Abstract

This study examines educators’ perceptions of diversity in promotional practices within the Irish context through the lens of Gender Schema Theory (GST). Although women constitute the majority of the teaching workforce, they remain underrepresented at senior leadership levels, highlighting persistent gender disparities. Using survey data from 123 educators, this study investigates how gender shapes perceptions of the role of diversity in promotion processes. Findings indicate that women were more likely than men to perceive diversity across multiple dimensions as essential to fair and effective promotions and to enhancing leadership effectiveness. By contrast, men were more inclined to perceive current practices as already fair and inclusive and preferred to maintain the status quo. Importantly, tokenism was not strongly endorsed by either group, suggesting that diversity initiatives are broadly regarded as legitimate. The results underscore how gendered schemas influence perceptions of merit and fairness and highlight the importance of embedding transparent and inclusive structures in leadership promotion within Irish education.

1. Introduction

Equity, diversity, and inclusion in educational leadership have become central concerns as schools seek to reflect the societies they serve (Chaaban et al., 2025). Although women comprise the majority of the teaching workforce, men continue to occupy a disproportionate share of senior leadership roles (Gaus et al., 2023). This imbalance raises questions of fairness in promotional practices and underscores the persistence of barriers to progression in education. Research shows that culturally responsive and inclusive school leadership can improve outcomes for marginalised pupils (Khalifa et al., 2016), and that teachers themselves perform better under supervisors with shared backgrounds (Grissom & Keiser, 2011), suggesting that representative leadership benefits both staff and students.

Leadership representation also matters for the implicit messages it communicates to pupils. Seeing leaders who reflect their own gender, ethnicity, or background can encourage pupils to view themselves in similar positions and to set ambitions that align with their potential (Laiduc et al., 2021). When those in authority come from a limited demographic, it suggests that leadership is reserved for particular groups, which may deter others from aspiring to such roles (Homan & Abbaszadeh, 2025). Having diverse role models in positions of responsibility provides a visible reminder that leadership is open to all (Fritz & van Knippenberg, 2019; Tillman, 2004), helping to shape pupils’ sense of belonging and fairness within schools. This symbolic aspect of leadership complements the more practical advantages of inclusive practice and highlights the wider importance of ensuring representation at senior levels of education.

1.1. Aims and Objectives

The aim of this study is to investigate how gendered perceptions shape understandings of diversity in leadership promotions within Irish primary and post-primary schools. Specifically, it seeks to determine whether men and women differ in how they perceive the significance of eight dimensions of diversity (age, disability, gender, national origin and culture, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, social class, and religion) in promotional processes (Chui et al., 2015).

The objectives of the study are:

- To examine how educators perceive the role of eight diversity dimensions in leadership promotions.

- To assess gendered differences in the prioritisation of diversity dimensions.

- To explore whether educators believe the prioritisation of diversity enhances leadership effectiveness and school performance.

1.2. Background

The underrepresentation of women in leadership has often been described as a “glass ceiling”, whereby structural and cultural factors limit access to senior roles (Babic & Hansez, 2021). In education, this phenomenon is particularly visible given the dominance of women in teaching, contrasted with their reduced presence as principals and deputy principals (Gaus et al., 2023). Barriers include implicit bias, limited access to professional networks, and expectations regarding family and work responsibilities (Babic & Hansez, 2021; Duxbury & Higgins, 1991; Freeman, 1990). Historically, promotional processes have reflected established norms of authority that favoured male candidates (Acker, 1990; Hodgins & O’Connor, 2021; O’Connor, 2020), contributing to systemic imbalance despite growing female participation in the profession.

Recent years have seen increasing attention to equity, diversity, and inclusion in educational policy (OECD, 2023). Schools are expected to deliver academic instruction but also to model fairness and opportunity. Diverse leadership teams contribute broader perspectives and foster inclusive cultures (Murwanto, 2024). Discourse aimed at redressing gender imbalance and supporting minority representation has become more prominent, yet concerns remain that diversity initiatives can be reduced to tokenistic measures (Emma, 2024; Johnson & Bornstein, 2020; Salazar Montoya, 2024). Appointments made to satisfy numerical targets risk undermining confidence in promotional practices unless accompanied by transparent criteria and genuine commitment.

