Abstract

The integration of industry and education serves as a critical pathway for improving the quality of talent training in higher vocational colleges and achieving high-quality employment for graduates. This study employs linear regression and moderating effect models to examine the impact of industry–education integration on employment quality in higher vocational institutions, using data from the 2024 Vocational Education Quality Annual Report from 689 higher vocational colleges in China. The results show an inverted “U” relationship between the integration level of industry and education and employment quality in higher vocational colleges. Moreover, teachers’ qualification level and curriculum development capacity negatively moderate this relationship. Additionally, the effect of the industry–education integration on employment quality is heterogeneous across the public and private institutions, and whether a college has been designated as a “Double High” institution. Therefore, efforts should be made to strengthen teachers’ practical teaching abilities and enhance curriculum adaptability, as well as to implement differentiated guidance and support policies to effectively improve graduates’ employment quality.

1. Introduction

Employment quality is central to the high-quality development of higher vocational education (Y. Wang & Dong, 2024). With the industrial transformation and upgrading and the structural change in the labor market, higher vocational graduates are faced with a dual dilemma of “difficulty in finding employment” and “difficulty in recruiting workers.” On the one hand, problems such as employment pressure, delayed employment, and frequent employment turnover are increasingly prominent (Hu et al., 2022). According to the Ministry of Education of China, over 11.7 million students graduated in 2024, placing significant employment pressure on the job market (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2024). On the other hand, emerging industries face difficulties in recruiting highly skilled technical workers, highlighting a pronounced mismatch between labor supply and demand (Y. Zhang, 2021). The national supporting policies, such as the national “14th Five-Year Plan for Employment Promotion” and “Opinions on Deepening the Reform of the Construction of Modern Vocational Education System,” identify the achievement of fuller and higher-quality employment as the core objective of vocational education reform. Given this context, it is of urgent practical importance and political significance to investigate the internal mechanisms and key conditions necessary for effectively enhancing the employment quality of higher vocational graduates in order to align with labor market demands.

With the ongoing technological revolution and industrial transformation, including rapid advances in artificial intelligence and the digital economy, industrial forms are evolving at an accelerated pace. Labor-market demand has shifted from quantity expansion to quality alignment, while upgrading domestic industrial chains has raised requirements for integrated innovation. At the same time, structural frictions in the traditional education system—most notably, curricula that lag behind industrial change—have become bottlenecks to high-quality development. Since 2014, China’s Ministry of Education has mobilized enterprises to collaborate with higher-education institutions on industry–academia programs designed to reform talent training in line with technological and industrial needs. In 2017, the General Office of the State Council issued the Several Opinions on Deepening Industry–Education Integration, elevating this agenda to a national development strategy. The policy calls for deeper industry–education integration, stronger connectivity among the education, talent, industrial, and innovation chains, and the effective conversion of high-quality social resources into educational inputs (X. Gong, 2024). Industry–education integration is the key approach to addressing the inconsistency between talent training in higher education and industrial demand (Ren et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2025). It supports the development of specialized academic programs, enhances institutional responsiveness to market needs, and plays a crucial role in improving the employment quality of graduates (L. Zhang, 2025). In-depth college-enterprise cooperation can significantly improve the employment rate, starting salary level, and job adaptability of graduates (Sun, 2023). However, at the practical level, significant heterogeneity remains in terms of the depth and breadth of industry-education integration across regions, the initiative of enterprises’ participation, and the driving effect on graduates’ employment quality (F. Gao & Zhang, 2020). In some areas, the industry and education integration is superficial, known as “Integration Without Real Fusion” and “enthusiastic colleges, indifferent enterprises” (Lei, 2022). These imbalances hinder the effective promotion of overall employment quality among graduates (P. Yang et al., 2023; L. Zhang, 2025).

The existing literature has laid a foundation for understanding the relationship between the integration of industry and education and employment quality. The integration of industry and education plays a positive role in promoting students’ employability through mechanisms such as improving students’ vocational ability, enhancing employment competitiveness, optimizing employment environment, and providing entrepreneurial support (Y. Wu, 2021; L. Wang et al., 2025). However, in practice, problems such as poor coordination of “government-enterprise-college”, misalignment of supply and demand between industry and education, and lack of supporting policies and evaluation systems (Miu, 2023; W. Gong, 2023; T. Li, 2025) have restricted the full play of its effectiveness, resulting in the mismatch between talent training and enterprise needs and insufficient employability of students (X. Zhou et al., 2019; Yu, 2023). Although practical paths such as optimizing cooperation mechanisms, improving policies and regulations, and stimulating endogenous motivation between colleges and enterprises have been proposed (Fang, 2023; Yan, 2025), existing research remains largely focused on the linear promotional relationship between industry-education integration and employment outcomes, as well as the obstacles that impede such integration from effectively boosting employment. However, there has been insufficient exploration of the complexity inherent in its operational mechanisms, as well as the varied manifestations of its effects across different types of institutions.

This study explores the nonlinear relationship between industry-education integration and employment quality in vocational education, which has important implications for workforce development and vocational education reform. The innovative contributions of this study are mainly reflected in the following three aspects: (1) We uncover an inverted “U” -shaped relationship between industry-education integration and employment quality and further identify a critical threshold. Beyond this threshold, excessive integration reduces, rather than enhances, employment quality. This challenges the prevalent linear assumption in existing literature. (2) We further demonstrate the mechanism through which industry–education integration influences employment quality. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the moderating effect within the industry–education integration and employment quality framework. Specifically, we show that teachers’ ability and curriculum development capacity function as moderating factors. These elements not only attenuate the inverted U-shaped effect of integration on employment quality but also shift the critical threshold to the right. This finding highlights that enhancing faculty quality and strengthening curriculum design provide a practical pathway to sustain the benefits of integration and optimize employment outcomes. (3) Heterogeneity analysis: We reveal the differentiated impacts of industry–education integration on employment quality across public versus private colleges and “Double High” colleges. These findings provide targeted policy implications for diverse educational contexts. Unlike most existing studies, which focus narrowly on limited heterogeneity dimensions, our analysis expands the scope by considering institutional types and development levels, thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of the varied effects of integration.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 outlines the conceptual framework and develops the research hypotheses. Section 3 presents the model specification and data sources. Section 4 reports the empirical results. Section 5 concludes with a discussion of the main findings and policy implications.

2. Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Impact of Industry and Education Integration on Employment Quality

“The Several Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Deepening the Integration of Industry and Education” outlined that the primary objectives for deepening industry-education integration include: progressively enhancing the participation of industries and enterprises in educational operations, improving the diversified educational system, comprehensively implementing college-enterprise collaborative education, and ultimately fostering an integrated and mutually reinforcing development paradigm between education and industries (State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2017). Industry-education integration is a model in which vocational schools actively establish or partner with industry-specific enterprises aligned with their academic programs, closely intertwining industry operations with teaching activities (Shi & Hao, 2025). This approach creates mutual reinforcement between education and industry, transforming the school into an industrial-operational entity that integrates talent cultivation, scientific research, and technological services (H. Zhou & Yue, 2025). In doing so, it fosters a seamless partnership between schools and enterprise.

