1. Introduction

Technology has turned the world into one global village where in-person and online encounters with foreign cultures are the norm (

Chen, 2022). However, these can be intimidating when one doesn’t know how to navigate cultural differences. Intercultural competence (IC) bridges this gap, fosters understanding and helps create meaningful connections across cultures (

Deardorff, 2021). Technology can be a great support for acquiring this valuable skill, especially in today’s multicultural educational environment, both on campuses and online, preparing students for the changing technological and social landscape (

Trinh, 2021).

Cross-cultural differences can be acute in societies with a history of conflict such as Israel. Israel’s population, estimated at around 9.8 million in 2023, is predominantly Jewish (73.2%), with Arabs comprising approximately 21.1%, among the Arab population, the vast majority are Muslims (

Rhodes, 2023). Arab citizens differ from the Jewish majority in religion, language, and culture, and often face systemic discrimination and inequality (

Rumeau, 2022). The Jewish population is internally diverse, both ethnically and religiously. Ethnically, Jews are broadly categorized into Ashkenazi (of European origin) and Mizrahi (from Middle Eastern and North African countries).

Israel’s main cultural groups are secular Jews, religious Jews and Muslim Arabs, co-living with other minorities from diverse ethnic backgrounds (

Abu-Saad, 2019). Religiously, Israeli Jews self-identify along a spectrum: about 45% are secular (Hiloni), 33% are traditional (Masorti), 13% are religious (Dati), and 9% are Ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) (

Rhodes, 2023;

Rumeau, 2022). The Haredi community is the fastest-growing segment, with a high fertility rate of 6.5 children per woman and a population growth rate of around 4% annually. As of 2022, Haredim numbered approximately 1.28 million, making up 13.3% of the total population, and are projected to reach 16% by 2030 (

Yiftachel, 1992).

There have been multiple efforts to connect Arabs and Jews in online educational settings in Israel, successfully employing technology to bridge cultural differences safely (

Ganayem et al., 2020;

Shonfeld et al., 2021;

Masry-Herzallah & Amzalag, 2021). Cross-cultural encounters are challenging at first, but over time, one can expand horizons, learn about others’ perspectives and enrich one’s worldview. This article explores the potential of online platforms to influence IC among Israel’s Arabs and Jews. The methodology was developed and applied by the Technology and Education Center (TEC) at a teacher education college, pioneering the use of digital environments as a neutral ground for progressive cross-cultural interaction. Given Israel’s cultural context, the TEC model’s graduality offers safe exposure for groups who hold prejudices and resent the “other” culture (

Shonfeld et al., 2021). However, a relatively new methodology for influencing IC is in-person and virtual simulation activities. The latter are conducted through avatars in 3D environments where students can feel as if they are in real-life simulations (

Shonfeld & Kritz, 2013). The present study explores the potential of VW and Zoom platforms to influence students’ intercultural attitudes. This comparison is based on the assumption that virtual worlds (VW) enhance positive experiences by enabling real-time interactions in ways that Zoom cannot.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Intercultural Competence

Meeting different cultures can be intimidating but can also be bridged through the ability to see, accept and understand others without bias or judgement. Intercultural competence (IC) involves knowledge, skill and attitude to navigate cross-cultural encounters (

Deardorff, 2021;

Savicki, 2023). IC characteristics include flexibility, open-mindedness, and positive attitudes toward other cultures (

Deardorff, 2021); adaptability, sensitivity to and empathy for differences (

Pastori et al., 2018); cultural knowledge; and willingness to learn more. Another important aspect is the self-awareness of one’s own conditioning, allowing for recognition for others’ different backgrounds (

Pastori et al., 2018).

However, IC in a heterogeneous context such as New York City requires different IC than people growing up in cultural conflict as in Israel. Deconstructing the existing prejudice and re-building trust requires efforts to inspire feelings of safety, of being seen, and the willingness to see and understand the other (

Ganayem et al., 2020).

2.2. Change in IC and Attitude

Intercultural competence can be acquired. Many educational programs have successfully fostered IC, especially among pre- and in-service teachers (

Shonfeld et al., 2021) where it is particularly important (

Savicki, 2023).

Such efforts include international study and exchange programs, which are exciting but costly, excluding many from such experiences (

Anis, 2023;

de Castro et al., 2019). Hence the use of ICT for international exchanges has grown in popularity. ICT-mediated education projects have the potential to reduce intergroup prejudice and stereotyping (

Walther et al., 2015) while improving attitudes (

Ribeiro, 2016). In Israel, the Technology and Education Center (TEC) involves culturally diverse pre-service teachers (PSTs) in the goal of advancing both their IC and ICT literacy (

Ganayem et al., 2020). Using a digital environment as neutral ground, its methodology allows for adjustment, reevaluation of old beliefs and the formation of new impressions (

Shonfeld et al., 2021).

Another methodology for shaping IC is online collaborative learning where culturally diverse individuals work toward a common goal on a neutral digital platform (

de Hei et al., 2020). The group’s cultural diversity manifests in different working and communication styles (

Nguyen et al., 2022), and IC grows in conflict management and collaboration (

Austin & Turner, 2020). However, a relatively new methodology for influencing IC is virtual simulation.

