Abstract

This study investigates the mediating role of intellectual curiosity (IC) in the relationship between teacher–student relationship quality (TSR) and science achievement among Emirati early adolescents. The objectives were to assess TSR’s predictive power on science achievement, evaluate IC’s impact on science achievement, examine the combined effect of TSR and IC, and investigate IC’s mediating role. Data from 17,475 valid cases in the PISA dataset were analyzed using Jeremy Hayes’ PROCESS macro, multiple regression models, and bootstrapping with 5000 resamples. The results indicated that TSR significantly and directly affects IC, which in turn positively influences science achievement. TSR’s direct effects on science achievement varied across cases, but IC consistently showed strong positive effects on science achievement, underscoring its critical role as a predictor of academic success. IC was found to significantly mediate the relationship between TSR and student performance. The findings suggest that enhancing both TSR and IC is essential for student success in science. The study’s implications for educational practices and policies include developing teacher training programs focused on building strong relationships with students and fostering intellectual curiosity through questioning and problem-solving. Specifically, educators should focus on skills and strategies for interacting with students, showing empathy, and forming strong relationships. Implementing ongoing practices that emphasize the intellectual aspects of learning can help students build curiosity, thereby improving their academic performance. The study provides valuable insights into the interactions between TSR and IC and their impact on students’ academic outcomes.

1. Introduction

Science thinking involves belief, curiosity, imagination, reasoning, cause-and-effect links, self-examination and skepticism, objectivity, and open-heartedness [1]. Science requires curiosity, which motivates active learning and spontaneous discovery [2]. Curiosity fosters learning, insight, and innovation for individuals and society [3,4,5]. Teachers must spark pupils’ interest and encourage learning. Tao et al. [6] assert that social support is a crucial factor for students’ academic achievement. Other scholars, such as Dwyer and Cummings [7], explain that support from family, friends, and school staff, characterized by acceptance and emotional warmth, is associated with academic achievement.

Nevertheless, the quality of teacher–student relationships (TSRs) is a critical component of the educational process, significantly impacting students’ academic achievement and overall learning experience. Positive TSR, characterized by effective communication, support, and sensitivity to students’ needs, enhances academic performance [8]. However, the mechanisms through which TSR influences academic outcomes, particularly in the context of science education, are not fully understood. Intellectual curiosity (IC), defined as the desire for new information and experiences that trigger exploration and problem-solving [9], has emerged as a crucial intrinsic motivator that drives academic success [1,10].

Given the recognized impact of both TSR and IC on academic performance, there is a need to explore the potential mediating role of IC in the relationship between TSR and student achievement in science. This study aims to investigate how TSR and IC collectively influence science achievement among Emirati early adolescents, with a particular focus on whether IC mediates the relationship between TSR and science achievement. Understanding these dynamics could provide valuable insights for developing effective educational strategies that enhance student engagement and performance in science [11].

Therefore, the objectives of this study are to determine the extent to which teacher–student relationship quality predicts science achievement in Emirati early adolescents, to assess how IC predicts science achievement in the same demographic, to evaluate the combined predictive power of TSR quality and IC on science achievement, and to explore the mediating role of IC in the relationship between TSR quality and science achievement among Emirati early adolescents.

2. Research Design

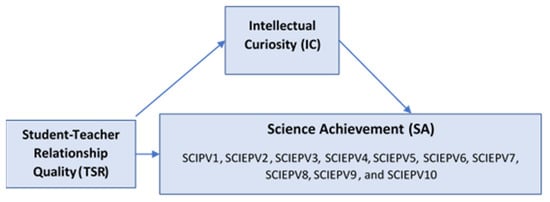

The study employs a comprehensive research design to investigate these relationships, utilizing data collected from Emirati teachers and students. The analysis involves examining the direct and indirect effects of TSR quality on science achievement, with IC acting as a mediator, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research design.

3. Intellectual Curiosity

As stated by Jones and Flint [9], curiosity refers to the inclination towards seeking new information or experiences that elicit responses such as investigation, the utilization of knowledge, or the development of new media skills, leading to either the fulfillment of curiosity or the withdrawal of persons from situations that provoke curiosity. Intellectual curiosity, also known as epistemic, information-seeking, or cognitive curiosity, is the state in which a kid actively produces specific problems and actively seeks resolutions and explanations for the topics that pique their interest [12]. Curiosity has been acknowledged as a prominent motivating factor that underlies and impacts both positive and negative human behavior [13].

