Effects of AI-Assisted Feedback via Generative Chat on Academic Writing in Higher Education Students: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

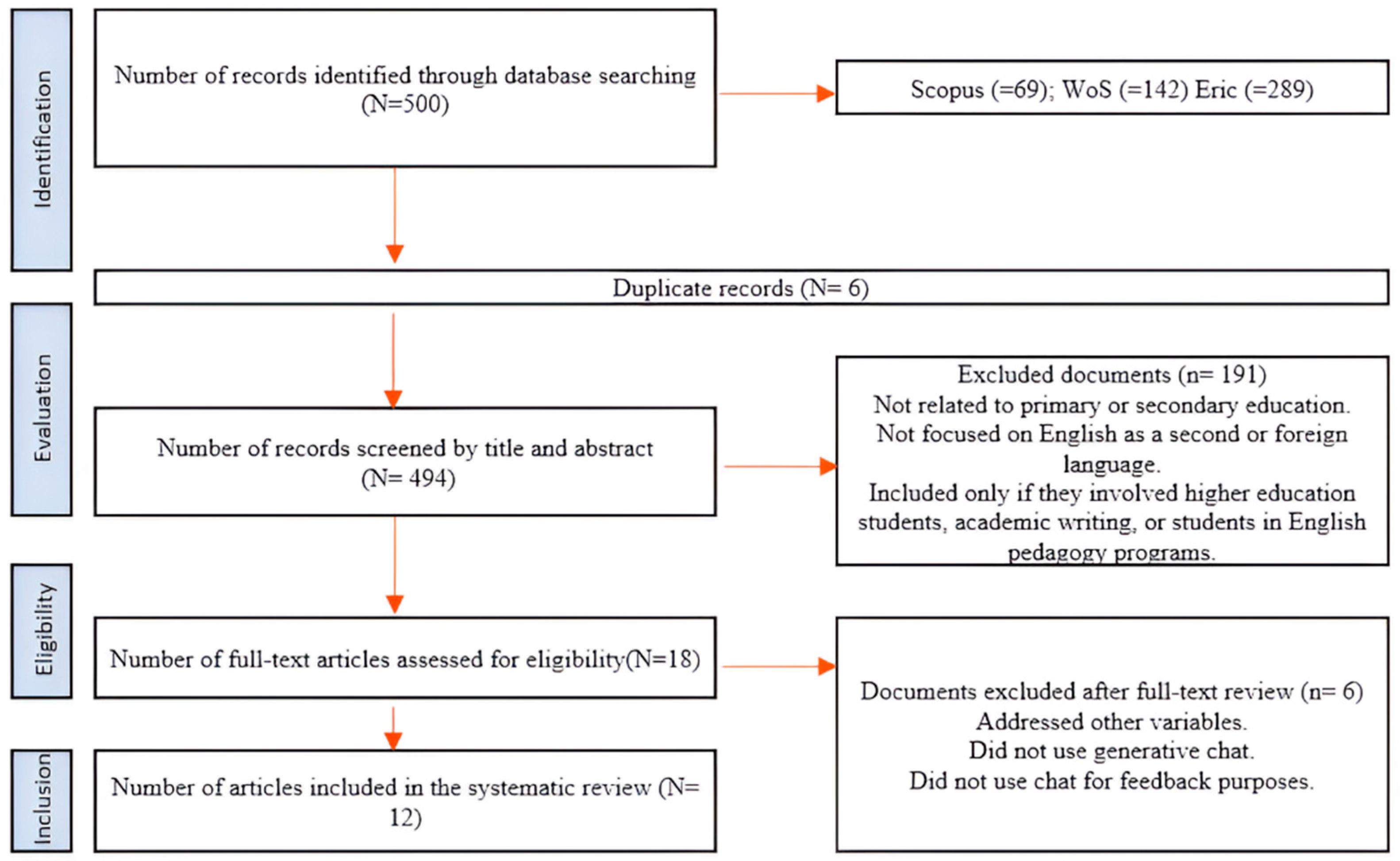

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Studies had to be published between 2021 and 2025 (to select the latest research findings on the use of generative chat feedback and to know the state of the art).