2.3. Virtual Simulation

Educational methodologies such as simulations and virtual simulations, e.g., via Zoom, immerse learners in quasi real-life scenarios where their proactivity and critical thinking in response to a situation constitutes the learning process (

Colvin et al., 2020). Simulations encourage collaborations, making them a perfect opportunity to have members of diverse cultures work together toward problem-solving (

Benjamin et al., 2021) while remaining respectful of the ¨other¨ culture (

Colvin et al., 2020;

Lee et al., 2022;

Li et al., 2024;

Wu et al., 2021). Virtual simulations can be explained through Kolb’s experiential learning cycle (

Kolb, 1984), according to which learning occurs through a process of four stages: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. Thus, the virtual intercultural simulations in either VW or Zoom provided participants with concrete experiences of diversity and collaboration and facilitated abstract conceptualizations about the value of empathy, patience, and openness toward the other. Simulation-based learning has emerged as a vital tool in promoting cultural competence, allowing participants to engage in real-life scenarios that enhance their understanding and sensitivity towards diverse cultures. This experiential approach not only fosters awareness but also equips individuals with practical skills necessary for effective interaction in multicultural environments (

Clary et al., 2022). The group’s cultural diversity offers multiple ideas, knowledge, and skills. This encourages participants to navigate differences and learn about other cultures’ ways of doing things (

Colvin et al., 2020;

Lee et al., 2022).

Although virtual simulation was widely studied among health professionals (

Chae et al., 2021), simulation in the virtual world has not been explored much in education, and this study aims to explore the potential of virtual simulations in enhancing cultural competence, particularly through immersive experiences that reflect real-world intercultural interactions.

Virtual simulations encourage learners to overcome bias and prejudice (

Jauregi-Ondarra & Canto, 2022;

Zhang, 2019), stimulate tolerance (

Lee et al., 2022), and strengthen empathy and understanding in cross-cultural interactions (

Benjamin et al., 2021). These types of training are especially valuable for professionals who encounter, influence or collaborate with culturally diverse groups, such as teachers (

Kong et al., 2017). Virtual simulations safely expose learners to various potential scenarios of their post-education reality (

Pottle, 2019;

So et al., 2019), such as having intercultural experiences. The virtual simulation allows for learning through play and learning from mistakes (

Jauregi-Ondarra & Canto, 2022;

Pottle, 2019).

2.4. Virtual Worlds

Virtual simulation experiences can be taken to yet another level of realism using virtual worlds (VW)-digital environments constructed with 3-D imagery presenting a rich, authentic, and interactive space enabling movement, speech, and use of objects. Virtual spaces can be designed as neutral ground where everyone feels respected (

Anis, 2023;

Colvin et al., 2020). VWs also allow the creation of avatars as realistic and culturally reflective virtual representations of the user, which are then used to move and communicate with peers around the platform (

Shonfeld & Kritz, 2013). Thus, in culturally disharmonious societies such as Israel, the VW represents safety and neutrality where individuals would be more inclined to meet with ¨rivals¨ (

Ganayem et al., 2020). In addition, in a mediated environment like VWs, ‘presence’ is defined as the subjective feeling of “being there,” (

Slater & Wilbur, 1997;

Lombard & Ditton, 1997) can enhance engagement and relational responsiveness in virtual contexts, (

Slater & Sanchez-Vives, 2016).

2.5. Beyond Zoom: Virtual Worlds in Action

Virtual platforms have evolved dramatically, with avatar-based virtual reality (VR) emerging in addition to traditional synchronous tools like Zoom. While both platforms facilitate remote collaboration, immersive virtual platforms offer distinctive advantages, such as sense of presence (SoP), emotional engagement, and the development of teamwork. One of the strengths is the ability to create a high level of immersion that enhances the user’s feeling of “being there”. This immersive quality enables users to engage with the environment emotionally and cognitively in a way that reflects real-life experiences (

North & North, 2016). Such experiences lead to better memory retention, stronger emotional impact, and deeper learning, as shown in studies linking SoP and immersion with improved memory (

Cadet & Chainay, 2020;

Makowski et al., 2017).

Avatar-based VW also allows users to interact with one another in simulated, lifelike environments, which significantly benefits collaborative learning and teamwork. In educational and training contexts, immersive platforms promote motivation, engagement, and the ability to understand complex ideas through visual and interactive representation (

Lønne et al., 2023). These lifelike encounters allow users to practice real-world scenarios without real-world consequences, enhancing confidence and competence. Moreover, it is found to increase emotional arousal, which in turn boosts attention, motivation, and learning outcomes (

Lei et al., 2022;

Lønne et al., 2023). Unlike Zoom, which facilitates straightforward communication but lacks environmental or emotional depth, VWs immerse learners in engaging scenarios that stimulate active participation and emotional experience (

Lønne et al., 2023).

When it comes to team performance, VWs offer advantages in enabling interactive, shared spaces that support teamwork and social interaction (

Fraser et al., 2022).

Massey et al. (

2024) found that in collaborative virtual environments (CVEs), performance was significantly enhanced by the users’ ability to interact effectively within the shared space (“doing there” presence). While over-immersion—being too absorbed—can sometimes detract from performance, the controlled use of immersion leads to better coordination, understanding of task progress, and smoother group dynamics. These findings suggest that VW not only supports team-based tasks but can also improve teamwork by simulating real-time collaboration in ways that Zoom cannot. This research examines the advantages of VW simulation for promoting cultural competence compared to the Zoom environment.

3. Methodology

This research employed a mixed-methods approach to investigate the contribution of a Virtual World (VW) platform to promote Intercultural Competence (IC). A pedagogical intervention consisting of an educational technology course was implemented with undergraduate students from multiple teacher education colleges. Participants were divided into two major groups: One group utilized a VW platform for interactive simulation activities and meetings, providing an immersive virtual classroom environment with spatial movement and flexible interaction. The other group engaged with the same content via Zoom for synchronous class sessions and by watching recorded videos of the simulations.

Zoom was selected as the primary platform for the virtual intervention because the Ministry of Education provided free Zoom licenses to all educators during the year of the study. This ensured seamless access, consistent functionality, and eliminated cost barriers for participants. Other platforms, such as Google Meet, were not supported by the Ministry at the time, making Zoom the most practical and inclusive choice for conducting the intervention.

