1. Introduction

In educational settings, emotional intelligence is crucial for teacher–student relationships, classroom management, and student well-being. It contributes to creating a positive learning environment, academic success, and socio-emotional skill development (

Fernández Berrocal et al., 2022).

The emotional intelligence of future teachers significantly impacts their attitudes towards inclusion of people with disabilities. Teachers with higher emotional intelligence tend to have more positive attitudes towards inclusion, creating better learning conditions, and adapting their teaching to the needs of students with disabilities (

Voulgaraki et al., 2023). Emotional intelligence also correlates with self-efficacy beliefs, making teachers more confident in including students with disabilities (

Rofiah, 2022). Furthermore, teachers with higher emotional intelligence provide more support to students with disabilities, improving their self-efficacy (

Katsora et al., 2022). Education and teaching influence emotional intelligence levels, with higher education and more experience correlating with higher emotional intelligence (

Varkas, 2022).

Inclusive policies are crucial: they shape diversity strategies and address the intersection of disability and marginalization in education worldwide (

Novo-Corti et al., 2014). Preservice teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion varies; studies report generally positive views, particularly among those with special education experience. Reviews indicate that attitudes can be ambivalent and sensitive to the type of special educational need, underscoring the role of both individual and contextual factors in shaping inclusive intentions and behaviors (

European Journal of Special Needs Education, 2023; see also

Charitaki et al., 2024 for cross-national modeling). Taken together, these findings position teachers as pivotal actors in inclusion policies and identify initial teacher education as a strategic lever for developing skills and dispositions aligned with inclusion.

However, the gender perspective also influences attitudes, with female physical education teachers showing more positive attitudes towards inclusion compared to male teachers (

Rofiah, 2022;

Aldosari, 2022). While gender is a factor, other elements like teaching training and experience also play a significant role. Inclusion training is key in shaping teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion, along with teaching experience and direct experience with students with disabilities (

Alhumaid et al., 2022;

Varkas, 2022).

Sexism and attitudes towards disability are interconnected, with traditional gender role beliefs influencing attitudes towards women with physical disabilities (

Parsons et al., 2017). Sexism in education can affect relationships between teachers and students with disabilities, emphasizing the importance of addressing sexism and providing appropriate training to promote inclusion and equality (

Guidry, 2000). The introduction should briefly place the study in a broad context and highlight why it is important. It should define the purpose of the work and its significance. Teachers play a pivotal role in shaping inclusive school climates, yet the psychological factors that sustain or undermine inclusion are still unevenly understood. Emotional intelligence (EI) has been linked to prosocial orientations and prejudice reduction, whereas ambivalent sexism (hostile and benevolent) may reinforce exclusionary beliefs and practices. In initial teacher education, clarifying how EI relates to sexism and to attitudes toward disability is essential to inform evidence-based training and policy aimed at fostering inclusion.

Inclusive education is understood as the systematic removal of barriers to participation and learning for all learners and the creation of classroom climates that value diversity and equitable opportunities (

UNESCO, 2020). Within this agenda, teachers’ socio-emotional competences—captured in the TMMS facets of emotional attention, clarity, and regulation—are theorized to support instructional responsiveness, classroom management, and the affective conditions for learning (

Salovey et al., 1995;

Fernandez-Berrocal et al., 2004). Evidence across educational settings indicates that EI relates to beneficial outcomes such as academic performance and adaptive classroom functioning, and that emotion regulation skills are associated with teacher well-being and positive emotional climates (

Quílez-Robres et al., 2023;

Wang et al., 2025). Because inclusive environments depend not only on resources but also on teachers’ beliefs, initial teacher education is a strategic lever for fostering dispositions aligned with inclusion and for preventing discriminatory attitudes. In particular, addressing prejudicial gender beliefs conceptualized by the ambivalent sexism framework—hostile and benevolent components—may reduce barriers to equitable participation and complement the development of EI competences (

Glick & Fiske, 1996). Against this background, the present study examines how EI and ambivalent sexism jointly relate to attitudes toward disability in prospective teachers, providing evidence relevant to the design of initial teacher education curricula that promote inclusive school environments.

Against this background, we next define the core constructs examined in this study—emotional intelligence (EI), ambivalent sexism, and attitudes toward disability—and outline the integrative rationale guiding our analyses.

Definitions of key constructs

Emotional intelligence (EI) can be conceptualized either as an ability “to perceive, use, understand, and manage emotions” or as a trait, i.e., a constellation of self-perceptions about one’s emotional functioning (

Mayer et al., 2016;

Petrides et al., 2016). Ambivalent sexism comprises two correlated yet distinct components: hostile sexism (HS) and benevolent sexism (BS) (

Glick & Fiske, 1996). Attitudes toward disability are multidimensional evaluations shaped by knowledge, contact, and contextual factors in educational settings (

Wang et al., 2025). Taken together, these definitions motivate the following integrative model.

