Supporting Self-Regulated Learning in Primary Education: Using Written Learning Guides in the Lessons

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Supporting Self-Regulated Learning in the Classroom

- Cognitive (e.g., activating prior knowledge, summarising key information, making connections, self-assessment, organising materials and knowledge, problem solving);

- Metacognitive (e.g., planning, including goal setting, monitoring, including tracking progress and adjusting learning activities as needed, reflecting, i.e., analysing one’s learning process and evaluating strategies);

- Behavioural (resource management, e.g., utilising collaboration skills, seeking help from peers and teachers, organising the learning environment, selecting learning materials, feedback, e.g., obtaining and analysing information about one’s learning);

- Motivational strategies (self-motivation, e.g., belief in one’s abilities, enhancing self-efficacy, and fostering a positive attitude; and action control, e.g., avoiding distractions, focusing techniques, and steering clear of negative thoughts).

1.2. Learning Guide

- What are the key structural components of teacher-created learning guides, and how do these components create opportunities to support primary school students’ self-regulated learning?

- In what ways do high-SRL classroom characteristics manifest in lessons where learning guides are in use?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Individual Interviews with Teachers

2.2.2. Classroom Observation

2.2.3. Analysis of Written Learning Guides

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

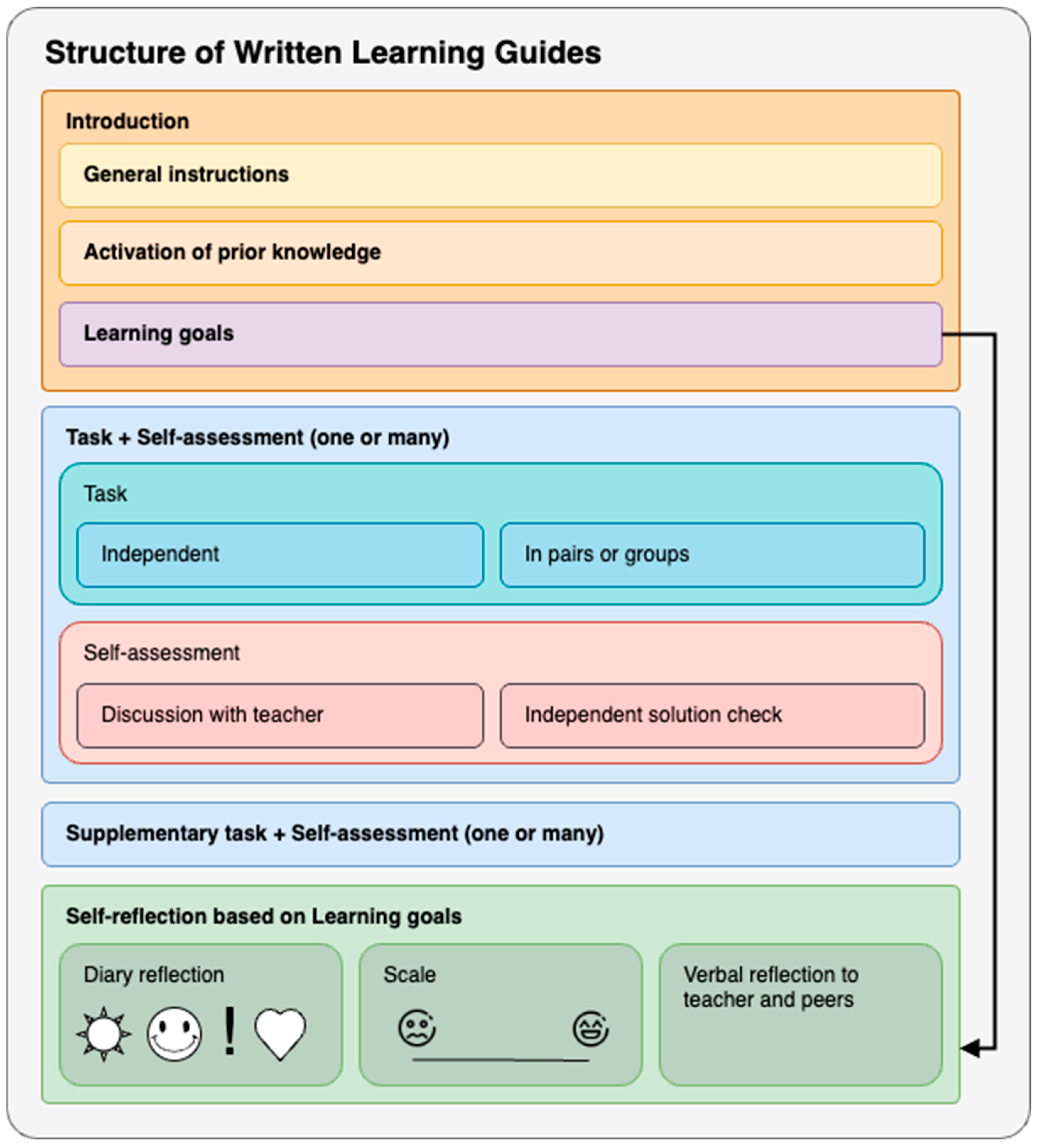

3.1. Structure of the Learning Guides

- Introduction: general instructions, activation of prior knowledge, and goal setting;

- Tasks: activities accompanied by opportunities for self-assessment;

- Self-Analysis: reflection on the learning process.

3.2. The Reflection of High-SRL Classroom Characteristics in Learning Guides and Their Use in the Lessons

3.2.1. Choice Option

3.2.2. Challenge Control

3.2.3. Self- and Peer Assessment

3.2.4. Instrumental Support from Teacher and Peers

3.2.5. Evaluation Practises

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Teacher | Class/Study Group | Number of Learning Guides Used | Time Allocated to Students for Working According to the Learning Guide | Subjects Covered in the Learning Guide | Which Learning Guide Was Used | Number of Tasks/Number of Learning Guides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Grade 2 (20 students) | 4 | 9 × 45 = 405 min | Estonian language Literature Mathematics Natural science | 2 subject-specific 2 whole-school day | 4 learning guides: 2 subject-specific (20–22 work steps) 2 whole-school day guides (longer one with 53 work steps) |

| B | Grade 2 (21 students) | 1 | 120 + 45 = 165 min | Estonian language Literature Mathematics Natural science | 1 whole-school day guide | 1 learning guide with 6 “nests”, totalling 36 work steps |