First, in the early stages of integration, colleges and enterprises can achieve a significant resource complementary effect through cooperative approaches like sharing training bases. On the one hand, enterprise internships provide students with practical experience that enhances their resumes and increases their alignment with job market demands (S. Xie, 2020). This closed-loop design of “learning-practice-employment” significantly enhances students’ employment competitiveness (D. Huang & Du, 2019; F. Xu, 2011). On the other hand, the integration of industry and education supports the cultivation of students’ innovation and entrepreneurial ability by implementing innovative elements and entrepreneurial scenarios (Xiao, 2021; Z. Xu, 2025).

Second, from the perspective of information economics, this collaborative mode directly reduces the information search cost and matching cost of talent supply and demand sides, and enables students to complete the transformation of “theoretical knowledge-practical skills” in real industry scenarios (Y. Wu, 2021). On the one hand, as the core carrier of the integration of industry and education, the on-campus productive training base can improve the social adaptability of students’ professional skills (D. Wang & Zhao, 2014), reduce the psychological stress in the workplace, and improve the employment quality through the entry of enterprise quality management standards. On the other hand, “order-class” initiatives1 and related approaches enable a more accurate matching of talent cultivation with specific employment needs (H. Chen, 2021). Such programs help to bridge the gap between traditional education and workplace demands, strengthen the cultural identity of enterprises, and reduce employee turnover. Under this mechanism, employment quality demonstrates increasing marginal returns in the initial phase of integration.

While early-stage industry–education integration helps align curricula with industry needs, excessive enterprise participation can simplify instruction and produce the tipping point we estimate. This occurs through several mechanisms. First, under bounded rationality and incentive incompatibility, firms facing short-term production pressures minimize training costs; the locally optimal choice is to place students on existing production lines rather than invest in costly, personalized instruction, crowding out higher-order learning and theory (Chai, 2020). Second, college-enterprise cooperation is governed by incomplete contracts, so many quality requirements cannot be specified or enforced ex ante (Q. Yang & Li, 2025). As integration deepens, communication, monitoring, and transaction costs rise, and opportunistic behavior—such as using internships as low-cost labor—becomes a rational response, degrading talent cultivation and employment quality (Miu, 2023; Wan, 2019). Third, beyond a threshold, weaknesses in the government–enterprise–college coordination mechanism emerge: fragmented policies and weak supervision/evaluation generate uneven quality and, at times, rights infringements (Z. Zhang, 2022; S. Ma & Guo, 2018; Wan, 2019). Finally, goal misalignment persists; firms optimize for near-term job readiness while universities must build long-term capacities, yielding “superficial integration” that prioritizes repetitive task training over core competencies (B. Yang & Dai, 2018; Zheng, 2015). Taken together, these forces are consistent with the expectation that inter-organizational transaction costs increase with cooperative complexity, shifting integration from learning-complementary activities to production substitution and, ultimately, generating the tipping point. Based on this, we developed Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1.

There is an inverted U-shaped relationship between the level of industry–education integration and employment quality, such that moderate integration enhances employment outcomes, while too much integration leads to diminishing or negative returns.

2.2. The Moderating Effect of Teacher Qualification Level

Faculty play an important role in the implementation of the industry–education integration model in higher education (H. Wang, 2020). This study uses the proportion of teachers with senior professional titles as a core measure of faculty quality; an approach grounded in the professional title evaluation system of China’s higher vocational institutions. First, earning a senior professional title represents a comprehensive and authoritative certification of a teacher’s research capability, teaching competence, industry engagement, and practical experience. According to the Regulations on Enterprise Practice for Vocational School Teachers (Ministry of Education et al., 2018), and the Measures for Promoting School-Enterprise Cooperation in Vocational Schools (Ministry of Education et al., 2018), all faculty in vocational schools are required to complete an industry externship of at least one month per year or six months within a five-year cycle. Such enterprise practice is a mandatory criterion for professional title promotion among vocational college teachers; consequently, experienced teachers, therefore, accumulate substantial corporate experience and strong industry networks. This screening mechanism endows senior-title teachers with recognized qualifications, making them indispensable “stabilizers” within the industry-education integration system. According to signaling theory, a senior title acts as a strong, high-cost signal that is difficult to falsify, conveying reliable information to enterprises about the teacher’s and the program’s high academic credibility and resource integration capacity. On the one hand, highly titled teachers can better discern industrial trends and corporate talent needs, helping to prevent misalignment between talent cultivation and industry demands, particularly in updating teaching content within industry-education integration (L. Ma et al., 2025). On the other hand, in practice, highly titled teachers can help mitigate “information asymmetry” in the initial stages of college-enterprise cooperation, reducing search and trust costs for enterprises and laying the foundation for deeper and higher-quality collaboration (L. Lu & Deng, 2021).

Second, highly titled teachers are a scarce human resource in higher education institutions. When the level of industry-education integration exceeds a reasonable range, leading to issues such as insufficient motivation for enterprise participation and superficial collaboration, these teachers, equipped with solid theoretical foundations, cutting-edge technical perspectives, and industry experience accumulated through meeting title promotion requirements, can transform fragmented and short-term practical needs of enterprises into systematic curricula and talent development plans. This transformative capacity effectively mitigates the risks associated with excessive integration, such as reducing students to low-skilled labor and fragmenting their knowledge, thereby safeguarding the systematic and forward-looking nature of talent cultivation. Finally, teachers with senior titles often hold greater influence within departmental governance structures and can comprehend the dual institutional logics of “educational cultivation” and “industrial service.” When conflicts arise between the goals of colleges and enterprises, they can act as “institutional bridges.” By helping set cooperation standards, project-selection criteria, and quality-evaluation systems, they reshape collaborative norms, pulling potentially unmanageable market relations back into a controllable and efficient quasi-bureaucratic governance framework. Thereby, they curb the negative effects resulting from excessive integration. Based on this, we developed Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2.

The level of teacher qualifications negatively moderates the inverted U-shaped relationship between the level of industry–education integration and employment quality.

2.3. Moderating Effect of Curriculum Development Capacity

When the overexpansion of industry–education integration leads to fragmentation of practical resources provided by enterprises and a misalignment between training objectives and actual job requirements, high-quality curriculum development capacity—by virtue of its inherent systematicity and standardization—can play a critical moderating role.

First, based on the “structural functionalism” theory in curriculum development, high-level curriculum construction possesses a systematic integration function. It transforms scattered enterprise projects into structured curriculum modules (J. Zhang et al., 2021) and deconstructs industry standards into quantifiable skill-training indicators, thereby avoiding the fragmentation of knowledge transfer caused by indiscriminate expansion of industry–education integration. This helps maintain the integrity of students’ knowledge systems and their adaptability to job requirements.

Second, curriculum development capacity facilitates agile responsiveness to industrial changes through dynamic updating and feedback mechanisms. By leveraging the iterative process of curriculum renewal, it tracks the technological transformation within industries in real time, phases out practical content that lags behind sector development, and incorporates teaching modules on cutting-edge technologies (Y. Xie et al., 2019; He & Huang, 2025). This prevents the lagging nature of corporate resources within industry–education integration from undermining employability training.