While gender and race have been the most visible focus of research, other dimensions of diversity also shape leadership dynamics. Age, disability, national origin and culture, religion, social class, and sexual orientation all influence the opportunities available to educators. Understanding how these dimensions put forward by Chui et al. (2015) are perceived in promotional processes is essential to building leadership structures that are equitable and effective. This paper will present an analysis by examining gendered perceptions across all eight dimensions of diversity outlined by Chui et al. (2015). By focusing on how men and women educators within primary and post-primary settings in the Republic of Ireland perceive and value (i) age, (ii) disability, (iii) gender, (iv) national origin and cultural, (v) racial and ethnicity, (vi) sexual orientation, (vii) social class and (viii) religious diversity dimensions, this study seeks to identify where perceptual differences are most pronounced. This approach makes it possible to understand whose perceptions of diversity are broader or more expansive. In doing so, this paper aims to shed light on how gendered perspectives shape the recognition of diversity in promotional processes and the implications this has for building leadership structures that are both equitable and representative.

Despite a substantial body of research on representation in leadership (Akinola & Naidoo, 2024; Easley, 2023; Lukkien et al., 2024; Scott et al., 2023), there is less evidence on how teachers and leaders themselves perceive various diversity dimensions within promotions. Much of the existing work has centred on race and gender or indeed the intersectionality of the two (Bush & Glover, 2016; Crawford & Fuller, 2015; Méndez-Morse et al., 2015; Miller, 2016; Suter, 2017). This limits the understanding of the extent to which other diversity dimensions are explored in detail. Perceptions of fairness are particularly important, as they influence not only trust in leadership structures but also motivation and engagement among educators. It is also important to recognise that young people are influenced by the individuals they see occupying positions of authority through Social Learning Theory as posited by Bandura (1977). The visibility of diverse leaders sends a powerful message about who can hold responsibility and helps shape pupils’ perceptions of opportunity and belonging (Fritz & van Knippenberg, 2019; Tillman, 2004).

This study addresses these gaps by examining how educators perceive the role of eight different diversity dimensions in promotional practices within Irish schools. Using a quantitative survey approach, it explores (i) whether diversity dimensions are currently prioritised, (ii) whether they should be prioritised, (iii) whether prioritisation is seen as enhancing school performance and leadership effectiveness through gendered differences in these perceptions, and (iv) opinions surrounding tokenistic hiring practices. In doing so, this study is among the first to investigate educators’ perceptions of leadership promotions across multiple diversity dimensions, offering a more holistic understanding of equity and inclusion in the Irish educational context.

1.3. Context

In the Republic of Ireland, issues of workload and wellbeing among school leaders are particularly acute, with principals frequently reporting unsustainable stress levels and limited work–life balance (Burke & Dempsey, 2021; McHugh, 2023). The Irish teaching workforce also reflects the demographic profile of the wider society, which is predominantly white, Irish, and Catholic, especially at the primary level, where the vast majority of teachers are white Irish females (Connolly et al., 2023; Foxe, 2024). Yet, the pupil population is becoming increasingly diverse, with approximately one in five pupils having an immigrant background and almost one third speaking a language other than English or Irish at home (Devine et al., 2025). This demographic shift highlights a growing disconnect between the composition of school staff and the communities they serve. A lack of workforce diversity in education has implications for equity and representation, while also restricting the leadership pipeline for minority groups and limiting the benefits of varied perspectives (Perrone, 2022; Travers & King, 2025).

1.4. Rationale for Study

This study is timely because national and sectoral frameworks increasingly emphasise the importance of diversity in leadership. Action 2.1 of the National Action Plan Against Racism (Department of CEDIY, 2024) commits to expanding access for minority ethnic groups to leadership positions by 2027. However, in terms of the other diversity dimensions, at the legislative level, the Employment Equality Acts 1998–2015 require all employers, including schools, to ensure fair, transparent, and non-discriminatory recruitment processes (Citizens Information, 2023). Many schools, or school groups such as Education and Training Boards, have Equality, Diversity and Inclusion policies reflecting these obligations. However, little is known about how teachers and leaders in the Republic of Ireland perceive different diversity dimensions in relation to promotions—whether they are prioritised, should be prioritised, and how they impact school performance and leadership effectiveness. This study addresses that gap, applying Chui et al.’s (2015) eight dimensions of diversity.

1.5. Theoretical Framework

Gender Schema Theory (GST) provides a useful framework for understanding why men and women differ in their perceptions of leadership opportunities for diverse candidates (Table 1). Introduced by Bem (1981), GST argues that individuals internalise cultural and social expectations of gender into cognitive structures known as “schemas”, which organise knowledge, influence information processing, and regulate behaviour (Bem, 1981). These schemas emerge early in life through socialisation and act as filters, shaping attention, memory, and evaluation of information in ways that reinforce culturally defined gender norms (Bem, 1981). In educational leadership, this could mean that views on diversity are shaped by gendered perspectives, which in turn affect how people conceptualise fairness, merit, and inclusion. Contemporary reviews of GST demonstrate that it remains widely cited and influential, extending beyond psychology into domains such as occupational stereotyping and organisational behaviour (Starr & Zurbriggen, 2016). This makes GST particularly relevant for studies of promotion practices, as gendered schemas may explain why men and women prioritise diversity dimensions differently. Such differences, grounded in cognitive processing as much as in social structures, underline the importance of examining gendered perspectives when assessing the legitimacy and impact of equity initiatives in leadership contexts.

