Abstract

In health professions education, the hidden curriculum is a set of implicit rules and expectations about how clinicians act and what they value. In fields that are very homogenous, such as rehabilitation professions, these expectations may have outsized impacts on students from minoritized backgrounds. This qualitative study examined the hidden curriculum in rehabilitation graduate programs—speech-language pathology, occupational therapy, and physical therapy—through the perspectives and experiences of 21 students from minoritized backgrounds. Semi-structured interviews explored their experiences with their programs’ hidden curricula. These revealed expectations about ways of being, interacting, and relating. Three overarching themes emerged, each reflecting tensions between conflicting values: (i) blend in but stand out; (ii) success lies in individualism, while de-prioritizing the individual; and (iii) fix the field, using your identities as a tool. When the expectations aligned with students’ expectations for themselves, meeting them was a source of pride. However, when the social expectations clashed with their own culture, dis/ability, gender, or neurotype, these tensions became an additional cognitive burden, and they rarely received mentorship for navigating it. Health professions programs might benefit from fostering students’ critical reflection on their hidden curricula and their fields’ cultural norms to foster greater belonging, agency, and identity retention.

1. Introduction

Rehabilitation fields (e.g., physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech-language pathology) are facing a crisis of minoritized student recruitment, retention, and overall well-being. These issues have been linked to reduced feelings of belonging in their training programs (Knox-Kazimierczuk et al., 2024). Other health professions have found the “hidden curriculum” to be a powerful driver of students’ feelings of belonging in their fields or lack thereof (Hunter & Cook, 2018), and it has been implicated in students’ feelings of psychological safety (Torralba et al., 2020). The hidden curriculum refers to a collection of implicit, unspoken expectations for how students should behave, what they should believe, and what values they should hold (Gaufberg et al., 2010). It is the perpetuation of a culture and its norms. For example, the norms of “professionalism” are typically taught through the hidden curriculum, rather than through formal teaching (Azmand et al., 2018; Yahyavi et al., 2021). These expectations affect how new clinicians dress, speak, and carry themselves, as well as what they prioritize and value. Despite its expansive effects, though, the hidden curriculum is difficult to observe and critique because of its implicit nature. For example, educators often judge students’ professionalism against the norms that they themselves have observed, without critiquing the purpose or cultural context of those norms (Hodges et al., 2011).

The existence of a hidden curriculum is generally thought to be inevitable. When placed in a group, people naturally create cultural norms and expectations (Arrow & Burns, 2003). These typically stem from the individual members’ own shared social conventions and are difficult to disrupt (Hawkins et al., 2019). When these implicit expectations are placed in an educational setting, they are often discussed as “rules of the game” because the students are being critiqued on their ability to follow these rules, even if they were never explicitly taught (P. Jackson, 1968; Hill et al., 2014; Jack, 2016; Laiduc & Covarrubias, 2022). Students’ ability to follow the “rules” are linked to their success in the educational and clinical settings (Hill et al., 2014; Jack, 2016; Laiduc & Covarrubias, 2022). As students enter healthcare programs, if they already share sociocultural backgrounds with the majority of the program, they may not notice these rules at all because they have already been socialized into them (Laiduc & Covarrubias, 2022). However, students whose sociocultural backgrounds do not align with the majority culture are expected to follow rules they have not already been implicitly enculturated into. They are therefore set at a disadvantage and may be perceived as deficient, incapable, or disengaged when their behavior does not align with programmatic norms (Delpit, 1995; Laiduc & Covarrubias, 2022; Valencia, 2010).

1.1. Programmatic Norms in Health Professions Programs

There are clear advantages to having a healthcare workforce that mirrors the identities of their patients. A wealth of studies indicate that when clinicians and patients have shared backgrounds, clinical outcomes improve. Shared backgrounds have been linked to more patient-centered care (Cooper et al., 2003; Shen et al., 2018), better clinical outcomes (Takeshita et al., 2020), lower healthcare costs (Jetty et al., 2022), increased follow-through on clinical recommendations (Jetty et al., 2022; Traylor et al., 2010), and improved patient satisfaction (Cooper et al., 2003; Saha & Beach, 2020). These benefits are not just about looking alike. When clinicians and patients have shared values, experiences, and understandings of the world, it allows patients to feel heard and become partners in their own care (Shen et al., 2018). Patient-centered healthcare requires effective communication between patient and provider, and language and cultural barriers can impair health outcomes (Genoff et al., 2016; Yeheskel & Rawal, 2019). In addition to better understanding their patients’ perspectives, healthcare providers from minoritized backgrounds are more likely to work in underserved communities and areas with high proportions of patients from minoritized backgrounds (Salhi et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2009). These benefits drive the recruitment and training of a diverse healthcare workforce.

Despite efforts to develop a representative rehabilitation workforce (Davis et al., 2025; Guiberson & Vigil, 2021; Olson & Burks, 2022), the fields themselves remain overwhelmingly White and less diverse than the general population in the United States. Although 44.3% of the population identifies as a racial group other than non-Hispanic White, a report from the Health Resources and Services Administration released in 2024 revealed that the physical therapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT), and speech-language pathology (SLP) professions remain homogenous, with between 20 and 27% of their workforces identifying as non-Hispanic White (HRSA Health Workforce, 2024). Educators in rehabilitation fields appear to be even less diverse. While such numbers are not available for entry-level SLP programs, in 2023, only 16.5% of faculty in PT programs and 19% of faculty in OT programs identified as being from racially/ethnically minoritized groups.

1.2. Clinical Identity Development Through Social Learning

The present study is grounded in social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), which asserts that learning is inextricably linked with its social context, which includes how one’s own behavior influences their social relationships and learning from others’ experiences. Social learning theory has underpinned many discussions of clinical identity development (e.g., Cruess et al., 2019; Holden et al., 2012; Horsburgh & Ippolito, 2018; Sheehan & Wilkinson, 2022). These authors posit that student clinicians become socialized into their new clinical identity through watching and interacting with their peers, professors, and other role models. Students learn how a PT, OT, or SLP behaves; what they value; how they speak; and other subtle social-cultural norms through interactions with their social environment.

Social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) sets the groundwork for how students learn these social expectations, and the hidden curriculum describes what the expectations are. Since rehabilitation clinicians and educators are overwhelmingly from majority groups, it is likely that the implicit social expectations of the hidden curriculum are also based on majority cultures. As sociologist and social identity scholar Miller (2022) describes, majority norms are often so pervasive that people who are already socialized into the culture often do not notice these norms exist. However, she notes, “although pervasive, these standards are far from neutral” (p. 5). Perpetuation of these norms prioritize students who are already socialized into them and who easily align with them (e.g., having few needs that would inconvenience the status quo).

While the nature of the hidden curriculum has been studied in medical students (e.g., Armas-Neira et al., 2024; Behmanesh et al., 2025; Hafferty et al., 2015; Hill et al., 2014; Lempp & Seale, 2004; Neve & Collett, 2018), it has not been studied in rehabilitation professions programs. This is of particular import because rehabilitation professions are even less diverse than medicine in the United States (United States Census Bureau, 2024), and these practitioners often have lengthier clinical encounters with their patients. Thus, the positive impacts of shared identity may be magnified in rehabilitation work, making developing a rehabilitation workforce that mirrors its clients all the more important. If rehabilitation profession programs are to be successful in recruiting and retaining students from a diversity of backgrounds, they must be aware of their programmatic culture and how it impacts these students. Students whose cultural or personal experiences do not align with the majority of the program may be more keenly aware of the social norms and expectations of the program and how they do or do not fit within them. This hidden curriculum may affect how they learn in their programs, how they develop professional identities, and whether they feel they belong in their chosen fields.

