1. Introduction

Since its release in November 2022, ChatGPT has become a popular tool for daily work and study [

1,

2]. Its powerful text-generation ability has made it extremely popular among college students, and some students have been found violating academic integrity policies by using ChatGPT [

3,

4]. Despite ongoing research on the automated detection of AI-generated texts [

5], it has been difficult for teachers or plagiarism detection tools to distinguish between the texts written by students themselves and the texts generated by ChatGPT [

6,

7,

8]. The easy access to ChatGPT and the difficulty in detecting its use have raised great ethical concerns about its misuse by students [

9,

10].

Therefore, educators and researchers have been devoted to better using this emergent AI tool to support teaching and learning, particularly for writing [

11]. For example, Strzelecki [

12] conducted a survey on Polish college students’ acceptance and use of ChatGPT; he found that the top three predictors of students’ intention to use ChatGPT are habit, performance expectancy, and hedonic motivation. Su et al. [

13] suggested potential approaches to integrating ChatGPT in argumentative writing classrooms, such as using ChatGPT to draft outlines, help with editing and proofreading, and facilitate post-writing reflection. However, at present, there is less research based on students’ hands-on experience of using AI/ChatGPT to complete course writing assignments. Given writing’s prominent place in post-secondary education, this study seeks to better understand how undergraduate students make use of AI technologies when they are encouraged, rather than discouraged, from doing so.

1.1. Literature Review

There has been an increasing body of literature on the use of ChatGPT to assist writing since 2023. Yet, the majority of the literature consists of conceptual papers or commentaries regarding the potential use of ChatGPT for teaching and learning from the perspective of educators and researchers [

11]. For example, Fontenelle-Tereshchuk [

14] reflected on an educator’s observations of high school students lacking preparation in academic writing when students transitioned to college during the COVID pandemic and brought up the concern that ChatGPT may hinder their improvement in critical thinking and writing skills. Halaweh [

15] discussed the general concerns about using ChatGPT in educational settings. To address the concern of harming the originality of ideas, the author proposed strategies for the use of ChatGPT in classrooms, such as making rules or guidelines on its use, putting them on the course syllabus, and having students document how they used it. Kohnke and colleagues [

16] summarized the strengths (e.g., supporting interactive language learning, providing adaptive responses according to the different language levels of users) and weaknesses (e.g., being used for cheating, lacking accuracy in its responses, being wordy and repetitive) of using ChatGPT for language teaching and learning based on their own explorations with ChatGPT.

There have been, however, fewer studies focused on students’ perceptions of the use of Generative AI. The studies that do exist have focused on students’ attitudes toward using ChatGPT or views of the general impact of ChatGPT on education. For instance, Khalaf [

17] investigated 131 Oman college students’ attitudes toward plagiarism using AI tools and traditional plagiarism without using any AI tools and found a significant correlation between the two. Farhi et al. [

18] also conducted a quantitative study by administering surveys to 388 university students in the United Arab Emirates and found that ChatGPT usage significantly affected students’ views, concerns, and perceived ethics. Firat [

19] recruited 21 online participants who were scholars or Ph.D. students in the educational field to respond to an open-ended question “What does ChatGPT mean for students and universities?” (p. 60). The qualitative analysis of participants’ responses identified themes such as the changing role of educators, enabling personalized learning, and impact on assessment and evaluation [

19]. Ngo [

20] investigated 200 Vietnamese university students’ perceptions of using ChatGPT for their learning in general, including the overall attitude toward ChatGPT’s applications, benefits, barriers, and concerns. Our study, in contrast, focused on a concrete use of Generative AI tools with a specific prompt for a writing assignment.

Although there is a rising trend of publications on empirical studies, only a small body of the literature is about empirical explorations of students’ use of ChatGPT for their writing. Among the few empirical studies we found, Yan [

21] reported the investigation of eight undergraduate students’ reflections on the use of ChatGPT for English writing based on a one-week writing workshop that included a total of 116 students in China. English was a second language for the students. In the interview, students identified (1) the power of ChatGPT, such as speedy generation, generally good quality, and academic writing readiness; (2) the risk of ChatGPT, such as inequity, replaced writing practices, and avoiding plagiarism detection; and (3) provided suggestions for proper use of ChatGPT in writing.

