Visual Multiplication Through Stick Intersections: Enhancing South African Elementary Learners’ Mathematical Understanding

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How can the stick intersection method be implemented to teach multiplication to intermediate phase learners?

- What impact does this visual approach have on learners’ comprehension and performance in multiplication tasks?

- What are learners’ perceptions of the stick intersection method compared to conventional multiplication instruction?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Visual Representations in Mathematics Education

2.2. Multiplication Concepts and Challenges

2.3. Visual Learning in the South African Context

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

- Development and refinement of the stick intersection method for teaching multiplication, progressing from single-digit to four-digit numbers.

- Implementation of the method with Grade 4 learners in a school in Capricorn District, Polokwane.

- Evaluation of the method’s effectiveness through pre- and post-tests, classroom observations, and learner interviews.

3.2. Participants and Setting

Ethical Considerations and Instrument Validation

3.3. Data Collection

- Pre- and post-tests: Learners completed assessments measuring their multiplication skills before and after exposure to the stick intersection method. Tests included single-digit and two-digits multiplication problems.

- Classroom observations: Lessons implementing the stick intersection method were observed and video-recorded for later analysis. Observations focused on learners’ engagement, question-asking behavior, and problem-solving strategies.

- Learners work samples: Examples of learners’ work using the stick intersection method were collected and analyzed.

- Semi-structured interviews: Following the implementation, interviews were conducted with a subset of learners (n = 15) to gather their perceptions of the visual method compared to conventional instruction.

- Teacher reflections: The classroom teacher documented observations and reflections throughout the implementation process.

Assessment Instruments

- Single-digit multiplication: 8 problems (e.g., 6 × 7, 9 × 4, 8 × 6, 7 × 9, 5 × 8, 9 × 6, 7 × 8, 6 × 9).

- Two-digit by single-digit: 6 problems (e.g., 23 × 4, 31 × 5, 42 × 3, 16 × 6, 27 × 2, 34 × 3).

- Single-digit by two-digit: 4 problems (e.g., 7 × 14, 5 × 26, 4 × 19, 6 × 15).

- Two-digit by two-digit: 2 problems (e.g., 12 × 13, 14 × 12).