The pedagogical approach involved immersing participants in IC content through a series of simulations representing educational pedagogy and cross-cultural issues, and cultural-based classroom confrontations. The main research question was whether the active engagement offered by the VW simulations would result in a greater impact on student attitude and development of IC than the passive observation of recorded simulations by the Zoom group.

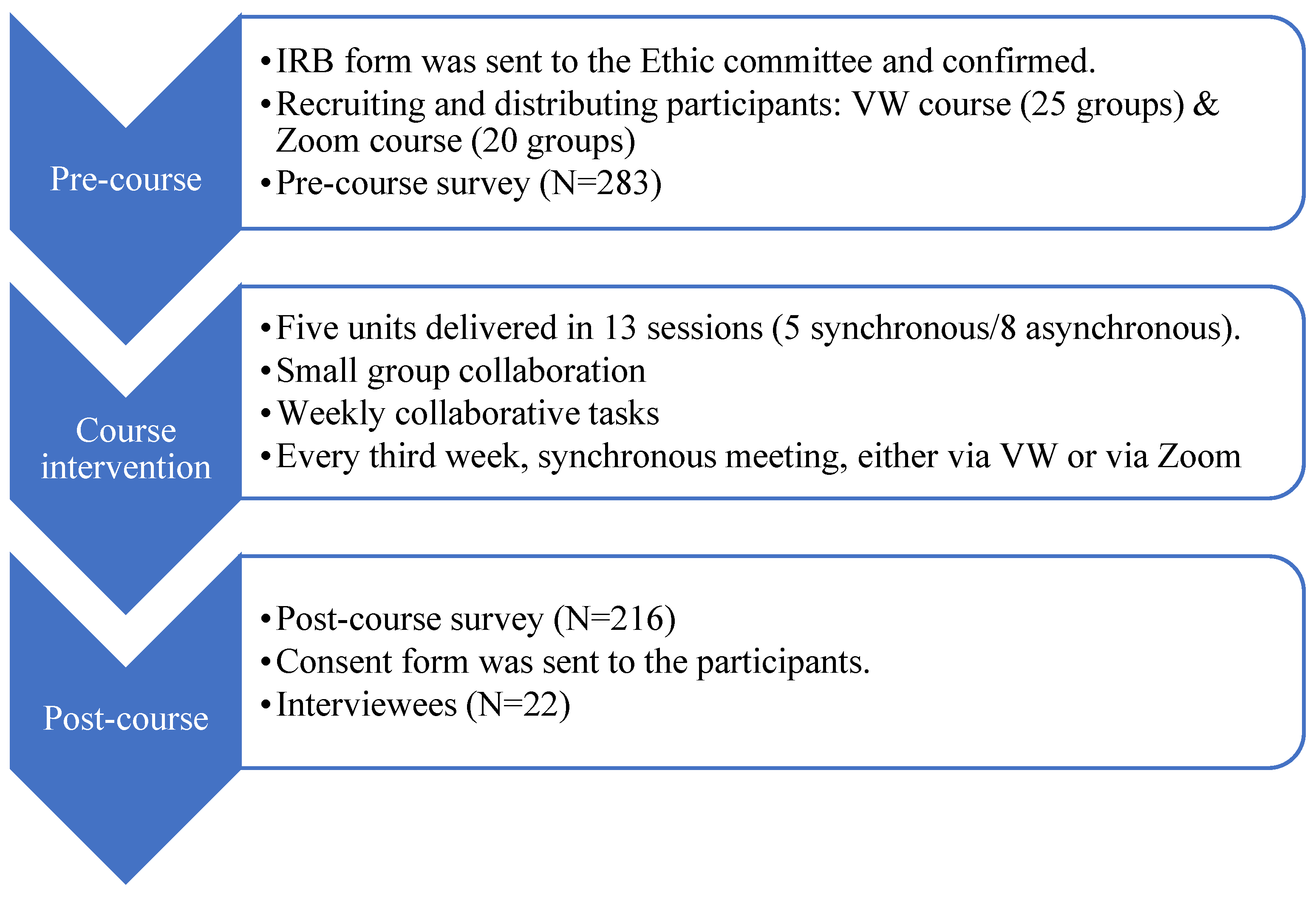

Moodle served as the platform for delivering the course content to both groups, ensuring that each had access to the units and instructions relevant to their assigned platform. The course comprised five units delivered in 13 sessions (5 synchronous/8 asynchronous). Each unit included one or two asynchronous sessions and one synchronous one. All students and instructors met initially in the same space for course introduction. Then students were divided into two major groups (VW & Zoom), and within each major group students were divided into small work groups (N = 6), an effort was made to ensure an equal number of Arab and Jewish participants in each group, based on the number of participants from each college. and assigned to VW rooms or Zoom rooms where they collaborated on unit tasks for the duration of the course. The asynchronous, small-group sessions were weekly meetings conducted via the Moodle LMS platform. Every third week, students met synchronously, either via VW or via Zoom. All asynchronous sessions were online.

Students received course credit for completing the unit task, which was assessed using rubrics that allocated separate grades for individual contributions and group work. The assessment was identical for both major groups. For both VW and Zoom environments, various simulations were constructed around topics in educational pedagogy and cross-cultural issues. In these scenarios, the VW environment revolves around the avatars. For example, a participant in the study might be assigned an avatar that differs from the participant in real life. The student would then explain how a teacher should handle certain classroom dilemmas. While in the Zoom environment, the same dilemmas are presented as simulations via video clip and discussed within the small subgroups. Zoom group students did not have access to VW technology—they could not change their appearance as in the VW scenario to experience “being in others’ shoes” as illustrated in

Figure 1.

