Learning Through Cooperation in the Activities of 1st-Grade Pupils (7 Years Old) Using the Lesson Study Methodology: The Case of One Lithuanian School

Abstract

1. Introduction

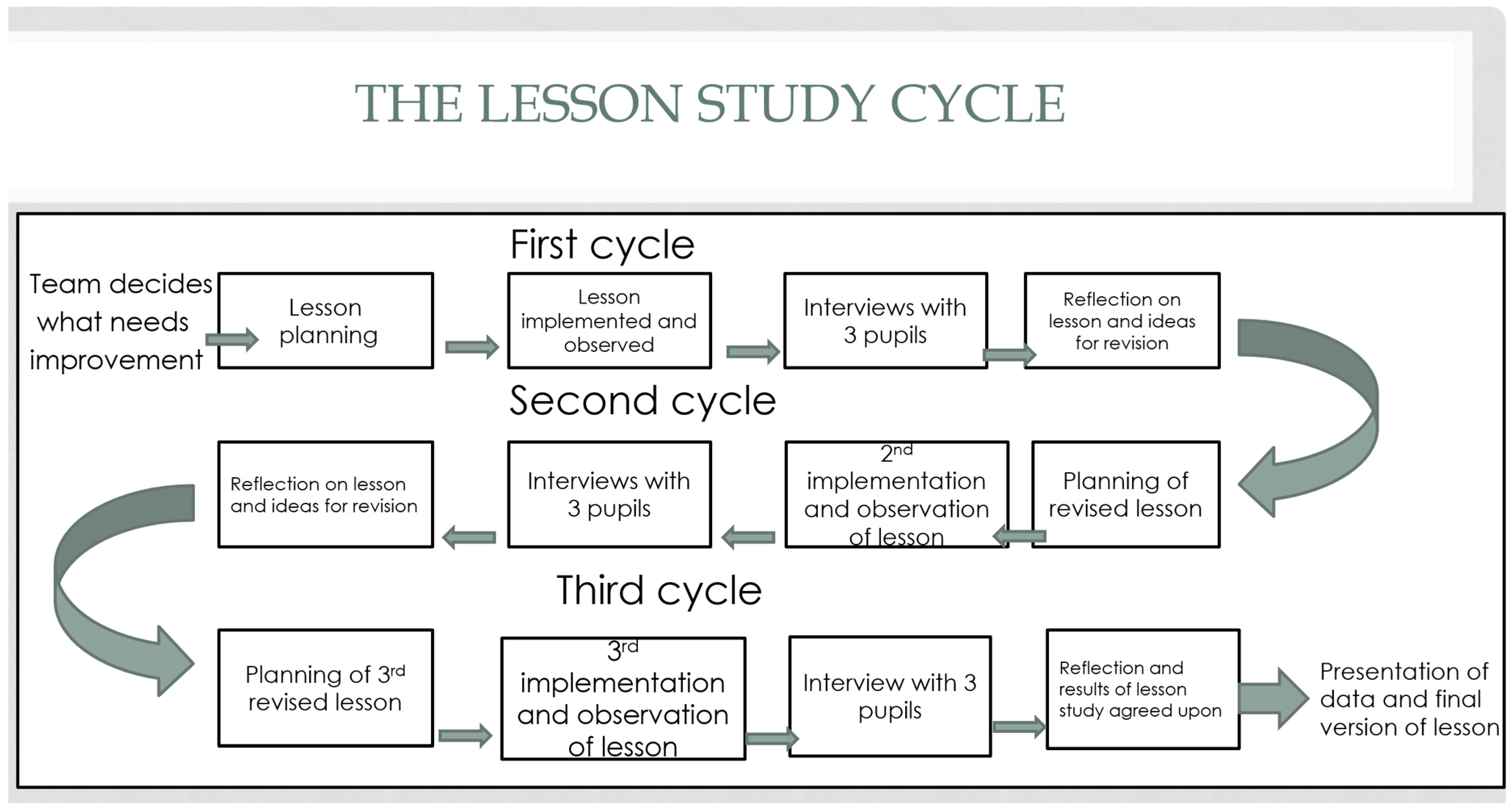

2. Lesson Study Methodology

2.1. Teacher Cooperation as a Prerequisite for the Implementation of the Lesson Study Methodology

2.2. Methods of Data Collection and Analysis

2.3. Research Questions

- -

- Positive interdependence and interaction;

- -

- Individual responsibility and cooperation;

- -

- Group performance evaluation.