3.4. Instructional Intervention

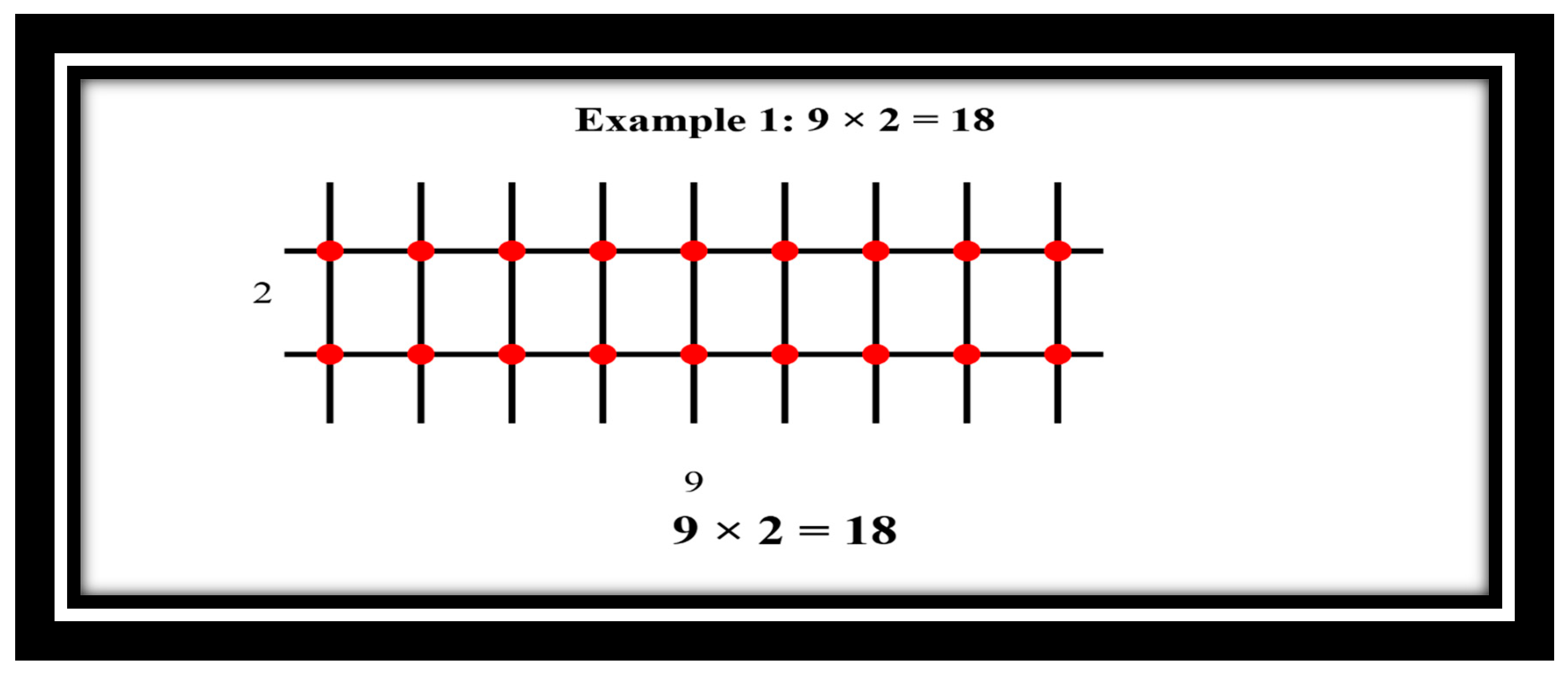