This qualitative study sought to understand the hidden curriculum of rehabilitation programs through the perspectives and experiences of students from minoritized backgrounds. We believed that PT, OT, and SLP students might share a hidden curriculum as they often practice and learn collaboratively (Ikeda & Sasada, 2022; Schwab-Farrell et al., 2024). This has led to a growing body of literature on how these students develop interprofessional identities (Khalili et al., 2013; Plummer & Naidoo, 2023). Through individual, semi-structured interviews, we sought to answer the questions: What social messages do PT, OT, and SLP programs send about how to be successful in the program and the field, and how are they conveyed?

2. Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the MGH Institute of Health Professions Institutional Review Board (#2024P000172).

2.1. Recruitment and Sampling Methodology

Participants were recruited using convenience and snowball sampling approaches. The research team emailed recruitment flyers to graduate program directors of PT, OT, and SLP programs across the United States, requesting that they send the recruitment materials to their students. In addition, the flyer was posted on online Facebook groups for each profession. Participants were also requested to share the recruitment link with others they knew from minoritized backgrounds. Participants were monetarily compensated for participating in the interview.

Participants were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: over the age of 18 and a current graduate student or had graduated/exited from an entry-level PT, OT, or SLP program in the past two years in the United States. Participants also needed to identify with at least one minoritized identity in the United States, including but not limited to racial and/or ethnic minority, gender and/or sexual minority, disability, neurodiversity, linguistic minority identities, or first-generation college student. To ensure that participants had some experience with their programs’ cultures, students were excluded if they were within their first 3 months of their graduate programs. Additionally, since the interviewers included two SLP faculty members, individuals were excluded if they attended the SLP program at the researchers’ university.

To schedule interviews, participants were directed to an informational website with positionality statements and photos of each interviewer. They discussed their disparate racial, ethnic, sexuality, and dis/ability identities, as well as their fields and positionality to the work. Using Microsoft Bookings, participants chose a member of the interview team to schedule with. This scheduling strategy was chosen to increase the likelihood they would feel comfortable discussing issues of identity and belonging with their interviewer. Participants also completed a preliminary questionnaire that included inclusion criteria, demographic information, and their impressions of their programs’ demographics. Participants also created their own pseudonyms.

2.2. Participants

There were 21 participants, 7 from each field. Throughout the manuscript, participants are referred to by their chosen pseudonym and pronouns. Due to the low numbers of minoritized students in these programs and the intersecting identities of each participant, providing individual demographic information for each participant could risk their anonymity. Therefore, demographics are presented in Table 1 in aggregate.

Table 1.

Participant self-described identities, in aggregate.

2.3. Interview Structure

The semi-interviews were conducted over a secure Zoom client. The interview transcripts were manually corrected using the audio recordings. Participants were asked about the demographics of their programs, its ideas of professionalism, what the program valued in its students, and their feelings of belonging within the program and the field. Questions were adapted from Lempp and Seale (2004), Bandini et al. (2017), and Gupta et al. (2020). A copy of the unannotated semi-structured interview script is available as Appendix A. As is the nature of semi-structured interviews, the interview team used the script as a guide but asked participants follow-up questions as seemed relevant, to encourage a fuller picture of their experience and opinions.

Prior to conducting the first interviews, the interview team piloted the interview script with four clinicians (2 SLP, 1 PT, and 1 OT), who provided feedback on the questions and the way the interview was presented. The team adjusted and annotated the questions based on their feedback. These pilot interviews were conducted until the interviewers felt confident in their ability to be consistent with one another and to encourage meaningful stories from the participants.

2.4. Coding Methodology

The initial coding was conducted by at least two coders throughout the data collection process to assess for meaning saturation, using a constant-comparative method (Glaser, 1965). First, the research team each individually coded two interviews. They then met to develop the initial code book. A team of eight coders (two faculty from the research team and six students from minoritized backgrounds) then coded five more interviews using Dedoose qualitative coding software (Version 10.2.25). This coding group was chosen to ensure that the student perspective was represented during the coding process. Students coded in pairs, and faculty coded individually. Each pair/individual coded a different interview. Each researcher developed their own set of themes and shared their work, and then the group agreed on one set of themes. The coding team met to discuss and revise the code book. They then re-coded their interview and coded a new interview. The team met two more times to add new codes or change definitions within the code book, re-coding the interviews after each meeting. The code book was revised twice until meaning saturation was reached.

Post hoc coding of the interviews allowed the research team to assess for meaning saturation: a point where no new codes were emerging from the data and the codes’ meanings were not shifting definitionally, expanded conceptually, or generally changing in meaning as more examples arose with coding (Hennink et al., 2017). After the initial 16 participants’ interviews went through each step of the coding process, the team believed that meaning saturation had been reached. Five additional participants’ interviews were coded to assess for meaning saturation. No new codes arose during this process, and only one code was conceptually adjusted to include an additional example. Saturation was determined to be reached. These additional participants were included in the full count, bringing the total to 21.

2.5. Trustworthiness

To align with the pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research (Ahmed, 2024), the researchers leveraged researcher and data triangulation, an audit trail, member checking, and thick description for increased transferability of findings. Researcher triangulation included eight coders coding independently (or in pairs) and then meeting to achieve intercoder agreement. All research materials were kept in a central location, which produced an audit trail that allowed for the study process to be replicated. Researchers also reached out to participants whose quotes were utilized in the paper to ensure their words were being contextualized accurately. Rehabilitation program students from minoritized backgrounds were included in the code development and coding process. The researchers acknowledged their roles as research instruments in the data analysis process and that their subjectivity and emotion influenced the data analysis and results. The faculty researchers’ positionality statements are available in Appendix B.

3. Results

A total of 54 codes were generated from the interviews. Although the stories that revealed the hidden curriculum differed somewhat from field to field, the overarching nature of the hidden curriculum spanned all three fields. All codes were shared across fields. The codes described ways of being (e.g., be a bubbly extrovert and be calm and knowledgeable), ways of interacting with the program (e.g., prioritize school over self or outside life and be around as much as possible), and ways of relating (e.g., find your people and success comes from being liked). They also discussed actions and activities that were prioritized in the programs, such as build rapport with clients, speak up in class (non-critically), and do not expect flexibility in the “real world”. An additional 12 codes were created that described where the lessons came from, such as written expectations, the culture of the cohort, and how the learning environment is set up.