| C | Grade 1 (17 students) | 6 | 80 + 45 = 125 min | Estonian language Mathematics Natural science | 1 whole-school day guide | 6 “centres” learning guides, each with 2–4 work steps. A total of 20 work steps |

| Teacher A | Teacher B | Teacher C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure of the learning guide | General instructions, learning objectives, 4 tasks + self-assessment, self-analysis | General instructions, learning objectives, 6 “nest” tasks + self-assessment, self-analysis | Recalling prior knowledge, task completion + self-assessment, self-analysis |

| Structure of the tasks | 4 thematic tasks, varying lengths and detailed instructions, covering different subjects and activities, incorporation of integration | 6 thematic “nest” tasks, with detailed instructions, covering different subjects and activities, utilisation of integration | 6 “centres”, up to 4 instructions per centre, covering different subjects and activities, incorporation of integration |

| Use of learning materials | Textbooks, workbooks, iPads, QR codes, experimental tools | Textbooks, workbooks, iPads, QR codes, craft materials | Textbooks, workbooks, iPads, QR codes, craft materials |

| Self-assessment | Control sheets, discussions with the teacher | Control sheets, discussions with the teacher | Control sheets, discussions with the teacher |

| Self-evaluation | Self-evaluation in a diary, use of symbols, reflection on completed work with the teacher | Self-evaluation in a diary, description of strengths and areas for improvement, reflection on completed work with the teacher | Self-analysis by drawing faces with different emotions, reflection on completed work with the teacher |

| Freedom of choice | The learner was able to choose the order, time, and place for completing tasks | The learner was able to choose a partner from the assigned group and an additional task | The learner was able to choose the order and time for completing tasks, three out of six centres were optional |

| Classroom environment | Flexible seating options, opportunity to choose work location | The “nests” have designated workstations, structured rotation took place | The “centres” have designated workstations in the classroom, students complete a record of finished “centres” |

| Teacher’s role | Assigned learning partners, monitored classroom activities, intervened minimally, assisted with technical issues when needed, supported students in need with guiding questions, orally assessed students’ achievement of learning outcomes | Formed groups, determined the order of “nest” rotations, set the time for completing each “nest”, directed movement between “nests”, monitored classroom activities, assisted with technical issues when needed, supported students in need with guiding questions, orally assessed students’ achievement of learning outcomes | Assigned three mandatory centres, monitored students’ independent work, intervened minimally, assisted with technical issues when needed, supported students in need with guiding questions, orally assessed students’ achievement of learning outcomes |