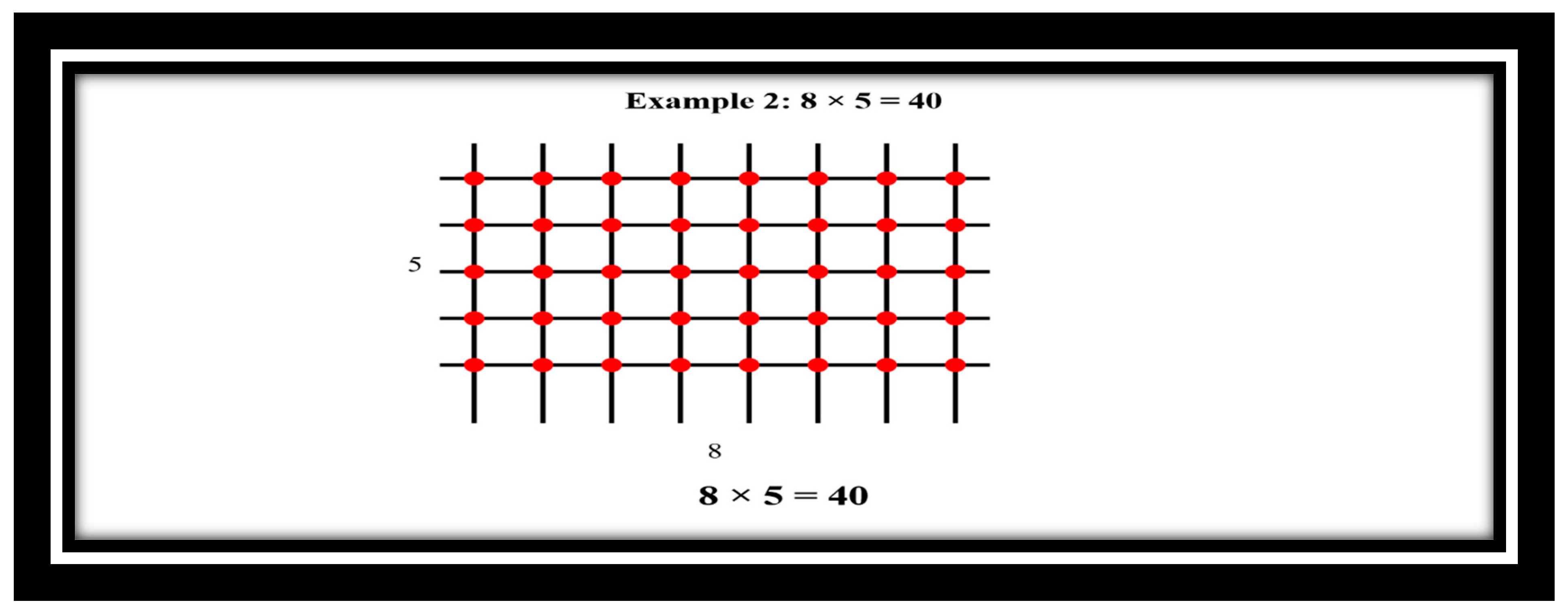

- Week 1: Single-digit multiplication (9 × 2, 8 × 5, 7 × 3, 6 × 4).