3. Analysis of the Empirical Study Data

3.1. Teachers Noticed Positive Interdependence and Interaction Among Pupils in Class

3.2. Teachers Noticed Individual Responsibility and Cooperation Among Pupils in Class

3.3. Teachers Noticed of Pupils Group Work Assessment in Class

4. Discussion and Conclusions

5. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrami, P.-C., Chambers, B., Poulsen, C., D’Apollonia, S., & Howden, J. (1995). Classroom connections: Understanding and using cooperative learning. Harcourt-Brace. [Google Scholar]

- Akiba, M., Murata, A., Howard, C. C., & Wilkinson, B. (2019). Lesson study design features for supporting collaborative teacher learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkari, A., & Radhouane, M. (2020). Au-delà du débat conceptuel multiculturalisme ou interculturalisme: Comment libérer le potentiel de la diversité culturelle en éducation [Beyond the conceptual debate of multiculturalism vs. Interculturalism: How to unleash the potential of cultural diversity in education]? Ecolint Institute Research Journal, 6, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Alansari, M., & Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2021). Enablers and barriers to successful implementation of cooperative learning through professional development. Education Sciences, 11(7), 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, R. (2020). A dialogic teaching companion (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D. L., & Forzani, F. M. (2009). The work of teaching and the challenge for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(5), 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjuland, R., & Mosvold, R. (2015). Lesson study in teacher education: Learning from a challengingcase. Teaching and Teacher Education, 52, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, J., & Dugas, N. (2002). La reconnaissance au travail: Une pratique riche de sens; document de sensibilisation [Recognition at work: A meaning-rich practice; an awareness-raising document]. Centre D’expertise en Gestion des Ressources Humaines. [Google Scholar]

- Brun, J., & Dugas, N. (2005). La reconnaissance au travail: Analyse d’un concept riche de sens [Recognition at work: Analysis of a meaning-rich concept]. Gestion, 2(2), 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budex, C. (2020). Éduquer à la fraternité par la pratique de la philosophie à l’école (primaire et collège): Enjeux et conditions de possibilités [Educating for fraternity through the practice of philosophy in (primary and middle) schools: Stakes and conditions of possibility] [Thèse de doctorat inédite en Sciences de l’éducation et de la formation, Université de Nantes, France]. [Google Scholar]

- Cifali, M. (2022). Avons-nous vraiment besoin de ce mot [Do we really need this word]? Cahiers Pédagogiques, 575, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Connac, S. (2020). La coopération, ça s’apprend [Cooperation is something that can be learned]. ESF Sciences Humaines. [Google Scholar]