Another empirical study reported on an experimental design study that compared the learning results of 25 Chinese students who received ChatGPT-assisted writing instructions versus another 25 students who received traditional writing instructions [

22]. The duration of the two types of instructions was the same at 12 weeks. Pre/post-assessments showed that students in the ChatGPT group significantly improved their writing skills and writing motivation compared to the control group. The study also conducted individual interviews with nine students from the ChatGPT group on their perceptions of advantages, disadvantages, and challenges when writing assisted by ChatGPT.

1.2. Research Goal and Research Questions

Despite these few existing empirical studies, more research is needed in this emerging field to understand students’ perceptions of using Generative AI in educational settings. Therefore, we conducted this study to examine how students in advanced writing courses used AI (i.e., ChatGPT) to complete an assignment, guided by the following research questions.

What are the different ways that students write and revise prompts when they use ChatGPT?

What are students’ views of the strengths of ChatGPT for writing after they incorporated ChatGPT in writing assignments?

What are students’ views of the weaknesses of ChatGPT for writing after they incorporated ChatGPT in writing assignments?

How would students like to improve their use of ChatGPT for better writing?

What are students’ overall attitudes toward writing with ChatGPT?

2. Methods

2.1. Context and Participants

This study is part of a larger, ongoing research project that explores the use of Generative AI tools to support teaching and learning at the college level. Participants were recruited from three undergraduate classes of the same advanced-level writing course at a private university on the West Coast of the United States during the Fall 2023 semester. The three classes shared the same instructor.

The course, Advanced Writing for Natural Sciences, uses rhetorical theory to provide students the opportunity to practice and learn more about adapting their style, tone, and argumentation depending on the audience and genre. The three classes included a total of 57 students. Of the 57, 91% (n = 52) were seniors and 9% (n = 5) were juniors. In terms of their major of study, 19% (n = 11) were majoring in hard sciences, 19% (n = 11) in business or finance, 18% (n = 10) in arts, humanities, and media, 18% (n = 10) in computational or quantitative fields (i.e., data science), 12% (n = 7) in health sciences, 12% (n = 7) in social sciences, 11% (n = 6) in interdisciplinary fields, and 5% (n = 3) in engineering. (Note that some students had multiple majors, so these numbers would not add up to 57).

Students’ participation in the research was completely voluntary, and a total of 55 students consented to participate. According to the instructor’s records of students’ preferred gender pronouns, 51% of the students self-identified as female; 35% self-identified as male; and the remaining 14% did not identify. The racial/ethnical backgrounds of students in our study aligned with the university-wide statistics of student demographics in Fall 2023: 20% Asian, 6% Black/African American, 16% Hispanic, 23% White/Caucasian, 27% International, and 8% Other.

2.2. Research Design

The research design for this study followed a pre-experimental design, more specifically, a one-group post-treatment-only design [

23]. A single group of student participants received the treatment of completing a writing assignment (more details are provided in the following section) and then completed a post-assessment report.

2.3. Data Collection

During Week 2 of the semester, the instructor gave the three classes the same writing assignment, which asked them to first select a job posting or a graduate program and then draft a cover letter or personal statement, along with a resume or CV, depending on what their chosen prompt solicited. Students were required to create two versions of these documents: one human-generated and one AI-generated. Prior to this writing assignment, the instructor did not give any instructions on how to use AI tools for writing. In addition, to the best of the instructor’s knowledge, students did not have any prior experience of using AI tools for course writing assignments or receive any training on using AI tools for formal writing.