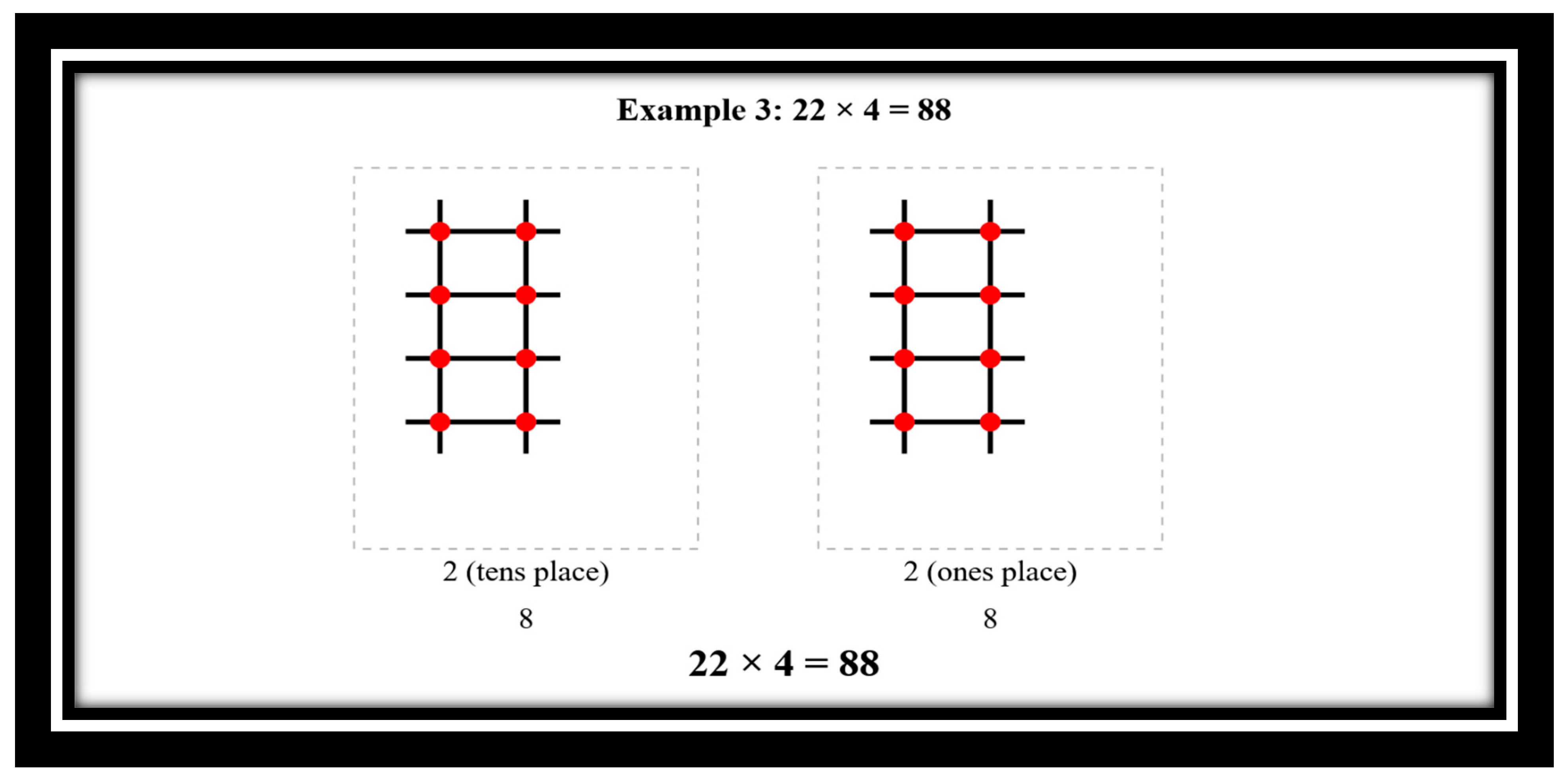

- Week 2: Two-digit by single-digit multiplication (22 × 4, 31 × 3, 42 × 2).

- Week 3: Single-digit by two-digit multiplication (6 × 13, 4 × 25, 3 × 32).

- Week 4: Two-digit by two-digit multiplication (12 × 11, 13 × 12, 14 × 11).

- Introduction phase (5 min): Present the multiplication problem on the chalkboard.

- Demonstration phase (15 min): Teacher demonstrates the stick intersection method using pre-drawn large-scale diagrams on poster paper, explaining each step while students observe.

- Guided practice (15 min): Students work in pairs, with the teacher circulating and providing support, using A4 paper and pencils to create their own stick diagrams.

- Independent application (8 min): Students individually solve 2–3 similar problems using the method.

- Discussion and reflection (2 min): Whole-class discussion of visual patterns observed and connections to mathematical concepts.