Table 1.

Core tenets of the Gender Schema Theory (GST).

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a quantitative, cross-sectional survey design to examine perceptions of gender diversity in promotional practices within educational settings. Data were collected using an online questionnaire distributed via Qualtrics, a GDPR-compliant platform. Participants were recruited through social media posts and encouraged to share the survey with colleagues in the profession, facilitating a snowball sampling approach.

A total of 123 complete responses were obtained. The survey instrument consisted primarily of Likert-scale items (1 = Strongly Agree, 5 = Strongly Disagree), alongside four open-ended questions at the end to allow for qualitative elaboration. Higher mean scores, therefore, indicate lower levels of agreement with the statements. Three types of statements were used: (i) whether each diversity dimension is currently prioritised in promotions, (ii) whether it should be prioritised, and (iii) whether prioritising it has a positive impact on school performance and leadership effectiveness. No formal definitions of school performance or leadership effectiveness were provided; participants were asked to respond based on their own understanding and professional experience. For this study, the authors have only presented the results of the Likert-scale items. The diversity dimensions assessed were adopted from Chui et al. (2015) and categorised into three thematic sections: (i) whether each diversity dimension is currently prioritised in promotions, (ii) whether it should be prioritised, and (iii) whether prioritising it positively impacts school performance and leadership effectiveness.

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the University of Limerick Education and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (approval code: 2024_12_26_EHS). All participants received a participant information sheet and provided informed consent. Anonymity and confidentiality were assured throughout.

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS (version 29.0.2.0). Descriptive statistics were used to summarise participant responses through mean and standard deviation figures. One-way ANOVA tests were performed to examine differences across both gender groups. Effect sizes (partial η2) were calculated to provide context regarding the strength of associations.

3. Results

In this section the results of the descriptive statistics (Table 2), means and standard deviation tables, and ANOVA outcomes will be presented.

Table 2.

Demographics of participants.