The platform for the VW activities was OpenSIM© TEC Island, a platform simulating a classroom where the students can move their avatars around, change clothes and figures, speak and chat, attend a lesson with the entire class or meet in small groups. In addition to virtual classroom furniture, TEC Island includes a variety of cultural elements and locations.

Figure 2 presents the entrance to the TEC island.

The quantitative research utilized a survey assessing differences in intercultural competence among students in a VW platform compared to those participating via Zoom, the questionnaires are described in detail below. The survey was distributed via email and completed online using the Qualtrics platform (qualtrics.com) twice—at the beginning and end of the course—to measure whether participant’s IC towards others changed throughout the course and the contribution of the online platforms.

For the qualitative research, a total of 22 semi-structured interviews were conducted with 14 participants from the VW group and 8 from the Zoom group. Participants were purposely sampled to represent both Jewish and Arab PSTs across institutions and platforms. While the preceding quantitative phase drew on a random sample from a broader population, the qualitative phase relied on purposeful sampling, which is generally more appropriate when the aim is to gain deeper insights from information-rich cases (

Silverman, 2015;

Stake, 2005). Thus, respondents were selected based on their ability to illuminate the phenomenon under study, and their willingness to be interviewed further shaped the composition of the sample (

Shkedi, 2019). Data saturation was reached after approximately 20 interviews, as no substantially new themes emerged in the final two transcripts.

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim in the original language (Hebrew or Arabic), then translated into English by bilingual research assistants and cross-checked by a second bilingual researcher to ensure semantic accuracy and minimize translation bias. The analysis followed a multi-step coding protocol: one researcher first conducted open coding on a subset of transcripts, which was then reviewed by three additional researchers to refine a shared codebook. The remaining transcripts were coded using this protocol, with iterative adjustments as needed. Intercoder agreement was assessed on 25% of the transcripts using Cohen’s Kappa, yielding coefficients between 0.76 and 0.81, indicating substantial reliability. To support thematic clustering, Claude AI (version 2.1, 2024 release) was used in the preliminary stages. Anonymized transcript excerpts were provided as inputs, and Claude generated potential groupings of codes. These outputs were considered as suggestions only, with all final coding, categorization, and interpretations completed by the research team. The team verification and consensus ensured that validity and transparency remained central to the analysis process.

Participants were invited to take part in this research through a Zoom interview, having been clearly informed that their participation was voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time. They were also assured that all collected data would be used solely for research and publication purposes, with strict measures being taken to maintain their anonymity.

The illustration of the research methodology can be found in

Figure 3.

3.1. Research Population

The study’s participants consisted of education PTSs, predominantly women, (mean age = 30), recruited from six teacher education colleges with Arabs and Jews from various regions. The majority of students enrolled in these colleges are women. Participants were assigned either to the VW group or the Zoom group. It was the students’ decisions if they wanted to try VW. Those who did not log in to VW continued with the Zoom group.

The students were then divided into small mixed ethnicity groups of 5–6. The VW course had 25 groups, while the Zoom course had 20 groups. Each of the instructors, who came from varied intercultural and ethnic backgrounds, was responsible for overseeing three to four groups. For a detailed breakdown of the participants’ demographics and other characteristics, see

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Results showed several significant differences between the groups. A significant difference was found in levels of religious observance, t = 2.00, p < 0.05, while participants in the Zoom group (M = 3.50, SD = 2.10) reported higher levels than those in the VW group (M = 2.80, SD = 2.20). In addition, the groups differed significantly in ethnicity, χ2 = 31.60, p < 0.01, and in main language, χ2 = 7.70, p < 0.001. Specifically, the VW group included a higher proportion of Jewish participants (74.8%) compared to the Zoom group (37.1%). Conversely the Zoom group included a higher proportion of Arab participants (62.9%) compared to the VW group (25.2%). In addition, a greater proportion of VW participants reported Hebrew as their main language (84.0%) compared to Zoom participants (70.1%).

There were some differences between the VW participants and the Zoom participants as presented in

Table 2.

The VW group had more Jewish students than Arab students while the Zoom group had more Arab students than Jewish students.

3.2. Instruments

The study employed two instruments to measure IC, willingness to engage with other cultures, and intercultural sensitivity, adapted to the study’s objectives and context.

1. CCD-Intercultural Competence: Drawing from Deardorff’s Delphi-model-based definition of intercultural competence (

Deardorff, 2006), this instrument was translated into Hebrew and validated by back translation and a panel of eight researchers. It consists of 18 items reflecting various aspects of IC, achieving a high-reliability score (α = 0.95).

2. ISS-15: Intercultural Sensitivity: Based on

Wang and Zhou (

2016), this 15-item measure assesses the degree of intercultural sensitivity on a 1–5 Likert scale, with 5 representing the highest level. This instrument was also translated into Hebrew and validated by back translation and a panel of eight researchers.

To examine the construct validity of the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principal component extraction with varimax rotation. All 15 items were included in the analysis, with listwise deletion for missing data. The criterion for factor retention was an eigenvalue greater than 1. Items with loadings below 0.40 were suppressed.

Two factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were retained, together accounting for 77.87% of the total variance (Factor 1 = 50.91%; Factor 2 = 26.96%).

Factor 1 (Intercultural Attitude) captured negative affective and evaluative reactions toward culturally different others, such as discouragement, upset, or avoidance. Items loading highly on this factor included, for example, “I often get discouraged when I am with people from different cultures” (0.78), “I get upset easily when interacting with people from different cultures” (0.76), and “I think people from other cultures are narrow-minded” (0.71). This factor was found reliable in T0 for group VW (0.84) and Zoom (0.80).