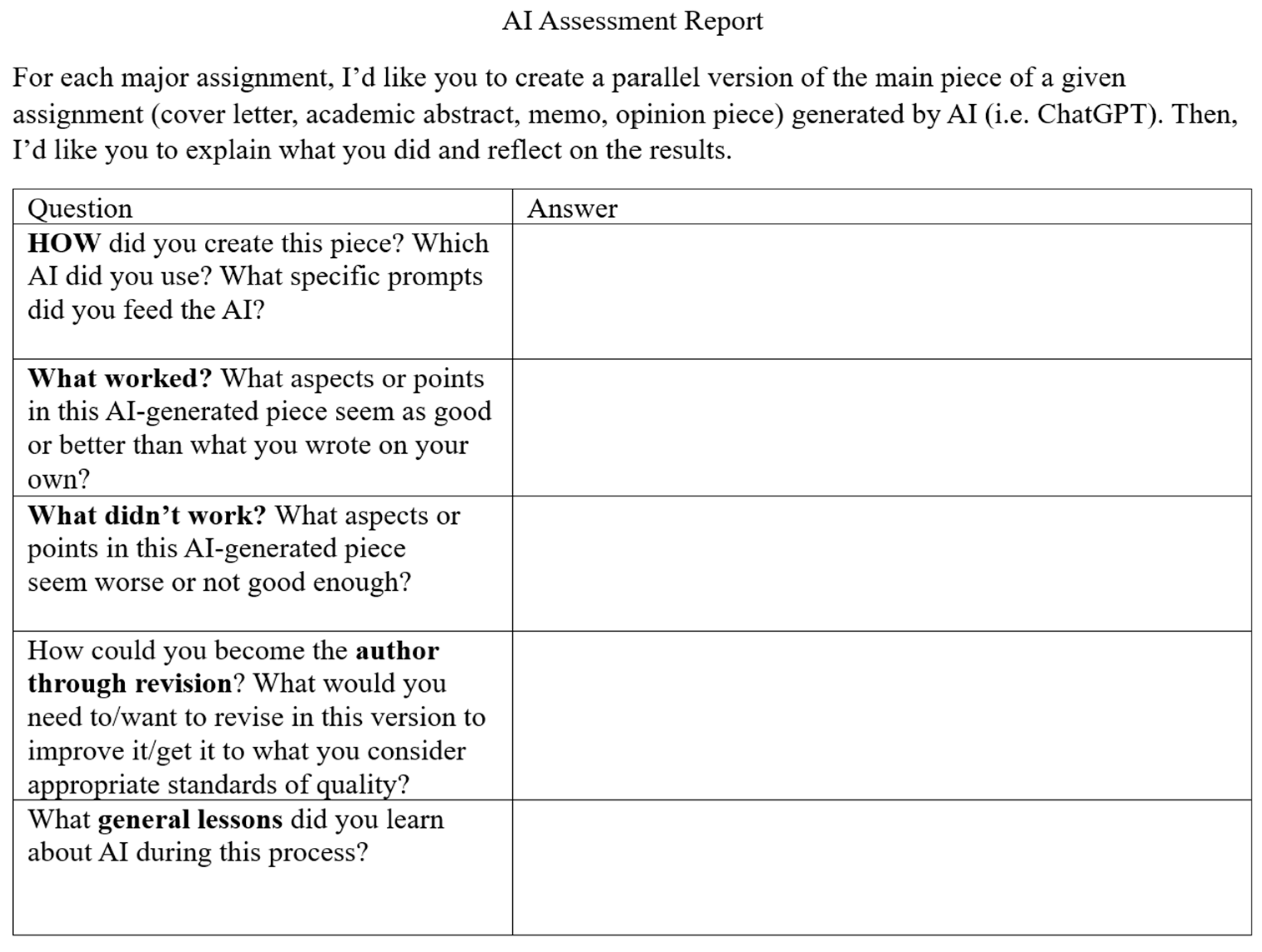

We collected our research data through an open-ended survey in the format of an “AI Assessment Report” embedded in the assignments for students who consented to participate in the study. We decided to use open-ended questions for the survey because the open-ended format allowed us to collect detailed information about students’ perceptions regarding their experience of the writing assignments. As one of the requirements for the assignment, the instructor asked students to complete the survey (i.e., AI Assessment Report) with reflections on their experience using Generative AI for this writing task (see

Figure 1). Finally, 47 students submitted their responses to the survey.

The survey consisted of five open-ended questions about their creation process, what worked, what did not work, how to better write with ChatGPT, and the general lessons learned. All the 47 students answered all the five questions.