- Articles written in any language were accepted, with English being the most common.

- Empirical research (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods) that explicitly incorporated the implementation of generative chat feedback as a main component in the context of academic writing assessment.

- Only articles from scientific journals were included.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Publications that were systematic reviews of the literature, conference proceedings and presentations, editorials, or conceptual and theoretical articles, essays and book chapters were excluded.

- Some of the studies, though appearing in the search, were excluded as they did not focus on feedback through the use of generative chat (for example, we excluded studies on “menu-based chat,” “rule-based chat,” “voice chat,” “non-generative AI chat,” platform-based chat, and “hybrid chatbots”).

2.3. Selection and Coding

3. Results

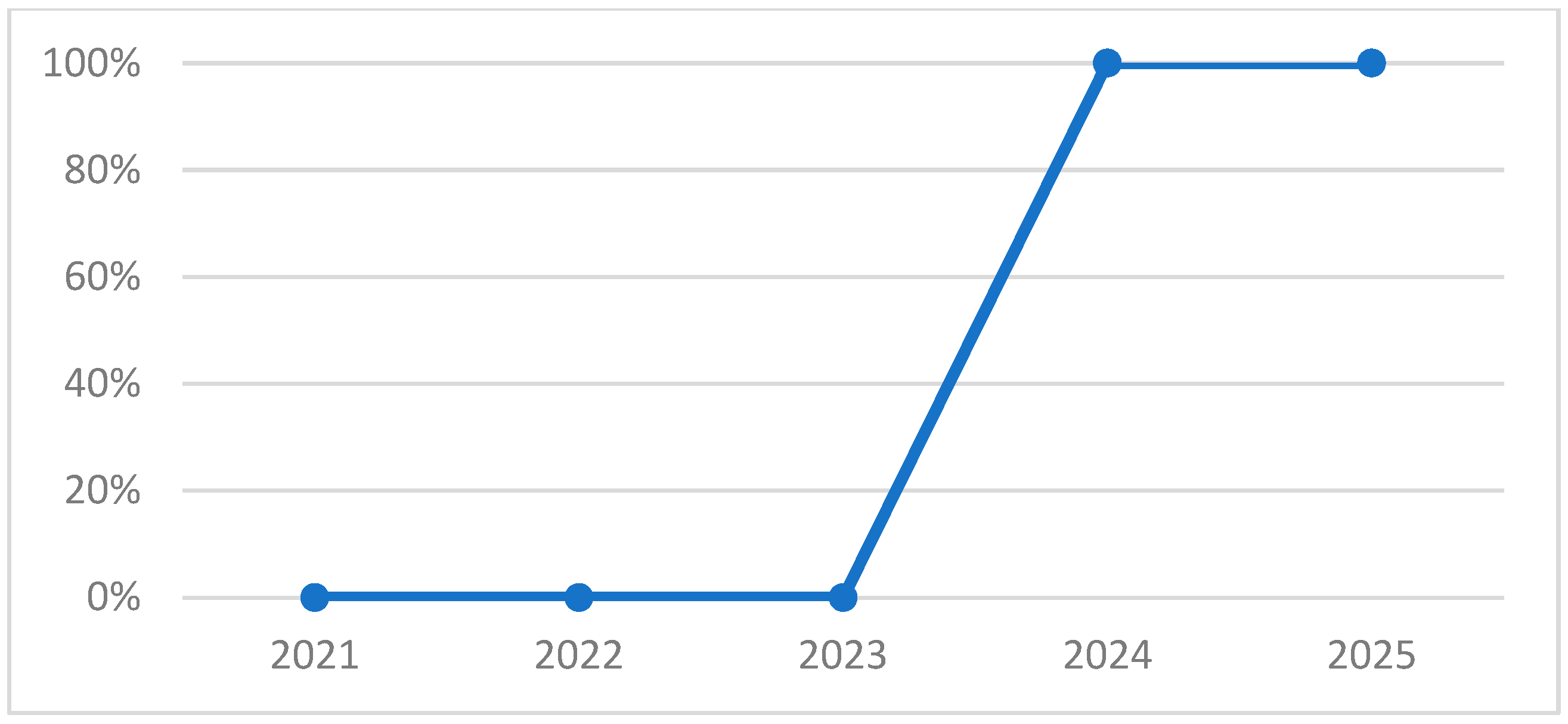

3.1. Years of Publication