3.5. Data Analysis

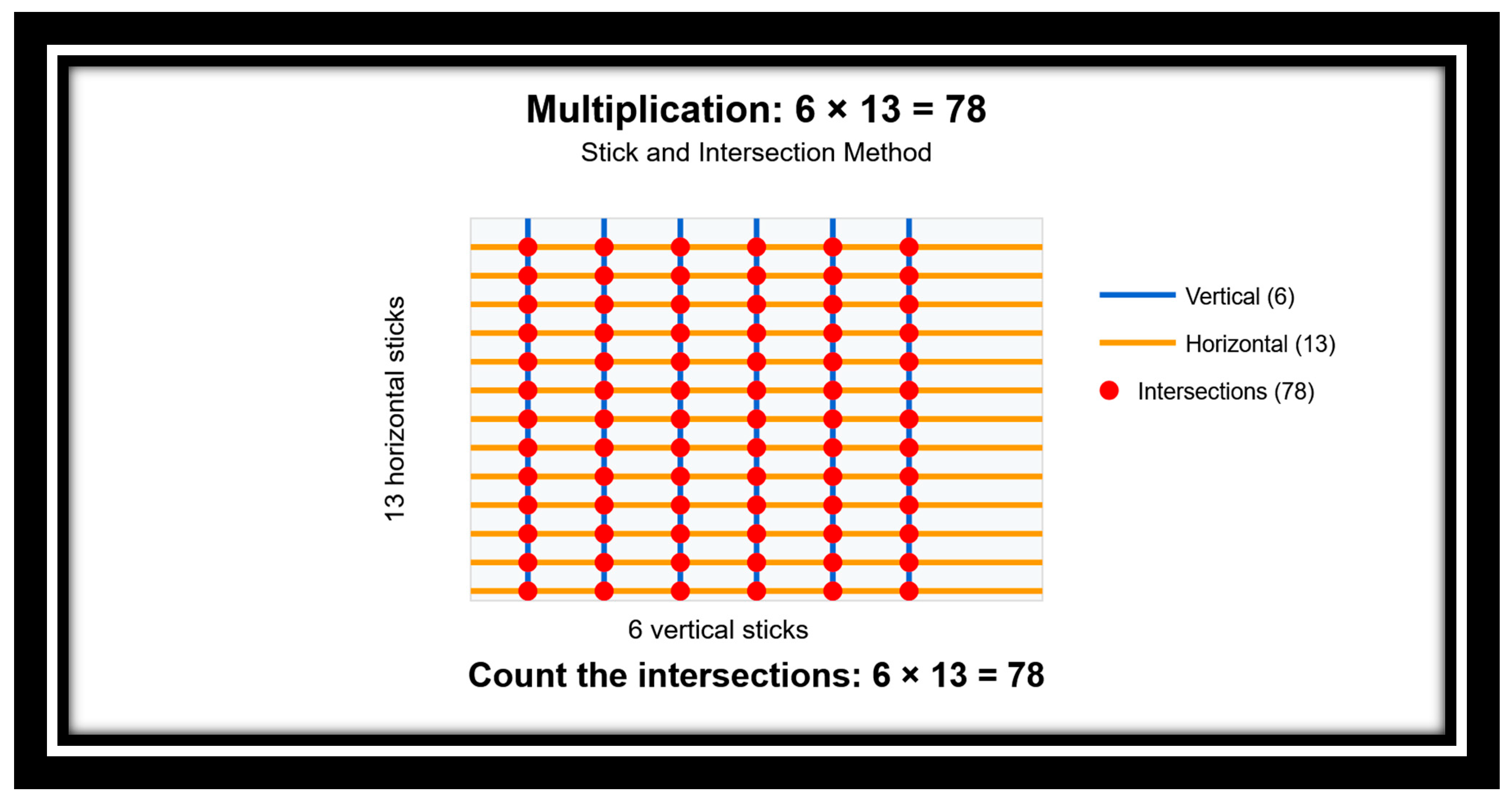

4. The Stick Intersection Method

4.1. Foundational Concept: Multiplication as Counting Intersections

4.2. Single-Digit Multiplication

4.2.1. Example 1: 9 × 2

4.2.2. Example 2: 8 × 5

4.3. Two-Digit by Single-Digit Multiplication

Example 3: 22 × 4

4.4. Single-Digit by Two-Digits Multiplication

Example 4: 6 × 13 (See Figure 4)