Factor 2 (Satisfaction with Communication) reflected confidence and engagement in intercultural encounters, such as sociability and self-confidence. High loadings included “I feel confident when interacting with people from different cultures” (0.79), “I can be as sociable as I want to be when interacting with people from different cultures” (0.75), and “I enjoy interacting with people from different cultures” (0.74). This factor was found reliable in T0 for group VW (0.89) and Zoom (0.87).

Item 14 (“I am sensitive to my culturally distinct counterpart’s subtle meanings during our interaction”) showed cross-loading and did not load cleanly on either factor. Therefore, item 14 was excluded from factor 2. The factor analysis results are detailed in

Table 3.

To validate this structure, we conducted a Confirmatory Factor Analysis, according to the two-factor solution. The CFA analysis yielded satisfactory goodness of fit indices χ2 (83) = 154.1, p = 0.001; CFI = 0.93; GFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.05, with all loadings above 0.52.

Two factors were defined for this research according to

Table 3, Intercultural attitude, and satisfaction with communication.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Results

4.1.1. Differential Impact on Intercultural Sensitivity and Longitudinal Change

The study examined the impact of varied online instructional activities on students’ intercultural competence, comparing the effectiveness of Virtual World (VW) and Video Conference via Zoom. A repeated-measures MANOVA test was employed, utilizing data collected from two distinct instruments: the Intercultural Competence Deardorff questionnaire (CCD), and the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale-15 (ISS-15). In this analysis the within-subjects factor was time, and the between-subjects factors were platform and ethnicity. The number of participants was 122 for the VW group and 97 for the Zoom group.

The repeated measures MANOVA enabled comparison of the progression of IC in both groups, providing a comprehensive analysis of the data collected at two different time points, offering insights into participants’ intercultural sensitivity development.

4.1.2. Intercultural Competence Assessment via the CCD Questionnaire

The data obtained from this questionnaire underwent a MANOVA test, which identified a modest yet statistically significant increase in the IC scores for both the VW and Zoom groups. Initially, the mean score was 4.0 (SD = 0.56), which rose post-intervention to 4.1 (SD = 0.57), F(1, 216) = 3.8, p = 0.05, η2 = 0.018.

Comparative analysis between the two groups revealed no significant difference in the efficacy of the instructional method on IC, F (1, 216) = 2.07, p = 0.15, ns. Similarly, religious affiliation showed no significant effect on IC scores, F(1, 216) = 2.9, p = 0.08, ns.

These results highlight the effectiveness of IC education, regardless of the delivery platform or religious background.

Figure 4 presents a slight difference between Zoom group and VW group. T1 are IC Means before the course and T2 are IC Means after the course.

The results showed no significant difference between the Zoom group and the VW group.

4.1.3. Assessment of Intercultural Sensitivity: ISS-15 Questionnaire

This questionnaire gauging intercultural sensitivity underwent a MANOVA analysis to determine any significant shifts in PSTs’ perceptions after the course. Findings indicated stability, with no significant change among the groups, F (1, 214) = 0.59, p = 0.44, ns, no notable differences between the two groups, F (1, 214) = 0.14, p = 0.70, ns, nor any significant distinction for religious affiliation, F (1, 214) = 0.59, p = 0.44, ns.

However, for ISS-15 factor of participant satisfaction with communication, a significant distinction emerged for Ethnicity, F (1, 215) = 18.5, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08. Specifically, Arab PSTs reported higher levels of satisfaction with communication (M = 4.0, SD = 0.63) than Jewish PSTs (M = 3.7, SD = 0.57). Moreover, PSTs in the VW group reported higher levels of satisfaction with communication (M = 4.0, SD = 0.80) than the Zoom group (M = 3.6, SD = 1.0), F (1, 214) = 10.66, p = 0.001, np2 = 0.04.

In conclusion, findings show the impact of VW and Zoom platforms on IC activities among PSTs. A key finding is the slight yet noticeable improvement in IC for both research groups, indicating that course activities contributed to the IC of all participants. Despite the overall stability in intercultural sensitivity levels and willingness to engage with different cultures, as shown by the ISS-15 Questionnaire, the subtle increase IC (CCD) scores suggests that the course activities had a foundational impact on the participant’s ability to understand and interact with diverse cultures.

Moreover, while ethnic affiliation did not affect most outcomes, initial variations in interaction were noted, particularly with Arab students initially demonstrating higher levels than their Jewish counterparts, suggesting that cultural and ethnic contexts might play a role in shaping intercultural dynamics.

The results pre- and post-course suggest that activities related to racism, involving participants from diverse backgrounds, slightly influenced individuals’ IC, indicating that IC and sensitivity are complex and multifaceted constructs.

4.2. Qualitative Results

The qualitative research sought to deepen understanding of the program’s contribution. Data is presented by comparing PSTs who experienced a VW (14 interviewees) versus those who observed activities via Zoom (8 interviewees). Interviews were taken anonymously, and hence no names are attached to the quotes below. A consent form was signed by the interviewees and upon acceptance the interview took place via Zoom. Analysis yielded two main categories: positive aspects of the experience; aspects requiring improvement.

- 1.

Positive Aspects of the Experience

- 1.1.

Support in Difficulties

VW participants mentioned the importance of group support. “It was difficult at the beginning […] I managed over time with the help of friends in our work group. If someone got stuck […] we would help.” (A).

1 “One group member helped me […] navigate.” (J). The positive reference to support was expressed by all 14 VW participants, while only 3 out of 8 Zoom participants mentioned support as the technological challenges they faced were limited: “[…] everyone helped each other […]” (J).