Table 1 shows the minimum length, maximum length, average length, and standard deviation of all 47 students’ responses to each of the five questions. Student responses were anonymized. We use S1, S2, …, S47 to denote the 47 students.

The survey asked students to disclose which tools they used to create the AI-generated version of the assignment. Based on students’ responses, only one student used Bard Experiment (an early version of Google Gemini), while the other 46 students all used ChatGPT. Among the 46 who used ChatGPT, 89% of students (n = 41) did not specify a version; 4% of students (n = 2) specified that they used ChatGPT 3.5, and 4% (n = 2) specified that they used ChatGPT 4, the paid version.

2.4. Data Analysis

For Research Questions 1–4, we applied thematic analysis methods [

24] to analyze students’ responses to the first through fourth survey questions (Q1–Q4). We identified emergent themes from students’ responses, created a coding book, and manually coded each student’s responses to each question (using an Excel [Version 2408] spreadsheet). The final version of the coding book for Q1–Q4 after establishing coding reliability can be found in the

Supplementary Material.

The first author developed the coding schemes and coded them together with a research assistant. We started from Q2 and went through 2 iterations of independent coding, comparing results, discussing inconsistencies, and clarifying the coding scheme, until we reached a satisfactory percent agreement [

25]. In the first round, we each coded all students’ responses to Q2 and obtained 77.9% agreement on all codes; then, we discussed inconsistent codes and revised the coding scheme for better clarification; based on the revised coding scheme, we re-coded all the students’ responses and reached 84.2% agreement; finally, we discussed and resolved all inconsistent codes. Our second-round post-discussion results were used as the final coding results for RQ2. Then, the two coders moved on to Q3 by (1) independently coding all students’ responses; (2) comparing our codes and reaching a satisfactory agreement of 85.7% for the first round; and (3) discussing all inconsistencies and resolving 97% of them (only 2 codes remained inconsistent). Next, for Q4, the two coders first independently coded 16 students’ (odd-numbered students from S1 to S31) responses and reached a satisfactory agreement of 85.7%, so we discussed and resolved the inconsistent codes. Then, the main coder finished coding the remaining responses. Finally, we coded Q1 by following similar steps as how we coded Q4. The two coders first independently coded 16 students’ (even-numbered students from S2 to S32) responses and reached a satisfactory agreement of 96.4%. We discussed all inconsistencies and resolved 10 out of the 11 inconsistent codes. Then, the main coder finished coding the remaining responses.

For Research Question 5, we applied sentiment analysis to students’ responses to the fifth survey question from the Lexicon-based approach [

26,

27,

28]. The first author used the Python TextBlob package to perform the analysis. TextBlob was selected because it is well-acknowledged as a reliable tool for sentiment analysis [

29,

30]. The analysis result will generate a polarity value on the scale from −1 to 1 for each student’s response to Q5. The minimum value −1 represents the respondent’s attitude being extremely negative, and the maximum value 1 represents the respondent’s attitude being extremely positive. The magnitude of the value is positively related to the intensity of emotion.

3. Results

3.1. Creation Process and Prompts for ChatGPT

With regard to the creation process, 55% of students (n = 26) reported only one round of prompting ChatGPT to generate the writing piece, while 45% (n = 21) reported more than one round of prompting and having ChatGPT generated at least two versions of writing. For our analysis, the prompts used by students in their only round or their first round of prompting are called initial prompts, and the prompts for the second round or beyond are called revision prompts.

For the initial or only round, students provided different types of prompts, such as basic level, information from the resume, job description, what to highlight or focus on, length of the letter or statement, and emotion. Each student may have a unique combination of these different prompts.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of students for the different prompts. Overall, 32% of students (n = 15) provided a basic-level initial prompt that only briefly states their need to write an application letter (or a personal statement for some students) for which target position (or academic program). They provided no more than the resume information and the job description. For example, S43 provided his/her initial prompt to ChatGPT like this, “Please generate a personal statement for an undergraduate student who is looking to apply to Ph.D. programs in chemical biology”. And S12 wrote, “I used ChatGPT and used the prompt ‘Write a cover letter for the 2024 Intern—Technology at FTI Consulting. Here is the job posting:’ and then copied and pasted the job posting”.