Finally, from the perspective of educational ecology, the curriculum serves as a core medium for defining the boundaries between school and enterprise cooperation, thereby reconstructing the collaborative education framework. Using curriculum objectives as an anchor, it redefines the boundaries of college-enterprise collaboration, keeping the depth of enterprise involvement within the capacity of the curriculum system (Zhuang & Sun, 2024). This avoids overloading practical teaching tasks due to excessive integration. At the same time, by incorporating corporate job performance standards into the curriculum evaluation system, a closed-loop feedback mechanism is formed to monitor the quality of industry–education integration. Ultimately, this systematically mitigates the potential inhibitory effect of industry–education integration on employment quality and dynamically maintains a high-quality balance between talent cultivation and industrial demands. Based on this, we developed Hypothesis 3:

Hypothesis 3.

Curriculum development capacity negatively moderates the inverted “U” relationship between the integration level of industry and education and employment quality.

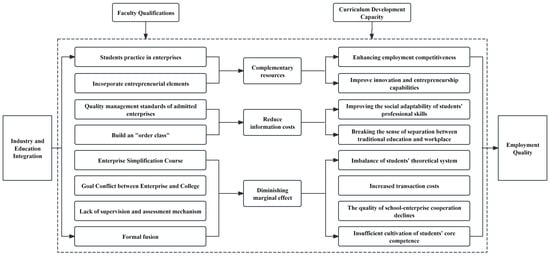

In summary, the level of industry–education integration influences employment quality, mediated by faculty qualifications and curriculum development capacity. Initially, an increase in industry-education integration helps reduce information asymmetry, encourages educational institutions to align skill training more closely with industry needs, and enhances the alignment between talent development and job requirements, thereby improving the Employment Quality. However, as the level of industry–education integration increases beyond a certain threshold, excessive integration may lead to diminishing or negative returns due to increased transaction costs, goal misalignment, and opportunistic behaviors, especially when teacher qualification and curriculum-development capacity lag behind the pace of integration. This results in an inverted U-shaped relationship between the level of industry-education integration and employment quality. Furthermore, the negative moderating effects of teacher qualification level and curriculum development capacity help mitigate the risks associated with excessive integration. Highly qualified teachers act as stabilizers and institutional bridges, ensuring educational quality and systematic training, while strong curriculum development capacity maintains the structure and relevance of educational content, thereby preserving employment quality even at high levels of integration. Figure 1 illustrates this underlying mechanism.

Figure 1.

Conceptional framework.

3. Model Specification and Data

This study focuses on analyzing the impact mechanism of the level of industry-education integration in higher vocational colleges and universities on employment quality, examining the moderating role of teacher qualification level and curriculum development capacity, as well as the heterogeneity of effects across different institutional characteristics, so as to provide references for optimizing vocational education practices and improving graduates’ employment quality.

3.1. Benchmark Model

In the main effect model, the square term of the integration level of industry and education is introduced to test the nonlinear relationship between the integration of industry and education and its employment quality. Following Zhao and Liu (2025) and Glavina et al. (2025), the benchmark regression model is:

In Equation (1), the explanatory variable is the employment quality level of college i, the explanatory variable is the integration level of industry and education of college i, and the variable of interest is . In order to avoid endogenous problems caused by missing variables, for control variables are introduced, including (1) dqt: Proportion of full-time teachers with “double-qualified” quality; (2) nfm: Proportion of new form teaching materials; (3) pjs: Number of practical teaching jobs per student on campus; (4) eqv: Value of teaching and scientific research instruments and equipment per student. is a random disturbance term, is an intercept term, and are corresponding estimated coefficients.

3.2. Moderating Effect Model

In the moderating effect model, following C. Ma and Li (2025)’s method of curve relationship, the quadratic interaction term and the primary interaction terms are included to test the moderating effect of teacher qualification level and curriculum development capacity. Specifically, we have:

In Equation (2), is the adjusting variable teacher qualification level, is the interaction term between teacher qualification level and industry -education integration level; is the interaction term between the teacher qualification level and the square term of the integration level of industry and education. is the intercept term; denotes their estimated coefficients, where . is a random error term, and the meanings of remaining variables are consistent with those in Model (1). If , it shows that the inflection point of the integration level of industry and education affecting employment quality will move to the right with the improvement of teachers’ level, and vice versa (Haans et al., 2016; Mihalache et al., 2012).

In Equation (3), is the moderating variable curriculum development capacity, is the interaction term between curriculum development capacity and the integration level of industry and education; is the interaction term between curriculum development capacity and the square term of the integration level of industry and education. is the intercept term; denotes their estimated coefficients, where . is a random error term, and the meanings of other variables are consistent with those in Model (1). If , it means that the inflection point where the integration level of industry and education affects employment quality will move to the right with the improvement of teachers’ level, and vice versa.

Table 1 presents all variables and their definitions in this study.

Table 1.

Definitions of variables.

3.3. Entropy Method

As a widely used method in multi-index comprehensive evaluation, the entropy method determines the index weight by calculating information entropy. Its main advantage lies in effectively avoiding the interference of subjective factors, thereby enhancing the objectivity of the evaluation results. Accordingly, this study s adopts the entropy method to determine the weights of each index, and to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the index system. The specific calculation steps of the entropy method are as follows:

(1) Use the range difference method to standardize the original data to eliminate the influence of physical quantities.

where is the original value of the j-th index of the i-th college, represents the standardized index value, and and represent the maximum and minimum values of the index, respectively. To ensure that the standardized data retain operational significance, it is necessary to apply a translation, using 0.0001 as the translation constant.

(2) Calculate the proportion of the i-th college index value of the j-th index

(3) Entropy value; The formula for calculating the entropy value of the j-th index is:

(4) Difference coefficient; The formula for calculating the difference coefficient of the j-th index is:

(5) The weight of each evaluation index; The weight calculation formula of the j-th index is:

(6) Calculate the comprehensive level score of each college:

3.4. Variable Section and Definitions

Level of integration of industry and education (ie): Existing research mostly focuses on the connotation analysis of the integration of industry and education. Following Pan and Zhang (2024), we combine the core goal and essence of the integration of industry and education, and select seven indicators across five dimensions-curriculum co-construction, co-compilation of teaching materials, technology co-research, achievement sharing, and talent co-cultivation. Using an entropy weight method, we construct an evaluation index system for the level of industry-education integration (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Evaluation Index System for the Level of Industry-Education Integration.

