Unveiling Students’ Voices: An Exploratory Study of Portuguese Students’ Feelings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Well-Being and Self-Determination Theory

2.2. Well-Being and Classroom Climate

2.2.1. Socio-Emotional Support

2.2.2. Support for Learning

2.2.3. Classroom Organization and Management

2.3. Current Study and Hypothesis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection, Instrument, and Participants

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Mapping Students’ Feelings

4.2. H1 to H3 Hypotheses Testing

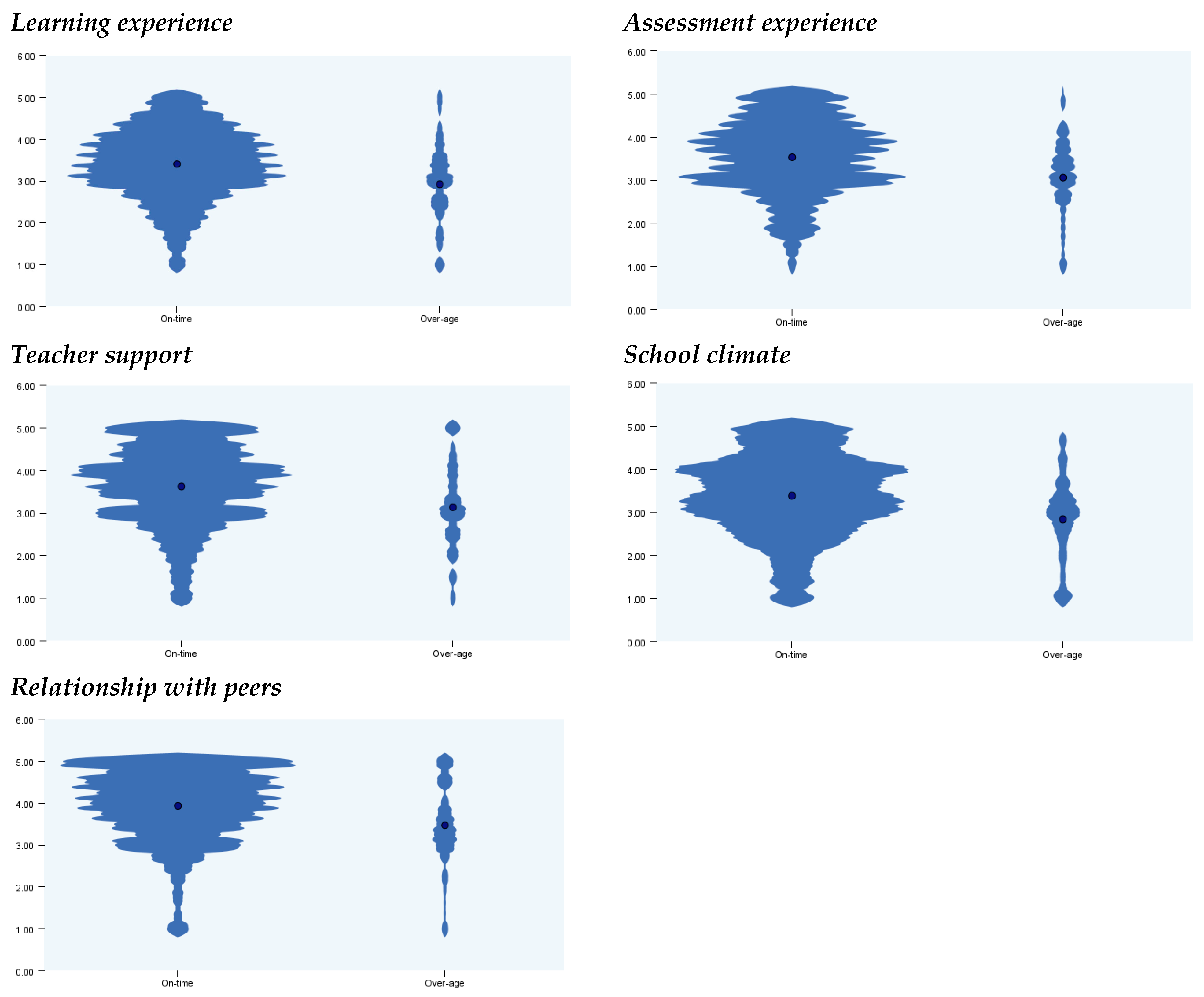

4.2.1. Effect of Age by Reference to the Grade Attended

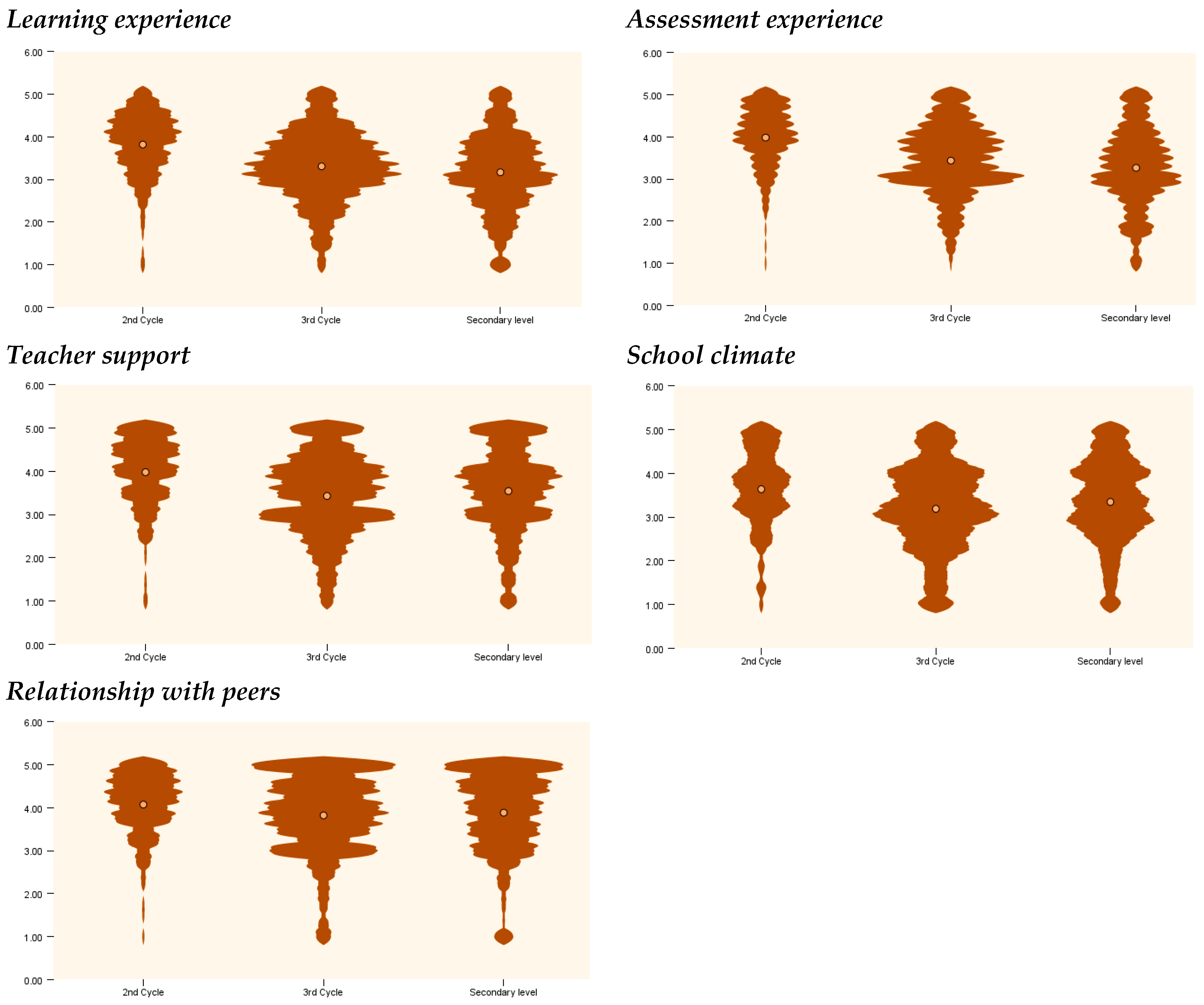

4.2.2. Effect of the Schooling Level

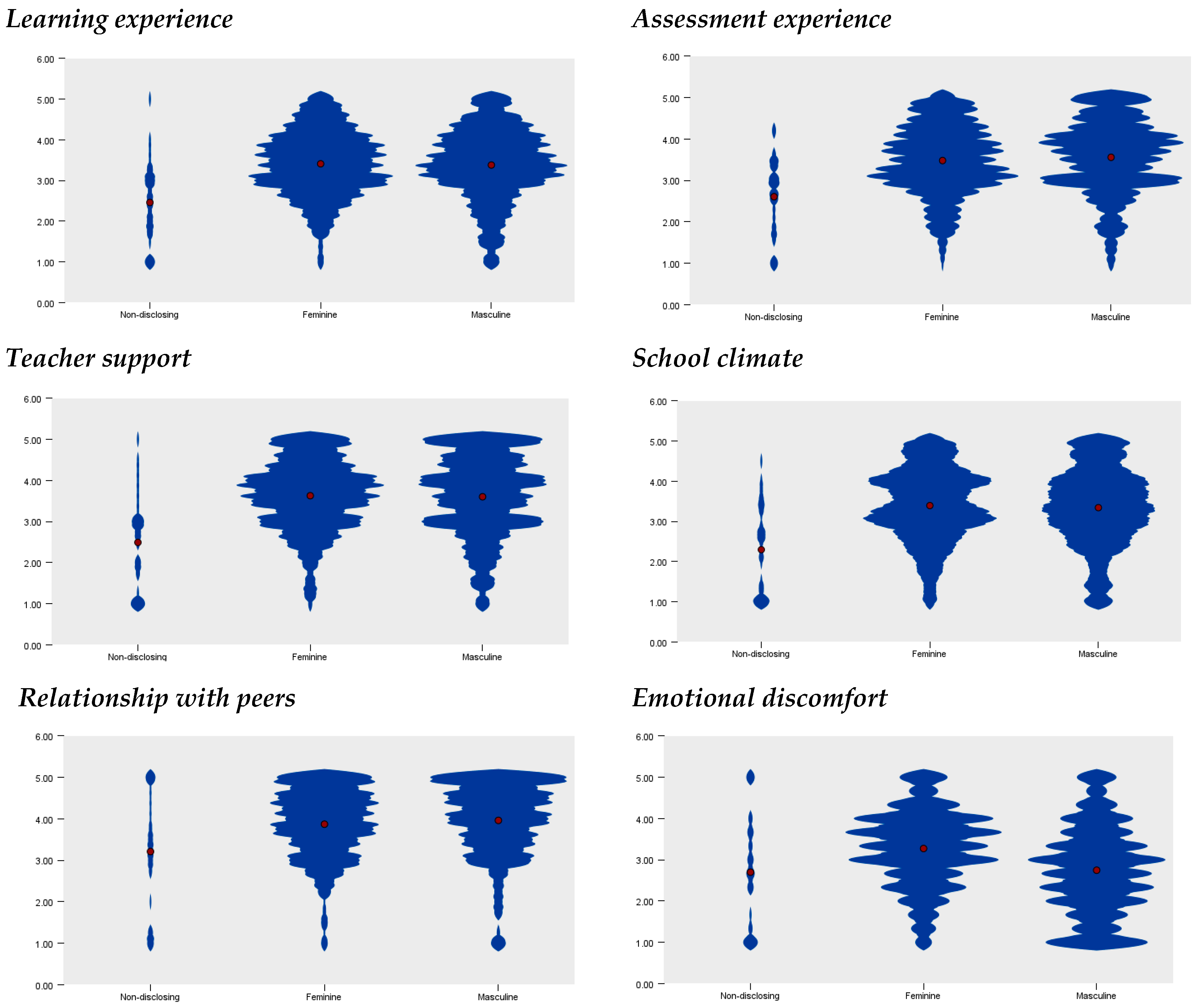

4.2.3. Effect of Gender

4.3. H4 Hypothesis Testing

4.4. Study’s Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SL | Secondary Level |

| LE | Learning experience |

| AE | Assessment experience |

| TS | Teacher support |

| SC | School climate |

| RwP | Relationship with peers |

| ED | Emotional discomfort |

| AGS | Age-for-grade status |

| G | Grade |

| VIF | Variation Inflation Factor |

References

- Abdullah, M. I., Inayati, D., & Karyawati, N. N. (2022). Nearpod use as a learning platform to improve student learning motivation in an elementary school. Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn), 16(1), 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, L. (2021). António Nóvoa: Aprendizagem precisa considerar o sentir. Available online: https://revistaeducacao.com.br/2021/06/25/Antonio-Novoa-Aprendizagem-Sentir/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Arbuthnot, K. (2017). Global perspectives on educational testing: Examining fairness, high-stakes and policy reform. Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Blanca, M. J., Alarcón, R., Arnau, J., Bono, R., & Bendayan, R. (2017). Non-normal data: Is ANOVA still a valid option? Psicothema, 29(4), 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandmo, C., & Gamlem, S. M. (2025). Students’ perceptions and outcome of teacher feedback: A systematic review. In Frontiers in education (Vol. 10). Frontiers Media SA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidenstein, G. (2007). The meaning of boredom in school lessons. Participant observation in the seventh and eighth form. Ethnography and Education, 2(1), 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefai, C., Simões, C., & Carvita, S. (2021). A systemic, whole-school approach to mental health and well-being in schools in the EU. NESET. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, K., Clark, D. M., & Leigh, E. (2021). Prospective associations between peer functioning and social anxiety in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, T. (2023). Do scores ‘define’ us? Adolescents’ experiences of wellbeing as ‘welldoing’ at school in England. Review of Education, 11(1), e3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corominas, M., González-Carrasco, M., & Casas, F. (2022). Children’s school subjective Well-Being: The importance of schools in perception of support received from classmates. Psicologia Educativa, 28(2), 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, A., Gül, M., & Doğanay, A. (2021). How students feel at school: Experiences and reasons. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies, 8(2), 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, A., Schirripa Spagnolo, F., & Salvati, N. (2022). Studying the relationship between anxiety and school achievement: Evidence from PISA data. Statistical Methods and Applications, 31(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damásio, A. (2020). Sentir & Saber—A caminho da consciência, temas e debates (1st ed.). Círculo de leitores. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T., & Bellmore, A. (2023). Connecting Feelings of school belonging to high school students’ friendship quality profiles. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 40(8), 2488–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, F. B., Cerqueira, A., Gaspar, S., Gaspar, T., Moreno, C., & de Matos, M. G. (2023). Quality of life and Well-Being of adolescents in Portuguese schools. Child Indicators Research, 16(4), 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, E., Elhawary, D., & Mahgoub, M. (2018). ‘The teacher who helps children learn best’: Affect and authority in the traditional primary classroom. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 26(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, S. (2009). Teacher and classmate influences on scholastic motivation, self-esteem, and level of voice in adolescents. In Social motivation (pp. 11–42). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoferichter, F., Kulakow, S., & Raufelder, D. (2022). How teacher and classmate support relate to students’ stress and academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 992497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, N., Palmer, T. A., Koh, G. A., Lai, M. Y., Dong, Y., Loch, S., & Yu, K. (2025). Understanding student emotions when completing assessment: Technological, teacher and student perspectives. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 48(2), 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E. S., Gilman, R., Reschly, A., & Hall, R. (2009). Positive school, in handbook of positive psychology (S. J. Lopez, Ed.). Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, A., & El Zataari, W. (2020). The teacher–student relationship and adolescents’ sense of school belonging. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2017). An introduction to statistical learning. In R. Koenker, V. Chernozhukov, X. He, & L. Peng (Eds.), Handbook of quantile regression (8th ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A. L., & Zhang, L. J. (2021). University teachers’ teaching style and their students’ agentic engagement in EFL learning in China: A self-determination theory and achievement goal theory integrated perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 704269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandemir, M. (2013). A model explaining test anxiety: Perfectionist personality traits and performance achievement goals. International Journal of Academic Research, 5(5), 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapp, T., Klapp, A., & Gustafsson, J. E. (2024). Relations between students’ well-being and academic achievement: Evidence from Swedish compulsory schools. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39(1), 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, F. (2016). Motivation to learn and teacher-student relationship. Journal of International Education and Leadership, 6(2), 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., & Xue, E. (2023). Dynamic interaction between student learning behaviour and learning environment: Meta-analysis of student engagement and its influencing factors. Behavioral Sciences, 13(1), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoCasale-Crouch, J., Jamil, F., Pianta, R. C., Rudasill, K. M., & DeCoster, J. (2018). Observed quality and consistency of fifth graders’ teacher–student interactions: Associations with feelings, engagement, and performance in school. SAGE Open, 8(3), 215824401879477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looker, B., Kington, A., & Vickers, J. (2023). Close and conflictual: How pupil–teacher relationships can contribute to the alienation of pupils from secondary school. Education Sciences, 13(10), 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, T., Diehr, P., Emerson, S., & Chen, L. (2002). The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Annual Review of Public Health, 23, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykken, D., & Tellegen, A. (1996). Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychological Science, 7(3), 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, J. (2024). Gender differences in school effects on adolescent life satisfaction: Exploring cross-national variation. Child and Youth Care Forum, 53(2), 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín de Hijas-Larrea, L., de Anda-Martín, I. O., & Díaz-Iso, A. (2025). Teaching with ears wide open: The value of empathic listening. Education Sciences, 15(3), 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDiarmid, G. W. (2023). What really matters: Prioritizing youth mental health in an age of growing uncertainty. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 24(1), 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, R. W., Seehuus, M., & Peisch, V. (2020). Emotional intelligence, belongingness, and mental health in college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, V., Carvalho, C., & Santos, N. N. (2021). Creating a Supportive classroom environment through effective feedback: Effects on students’ school identification and behavioral engagement. Frontiers in Education, 6, 661736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, M., Yamazaki, C., Teshirogi, H., Kubo, H., Ogawa, Y., Kameo, S., Inoue, K., & Koyama, H. (2022). How worries about interpersonal relationships, academic performance, family support, and classmate social capital influence suicidal ideation among adolescents in Japan. Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine, 256(1), 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2025, July 25). OECD Statistics blog. Available online: https://oecdstatistics.blog/2025/04/08/from-Data-to-Action-Enhancing-Childrens-Lives-through-Better-Insights/?Utm_source=chatgpt.Com (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Opre, D., Pintea, S., Opre, A., & Bertea, M. (2018). Measuring adolescents’ subjective well-being in an educational context: Development and validation of a multidimensional instrument. Journal of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies, 18(2), 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Op’t Eynde, P., & Turner, J. E. (2006). Focusing on the complexity of emotion issues in academic learning: A dynamical component systems approach. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovalle, H., Nussbaum, M., Claro, S., Espinosa, P., & Alvares, D. (2024). Happiness at school and its relationship with academic achievement. Education Sciences, 14(12), 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, B. C., Stockbridge, S., Roosa, H. V., & Edelson, J. S. (2019). Self-silencing in school: Failures in student autonomy and teacher-student relatedness. Social Psychology of Education, 22(4), 943–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrenoud, P. (1996). Métier d’élève et Sens du Travail Scolaire. ESF. [Google Scholar]