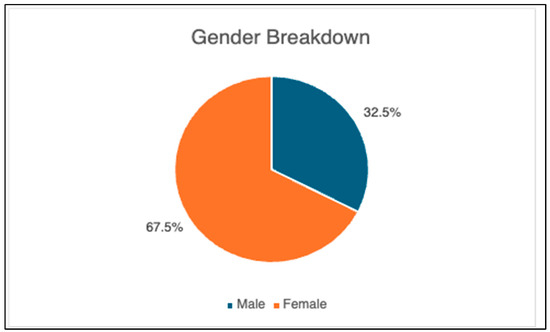

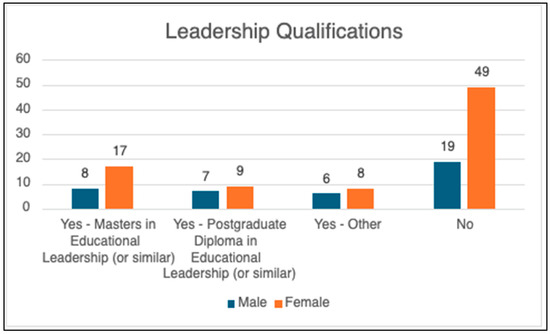

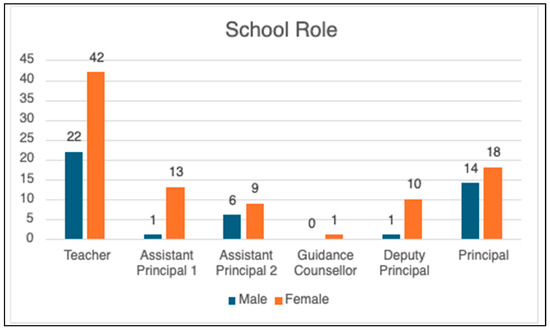

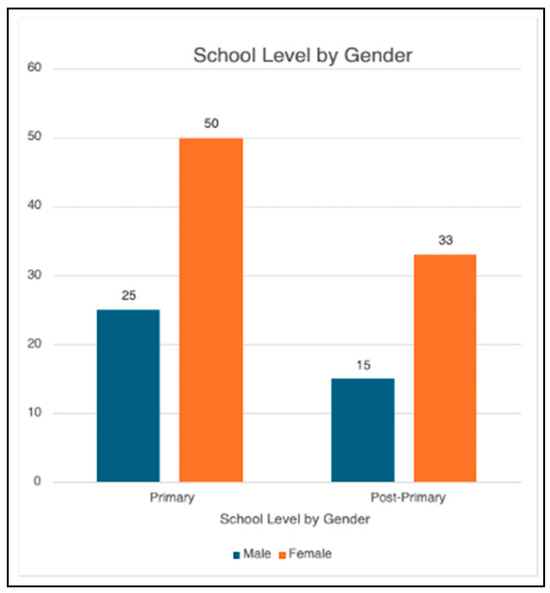

The data presented in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 shows that female participants make up the majority, accounting for 67.5% compared to 32.5% male participants. For a broader perspective, males make up around 21% of the education workforce in Ireland, accounting for both primary (15%) and post-primary (32%) level. Turning attention to the most senior school role of principal, males account for approximately 34% of primary school principals and 55% of post-primary school principals, far outweighing their gender share of the general educational workforce (Department of Education and Youth, 2025). At both the primary and post-primary school levels, females outnumber males, with the gap being largest at the primary level, where there are twice as many females (50) as males (25). In terms of school roles, females dominate across most categories. The majority of teachers are female (42 compared to 22 males), and females also hold more leadership positions, such as Assistant Principals, Deputy Principals, and Principals. It is worth noting that a participant can hold two roles, such as being both a teacher and an assistant principal, which may explain some of the overlaps in role distribution. For example, there are 22 female Assistant Principals (Level 1 and 2) compared to just seven males, and 10 female Deputy Principals compared to only one male. The Principal role is more balanced but still female-leaning, with 18 females compared to 14 males. Interestingly, the role of Guidance Counsellor is almost absent, represented by just one female. Overall, the breakdown highlights a strong female majority both in numbers and in leadership positions across school levels, but it should be noted that despite comprising a 67.5% majority in the overall survey numbers, females only account for ~56% of the top senior leadership positions—the role of principal.

Figure 1.

Gender breakdown.

Figure 2.

Leadership qualifications by gender.

Figure 3.

School role by gender. N.B. A participant can hold two positions, such as Assistant Principal and Teacher.

Figure 4.

School level by gender.

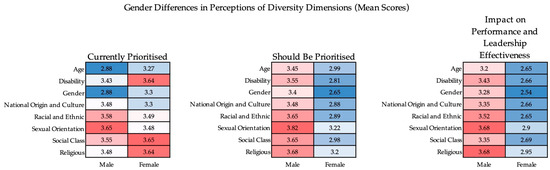

Descriptive statistics (Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6) highlighted notable gender differences in how diversity dimensions were prioritised for promotions. Asterisks were used throughout to denote the gender that had the lower mean score, therefore indicating more agreeability. For age diversity, males reported stronger agreement (M = 2.88, SD = 1.20) than females (M = 3.27, SD = 1.12). A similar pattern emerged for disability diversity (M = 3.43, SD = 0.93 for males; M = 3.64, SD = 0.88 for females), gender diversity (M = 2.88, SD = 1.14 for males; M = 3.30, SD = 0.97 for females), and social class diversity (M = 3.55, SD = 1.06 for males; M = 3.65, SD = 0.95 for females). Males also expressed slightly stronger agreement on religious diversity (M = 3.48, SD = 1.09) compared to females (M = 3.64, SD = 0.89). Conversely, females rated several other dimensions more highly. For national origin and cultural diversity, females reported stronger agreement (M = 3.30, SD = 0.91) compared to males (M = 3.48, SD = 1.06). A similar trend was seen in racial and ethnic diversity (M = 3.49, SD = 0.93 for females; M = 3.58, SD = 1.06 for males) and in sexual orientation diversity (M = 3.48, SD = 0.92 for females; M = 3.65, SD = 1.00 for males). Across the broader set of items, females consistently agreed more strongly than males that all diversity dimensions should be prioritised, that such prioritisation enhances school performance and leadership effectiveness, and that tokenism undermines the effectiveness of EDI initiatives. Heatmaps (Figure 5) were presented to underscore the differentials between the two sets of gender within the study. The lower the value, the more agreeable the participants were with the statement. Blue represents agreeable, red represents non-agreeable.

Table 3.

Means and standard deviation for diversity dimensions are prioritised in promotions.

Table 4.

Means and standard deviation for diversity dimensions should be prioritised in promotions.