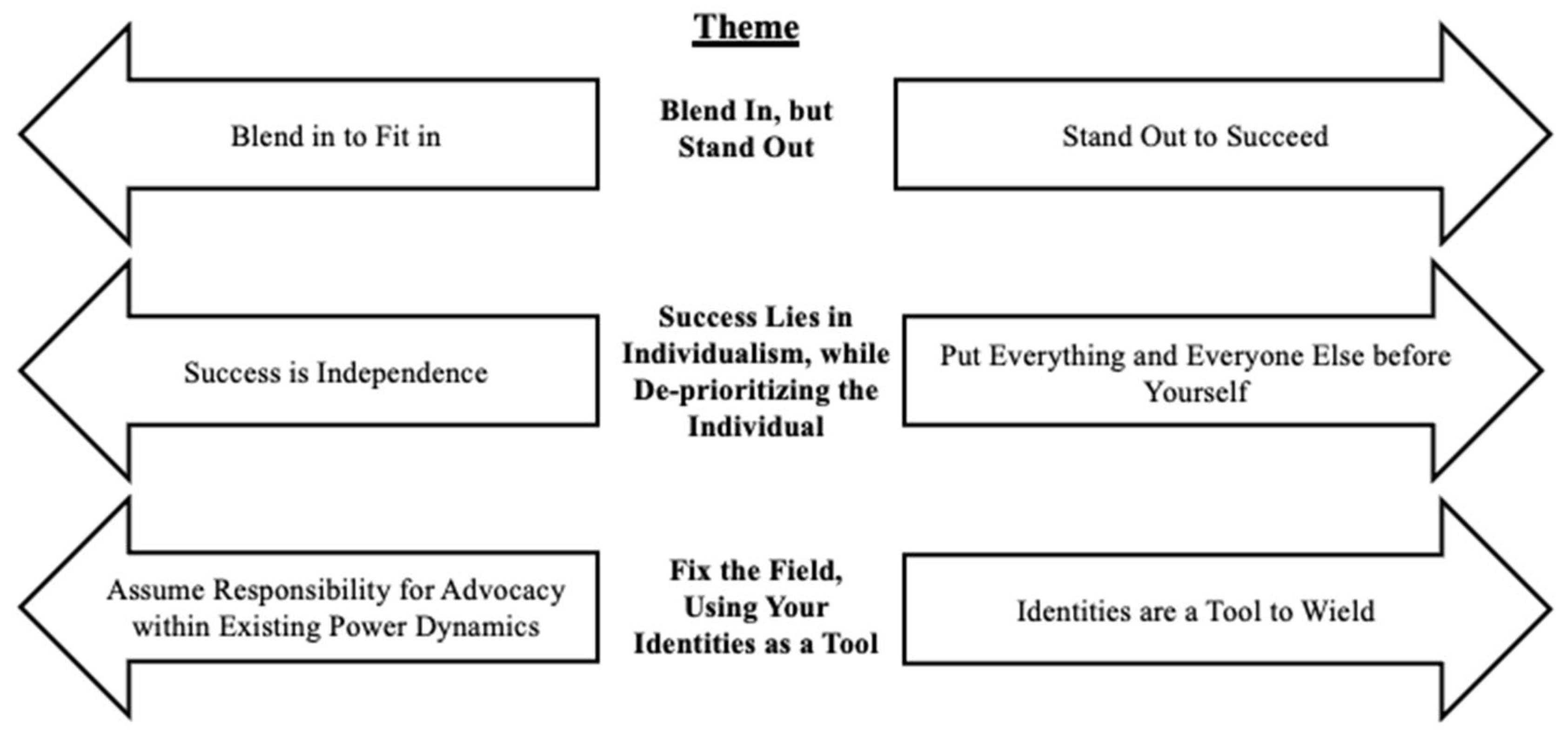

Across the interviews, the overarching feeling was one of tension between conflicting values and expectations. Three themes arose from the codes, each of which spoke to a tension between two or more conflicting values, described herein as a subtheme. These themes and subthemes described how students were expected to relate to one another, the faculty, their clients, and the field. Although we expected to find separate categories of social and academic expectations, the participants’ experiences commonly blended the two together. An illustration of the tension inherent in each theme is available in Figure 1. This section will describe the three themes, as well as how graduate programs conveyed these lessons.

Figure 1.

Themes and subthemes of the hidden curriculum.

3.1. Theme: Blend In, but Stand Out

This theme describes the importance of fitting in with the graduate program’s social norms while also differentiating oneself if one wants to be classified as a “good student”. Fitting in with the social norms of the field and program was a common topic of discussion. These norms were linked to personality (e.g., be a bubbly extrovert and be a perfectionist) and ways of presenting oneself (e.g., speak professionally and be proactive, ambitious, high work-ethic). They also discussed minimizing parts of themselves that did not align with the norms of the field (e.g., act neurotypical and do not bring up individual needs). The codes and definitions within each subtheme are presented in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

“Blend in but stand out” codes and definitions by subtheme.

Participants often described a level of heightened self-monitoring in order to fit in with their classmates, often linking this to their minoritized identities. The individual traits and actions that participants described as prioritized (e.g., be loud and confident about trying, even if you fail) were not inherently linked to one particular culture or background. However, participants did not feel this need for self-monitoring was experienced similarly by their classmates from backgrounds that aligned with program majority. Participants typically believed that these students did not experience the same level of self-monitoring or self-censorship.

3.1.1. Subtheme: Blend In to Fit In

Participants described numerous pressures that led them to feel they needed to conform. Some discussed an implicit understanding that conforming to group norms is necessary for survival, and it is emotionally taxing to be different. These students often described the homogeneity of the students and faculty in their program and the need to conceal aspects of themselves to reduce the likelihood of rejection. Messages from faculty that one’s graduate school classmates would be their friends and trusted colleagues for life seemed to amplify this stress.

One way a student could blend in or stand out was by demonstrating relationality—easily entering into relationships with others. This included codes like be a good listener, be receptive to feedback, and be kind. Participants across disciplines discussed relationality as a cornerstone of their programs and fields. Many participants discussed traits like kindness and being a good listener as the assumed moral foundation of their fields. Yet, demonstrating kindness was not sufficient to blend in. As Samora, an OT student, noted, “you can be a caring person, but then have all these like unwritten rules.”

It was important not just to create these relationships but also to demonstrate this ability to faculty and peers. While programs encouraged cultivating the ability to form relationships with clients (build rapport with clients), they often appeared to view students’ ability to fit in with their classmates as a stand-in for their ability to do so with clients. Multiple participants described how faculty members stressed the importance of socializing with their peer groups. Alina, a Black female SLP student, described feeling socially removed from her predominantly White cohort. Although she was very participatory in class, she described being admonished by her professor for not being sufficiently engaged with peer socialization outside of class time. She noted,

I wasn’t well, the times that I was around [my classmates], because my mindset is different, especially as a person of color. Because, like, I was raised in a different environment to where, like in my life, experiences have made me see things differently… I’m not even having a space at the table. I will either sit in the very front or the very back, and they would talk about the same things. Like about someone’s wedding or traveling and things that. Like it gets old after you talk about it after a certain amount of time. So, then I would take these little breaks because I can get overwhelmed with social interactions at times, especially if we’re all together all the time. And so I would just be on my phone for like a quick second. But everybody was on their phone, and the comment that I got was— She was like one of my supervisors. She said, “Oh that phone! You’re on your phone. And, like you had so many opportunities to engage in a conversation.”

There were also educational incentives for fitting in. Many participants described having a peer group in the program as being important for class activities and clinical practice opportunities. PT and OT participants discussed how practicing physical manipulations in class was more comfortable when they were friendly with their peers, and social isolation meant having no one to practice with in class or as homework. Mona, an OT, described a homework format that occurred throughout the program where she needed to videotape herself practicing on another person. However, she was socially isolated from her classmates and in a new city. She had no one with whom to make these videos. She described her feelings:

So that makes me feel a lot more isolated. And sometimes they’re like, “oh, you could just use a teacher.” … Sometimes I was like talking to someone— like dating someone— and I’d just use them. But like, I’m not always like talking to someone, and it’s like it sucks. ‘Cause I know someone was like,“Oh, yeah, just like, go on Bumble, find someone.” Just like, why do I have to do this? … This is really making me really regret moving across the country.

In this way, being liked and fitting in with classmates were mediating factors to students’ access to learning opportunities and perceived success in the program.

3.1.2. Subtheme: Stand Out to Succeed

Participants also described the importance of standing out amongst the crowd. This sub-theme often arose in discussions of how to succeed and be a “rising star” in the department. Standing out was therefore a way to thrive and be acknowledged as successful in the department. This subtheme included such codes as be a leader, demonstrate admiration to faculty and staff, receive high grades, and speak up in class (non-critically). Participants discussed the importance of being the person who asked and answered questions in class, creating relationships with faculty outside of the classroom, and generally volunteered. Samora, OT, discussed how being active in the classroom and talking to the faculty outside of class was rewarded with coveted clinical placements:

If you speak up, if you’re active in the community, and if you kind of like make yourself known, you know, like … take initiative early to like, talk to faculty, and … talk about to them about clinical placements that you’re interested in, that that could be rewarded like with the things that you want. Like the internships that you want.