- Pestana, M. H., & Gageiro, J. N. (2014). Análise de Dados para Ciências Sociais: A complementariedade do SPSS (6th ed.). Edições Silabo. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro-Silva, E., Amorim, C., Aparicio-Herguedas, J. L., & Batista, P. (2022). Trends of active learning in higher education and students’ well-being: A literature review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 844236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, C., & Mishra, P. (2018). Learning environments that support student creativity: Developing the SCALE. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 27, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Weinstein, N. (2009). Undermining quality teaching and learning: A self-determination theory perspective on high-stakes testing. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2), 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkamp, K., van der Kleij, F. M., Heitink, M. C., Kippers, W. B., & Veldkamp, B. P. (2020). Formative assessment: A systematic review of critical teacher prerequisites for classroom practice. International Journal of Educational Research, 103, 101602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, L., Alves, J. M., & Pinheiro, G. (2025). Development and validation of a scale to measure students’ feelings about school: An exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis approach. American Journal of Education and Learning, 10(2), 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y., & Kang, S. (2022). The association between peer relationship and learning engagement among adolescents: The chain mediating roles of self-efficacy and academic resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 938756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sointu, E. T., Savolainen, H., Lappalainen, K., & Lambert, M. C. (2017). Longitudinal associations of student–teacher relationships and behavioural and emotional strengths on academic achievement. Educational Psychology, 37(4), 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. (2021). The effect of teacher caring behavior and teacher praise on students’ engagement in EFL classrooms. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 746871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S. H., Cassady, J. C., Wong, J. K. C., Khng, K. H., & Leong, W. S. (2025). A systematic review of test anxiety identification and leveling in children and adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 62(8), 2373–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlektsi, E., Kreppner, J., Mahon, M., Worsfold, S., & Kennedy, C. R. (2020). Peer relationship experiences of deaf and hard-of-hearing adolescents. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 25(2), 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M., Te, L., Degol, J., Amemiya, J., Parr, A., & Guo, J. (2020). Classroom climate and children’s academic and psychological well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Developmental Review, 57, 100912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Wang, H., Wang, S., Wind, S. A., & Gill, C. (2024). A systematic review and meta-analysis of self-determination-theory-based interventions in the education context. Learning and Motivation, 87, 102015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, M. W. (2018). Exploratory factor analysis: A guide to best practice. Journal of Black Psychology, 44(3), 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S., Schneider, M., Wornell, C., & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. (2018). Students’ perceptions of school safety: It is not just about being bullied. Journal of School Nursing, 34(4), 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K., & Hattie, J. (2020). The Power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Yang, Y., Ge, J., Liang, X., & An, Z. (2023). Stimulating creativity in the classroom: Examining the impact of sense of place on students’ creativity and the mediating effect of classmate relationships. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, F. (2022). Fostering students’ well-being: The mediating role of teacher interpersonal behavior and student-teacher relationships. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 796728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Minimum–Maximum | Mean | Standard Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 9–20 | 14.18 | 2.249 | 0.056 | −0.756 |