- 1.2

Developing Empathy and Accepting Differences:

This issue appeared only among VW participants as cooperation was required, unlike in the Zoom experience. “[…] I really opened up to hearing and listening to other people […]” (J); “[…] I was experiencing something similar to reality” (J). An Arab student emphasizes the importance of the encounter with Jewish students: “I plan to work with my degree in Jewish schools. […] It helps me […] end the racism that exists now in Israel […].” Others mentioned that they already “have friends of all colors, genders, and kinds.”

- 1.3

Familiarity with different cultures:

The experience fostered cross-cultural understanding, regardless of VW or Zoom participation. All interviewees expressed a desire for face-to-face meetings to deepen their cultural knowledge: […] the course helped me get to know other people from other sectors […] it was nice for me to experience and learn more” (J); “I learned that I must respect others and their religion and their culture, and to understand that not the whole world is like my culture […] That’s how I learn […] how to respect their culture […] that’s how I’ll be multicultural” (A).

In the Zoom group, albeit with less frequent meetings, positive attitudes remained strong, saying they wanted additional intercultural encounters: “There’s something that influenced us […] we learned to know them better, and I believe that more healthy conversations are needed […]” (J); “In the last meeting, I knew who the group members were, and we talked a lot”(A).

- 2.

Aspects requiring improvement:

- 2.1.

Problems in Operating the Avatar and Navigating in VW

Eight VW participants reported problems with their avatars and the system. An Arab student says, “There were some disadvantages, especially with the application’s operating system […] moving within the virtual world, which had occasional delays. These technological challenges […] affected the overall experience.” (A). “Being in the virtual world wasn’t easy for me. […] I didn’t really succeed at it […] it was so complicated” (J). Others point out that the avatar disappeared within the world and was moved elsewhere. In contrast, Zoom group members had no difficulties, as they only watched videos of VW activities.

- 2.2.

PC and application overload

Eight VW participants experienced technical difficulties, e.g., slow software, crashes, and navigation issues, especially when there were many participants: “It crashed a lot, I think because there the system was overloaded. […] I didn’t always reach the right room […]” (J). “The software doesn’t work… and it’s outdated” (J); “A lot of people logged in at the same time […] and the world was really lagging” (J). “The moment there were many participants […] it immediately disconnected. It was frustrating […]” (J). A third PSTs’ attitude shifted: “It seemed like it lagged and worked very slowly. But it was really cool at first. […]. I don’t think it fully met the educational goals […]” the student continued. “It was hard to navigate the virtual world. Sometimes it would just throw me into another world. […] And I couldn’t even see my avatar or find myself at all. It was really frustrating” (J).

Zoom group members also reported issues. “The internet was very slow […]” (A). stated, “We had a WhatsApp group, […] (where we) mainly provided technical support to help each other […] When the site crashed for some people, the group couldn’t connect […] I consulted with a colleague, an Arab team member […] I was able to help others with this issue” (J).

- 2.3.

Communication and speech difficulties between participants

Some participants indicated difficulty in communicating, especially from the VW, where collaboration was required. “[Communicating with the Arab students] was a great language difficulty. [Even though] I studied 5 units of Arabic.” (J). In the Zoom group, where less communication was required, only one participant mentioned a difficulty in communicating in Hebrew: “I don’t speak much Hebrew, it was something difficult for me, [but I would] not let the language prevent me from getting to know new things.” (A).

- 2.4.

Difficulties coordinating times

Five VW participants mentioned time coordination issues: “The only challenge is to find a time […] to log in together”(J). Students had difficulty navigating the VW and reaching the meeting point: “The difficulty is that not everyone connects [at the same time] […] it drove me crazy” (J). Work in the

Zoom group was simpler because they were required to watch but not act simultaneously: “[…] it was just [finding common] time and day that were a bit difficult […]” one student commented.

- 2.5.

Ambiguity and frustration regarding the goals and conduct of the course

Seventeen statements from VW participants expressed frustration with the lack of course clarity, technical issues, resistance to multiculturalism and simulations. A Jewish student said, “This is a 1.5 hr course per week. […] our brain can’t handle seeing so many things at once […]. You can’t just send students to 40 places to respond. I really couldn’t follow the instructions […]” (J). In contrast frustration was overcome in the Zoom group: “I didn’t understand, couldn’t hear […] what they were saying on Zoom. At first, it was a bit difficult […] in the end, it was easy, and the group members were nice and respectful […]. I loved this experience” (A); “[…] my experience was good when I succeeded […].” (J). This group contained only three mentions of frustration: “I didn’t quite understand […] what exactly was required of me” (J).

The qualitative findings help contextualize and triangulate the quantitative results. Quantitative analyses revealed a modest but non-significant increase in IC (ISS scores) across both groups, with no platform-based differences. The interview data helped explain these results. Students in the Virtual World (VW) group reported that navigation was often difficult and frustrating, as the need for synchronous meetings within VW introduced usability burdens that sometimes-hindered learning. At the same time, these synchronous encounters fostered group work and cross-cultural support, enabling opportunities for empathy development and a stronger sense of the presence of group members within VW.

In contrast, Zoom participants did not have to cope with advanced technological challenges, as the platform was more familiar and straightforward, so they did not report technical difficulties. They worked effectively both synchronously and asynchronously, but their interactions did not highlight the second category of “developing empathy and accepting differences.” This relative absence may be due to the lower level of immersive presence and fewer synchronous opportunities for deep intercultural engagement. Thus, while VW participants experienced moments of empathy and satisfaction with communication that Zoom participants lacked, these gains were counterbalanced by significant frustrations related to navigation and usability.

Also, collaboration was required of both groups, but some VW interviewees expressed difficulties in communication between group members, and others spoke about the contribution of the group’s mutual support. In contrast, one Zoom participant expressed a language difficulty but tried to communicate and learn. Another category was the “difficulty in scheduling” in both groups as they needed to coordinate time for group work. Both groups viewed exposure to students from other cultures as an added value to the course. Students saw great importance in a face-to-face encounter and an opportunity to meet and get to know the culture of their peers.