Overall, 70% of students (n = 33) provided information from their resume or uploaded the resume file to ChatGPT. For example, S2 wrote, “I fed ChatGPT various bullet points from the most recent experience on my resume and asked it to convert these bullet points into a paragraph that I could use in my cover letter”. Twenty-two students provided the job description or the information about the target company/organization in the initial prompts. The earlier example by S12 is also an example of providing job information in the initial prompt.

More students (68%, n = 32) provided the initial prompts that went beyond the basic level. In total, 15% of students (n = 7) provided his/her personal information that is often not included in resumes. For example, S27 prompted ChatGPT about personal information like this, “Add the personal detail that I became interested in finance because I watched my father trade stocks when I was a child”. S25 told ChatGPT to “start the paper with a personal anecdote about when I went on a service trip in the Philippines to help Filipino children receive dental care for the first time”.

A total of 26% of students (n = 12) specifically asked ChatGPT to highlight which experience, quality, or anything particular in their initial prompts. S4 wrote, “highlighting skills in Python, machine learning, and data analytics”. S14 told ChatGPT to “create a one-page cover letter for the Deloitte audit intern position with emphasis on my experience as in an Accounting-Finance Rotation Program Intern at Disney and tutoring accounting courses”. A total of 15% of students (n = 7) explicitly requested ChatGPT to tie their experience(s) to the position. S2 wrote, “and then asking it to tie those experiences to the culture at the company that I was applying for”.

A total of 38% of students (n = 18) specified the length of the writing product, such as how many paragraphs, words, or pages. For example, S5 provided “Write me a cover letter in less than 400 words for a health research internship” and S6 prompted “Given the above prompt, write me a 2 page personal statement”. Overall, 17% of students (n = 8) asked ChatGPT to incorporate their emotions, such as interest, excitement, love, and enthusiasm, into the writing. Additionally, three students assigned a role for ChatGPT or set the tone for the writing. For example, S5 prompted, “You are a personal assistant who writes documents in a professional and corporate tone”.