Table 5.

Means and standard deviation for prioritising diversity dimension in promotions positively impacts school performance and leadership effectiveness.

Table 6.

Means and standard deviation for tokenistic practices.

Figure 5.

Heatmap for gender differences in perceptions of diversity dimensions (mean scores across “currently prioritised”, “should be prioritised”, “impact on performance and leadership effectiveness”. Each heatmap has been displayed on its own merits to distinctly demonstrate the difference of scores, they have not been compared to one another for the purpose of these graphics, blue indicating the lower mean score i.e., “more agreeable”, red indicating a higher mean score i.e., “less agreeable”).

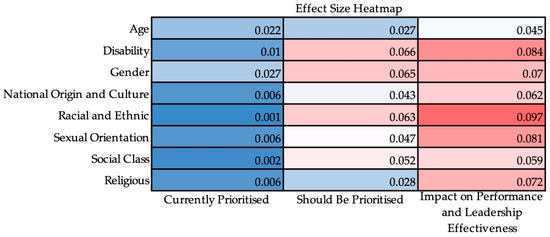

The ANOVA analyses (Table 7) revealed several significant gender effects in perceptions of diversity prioritisation in promotions. Disability diversity was rated as significantly more important by one gender group, F(1,121) = 8.55, p = 0.004, partial η2 = 0.066, reflecting a medium effect. Similar medium effects were found for gender diversity, F(1,121) = 8.47, p = 0.004, partial η2 = 0.065, and for racial and ethnic diversity, F(1,121) = 8.20, p = 0.005, partial η2 = 0.063. National origin and cultural diversity also showed a significant difference, F(1,121) = 5.44, p = 0.021, partial η2 = 0.043, alongside sexual orientation diversity, F(1,121) = 5.93, p = 0.016, partial η2 = 0.047, and social class diversity, F(1,121) = 6.65, p = 0.011, partial η2 = 0.052, all indicating small-to-medium effects.

Table 7.

ANOVA testing of diversity dimensions between males and females.

When examining perceptions of the impact of diversity on school performance and leadership effectiveness, significant gender differences were again evident. Disability diversity, F(1,121) = 11.14, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.084, gender diversity, F(1,121) = 9.11, p = 0.003, partial η2 = 0.070, racial and ethnic diversity, F(1,121) = 12.95, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.097, sexual orientation diversity, F(1,121) = 10.68, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.081, and religious diversity, F(1,121) = 9.36, p = 0.003, partial η2 = 0.072, all showed moderate effects. National origin and cultural diversity also reached significance, F(1,121) = 8.05, p = 0.005, partial η2 = 0.062, while age diversity, F(1,121) = 5.69, p = 0.019, partial η2 = 0.045, and social class diversity, F(1,121) = 7.52, p = 0.007, partial η2 = 0.059, reflected smaller but still meaningful effects.

Overall, the findings suggest that gender differences in perceptions of which diversity dimensions should be prioritised, and how they contribute to school outcomes, are consistently significant, with effect sizes ranging from small to moderate in magnitude. This has been represented through the medium of a heatmap (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Heatmap for effect sizes in perceptions of diversity dimensions (mean scores across “currently prioritised”, “should be prioritised”, “impact on performance and leadership effectiveness”).

4. Discussion

The findings of this study underscore a persistent paradox in Irish education: although women dominate numerically within the teaching profession, they remain disproportionately underrepresented in senior leadership positions (Department of Education and Youth, 2025). Gender Schema Theory (GST) provides a valuable framework for understanding this disparity, highlighting how internalised schemas shape perceptions, behaviours, and outcomes in ways that reinforce established gender norms (Bem, 1981). These schemas, acquired early through socialisation, function as cognitive filters that shape how individuals perceive merit, fairness, and suitability for leadership roles (Bem, 1981). The study reveals perceptual gaps between men and women in relation to diversity. Male respondents were more likely to report that diversity is already embedded in promotional practices (five from eight diversity dimensions), while female respondents expressed stronger agreement that diversity should be prioritised and would enhance leadership effectiveness (eight from eight diversity dimensions across both categories). Through the lens of GST, these differences reflect how schemas regulate information processing and evaluation. Women, more frequently encountering barriers to advancement, are likely to foreground inequities, whereas men, whose experiences align more closely with dominant schemas of leadership, tend to accept the status quo as legitimate (Acker, 1990). Effect size analyses reinforce this pattern. Gender differences were consistently small to moderate, with the largest gaps evident for disability, race and ethnicity, and sexual orientation. These findings suggest that women place greater emphasis on diversity dimensions that remain marginal within dominant cultural narratives of Irish schools. GST explains this by highlighting how schemas not only guide behaviour but also reinforce norms that privilege traditionally valued traits (Bem, 1981; Starr & Zurbriggen, 2016). Men, operating within schemas that align with conventional leadership stereotypes, may emphasise narrow criteria of merit, while women’s perspectives draw attention to wider equity concerns that challenge these stereotypes (Bem, 1981; Eagly & Carli, 2007; Eagly & Karau, 2002).