| Age-for-grade-status 1 | 0–4 | 0.12 | 0.402 | 4.188 | 21.220 |

| Frequencies | No | % | |||

| Direct school path | 920 | 90.9% | |||

| Gender | Non-disclosing | 31 | 3.1% | ||

| Female | 487 | 48.1% | |||

| Male | 494 | 48.8% | |||

| School year | 5th grade | 81 | 8.0% | ||

| 6th grade | 127 | 12.5% | |||

| 7th grade | 136 | 13.4% | |||

| 8th grade | 143 | 14.1% | |||

| 9th grade | 181 | 17.9% | |||

| 10th grade | 147 | 14.5% | |||

| 11th grade | 130 | 12.8% | |||

| 12th grade | 67 | 6.6% | |||

| Mean | Standard Deviation | T | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On-Time | Over-Age | On-Time | Over-Age | |||

| I. Feelings about the learning experience | 3.41 | 2.92 | 0.848 | 0.946 | 5.184 a | <0.001 |

| II. Feelings about the assessment experience | 3.53 | 3.06 | 0.872 | 0.893 | 4.976 a | <0.001 |

| III. Feelings about the teacher support | 3.63 | 3.14 | 0.933 | 1.036 | 4.750 a | <0.001 |

| IV. Feelings about the school climate | 3.38 | 2.84 | 0.956 | 0.977 | 5.174 a | <0.001 |

| V. Feelings about relationship with peers | 3.94 | 3.47 | 0.863 | 1.034 | 4.186 b | <0.001 |

| VI. Feelings about emotional discomfort | 3.01 | 2.93 | 1.034 | 1.071 | 0.719 a | 0.236 |

| Item | Mean | Standard Deviation | Alfa Cronbach If Item Excluded | Mean | Standard Deviation | Range of Inter-Item Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor I: Feelings about the learning experience | |||||||