Curiosity is a mindset and behavior that actively strive to gain a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of what is being learnt, and serves as a motivating factor for learning. Ref. [14] identified three dimensions of curiosity: social curiosity, epistemic curiosity, and perceptual curiosity. The desire to engage can be identified by two factors: having a genuine interest in the subject matter being taught and displaying curiosity about the upcoming information. The manifestation of curiosity is the act of posing inquiries regarding educational content. The manifestation of a desire to comprehend is the act of making inquiries in order to discover solutions to inquiries regarding educational information. According to Weible and Zimmerman [15], individuals that demonstrate curiosity when engaging in scientific activities develop their scientific identity by actively investigating, questioning, and manipulating, particularly when they collaborate with others. Thus, curiosity indicators encompass traits such as investigation, discovery, adventurousness, and questioning [16]. Grossnickle [17] asserts that curiosity is enhanced by a regulatory system that encompasses inquiry, questioning, and the yearning to uncover the unknown.

4. Teacher–Student Relationship Quality

Teacher–student relationships are a critical component of the educational process, significantly impacting students’ academic achievement and overall learning experience. These relationships, built on mutual respect, trust, and effective communication, can influence various educational outcomes. Göktaş and Kaya [8] found that positive teacher–student relationships have a medium-sized positive effect on academic achievement, underscoring the importance of both intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships.

Hajovsky, Mason, and McCune [18] noted that teacher–student closeness and conflict influence math and reading achievement, revealing the dynamic nature of these relationships. Curiosity also plays a crucial role, as Amorim et al. [11] found that curiosity and grade level predict the quality of teacher–student relationships. Nurishlah, Budiman, and Yulindrasari [10] emphasized that curiosity serves as a critical intrinsic motivator for students from low socioeconomic backgrounds, driving them to achieve high academic standards. Overall, the literature demonstrates that high-quality teacher–student relationships, characterized by effective communication, support, and sensitivity to students’ needs, positively influence academic performance and foster a more engaging and productive learning environment [8,10].

5. Science Achievement

Science achievement in PISA 2022 Academic achievement in educational institutions, including schools, colleges, and universities, refers to the measurable results that indicate the level of development individuals have made in specific educational objectives or activities [19]. The science achievement test in PISA focuses on scientific literacy. According to OECD [20], scientific literacy in PISA refers to “the ability to engage with science-related issues, and with the ideas of science, as a reflective citizen”. The science achievement test in PISA follows a framework that outlines three dimensions: knowledge, processes, and contexts [21]. In addition, the science achievement test assesses skills such as identifying scientific issues, explaining phenomena, interpreting data and evidence, and understanding scientific inquiry. The following outlines the importance of assessing science achievement in PISA:

- Using the science achievement test results give opportunities to countries to identify the strengths and areas for improvement and compare and benchmarking their educational system to the international standards.

- Using science achievement test results to enhance the science education by informing policy and practice.

- Informing countries on how well their students are prepared for the challenges in the scientific field.

6. PISA

PISA is a triennial survey of the knowledge and skills of 15-year-olds. It is the product of collaboration between participating countries and economies through the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and draws on leading international expertise to develop valid comparisons across countries and cultures. More than 400,000 students from 57 countries, making up close to 90% of the world economy, took part in PISA 2006. The focus was on science, but the assessment also included reading and mathematics and collected data on student, family, and institutional factors that could help to explain differences in performance.

7. Literature Review

7.1. Teacher–Student Relationships and Curiosity

Understanding the ways in which teacher–student relationships (TSRs) influence student outcomes, particularly intellectual curiosity (IC), is one of the most important areas of educational research. Specifically, the purpose of the research that Amorim et al. [11] carried out was to investigate the distinct contributions that curiosity and demographics provide to TSR. In addition to this, it aimed to determine the typical obstacles that teachers encounter while attempting to create meaningful relationships with their students. Over the course of the research project, 518 public school teachers from all over the United States participated by filling out an online survey. The results of the study showed that curiosity and grade level are important predictors of TSR. Students’ negative conduct, time limits, huge class sizes, family concerns, and absences were listed as some of the obstacles that prevented beneficial TSR from occurring. The discussion of the study brought to light the theoretical and practical consequences for educators and school administrators. It emphasized the necessity of addressing these barriers in order to improve the relationships between teachers and students and, as a result, to increase the intellectual curiosity of students.