Integrative theoretical model and rationale

Building on frameworks linking emotion regulation skills with reduced generalized prejudice, we propose an integrative account in which higher EI is associated with lower ambivalent sexism (HS and BS) and, consequently, with more inclusive attitudes toward disability. Accordingly, we test a mediation model in which ambivalent sexism partially explains the EI–attitudes association after adjusting for age, sex, prior contact with disability, inclusive education training, and institution.

Objectives

General

To evaluate the emotional intelligence of future teachers and its relationship with the attitude towards people with disabilities, sexism, and bullying behaviors.

Specific

Identify the levels of emotional intelligence in its components of attention, clarity, and emotional regulation in future teachers.

Identify the attitude of future teachers towards people with disabilities according to sex.

Establish the type and degree of sexism (hostile and benevolent) most present in future teachers.

Determine the prevalence, type, and degree of bullying, both from the perspective of victims and aggressors in future teachers.

Determine the relationship between the perception of attention, clarity, and emotional regulation and the perception of bullying behavior from the point of view of the aggressor in future teachers.

To determine the relationship between the perception of attention, clarity, and emotional regulation and the perception of bullying behavior from the point of view of the victim in future teachers.

Determine the relationship between the perception of attention, clarity, and emotional regulation and the attitude towards people with disabilities in future teachers.

Determine the relationship between the perception of attention, clarity, and emotional regulation and the degree of sexism in future teachers.

2. Materials and Methods

This research was oriented towards a non-experimental design under a quantitative approach, utilizing data collection to evaluate hypotheses based on numerical measurement and statistical analysis to prove behavioral patterns and test theories.

Population and type of sampling

The participating population was selected by convenience sampling and is made up of 1004 future teacher educators from Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (Faculty of Education and Sports Sciences and Interdisciplinary Studies, Fuenlabrada Campus), the University of Zaragoza (Faculty of Social and Human Sciences of Teruel) and the National University of Distance Education (UNED) who were administered questionnaires. The self-declared gender of the participating student teachers is distributed as follows: 92.5% are female and 7.5% are male.

Instruments

Perceived emotional intelligence has been evaluated through the TMMS-24, which consists of a synthesis and adaptation to Spanish of the American Trait-Meta Mood Scale test -TMMS-48 (

Salovey et al., 1995), carried out by

Fernandez-Berrocal et al. (

2004) and in which they maintain the items that have a more significant intrinsic consistency. The TMMS-24 is a self-report measure that evaluates meta-knowledge about one’s own emotional state using a 24-item trait scale (8 items per factor) with a Likert-type scale from 1 to 5 that starts from the opinion ‘not at all’, ‘agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’, and 3 subscales according to the three fundamental components of intrapersonal emotional intelligence based on the mental ability model of John Mayer and Peter Salovey (1997). Cronbach’s alpha for the overall instrument was 0.94.

CAME: School Bullying Questionnaire (2003)

The assessment of bullying between peers will be conducted through the CAME questionnaire which adopts as a model the questionnaire “Instrument to assess the incident of involvement in bully/victim”, “presented by Rigby and Bagshaw (2003). The adaptation of said questionnaire has been formulated and authorized by the work team made up of Santiago Yubero, Elisa Larrañaga, and Raúl Navarro to extract data about the level of participation of both boys and girls in the phenomenon of abuse between individuals from the position of the aggressor and the victim.

This instrument was previously used in different studies investigating the phenomenon of peer abuse among Spanish adolescents (

Navarro et al., 2011;

Yubero et al., 2017). Consequently, CAME is configured around two sections. The first of them brings together the data relevant to the figure of Victim and the second refers to that of Aggressor in relation to the various modalities of abuse between equals in the educational field, particularly, physical aggression (hitting or pushing a classmate); verbal (gossiping about an equal without their presence or slandering about the, both direct and indirect); and social exclusion with respect to the peer group (rejecting, dispensing with, or not allowing participation in activities).

The questionnaire is made up of 5 items with a Likert model response type of 4 questions ranging from 0 = Never to 3 = Daily. In addition, two more questions have been added to the CAME on whether they have ever felt harassed and if they ever believe they have harassed someone.

General Scale of Attitudes towards People with Disabilities (2016)

The General Scale of Attitudes towards People with Disabilities (

V. B. Arias et al., 2016) emerged to update and validate previous versions of the scale (

B. Arias, 1993;

B. Arias et al., 1995;

Verdugo et al., 1994;

Verdugo et al., 1995). This has made it possible to have a psychometrically sound instrument to evaluate attitudes towards people with disabilities, and for application among education professionals. It consists of a scale of 31 summative estimates with four degrees of agreement: strongly agree (MA); quite agree (BA); strongly disagree (BD); strongly disagree (MD). In this way, the response of the person evaluated shows the intensity of their agreement or disagreement with each item related to the attitude referent. In all cases, a higher score denotes more favorable attitudes. Cronbach’s alpha for the general instrument was 0.92.

Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI)

The ASI (

Glick & Fiske, 1996) comprises 22 Likert-type items scored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) and yields a total score plus two 11-item subscales: hostile sexism (HS) and benevolent sexism (BS). Higher scores indicate higher levels of sexist beliefs. We used the Spanish adaptation by

Expósito et al. (

1998); evidence from Latin American validations was considered when aligning item wording. In the present sample, internal consistency was α = 0.89 (ASI total), α = 0.87 (HS), and α = 0.83 (BS).

Scoring and categorization.

For inferential analyses, ASI total, HS, and BS were treated as continuous variables to avoid information loss due to artificial categorization. Where descriptive profiles are presented, low/medium/high groups were created using sample terciles; these cut points are data-driven, have no clinical meaning, and are used exclusively for descriptive purposes.

Informed consent

The instruments were converted to digital format through the Google forms platform. Before beginning their answers, the students had to read the objectives of the study and approve their informed consent. With the internal registration number: 2903202314223 the Research Ethics Committee of the Rey Juan Carlos University approved this research. The information was treated with strict confidentiality.

Analysis of data

The analysis was conducted with the IBM SPSS Statistics program (IBM, v.26.0). The level of statistical significance was established at p ≤ 0.05. Normality was checked through the Kolmogorov–Smirnov analysis (p ≥ 0.05) and, consequently, parametric analyzes were used. All variables are presented as mean ± SD (standard deviation). Student’s t test was used to analyze differences based on gender and Pearson Correlation to determine the relationship between the study variables.

To examine whether emotional intelligence (EI) predicts Attitudes toward Disability—Total beyond covariates, and whether ambivalent sexism adds explanatory power, we conducted hierarchical multiple regressions with Attitudes toward Disability—Total as the dependent variable. Step 1 (covariates) included age, sex (0 = female, 1 = male), prior contact with disability (0/1), inclusive education training (0/1), and university (dummy-coded). Step 2 added EI (EI–Total). Step 3 added ambivalent sexism—hostile sexism (HS) and Benevolent Sexism (BS). We checked standard assumptions (linearity, normality of residuals, homoscedasticity) and assessed multicollinearity using variance inflation factors (VIF). We report unstandardized coefficients (b, SE), standardized coefficients (β), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), exact p-values, R2, ΔR2, and ΔF (two-tailed tests, α = 0.05). We use dots as decimal separators; means/SDs are reported with two decimals and p-values with three.

3. Results

To facilitate the reading of this section, the results presented are grouped according to the specific objectives set for this research.

Identify the levels of emotional intelligence in its components of attention, clarity, and emotional regulation in future teachers.

As seen in

Table 1 below, women scored higher than men on Attention (M = 31.63, SD = 7.01 vs. M = 29.39, SD = 5.86), a statistically significant difference (

p = 0.007) with a small effect size (Cohen’s

d ≈ 0.32). Differences were not significant for Clarity (M = 23.72, SD = 6.17 vs. M = 22.97, SD = 3.13;

p = 0.299;

d ≈ 0.13) or Regulation (M = 26.23, SD = 6.55 vs. M = 26.48, SD = 6.29;

p = 0.753;

d ≈ 0.04). Overall, only Attention shows a sex-related difference, and its magnitude is small.

Identify the attitude of future teachers towards people with disabilities according to sex.

As seen in

Table 2 below, the results are presented to indicate attitudes towards people with disabilities in both sexes: 88.9% show neutral attitudes, indicating a lack of extreme opinions. Although the majority have neutral attitudes, the small percentage with negative attitudes (11.1%) stands out as an area of attention for possible educational interventions or awareness programs. The results indicating the attitudes towards people with disabilities for the male sex are as follows. A total of 24.0% of male respondents show negative attitudes towards disability, which could manifest in prejudice, stigmatization, or other negative responses towards people with disabilities. On the other hand, 76.0% of male respondents have a neutral attitude, which suggests that the majority of them do not show extreme opinions, either positive or negative, regarding disability. Likewise, the results are presented to indicate the attitudes towards people with disabilities for the female sex. A total of 10.0% of the female respondents have negative attitudes towards disability and 90.0% of the female respondents have a neutral attitude towards disability.

Establish the type and degree of sexism (hostile and benevolent) most present in future teachers.

Table 3 shows that 61.3% of the male participants present a high level of hostile sexism, 25.3% show medium levels of hostile sexism, and 13.3% present low levels of hostile sexism. On the other hand, 56.1% of women present low levels of hostile sexism, 28.6% show medium levels of hostile sexism, and 15% show high levels of hostile sexism. Results also show that 81.6% of women present low levels of benevolent sexism, whereas 49.3% of men present medium levels of benevolent sexism. Finally, 78.4% of the total group (which includes both sexes) presents low levels of benevolent sexism. This means that most people in this group, regardless of their gender, have attitudes that are considered less sexist or stereotypical.

Determine the prevalence, type, and degree of bullying, both from the perspective of victims and aggressors in future teachers.