| It1 | 3.60 | 1.027 | 0.789 | 3.37 | 0.869 | 0.442–0.636 | 0.823 |

| It2 | 3.22 | 1.025 | 0.796 | ||||

| It3 | 3.30 | 1.175 | 0.794 | ||||

| It4 | 3.34 | 1.064 | 0.728 | ||||

| Factor 2: Feelings about the assessment experience | |||||||

| It5 | 3.83 | 1.020 | 0.850 | 3.49 | 0.884 | 0.448–0.644 | 0.859 |

| It6 | 3.36 | 1.175 | 0.822 | ||||

| It7 | 3.51 | 1.095 | 0.813 | ||||

| It8 | 3.42 | 1.103 | 0.839 | ||||

| It9 | 3.32 | 1.132 | 0.822 | ||||

| Factor 3: Feelings about teacher support | |||||||

| It10 | 3.38 | 1.131 | 0.843 | 3.58 | 0.955 | 0.580–0.715 | 0.879 |

| It11 | 3.51 | 1.083 | 0.822 | ||||

| It12 | 3.80 | 1.075 | 0.842 | ||||

| It13 | 3.63 | 1.159 | 0.871 | ||||

| Factor 4: Feelings about the school climate | |||||||

| It14 | 3.18 | 1.286 | 0.893 | 3.33 | 0.970 | 0.502–0.697 | 0.897 |

| It15 | 3.46 | 1.208 | 0.872 | ||||

| It16 | 3.06 | 1.181 | 0.871 | ||||

| It17 | 3.25 | 1.131 | 0.870 | ||||

| It18 | 3.62 | 1.173 | 0.875 | ||||

| It19 | 3.44 | 1.178 | 0.891 | ||||

| Factor 5: V. Feelings about the relationship with peers | |||||||

| It20 | 4.25 | 1.035 | 0.773 | 3.89 | 0.889 | 0.350–0.709 | 0.823 |

| It21 | 4.03 | 1.078 | 0.730 | ||||

| It22 | 3.82 | 1.085 | 0.742 | ||||

| It23 | 3.48 | 1.198 | 0.855 | ||||

| Factor 6: Feelings about emotional discomfort | |||||||

| It24 | 2.94 | 1.396 | 0.386 | 3.00 | 1.037 | 0.239–0.487 | 0.632 |

| It25 | 2.43 | 1.360 | 0.655 | ||||

| It26 | 3.63 | 1.344 | 0.531 | ||||

| ANOVA | Post Hoc (Mean Difference) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | F | p | Partial Eta Square | Observed Power | 3rd Cycle | SL | |

| I. Feelings about the learning experience (b) | |||||||

| 2nd Cycle | 3.82 | 41.336 | <0.001 | 0.076 | 1.000 | 0.5116 * | 0.6511 * |

| 3rd Cycle | 3.31 | 0.1395 ns. | |||||

| SL | 3.17 | ||||||

| II. Feelings about assessment (b) | |||||||

| 2nd Cycle | 3.98 | 48.509 | <0.001 | 0.088 | 1.000 | 0.5463 * | 0.7185 * |

| 3rd Cycle | 3.44 | 0.1723 *** | |||||

| SL | |||||||

| III. Feelings about teacher support (b) | |||||||

| 2nd Cycle | 3.98 | 25.480 | <0.001 | 0.048 | 1.000 | 0.5502 * | 0.4367 * |

| 3rd Cycle | 3.43 | −0.1135 ns. | |||||

| SL | |||||||

| IV. School climate (a) | |||||||

| 2nd Cycle | 3.64 | 15.825 | <0.001 | 0.030 | 1.000 | 0.4486 * | 0.2914 ** |

| 3rd Cycle | 3.19 | −0.1573 ns. | |||||

| SL | 3.35 | ||||||

| V. Relationship with peers (b) | |||||||

| 2nd Cycle | 4.07 | 5.827 | 0.003 | 0.011 | 0.872 | 0.2516 * | 0.1896 *** |

| 3rd Cycle | 3.82 | −0.0620 ns. | |||||

| SL | 3.88 | ||||||

| VI. Emotional discomfort (b) | |||||||

| 2nd Cycle | 3.05 | 1.469 | 0.231 | 0.003 | 0.315 | 0.1175 ns. | 0.0089 ns. |

| 3rd Cycle | 2.94 | −0.1086 ns. | |||||

| SL | 3.05 | ||||||

| ANOVA | Post Hoc (Mean Difference) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | F | p | Partial Eta Square | Observed Power | 3rd Cycle | SL | |