Göktaş and Kaya [8] calculated TSR’s impact on student achievement using second-order meta-analysis. They distinguished intrapersonal and interpersonal teacher relationships. The impact of favorable interpersonal relationships (teacher–school community social links) on academic achievement was medium to large, whereas positive intrapersonal relationships (teachers’ inner lives and ideas) were moderate. Poor teacher–student relationships hinder academic achievement modestly to dramatically. This long study indicates that TSR strongly affects student performance, proving that healthy teacher–student relationships are crucial to academic success.

7.2. Curiosity and Science Achievement

Curiosity has been identified as a crucial factor in academic achievement, particularly for students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Nurishlah et al. [10] investigated the role of curiosity in motivating students with limited access to learning facilities. Their literature-based research pinpointed several factors that influence students’ curiosity, including the availability of learning resources, parental stimulation and feedback, and the classroom environment. The study underscored the importance of curiosity as an intrinsic motivator, driving students to excel academically despite socioeconomic challenges. It highlighted the need for educational strategies that foster curiosity through teacher stimulation, peer interactions, and student engagement in learning activities.

Herianto and Wilujeng [1] focused on the correlation between curiosity and generic science skills in junior high school students. Using a quantitative approach, they found that curiosity has a low positive correlation with generic science skills, accounting for 15.1% of the variance. This study demonstrated that while curiosity is a significant predictor of science skills, other factors also play a role. The research suggested the necessity for educational interventions that promote curiosity to enhance students’ scientific abilities. In a different context, Banupriya and Rajan [22] examined the relationship between curiosity, happiness, and academic achievement among high school students. Their study involved 200 students from private schools in Chennai, who completed several standardized inventories and scales. The results showed no significant correlation between academic achievement and curiosity; however, curiosity and happiness were significantly correlated. This finding suggests that while curiosity alone may not directly impact academic performance, it is closely linked to students’ overall well-being, which can indirectly influence their academic success.

7.3. Teacher–Student Relationships and Science Achievement

The influence of TSR on academic achievement has been the subject of extensive research. Göktaş and Kaya [8] conducted a second-order meta-analysis to determine the correlational effect sizes between TSR and student academic achievement. They categorized teacher relationships into intrapersonal and interpersonal types. The findings indicated that positive intrapersonal relationships (teacher’s inner life and thoughts) had a small positive effect on academic achievement, while positive interpersonal relationships (social links between teacher and school community) had a medium to very large positive effect. Negative teacher–student relationships, on the other hand, were found to have small to medium negative effects on academic achievement. This comprehensive analysis highlights the significant impact of TSR on student performance, suggesting that fostering positive teacher relationships within the school community is crucial for academic success.

In a longitudinal study, Hajovsky, Mason, and McCune [18] examined the quality of TSR and its impact on academic achievement in elementary school, with a focus on gender differences. The study utilized multiple group longitudinal cross-lagged panel models to explore the directional influences between teacher–student closeness, conflict, and academic achievement in math and reading. The findings revealed that teacher–student closeness decreased over time for both genders, while conflict increased for males. Math and reading achievement had medium reciprocal effects, meaning that previous academic performance influenced TSR quality and vice versa. However, once previous levels were controlled, TSR quality did not significantly impact subsequent academic achievement. This study underscores the complexity of TSR dynamics and their varied impacts on academic outcomes over time and across genders.

The importance of these findings lies in their implications for educational practices and policies. Firstly, the consistent positive relationship between TSR and IC highlights the need for educational strategies that prioritize building strong, supportive relationships between teachers and students. Teacher training programs focused on communication, empathy, and relationship-building skills could be vital in achieving this goal. By fostering environments where students feel supported and understood, educators can stimulate intellectual curiosity, which is crucial for academic success [23]. Furthermore, since IC is a strong predictor of academic success, educational initiatives should aim to cultivate curiosity through inquiry-based learning, problem-solving activities, and encouraging students to explore their interests. These approaches can help maintain high levels of student engagement and motivation, particularly among those from low socioeconomic backgrounds who might otherwise lack access to stimulating educational resources. The variability in the direct impact of TSR on academic achievement suggests that context-specific factors need to be considered. Tailoring interventions to the unique cultural, social, and educational environments of different student populations can enhance the effectiveness of these strategies. Understanding the specific needs and challenges of various student groups allows for more targeted and impactful educational practices.