Types of aggressive tendencies from the perspective of the aggressor

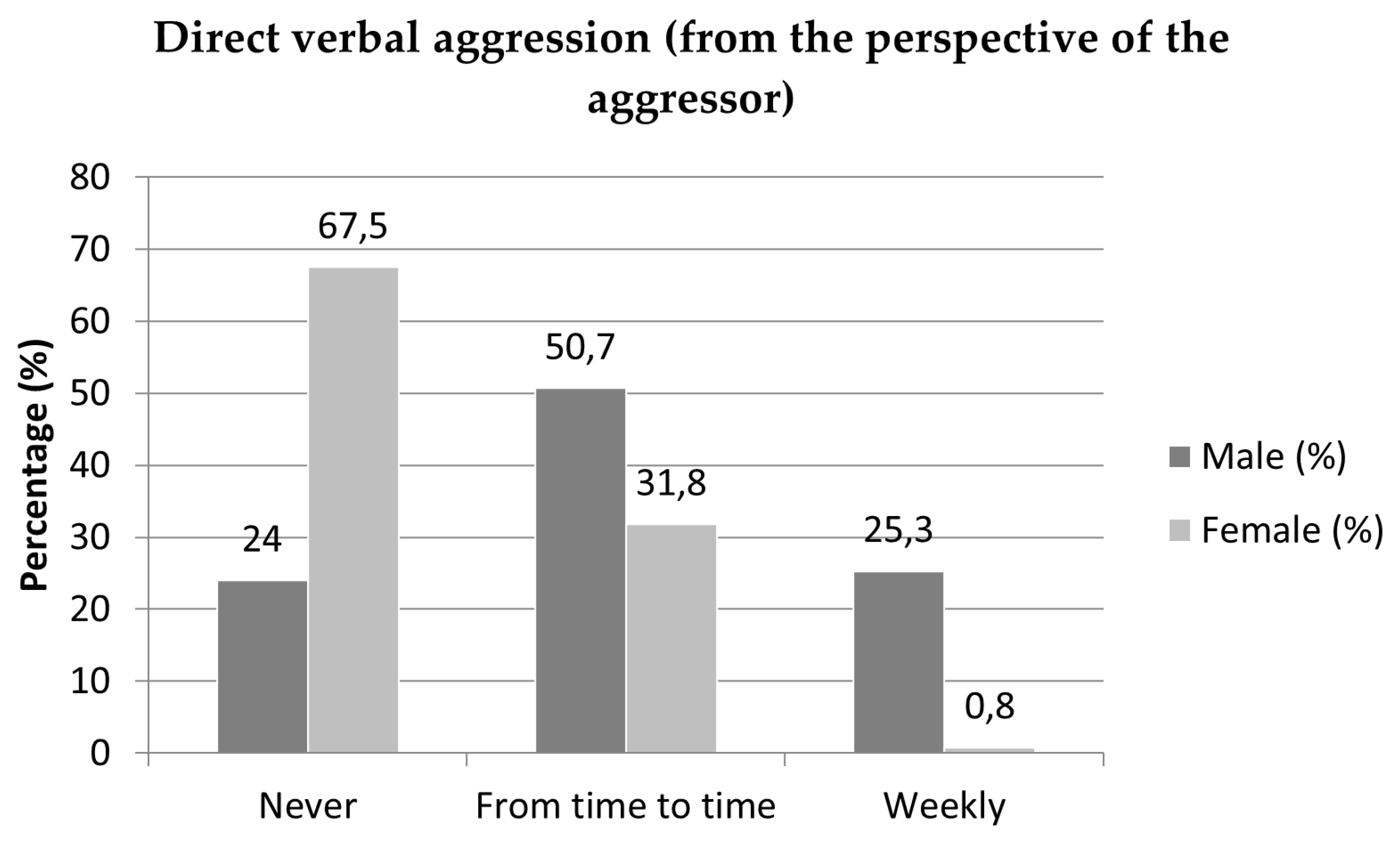

The results obtained allow us to identify differentiated patterns according to the type of verbal aggression exercised by future teachers, considering the gender variable as the axis of comparative analysis. As shown in

Figure 1, direct verbal aggression shows a higher prevalence among men: 50.7% say they have exercised it occasionally (“occasionally”) and 25.3% weekly. On the other hand, 67.5% of women declare that they have never exercised it, and only 0.8% admit to a weekly occurrence.