4.5. Two-Digit by Two-Digit Multiplication

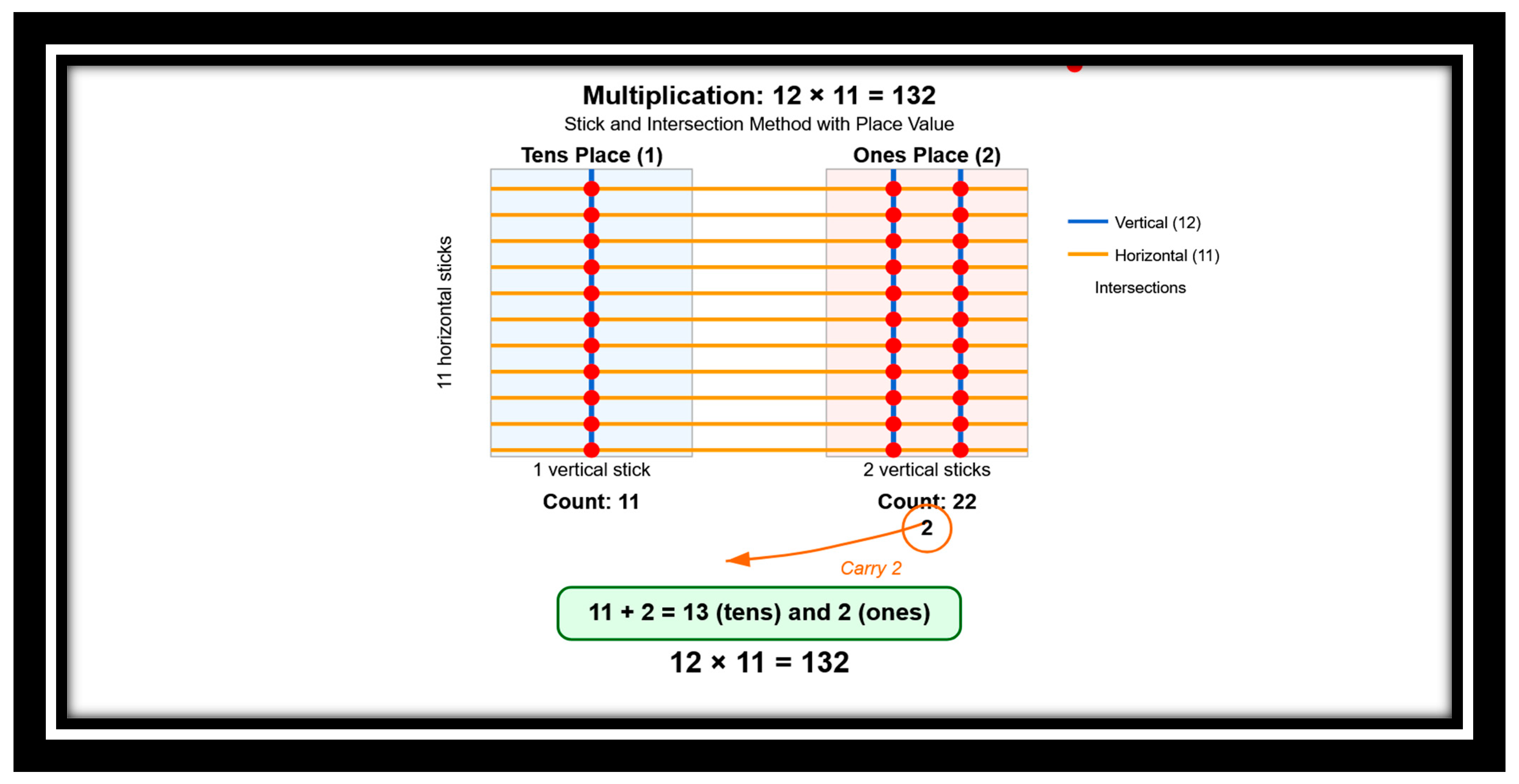

Example 5: 12 × 11

- Draw 1 vertical stick on the left side to represent the tens place (1).

- Draw 2 vertical sticks on the right side to represent the ones place (2).

- These are clearly separated into two sections to show place value.

- In the tens place (left section): 11 intersection points (1 vertical stick × 11 horizontal sticks).

- In the ones place (right section): 22 intersection points (2 vertical sticks × 11 horizontal sticks).

- The ones place has 22 dots: Write “2” in the ones place and carry “2” to the tens place.

- The tens place has 11 dots, plus the carried 2, giving 13: Write “13” (which becomes “1” in the hundreds place and “3” in the tens place).

- The final answer is 132 (12 × 11 = 132).

5. Results

5.1. Quantitative Findings

| Multiplication Type | Pre-Test Accuracy (%) | Post-Test Accuracy (%) | Improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-digit | 40.0 | 92.0 | 52.0 |

| Two by one-digit | 26.7 | 82.2 | 55.5 |

| Single by two-digits | 17.8 | 75.6 | 57.8 |

| Two by two-digits | 8.9 | 71.1 | 62.2 |

| Overall | 23.4 | 80.2 | 56.8 |

| Multiplication Type | t-Value | df | p-Value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-digit | 7.92 | 44 | <0.001 | 1.18 |

| Two by one-digit | 8.45 | 44 | <0.001 | 1.26 |

| Single by two-digits | 9.03 | 44 | <0.001 | 1.35 |

| Two by two-digits | 9.67 | 44 | <0.001 | 1.44 |

| Overall | 8.76 | 44 | <0.001 | 1.31 |

| Skill | Pre-Test (%) | Post-Test (%) | Improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic multiplication facts recall | 53.3 | 88.9 | 35.6 |