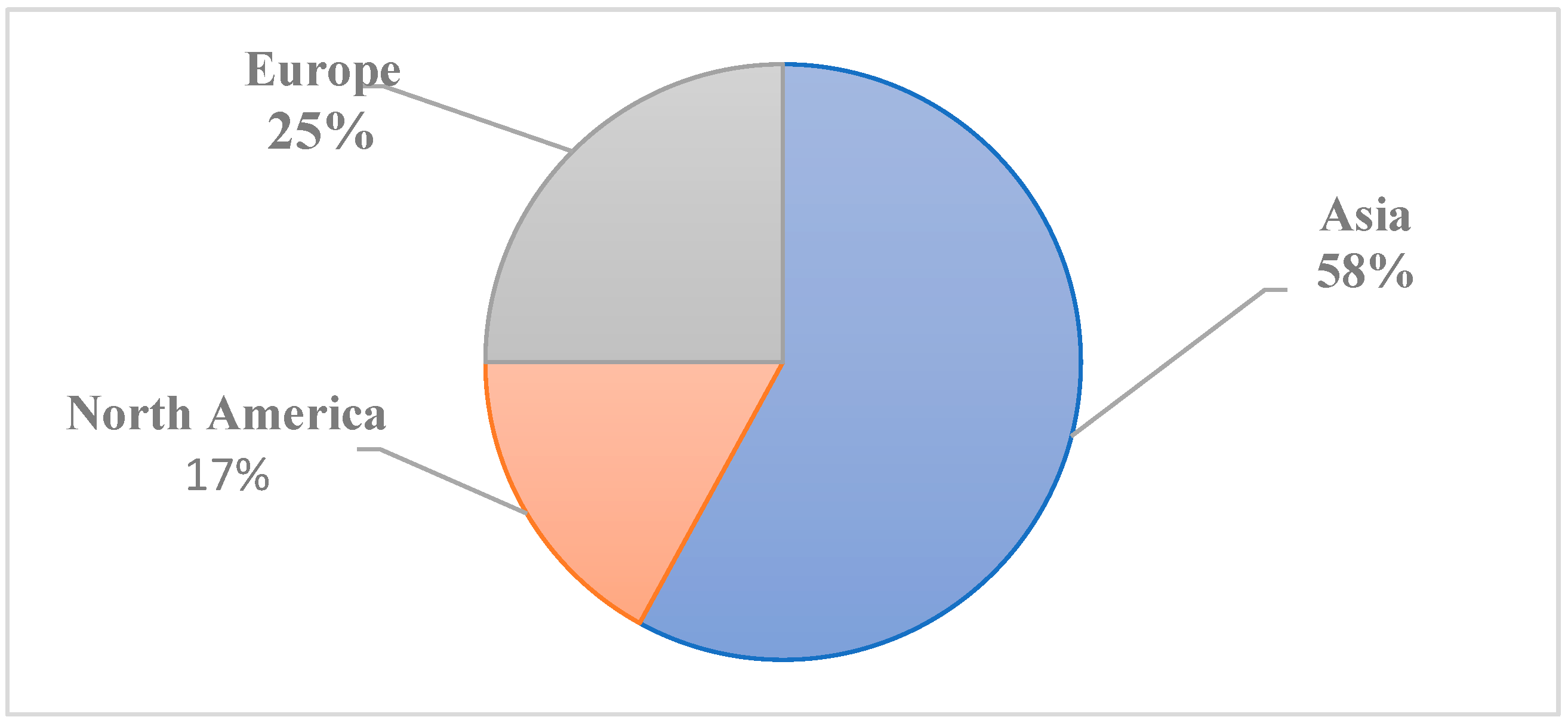

3.2. Geographical Locations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, A., & Pollitt, A. (2010). The support model for interactive assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 17(2), 133–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y. A., & Sharo, A. (2023). On the education effect of ChatGPT: Is AI ChatGPT to dominate education career profession? In 2023 international conference on intelligent computing, communication, networking and services (ICCNS) (pp. 79–84). IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amin, M., Ali, M. S., Salam, A., Khan, A., Ali, A., Ullah, A., Alam, N., & Chowdhury, S. K. (2024). History of generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) chatbots: Past, present, and future development. arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albadarin, Y., Saqr, M., Pope, N., & Tukiainen, M. (2024). A systematic literature review of empirical research on ChatGPT in education. Discover Education, 3, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghannam, M. (2025). Artificial intelligence as a provider of feedback on EFL student compositions. World Journal of English Language, 15(2), 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaissi, H., & McFarlane, S. I. (2023). Artificial hallucinations in ChatGPT: Implications in scientific writing. Cureus, 15(2), e35179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baidoo-anu, D., & Owusu Ansah, L. (2023). Education in the Era of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI): Understanding the Potential Benefits of ChatGPT in Promoting Teaching and Learning. Journal of AI, 7(1), 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banihashem, S. K., Taghizadeh Kerman, N., Noroozi, O., Moon, J., & Drachsler, H. (2024). Feedback sources in essay writing: Peer-generated or AI-generated feedback? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, L., & Blomstand, I. (2000). La escritura en la enseñanza secundaria. Los procesos del pensar y del escribir. Graó. [Google Scholar]