- Connac, S. (2021). Pour différencier: Individualiser ou personnaliser [To differentiate: To individualize or to personalize]? Education et Socialisation, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connac, S. (2022). Coopérer ou collaborer, est-ce la même chose [Cooperate or collaborate: Is it the same thing]? Cahiers Pédagogiques, 576, 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connac, S., & Irigoyen, A. (2023). Apprentissage coopératif ou pedagogies coopératives [Cooperative learning or cooperative pedagogies]? Éducation et Socialisation, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connac, S., & Rusu, C. (2021). Analyse de l’activité de lycéens en situations pédagogiques de travail en groupe [Analysis of High School Students’ Activity in Pedagogical Group Work Situations]. Activités, 18(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, W., Bishaw, A., & Dagnew, A. (2018). Preservice teachers’ approaches to learning and their teaching approach preferences: Secondary teacher education program in focus. Cogent Education, 5, 1502396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, S., Roorda, G., & Van Veen, K. (2017). Lesson study: Effectief en bruikbaar in het Nederlandse onderwijs? [Lesson study: Effective and practicable in the Dutch context?]. Geraadpleegd op 7-11-2022 van. Available online: www.nro.nl/kb/405-15-726 (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Dudley, P. (2013). Teacher learning in Lesson Study: What interaction-level discourse analysis revealed about how teachers utilised imagination, tacit knowledge of teaching and fresh evidence of pupils learning, to develop practice knowledge and so enhance their pupils’ learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 34, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbilgin, E., & Robinson, J. M. (2025). A reflective account of facilitating teachers’ professional learning in two different lesson study settings. Education Sciences, 15(1), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernagu-Oudet, S. (2018). Organisation et apprentissage: Des compétences aux capabilités [Organization and learning: From competencies to capabilities] [Doctoral dissertation, Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté]. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, T. (2014). Implementing Japanese lesson study in foreign countries: Misconceptions revealed. Mathematics Teacher Education and Development, 16(1), 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gillies, R.-M. (2014). Developments in cooperative learning: Review of research. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 30(3), 792–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, N. (2013). Approche coopérative et complexe en éducation [Cooperative and complex approach in education]. In M. Sumputh, & F. Fourcade (Eds.), Oser la pédagogie coopérative complexe (pp. 47–80). Chronique Sociale. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, S., Doig, B., Vale, C., & Widjaja, W. (2016). Critical factors in the adaptation and implementation of Japanese lesson study in the Australian context. ZDM, 48, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håland, A., Wagner, Å. K. H., & McTigue, E. M. (2021). How do Norwegian second-grade teachers use guided reading? The quantity and quality of practices. L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 21, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honneth, A. (2004). La théorie de la reconnaissance: Une esquisse [The theory of recognition: A sketch]. Revue du MAUSS, 1(1), 133136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honneth, A. (2013). La lutte pour la reconnaissance [The Struggle for Recognition] (P. Rusch, Trans.). Gallimard collection folio essais, (no. 576), Folio essais. CERF. (Ouvrage original publié en 2000). [Google Scholar]

- Hortigüela-Alcalá, D., Hernando-Garijo, A., González-Víllora, S., Pastor-Vicedo, J. C., & Baena-Extremera, A. (2020). “Cooperative learning does not work for me”: Analysis of its implementation in future physical education teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourigan, M., & Leavy, A. M. (2023). Elementary teachers’ experience of engaging with teaching through problem solving using lesson study. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 35, 901–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacq, C., & Ria, L. (2019). Penser l’apprentissage en situation de travail en contexte scolaire: Vers des circonscriptions, des établissements formateurs et apprenants [Rethinking work-based learning in the school context: Towards learning and training-oriented districts and institutions]. Administration & Éducation, 1(161), 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakavonytė-Staškuvienė, D. (2021). The benefits of cooperative learning of language in different subject lessons as seen by primary school pupils: The case of one Lithuanian city school. Education Research International, 2021(1), 6441222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakavonytė-Staškuvienė, D., Žemgulienė, A., & Sakadolskis, E.-A. (2021). Cooperative learning issues in elementary education: A Lithuanian case study. Journal of Education Culture and Society, 12(1), 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, S., Knippels, M.-C. P. J., & van Joolingen, W. R. (2021). Lesson study as a research approach: A case study. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies, 10(3), 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.-W., & Johnson, R.-T. (2015). Theorical approaches to cooperative learning. In R. M. Gillies (Ed.), Collaborative learning: Developments in research and practice (pp. 17–46). Nova Science. [Google Scholar]