These five dimensions and seven indicators are not only theoretically grounded but also reflect the key policy-oriented components emphasized in official guidance. For instance, the State Council’s Several Opinions on Deepening the Integration of Industry and Education (State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2017) explicitly highlights the importance of collaborative curriculum design, shared teaching resources, joint technology development, achievement sharing, and collaborative talent training. Similar dimensions are also advocated in studies such as Y. Wu et al. (2025) and Y. Li and Tian (2025), which argue that these aspects constitute the operational core of deep industry–education integration. The integration process typically begins with curriculum co-design, where educational institutions and enterprises jointly develop programs and syllabi to ensure alignment with industry standards and future skill requirements. This foundation enables the subsequent co-delivery of instruction, wherein industry experts participate in teaching activities and collaboratively develop pedagogical materials. Building on this educational framework, the process extends to technology co-research, in which both parties engage in joint research and development (R&D) projects, facilitating knowledge and innovation transfer. The integration further deepens through talent co-cultivation, implemented via structured programs such as dual-mentorship systems, internships, and apprenticeships, creating seamless pathways from education to employment. Ultimately, the process culminates in institutional co-governance, where partners establish shared platforms, jointly invest resources, and develop mechanisms for ongoing collaboration and quality assurance.

Throughout this process, collaborative curriculum development and co-authored teaching materials ensure that instructional content aligns with current industry standards and institutional academic requirements. Cooperative applied research and achievement sharing enhance the innovation value chain from R&D to production. Goal-oriented talent co-cultivation integrates educational and industrial resources to bridge skill gaps. Together, these practices form a comprehensive ecosystem that spans critical links across the education, talent, industry, and innovation chains, creating a virtuous cycle of mutual development that is consistent with the collaborative framework outlined in national policies.

Employment Quality (qhe). The implementation rate of employment destination is a direct indicator reflecting the employment number of graduates in higher vocational colleges (C. Chen & Zhou, 2017), and the salary competitiveness and development potential are important manifestations of graduates’ labor value and career growth kinetic energy. Following P. Yang et al. (2023), this paper selects three indicators: graduation destination implementation rate, monthly income, and promotion ratio three years after graduation, and uses the entropy weight method to comprehensively reflect the employment quality of graduates from higher vocational colleges (see Table 3 for details).

Table 3.

Evaluation Index System of Employment Quality.

This study selects teacher qualification and curriculum development capacity as the core moderating variables for two reasons. First, theoretical salience: under the resource-based view, faculty and curriculum are strategic, heterogeneous resources in higher vocational institutions and the primary channels through which external industry inputs are transformed into instructional advantages. Second, operational feasibility: both constructs are emphasized in national policy and are consistently reported in the Annual Report on Vocational Education Quality, providing reliable, comparable indicators for large-scale empirical measurement and policy evaluation.

Teacher Qualification Level (tql). Teachers’ professional titles are an important reflection of the comprehensive quality and ability of teachers in higher vocational colleges (Hou et al., 2024; Ying, 2025). Following C. Yang and Cen (2024), this study measures faculty quality by the proportion of full-time teachers holding senior professional and technical positions, defined as the ratio of full-time teachers with deputy senior titles or above to the total number of full-time faculty.

Curriculum Development Capacity (cdc). Curriculum construction closely focuses on the training objectives of vocational education to ensure the accurate connection between educational objectives and industrial needs. Following of Zhu et al. (2006), this paper selects five indexes, namely, including the number of college-enterprise cooperation courses, the number of class hours, the number of online quality courses, the number of class hours, and the number of students per course, and uses the entropy weight method to calculate.

The control variables contain: (1) dqt: Proportion of full-time teachers with “double-qualified” quality. This variable reflects the compound level of teachers’ theoretical and practical teaching ability (Zheng, 2022; S. Lu, 2022), and its level directly affects the matching degree between students’ vocational skills training and industrial demand. (2) nfm: Proportion of new form teaching materials. Reflecting the degree of integration of teaching content with digital technology and industrial frontier, the innovation and practicality of teaching materials may independently affect students’ knowledge structure and employment competitiveness (Dou, 2022) and need to be used as control variables to eliminate interference. (3) pjs: Number of practical teaching jobs per student on campus. It represents the adequacy of on-campus practical teaching resources. An insufficient number of jobs will limit the frequency of students’ practical training (Y. Chen & Zhang, 2025). This variable is complementary to the enterprise practice in the integration of industry and education and needs to be controlled to separate the impact of on-campus practice conditions on employment quality. (4) eqv: Value of teaching and scientific research instruments and equipment per student. Reflecting the support of hardware facilities in colleges and universities for technical skills cultivation (Xue & Mi, 2024), advanced equipment can improve students’ exposure to technology, and its input level may be independent of the integration of industry and education, affecting employment quality.

3.5. Data and Descriptive Statistics Summary

The data mainly comes from the “Annual Report on the Quality of Higher Vocational Education” (2024), released by various higher vocational universities and colleges2. After excluding the observations with missing values for key variables or incomplete reporting, the final sample includes 689 higher vocational institutions across 30 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions in mainland China (except Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, and Tibet). Missing data for some variables were filled through interpolation. A descriptive statistical summary for the main variables is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistical summary of variables.

Descriptive statistics for key variables are as follows. Employment quality (qhe) has a mean of 0.519 (SD = 0.232), ranging from 0.029 to 0.957, which indicate moderate variability across the sampled institutions. The level of industry-education integration (ie) averages 0.033 (SD = 0.043), ranging from 0 to 0.366, suggesting an overall low level of integration with significant variation between institutions. The proportion of full-time teachers with “double qualification” quality has a mean of 60.737 (SD = 21.634), spanning from 0.46 to 98.18, reflecting substantial disparities in faculty composition across colleges. The proportion of new-form teaching materials averages 0.267 (SD = 0.271), ranging from 0 to 1, showing that such materials account for a relatively small share on average, with notable institutional differences. The number of practical teaching positions per student on campus has a mean of 0.653 (SD = 0.395), ranging from 0 to 3.7. The value of teaching and scientific research instruments and equipment per student averages 13,194.580 (SD = 9965.411), ranging from ¥2312.680 to ¥86,667.640 (approximately $323.78–$12,133.47). These figures show significant cross-institutional variation in resource endowments.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

The multicollinearity test of the model was conducted to ensure the reliability of the statistical results. The test results show that the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of all variables is less than 10, indicating that multicollinearity is not a concern. All statistical results were performed using Stata 18.0 software.

Firstly, Table 5 presents the results of the benchmark regression model examining the impact of the integration level of industry and education on employment quality. In Table 5, Model (1) does not include control variables, but only pays attention to the nonlinear impact of the integration level of industry and education on employment quality. The estimated coefficient of the integration level of industry and education is 4.512, and its quadratic coefficient is −11.783, both of which are significant at the level of 1%. Furthermore, the control variables are incorporated into Model 1 to obtain Model 2. The results of Model 2 show that the coefficients of primary and quadratic terms of the integration level of industry and education are lower than those of Model 1, indicating that Model 1 overestimates its impact on employment quality. According to the results of Model 2, the coefficient of the first term of the integration level of industry and education is positive, and the coefficient of the quadratic term is negative, which indicates that the integration level of industry and education has a nonlinear “U”-shaped relationship with its employment quality, which is significant at the level of 1%. Employment quality reaches its maximum when the level of industry–education integration is 0.193. This may be explained by the fact that, in the early stage of industry–education integration, the connection between enterprise resources and educational resources substantially enhances the alignment between talent cultivation and market demand, thereby promoting improvements in employment quality. At this stage, the marginal return on resource input increases. However, as the scale of integration expands, the efficiency of resource allocation becomes constrained by the limited educational carrying capacity. Once the level of industry–education integration exceeds the critical threshold, marginal costs rise rapidly while marginal returns diminish, leading to a slowdown in employment quality improvements and eventually negative effects. On this basis, it has been confirmed that there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between industry-education integration and employment quality.