While, at face value, this subtheme may appear to conflict with the pressures to blend in, blending in was often required before one could stand out. When described positively, “standing out” only occurred in very prescriptive ways. Students were encouraged to ask non-critical questions about course material, although questions that were interpreted as critiques were punished. They were encouraged to be loud and confident about trying (even if they failed) but also to be a perfectionist and avoid being the weak link in the group. Therefore, one could stand out only if they were blending in with social norms in doing so.

For some participants, the expectation to be vocally engaged in class felt comforting. Some described how this expectation aligned with their own culture or expectations for themselves. Multiple participants interpreted being vocal in their learning and seeking out the professors as being an inherent part of caring about their education. This was particularly notable in students who came to their program as a second career; they often described this overtness as a part of their conception of professionalism. Sam, PT, described this overtness as a part of her ability to demonstrate good bedside manner, for which she has been praised by instructors and peers:

I got [feedback] consistently was that I was really good at kind of communicating with coworkers, and being very professional.

Others discussed how the overt expectation to be vocal and participatory pushed them to engage with class in a way that was important to their growth. Still others described how, although there was pressure to make sure their classmates and educators saw they were trying, it was less overt than they had experienced in their undergraduate programs. One PT, Landon, noted that although there was an expectation to stand out, it did not accompany a requirement to compete with other students for faculty’s attention or the best grades. This felt freeing to him in comparison with his undergraduate experience. As he noted,

Because there weren’t many like awards or positive things that people, you know, had to compete for… I think that was a key point for me helping to feel like, okay, you know, I can do this. Right? I can belong here, both academically and socially, with friends.

Still others found the expectation to stand out to be off-putting and in direct contrast to their sociocultural expectations for their own behavior. Many described how their quiet participation due to nervousness or their own learning style was interpreted by instructors as not caring, not being engaged, or not being prepared. Participants described holding these clashing expectations for themselves as a cognitive burden. Samora, an Asian OT, described herself as a quieter person who made herself speak more often and more loudly than her personality or culture would dictate because of this expectation. She described her constant vigilance about how she was either confirming or negating Asian stereotypes:

I think it’s just that unwritten rule, you know: being loud and stating your opinion, I have to make sure…as an Asian person who is stereotyped for being like on the quieter side, I have to like break that stereotype-kind-of-thing to do well. But sometimes, you know, I don’t want to have to talk loudly or anything like that. I have to tell myself it’s okay that I don’t want to do that… I’m not like being the stereotype by not following that rule. But it’s hard… I think, in order to do well, you have to follow the rules … [by] not following the rules, like you feel like you’re reinforcing a stereotype, which is, it feels like a weird cycle.

While Alina, a Black SLP, described the risk of being stereotyped as aggressive when advocating for herself:

In my program, when I was extremely vocal and self-advocating for myself, it was deemed as me being aggressive, or “she’s doing too much”… But when I went to study abroad and I was quiet, I didn’t talk about all the things I usually talked about. They told me that it’s ruining my professional brand and how I need to really engage more in the culture that I was surrounded in, which is the white culture in my classroom, and I was very confused. Because I’m like, if I talk too much, I’m aggressive or deemed as being too much? But if I’m too quiet, you have a problem with that, too?

3.2. Theme: Success Lies in Individualism, While De-Prioritizing the Individual

This theme spoke to the importance of prioritizing others’ needs above one’s own. Part of this included demonstrating independence within the existing system. “Independence” in this context includes the ability to achieve high grades on assignments, complete clinical activities, and know what to do without being perceived as having many needs of their own. This aligned with an expectation to de-prioritize the student’s own needs and community ties. The codes and definitions within this theme are presented in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

“Success lies in individualism, while de-prioritizing the individual” codes and definitions by subtheme.

3.2.1. Subtheme: Success Is Independence

This subtheme was tied to students’ ability to master the coursework and clinical skills without requiring much guidance. Participants’ judgements of what constituted requiring “too much” guidance often differed. Attempting to figure out where this line lay was a source of stress. While some students described the importance of attaining independence gradually, others discussed the importance of finding the curriculum to be simple on the first try. This subtheme included codes such as be a perfectionist, be over-prepared, overcome your disability, and don’t expect flexibility in the “real world”.

Jasmine, SLP, had sustained a brain injury many years prior to starting her master’s program. She was constantly aware that she needed to ask questions and request appropriate accommodations to learn. Yet, she felt that each request came at the cost of her reputation as a competent student. As she noted,

I think “success” was like being able to do all of work, no problem. Right? Not bugging a lot of the professors… It was just that they were willing to answer questions as long as they weren’t too long, as long as they didn’t require an in-depth answer. And I’m a person who talks aloud a lot to understand things and to like, remember things. … I think, as a student, when you ask for certain like accommodations or like extras, right? You’re asking for more of your professors or faculty’s time, right? And it’s always really up to the faculty whether or not they will give you that extra time. … Asking for that you know, for those accommodations, like for certain professors kind of put me a little bit lower … in certain professors’ eyes.

3.2.2. Subtheme: Put Everything and Everyone Else Before Yourself

Participants also described programs’ expectations that they would prioritize their program’s and their clients’ needs above their own. This included codes like, drop everything for school, be around as much as possible, and do not bring up individual needs. Participants discussed programs’ expectations that students would accommodate last-minute schedule changes, which was difficult for students who had jobs, caregiving responsibilities, or a substantial commute. Many described needing to juggle home life with their program’s expectation that they would volunteer for extracurricular assignments and be physically available on campus. For students who were local and had established community and family nearby, this was an implicit message to weaken their ties with their responsibilities and community to prioritize the program’s needs. Landon, PT, described,

I feel like there is an expectation to kind-of drop everything for the program… They’d let you know what like days we have class and what to prepare for two weeks before it. … If you want to hold a job like part time through grad school, just find a flexible job, right? That’s gonna be hard because you don’t know what your class schedule will be like.

Participants experienced this implicit pressure to divest themselves of their community ties and personal needs as one to put themselves and their own needs last. They often described instances where faculty were hesitant to accommodate individual circumstances outside of disability accommodations. One Muslim participant described needing to be careful about asking for too many religious holidays because a professor had implied she was a nuisance. A transgender participant was required to allow their peers to touch them during in-class practice, despite being frequently misgendered. They had to seek a disability diagnosis to be allowed to choose their own partners. As they described,

I had to get formally diagnosed with ADHD and autism in order to get accommodations for being trans.

This was compounded by concerns that when students did advocate for themselves, they experienced retaliation. At times, the retaliation was subtle, such as a shift in the relationship between the student and faculty member. Other times, it was more overt, such as being required to do extra work or losing access to educational opportunities. One participant with post-traumatic stress disorder described being removed from a school-based clinical placement after asking to be warned about active shooter drills and fire alarms. She noted,

They were like, “Oh, well, should you fail clinic now, because you were taken out?” That was a discussion. … I had reached out to my program for support… I tried to do the avenues they tell us to do: reach out to the clinical coordinator. And I felt like they just made me feel like I’m a problem, and you know “too much”. Like actually said that.