- Kanellopoulou, E.-M. D., & Darra, M. (2019). Benefits, difficulties and conditions of lesson study implementation in basic teacher education: A review. International Journal of Higher Education, 8(4), 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafontaine, L., Dumais, C., & Pharand, J. (2016). L’oral au 1er cycle de l’école primaire québécoise: Assises théoriques et démarche d’enseignement et d’évaluation [Oral skills in the first cycle of quebec primary school: Theoretical foundations and a approach to teaching and assessment]. Repères Recherches en Didactique du Français Langue Maternelle, 54, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L. H. J., & Tan, S. C. (2020). Teacher learning in lesson study: Affordances, disturbances, contradictions, and implications. Teaching and Teacher Education, 89, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithuanian General Programmes for Primary Education. (2022). Lietuvos pradinio ugdymo bendrosios programos. Nacionalinė švietimo agentūra. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, V., Mata, L., & Nóbrega Santos, N. (2021). Assessment conceptions and practices: Perspectives of primary school teachers and students. Frontiers in Education, 6, 631185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numa Bocage, L. (2020). L’entretien d’analyse de l’activité en didactique professionnelle: L’EACDP [The activity analysis interview in professional didactics: The EACDP]. Phronesis, 9, 37–48. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-04109229/ (accessed on 5 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2016). Résultats du PISA 2015: Politiques et pratiques pour des établissements performants [Results from PISA 2015: Policies and Practices for Successful Schools] (Vol. 2). PISA, Éditions OCDE. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2020). PISA 2018 results: Effective policies, successful schools (Vol. V). PISA, Éditions OCDE. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2021). Students’ socio-economic status and performance (Chapter 2). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/student-socio-economic-status.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Order of the Minister of Education, Science and Sport of the Republic of Lithuania. (2023). m. rugpjūčio 31 d. Nr. V-1125. Lietuvos Respublikos švietimo, mokslo ir sporto ministro įsakymas. Mokinių, kurie mokosi pagal bendrojo ugdymo programas, mokymosi pasiekimų vertinimo ir vertinimo rezultatų panaudojimo tvarkos aprašas. Švietimo, mokslo ir sporto ministerija. Available online: https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/e536295047ec11ee9de9e7e0fd363afc (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Paillé, P., & Mucchielli, A. (2003). L’analyse qualitative en sciences humaines et sociales [Qualitative analysis in the humanities and social sciences]. Armand Colin. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paternotte, C. (2017). Agir ensemble—Fondements de la coopération [Acting together—Foundations of cooperation]. Vrin. [Google Scholar]

- Rekalidou, G., Karadimitriou, K., & Moumoulidou, M. (2014). Implementation of Lesson Study with students. Collaboration, reflection and feedback. Hellenic Journal of Research in Education, 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Richit, A., Ponte, J. P., & Tomasi, A. P. (2021). Aspects of professional collaboration in a lesson study. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education, 16(2), em0637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricœur, P. (2005). Parcours de la reconnaissance. Trois études. Éditions Stock. Livre de poche Folio essais. [Google Scholar]

- Roorda, G., de Vries, S., & Smale-Jacobse, A. E. (2024). Using lesson study to help mathematics teachers enhance students’ problem-solving skills with teaching through problem solving. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1331674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouiller, Y., & Howden, J. (2010). La pédagogie coopérative: Reflets de pratiques et approfondisse-ments [Cooperative pedagogy: Reflections on practices and deepening]. Chenelière. [Google Scholar]