Table 5.

Baseline regression results: Impact of industry and education integration on employment quality.

4.2. Robustness Check

4.2.1. Inverted “U” Relationship Test

Since a significant quadratic coefficient alone is insufficient to confirm an (inverted) “U” relationship (Haans et al., 2016), the U test was applied to formally evaluate its presence. This test was used to confirm the inverted “U” relationship between the industry and education integration and employment quality, and the results are shown in Table 6. The results show that the interval of industry-education integration level is [0.000, 0.366], and the turning point is 0.157, indicating that the estimated value of the extreme point is within the value range of the independent variable data. The left interval has a slope of 3.709 and is significant at the 1% significance level, and the right interval has a slope of −4.943 and is significant at the 1% level. The results confirm an inverted “U” relationship between the integration level of industry and education, and employment quality, providing empirical support for Hypothesis 1.

Table 6.

Inverted “U” relationship test.

4.2.2. Other Robustness Tests

To avoid potential bias in the effect of industry–education integration on employment quality caused by sample selection or indicator choice, this study tested the robustness of the model by eliminating outliers, applying a 1% bilateral tailing treatment to all variables, and replacing the core explanatory variables. The results are reported in Table 7. Model 3 presents the regression results after tailing treatment. According to the regression results, the coefficients of the squared term of industry–education integration are all significant at the 1% level. Compared with the benchmark regression results, the direction of the coefficients remains unchanged, with only minor differences in magnitude, which further confirms the robustness of the findings. Model 4 reports the results obtained by replacing the measurement index of industry–education integration. As the core indicator of the collaborative allocation of human resources between colleges and enterprises, the number of industry tutors (nim) directly reflects both the depth and institutionalization of enterprise participation in the educational process. When the core explanatory variable is replaced with the number of industry tutors, the regression results on industry–education integration and employment quality remain stable.

Table 7.

Robustness check.

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Heterogeneity Effect Across Public and Private Colleges

Considering the differences between private colleges and public colleges in terms of funding sources, governance mechanisms, policy constraints, etc., the level of integration of industry and education has different effects on employment quality. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the heterogeneity associated with the nature of colleges and universities. Based on this, the research sample is divided into two groups—private and public institutions—according to their institutional nature, and the corresponding empirical results are reported. According to the results in Table 8, in the short term, private colleges and universities (Model 6) exhibit a greater effect on employment quality through industry–education integration than public colleges and universities (Model 7). However, as the level of integration deepens, the inflection point for private colleges and universities occurs much earlier than for public ones, and once this threshold is exceeded, the employment quality in private colleges declines much rapidly than in public colleges and universities.

Table 8.

Heterogeneity Test Results.

First, public colleges and universities face rigid constraints, as the industry–education integration projects require multiple layers of approval, resulting in slower responses. By contrast, private colleges and universities enjoy greater autonomy in contract pricing and income distribution, enabling them to respond quickly to meet the market demand and achieve favorable employment outcomes in the short term. Second, the funds of private colleges and universities primarily depend on tuition revenue and social capital investment. Because social capital is highly profit- driven, if the industry-education integration project fails to deliver the expected returns in the short term, the capital investment is likely to be discontinued. In contrast, with more secure funding sources, public colleges and universities are able to sustain resource investment, maintain in advancing integration, and postpone the inflection points even when the short-term returns from industry-education integration projects are limited. Finally, public colleges and universities shoulder multiple missions, including talent, social services and cultural inheritance. The objective of industry–education integration is not limited to improving employment quality, but also extends to supporting industrial upgrading and technological innovation. This diversified mission encourages public institutions to emphasize the development of students’ comprehensive ability within the integration process. As a result, and even when the job market fluctuates in the short term, they are able to maintain the employment quality by adjusting the training directions. In contrast, the private colleges and universities place greater emphasis on immediate feedback from the job market. When the alignment between talent output and enterprise demand declines due to industrial upgrading, employment quality at private institutions deteriorates rapidly, owing to the absence of multiple buffering objectives. In pursuit of short-term employment outcomes, subsequent adjustments in integration are more likely to become reactive, accelerating the arrival of the inflection point and deepening the decline in employment quality.

4.3.2. Heterogeneity Effects Between “Double High” and Non-“Double High” Colleges

In 2019, the State Council proposed the construction plan of high-level higher vocational colleges and majors with Chinese characteristics (the “Double High Plan”3), which guides vocational education to serve national strategies, integrate into regional development, and promote industrial upgrading. Significant differences exist between “double-high” colleges and non-“double-high” colleges in their development. To further examine how industry–education integration affects employment quality across these institutional types, the research sample is divided into “double-high” and non-“double-high” colleges, with regression results presented in Table 8.

According to the results, the initial integration effect of non-“double-high” colleges is greater than that of “double-high” colleges, reflecting that the limited scope for marginal improvement in “Double High” colleges due to their strong original foundation. In the long run, the inflection point for “double-high” colleges occurs earlier than that of non-“double-high” colleges, indicating that they experience diminishing returns sooner. the post-inflection decline rate in employment quality is similar for both types of institutions, the actual employment quality of “double-high” colleges and universities remains higher because of their superior starting point. This may be attributed to the influence of policy-driven assessment orientations, which can foster a path dependence of “emphasizing innovation while neglecting practicality.” For example, in order to produce “landmark results,” many “Double High” colleges allocate resources to the research and development of advanced training equipment. While this enhances their institutional reputation, the skills developed may not directly align with students’ actual employment positions, resulting in only limited improvements in initial employment quality. By contrast, non-“Double High” colleges adopt a more practical orientation, with integration measures directly targeting the job needs of local enterprises, thereby generating faster employment effects. In the long run, the accumulation of innovation in “Double High” colleges gradually translates into employment advantages. However, the inherent trial-and-error nature of innovation causes them to encounter diminishing returns earlier: once model innovation reaches industry boundaries, the employment returns on new investments decline rapidly. Conversely, the inflection point of diminishing returns appears later for non-“Double High” colleges, owing to their more “practical and steady progress” approach.