| Understanding of multiplication concept | 44.4 | 91.1 | 46.7 |

| Place value understanding in multiplication | 25.0 | 82.2 | 57.2 |

| Application to word problems | 31.1 | 77.8 | 46.7 |

| Self-correction ability | 17.8 | 84.4 | 66.6 |

| Computation accuracy | 35.6 | 86.7 | 51.1 |

| Multiplication Type | Post-Test (%) | One-Month Follow-Up (%) | Retention Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-digit | 92.0 | 88.9 | 96.6 |

| Two by one-digit | 82.2 | 77.8 | 94.6 |

| Single by two-digits | 75.6 | 71.1 | 94.0 |

| Two by two-digits | 71.1 | 66.7 | 93.8 |

| Overall | 80.2 | 76.1 | 94.9 |

| Initial Performance Level | Pre-Test (%) | Post-Test (%) | Improvement (%) | Effect Size (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower tercile (n = 15) | 10.7 | 72.0 | 61.3 | 1.87 |

| Middle tercile (n = 15) | 22.7 | 80.0 | 57.3 | 1.42 |

| Upper tercile (n = 15) | 36.7 | 88.7 | 52.0 | 1.05 |

5.2. Qualitative Findings

5.2.1. Student Engagement

5.2.2. Conceptual Understanding

5.2.3. Student Perceptions

- Accessibility: 87% of interviewed learners described the method as “easier to understand” than conventional approaches.

- Confidence: 73% reported increased confidence in their multiplication skills.

- Verification: 91% valued the ability to verify their answers by counting the intersection points.

- Enjoyment: 84% described mathematics as “more fun” when using the visual method.

- ✓

- “I can see the answer now instead of just guessing.”

- ✓

- “When I make a mistake, I can find it by counting again.”

- ✓

- “I like that I can do it myself without memorizing.”

5.3. Challenges and Limitations

- Time efficiency: For larger numbers, drawing and counting intersections became time-consuming. Some learners developed shortcuts, such as organizing dots into groups of five or ten for easier counting.

- Transition to mental models: Some learners initially relied heavily on the physical representation and needed scaffolding to internalize the visual model for mental computation.

- Application to larger multipliers: The current study focused on single-digit and two-digit multipliers. Extending the method to multi-digit multipliers (e.g., 243 × 36) would require additional instructional strategies.

- Transition to advanced concepts: While effective for whole number multiplication, students will eventually need to transition to array models and other representations that extend to fractions, decimals, and algebraic concepts. Teachers should be mindful of scaffolding this transition to prevent over-reliance on the stick intersection method.

6. Discussion

Scalability and Implementation Considerations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adler, J. (2002). Teaching mathematics in multilingual classrooms. Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Age, T. J., & Machaba, M. F. (2023). Effect of mathematical software on senior secondary school students’ achievement in geometry. Eureka: Social and Humanities, 5, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcavi, A. (2003). The role of visual representations in the learning of mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 52(3), 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino, G., Anton, J., Sharma, K., Gelsomini, M., Giannakos, M., & Abrahamson, D. (2025). Hybrid teaching intelligence: Lessons learned from an embodied mathematics learning experience. British Journal of Educational Technology, 56(2), 621–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio, U. (2001). In my opinion: What is ethnomathematics, and how can it help children in schools? Teaching Children Mathematics, 7(6), 308–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Basic Education. (2014). Report on the annual national assessment of 2014. Department of Basic Education. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/REPORT%20ON%20THE%20ANA%20OF%202014.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Department of Basic Education. (2019). Mathematics teaching and learning framework for South Africa: Teaching mathematics for understanding. Department of Basic Education. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/MathematicsTeachingandLearningFramework.aspx (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Duval, R. (2006). A cognitive analysis of problems of comprehension in a learning of mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 61(1–2), 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleisch, B. (2008). Primary education in crisis: Why South African schoolchildren underachieve in reading and mathematics. Juta & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Fuson, K. C. (2003). Developing mathematical power in whole number operations. In J. Kilpatrick, W. G. Martin, & D. Schifter (Eds.), A research companion to principles and standards for school mathematics (pp. 68–94). National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert, J., & Carpenter, T. P. (1992). Learning and teaching with understanding. In D. A. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning: A project of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (pp. 65–97). Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hoadley, U. (2012). What do we know about teaching and learning in South African primary schools? Education as Change, 16(2), 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J. H., Taub, M., Marino, M., & Holman, K. (2025). Examining fraction performance and learning trajectories in students with learning disabilities: Effects of whole-class intervention. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamii, C., & Dominick, A. (1998). The harmful effects of algorithms in grades 1–4. In L. J. Morrow, & M. J. Kenney (Eds.), The Teaching and Learning of Algorithms in School Mathematics (Yearbook of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, pp. 130–140). NCTM. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, J., Swafford, J., & Findell, B. (2001). Adding it up: Helping children learn mathematics. National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G., & Núñez, R. E. (2000). Where mathematics comes from: How the embodied mind brings mathematics into being. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Machaba, F. M. (2018). Pedagogical demands in mathematics and mathematical literacy: A case of mathematics and mathematical literacy teachers and facilitators. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 14(1), 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosimege, M., & Onwu, G. (2004). Indigenous knowledge systems and science and technology education: A dialogue. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 8(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2000). Principles and standards for school mathematics. NCTM. [Google Scholar]