- Rouiller, Y., & Lerhaus, K. (2003). Pédagogie coopérative: De l’expérience et de la science [Cooperative pedagogy: From experience and science]. Éducateur, 5, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi-Kyburz, L. (2021). Élèves issus de l’immigration: Accueil et intégration à l’école [Students from immigrant backgrounds: Welcome and integration in schools]. In E. Geronimi, & M. Mainardi (Eds.), Désavantages linguistiques et culturels. SUPSI-DFA. Available online: https://in-formazione-inclusione.ch/desavantages-linguistiques-et-culturels/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Saury, J. (2008). La coopération dans les situations d’intervention, de performance et d’apprentissage en contexte sportif [Cooperation in situations of intervention, performance, and learning in a sports context]. In Note de synthèse en vue de l’habilitation à diriger des recherches en sciences de l’éducation. Université de Nantes. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, J.-M., & Pons, R.-M. (2007). Cooperative learning: We also do it without task structure. Intercultural Education, 18(3), 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R.-E. (2014). Cooperative learning and academic achievement: Why does groupwork work? Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 30(3), 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uffen, I., de Vries, S., Goei, S. L., van Veen, K., & Verhoef, N. (2022). Understanding teacher learning in lesson study through a cultural–historical activity theory lens. Teaching and Teacher Education, 119, 103831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K., Meredith, C., Packer, T., & Kyndt, E. (2017). Teacher communities as a context for professional development: A systematic review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 61, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldman, M. A., Doolaard, S., Bosker, R. J., & Snijders, T. A. B. (2020). Young children working together. Cooperative learning effects on group work of children in Grade 1 of primary education. Learning and Instruction, 67(1), 101308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergnaud, G. (1985). Concepts et schèmes dans une théorie opératoire de la représentation [Concepts and schemes in an operative theory of representation]. Psychologie Française, 30, 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Vergnaud, G. (1989). La formation des concepts scientifiques. Relire Vygotski et débattre avec lui aujourd’hui [The formation of scientific concepts. rereading vygotsky and engaging with him today]. Enfance, 42(1–2), 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergnaud, G. (1996). Au fond de l’action, la conceptualisation [At the bottom of action, conceptualization]. In J.-M. Barbier (Ed.), Savoirs théoriques, savoirs d’action (pp. 275–292). Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Vinatier, I. (2012). Ce qu’apprend un maître formateur de son activité de conseil: Une perspective longitudinale [What a Mentor Teacher Learns from Their Advisory Activity: A Longitudinal Perspective]. Travail et Apprentissages, 10, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, Å. K. H., Skaftun, A., & McTigue, E. M. (2020). Literacy practices in co-taught early years classrooms. Study protocol: The Seaside case. Nordic Journal of Literacy Research, 6(4), 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, H. (2018). Noticing in pre-service teacher education: Research lessons as a context for reflection on learners’ mathematical reasoning and sense-making. In G. Kaiser, H. Forgasz, M. Graven, A. Kuzniak, E. Simmt, & B. Xu (Eds.), Invited lectures from the 13th international congress on mathematical education. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. K. (1981). The case study as a serious research strategy. Knowledge, 3(1), 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Teacher | Pupils | Cooperative Learning Cycle Activity Evaluation (to Be Completed by the Teacher) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive interdependence | Ensures that pupils cannot complete the task independently of each other | Must work together to achieve learning objectives | |

| Individual responsibility | Evaluates each point raised personally. Ensures that the task is not split into separate parts | Everyone participates in different parts of the activity. The participation, frequency, duration, intensity and relevance of each pupil may vary | |

| Direct and simultaneous indirect interactions | Organises the space (chairs, tables). Determines the size, composition and role of each group of pupils | Interactions/interaction. Exchange of information and views in several groups at the same time | |

| Cooperation competences | Explains what competences will be developed and how they relate. Explains the task. Provides the necessary support, tools. Provides opportunities to test the activity. Assesses the competences involved. Defines learning objectives/targets and social inclusion objectives | Develop cooperation skills. Integrate learning and social skills at the same time | |

| Evaluation of group performance in cooperative learning | Teacher led or not | Performance is assessed in two ways: learning objectives, social skills | |

| Elements of the cooperative learning framework (covered in full or in part) | No need to explain to students the reasons for choosing a particular activity structure (the teacher must explain only during the activity (reflecting on the experience)) | Developing group work with a common goal, a common classroom culture, knowledge and thinking, communication and cooperation skills, and the sharing of knowledge and skills |

| Date of Lesson | Grade, Number of Pupils | Years of Experience of a Teacher Using Cooperative Learning Methodologies | Qualification Category of Teacher |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle I, 14 April 2022 | Grade 1, 28 pupils (7 years) | 4 years | Senior teacher, 1 observer |

| Cycle II, 26 April 2022 | Grade 1, 26 pupils (7 years), 2 of whom have special needs | 4 years | Senior teacher, 2 observers |

| Cycle III, 3 May 2022 | Grade 1, 28 pupils (7 years), 1 of whom has special needs | 4 years | Teacher-methodologist, 3 observers |