References

- Azevedo, R., Bouchet, F., Duffy, M., Harley, J., Taub, M., Trevors, G., Cloude, E., Dever, D., Wiedbusch, M., Wortha, F., & Cerezo, R. (2022). Lessons learned and future directions of metatutor: Leveraging multichannel data to scaffold self-regulated learning with an intelligent tutoring system. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 813632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barner-Barry, C. (1986). An introduction to nonparticipant observational research techniques. Politics and the Life Sciences, 5(1), 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastani, H., Bastani, O., Sungu, A., Ge, H., Kabakcı, O., & Mariman, R. (2024). Generative AI can harm learning. Available at SSRN, 4895486. Available online: https://hamsabastani.github.io/education_llm.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Biesta, G., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and Teaching, 21(6), 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C., & Raver, R. (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: A developmental psychobiological approach. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 711–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishi, A., Khosravi, H., Sadiq, S., Gašević, D., & Siemens, G. (2024). Impact of AI assistance on student agency. Computers & Education, 210, 104967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dignath, C., & Veenman, M. V. (2021). The role of direct strategy instruction and indirect activation of self-regulated learning—Evidence from classroom Dignath observation studies. Educational Psychology Review, 33(2), 489–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A. L., Quinn, P. D., & Tsukayama., E. (2012). What no child left behind leaves behind: The roles of IQ and self-control in predicting standardized achievement test scores and report card grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, A. L., Tsukayama, E., & May, H. (2010). Establishing causality using longitudinal hierarchical linear modeling: An illustration predicting achievement from self-control. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1(4), 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabregat Fillet, J., Lleixà Arribas, T., Martinez, F., & Tierno, J. M. (2009). Defying some difficulties of the assessment of several generic competences. Active Learning for Engineering Education (ALE). [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y., Tang, L., Le, H., Shen, K., Tan, S., Zhao, Y., Shen, Y., Li, X., & Gašević, D. (2024). Beware of metacognitive laziness: Effects of generative artificial intelligence on learning motivation, processes, and performance. British Journal of Educational Technology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D., Villa, S., Nicholls, S., Haavisto, O., Buschek, D., Schmidt, A., Kosch, T., Shen, C., & Welsch, R. (2024). AI makes you smarter, but none the wiser: The disconnect between performance and metacognition. arXiv, arXiv:2409.16708. [Google Scholar]

- Field, J. (2000). Lifelong learning and the new educational order. Trentham Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fiskerstrand, P., & Gamlem, S. M. (2023). Instructional feedback to support self-regulated writing in primary school. In Frontiers in education (Vol. 8, p. 1232529). Frontiers Media SA. [Google Scholar]

- Jossberger, H., Brand-Gruwel, S., Boshuizen, H., & Van de Wiel, M. (2010). The challenge of self-directed and self-regulated learning in vocational education: A theoretical analysis and synthesis of requirements. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 62(4), 415–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käis, J. (1992). Isetegevus ja individuaalne tööviis. 2. trükk. Koolibri. [Google Scholar]

- Kistner, S., Rakoczy, K., Otto, B., Dignath-van Ewijk, C., Büttner, G., & Klieme, E. (2010). Promotion of self-regulated learning in classrooms: Investigating frequency, quality, and consequences for student performance. Metacognition and Learning, 5, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laak, K. J., Abdelghani, R., & Aru, J. (2024). Personalisation is not Guaranteed: The Challenges of Using Generative AI for Personalised Learning. In International conference on innovative technologies and learning (pp. 40–49). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laak, K. J., & Aru, J. (2024). AI and personalized learning: Bridging the gap with modern educational goals. arXiv, arXiv:2404.02798. [Google Scholar]