Interestingly, tokenism was not strongly endorsed by either group. Neither men nor women expressed significant concern that diversity initiatives undermine merit or result in token appointments, with tokenism in promotions undermining the credibility of diversity and inclusion efforts being the most agreed-upon statement on the Likert scale. At first glance, this suggests confidence in the legitimacy of current equity efforts. However, GST cautions that the absence of overt scepticism does not necessarily imply the absence of barriers (Bem, 1981). Schemas often function implicitly, influencing perceptions of leadership “fit” beneath conscious awareness (Bem, 1981; Eagly & Karau, 2002). The persistence of gender imbalance at senior levels, despite limited concern about tokenism, indicates that entrenched schemas, such as the privileging of agentic over communal leadership traits, may continue to reproduce unequal outcomes even when overt discrimination is not perceived (Bem, 1981; Eagly & Karau, 2002; Starr & Zurbriggen, 2016). The Irish sociocultural context provides further insight. Religious patronage and historical hierarchies of authority have long reinforced conventional schemas of leadership that privilege continuity and stability (Department of Education, 2022; Hodgins et al., 2022). While international discourse increasingly frames diversity as integral to effective governance, the Irish system may lag in embedding such values into everyday promotional practices (European Institute of Gender Studies, 2016; Hodgins et al., 2022). This could explain why female respondents identified a sharper gap between policy rhetoric and practice reality than their male counterparts. This study also contributes by examining multiple diversity dimensions simultaneously, moving beyond the narrower focus of gender and race. Women’s greater emphasis on disability, sexual orientation, and social class diversity underscores that equity concerns are multidimensional and interconnected. GST offers a useful explanation: schemas shape not only how individuals interpret their own identities but also how they perceive broader patterns of inclusion and exclusion (Bem, 1981). Women, whose experiences are more often marginalised within dominant schemas, may be especially attuned to the intersectional character of inequity (Bem, 1981; Crenshaw, 1989).

Several limitations must be acknowledged. The use of snowball sampling may have produced a sample disproportionately concerned with diversity, potentially inflating levels of awareness. The homogeneity of the Irish teaching profession is also prevalent here, and the small sample size may lead to generalisability. Reliance on self-report data restricts the ability to verify whether perceptions align with actual practices. Moreover, intersectional dimensions such as age, career stage, and school type were not explored in depth but may interact with gender to shape perspectives on equity. Future research should adopt mixed-methods and longitudinal approaches to capture how schemas evolve and to provide richer accounts of how promotional processes are experienced in practice. Overall, these findings highlight that while educators broadly support diversity and have neutral perceptions regarding promotions as tokenistic, significant gendered disparities in perceptions remain. Applying GST clarifies that schemas, formed early in life, reinforced by social norms, and reproduced through institutional practice, continue to influence how leadership is understood and enacted. Addressing these disparities requires interventions that move beyond procedural reform.

This study is important for the Republic of Ireland as it illuminates how diversity is perceived in the context of school leadership. In a rapidly diversifying society, understanding whether teachers and leaders view diversity as prioritised, whether it should be prioritised, and how it affects school performance and leadership effectiveness provides valuable insights for future policy and practice. This research highlights areas where further action is needed to ensure school leadership reflects and serves the increasingly diverse communities of the Republic of Ireland.

The implications for educational policy and practice are substantial. If schemas function as filters through which fairness and leadership potential are assessed, interventions must address these at a structural level. Hiring panels and Boards of Management could be trained to recognise and counteract gendered schemas, ensuring that criteria are not unconsciously aligned with male-coded leadership traits. Mentoring programmes could support underrepresented groups in navigating pathways to leadership, while systemic initiatives could validate a wider range of leadership styles. These measures must move beyond symbolic gestures and embed equity and inclusion as structural norms—not on a tokenistic level. Disrupting schemas that privilege traditional leadership stereotypes, Irish schools can make sustained progress towards equity in leadership representation.