8. Method

This research used a secondary data source, which is the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). After identifying the research design that shapes the relationships between the variables, the procedure involved extracting relevant items that form the construct of each variable from the PISA database, specifically focusing on the measure related to these variables “the quality of the teacher–student relationship and intellectual curiosity”. The research used the accessed PISA’s publicly available datasets, selecting items (questions inside the questionnaire) from the student questionnaires that pertained to these constructs. The selected items were then coded and analyzed using descriptive statistics to summarize the findings.

The PISA database was used to assess Emirati teachers’ intellectual curiosity, teacher–student relationship quality, and science achievement. Data from the PISA database was carefully extracted. Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 show the different items for these variables.

Table 1.

Teacher–student relationship quality items with codings.

Table 2.

Intellectual curiosity.

Table 3.

Plausible values in science.

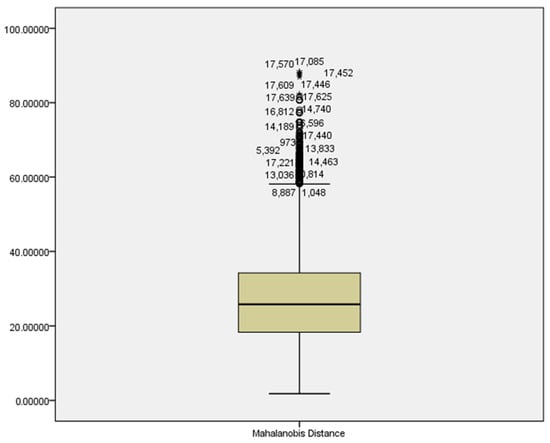

Complete screening was started to ensure data accuracy and usability. In total, 17,475 cases were valid for analysis after deleting 2022 cases due to missing values, 4848 univariate outliers, and 255 multivariate outliers as extremes based on Mahalanobis distance larger than 58; see Figure 2. Hays’ PROCESS macro analyzed the data. Multiple regression evaluated direct and indirect effects using Hayes’ ideas. Bootstrapping with 5000 resamples for mediation effect confidence intervals improved the study.

Figure 2.

Mahalanobis distance.

9. Results

The results of this study examine the direct and indirect effects of teacher–student relationship quality (TSR) on science achievement among Emirati students, with intellectual curiosity (IC) as a mediating factor.

9.1. Direct Effects

Table 4 indicates how intellectual curiosity mediates the effect of teacher–student relationship quality (TSR) on Emirati student achievement (PVSCIE), which refers to the academic performance, learning, and educational outcomes of students from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) who participated in this international standardized assessment (PISA 2022). TSR always affects IC directly, with a coefficient of 0.1444 and a p-value of 0.0000. Effective teacher–student relationships spark intellectual curiosity. This high relevance across all matrices suggests a robust TSR-IC relationship. PVSCIE is affected by TSR to variable degrees. Significant positive effects of TSR on PVSCIE were observed in Matrix 2 (β = 8.6056, p = 0.0045), Matrix 4 (β = 7.2695, p = 0.0147), Matrix 6 (β = 7.6051, p = 0.0124), Matrix 7 (β = 8.1722, p = 0.0066), and Matrix 8 (β = 6). Non-significant effects were seen in Matrix 1 (β = 5.5950, p = 0.0602), Matrix 3 (β = 3.8833, p = 0.1885), Matrix 5 (β = 1.2559, p = 0.6795), and Matrices 9 and 10 (β = 3.7518, p=0.2153). This means that TSR usually boosts student achievement, but its effects differ. IC significantly affects PVSCIE in all matrices, with coefficients ranging from β = 32.3820 (SE = 2.9929, t = 10.8195, p = 0.0000) to β = 44.1056 (SE = 3.0701, t = 14.3661, p = 0.0000). Intellectual curiosity consistently predicts student achievement, suggesting that cultivating it could boost academic performance. R values range from 0.0845 to 0.1464.

Table 4.

Direct effects.