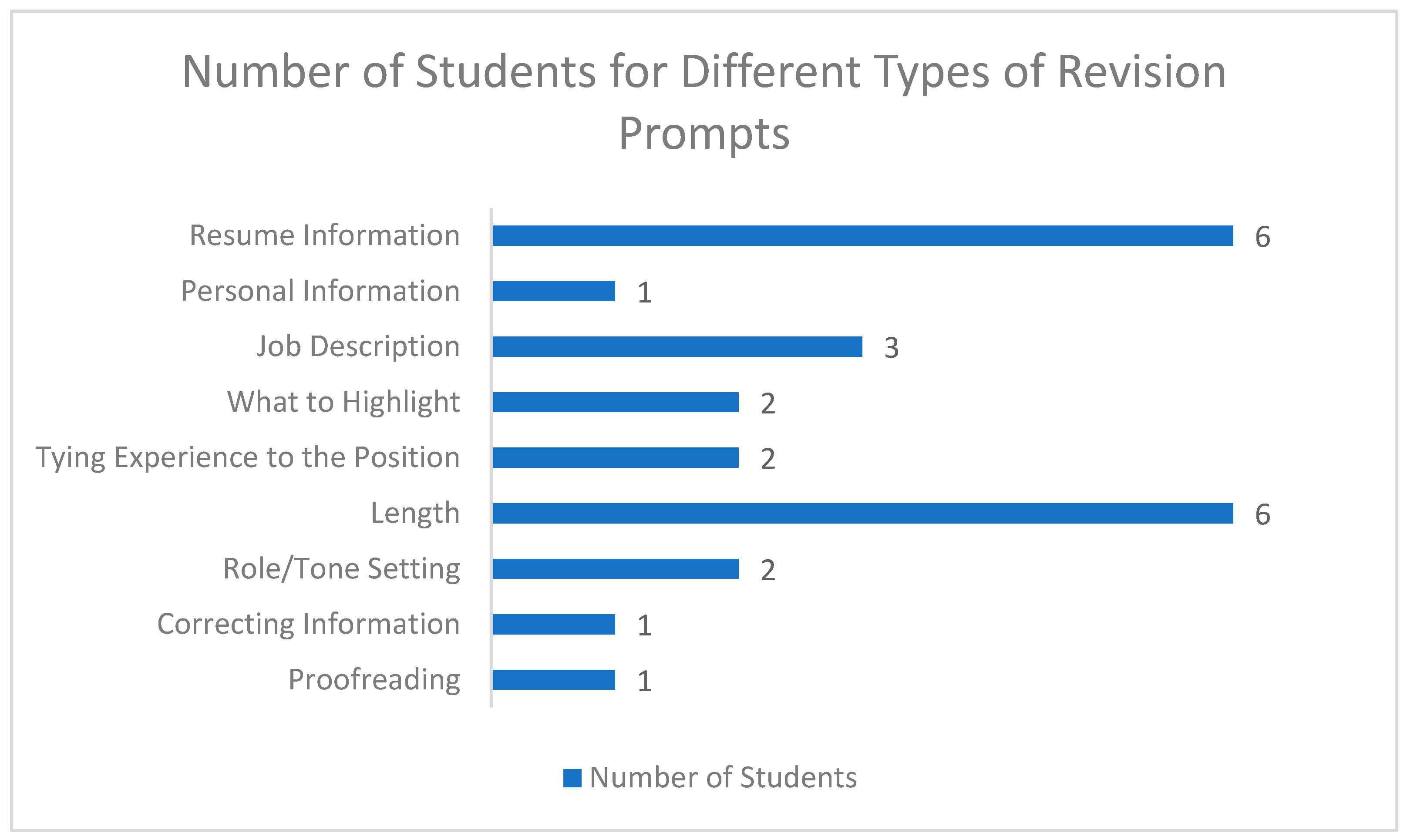

For the 21 students who provided revision prompts, the distribution for different types of revision prompts is shown in

Figure 3. Students revised the prompts according to the writing generated in the previous round, but most of the revision prompts fell into similar categories as in the initial prompts. In total, 29% of the 21 students (n = 6) included resume information in the revision prompts. For example, some students added more skills or experiences, and some uploaded their resumes to provide a more comprehensive picture of their professional qualifications if they did not do so in the initial prompts. A total of 29% of them (n = 6) specified length in revision prompts; 14% of them (n = 3) provided more information about job descriptions; 10% of them (n = 2) told ChatGPT what to highlight in the writing; 10% (n = 2) explicitly asked ChatGPT to tie the experience to the position; and 10% (n = 2) set the tone or assigned a role for ChatGPT in the writing task. There were also students who asked ChatGPT to correct some information that was made up in earlier writing (n = 1) and proofread the earlier version of writing (n = 1).

3.2. Strengths of ChatGPT

The coding results of Q2 are shown in a bar chart (

Figure 4). The majority of the 47 students (68%, n = 32) acknowledge that ChatGPT performed a good job in integrating and connecting personal experiences from their resumes to their application letters (i.e., Personal Touches), although the connection may be general and vague. For example, S2 wrote, “It was able to write a very good paragraph about my work experience based on the bullet points that I gave it from my resume”. For many students, ChatGPT can make meaningful connections that go beyond the general level. A total of 60% of students (n = 28) explicitly emphasized that ChatGPT closely connected the writing to the job description or the topic. For example, S6 wrote, “AI-generated piece was also extremely effective when it came to explaining how my background in architecture played into my ability to be a successful lawyer”.

The majority of students (66%, n = 31) pointed to template generation as another strength of ChatGPT for writing application letters. Students believe that the draft generated by ChatGPT can serve as a good starting point because it usually has a strong formulaic structure, has effective opening and concluding paragraphs, and keeps overall coherence throughout the piece. For example, S1 wrote, “It also had a nice concluding paragraph. It tied everything together well and made the piece seem complete”. S3 wrote, “I think the overall structure of this piece is really well organized. It starts by listing my reason for writing, followed by relative qualifications and closing statements”.