5. Conclusions

This study examined educators’ perceptions of diversity in promotional practices in Irish schools through the lens of Gender Schema Theory (GST). A central paradox emerged: while women dominate the teaching profession numerically, they remain underrepresented at senior leadership levels. Men and women diverged in their views, with women more likely to emphasise the need to prioritise diversity across all dimensions and to view such prioritisation as enhancing leadership effectiveness. These differences suggest that women, more often confronted with barriers, are attuned to inequities, while men are more likely to accept existing norms as legitimate, perhaps as they have become the benefactors of the status quo. Importantly, both groups did not strongly endorse tokenism, indicating that diversity initiatives are broadly regarded as legitimate. Yet the persistence of imbalance despite this perception points to hidden schemas, such as the privileging of male-coded leadership traits, that continue to disadvantage women and other underrepresented groups.

A distinctive contribution of this study is its examination of multiple diversity dimensions, alongside the typically discussed dimensions of race and gender. Women’s greater emphasis on all diversity dimensions highlights the intersectional nature of equity concerns and demonstrates the value of applying GST to leadership research. While shaped by methodological limitations, the study underscores the need for promotion systems that challenge entrenched schemas as well as structural and historical barriers. Policies should move beyond symbolic inclusion by embedding transparent criteria, mentoring supports, and broader definitions of leadership that recognise diverse strengths. Sustained progress towards equity in Irish school leadership will depend on reshaping both institutional practices and the schemas that underpin them, ensuring that leadership pathways are legitimate, inclusive, and reflective of the diversity of contemporary society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.H. and N.L.; methodology, R.H. and N.L.; formal analysis, R.H.; investigation, R.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H., N.L. and P.M.-M.; writing—review and editing, R.H., N.L. and P.M.-M.; visualisation, R.H.; supervision, N.L. and P.M.-M.; project administration, N.L. and P.M.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a Government of Ireland Postgraduate Scholarship awarded by the Irish Research Council (grant number GOIPG/2024/5169).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research discussed in this paper received ethical approval from the Education and Health Sciences Ethics Department, University of Limerick. Approval number: 2024_12_26_EHS; date of approval: 8 January 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request due to restrictions placed on participant privacy; however, segments of the data can be requested by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GST | Gender Schema Theory |