Model fit indices show moderate correlation. Models explain just a small portion of PVSCIE variance, with R2 values of 0.0071 to 0.0214. The F-values of all models are significant (p = 0.0000). The data demonstrate that TSR and IC significantly impact Emirati student achievement. TSR’s direct influence on student achievement varies, but its indirect effect through IC is always significant. This implies that teacher–student relationships can enhance student achievement and intellectual curiosity. Teacher–student interactions and intellectual interest may boost UAE student performance.

9.2. Indirect Effects (Mediation)

Table 5 indicates how teacher–student relationship quality (TSR) affects Emirati student achievement (PVSCIE) through intellectual curiosity. Matrix 1 indicates an indirect influence of TSR on PVSCIE (β = 4.6988, BootSE = 0.4971, BootLLCI: 3.7573, BootULCI: 5.6801). The confidence interval does not include 0 in this situation, indicating that IC strongly mediates the TSR-PVSCIE relationship. An even higher indirect effect is shown in model 2 (β = 6.3707, BootSE = 0.5487). This suggests that intellectual curiosity mediates the association between teacher–student ratios and student achievement (BootLLCI = 5.3323, BootULCI = 7.4947, excluding zero).

Table 5.

Indirect effects.

As in Matrix 3, the indirect impact is β = 4.6773, with BootSE = 3.7243 (BootLLCI 5.6462, BootULCI 4897). This large mediation effect suggests that intellectual curiosity mediates teacher–student ties to accomplishment, as shown by the other five matrices. The indirect effect of β = 5.1830 is shown in Matrix 4 with BootSE = 4.1952 (2.2913, 5.7162). 6.1858. The non-zero confidence interval proves that intellectual curiosity has a mediating role.

Matrix 5: β = 5.8468, BootSE = 1, BootLLCI = 4.8535, BootULCI = 6.9598.

This strong indirect effect suggests that intellectual curiosity can improve student learning by increasing teacher–student connections. Indirect effect from β = 5.0628 in Matrix 6 with BootSE (→). 5038. A recent BootLLCI of 4.0943 and BootULCI of 6.0775 could establish another strong mediation effect. This emphasizes intellectual curiosity’s role in TSR and PVSCIE. For the indirect impact in Matrix 7, β = 5.7129, with BootSE = 534, Lower-Dependent BootLLCI = 4.6911, and Lower-Dependent BootULCI = 6.8051. The high mediation impact of intellectual curiosity shows that curiosity is crucial to teacher–student relationships and student achievement.

Resampled = 5198. Matrix 8: Indirect effect of β = 5.1248, BootSE. BootLLCI = 4.1234 BootULCI = 6.1667. This shows that intellectual curiosity unlocked other benefits in both matrices. Matrix 9 showed a strong indirect effect (β = 5.7717, BootSE. 5297, BootLLCI 4.7389, BootULCI 6).

Finally, Matrix 10 shows an indirect effect of β = 5.7717 with BootSE = 5384. The study’s BootLLCI is 4.7517 and BootULCI is 6.9141, confirming IC’s mediating role. Intellectual curiosity plays a significant role in the correlation between teacher–student relationship quality and student achievement, as shown by the uniform and large indirect effects across all four matrices. This suggests that teacher–student engagement programs should also foster intellectual curiosity to boost student accomplishment.

In all matrices, TSR positively influences IC significantly, and IC, in turn, significantly influences each PVSCIE measure. The indirect effects of TSR on PVSCIE through IC are consistently significant, demonstrating mediation. However, the direct effects of TSR on PVSCIE vary, with some being non-significant.

9.3. Total Effect

A statistical method is used to combine direct and indirect effects to assess the significance of the total effect (βTotal). Total effect is calculated by aggregating direct and indirect effects (Equation (1)), and the confidence interval is calculated using the combined standard error (SETotal). In performing a mediation effect calculation, the combined standard error is computed, taking the square root of the sum of the direct standard error squared and indirect standard error squared (Equation (2)). Thereafter, the confidence interval for the total effect CITotal is constructed by adding and subtracting the product of combined standard error and critical value from the standard normal distribution, which is approximate 1.96 for 95% confidence level, from the total effect (Equation (3)). If the total effect confidence interval does not include 0, then the total effect is considered statistically significant. The following equations are used to perform the calculations

where z is the critical value from the standard normal distribution (for a 95% confidence interval, z ≈ 1.96).