Jamie, PT, described how retaliation in a clinical placement made her reluctant to discuss any other issues throughout the program:

But I think that the unwritten rule would be to just be quiet, like to keep your head down a little bit more. I think that you might get further that way unless something really is of great dire issue to your health, or you feel like you’re not going to be able to complete the program unless this happens, like I don’t think some-- Some things are not worth bringing up.

3.3. Theme: Fix the Field, Using Your Identities as a Tool

This theme spoke to an implied responsibility for students with minoritized identities to make their field more inclusive, while wielding their identities as a tool. Codes included expectations of action (e.g., teach the class/faculty about your identities, advocate for yourself, be happy to be a token representative) and resisting action (e.g., don’t argue back, don’t assimilate). The codes and definitions within this theme are presented in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

“Fix the field, using your identities as a tool” codes and definitions by subtheme.

3.3.1. Subtheme: Assume Responsibility for Advocacy Within Existing Power Dynamics

Participants described being expected to learn how to advocate for themselves and their clients. They also described pressures from their programs to advocate for diversity-affirming practices. Although they did not typically receive guidance or mentorship on how to engage in this advocacy, they were often rebuked if they went about it in a way that faculty perceived as inappropriate or overly critical. Students were expected to be vocal advocates for their own needs but balance that with respecting the existing power dynamics and managing faculty/staff emotions.

Gus, a transgender PT student, noted that his program expected “excellence” in their students’ flexibility and ability to learn new information. However, he noted that the faculty expected him to be endlessly patient when they had difficulty understanding his gender identity:

Excellence in like the faculty … wasn’t expected in the same way when it approached respecting my pronouns or my bodily autonomy

Similarly, Samora (OT) described being an active member of her school community and having faculty ask her to attend events to represent the school. Yet the same faculty also still confused her with other racialized students, even after 3 years in the program:

We’re under 40 students… And you tell us that we’re going to be future colleagues… if you say that you respect me for the work that I’ve done at school, and like, you know, you asked me to go to these like events for you. Why can’t you like learn my name? I think that’s a big thing.

Leila, a Middle-Eastern SLP, experienced multiple racialized microaggressions from a professor. She described the cognitive burden associated with balancing her need for self-advocacy with consideration of the existing power dynamics:

I’m super respectful of everyone in the department, but I wouldn’t want anything to come off disrespectful to my peers. And then I’m all about the constructive criticism to everyone. But it’s a very weird position to be in, because like—it’s just not my job [to fix the programmatic culture], and I don’t know how else to say it. And it’s very frustrating, because I feel like, if it’s not my job, whose job is it? Like, how is this program, how’s this field, how— how is anything going to get better if I’m just saying “it’s not my job”? But then I also think, like, all of my peers don’t have to deal with this and… like I have so many things due tomorrow. And why am I spending 2 h thinking about this?

3.3.2. Subtheme: Identities Are a Tool to Wield

Participants frequently described realizing their programs saw their identities as skills or tools. Ashley, a Vietnamese SLP, described a disconnect between how classmates and professors talked about her bilingualism and the way she experienced it. Her program conceptualized her bilingualism as a convenient trait that would make her more marketable, while she saw her bilingualism as an intrinsic part of who she was and part of her culture—a culture that she otherwise felt was critiqued in her program. She described the following interaction with her professor:

[My professor] was talking about how I put ‘Vietnamese fluent’ in my resume, and she’s like … That’s like your selling point, and you should let them know first off, like, “Oh, you’re bilingual, and that’s like a high need.” I feel like that’s like the only time so far [in the program] that I’ve like authentically addressed my like bilingualism and identity … I feel like it should be more like more occurring to be proud of who you are, identity-wise, beyond just race or ethnicity.

Participants felt this experience was unique to students from minoritized backgrounds. They did not believe that those from majority cultures received similar messages to use their identities as a tool. Bilingualism, specifically, was often positioned as an asset to the field, but the associated culture was positioned as a liability. Having a non-majority culture was often only an asset if the student was able to fully align with clients from the majority culture and also seamlessly world-travel (Lugones, 1987) between their culture and the majority culture.

When such world-traveling was easy or natural to them, participants often did not experience this dynamic as a stressor. Some felt proud of their ability to culture-shift and excited to use their experience as a minoritized student to increase representation in their field. Cheyna, PT, described using her cultural knowledge as an African American woman to educate her classmates about her community when she felt her program was falling short:

It’s important for [PT students] to know how to treat African Americans and people of color, because this is what happened: we touched on it in in this one class. But how would [students know how to] react in these situations? … So let’s interact. Let’s do some interactions and see how you will react because I’m gonna act like how my grandma will act or somebody else’s grandmother. And the moment you disrespect them, you need to know you’re going to have a lawsuit on your hands.

Landon, PT, described being expected to change the way he spoke to be considered professional. He appreciated learning how to make this switch and felt it was an important part of learning to be a clinician:

I have to respect [the program’s culture] so it can deem me worthy of being here, so to speak… Okay [I] need to be on my best behavior, and I need to speak just the best way, even if it means, you know, speaking in a different way. … I definitely there was like certain reverence to it.

For others, this world-traveling came at more of a cost. They discussed feeling like they never quite belonged or needed to conceal their identities in their programs. Holly, a bisexual SLP whose girlfriend was also in her cohort, described the emotional toll of hiding their relationship from their program:

I can’t be fully myself in grad classes, as well as like in clinical placements. And so it’s hard to find that connection and that sense of belonging when you’re not actually fully being you.

3.4. How Lessons Are Conveyed

There were 11 codes for how students learned about the hidden curriculum. These messages were conveyed implicitly (e.g., how the learning environment is set up, watching what others do) and explicitly (e.g., written expectations, being rewarded/watching others be rewarded, peer acceptance/ostracization). Students also arrived at their programs expecting a certain culture. These expectations were based on their own experiences with higher education environments, their culture, and what others had told them about graduate school. Therefore, some of the messages of the hidden curriculum were bound up with students’ cultural expectations, leading to such codes as I just know, prior experience, and it’s how I was raised. The codes are available in Table 5 below, separated by programmatic messages and individual expectations.

Table 5.

“How lessons are conveyed” codes and definitions.

Their expectations were either confirmed or revised based on experiences in the program. Graduate programs were therefore continually either confirming or refuting students’ expectations for how they should act, how they should advocate, and how they would fit within the program or the field.

4. Discussion

We sought to examine what social messages health professions programs sent to students about how to be successful in their programs and fields and how they were conveyed. We anticipated that the hidden curriculum would be shared amongst these rehabilitation fields, which was borne out in the interviews. While the nuances of how some codes were experienced differed between fields, there were no codes that were field-specific. For example, while all professions discussed word choice in the code speak professionally, SLP occasionally also included a focus on adjusting accent to align closer to a standard American accent, which participants aligned with the concept of being a professional. All professions described the “norm” of the profession as White, female, and non-disabled American; however, PT students in this study also saw someone as “athletic” as representing the “norm” of the profession.

Our interviews revealed the implicit tensions in the hidden curriculum of rehabilitation profession programs. Students were expected to hold conflicting expectations for their own behavior. At times, the hidden curriculum aligned with participants’ own understandings of what they expected from themselves. When this occurred, participants often described pride in their ability to conform or excel within the bounds of the expectation. In these situations, participants sometimes felt their minoritized identities gave them an extra advantage: perspectives or skills that not all their classmates shared. This view of diversity is not uncommon in US cultures, where minoritized identities are often discussed as assets that can be “acquired and consumed” (Laiduc et al., 2024, p. 313) by organizations. In doing so, this discussion divests people’s diverse identities from their positioning as an intrinsic part of the person, shaped by and interwoven within their lived experience. Diversity becomes a tool to wield or a card to play, an item separate from the self. Participants who felt at home with the tensions of the hidden curriculum commonly discussed the experience of having this extra tool within their minoritized identities.