4.4. Results of the Moderating Effect

4.4.1. Results of the Moderating Effect of Teacher Qualification Level

To further verify the adjustment effect of teachers’ qualification level on the employment quality within the context of industry–education integration, the interaction term between teachers’ qualification levels and the integration level of industry and education and the interaction term between teachers’ qualification levels and the square term of the integration level of industry and education, were constructed for regression, and the results are shown in the Model 9 of Table 9. According to the results, the estimated coefficient of the interaction term between the teachers’ qualification level and the square term of the integration level of industry and education is significantly positive at the level of 10%, with a coefficient of 0.371. This indicates that the teachers’ qualification level regulates the relationship between industry–education integration and employment quality. As = 0.63 > 0, the inflection point shifts to the right, indicating that the improvement of teachers’ qualification level weakens the positive effect before the inflection point and the negative effect after the inflection point of the inverted U-shaped curve. In the early stage of the integration of industry and education, although high-level teachers can improve the quality of employment by strengthening the alignment of teaching practice, their promotion effect diminishes marginally due to the scale and depth of college-enterprise cooperation. When the level of integration exceeds the critical point, problems such as goal divergence and resource misallocation caused by over-integration intensify. At this stage, high-level teachers, relying on their industry insight and ability to transform technology, can effectively alleviate the negative impact caused by over-integration by reconstructing teaching content, innovating teaching mode, and building communication bridges, thereby slowing the decline on the right side of the inverted U-shaped curve and shifting the inflection point to the right. Based on this, it has been confirmed that the level of teacher qualifications exerts a negative moderating effect on the inverted U-shaped relationship between the two.

Table 9.

Test results of the moderating effect.

4.4.2. The Moderating Effect of Curriculum Development Capacity

To further verify the moderating effect of curriculum development capacity on the employment quality within industry–education integration, the interaction terms between the integration level of industry and education, its square term, and curriculum development capacity were constructed for regression, and the results are shown in Model 10 in Table 9. According to the results, the estimated coefficient of the interaction term between curriculum development capacity and the square term of industry–education integration is significantly positive at the 1% significance level, which indicates that curriculum development capacity has a significant moderating effect on the employment quality within industry–education integration. As = 21.19 > 0, the inflection point shifts to the right, meaning that the improvement of curriculum development capacity weakens the positive effect before the inflection point and the negative effect after the inflection point of the “U” curve. When the industry–education integration is at a low level, although the improvement of curriculum development capacity can strengthen employment quality by optimizing teaching content and adding practical modules, its marginal contribution is gradually weakened due to the carrying capacity of the curriculum system; When industry–education integration exceeds the critical value and enters the right side of the inverted “U” curve, excessive college-enterprise cooperation can easily lead to problems such as redundant curriculum content and vague training objectives. At this stage, the improvement of curriculum development capacity can restrain the downward trend of employment quality caused by over-integration by continuously optimizing the curriculum structure, updating teaching content, strengthening practice components, etc. This mitigates the negative effect on the right side of the inverted “U” curve, shift the inflection point the right, flattens the overall curve, thereby ensuring the adjustment and protection of employment quality. Based on this, it has been confirmed that curriculum development capacity exerts a negative moderating effect on the inverted U-shaped relationship between the two.

5. Discussion

This study identifies an inverted U-shaped relationship between the level of industry-education integration and employment quality, with teacher qualification level and curriculum development capacity serving as negative moderating variables. The findings possess a degree of generalizability across national vocational education systems. For instance, Germany’s dual-system vocational training emphasizes deep enterprise involvement in the educational process, the success of which relies on stable policy support and standardized industry-oriented curricula. Similarly, U.S. community colleges promote employment quality through flexible alignment with local industry needs and continuous teacher development. These international experiences suggest that the appropriate intensity and structural safeguards of industry-education integration are common critical factors in enhancing employment quality. Nonetheless, the generalization of these findings should account for differences in national policy systems, industrial structures, and educational traditions. In government-led vocational education systems, strong policy intervention and resource allocation capabilities facilitate the implementation of integration optimization mechanisms; in market-led systems, greater reliance is placed on industry associations and self-organizing school–enterprise collaboration. Future research could incorporate cross-national comparisons and additional variables related to cultural context and institutional environment to clarify the boundary conditions under which the industry-education integration is effective and to yield more generalizable insights for vocational education policies.

Furthermore, this study only considers institutional “teaching-side” capabilities and does not include variables such as industry-representative teaching capacity on the enterprise side and individual absorptive capacity—e.g., as students’ critical thinking—on the student side. The former affects the efficiency of knowledge transfer between schools and enterprises, while the latter influences students’ integration of practical skills with theory. This limited set of moderating variables may result in an incomplete interpretation of the underlying mechanisms, suggesting that future studies could expand the range of moderators examined.

Finally, the data used in this study lack timeliness and a dynamic perspective. Because the analysis relies solely on single-year (2024) cross-sectional data, it cannot capture long-term dynamics in the relationship between industry-education integration and employment quality. It also prevents assessing the temporal stability of moderating effects, potentially constraining the evaluation of integration effects. Subsequent research should incorporate multi-period panel data and longer time-series observations to trace the evolution of industry-education integration and employment quality, thereby extending the temporal dimension and enabling a more dynamic analytical framework.

6. Conclusions and Implications

Based on the cross-sectional data from 689 higher vocational colleges in China in 2024, this paper constructs a nonlinear model and a moderating effect model to explore the impact of the level of industry-education integration on employment quality. The results show that the level of integration of industry and education has a significant inverted “U” relationship with employment quality: it first promotes and then suppresses it. When the level of integration of industry and education exceeds the critical value of 0.193, the employment quality turns into a negative effect. Second, teachers’ level and curriculum development capacity can weaken the inverted “U” relationship between the integration level of industry and education and employment quality, shifting the inflection point to the right. Finally, the impact of the integration level of industry and education on employment quality is heterogeneous with respect to college type and “Double High” status. In the early stage, private colleges and universities exhibit a significantly stronger positive effect on employment quality than public colleges and universities, but the inflection point of integration occurs earlier, and employment quality declines more rapidly after the inflection point. The initial effect of industry–education integration in “double-high” colleges is lower than that in non-“double-high” colleges, and the inflection point occurs earlier, but the actual employment quality remains higher due to their stronger foundation.

To enhance the employment quality of students in higher vocational colleges, the following countermeasures and suggestions are proposed according to the above conclusions.

First, build an optimization mechanism for the integration of industry and education to avoid the trap of “over-integration”. On the one hand, establish a dynamic monitoring and evaluation system, and take the achievement of educational goals, the alignment with industrial needs, and the sustainability of student development as the core indicators to evaluate the entire process of industry-education integration projects. By regularly analyzing the integration data, potential problems can be identified in a timely manner, preventing the excessive intrusion of industrial demand into the education system. On the other hand, the governance structure of multi-party participation should be improved to form a decision-making and coordination mechanism in which the government, enterprises, colleges, trade associations, and other stakeholders. According to their respective responsibilities and advantages, each stakeholder should play a defined role in the formulation of talent training programs, curriculum development, practical teaching, and other aspects. This not only ensures the effective incorporation of industrial demand, but also preserves the educational mission of higher education, thereby promoting the healthy development of industry–education integration.