| Lesson Cycle by Lesson Study | Examples of Pupils’ Experiences of Positive Interdependence and Interactions in Appropriate Expression | Attribute not Expressed or Partially Expressed |

|---|---|---|

| Cycle I | The girl realises that she is very connected to the other members of the group. She is very active and encourages her friends. Knows how to work together, has strong social competence (observer 1, girl 1) The girl tries very hard to make sure that all the tools are put away neatly. Encourages her friend sitting next to her. She is responsible not only for herself but also for the activities of the friend sitting next to her, as the team is made up of pupils with different levels of achievement (observers 1 and 2, girl 2) Encourages other members of the group to participate in common activities. Reminds group members what to do. Expresses their opinions. Takes the initiative (observer 2, girl 3) Quickly completed his/her tasks, was interested in the result, watched to see if all group members had counted the steps. Read the tasks clearly, watched to make sure they were done correctly by group mates (observer 3, girl 2) | The girl is shy. Listens carefully to the instructions of her group mates (observer 1, girl 3) Engagement in shared activities is short-lived, quickly distracted. Does not discuss with group members, does not express her opinion (observer 2, boy 1) Worked mainly individually, checked tasks given by others but did not offer to help or check herself (observer 3, girl 1) Worked mainly individually, made sure that everyone completed the tasks on time (observer 3, girl 3) |

| Researchers’ comment: Some children demonstrate a high level of cooperative learning culture, while others lack social skills. | ||

| Cycle II | The group consists of children of different abilities. Good relationships are observed among all group members. The girl interacts with everyone, discussing how to do the tasks better. The girl’s creativity and some mathematical abilities are evident. Quickly completes tasks and consults with others. (observer 1, girl 1) The boy realises that he is very connected to the other members of the group because he always tries to consult. Always makes sure that everyone finishes their work and encourages those who are lagging behind. (observers 1 and 3, boy 2) Engages in a conversation with the teacher. Raises her hand and tries to quietly express her opinion about the castle on display. The assistant encourages him and praises him for his efforts. He keeps looking at the hourglass, holds it up. (observer 1, boy 3) After completing his tasks, he is interested in the result, and sees if all the group members have counted the steps (observer 2, boy 3) | She worked mainly individually, checking tasks given by others, but did not offer to help or check herself (observer 2, girl 1) Pupil was episodically engaged in the activity, not always focused, often off topic (observer 3, girl 1) |

| Researchers’ comment: Although the pupils are only 7 years old, they demonstrate a high level of communication skills, as they are able to listen to each other and give advice. The child with special educational needs in this group has a positive attitude and is well understood. | ||

| Cycle III | At first, he watched the reactions of others and then got involved. Exchanged information very willingly (observer 1, boy 2) Actively engaged in the shared activity. Exchanged information intensively and cordially (observer 1, boy 3) Concentrates, completes tasks more independently, observes the work of other groups, works consistently within his/her own group (observers 2 and 3, girls 2 and 3) Encourages other group members to participate in joint activities. Reminds group members what to do. Speaks up, takes the initiative (observer 3, boy 1) | She watched others more than she worked. Episodically exchanged information, was more willing to help (observer 1, girl 1) Distracted, falls on another child, looks at another’s work, shows no initiative (observer 2, boy 1) Does not get involved in group activities. Prefers to work individually, engages in activities he likes. When reminded by other group members, completes his/her task. Does not discuss with group members (observer 3, girl 3) |

| Researchers’ comment: Some children demonstrate a high level of cooperative learning culture, while others lack social skills. | ||

| Lesson Cycle by Lesson Study | Examples of Experiences of Pupils Expressing Individual Responsibility and Cooperation in an Appropriate Way | Attribute Partially Expressed or not Expressed |