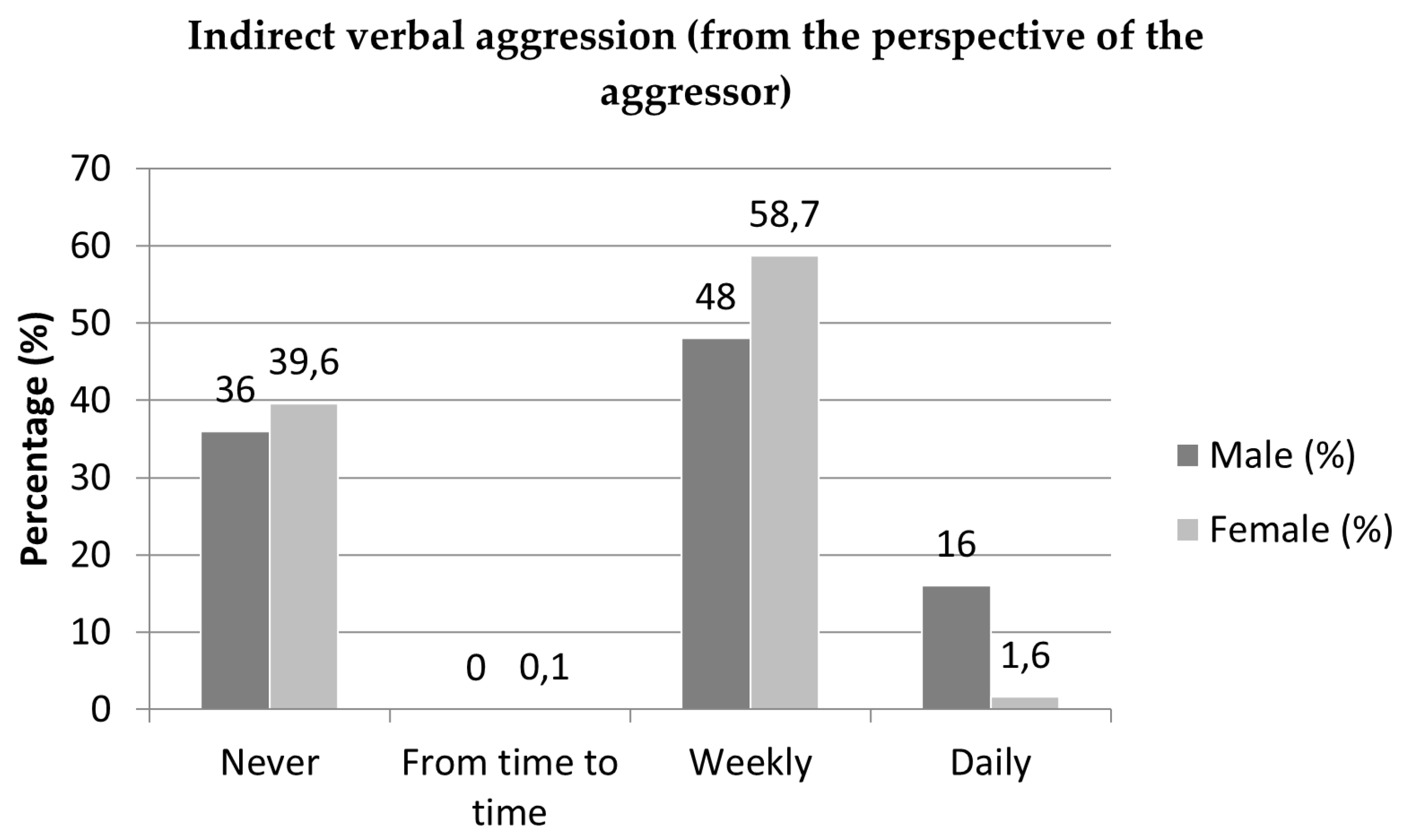

On the other hand, as can be seen in

Figure 2, indirect verbal aggression—associated with behaviors such as rumor, verbal exclusion, or covert defamation—shows a different distribution. In this case, 58.7% of women say they exercise it weekly, and 1.6% daily. Men also acknowledge their significant involvement in this type of aggression, with 48% reporting weekly and 16% daily. However, it is striking that no man has opted for the “occasionally” category, which could reflect a response bias or a pattern of polarized perception around this type of behavior.

Table 4 presents the distribution of frequencies of physical aggression—in its direct and indirect modalities—according to the sex of the self-declared aggressor. In the case of direct physical aggression, there is a majority tendency towards non-participation: 96.0% of men and 91.3% of women say they have never engaged in this behavior. However, 8.7% of women and 4.0% of men admit to having exercised it “from time to time”, which suggests the persistence of this type of aggression in educational environments, although at low levels. Indirect physical aggression—such as covert forms of physical harm or manipulation by third parties—presents a more worrying distribution. Among men, 25.3% admit to having participated occasionally and 0.0% weekly, while 74.7% declare that they have never done so. In women, 11.4% admit to occasional participation and 0.8% weekly, with 87.8% denying having done so.

Table 5 shows the frequency in which prospective teachers acknowledged engaging in exclusion-based aggression, disaggregated by sex. This form of relational aggression consists of ostracizing a person from the group or restricting access to social spaces as a means of harassment. Among men, 62.7% reported never engaging in this behavior, 24.0% acknowledged doing so sometimes, and 13.3% reported daily engagement. In contrast, among women, 86.8% denied ever engaging in it, 12.5% reported doing so sometimes, and 0.8% weekly; no woman reported daily engagement. These data indicate that although most respondents deny engaging in this type of aggression, men are overrepresented at the higher-frequency levels, particularly daily.