- Cassany, D. (1990). Enfoques didácticos para la enseñanza de la expresión escrita. Culture and Education, 2(6), 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassany, D. (2024). (Enseñar a) leer y escribir con inteligencias artificiales generativas: Reflexiones, oportunidades y retos. Enunciación, 29(2), 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Culham, R. (2005). 6 + 1 traits of writing: The complete guide for the primary grades. Scholastic Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Diego Olite, F. M., Morales Suárez, I. d. R., & Vidal Ledo, M. J. (2023). Chat GPT: Origen, evolución, retos e impactos en la educación. Educación Médica Superior, 37(2), e3876. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-21412023000200016&lng=es&tlng=es (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Dinh, C. T. (2025). Undergraduate English majors’ views on ChatGPT in academic writing: Perceived vocabulary and grammar improvement. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 19(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, K. E., & Mulvenon, S. W. (2009). A critical review of research on formative assessment: The limited scientific evidence of the impact of formative assessment in education. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 14(7), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkatmis, M. (2024). Chat GPT and creative writing: Experiences of master’s students in enhancing. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 11(3), 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, K. (2023). Exploring the opportunities and challenges of NLP models in higher education: Is ChatGPT a blessing or a curse? Frontiers in Education, 8, 1166682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gašević, D., Greiff, S., & Shaffer, D. (2022). Towards strengthening links between learning analytics and assessment: Challenges and potentials of a promising new bond. Computers in Human Behavior, 134, 107304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, A., Safranek, C. W., Huang, T., Socrates, V., Chi, L., Taylor, R. A., & Chartash, D. (2023). How does ChatGPT perform on the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE)? The implications of large language models for medical education and knowledge assessment. JMIR Medical Education, 9, e45312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisbert, J. P., & Bonfill, X. (2004). ¿Cómo realizar, evaluar y utilizar revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis? Gastroenterología y Hepatología, 27(3), 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, J. (2023, January 27). En solo cinco días, Chat GPT-3 consiguió un millón de usuarios. La Jornada. Available online: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/01/27/economia/014n1eco (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Herft, A. (2023). A teacher’s prompt guide to ChatGPT aligned with “what works best”. Department of Education, New South Wales, Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Ifenthaler, D., & Greiff, S. (2021). Leveraging learning analytics for assessment and feedback. In J. Liebowitz (Ed.), Online learning analytics (pp. 1–18). Auerbach Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. (2025). Interaction and dialogue: Integration and application of artificial intelligence in blended mode writing feedback. The Internet and Higher Education, 64, 100975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R. A., Jawaid, M., Khan, A. R., & Sajjad, M. (2023). ChatGPT—Reshaping medical education and clinical management. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 39(2), 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khlaif, Z. N., Mousa, A., Hattab, M. K., Itmazi, J., Hassan, A. A., Sanmugam, M., & Ayyoub, A. (2023). The potential and concerns of using AI in scientific research: ChatGPT performance evaluation. JMIR Medical Education, 9, e47049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D., Majdara, A., & Olson, W. (2024). A pilot study inquiring into the impact of ChatGPT on lab report writing in introductory engineering labs. International Journal of Technology in Education (IJTE), 7(2), 259–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letelier, L. M., Manríquez, J. J., & Rada, G. (2005). Revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis: ¿Son la mejor evidencia? Revista Médica de Chile, 133(2), 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Wang, Y., Luo, S., & Huang, C. (2024). The influence of GenAI on the effectiveness of argumentative writing in higher education: Evidence from a quasi-experimental study in China. Journal of Asian Public Policy, 18(2), 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. (2024). A systematic review of automated writing evaluation feedback: Validity, effects and students’ engagement. Language Teaching Research Quarterly, 45, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q., Yao, Y., Xiao, L., Yuan, M., Wang, J., & Zhu, X. (2024). Can ChatGPT effectively complement teacher assessment of undergraduate students’ academic writing? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(5), 616–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucana, Y. E., & Roldan, W. L. (2023). Chatbot basado en inteligencia artificial para la educación escolar. Horizontes Revista De Investigación En Ciencias De La Educación, 7(29), 1580–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manterola, C., Astudillo, P., Arias, E., Claros, N., & Grupo MINCIR (Metodología e Investigación en Cirugía). (2013). Revisiones sistemáticas de la literatura. Qué se debe saber acerca de ellas. Cirugía Española, 91(3), 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinkovich, J. (2006). La escritura como proceso. Frasis. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, A., & Gajardo, A. (2018). Pruebas de comprensión lectora y producción de textos (CL-PT): 5° a 8° básico. Ediciones UC. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. G., Urbanowicz, R. J., Martin, P. C. N., O’Connor, K., Li, R., Peng, P.-C., Bright, T. J., Tatonetti, N., Won, K. J., Gonzalez-Hernandez, G., & Moore, J. H. (2023). ChatGPT and large language models in academia: Opportunities and challenges. BioData Mining, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogavi, H., Chen, Y., & Lee, S. (2024). Generative AI and critical thinking in higher education. Journal of Learning Analytics, 11(1), 112–130. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Alonso-Fernández, S. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parodi, G. (2003). Relaciones entre la lectura y escritura: Una perspectiva cognitiva discursiva. Ediciones Universitarias de la Valparaiso. [Google Scholar]