βTotal = βDirect + βIndirect

SETotal = sqrt(SEDirect^2 + SEIndirect^2)

CITotal = βTotal ± (z * SETotal)

Table 6 shows the total effects after applying the calculation to all matrices, by combining both the direct and indirect effects, which highlights the overall impact of TSR on PVSCIE.

Table 6.

Total effect.

10. Discussion

This study examines the impact of teacher–student relationships (TSRs) on the academic performance of Emirati students in science (PVSCIE), with a specific emphasis on the function of intellectual curiosity (IC) as a mediator. Firstly, the study concludes that TSR had a considerable positive impact on IC in all the settings that were evaluated. The persistent positive correlation suggests that more robust and superior teacher–student interactions promote heightened intellectual curiosity in kids.

The analysis of the specific impact of TSR on “PVSCIE” indicates diverse results in different situations. On one hand, in some cases, TSR can have a substantial positive effect on the academic performance of students. Nevertheless, in other situations, not only does this effect not exist but it is not statistically significant either. Apparently, in most cases, TSR is correlated with a variety of improvements in the educational achievement of students. Still, its positive influence can vary depending on some situational or setting factors. In addition, the impact of IC on PVSCIE is consistently significant in all situations.

The indirect influence of TSR on PVSCIE via IC is highly significant in all examined scenarios. Such a strong mediating effect that appears in every sample confirms that intellectual curiosity is an efficient mechanism through which good teacher–student relationships affect student achievement. Thus, it is possible to contend that fostering intellectual curiosity is a critical way through which positive teacher–student interactions increase academic achievement. In the end, if both direct and indirect effects are considered, the overall effect of TSR on PVSCIE is significant in every situation.

The research conducted in the article has significant implications in the education field concerning the science achievement of Emirati students. The article demonstrates the effect of teacher–student relationships (TSRs) on intellectual curiosity and academic performance. However, as demonstrated by Amorim Neto et al. [11], curiosity that is highly determined by TSR is a key driver to the achievement of the results.

Previous research conducted by Göktaş and Kaya [8] has shown that TSR generally has a beneficial effect on academic accomplishment, but the impact can vary. However, this study reveals conflicting findings about the direct influence of TSR on science achievement (PVSCIE), indicating that the effects may depend on specific circumstances. Moreover, in line with the findings of Nurishlah et al. [10] and Herianto & Wilujeng [1], the present study emphasizes that IC is a robust indicator of academic achievement in all settings.

In the UAE context, where educational reform movements prioritize integrating global best practices with local cultural values, this study on teacher–student relationships (TSR), intellectual curiosity (IC), and science achievement among Emirati early adolescents is particularly relevant. At the professional level, there are four UAE teacher standards that guide all professional development opportunities, curriculum development, student learning design, and engagement. The first one, “Professional and ethical conduct,” emphasizes the role of values in shaping the dynamic learning environment on class levels, school levels, and also with the local community. It regulates the expected behaviors from teachers that attract students’ respect, trust, and motivation. For example, in this first standard, there are many explicit requests from teachers to “demonstrate integrity—to act honestly in professional relationships with individuals and organizations”, “demonstrate respect for cultural and other diversities within the school community”, “provide equal opportunities”, and “ensure physical, emotional and psychological wellbeing for learners” [10]. Therefore, these comprehensive regulations predict significant efforts to be exerted by teachers when forming relationships with their students to comply with the MOE requirements to be a UAE licensed teacher, as teacher licensure is a required item to join the teaching profession that is based on the teacher standards [24].

In terms of the student’s role and responsibility, Emirati society strongly emphasizes respect for educators and nurturing interpersonal connections, underscoring TSR’s potential to positively influence IC development. Emirati schools play a crucial role in enhancing students’ intrinsic motivation and engagement in science by fostering a supportive learning environment through effective TSR [25]. This approach aligns with the UAE’s aspirations for a knowledge-based economy and strengthens the foundation for lifelong learning and innovation among Emirati youth. Thus, understanding these dynamics contributes to refining educational strategies and pedagogies that are culturally responsive and impactful in the UAE context, which will ultimately affect students’ academic achievement [26,27]. Then, assuming that the basis of a motivational relationship is already formed between teachers and students, students’ intellectual curiosity will now foster deeper engagement with the subject matter. This curiosity-driven interaction encourages Emirati students to actively explore and question, aligning with educational goals to nurture critical thinking and innovation essential for future success [28].