Levels of aggressive tendencies from the perspective of the aggressor

The results for this item indicate that 56.3% of the women in the study present medium levels of aggressive tendencies, while 38.7% of men show medium levels of aggressive tendencies. Compared to the female group, there seems to be a lower proportion of men with this tendency. Considering both sexes, 55% of all participants present medium levels of aggressive tendencies.

The results indicate a low incidence of direct physical aggression among the surveyed students but a more significant involvement in indirect physical aggression. Gender differences are noted in direct verbal aggression, with a higher proportion of men admitting their participation compared to women. Additionally, more than 50% of participants admit to weekly participation in indirect verbal harassment. Differences between men and women are also identified in harassment through exclusion, with greater occasional participation by men. Finally, more than 50% of the participants exhibit medium levels of aggressive tendencies from the perspective of the aggressor.

Types of aggressive tendencies from the victim’s perspective

As shown in

Table 6, 63.4% of the women stated that they have never been directly verbally harassed, while 48.0% of men agreed with the female group in never having been directly verbally harassed. However, 31.7% of women reported having been victims of direct verbal harassment from time to time, while 38.7% of men also reported having been victims of direct verbal harassment from time to time. This proportion is similar to that of women, indicating that a considerable percentage of men have also experienced this type of harassment.

The results presented in that table suggest that indirect verbal harassment is an experience that has been reported by a considerable proportion of participants, especially in the male group where around 50.7% indicated having experienced it from time to time. Perception varies between men and women, with a slightly higher percentage of women (48.2%) indicating that they have never experienced indirect verbal harassment. A total of 47.3% of all participants (both sexes) responded that they have never been a victim of indirect verbal harassment.

Regarding direct physical aggression, clear differences were identified according to sex, as shown in

Table 7. A total of 61.3% of men reported not having been a victim of this type of aggression, while 38.7% indicated that they had experienced it from time to time. In contrast, 85.3% of women said they had not been physically assaulted directly, compared to 14.7% who reported having been physically assaulted occasionally.

In relation to indirect physical aggression, the differences by sex were more marked. Only 36.0% of men said they had not suffered from it, while 38.7% indicated that they had experienced it from time to time, 12.0% weekly and 13.3% daily. In the case of women, 83.7% reported not having been a victim of indirect physical aggression, 15.5% reported having experienced it occasionally, 0.8% weekly, and none daily.