5. Discussion

The current research, based on a social experiment, sought to find the most effective digital tools and educational methodologies to bring together Arabs and Jews, and through virtual simulation and multicultural immersion, reduce cultural prejudice and encourage mutual understanding. It is vital to Israel society since the demographic complexity reflects deep social, cultural, and political divisions, particularly between Jews and Arabs. These divisions influence public policy, education, and national identity, shaping Israel’s evolving societal landscape.

In the current research, both the VW and Zoom groups reported a moderate, but significant increase in their IC levels, with no major quantitative differences between the two platforms. However, the qualitative findings provided richer insights into how empathy, collaboration and openness were cultivated throughout the program. To gain a better understanding of the results, they will be compared to past research as well as discussed across the lines of the following models: Theories of Experiential learning and Intercultural Growth; Presence in Digital Environments, Quantitative and Qualitative Discrepancies, Technological Challenges as Both Barrier and Opportunity. The discussion will conclude with an assessment of the implications for Teacher Education.

For the purpose of this research, Jewish and Arab pre-service teachers (N = 283) took part in a virtual cultural exchange aimed at improving their intercultural competence. They were placed in culturally mixed working groups that used either a 3D virtual world or Zoom so that it enabled evaluation and comparison between platform’s effectiveness on fostering participants’ IC. This study builds upon existing research that establishes the effectiveness of digital platforms in cross-cultural online collaboration for improving IC (

de Hei et al., 2020;

Walther et al., 2015;

Shonfeld et al., 2025) and that the design of the interactive learning environment can influence the learning experience. (

Anis, 2023;

Colvin et al., 2020). But the findings challenge the widespread assumption that immersive technologies such as VWs are the supreme methodology and outperform the classic video conferencing for fostering IC (

Fraser et al., 2022;

Lønne et al., 2023). This leads to the assumption that while poor design may demotivate engagement, overall, instructional methods are not a key factor for success. However, other factors such as ethnicity did not influence learners’ IC levels either.

The qualitative interviews provided some insight into the learning experiences and possibly explained the positive shift in PSTs’ IC. Both platforms presented technical challenges that served as an opportunity for bonding and solidarity. These demonstrations of kindness, generosity and support among group members exemplify two stages in Kolb’s cycle (

Kolb, 1984). First, through these challenges, individuals experienced the ‘reflective observation’ where peers could see themselves in the struggles of the other which then evolved into the second stage of ‘abstract conceptualizations’ where students could demonstrate empathy, patience, and openness by offering support to their peers. According to these observations, technology is not only a “facilitating tool” of intercultural encounters, but a dynamic variable that shapes cross-cultural relationships by providing the space to exhibit empathy and collaborative problem-solving, key components of IC (

Savicki, 2023).

In these cases, learners demonstrated sensitivity and empathy for each other, and compassionately reached out, which are central characteristics of IC (

Pastori et al., 2018). However, students mentioned technical difficulties and incomplete or unclear courses and task instructions which challenged the learning experience and would require improvement for future programs.

Thus, while technological innovation enabled the project to take place, the glitches experienced by the VW group led to interesting and enlightening results. Although clearly these technical difficulties challenged participants and created different degrees of frustration, some of which was reflected in some quantitative measures; these same obstacles created opportunities for collaboration, mutual support, and empathy—all qualities central to IC. Thus, technology simultaneously posed barriers and provided meaningful contexts for intercultural learning. The important understanding gleaned from this experience is that programs must include adequate technical training and that there is also a place for reframing challenges as opportunities for teamwork and intercultural growth.

The interview findings can be explained under Kolb’s experiential learning cycle (

Kolb, 1984) which posits that learning occurs through a process of four stages: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. The intercultural encounters created by both VW and Zoom provided participants with concrete experiences of diversity and collaboration. The challenges they faced, including technological barriers, language differences, and group coordination provided opportunities for reflective observation. This was particularly true when participants held discussions in peer groups or parallel channels such as WhatsApp. These deliberations facilitated abstract conceptualizations about the value of empathy, patience and openness toward others. Finally, participants described their intentions to carry forward these insights to their professional practice, which can be seen as corresponding to the active experimentation stage. This alignment with Kolb’s cycle underlines the fact that even seemingly modest survey-based improvements may reveal experiential transformations.

Empathy was also evident, as many PSTs mentioned the new level of open-mindedness and curiosity to further get to know each other, and even willingness to work together in the future. Positive and open attitudes are another key aspect of IC as they allows individuals to remain responsive and respectful to the surprises of cross-cultural interactions, making them harmonious and pleasant (

Deardorff, 2021). This positive attitude was demonstrated in other program challenges, such as language barriers or coordinating time for synchronous work. Students expressed frustration, but also willingness to cooperate towards a solution which is where the true nature of intercultural competence lies (

Deardorff, 2021;

Savicki, 2023). These findings also confirm that the chosen VW platforms successfully provided space for real and personal interaction, establishing interactive learning platforms’ potential as a space for social connection and collaboration.

Students confirmed that participating in virtual worlds created a strong sense of “presence”- the subjective feeling of being there (

Slater & Wilbur, 1997;

Lombard & Ditton, 1997), which stimulates engagement and relational responsiveness (

Slater & Sanchez-Vives, 2016) that the VW group also demonstrated. The students who took part in the virtual worlds in this research reported feeling that their interactions were more spontaneous and more emotionally expressive, as compared to those taking place over Zoom. However, qualitative results data did not confirm previous research narrative (

Fraser et al., 2022;

Lønne et al., 2023). This contradiction suggests that the feeling of “presence” alone is insufficient without fostering productive cross-cultural communication and collaboration. Thus, while technology helps facilitate these encounters, opportunities for solidarity and support, as seen above, can foster intercultural sensitivity and competence by encouraging friendly behaviors. Moreover, there is a need to further examine how cross-cultural communication quantity and quality across virtual platforms can affect IC development.