|---|---|---|

| Cycle I | Takes the initiative to divide the responsibilities of group mates. She volunteers to be a reader and a checker. She offers the role of constructor and role of response verifier to one friend and time-keeper to another. Cooperates actively in the group. Responsible and effective performance is observed in achieving all tasks. Does not overshadow the others with her initiative, always talks to the girls and asks for their opinion (observer 1, girl 1) It is clear that this member of the group feels the responsibility of having to work with others on tasks. She listens carefully to the task, makes her own observations and consults the others. This girl does not get lost in situations. Takes initiative (observers 1, 2 and 3, girl 2) This girl tries to contribute to the task. She tries to solve the steps and find the right blocks. At the same time she keeps a close eye on the time. Announces that the allotted time is up (observer 1, 2 and 3, girl 3) | Performed the individual task and his/her duty. After the teacher’s explanation, constructed a castle together with group mates. Communicates minimally with group mates, watches when others talk (observer 3, girl 1) |

| Researchers’ comment: Even first-graders were able to feel responsible and not only fulfilled their roles in group work, but also helped their friends in the group. | ||

| Cycle II | Takes responsibility for the work of the group. Read the tasks aloud. Explains further to friends. Reminds the time-keeper to be attentive and to warn when the time for work is up. Grasps all tasks quickly and offers options for completion, giving advice to the friend sitting next to her. Good communication skills of the girl, which also facilitates cooperation with friends (observer 1, girl 1) The boy also feels important in his role. He checks the answers. He tries very hard, consults his friends (observer 1, boy 2) Actively participated in all tasks. Takes the initiative, invites all members of the group to discuss, makes suggestions (observer 2, boy 3) Took the initiative, cooperated actively during all activities (observer 3, girl 3) | A boy quietly watches his friends work. He tries to count by himself. He fails. The assistant provides a counting aid. He partially completes the task, tries to find the right blocks. The girls advise him on which blocks to put together. The boy does not seem to need a group. He mostly observes. He does not initiate interaction with the group (observer 1, boy 3) He did his individual task and his duty, but did not build the castle. Has minimal contact with his group mates, observes when others are talking (observers 2 and 3, girl 1) Quickly solved the steps of the first task and handed it to the evaluator. After completing the actions, did not participate actively in the group activities any more, but did his own thing or watched others confer (observers 2 and 3, boy 2) |

| Researchers’ comment: Although individual responsibility was evident in the activities of most pupils, some of them may be passive observers rather than actively cooperating. | ||

| Cycle III | He participated in the activities responsibly, with integrity, and worked all the time. Cooperation was smooth (observer 1, boy 2) Worked intensively, made the work relevant and important to the end. Worked in a focused and intensive way (observer 1, boy 3) Completes tasks with concentration, at a reasonable pace. Takes care that everyone completes the task on time, reads the task to all group members, and repeats it when asked. Explains intensively to his group member (boy) where his tasks are and how to find the blocks (observers 2 and 3, girl 2) Performs her task well. She tries to help the other group members. Cooperates with group members, expresses himself and listens to others (observer 3, boy 1) | Participation in activities was sporadic and low-intensity. Cooperation was slow (observer 1, girl 1) Counts at a similar pace to other group members, rocks on a chair, engages in activities when prompted (observer 2, boy 1) Tries to do his/her task but needs to be reminded. The activity gets boring quickly. Difficulties in cooperating with other students (observer 3, girl 3) |

| Researchers’ comment: Pupils are able to complete tasks and provide targeted assistance to their classmates. | ||

| Lesson Cycle by Lesson Study | Examples of Experiences from the Pupil Evaluation Group Activities | Attribute Partially Expressed or not Expressed |

|---|---|---|

| Cycle I | She suggested that the group’s activities be rated excellent (green). The girl knows what she did well and why she did well, she is able to communicate well with her group mates (observer 1, girl 1) She rated the activities as excellent, although it might be more difficult to explain what she did well and what she needs to do better. The success of the work is group-oriented, so the girl expresses her opinion confidently (observer 1, girl 2) Actively participated in all activities and coloured the whole target green. This means that the activities were performed excellently, without any complaints (observer 3, girl 2) | It was hard to make sense of it. Observed friends and evaluated similarly (observer 1, girl 3) Willingly completes the assigned task. Sometimes forgets her role. Takes an interest in the group activities but does not share his/her experience. Interested in activities not related to the task (observer 2, boy 1) Did not actively participate in all activities but coloured the whole target green. Suggested ideas when thinking of the name of the castle, when creating the presentation of the castle, but only observed the activities (observer 3, girl 1 and girl 3) |