References

- Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies. Gender & Society, 4(2), 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinola, D. A., & Naidoo, P. (2024). Breaking the glass ceiling: An examination of gendered barriers in school leadership progression in South Africa. Cogent Social Sciences, 10(1), 2395342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babic, A., & Hansez, I. (2021). The glass ceiling for women managers: Antecedents and consequences for work-family interface and well-being at work. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 618250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bem, S. L. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review, 88(4), 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J., & Dempsey, M. (2021). Wellbeing in post-COVID schools: Primary school leaders’ reimagining of the future. Maynooth University. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, T., & Glover, D. (2016). School leadership in West Africa: Findings from a systematic literature review. Africa Education Review, 13(3–4), 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaaban, Y., Badwan, K., & Arar, K. (2025). Educational leadership for social justice: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Review of Education, 13(2), e70077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, C. W. S., Kleinlogel, E. P., & Dietz, J. (2015). Diversity. Wiley Encyclopedia of Management, 6(1), 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citizens Information. (2023). Equality in the workplace. Citizens Information. Available online: https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/employment/equality-in-work/equality-in-the-workplace/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Connolly, M., James, C., & Murtagh, L. (2023). Reflections on recent developments in the governance of schools in Ireland and the role of the church. Management in Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E. R., & Fuller, E. J. (2015). A dream attained or deferred? Examination of production and placement of latino administrators. Urban Education, 52(10), 1167–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Available online: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8?utm_source=chicagounbound.uchicago.edu%2Fuclf%2Fvol1989%2Fiss1%2F8&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Department of CEDIY. (2024). National action plan against racism. GOV.ie. Available online: https://assets.gov.ie/static/documents/national-action-plan-against-racism.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Department of Education. (2022). Statistical bulletin—July 2022 overview of education 2001–2021. Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education and Youth. (2025). Teacher statistics. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/department-of-education/publications/teacher-statistics/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Devine, D., Bohnert, M., Greaves, M., Ioannidou, O., Sloan, S., Martinez-Sainz, G., Symonds, J., Moore, B., Crean, M., Davies, A., Barrow, N., Crummy, A., Gleasure, S., Samonova, E., Smith, K., Smith, A., Stynes, H., & Donegan, A. (2025). Children’s school lives (CSL): National longitdunal cohort study of primary schooling in Ireland. Migration and ethnicity in children’s school lives. NCCA. Available online: https://cslstudy.ie/downloads/CSL_8c_Migration-Ethnicity.pdf? (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Duxbury, L. E., & Higgins, C. A. (1991). Gender differences in work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(1), 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A. H., & Carli, L. L. (2007). Through the labyrinth: The truth about how women become leaders. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easley, J. (2023). Diversifying the American teacher workforce: Problematizing the past and building the future. Excelsior: Leadership in Teaching and Learning, 15(2), 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emma, L. (2024). Policy interventions to promote gender equality in education and workforce leadership. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387762435_Policy_Interventions_to_Promote_Gender_Equality_in_Education_and_Workforce_Leadership/references (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- European Institute of Gender Studies. (2016). Promoting gender equality in academia and research institutions. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications/promoting-gender-equality-academia-and-research-institutions-main-findings (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Foxe, K. (2024). 97% of people working in public jobs are ‘white Irish’, research shows. RTE. Available online: https://www.rte.ie/news/business/2024/0624/1456419-97-of-public-jobs-workers-are-white-irish-research/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Freeman, S. J. M. (1990). Managing lives: Corporate women and social change. University of Massachusetts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, C., & van Knippenberg, D. (2019). Gender and leadership aspiration: Supervisor gender, support, and job control. Applied Psychology, 69(3), 741–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaus, N., Larada, N., Jamaluddin, S., Paramma, M. A., & Karim, A. (2023). Understanding the emergence of females as leaders in academia: The intersections of gender stereotypes, status and emotion. Higher Education Quarterly, 77(4), 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J. A., & Keiser, L. R. (2011). A supervisor like me: Race, representation, and the satisfaction and turnover decisions of public sector employees. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 30(3), 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, M., & O’Connor, P. (2021). Progress, but at the expense of male power? Institutional resistance to gender equality in an Irish University. Front Sociol, 6, 696446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgins, M., O’Connor, P., & Buckley, L.-A. (2022). Institutional change and organisational resistance to gender equality in higher education: An Irish case study. Administrative Sciences, 12(2), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, A. C., & Abbaszadeh, Y. (2025). Obstacles for marginalized group members in obtaining leadership positions: Threats and opportunities. Current Opinion in Psychology, 62, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D. D., & Bornstein, J. (2020). Racial equity policy that moves implicit bias beyond a metaphor for individual prejudice to a means of exposing structural oppression. Journal of Cases in Educational Leadership, 24(2), 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, M. A., Gooden, M. A., & Davis, J. E. (2016). Culturally responsive school leadership. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1272–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiduc, G., Herrmann, S., & Covarrubias, R. (2021). Relatable role models: An online intervention highlighting first-generation faculty benefits first-generation students. Journal of First-Generation Student Success, 1(3), 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukkien, T., Chauhan, T., & Otaye-Ebede, L. (2024). Addressing the diversity principle–practice gap in Western higher education institutions: A systematic review on intersectionality. British Educational Research Journal, 51(2), 705–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, R. (2023). A six-component conceptualization of the psychosocial well-being of school leaders: Devising a framework of occupational well-being for Irish primary principals. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Morse, S., Murakami, E. T., Byrne-Jiménez, M., & Hernandez, F. (2015). Mujeresin the principal’s office: Latina school leaders. Journal of Latinos and Education, 14(3), 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P. (2016). ‘White sanction’, institutional, group and individual interaction in the promotion and progression of black and minority ethnic academics and teachers in England. Power and Education, 8(3), 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murwanto, P. (2024). Developing and practicing inclusive leadership in schools. Progres Pendidikan, 5(1), 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P. (2020). Why is it so difficult to reduce gender inequality in male-dominated higher educational organizations? A feminist institutional perspective. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 45(2), 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). Equity and inclusion in education: Finding strength through diversity. O. Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Perrone, F. (2022). Why a diverse leadership pipeline matters: The empirical evidence. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 21(1), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar Montoya, L. (2024). Equity, diversity and inclusion: What’s in a name? Seattle Journal for Social Justice, 22(3), 620–672. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, L. A., Bettini, E., & Brunsting, N. (2023). Special education teachers of color burnout, working conditions, and recommendations for EBD research. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 31(2), 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, C. R., & Zurbriggen, E. L. (2016). Sandra Bem’s gender schema theory after 34 years: A review of its reach and impact. Sex Roles, 76(9–10), 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, E. J. (2017). Social cultural factors influencing appointment of headteachers in primary schools in eldoret east sub-county, Kenya. Journal of Education and Practice, 8, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tillman, L. C. (2004). Chapter 4: African american principals and the legacy of brown. Review of Research in Education, 28(1), 101–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, J., & King, F. (2025). Social justice leadership in Irish schools: Conceptualisations, supports and barriers. Irish Educational Studies, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).