- Ley, K. (2004, August 4–6). Motivating the distant learner to be a self-directed learner [Conference session]. 20th Annual Conference on Distance Learning and Teaching, Madison, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, S., Al-Hawamleh, A., Alazemi, A., Al-Jamal, D., Shdaifat, S. A., & Rezaei-Gashti, Z. (2022). Online learning and self-regulation strategies: Learning guides matter. Education Research International, 2022(1), 4175854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- McClelland, M. M., Cameron, C. E., Connor, C. M., Farris, C. L., Jewkes, A. M., & Morrison, F. J. (2007). Links between behavioral regulation and preschoolers’ literacy, vocabulary, and math skills. Developmental Psychology, 43(4), 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molenaar, I. (2022). Towards hybrid human-AI learning technologies. European Journal of Education, 57(4), 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, F. J., Ponitz, C. C., & McClelland, M. M. (2010). Self-regulation and academic achievement in the transition to school. In S. D. Calkins, & M. A. Bell (Eds.), Child development at the intersection of emotion and cognition (pp. 203–224). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevalainen, V., Juvonen-Nihtinen, M., & Lappalainen, U. (2004). Ajattelu ja ongelmanratkaisu. In T. A. Teoksessa, T. Siiskonen, & T. Aro (Eds.), Sanat sekaisin: Kielelliset oppimisvaikeudet ja opetus kouluiässä (pp. 122–149). PS-Kustannus. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 results (volume I): What students know and can do. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 results (volume I): The state of learning and equity in education. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, S. G., & Turner, J. C. (1994). Situated motivation. In P. Pintrich, D. Brown, & C. Weinstein (Eds.), Student motivation, cognition, and learning: Essays in honor of Wilbert J. McKeachie (pp. 213–237). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, N. E. (1998). Young children’s self-regulated learning and the contexts that support it. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(4), 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, N. E., Lisaingo, S., Yee, N., Parent, N., Wan, X., & Muis, K. (2020). Collaborating with teachers to design and implement assessments for self-regulated learning in the context of authentic classroom writing tasks. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 27(4), 416–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, N. E., & VandeKamp, K. J. (2000). Creating classroom contexts that support young children’s development of self-regulated learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 33(7–8), 821–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, N. E., VandeKamp, K. O., Mercer, L. K., & Nordby, C. J. (2002). Investigating teacher-student interactions that foster self-regulated learning. Educational Psychologist, 37(1), 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poom-Valickis, K., Jõgi, A. L., Timoštšuk, I., & Oja, A. (2016). Õpetajate juhendamispraktika seosed õpilaste kaasatusega õppimisse I ja III kooliastme tundides. Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri. Estonian Journal of Education, 4(1), 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, J., Reeves, B. N., Leinonen, J., MacNeil, S., Randrianasolo, A. S., Becker, B. A., Kimmel, B., Wright, J., & Briggs, B. (2024). The widening gap: The benefits and harms of generative ai for novice programmers. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM conference on international computing education research-volume 1 (pp. 469–486). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, K., & Leijen, Ä. (2014). Distinguishing self-directed and self-regulated learning and measuring them in the e-learning context. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 112, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sins, P., de Leeuw, R., de Brouwer, J., & Vrieling-Teunter, E. (2024). Promoting explicit instruction of strategies for self-regulated learning: Evaluating a teacher professional development program in primary education. Metacognition and Learning, 19(1), 215–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R. E. (2018). Educational psychology: Theory and practice. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Timoštšuk, I., Uppin, H., & Näkk, A. M. (2020). Kogemusõpe avatud õppekeskkonnas. SA Eesti Teadusagentuur. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unt, I. (1966). Õpilaste iseseisev töö tunnis. Valgus. [Google Scholar]

- Vandevelde, S., Vandenbussche, L., & Van Keer, H. (2012). Stimulating self-regulated learning in primary education: Encouraging versus hampering factors for teachers. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 1562–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vihalemm, T. (2014). Vaatlus. In K. Rootalu, V. Kalmus, A. Masso, & T. Vihalemm (Eds.), Sotsiaalse analüüsi meetodite ja metodoloogia õpibaas. Available online: https://samm.ut.ee/vaatlus (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Wang, K. D., Wu, Z., Tufts, L. N., II, Wieman, C., Salehi, S., & Haber, N. (2024). Scaffold or crutch? Examining college students’ use and views of generative ai tools for STEM education. arXiv, arXiv:2412.02653. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–40). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Challenge control | Supporting self-regulation by allowing students to control learning difficulty, pace, and task choice |

