. Education Sciences, 13(9), 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, A. P., & Jiménez, R. T. (2021). The science of reading: Supports, critiques, and questions. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S7–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisham, D. L. (2000). Connecting theoretical conceptions of reading to practice: A longitudinal study of elementary school teachers. Reading Psychology, 21(2), 145–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote-Garcia, S., & Ortlieb, E. (2023). What’s hot in literacy 2023: The ban on books and diversity measures. Literacy Research and Instruction, 63(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harell, K. F. (2019). Deliberative decision-making in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, M. A., & Richards, K. A. R. (2018). A practical guide to collaborative qualitative data analysis. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 37(2), 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindman, A. H., Morrison, F. J., Connor, C. M., & Connor, J. A. (2020). Bringing the science of reading to preservice elementary teachers: Tools that bridge research and practice. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1), S197–S206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B. (2021). Advancing the science of teaching reading equitably. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S69–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, K. F., & McGinty, A. S. (2024). Exploring teachers’ reading knowledge, beliefs and instructional practice. Journal of Research in Reading, 47(1), 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketner, C. S., Smith, K. E., & Parnell, M. K. (1997). Relationship between teacher theoretical orientation to reading and endorsement of developmentally appropriate practice. The Journal of Educational Research, 90(4), 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. H. (2013). Content analysis—3rd edition: An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kucer, S. B. (2014). Dimensions of literacy: A conceptual base for teaching reading and writing in school settings. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kushki, A., & Nassaji, H. (2024). L2 reading assessment from a sociocultural theory perspective: The contributions of dynamic assessment. Education Sciences, 14(4), 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lare, C., & Silvestri, K. N. (2023). Reflecting on and embracing the complexity of literacy theories in practice. Language and Literacy Spectrum, 33(1), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Many, J. E., Howard, F., & Hoge, P. (2002). Epistemology and preservice teacher education: How do beliefs about knowledge affect our students’ experiences? English Education, 34(4), 302–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass, Cop. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, S., Hu, X., Kuo, L.-J., Jouhar, M., Xu, Z., & Lee, S. (2018). Vocabulary instruction: A critical analysis of theories, research, and practice. Education Sciences, 8(4), 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D. (2014). Pragmatism as a paradigm for social research. Qualitative Inquiry, 20, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, K. T., Peele, R., Elson, K., Arce, A., Sumner, E., & Polson, B. (2025). Toward a cultural sustenance view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 60, e583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council on Teacher Quality. (2024). Five policy actions to strengthen implementation of the science of reading. The Joyce Foundation. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED639582 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Pearson, P. D. (2001). Life in the radical middle: A personal apology for a balanced view of reading. In R. Flippo (Ed.), Reading researchers in search of common ground (pp. 78–83). International Reading Association. [Google Scholar]

- Readence, F. E., & Barone, D. M. (2000). Envisioning the future of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 35(1), 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinking, D., & Yaden, D. B. (2021). Do we need more productive theorizing? A commentary. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(3), 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailors, M., Hoffman, J. V., David Pearson, P., McClung, N., Shin, J., & Phiri, L. M. (2014). Supporting change in literacy instruction in Malawi. Reading Research Quarterly, 49(2), 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld, A. H. (2006). Notes on the educational Steeplechase: Hurdles and jumps in the development of research-based mathematics instruction. In M. A. Constas, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Translating theory and research into educational practice: Developments in content domains, large scale reform, and intellectual capacity (pp. 9–30). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S. (2021, October 13). More states are making the ‘Science of Reading’ a policy priority. Education Week. Available online: https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/more-states-are-making-the-science-of-reading-a-policy-priority/2021/10 (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Shaw, D. M., Dvorak, M. J., & Bates, K. (2007). Promise and possibility—Hope for teacher education: Pre-service literacy instruction can have an impact. Reading Research and Instruction, 46(3), 223–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R., Snow, P., Serry, T., & Hammond, L. (2023). Elementary teachers’ perspectives on teaching reading comprehension. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 54(3), 888–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squires, D., & Bliss, T. (2004). Teacher visions: Navigating beliefs about literacy learning. The Reading Teacher, 57(8), 756–763. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, D., Morgan, D. N., DeFord, D. E., Donnelly, A., Hamel, E., Keith, K. J., Brink, D. A., Johnson, R., Seaman, M., Young, J., Gallant, D. J., Hao, S., & Leigh, S. R. (2011). The impact of literacy coaches on teachers’ beliefs and practices. Journal of Literacy Research, 43(3), 215–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, R. J., & Pearson, P. D. (2024). Fact-checking the science of reading: Opening up conversations. Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- Tracey, D. H., & Morrow, L. M. (2024). Lenses on reading: An introduction to theories and models (4th ed.). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y., Kuo, L.-J., Chen, L., Lin, J.-A., & Shen, H. (2025). Vocabulary instruction for English learners: A systematic review connecting theories, research, and practices. Education Sciences, 15(3), 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chaseley, T.; Chen, Q. Connecting Beliefs and Practice: Graduate Students’ Approaches to Theoretical Integration and Equitable Literacy Teaching. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101411

Chaseley T, Chen Q. Connecting Beliefs and Practice: Graduate Students’ Approaches to Theoretical Integration and Equitable Literacy Teaching. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101411

Chicago/Turabian StyleChaseley, Tina, and Qian Chen. 2025. "Connecting Beliefs and Practice: Graduate Students’ Approaches to Theoretical Integration and Equitable Literacy Teaching" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101411

APA StyleChaseley, T., & Chen, Q. (2025). Connecting Beliefs and Practice: Graduate Students’ Approaches to Theoretical Integration and Equitable Literacy Teaching. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101411