- Rane, N. (2023). ChatGPT and similar generative artificial intelligence (AI) for smart industry: Role, challenges and opportunities for industry 4.0, industry 5.0 and society 5.0. Innovations in Business and Strategic Management, 2(1), 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, K. I., & Tselikas, N. D. (2023). ChatGPT and Open-AI models: A preliminary review. Future Internet, 15(6), 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarosa, M., Kusumawardani, M., Suyono, A., & Wijaya, M. H. (2020). Developing a social media-based chatbot for English learning. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 732(1), 012074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, C., & Ifenthaler, D. (2021). Investigating prompts for supporting students’ self-regulation—A remaining challenge for learning analytics approaches? The Internet and Higher Education, 49, 100791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodiq, S., & Rokib, M. (2024). Indonesian students’ use of Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer in essay writing practices. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE), 13(4), 2698–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solak, E. (2024). Examining writing feedback dynamics from ChatGPT AI and human educators: A comparative study. Pedagogika-Pedagogy, 96(7), 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sysoyev, P. V., Filatov, E. M., Khmarenko, N. I., & Murunov, S. S. (2024). Пpeпoдaвaтeль vs. иcкyccтвeнный интeллeкт: Cpaвнeниe кaчecтвa пpeдocтaвляeмoй пpeпoдaвaтeлeм и гeнepaтивным иcкyccтвeнным интeллeктoм oбpaтнoй cвязи пpи oцeнкe пиcьмeнныx твopчecкиx paбoт cтyдeнтoв [Teacher vs. AI: A comparison of the quality of teacher-provided and generative AI feedback in assessing students’ written creative work]. Пepcпeктивы Нayки и Обpaзoвaния [Perspectives of Science and Education], 5(71), 694–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedre, M., Kahila, J., & Vartiainen, H. (2023). Exploration on how co-designing with AI facilitates critical evaluation of ethics of AI in craft education. In E. Langran, P. Christensen, & J. Sanson (Eds.), Proceedings of the society for information technology & teacher education international conference (pp. 2289–2296). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/222124/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Tempelaar, D. T., Rienties, B., Mittelmeier, J., & Nguyen, Q. (2018). Student profiling in a dispositional learning analytics application using formative assessment. Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dis, E. A., Bollen, J., Zuidema, W., Van Rooij, R., & Bockting, C. L. (2023). ChatGPT: Five priorities for research. Nature, 614(7947), 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volante, L., DeLuca, C., & Klinger, D. A. (2023). Leveraging AI to enhance learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 105(1), 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Li, Z., & Bonk, C. (2024). Understanding self-directed learning in AI-assisted writing: A mixed methods study of postsecondary learners. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardat, Y., & Al Ali, R. (2024). How ChatGPT will shape the teaching learning landscape in future? Journal of Educational and Social Research, 14(1), 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardat, Y., Tashtoush, M. A., AlAli, R., & Jarrah, A. M. (2023). ChatGPT: A revolutionary tool for teaching and learning mathematics. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 19(7), em2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, M. E., Prasse, D., Phillips, M., Kadijevich, D. M., Angeli, C., Strijker, A., Carvalho, A. A., Andresen, B. B., Dobozy, E., & Laugesen, H. (2018). Challenges for IT-enabled formative assessment of complex 21st century skills. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 23(3), 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., & Hyland, K. (2018). Student engagement with teacher and automated feedback on L2 writing. Assessing Writing, 36, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year, Place | Methodology | Results | Aspects Improved by Generative Chat (Based on Culham, 2005) | Other Areas of Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Sodiq and Rokib (2024), Indonesia | Quantitative approach, use of Likert-scale surveys N = 303 students | Most students who used ChatGPT improved their essay writing and boosted their confidence. Students perceived ChatGPT as a valuable resource for enhancing grammar and sentence structure, fostering creativity, and developing solid ideas and arguments. | 2. Ideas: 2.1 Accuracy and variety: development of ideas. 3. VOICE OR PERSONAL STYLE: 3.1 Expressive capacity: Essay writing style, creativity, and originality. 5. FLUENCY AND COHESION: 5.1 Ideas flow naturally: Improved coherence 5.2 Use of connectors: Improved cohesion 6 WORD CHOICE: 6.2 Varied vocabulary: Expanding vocabulary 7. GRAMMATICAL CONVENTIONS: 7.1 Syntax: Sentence structure. | Self-efficacy |

| (2) Wang et al. (2024), USA | Mixed methods, using surveys and semi-structured interviews. N = 384 students. | ChatGPT was used for the idea generation. Student motivation improved as they perceived the benefits of using ChatGPT. Most participants demonstrated a strong responsibility for their own learning and stated that they engaged in critical reflection on their learning process. | 2. IDEAS: 2.1 Accuracy and variety: Depth of written expression 3. VOICE OR PERSONAL STYLE 3.1 Expressive capacity: Essay language 5. FLUENCY AND COHESION 5.1 Ideas flow naturally: improved writing 5.2 Use of connectors: Cohesion and writing structure 6. STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION: 6.1 Relevant text structure: Context, editing, and revision 7. GRAMMATICAL CONVENTIONS: 7.1 Syntax: Correcting sentence order. |