Second, strengthen teachers’ practical teaching ability and the development of curriculum adaptability. As the key implementers of the integration of industry and education, teachers’ practical teaching ability directly affects the outcomes of talent training. To strengthen teachers’ practical teaching ability, it is necessary to build a training model that combines “bringing in” and “going out”. On the one hand, actively introduce professionals with rich practical experience in the industry as part-time teachers, to enrich the faculty, and bring cutting-edge knowledge and practical cases in the industry into the classroom. On the other hand, establish a system of enterprise-based practice, encourage in-service teachers to regularly engage with enterprises, participate in actual project research and development, industry and operation, accumulate practical experience, and update their knowledge base. In terms of curriculum adaptability, the curriculum content and structure are dynamically adjusted according to the industrial demand. By jointly developing courses with enterprises, new technologies, standards, and processes are integrated into teaching, thereby enhancing course practicality and timeliness. At the same time, we should pay attention to the modular and flexible design of courses, allowing curriculum modules to be combined according to different professional orientations and students’ needs, thus cultivating students’ comprehensive practical abilities and professional competencies.

Third, implement differentiated guidance and support policies to effectively enhance employment quality. In view of the heterogeneous characteristics of higher vocational colleges in the integration of industry and education and employment quality improvement, policy design needs to address both common needs and individual differences. It is recommended to establish a policy support system of “hierarchical classification-dynamic adjustment”. On the one hand, through inclusive policies such as tax relief and special funds, all higher vocational colleges should be encouraged to establish long-term cooperative relations with enterprises, while enterprises should be supported in participating in core areas such as curriculum development and training base construction. On the other hand, the quality evaluation standards of the integration of industry and education should be established, and the weight of resource allocation should be dynamically adjusted according to the type and development stage of colleges and universities. For example, the supervision of processes in colleges and universities that have achieved remarkable results in the initial stage of the integration of industry and education should be strengthened, and the funding and resource preference should be increased for colleges and universities that lag behind in development. At the same time, a regional platform for integrating and sharing industry–education resources, promoting, promoting the exchange of resources between “double-high” colleges and non-“double-high” colleges, as well as between public and private colleges in terms of teachers, technology and projects, to form a pattern of complementary advantages and coordinated development, so as to finally achieve an overall improvement in the employment quality of higher vocational colleges.

Author Contributions

Y.C. was responsible for Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing-review and editing; S.L. was responsible for Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing-review and editing, and Funding acquisition; R.C. was responsible for Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing-review and editing, Supervision, and Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the USDA NIFA, Evan Alan program (Project No. ALX-SRS22/Project Accession No. 7004055), the USDA-NIFA Rural Economic Development program (Award No. 2023-69006-40213), and the USDA-NIFA SAS project (Award No. 2023-68012-38994). This research was also supported by the 2024 Hebei Provincial Research and Practice Project on Vocational Education Teaching Reform—“Study on the Coupling between New-Quality Productive Forces and High-Quality Development of Vocational Education in Hebei Province” (Project No.: 2024ZJJGGA14). We are also grateful for support from the University Cooperative Extension Program, College of Agriculture, Environment and Nutrition Sciences, and George Washington Carver Agricultural Experiment Station.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All authors agreed not to share data for the time being.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The “Order Class” initiative: First proposed by China’s Ministry of Education in the Opinions on Deepening Comprehensive Education Reform (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, 2013), this employment-oriented talent-training model is a cohort-based, industry–academia training program jointly designed by a partner enterprise and a vocational college to meet actual job requirements (J. Huang et al., 2018). Typically, enterprises co-develop the curricula, provide practical training equipment, and may dispatch technical backbone personnel as instructors. In turn, vocational institutions deliver targeted instruction and require students to complete both theoretical learning and enterprise-based practice; some receive enterprise scholarships or directed internships. Graduates who meet the enterprise’s hiring criteria are typically hired directly, realizing “a confirmed position upon enrollment and employment upon graduation.” This model can strengthen the linkage between vocational education and industry needs. |

| 2 | In this paper, vocational education includes both vocational colleges and vocational universities. While both follow an industry demand-driven logic of industry–education integration, their emphases differ: vocational colleges prioritize foundational skill adaptation via more direct, standardized integration pathways suited to front-line operational roles (S. Li & Zhang, 2022); vocational universities emphasize advanced competency enhancement, adopting more systematic, project-based integration to prepare students for complex technical applications and entry-level management responsibilities (S. Gao & Li, 2025). Our study includes a total of 689 institutions, comprising 664 vocational colleges and 25 vocational universities. We did not separate “vocational universities” from “vocational colleges” because the 25 universities were upgraded only 2–3 years ago and, during the study period, had not yet produced graduates from advanced industry–education integration programs; that is, data on such programs were unavailable (only standard-program data were available), indicating no substantive operational divergence. |

| 3 | “Double High Plan”: a national initiative launched in 2019 by China’s Ministry of Education and Ministry of Finance to build high-level higher-vocational institutions and majors. Implemented in five-year cycles, it aims to develop ~50 leading higher-vocational colleges and ~150 high-level specialty clusters, establishing “highlands” for skilled-talent cultivation and innovation and fostering dual-qualified teaching teams (C. Wang, 2025). Widely regarded as the vocational-education counterpart to the “Double First-Class” initiative in higher education, the plan advances vocational-education reform, supports industrial upgrading, and strengthens the sector’s capacity to serve economic and social development. |

References

- Chai, M. (2020). Research on the school-enterprise cooperation in the background of the industry-education integration. Theory and Practice of Education, 40(3), 3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C., & Zhou, L. (2017). An empirical study on the influencing factors of employment quality of hotel management majors in higher vocational colleges. Journal of Vocational Education, (20), 5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. (2021). Talent training mode of order class in higher vocational colleges under the background of industry-education integration. Education and Vocation, 46(2), 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., & Zhang, L. (2025). Does the construction of demonstrative industry colleges improve the level of specialty setting and industrial adaptability in higher vocational colleges?—Empirical study based on the difference-in-difference model. Vocational and Technical Education, 46(10), 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, F. (2022). “Integrated curriculum, practical training, competitions, and certificates”—The development logic and pathway of new forms of vocational education textbooks. China Vocational Education, (26), 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X. (2023). Exploration of high quality employment path based on the integration of industry and education: Taking the logistics management major of sichuan vocational and technical college of communications as an example. Transportation Enterprise Management, 38(5), 95–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F., & Zhang, P. (2020). Performance evaluation of industry-education integration in higher vocational colleges: An evidence from China. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 15(23), 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S., & Li, J. (2025). Deepen comprehensive classification reform in higher education to systematically enhance the ability to cultivate applied and skilled talents. Chinese Vocational and Technical Education, (16), 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Glavina, A., Mišić, K., Baleta, J., Wang, J., & Mikulčić, H. (2025). Economic development and climate change: Achieving a sustainable balance. Cleaner Engineering and Technology, 26, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W. (2023). Analysis on the training model of “integration of industry and education with dual education mode” for composite talents in mechanical and electrical engineering in higher vocational education. International Journal of Mathematics and Systems Science, 6(3). [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X. (2024). Performance evaluation of industry-education integration in higher education from the perspective of coupling coordination-an empirical study based on Chongqing. PLoS ONE, 19(9), e0308572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haans, R. F. J., Pieters, C., & He, Z. L. (2016). Thinking about U: Theorizing and testing U-- and inverted U--shaped relationships in strategy research. Strategic Management Journal, 37(7), 1177–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H., & Huang, Z. (2025, July 23–25). Research and practice on the construction of intelligent equipment practice center with industry-education integration under the background of “double high-levels plan”. 2025 6th International Conference on Economics, Education and Social Research, Okinawa, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y., Zhang, Y., & Luo, X. (2024). How do teacher resources in higher vocational colleges affect graduates’ employment?—An empirical study based on the annual data of education quality of 1090 higher vocational colleges. Tsinghua Journal of Education, 45(6), 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y., Wang, Y., & Jiang, N. (2022). Analysis of the path to quality employment for students in higher vocational colleges under the context of high-quality development. Chinese Vocational and Technical Education, (31), 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D., & Du, W. (2019). Research on the construction of production-oriented training centers within higher vocational colleges based on industry-education integration. Chinese Vocational and Technical Education, (2), 5. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J., Zhu, X., & Huang, X. (2018). Standardized construction of order training in higher vocational education—The case of subway operation industry. Vocational and Technical Education, 39(14), 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M., Su, X., & Chao, T. (2025). Research on the teaching problems and strategies of data journalism courses in local universities under the background of industry-education integration. Education Journal, 8(6). [Google Scholar]