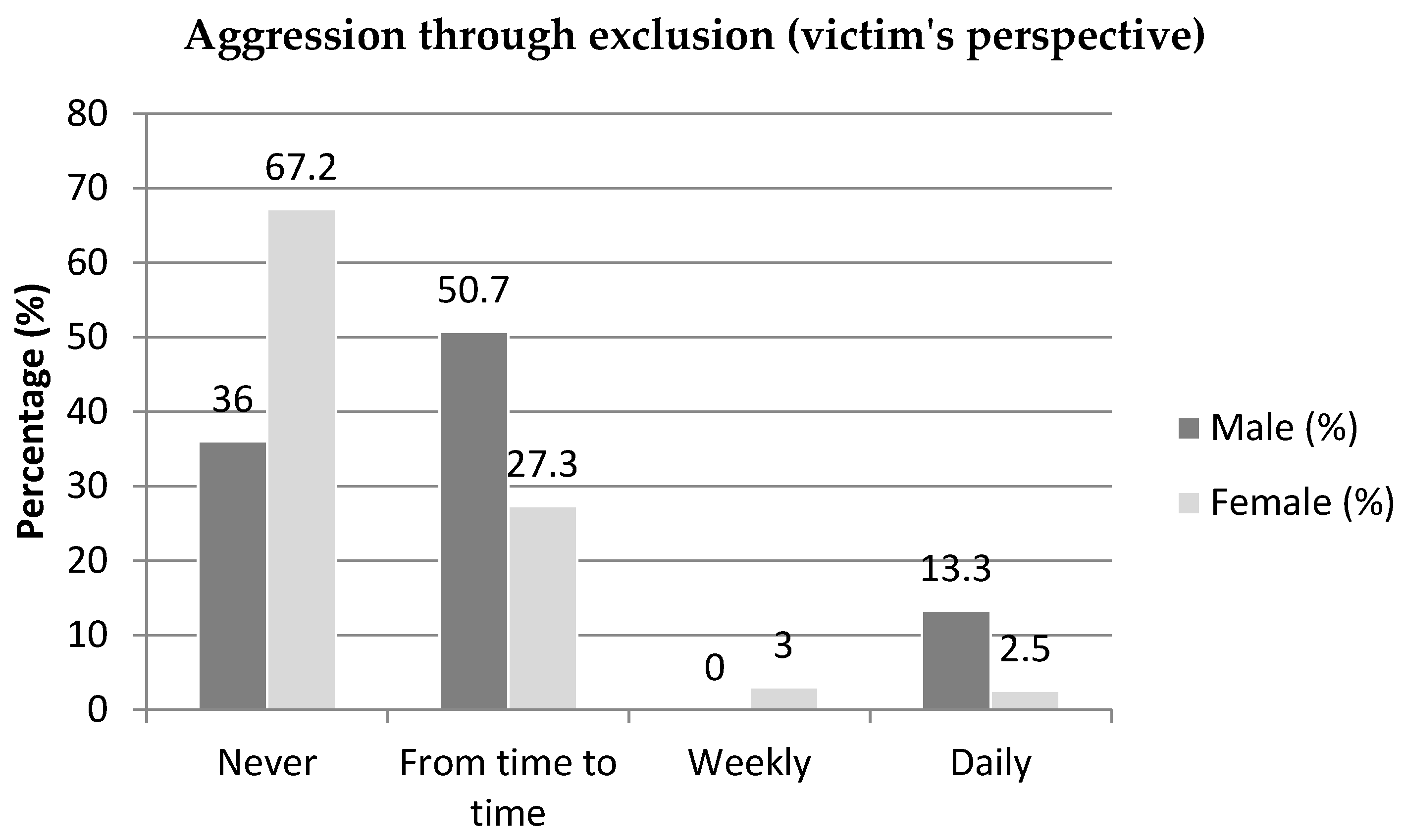

The results presented in

Figure 3 indicate that harassment through exclusion is an experience that has been reported by a considerable proportion of participants, especially in the male group where around 50.7% indicated having experienced it from time to time. However, a significant majority of women (67.2%) have never.

Levels of aggressive tendencies from the victim’s perspective.

The results about Levels of aggressive tendencies from the victim’s perspective indicate that 57.3% of the female group reported low levels of aggressive tendencies from the victim’s perspective while 29.5% of this group reported medium levels of aggressive tendencies from the victim’s perspective. Likewise, 48.0% of the male group reported low levels of aggressive tendencies from the victim’s perspective and of this group, 25.3% presented high levels of aggressive tendencies from the victim’s perspective.

Overall, the majority of participants, regardless of gender, report not having experienced direct physical aggression. However, it is observed that a significant percentage of men have experienced indirect physical harassment. In relation to direct verbal aggression, the majority of women and a considerable proportion of men have not been victims, but a significant percentage of both genders have occasionally experienced direct verbal harassment. Regarding indirect verbal harassment, about half of men report having experienced it occasionally, while a slightly higher percentage of women report not having experienced it. Regarding harassment through exclusion, men stand out as they reported having experienced it occasionally, whereas the majority of women in the sample indicate that they have not suffered this type of harassment. In terms of levels of aggression perceived by the victim, the majority of women report low levels of aggression, while a significant percentage of men have experienced high levels of aggression.

In summary, the discrepancy in perceived levels of aggression from the victim’s perspective, with a majority of women reporting low levels and a significant percentage of men experiencing high levels, highlights the importance of considering these perceptions when designing specific interventions. The results also highlight the complexity of aggression dynamics in the student context, highlighting the need for differentiated approaches and specific strategies to address different types of aggression and gender variations. It would be important to develop a training module to empower students and help institutions produce a mechanism to deal with harassment cases.

Determine the relationship between the perception of attention, clarity and emotional regulation and the perception of bullying behavior from the point of view of the aggressor in future teachers.

The results in

Table 8 indicate a correlation that is significant at the 0.03 level (two-tailed). This indicates that the observed correlation is unlikely to be the result of chance alone. The correlation is −0.094, showing a weak negative relationship between the “harassment” variables from the perspective of the aggressor and the “clarity” variable. A negative correlation suggests that as one variable increases, the other tends to decrease, and vice versa. However, a correlation of −0.094 is considered weak, meaning that the relationship between these two variables is not very strong. There is no correlation between the variables Attention and Regulation.

Correlation between Emotional Intelligence and Bullying

Below in

Table 8, The three EI dimensions were positively intercorrelated (Attention–Clarity: r = 0.59 *; Attention–Regulation: r = 0.41 *; Clarity–Regulation: r = 0.45 *). EI was positively related to attitudes toward disability, with coefficients ranging from 0.14 * (Clarity) to 0.29 * (Attention) and negatively related to ambivalent sexism—small effects for BS (r = −0.07 * to −0.10 *) and HS (r = −0.10 to −0.12 *). BS and HS showed a moderate positive intercorrelation (r = 0.52 *). Regarding bullying, aggressor involvement correlated negatively with EI–Clarity (r = −0.09 *) and positively with BS (r = 0.12 *) and HS (r = 0.26 *), whereas victim involvement correlated positively with EI–Attention (r = 0.19 *), attitudes toward disability (r = 0.10 *) and with both BS (r = 0.08 *) and HS (r = 0.20 *). Other associations were small and non-significant (e.g., aggressor with EI–Attention/Regulation: r ≈ 0.01; Regulation with BS/HS: r = −0.03 to −0.06). Overall, the pattern supports that higher EI aligns with more favorable attitudes toward disability and lower ambivalent sexism, while sexist beliefs are associated with greater bullying involvement, especially from the aggressor perspective.