|

| (3) Sysoyev et al. (2024), Russia | Mixed methods. Using written essays, rubrics and statistical test. N = 350 students. | ChatGPT is comparable to the teacher in terms of criteria such as: content of the work, organization and structure, validation of ideas and arguments, and originality of the essay. ChatGPT outperformed the teacher in aspects such as: language use and essay originality, | 3. VOICE OR PERSONAL STYLE: 3.1 Expressive capacity: Essay language and depth of written expression. 4. WORD CHOICE: 4.1 Precise vocabulary: Word selection. 6. STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION: 6.1 Relevant text structure: Introduction, main body and conclusion 7. GRAMMATICAL CONVENTION: 7.1 Syntax: Sentence structure 7.3 Spelling: Accuracy. | - |

| (4) Li et al. (2024), China | Mixed quasi-experimental approach with interventions. Use of a rubric and statistical test (Pre/Posttest). N = 61 students. | Chat improves the quality of content and linguistic expression and has a positive impact by providing personalized feedback. It enhances motivation to write. | 3. VOICE OR PERSONAL STYLE: 3.1 Expressive capacity: Language 4. WORD CHOICE: 4.1 Precise vocabulary: Word accuracy 6. STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION: 6.1 Relevant text structure: content and academic style. 7. GRAMMATICAL CONVENTION: 7.1 Syntax: Sentence fluency 7.2 Morphosyntax: Correcting deficiencies in linguistic expression. |

|

| (5) Solak (2024), China | Phenomenological approach. Use of essays. Use of a closed-questionnaire content analysis. N = 15 students. | When providing feedback, teachers were more empathetic, guiding, and used emotional intelligence. In contrast, the chatbot provided more detailed and comprehensive feedback, promoted engagement, reflective learning, and the construction of diverse knowledge. | 5. FLUENCY AND COHESION: 5.1 Ideas flow naturally: Coherence 5.2 Use of connectors: Cohesion 6. STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION: 6.1 Relevant structure: Content improvement |

|

| (6) Lu et al. (2024), China | Mixed approach, use of academic summaries assessed with scoring scales, statistical test, and interviews N = 46 students | ChatGPT can be used to complement teacher evaluation. It fosters a deeper understanding of teacher assessments; encourages students to make judgements about the feedback they receive; and promotes independent thinking regarding revisions. | 2. IDEAS: 2.1 Accuracy and variety: New ideas that improved writing quality (p. 623) | Reflection on feedback and writing |

| (7) Banihashem et al. (2024), Netherlands | Mixed exploratory approach. Essays were used, along with context analysis and statistical test. N = 74 students. | ChatGPT provided more descriptive feedback. In contrast, the students contributed information that helped identify the core problem in the essay. | 5. FLUENCY AND COHESION: 5.1 Ideas flow naturally: Quality of writing 5.2 Use of connectors: Essay coherence. 6. STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION: 6.1 Relevant text structure: Overall essay structure. | - |

| (8) Kim et al. (2024), USA | Qualitative approach. Laboratory reports were reviewed (N = 28). Use of a rubric and focus group. N = 7 students | Implementing ChatGPT in the revision process improves the quality of engineering students’ lab reports due to a better understanding of the genre. However, using ChatGPT also led students to make false claims, incorrect lab procedures, or overly general statements. | 2. IDEAS: 2.1 Accuracy and variety: Idea generation 4. WORD CHOICE: 4.1 Precise vocabulary: Concise language 6. STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION: 6.1 Relevant text structure: Editing the report. | - |