| Researchers’ comment: Some students are able to evaluate their own and their group’s work adequately, while others have not yet developed this ability because they do not have their own opinion on the matter. | ||

| Cycle II | A girl quickly comes to her senses. The success of the work is group-oriented, so the girl expresses her opinion boldly and cooperates actively with the group (observer 1, girl 1) She is able to evaluate her own work and the work of others according to the criteria given by the teacher. She is able to communicate with group members (observer 1, boy 2) Participated actively in all activities and coloured the whole target green. Actively participated in the creation of the castle presentation, presenting the castle of her group (observer 2, boy 3) Achieved the learning objective through cooperation, good social skills. Team leader. Able to bring classmates together for a common goal (observer 3, girl 3) | Observing how your friends evaluate your work. Tries to find a green pencil, but doesn’t have one. The assistant suggests looking for a green felt-tip pen. The boy is delighted when he finds it and marks his work with this colour. Lack of activity. Passive observation, does not participate in discussions but responds well to the interaction of the helping adult (observer 1, boy 3) Did not actively participate in all activities but coloured the whole target green. Not very active in creating the presentation of the castle, observed (observer 2, girl 1 and boy 2) |

| Researchers’ comment: Most pupils assessed their activities adequately, based on the criteria. | ||

| Cycle III | Achieved the learning objective, very good social skills. Teamwork was good, good sharing of knowledge and skills (observer 1, boys 2 and 3) Understands the learning objectives and works towards them. Very social. Very concerned about the overall outcome. Goes to the other group members, helps, mobilises by saying “Which castle are we going to build?”, “We don’t have a brown one.”, “Let’s do it now, everyone.” Discusses with others the name of the castle, its purpose (observers 2 and 3, girl 2) Learning objectives are sufficiently clear; they understand that they are important for all group members. Understands that the overall result is important. Makes an effort, clarifies (observer 2, girl 3) Participates actively in all activities. Excellent social skills. Works hard to build a team. Takes initiative. Shares knowledge (observer 3, boy 1) | Achieved the learning goal (with help), social skills are average. Lack of initiative during group work (observer 1, girl 1) Learning objectives need to be reminded. Social skills are still developing. Little interest in the overall goal and outcome of the group, engages in extraneous activities (observer 2, boy 1) Completes the assigned task when prompted by group mates. Does not share his/her experience. Does not take an interest in group activities. Interested in activities not related to the task at hand (observer 3, girl 3) |

| Researchers’ comment: Some students not only completed their tasks and activities responsibly, but also assessed themselves adequately. There were cases where a child found it difficult to engage in the activity, which made it difficult for them to assess their work adequately. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jakavonytė-Staškuvienė, D.; Bernotienė, R. Learning Through Cooperation in the Activities of 1st-Grade Pupils (7 Years Old) Using the Lesson Study Methodology: The Case of One Lithuanian School. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101303

Jakavonytė-Staškuvienė D, Bernotienė R. Learning Through Cooperation in the Activities of 1st-Grade Pupils (7 Years Old) Using the Lesson Study Methodology: The Case of One Lithuanian School. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101303

Chicago/Turabian StyleJakavonytė-Staškuvienė, Daiva, and Renata Bernotienė. 2025. "Learning Through Cooperation in the Activities of 1st-Grade Pupils (7 Years Old) Using the Lesson Study Methodology: The Case of One Lithuanian School" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101303

APA StyleJakavonytė-Staškuvienė, D., & Bernotienė, R. (2025). Learning Through Cooperation in the Activities of 1st-Grade Pupils (7 Years Old) Using the Lesson Study Methodology: The Case of One Lithuanian School. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101303