- Presmeg, N. (2006). Research on visualization in learning and teaching mathematics. In A. Gutiérrez, & P. Boero (Eds.), Handbook of research on the psychology of mathematics education (pp. 205–235). Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, V., Visser, M., Winnaar, L., Arends, F., Juan, A., Prinsloo, C., & Isdale, K. (2016). TIMSS 2015: Highlights of mathematics and science achievement of grade 9 South African learners. Human Sciences Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. [Google Scholar]

- Setati, M. (2005). Teaching mathematics in a primary multilingual classroom. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 36(5), 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setati, M., & Adler, J. (2000). Between languages and discourses: Language practices in primary multilingual mathematics classrooms in South Africa. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 43, 243–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaull, N., & Kotze, J. (2015). Starting behind and staying behind in South Africa: The case of insurmountable learning deficits in mathematics. International Journal of Educational Development, 41, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffe, L. P. (1994). Children’s multiplying schemes. In G. Harel, & J. Confrey (Eds.), The development of multiplicative reasoning in the learning of mathematics (pp. 3–39). State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Svraka, B., & Ádám, S. (2024). Examining mathematics learning abilities as a function of socioeconomic status, achievement and anxiety. Education Sciences, 14, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N., & Taylor, S. (2013). Teacher knowledge and professional habitus. In N. Taylor, S. van der Berg, & T. Mabogoane (Eds.), Creating effective schools (pp. 202–232). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Venkat, H., & Spaull, N. (2015). What do we know about primary teachers’ mathematical content knowledge in South Africa? An analysis of SACMEQ 2007. International Journal of Educational Development, 41, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergnaud, G. (1983). Multiplicative structures. In R. Lesh, & M. Landau (Eds.), Acquisition of mathematics concepts and processes (pp. 127–174). Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Way, J., & Ginns, P. (2024). Embodied learning in early mathematics education: Translating research into principles to inform teaching. Education Sciences, 14(7), 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, L., & Webb, P. (2004). Eastern Cape teachers’ beliefs of the nature of mathematics: Implications for the introduction of in-service mathematical literacy programmes for teachers. Pythagoras, 60, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Age, T.J.; Machaba, M.F. Visual Multiplication Through Stick Intersections: Enhancing South African Elementary Learners’ Mathematical Understanding. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101383

Age TJ, Machaba MF. Visual Multiplication Through Stick Intersections: Enhancing South African Elementary Learners’ Mathematical Understanding. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101383

Chicago/Turabian StyleAge, Terungwa James, and Masilo France Machaba. 2025. "Visual Multiplication Through Stick Intersections: Enhancing South African Elementary Learners’ Mathematical Understanding" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101383

APA StyleAge, T. J., & Machaba, M. F. (2025). Visual Multiplication Through Stick Intersections: Enhancing South African Elementary Learners’ Mathematical Understanding. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101383