| I. Feelings about the learning experience (b) | |||||||

| ND | 2.46 | 18.147 | <0.001 | 0.035 | 1.000 | −0.9500 * | −0.9199 * |

| Female | 3.41 | 0.0301 ns. | |||||

| Male | 3.38 | ||||||

| II. Feelings about assessment (b) | |||||||

| ND | 2.61 | 17.514 | <0.001 | 0.034 | 1.000 | −0.8732 * | −0.9514 * |

| Female | 3.48 | −0.0782 ns. | |||||

| Male | 3.56 | ||||||

| III. Feelings about teacher support (b) | |||||||

| ND | 2.49 | 21.847 | <0.001 | 0.042 | 1.000 | −1.1364 * | −1.1108 * |

| Female | 3.63 | 0.0256 ns. | |||||

| Male | 3.60 | ||||||

| IV. School climate (a) | |||||||

| ND | 2.30 | 19.392 | <0.001 | 0.037 | 1.000 | −1.0979 * | −1.0464 * |

| Female | 3.39 | 0.0515 ns. | |||||

| Male | 3.34 | ||||||

| V. Relationship with peers (b) | |||||||

| ND | 3.21 | 10.995 | <0.001 | 0.021 | 0.991 | −0.6604 ** | −0.7519 ** |

| Female | 3.87 | −0.0914 ns. | |||||

| Male | 3.96 | ||||||

| VI. Emotional discomfort (b) | |||||||

| ND | 2.70 | 35.116 | <0.001 | 0.065 | 1.000 | −0.5735 ns. | −0.0474 ns. |

| Female | 3.27 | 0.5261 * | |||||

| Male | 2.74 | ||||||

| ANOVA | Coefficient | Collinearity | Partial Correlation | Effect * | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | r2 | F | Sig. | Β | T | Sig. | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| Dependent variable: Feeling well during classes | |||||||||||

| 0.737 | 0.543 | 149.155 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Constant | 0.914 | 5.267 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Learning experience (LE) | 0.336 | 10.311 | <0.001 | 0.429 | 2.330 | 0.310 | 4.84% | ||||

| Assessment experience (AE) | 0.140 | 3.947 | <0.001 | 0.362 | 2.762 | 0.124 | 0.71% | ||||

| Teacher support (TS) | 0.114 | 3.331 | <0.001 | 0.392 | 2.551 | 0.105 | 0.50% | ||||

| School climate (SC) | 0.176 | 5.329 | <0.001 | 0.419 | 2.384 | 0.166 | 1.30% | ||||

| Relationship with peers (RwP) | 0.068 | 2.434 | 0.015 | 0.580 | 1.697 | 0.077 | 0.27% | ||||

| Emotional discomfort (ED) | −0.063 | −2.947 | 0.003 | 0.987 | 1.014 | −0.093 | 0.34% | ||||

| Age-for-grade status AGS) | −0.058 | −2.662 | 0.008 | 0.955 | 1.047 | −0.084 | 0.33% | ||||

| Grade (G) | −0.066 | −2.892 | 0.004 | 0.865 | 1.156 | −0.091 | 0.38% | ||||

| Independent variables interaction | 45.23% | ||||||||||

| Dependent variable: Feelings about the learning experience | |||||||||||

| 0.755 | 0.571 | 222.702 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Constant | 0.912 | 6.518 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Assessment experience (AE) | 0.364 | 11.257 | <0.001 | 0.408 | 2.453 | 0.335 | 5.429% | ||||

| Teacher support (TS) | 0.178 | 5.464 | <0.001 | 0.404 | 2.478 | 0.170 | 1.28% | ||||

| School climate (SC) | 0.236 | 7.630 | <0.001 | 0.446 | 2.244 | 0.234 | 2.50% | ||||

| Relationship with peers (RwP) | 0.050 | 1.847 | 0.065 | 0.593 | 1.683 | 0.058 | 0.14% | ||||

| Emotional discomfort (ED) | 0.050 | 2.395 | 0.017 | 0.992 | 1.008 | 0.075 | 0.25% | ||||

| Grade (G) | −0.108 | −4.920 | <0.001 | 0.901 | 1.110 | −0.103 | 1.06% | ||||

| Independent variables interaction | 46.44% | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serra, L.; Alves, J.M.; Pinheiro, G. Unveiling Students’ Voices: An Exploratory Study of Portuguese Students’ Feelings. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1403. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101403

Serra L, Alves JM, Pinheiro G. Unveiling Students’ Voices: An Exploratory Study of Portuguese Students’ Feelings. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1403. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101403

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerra, Lídia, José Matias Alves, and Generosa Pinheiro. 2025. "Unveiling Students’ Voices: An Exploratory Study of Portuguese Students’ Feelings" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1403. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101403

APA StyleSerra, L., Alves, J. M., & Pinheiro, G. (2025). Unveiling Students’ Voices: An Exploratory Study of Portuguese Students’ Feelings. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1403. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101403