| (9) Elkatmis (2024), Turkey | Qualitative approach. Semi-structured interviews N = 16 students | Students lacked knowledge about the pedagogical use of ChatGPT. There are both positive and negative perceptions, The positive view holds that ChatGPT improves writing skills and vocabulary, offers different perspectives, and makes the process more enjoyable. The native view argues that it may make the mind lazy, its information is unreliable, and its versatility could pose a threat to humanity, | 4. WORD CHOICE: 4.2 Varied vocabulary: Improves vocabulary 5. FLUENCY AND COHESION: 5.1 Ideas flow naturally: Speeds up my writing 6. STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION: 6.1 Relevant text structure: Improves text quality and effectiveness, and helps organize information | - |

| (10) Jiang (2025), China | Mixed quasi-experimental approach with intervention (conventional feedback, AI feedback, and combined feedback) N = 86 students | The combination of teacher and AI feedback significantly improved writing skills. The group that received hybrid feedback scored significantly higher in writing than the groups that received monomodal feedback. Combined feedback enhances interaction, encourages deeper reflection, and improves students’ writing. | 4. WORD CHOICE: 4.1 Precise vocabulary: Language appropriateness 6. STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION: 6.1 Relevant text structure: Clarity of headings depth of argumentative development 7. GRAMMATICAL CONVENTION: 7.1 Syntax: Sentence and phrase correction |

|

| (11) Alghannam (2025), Saudi Arabia | Document analysis: Essays were evaluated and content was coded N = 29 students | There are weaknesses in the use of ChatGPT for feedback. The comments were imprecise in relation to the text and mainly focused on content related to the message and emotion. | 2. IDEAS 2.1 Accuracy and variety: Clarity 3. VOICE OR PERSONAL STYLE 3.1 Expressive capacity: Integrity 6. STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION: 6.1 Relevant text structure: Organization and content 7. GRAMMATICAL CONVENTION: 7.3 Spelling: Literal and precise. | - |

| (12) Dinh (2025), Vietnam | Mixed method approach. Use of surveys, reflective journals, and semi-structured interviews. N = 31 students | Quantitative results revealed significant improvements in students’ perceptions regarding vocabulary accuracy, relevance, and depth. Qualitative analysis identified benefits such as vocabulary enrichment, improved grammatical accuracy, and increased confidence in academic writing. | 4. WORD CHOICE: 4.1 Precise vocabulary: Concise 4.2 Varied vocabulary: Vocabulary improvement 5. FLUENCY AND COHESION: 5.1 Ideas flow naturally: Clearer writing 5.2 Use of connectors: Cohesion, helps identify and eliminate redundancy 6. STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION: 6.1 Relevant text structure: Overall organization 7. GRAMMATICAL CONVENTION: 7.1 Syntax: Sentence structure 7.2 Morphosyntax: Word selection. | Self-efficacy. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Urzúa, C.A.C.; Ranjan, R.; Saavedra, E.E.M.; Badilla-Quintana, M.G.; Lepe-Martínez, N.; Philominraj, A. Effects of AI-Assisted Feedback via Generative Chat on Academic Writing in Higher Education Students: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101396

Urzúa CAC, Ranjan R, Saavedra EEM, Badilla-Quintana MG, Lepe-Martínez N, Philominraj A. Effects of AI-Assisted Feedback via Generative Chat on Academic Writing in Higher Education Students: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101396

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrzúa, Claudio Andrés Cerón, Ranjeeva Ranjan, Eleazar Eduardo Méndez Saavedra, María Graciela Badilla-Quintana, Nancy Lepe-Martínez, and Andrew Philominraj. 2025. "Effects of AI-Assisted Feedback via Generative Chat on Academic Writing in Higher Education Students: A Systematic Review of the Literature" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101396

APA StyleUrzúa, C. A. C., Ranjan, R., Saavedra, E. E. M., Badilla-Quintana, M. G., Lepe-Martínez, N., & Philominraj, A. (2025). Effects of AI-Assisted Feedback via Generative Chat on Academic Writing in Higher Education Students: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101396