Importantly, interview data has shown that students in the VW research group had significantly more communication with their group members than those in the Zoom group, underlining the importance of VW for satisfaction in collaborative learning as was found in previous research (

Shonfeld, 2021). Concerning satisfaction with communication, the ethnicity influenced the satisfaction with communication within the group where Arab student reported on higher satisfaction. This could be attributed to the language barriers, internet networks and technological problems where group help and communication were crucial. Moreover, the VW group reported higher satisfaction with communication compared to the Zoom group. This is also because they had more technical problems with the VW and needed group assistance.

The discrepancy found between modest quantitative gains and rich qualitative accounts highlights the importance of methodological considerations. It underlined the fact that standard self-report surveys may not always detect subtle shifts in intercultural competence that manifest in moment-to-moment behaviors, such as showing patience when a peer struggles with technology or coordinating across linguistic differences. Qualitative interviews, by contrast, illuminated these micro-interactions, underscoring their importance in the development of IC.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to test whether active participation in immersive VW simulations would have a greater impact on pre-service teachers’ development of intercultural competence as opposed to passively observing the same activities via Zoom. Our findings show that, quantitatively, both platforms supported the expression of key IC characteristics, but the VW environment uniquely facilitated richer peer support, peer solidarity and empathy, key characteristics of IC.

The current research strengthens the place of virtual simulation learning activities as an effective and successful educational methodology to improve learners’ IC by offering a neutral and safe space for experimental and productive intercultural contact. VWs are particularly valuable in teacher education for modeling how educators can facilitate dialogue across cultural divides. This study has illustrated how technological interactions can form meaningful intercultural experiences through structured group tasks, guided reflection, and scaffolded discussions while technical or logistical challenges can be beneficial as opposed to counterproductive for intercultural growth.

Furthermore, teacher education programs can better prepare future educators for multicultural classrooms by integrating principles of experiential learning and designing environments that maximize presence. The findings suggest that such training programs would benefit from investing not only in subscription for platform access but also in training students to navigate technical challenges collaboratively, turning potential frustrations into opportunities for empathy, patience, and intercultural problem-solving.

The results indicate that intercultural simulations, regardless of platform, can serve as valuable pedagogical tools for fostering modest gains in IC. This establishes that platform choice for teacher training programs should also be guided by how well it supports reflection and scaffolding of intercultural learning. Thus, the choice of platform should be made with attention to trade-offs: VW can enhance empathy and satisfaction when technical conditions are well-supported, whereas Zoom offers a more accessible and stable environment with fewer usability challenges. The practical takeaway is that intercultural simulations may offer modest benefits regardless of platform; VW may enhance perceived communication satisfaction, but it can also introduce usability burdens that impede learning.

Some factors have been outlined as possible contributors to this change, such as cooperation in problem-solving. Moreover, the research demonstrates the advantages of using advanced technologies to improve intergroup relationships; while stressing the importance of teaching users to master those technologies so they can benefit from them and not find an additional obstacle in intergroup contact.

From a practical standpoint, the findings suggest that although the outcomes for VW and Zoom were broadly similar, it is reasonable to assume that initial technological challenges may have constrained the potential advantages of VW. The integration of structured technical training and early guidance could mitigate these barriers and establish conditions under which the immersive affordances of VW are more likely to manifest. With such provisions in place, teacher education programs would be better positioned to evaluate, and ultimately to strengthen, the contribution of VW to the development of intercultural competence

7. Future Research

This study leads to three main directions for future research. First, longitudinal designs should assess to what extent the observed improvements in IC are long-term, and how far they influence professional practice. Secondly, comparative studies should be set up across digital platforms to examine how varying levels of presence affect intercultural learning outcomes. Thirdly, it is important to understand how digital self-efficacy and pre-training impact learners’ ability to benefit from virtual intercultural encounters. Studies into technological preparedness could further refine best practices for integrating technology into intercultural education.

This research compared the results of simulation in 3D environments to a Zoom environment and video clips. The VW environment was difficult to navigate, and students were unable to be part of the simulation, so it was hard to compare the simulation influence. Thus, it is recommended to continue and follow this research with other virtual platforms that are user friendly and improve students’ experience.

This study demonstrated that virtual simulations can be effective for fostering IC in multicultural and conflictual contexts. Although quantitative results, while significant, were limited, the qualitative findings underscored important factors of experiential and relational growth. When viewed through the prism of Kolb’s experiential learning cycle and the construct of presence, the findings suggest that intercultural learning in digital environments is not only possible but can be transformative. With further refinement of technology and methodology, virtual platforms can play a vital role in advancing intercultural education and dialogue.

Future studies should test advanced VW technologies in more balanced group designs (Gender and Language) and continue to refine instruments that measure intercultural competence across diverse populations.

8. Study Limitations

Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, group sizes across conditions were imbalanced, and assignment was not random. Second, instructor effects may have influenced group dynamics due to variation in facilitation styles. Third, students entered the course with differing levels of familiarity with the VW and Zoom platforms, which may have affected their comfort and engagement. Fourth, the self-selection of the participants was based on their willingness and availability, and the researchers could not force them to participate and to randomly distribute them which caused ethnicity imbalance. Moreover, most of the participants were women since teacher education colleges attracts mostly females. Finally, questions remain unresolved regarding the measurement of the intercultural sensitivity across cultural groups.