A total of 47% of the students (n = 22) mentioned that ChatGPT generates high-quality sentences, specifically in the following aspects: professional or formal word choices or expressions, eloquence of writing, correct grammar, clarity of meaning, advanced sentence structures, and smooth transition at the sentence level. Using professional or formal words and expressions is the most frequently mentioned aspect. For example, S12 wrote, “I think some of the language that ChatGPT used sounds more professional than what I would say naturally, such as more formal words that I would have to search a thesaurus for”. S4 wrote, “It used more professional vocabulary. It also had no grammatical errors”, which included the aspects of professionalism and grammar. S21 commented on the improvement of sentence structure by ChatGPT: “The AI also combined some of my sentences so I did not repeatedly start sentences with ‘I’, which made it better”.

Some students also mentioned other advantages of ChatGPT, including idea generation, concise contents, and extracting essential information. In total, 34% of students (n = 16) commented on idea generation, particularly in (1) generating alternative ideas that were not thought of by the student but were helpful for the writing or (2) deducing new information based on provided information. For example, S13 wrote, “I like how ChatGPT added some googled information about highlights of the company itself and added one generated paragraph about what specifically excites me and caters my interest in the company even though I didn’t include anything about this in the prompt. I noticed I didn’t really emphasize this in my cover letter so I made sure to go back and add an additional sentence about what caters my interest in my introduction paragraph”.

Overall, 30% of students (n = 14) commented on ChatGPT being good at keeping contents concise. S2 wrote, “The condensing aspect of the AI-generated piece was admittedly better than what I could have written. I sometimes struggle with including too much content and it’s often difficult to choose what to cut down on”. A total of 21% of students (n = 10) thought that ChatGPT was good at extracting essential information. For example, S10 wrote, “It was able to speak to a lot of points that I was trying to portray in my own version of my cover letter”.