| Choice option | Allowing choices in learning fosters motivation, engagement, and responsibility |

| Self- and peer assessment | Encouraging autonomy by helping students set realistic goals and self-assess progress |

| Instrumental support from teacher and peers | Teacher guidance in cognitive and metacognitive skills through strategic instruction |

| Teachers’ evaluation practises | Formative feedback focused on personal growth and learning from mistakes |

| School | Teacher Pseudonym | Years of Teaching Experience | Grade Under Observation | Number of Students per Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Teacher A | 7 | 2nd | 21 |

| I | Teacher B | 4 | 2nd | 20 |

| II | Teacher C | 7 | 1st | 17 |

| Teacher | Grade | Number of Days of Use of Learning Guides per School Week | Number of Learning Guides Used | Whole Day/ Subject-Based Learning Guide |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2nd | 4 | 4 | 1/3 |

| B | 2nd | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| C | 1st | 1 | 6 | 6 |

| Category/ID | Description of Activities |

|---|---|

| Choice option | What, where, when, and with whom to learn, but also the choice of the learning method and material, the final format of the work, and the sequence of activities. |

| Challenge control | The possibility to choose the difficulty of the task, the pace, and the volume of the task. Students can choose the resources that match their interests and skills to the learning objectives. Students can check their performance by solving open-ended tasks with multiple pathways and options. Examples of open-ended tasks are problem-solving tasks, essays, projects, and tasks with no single correct answer. |

| Self- and peer assessment | Assessing personal development, giving feedback to others, evaluating the feelings and actions of others, self-assessment both during and at the end of the learning process in order to make corrections if necessary, self-testing, and self-checking. |

| Instrumental support from teacher and peers | The teacher engages students in discussions about thinking and learning processes; guiding questions are asked to encourage learners to reflect on their own learning activities; and they are guided to find their own answers or solutions themselves. Support provided through modelling (e.g., the teacher demonstrates the sequence of actions needed to complete a task) gives students the opportunity to see successful actions and task performance. The teacher guides students to cooperate, support, and teach each other. Students ask each other for help and are prepared to spontaneously support their peers. Learners share ideas, teach each other, and discuss problem-solving strategies. |

| Teachers’ evaluation practises | Evaluation practises that create a safe learning environment and foster intrinsic learner motivation, e.g., by integrating assessment and feedback into ongoing activities, holding students accountable without punishment, and encouraging them to focus on personal development, set goals and treat mistakes as learning opportunities. Feedback is formative, descriptive, and task-specific; it focuses on the learning process so that students can identify and narrow the gap between current performance and targets. Teacher messages relate to effort and the use of effective learning strategies, emphasise progress, and challenge and express confidence in students’ abilities. |

| Category | Observed Activities |

|---|---|

| Choice option | Task selection |

| Task completion order | |

| Task completion pace | |

| Learning companion | |

| Learning location | |

| Challenge control | Task difficulty level |

| Supplementary task selection | |

| Interest-based tasks | |

| Open-ended tasks | |

| Self- and peer assessment | Self-check with checklists |

| Discussion with teacher | |

| Automatic digital feedback | |

| Diary reflection | |

| Peer assessment | |

| Instrumental support from teacher and peers | Guidance in choice making |

| Teacher and peer support | |

| Encouragement to take on more challenging tasks | |

| Teachers’ evaluation practises | Verbal and group reflections |

| Goal setting | |

| Ongoing guidance | |

| Learning from mistakes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kersna, L.; Laak, K.-J.; Lepp, L.; Pedaste, M. Supporting Self-Regulated Learning in Primary Education: Using Written Learning Guides in the Lessons. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010060

Kersna L, Laak K-J, Lepp L, Pedaste M. Supporting Self-Regulated Learning in Primary Education: Using Written Learning Guides in the Lessons. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleKersna, Liina, Kristjan-Julius Laak, Liina Lepp, and Margus Pedaste. 2025. "Supporting Self-Regulated Learning in Primary Education: Using Written Learning Guides in the Lessons" Education Sciences 15, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010060

APA StyleKersna, L., Laak, K.-J., Lepp, L., & Pedaste, M. (2025). Supporting Self-Regulated Learning in Primary Education: Using Written Learning Guides in the Lessons. Education Sciences, 15(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010060