- Lei, W. (2022). On Practical dilemma and solution of industry-education integration from perspective of organizational cooperation. Research in Higher Education of Engineering, 70(1), 104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S., & Zhang, X. (2022). The orientation of specialized education under the background of modern vocational education system: Survival value, logical basis and practical scheme. Chinese Vocational and Technical Education, (9), 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T. (2025). Research on the construction of practical teaching system for logistics management based on the enhancement of employment competitiveness. Probe-Environmental Science and Technology, 7(2). [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., & Tian, Z. (2025). Measuring collaboration of industry and TVET from the perspective of data governance: Theoretical logic and practical exploration. Education & Economy, 41(3), 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L., & Deng, J. (2021). Problems and countermeasures of the construction of “double-qualified” teachers in higher vocational colleges from the perspective of industry-education integration. Vocational and Technical Education, 42(26), 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S. (2022, April 14–15). Construction of “dual-qualified” teachers in higher vocational colleges from the perspective of the integration of industry and education. The Second International Education Conference: Current Issues and Digital Technology (ICECIDT 2022), Online. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C., & Li, J. (2025). Theoretical construction and empirical test of U-shaped relationships in management research. Journal of Technology Economicsi, (5), 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L., Ma, J., & Zhang, W. (2025). Talent development pathways for innovation and entrepreneurship in university-industry collaboration. Research in Higher Education of Engineering, (S1), 177–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S., & Guo, W. (2018). Experiences, problems and countermeasures in deepening industry-university integration of technical and vocational higher education. China Higher Education Research, 4, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalache, O. R., Jansen, J. J. J. P., Bosch, F. A. J. V. D., & Volberda, H. W. (2012). Offshoring and firm innovation: The moderating role of top management team attributes. Strategic Management Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education, National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security & State Taxation Administration. (2018). Notice on issuing the provisions on enterprise practice for teachers in vocational schools (Teacher [2016] No. 3). Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A10/s7011/201605/t20160530_246885.html (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2013). Opinions of the ministry of education on deepening comprehensive reform in the field of education in 2013 [Jiaogai (2013) No. 1]. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A27/zhggs_other/201301/t20130129_148072.html (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Miu, C. (2023). An empirical analysis of the supply and demand matching of vocational education technical skills talents in skill-based social construction. Education and Vocational, (17), 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H., & Zhang, X. (2024). Study on measuring the development level of industry-education integration in provincial vocational education. Modern Education Management, 12, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J., Wu, Q., Han, Z., Gong, K., & Wang, D. (2018). Research on the education of industry-education integration for geological majors. Kuram ve Uygulamada Egitim Bilimleri, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W., & Hao, T. (2025). Vocational education system with industry-education integration: Logical dimensions, essential connotations, and construction strategies. Journal of Vocational Education, 41(8), 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2017). Opinions of the general office of the state council on deepening the integration of industry and education. [Guobanfa (2017) No. 95]. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-12/19/content_5248564.htm (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Sun, X. (2023). Strategies for Enhancing high-quality employment of architecture majors in the context of industry-academia integration. Building Structure, (8). [Google Scholar]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2024). Report on the work of the government [R/OL].

- Wan, B. (2019). Problems and paths of higher vocational school-enterprise cooperation under the background of industry-education integration. Education and Vocation, (15), 7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. (2025). The experience and prospect of the construction of national “double high plan” under the background of building an education power. Chinese Vocational and Technical Education, 1, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D., & Zhao, P. (2014). Exploration of collaborative education mechanism in higher vocational colleges from the perspective of industry-academia integration. China Higher Education, 21, 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. (2020). Research on countermeasures for vocational education specialty construction under background of integration of industry and education—Based on Investigation of current situation of integration of industry and education of 40 vocational colleges in Beijing. Vocational and Technical Education, 41(33), 8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L., Zhao, L., & Liu, Z. (2025). Exploration of teaching model reform for marketing major courses in the background of industry-education integration: A case study of the brand planning workshop course. Region-Educational Research and Reviews, 7(4). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., & Dong, Y. (2024). Implication and practical ways of the times of high-quality and full employment of higher vocational graduates from the perspective of “double-high plan”. Vocational and Technical Education, 45(8), 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. (2021). The impact of feed enterprises on the development of higher vocational students’ entrepreneurship and employment from the perspective of industry education integration. China Feed, 4, 136–139. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y., Xu, S., Bai, Y., Shen, J., & Tang, R. (2025). Evaluating industry-academia collaboration: Theories, principles and frameworks. Modern University Education, 41(4), 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z. (2021). Research on strategies for cultivating students’ innovation and entrepreneurship abilities in higher vocational colleges based on industry-academia integration. Survey of Education, 10(14), 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S. (2020). Analysis on the Path to Improve the Employability of Higher Vocational Students under the Background of Industry-Education Integration. Journal of Jining Normal University, 42(6), 101–104+119. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y., Huang, Y., Li, J., Lai, H., & Qiu, Y. (2019). Fusion and innovation, effectively improve the quality of “golden course”. China Educational Technology, (11), 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F. (2011). Research on the employment situation and countermeasures of graduates from the physical education major of Suzhou vocational university. Science & Technology Information, 30, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. (2025). Research on the construction path of university innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystem under the background of industry-education integration. Journal of Frontier Disciplines Research, 2(2), 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, L., & Mi, J. (2024). Research on the countermeasures of vocational education to improve the demographic dividend from the perspective of demographic transition. Chinese Vocational and Technical Education, (15), 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L. (2025). The path to improve the quality and efficiency of innovation and entrepreneurship education in colleges and universities under the perspective of college students employment. Journal of Higher Education Research, 6(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B., & Dai, F. (2018). Research on effective paths for cultivating core competencies of higher vocational students from the perspective of industry-academia integration. Science &Technology Economic Market, (11), 2. [Google Scholar]