However, when these expectations conflicted with participants’ own understanding of themselves, their cultural norms, or their needs, participants described the discomfort of needing to choose what to prioritize. Often, this led to navigating uncomfortable interpersonal dynamics on their own, with minimal guidance or support. This included interactions with peers, faculty, and clinical preceptors. Many students were concerned about social ostracization or removal from educational opportunities. They acknowledged that how faculty and peers perceived them could substantially impact their future careers.

This context often led students to be hyper-vigilant about their own behavior and how it did or did not conform to the expectations of their faculty. This constant vigilance is described in minority stress theory as “proximal minority stress”: the taxing internal stressors that come from experiencing discrimination, such as constantly monitoring for threats, monitoring one’s own behavior, and grappling with negative internalized messages about one’s identity or belonging (Meyer, 2003). One aspect of minority stress noted in the interviews was stereotype threat: the participant’s awareness that they risk confirming known stereotypes about their identities (Steele & Aronson, 1995). Participants described how stereotype threat affected how they chose to act in their programs, knowing they were one of few people with the relevant identity. They did not believe that students from majority backgrounds experienced this extra cognitive load, and they did not appear to believe that faculty were usually aware of it either.

4.1. Alignment with Majority Cultures

Many of the aspects of the hidden curriculum revealed in this study aligned with dominant United States cultural values, including the focus on independence and individualism; not providing space for minoritized people to discuss or act on how their identities impact their experience in the program; and an emphasis on a linear orientation of time that delays gratification, emphasizes planning for the future, and views time as a commodity (Miller, 2022, pp. 9–10). These priorities and ideals are culture-bound. As Miller (2022) notes, they lie in conflict with cultures that have a more fluid concept of time or prioritize community over individualism. Within the rehabilitation professions’ hidden curriculum, these values are apparent in the expectations for students to be independent and to put their own needs outside of the program on hold until they graduate. More specifically, White et al. (2024) describe the expectations to fit in by being considered moldable, “nice”, and not speaking up about one’s needs or disagreements as being specifically aligned with White female culture. This feminized expectation aligns with the majority-female demographics of the PT, OT, and SLP fields. This particular performance of “niceness” is not always accessible or culturally appropriate for people from other racial or gender backgrounds. Participants in the current study described how their intersecting race and gender identities resulted in stereotyping, even when they felt they were being kind and engaged learners.

These expectations prioritize a certain type of individual: one who is non-disabled, is financially stable, and has few responsibilities or connections outside of the program. It also prioritizes students whose social behaviors are aligned with the majority culture, reinforcing already unequal power dynamics. Students who already fit this mold might never notice that the hidden curriculum exists. In this study, when participants aligned with an aspect of the hidden curriculum, they often did not appear to recognize that there might be another way. Miller (2022) describes this as cultural hegemony: the idea that cultural expectations stemming from the majority culture are pervasive and often uncritiqued in United States cultures. Participants often only noticed these values when they conflicted with their own needs or expectations for themselves.

4.2. Social Learning of Programmatic Values

In this study, many of the values conveyed in the hidden curriculum were positive. It conveyed that kindness, prioritizing patient/client needs, and being a good listener were inherent to the moral foundations of the fields. Students learned that being participatory in class and engaging with the curriculum was good for their professional growth. In some ways, the hidden curriculum humanized the rehabilitation sciences, and there were benefits to the students’ development consistent with prior explorations of the hidden curriculum in medical school (Almairi et al., 2021; Behmanesh et al., 2025; Neve & Collett, 2018). Almairi et al. (2021), for example, found that medical students valued the positive role models they associated with the hidden curriculum, particularly their professionalism, responsibility, effective communication, and commitment to excellence.

Although the hidden curriculum’s values were often positive, the tensions between them led to an increased cognitive burden. This was particularly true when students were expected to perform these values (e.g., kindness, learning engagement) in a way aligned with social expectations from majority cultures (e.g., bubbliness, talkativeness). The expectation to act according to these cultural norms was implicitly an expectation to change their typical social habits, based on their own cultures, abilities, and upbringings. The entanglement of the culture-bound performance (e.g., speaking up in class) with the value (e.g., caring about learning) led students from minoritized backgrounds to feel their own ways of enacting these values were poorly understood and de-valued.

The creation and perpetuation of a culture is inevitable and natural (Arrow & Burns, 2003). If most of a program’s faculty and student population come from similar cultural backgrounds, it is unsurprising that the program’s culture would mirror that culture. Those steeped in the programmatic culture may not notice it exists. They may not recognize that it is not value-neutral or the only way to be. Students who enter these programs and do not fit this mold are expected to hold the tensions of the hidden curriculum that others may not even notice. This places an extra burden upon students from minoritized backgrounds who do not share the majority culture.

4.3. Implications for Clinical Identity Development

Graduate programs are a crucial inflection point where students are developing their professional identities (Mak et al., 2022; Plummer & Naidoo, 2023). The lessons of the hidden curriculum shape students’ understanding of what these identities should be (Gupta et al., 2020). Social learning (Bandura, 1977) was a powerful driver in participants’ identity development (Cruess et al., 2019; Holden et al., 2012; Horsburgh & Ippolito, 2018). They learned how they were expected to act in the programs and field through their own social interactions and by watching others. As the hidden curriculum conveys what students are supposed to do, value, and be in their programs, it also teaches them what they are supposed to do, value, and be in their professional lives. These implicit messages convey who and what a “good” clinician is. Graduate programs, therefore, have a responsibility to consider what messages they convey, explicitly or implicitly, about what their fields value. The results of this study indicate that students receive this messaging explicitly through direct communication from the program and peers, implicitly through the way the program and culture are structured, and through the confirmation/disconfirmation of their own pre-existing expectations.

4.4. Limitations

Like all research, qualitative research is subject to the biases and interpretations of its authors. As described in the methods, we have taken care to enhance trustworthiness by considering our positionalities and ensuring participants’ meanings are well described through member checking and data triangulation. Yet, the data analysis process remains subject to individual interpretation.

Additionally, this study is likely only representative of predominantly White programs. Nearly all participants (20/21, 95.2%) described their programs, cohorts, and faculty as predominantly White, including two who attended minority-serving institutions. Therefore, the hidden curriculum described herein is likely tied to these racial demographics. Although these demographics align with the homogeneity of the fields, the hidden curriculum is likely to differ in programs that have a majority of students/faculty from a different cultural background or a more diverse makeup. Future research might look specifically at the hidden curricula in programs where the majority of students or faculty are from minoritized racial backgrounds. Further inquiry into more diverse programs might reveal that such diversity leads to a different hidden curriculum, aspects of which might be protective of students from minoritized groups. These findings could be educational for White-majority programs as well, as they could provide ideas for cultural shifts.

5. Conclusions

If programs are constantly either confirming or refuting students’ expectations for how they are supposed to present themselves in the field and how welcome they are as their true selves, then there is no “neutral” way that a program can be. Instead of assuming their culture is experienced similarly by all students, programs might consider encouraging students to think critically about their programmatic culture and the social expectations of the fields. Programs might consider what values they want to promote in their students and discuss the myriad ways students can demonstrate these values aligned with their culture, neurotype, and dis/ability. This discussion might lead to cultural knowledge-sharing between students and faculty in a way that values students’ expertise.