11. Significance of These Findings

These findings are significant because they affect educational methodologies and policies. Since TSR and IC are consistently correlated, methods which call for the development of strong, healthy bonds between teachers and students appear to be crucial to ensure success. For example, developing training programs for teachers that would be aimed at enabling them to develop communication, empathy, and relationship-building skills can be considered as a feasible teaching intervention. Indeed, scholars are accredited to consistently show that IC is one of the strongest predictors of academic achievement, and efforts should be made to encourage inquisitiveness through the use of inquiry-based learning, solving problems tasks, and focusing on topics of their interest. It is also evident that, given the fluctuations in the direct impact of TSR on PVSCIE, the current study should be regarded as taking the first steps towards context-specific considerations. The target population should, therefore, be considered, and the strategies should be adjusted to address their specific cultural, social, and educational needs.

12. Significance of This Work

This work has a multifaceted and varied impact. On one hand, it brings a new understanding to the significance of both types of TSR and IC for the academic performance of students in science education and offers a clear and concise guideline to improving the education outcomes in the field. On the other hand, it can be used as an input for the decision-making processes of policy-makers, developing and implementing educational policies that contribute to the growth of teachers and the learning environments concentrating curiosity. Moreover, it also opens up new research paths, allowing for a better understanding of the factors influencing the efficiency of TSR in specific situations and, therefore, creating a setting for finding general ways to improve the education reception.

13. Conclusions

TSR considerably improves IC across settings, demonstrating that strong teacher–student interactions foster intellectual curiosity. TSR can boost academic achievement; however, its impact depends on the situation. However, IC consistently and significantly affects PVSCIE, demonstrating its mediator role. TSR’s indirect effect on PVSCIE via IC is strong in all scenarios, indicating that favorable teacher–student interactions stimulate intellectual curiosity and academic success.

Therefore, it can be suggested that fostering a positive teacher–student relationship is essential not only for nurturing curiosity but also for improving students’ academic outcomes. The research implications are particularly relevant in the UAE’s educational reform setting and context, emphasizing the need for pedagogical strategies that integrate strong teacher–student relationships, which was also strongly recommended by John Hattie and Yates [29], with culturally responsive practices. By aligning with UAE educational standards and societal values, these pedagogical strategies can enhance students’ intrinsic motivation and engagement, thereby impacting learning and achievement positively.