Hierarchical regressions (

Table 9). EI dimensions in Step 1 explained 9% of the variance in attitudes toward disability (R

2 = 0.09, F = 33.84,

p < 0.001). Adding ambivalent sexism in Step 2 significantly improved model fit (ΔR

2 = 0.03, ΔF(2, 998) = 16.79,

p < 0.001), yielding a final R

2 = 0.12. In the final model, Attention (β = 0.29, 95% CI [0.22, 0.36],

p < 0.001) and Regulation (β = 0.09, [0.03, 0.16],

p = 0.007) were positive predictors, whereas Clarity showed a small negative association (β = −0.09, [−0.17, −0.01],

p = 0.019). Hostile sexism emerged as a negative predictor (β = −0.20, [−0.26, −0.13],

p < 0.001), while benevolent sexism was not significant (β = 0.06, [−0.01, 0.12],

p = 0.111).

4. Discussion

The hierarchical regressions provided the clearest test of our framework. EI subdimensions (Attention, Clarity, Regulation) explained 9% of the variance in attitudes toward disability, and adding ambivalent sexism increased explained variance to 12% (ΔR

2 = 0.03). In the final model, Attention (β = 0.29) and Regulation (β = 0.10) were positive predictors of more favorable attitudes, whereas hostile sexism was a negative predictor (β = −0.19); benevolent sexism did not add unique variance once hostile sexism and EI were included. The small negative coefficient for Clarity (β = −0.10) most plausibly reflects suppression given the moderate intercorrelations among EI subdimensions (r = 0.41–0.59), rather than a substantive inverse relation with inclusive attitudes (

Salovey et al., 1995;

Fernandez-Berrocal et al., 2004).

These model-based results align with the zero-order associations. EI correlated positively with attitudes toward disability (r = 0.14–0.29) and negatively—albeit modestly—with both benevolent and hostile sexism. Hostile and benevolent sexism were moderately intercorrelated (r = 0.52), consistent with the ambivalent sexism framework that distinguishes yet links the two components (

Glick & Fiske, 1996;

Expósito et al., 1998). Bullying involvement displayed a coherent pattern: aggressor involvement correlated positively with hostile sexism (r = 0.26) and negatively with EI–Clarity (r = −0.09), whereas victim involvement correlated positively with EI–Attention (r = 0.19) and, weakly, with more favorable disability attitudes (r = 0.10).

Taken together, the evidence supports the conceptual view outlined in the Introduction: emotion-related skills—especially noticing and regulating emotions—align with more inclusive evaluations, whereas ambivalent sexist beliefs—particularly the hostile component—undermine such attitudes (

Salovey et al., 1995;

Fernandez-Berrocal et al., 2004;

Glick & Fiske, 1996;

Expósito et al., 1998). Descriptive profiles by sex (men more often in high-sexism categories; women in low categories) help contextualize the unique negative association of hostile sexism with attitudes, beyond EI and covariates.

Implications for teacher education follow directly: programs that cultivate emotional attention and regulation (TMMS-aligned competences) and explicitly **challenge ambivalent sexism—especially hostile sexism—**may foster more favorable attitudes toward disability (

B. Arias, 1993;

B. Arias et al., 1995;

Verdugo et al., 1994,

1995;

V. B. Arias et al., 2016). Given that benevolent sexism did not predict attitudes once hostile sexism and EI were considered jointly, prevention and training may prioritize hostile content while still addressing the broader ambivalent framework to avoid “soft” legitimations of inequality.

Several limitations warrant caution. The design is cross-sectional, precluding causal inference. All measures are self-reports, which raises the possibility of common-method variance and social desirability. The sex distribution was highly unbalanced (women >> men), constraining precision in subgroup contrasts. Finally, the tercile-based categorization of sexism was used only for descriptive profiling; all inferential tests relied on continuous ASI scores (

Glick & Fiske, 1996;

Expósito et al., 1998).

Objective-wise summary

Objective 1 (EI levels): Women scored higher on Attention; Clarity and Regulation showed negligible sex differences.

Objective 2 (Attitudes by sex): Overall sex differences were modest and interpreted cautiously given the unbalanced group sizes.

Objective 3 (ASI profiles): HS and BS were moderately intercorrelated; men were overrepresented in high-sexism categories, women in low-sexism categories.

Objective 4 (Bullying prevalence): Most participants denied involvement; men were relatively overrepresented among higher-frequency aggressor categories.

Objective 5 (EI and bullying—aggressor): Aggressor involvement correlated negatively with EI–Clarity (r = −0.09); associations with Attention and Regulation were trivial.

Objective 6 (EI and bullying—victim): Victim involvement correlated positively with EI–Attention (r = 0.19) and weakly with attitudes (r = 0.10).

Objective 7 (EI and attitudes): EI correlated positively with attitudes (r ≈ 0.14–0.29); in regressions, Attention (β = 0.29) and Regulation (β = 0.10) were unique positive predictors.

Objective 8 (EI and ASI): EI correlated negatively with HS/BS (small effects); HS uniquely predicted lower attitudes (β = −0.19) after controlling for EI and covariates.