Faculty might explicitly discuss the hidden curriculum in their program and field, giving students agency to critique it and consider how they do or do not wish to align themselves with these expectations. Interventions that directly discuss the hidden curriculum and its biases have been effective in improving minoritized students’ feelings of belonging and agency (M. C. Jackson et al., 2024; Laiduc & Covarrubias, 2022). Future research should address whether such interventions can increase students’ feelings of agency and belonging within this hidden curriculum. Potential interventions might include reinforcing to minoritized students that their social positionalities may result in unique experiences compared with those of their peers from majority backgrounds. However, these differences are commonplace and not an individual failing. These types of interventions can increase the senses of belonging and empowerment for students from minoritized/marginalized backgrounds. “Wise interventions”, introduced by Walton (2014), do just this and have been shown to increase students’ feelings of belonging and empowerment (Covarrubias et al., 2023; M. C. Jackson et al., 2024; Laiduc & Covarrubias, 2022). Researchers might assess the efficacy of such interventions in PT, OT, and SLP graduate programs and whether they help students maintain their own cultural norms as clinicians. If cultural alignment between client and clinician improves clinical outcomes (Cooper et al., 2003; Shen et al., 2018; Takeshita et al., 2020), then programs must facilitate students’ retention of their own cultural norms as a part of their clinical identity. Otherwise, the fields are losing one of the important benefits of cultivating a representative workforce.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci15070791/s1: Codebook.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.W., M.J.L.-N., C.W.L.; methodology, L.L.W.; formal analysis, L.L.W., M.J.L.-N., C.W.L., K.N.; investigation L.L.W., M.J.L.-N., C.W.L., K.N.; data curation, L.L.W., M.J.L.-N., L.E.N., C.L.R., S.S.P., S.Y.L., K.N., writing—original draft preparation, L.L.W., K.N.; writing—review and editing, M.J.L.-N., C.W.L., L.E.N., C.L.R., S.S.P., S.Y.L.; visualization, L.L.W.; supervision, K.N.; project administration, L.L.W.; funding acquisition, L.L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, grant number 81513.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of [identifying information redacted] (protocol code 2024P000172, approved 19 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The full code book is available as Supplementary Materials. The interview transcripts discussed in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study and are of a sensitive, potentially identifiable nature. Requests to access portions of the datasets should be directed to lwolford@mghihp.edu.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants in this study for their vulnerability in sharing their experiences and ongoing consultation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors each work for or attend a university that houses entry-level PT, OT, and SLP graduate programs. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PT | Physical therapy |

| OT | Occupational therapy |

| SLP | Speech-language pathology |

Appendix A

Unannotated Interview Questions

Adapted from Lempp and Seale (2004), Bandini et al. (2017), and Gupta et al. (2020)

- What does it mean to be a good student in your program?

- What qualities/behaviors/attitudes do you think are most needed to get there?

- What does it mean to be a successful student in your program? You might think of a ‘rising star’ in your department.

- What qualities/behaviors/attitudes are needed to get there?

- How did you learn about these values? How do you know these are the things that are prioritized?

- Let’s imagine that a close friend of yours is about to start the program. You trust them and want the best for them.

- What are the “unwritten rules” that you would let them know about in advance?

- If they wanted to stand out or be a “rising star” in the program, what advice might you give them?

- What is/was your support system or friend group like within the program? What brings you together?

- Professionalism is often discussed and evaluated in programs. Is that something you’ve been evaluated on?

- When you are being evaluated for professionalism in your program, what do you think the faculty and staff are looking for?

- What leads you to believe that? Where did you get that knowledge?

- Do/did you feel a sense of belonging in your graduate program?

- How do you feel that the unwritten rules and expectations we’ve discussed relate to your feelings of belonging in the program? In the field?

- What could your program do to make you feel more like you belonged?

- In what ways have you found yourself changed (either positively or negatively) through your training?

- In summary, what is the take home message for the research team regarding unwritten rules and culture of your program?

Appendix B

Faculty Researcher Positionality Statements

LW: I am a faculty member in an SLP clinical doctorate program. Before that, I was faculty in an SLP master’s program for 6 years. I am also a biracial, second-generation, queer cisgender woman who was raised predominantly by my Taiwanese mother in a very white area. Fitting in was a means of survival. Yet, fitting in with the majority has always clashed with my culture and who I am. My attempts to find the difference between “me” and “performing what is expected of me” have led me to also question the social structures we build and uphold.

MLN: I am an Assistant Professor in a clinical doctorate program for speech-language pathology. Prior to that, I was a clinical faculty member for a master’s SLP program for 6 years. I’m also a bilingual (Spanish-English), bi-cultural, multi-ethnic cisgender woman. I grew up in Puerto Rico and migrated to the US mainland as an adult to attend two different universities for my degrees. My personal experiences with how the hidden curricula of higher education and health professions interact with my values and culture have led me to explore ways to support underrepresented students and challenge the systems within which we operate.

CWL: I am an Adjunct Assistant professor at a graduate school of health professions and Director of Community Excellence, Education and Programs, with a PhD in Social Policy, and a background in sociology and city and regional planning. I have over 10 years of experience in higher education and over 20 years of experience in community engagement and organizational development in community organizations. I am a multi-lingual, cisgender Black American and Cape Verdean American woman.

KN: I am an Associate Professor with 27 years of experience as a physical therapist and 13 years in academia. I am an immigrant, Asian woman who was raised in apartheid South Africa. This experience of extreme segregation and racism influences my decision to operationalize minoritization as referring to both a lack of size and power. My experiences and research have confirmed that strength in numbers does not protect Asian students and faculty from discrimination either in the academy or in the clinical environment.