14. Limitations

The study’s focus on Emirati pupils may limit its applicability to other cultural or educational contexts, requiring confirmation in other settings. Unaccounted-for factors including socioeconomic position, family participation, and school resources could distort the results. The diversity in TSR’s direct impact on PVSCIE shows context-specific elements that may temper this relationship, underlining the need to uncover and better understand these moderating factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A. and O.A.K.; methodology, A.J.; software, O.A.K.; validation, N.A. and A.J.; formal analysis, A.J.; investigation, O.A.K.; resources, N.A.; data curation, N.A. and O.A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A., O.A.K. and A.J.; writing—review and editing, A.J.; visualization, O.A.K.; supervision, O.A.K.; project administration, A.J.; funding acquisition, N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in PISA 2022 dataset at https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets/pisa-2022-database.html, accessed on 3 July 2024. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: OECD https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets/pisa-2022-database.html.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Herianto, H.; Wilujeng, I. The Correlation between Students’ Curiosity and Generic Science Skills in Science Learning. J. Inov. Pendidik. IPA 2020, 6, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudeyer, P.Y.; Gottlieb, J.; Lopes, M. Intrinsic motivation, curiosity, and learning: Theory and applications in educational technologies. Prog. Brain Res. 2016, 229, 257–284. [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm, M. Promoting curiosity? Possibilities and pitfalls in science education. Sci. Educ. 2018, 27, 987–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, W.L. Cultivating Curiosity in K-12 Classrooms; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://books.google.ae/books?hl=en&lr=&id=uYvgEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP7&dq=Ostroff,+W.L.+Cultivating+curiosity+in+K-12+classrooms.+ASCD+2016+.&ots=jNeCe9xIU9&sig=mWU5DvsQ7ANjiysYFJnSL1ELWMw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Ostroff%2C%20W.L.%20Cultivating%20curiosity%20in%20K-12%20classrooms.%20ASCD%202016%20.&f=false (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Pluck, G.; Johnson, H. Stimulating curiosity to enhance learning. Educ. Sci. Psychol. 2011, 2, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Dong, Q.; Pratt, M.W.; Hunsberger, B.; Pancer, S.M. Social support: Relations to coping and adjustment during the transition to university in the People’s Republic of China. J. Adolesc. Res. 2000, 15, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, A.L.; Cummings, A.L. Stress, self-efficacy, social support, and coping strategies in university students. Can. J. Couns. Psychother. 2001, 35, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Göktaş, E.; Kaya, M. The Effects of Teacher Relationships on Student Academic Achievement: A Second Order Meta-Analysis. Particip. Educ. Res. 2023, 10, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.B.; Flint, L.J. The Creative Imperative: School Librarians and Teachers Cultivating Curiosity Together; Bloomsbury Publishing USA: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Laesti, N.; Budiman, N.; Yulindrasari, H. Expressions of Curiosity and Academic Achievement of the Students from Low Socioeconomic Backgrounds; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.; Carmo, R.D.; Golz, N.; Polega, M.; Stewart, D. The Impact of Curiosity on Teacher–Student Relationships. J. Educ. 2020, 202, 002205742094318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tahri, D.; Qiang, F. How does active learning pedagogy shape learner curiosity? A multi-site mediator study of learner engagement among 45,972 children. J. Intell. 2024, 12, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenaar-Golan, V.; Gutman, C. Curiosity and the cat: Teaching strategies that foster curiosity. Soc. Work. Groups 2013, 36, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reio, T., Jr.; Petrosko, J.; Wiswell, A.; Thongsukmag, J. The Measurement and Conceptualization of Curiosity. J. Genet. Psychol. 2006, 167, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weible, J.L.; Zimmerman, H.T. Science curiosity in learning environments: Developing an attitudinal scale for research in schools, homes, museums, and the community. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2016, 38, 1235–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raharja, S.; Wibhawa, M.R.; Lukas, S. Mengukur rasa ingin tahu siswa [measuring students’ curiosity]. Polyglot J. Ilm. 2018, 14, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossnickle, E.M. Disentangling curiosity: Dimensionality, definitions, and distinctions from interest in educational contexts. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 28, 23–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajovsky, D.B.; Mason, B.A.; McCune, L.A. Teacher-student relationship quality and academic achievement in elementary school: A longitudinal examination of gender differences. J. Sch. Psychol. 2017, 63, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, A.H. Factors that affect students’ academic achievement in the faculty of social science at the University of Bosaso, Garowe, Somalia. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 11, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. PISA 2015 Results (Volume V): Collaborative Problem Solving; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2024 Science Framework; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/pisa-2024-science-framework-6e8c04f6-en.htm (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Banupriya, V.; Rajan, M.R. Curiosity, happiness, and academic achievement among high school students. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2019, 7, 456–466. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, N.; Abu Khurma, O.; Afari, E.; Swe Khine, M. The Influence of Learning Environment to Students’ Non-Cognitive Outcomes: Looking through the PISA Lens. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2023, 19, em2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raising the Standard of Education—The Official Portal of the UAE Government. (n.d.). U.ae. Available online: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/leaving-no-one-behind/4qualityeducation/raising-the-standard-of-education (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Areepattamannil, S.; Abu Khurma, O.; Ali, N.; Alhakmani, R.; Kadbey, H. Examining the relationship between science motivational beliefs and science achievement in Emirati early adolescents through the lens of self-determination theory. Learn. Environ. Res. 2023, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, F.A. Culturally Responsive Pedagogies in Arizona and Latino Students’ Achievement. Teach. Coll. Rec. Voice Scholarsh. Educ. 2016, 118, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, T.; Hermond, D.; Vairez, M.R., Jr.; Larchin, L.; McCree, C. Culturally Responsive Classrooms: Closing the Achievement Gap. Int. J. Divers. Identities 2015, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.; Harbaugh, A.G.; Seider, S. Fostering adolescent curiosity through a question brainstorming intervention. J. Adolesc. 2019, 75, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattie, J.; Yates, G.C.R. Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).