References

- Ahmed, S. K. (2024). The pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almairi, S. O. A., Sajid, M. R., Azouz, R., Mohamed, R. R., Almairi, M., & Fadul, T. (2021). Students’ and faculty perspectives toward the role and value of the hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: A qualitative study from Saudi Arabia. Medical Science Educator, 31(2), 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armas-Neira, M., Jaimes-Jiménez, I., Turnbull, B., Vargas-Lara, A., López-Covarrubias, A., Negrete-Meléndez, J., Mimiaga-Morales, M., Oca-Mayagoitia, S. M., & Monroy-Ramírez, L. (2024). Under the covert norm: A qualitative study on the role of residency culture on burnout. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrow, H., & Burns, K. L. (2003). Self-organizing culture: How norms emerge in small groups. In The psychological foundations of culture. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Azmand, S., Ebrahimi, S., Iman, M., & Asemani, O. (2018). Learning professionalism through hidden curriculum: Iranian medical students’ perspective. Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine, 11, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Bandini, J., Mitchell, C., Epstein-Peterson, Z. D., Amobi, A., Cahill, J., Peteet, J., Balboni, T., & Balboni, M. J. (2017). Student and faculty reflections of the hidden curriculum: How does the hidden curriculum shape students’ medical training and professionalization? American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 34(1), 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Behmanesh, D., Jalilian, S., Heydarabadi, A. B., Ahmadi, M., & Khajeali, N. (2025). The impact of hidden curriculum factors on professional adaptability. BMC Medical Education, 25(1), 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L. A., Roter, D. L., Johnson, R. L., Ford, D. E., Steinwachs, D. M., & Powe, N. R. (2003). Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139(11), 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias, R., Laiduc, G., Quinteros, K., & Arreaga, J. (2023). Lessons on servingness from mentoring program leaders at a Hispanic serving institution. Journal of Leadership, Equity, and Research, 9(2), 75–91. Available online: http://journals.sfu.ca/cvj/index.php/cvj/index (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Cruess, S. R., Cruess, R. L., & Steinert, Y. (2019). Supporting the development of a professional identity: General principles. Medical Teacher, 41(6), 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B. P., Caston, S., Melvey, D., Maitra, A., Rogozinski, B., & Zajac-Cox, L. (2025). A strategic approach to shift diversity, equity, and inclusion culture in physical therapy education. Advance Online Publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpit, L. (1995). Other people’s children: Cultural conflict in the classroom (1st ed.). New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaufberg, E. H., Batalden, M., Sands, R., & Bell, S. K. (2010). The hidden curriculum: What can we learn from third-year medical student narrative reflections? Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 85(11), 1709–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genoff, M. C., Zaballa, A., Gany, F., Gonzalez, J., Ramirez, J., Jewell, S. T., & Diamond, L. C. (2016). Navigating language barriers: A systematic review of patient navigators’ impact on cancer screening for limited English proficient patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(4), 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiberson, M., & Vigil, D. (2021). Speech-Language Pathology Graduate Admissions: Implications to Diversify the Workforce. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 42(3), 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M., Forlini, C., & Laneuville, L. (2020). The hidden curriculum in ethics and its relationship to professional identity formation: A qualitative study of two Canadian psychiatry residency programs. Canadian Journal of Bioethics, 3(2), 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafferty, F. W., Gaufberg, E. H., & O’Donnell, J. F. (2015). The role of the hidden curriculum in “On doctoring” courses. AMA Journal of Ethics, 17(2), 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R. X. D., Goodman, N. D., & Goldstone, R. L. (2019). The emergence of social norms and conventions. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(2), 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., & Marconi, V. C. (2017). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E., Bowman, K., Stalmeijer, R., & Hart, J. (2014). You’ve got to know the rules to play the game: How medical students negotiate the hidden curriculum of surgical careers. Medical Education, 48(9), 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, B. D., Ginsburg, S., Cruess, R., Cruess, S., Delport, R., Hafferty, F., Ho, M.-J., Holmboe, E., Holtman, M., Ohbu, S., Rees, C., Ten Cate, O., Tsugawa, Y., Van Mook, W., Wass, V., Wilkinson, T., & Wade, W. (2011). Assessment of professionalism: Recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 conference. Medical Teacher, 33(5), 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, M., Buck, E., Clark, M., Szauter, K., & Trumble, J. (2012). Professional identity formation in medical education: The convergence of multiple domains. HEC Forum, 24(4), 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsburgh, J., & Ippolito, K. (2018). A skill to be worked at: Using social learning theory to explore the process of learning from role models in clinical settings. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HRSA Health Workforce. (2024). State of the U.S. health care workforce. National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Available online: https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/state-of-the-health-workforce-report-2024.pdf?preview=true&site_id=837 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Hunter, K., & Cook, C. (2018). Role-modelling and the hidden curriculum: New graduate nurses’ professional socialisation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(15–16), 3157–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, K., & Sasada, S. (2022). Development of a new scale for the measurement of interprofessional collaboration among occupational therapists, physical therapists and speech-language therapists. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy, 35(2), 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, A. A. (2016). (No) Harm in asking: Class, Acquired cultural capital, and academic engagement at an elite university. Sociology of Education, 89(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P. (1968). Life in classrooms. Rinehart and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M. C., Remache, L. J., Ramirez, G., Covarrubias, R., & Son, J. Y. (2024). Wise interventions at minority-serving institutions: Why cultural capital matters. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetty, A., Jabbarpour, Y., Pollack, J., Huerto, R., Woo, S., & Petterson, S. (2022). Patient-physician racial concordance associated with improved healthcare use and lower healthcare expenditures in minority populations. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9(1), 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalili, H., Orchard, C., Laschinger, H. K. S., & Farah, R. (2013). An interprofessional socialization framework for developing an interprofessional identity among health professions students. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(6), 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox-Kazimierczuk, F. A., Tosolt, B., & Lotz, K. V. (2024). Cultivating a sense of belonging in allied health education: An approach based on mindfulness anti-oppression pedagogy. Health Promotion Practice, 25(4), 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiduc, G., & Covarrubias, R. (2022). Making meaning of the hidden curriculum: Translating wise interventions to usher university change. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 8(2), 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiduc, G., Slattery, I., & Covarrubias, R. (2024). Disrupting neoliberal diversity discourse with critical race college transition stories. Journal of Social Issues, 80(1), 308–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempp, H., & Seale, C. (2004). The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: Qualitative study of medical students’ perceptions of teaching. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 329(7469), 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugones, M. (1987). Playfulness, “world”-travelling, and loving perception. Hypatia, 2(2), 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, S., Hunt, M., Boruff, J., Zaccagnini, M., & Thomas, A. (2022). Exploring professional identity in rehabilitation professions: A scoping review. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 27(3), 793–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P. K. (2022). Hegemonic whiteness: Expanding and operationalizing the conceptual framework. Sociology Compass, 16(4), e12973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neve, H., & Collett, T. (2018). Empowering students with the hidden curriculum. The Clinical Teacher, 15(6), 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, L. M., & Burks, K. A. (2022, February 1). Creating a racial and ethnic inclusive environment in occupational therapy education. American Occupational Therapy Association. Available online: https://www.aota.org/publications/sis-quarterly/academic-education-sis/aesis-2-22 (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Plummer, L., & Naidoo, K. (2023). Perceptions of interprofessional identity formation in recent doctor of physical therapy graduates: A phenomenological study. Education Sciences, 13(7), 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S., & Beach, M. C. (2020). Impact of physician race on patient decision-making and ratings of physicians: A randomized experiment using video vignettes. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(4), 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salhi, R. A., Dupati, A., & Burkhardt, J. C. (2022). Interest in serving the underserved: Role of race, gender, and medical specialty plans. Health Equity, 6(1), 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab-Farrell, S. M., Dugan, S., Sayers, C., & Postman, W. (2024). Speech-language pathologist, physical therapist, and occupational therapist experiences of interprofessional collaborations. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 38(2), 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, D., & Wilkinson, T. J. (2022). Widening how we see the impact of culture on learning, practice and identity development in clinical environments. Medical Education, 56(1), 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M. J., Peterson, E. B., Costas-Muñiz, R., Hernandez, M. H., Jewell, S. T., Matsoukas, K., & Bylund, C. L. (2018). The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(1), 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. G., Nsiah-Kumi, P. A., Jones, P. R., & Pamies, R. J. (2009). Pipeline programs in the health professions, part 1: Preserving diversity and reducing health disparities. Journal of the National Medical Association, 101(9), 836–840, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshita, J., Wang, S., Loren, A. W., Mitra, N., Shults, J., Shin, D. B., & Sawinski, D. L. (2020). Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Network Open, 3(11), e2024583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torralba, K. D., Jose, D., & Byrne, J. (2020). Psychological safety, the hidden curriculum, and ambiguity in medicine. Clinical Rheumatology, 39(3), 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traylor, A. H., Subramanian, U., Uratsu, C. S., Mangione, C. M., Selby, J. V., & Schmittdiel, J. A. (2010). Patient race/ethnicity and patient-physician race/ethnicity concordance in the management of cardiovascular disease risk factors for patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care, 33(3), 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Census Bureau. (2024, October 28). Public use microdata sample (PUMS). Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS). Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/microdata.html (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Valencia, R. R. (2010). Dismantling contemporary deficit thinking: Educational thought and practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G. M. (2014). The new science of wise psychological interventions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(1), 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K. L., Degener, S., Tondreau, A., Gardiner, W., Hinman, T. B., Dussling, T. M., Stevens, E. Y., & Wilson, N. S. (2024). Nice girls like us: Confronting white liberalism in teacher education and ourselves. Education Sciences, 14(6), 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyavi, S. T., Hoobehfekr, S., & Tabatabaee, M. (2021). Exploring the hidden curriculum of professionalism and medical ethics in a psychiatry emergency department. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 66, 102885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]