3.3. Weaknesses of ChatGPT

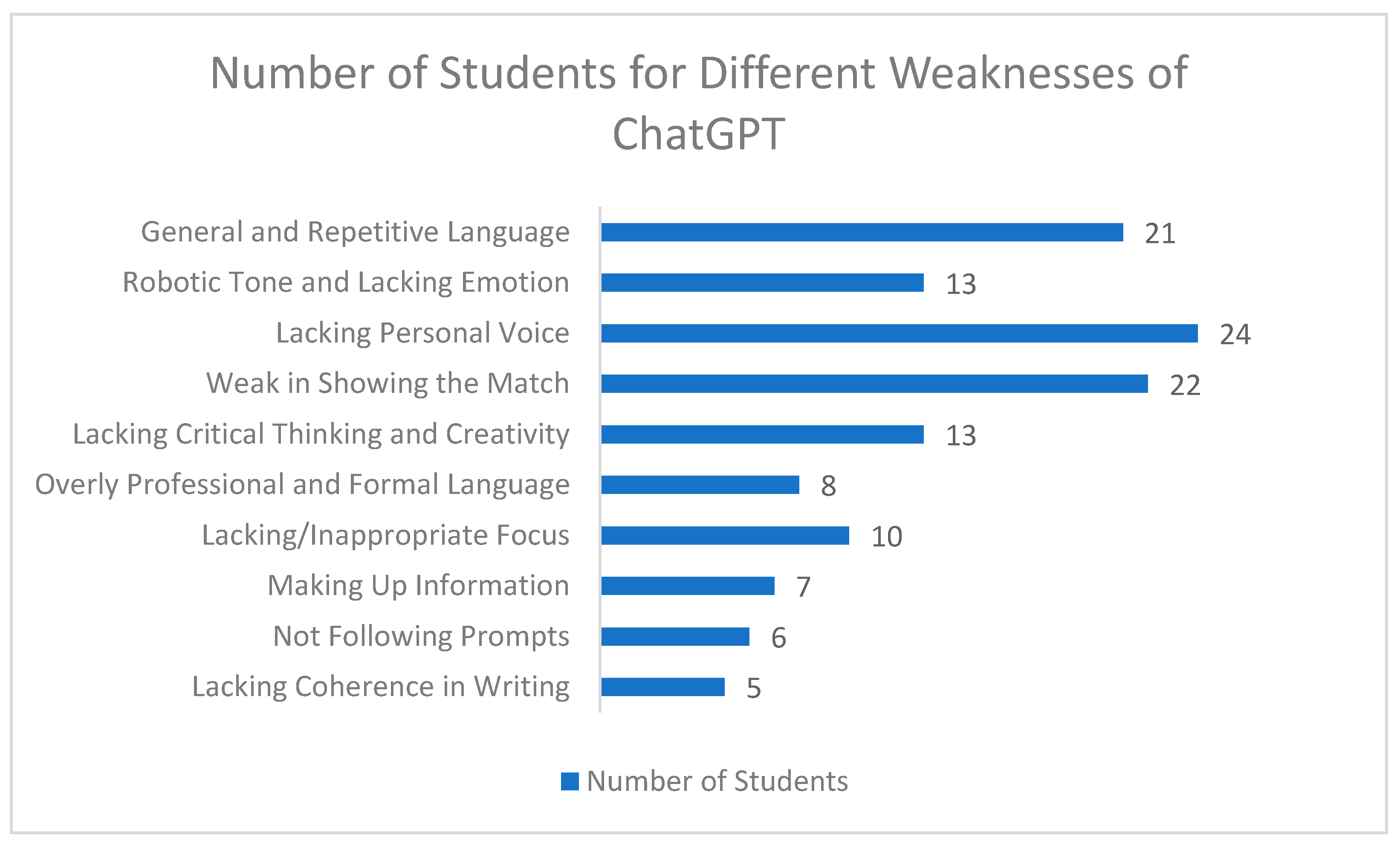

Figure 5 shows the coding results of Q3: students’ views of the weaknesses of using ChatGPT for writing the application letter. About 45% of students (n = 21) pointed out that the language generated by ChatGPT is too general or repetitive. For example, S12 wrote, “I also think the AI letter was repeating itself but with different words”. And S16 wrote, “The AI version included some phrases that were too wordy and generic”. A total of 28% of students (n = 13) complained about the robotic tone and the lack of emotion in the language generated by ChatGPT. For example, S9 wrote, “It doesn’t resemble how a human would speak or try to convey their thoughts”. S19 provided a more detailed description of this issue, “AI is too impersonal with a lacking voice and personality to it. The sentences are very bare in terms of sounding generic and like any other person. There is no ‘me’ in what it describes”.

A total of 51% of students (n = 24) also critiqued that the AI-generated letter lacks a personal voice. Although the majority of students acknowledged the personal touches as one of AI’s strengths, the personal touches are usually limited to a superficial level of incorporating personal experiences listed on the resume. This type of simple list of experiences is not enough to provide a personal voice for the letter. In addition to S19’s response as an example of lacking personal voices (and robotic tone), S5 also wrote, “I also don’t feel like my personal voice was there to reflect how I would uniquely write. Although it was able to synthesize the information it had about me to add extra verbiage, I felt like my personality was not truly conveyed”. And S15 expressed in a more concise way, stating “there are no personal touches to the writing as it only has and uses the information it is given”.

Overall, 47% of students (n = 22) commented that the writing generated by ChatGPT is weak in showing how the candidate matches the position. S13 provided a brief but representative example response: “I feel it didn’t do a good job at shaping my personal experiences towards the importance of the job role”. S3 provided a more detailed and specific example response: “In general, I feel that the piece mentioned too many of Disney’s values that it was hard to establish a theme for my candidacy. What I mean by this is that if this cover letter were to be shown to a hiring manager, it would be hard for me to stand out”.

A total of 28% of students (n = 13) wrote about the lack of critical thinking and creativity in AI-generated letters. Lacking critical thinking and creativity includes situations when the student explicitly wrote the writing is not “interesting” or lacks “novelty”, the writing follows a formulaic style of writing, and the writing just lists the information or experiences from the resume without further elaboration. For example, S1 wrote that “it would have been better to start with something that is more interesting for the reader”. S5 wrote, “The output read fairly formulaic. The organization was clear but lacked anything novel…”.

In total, 17% of students (n = 8) believed that ChatGPT uses overly professional and formal language. For example, S4 wrote that ChatGPT “used exaggerated vocabulary that I wouldn’t normally use in everyday communication”. S2 wrote, “ChatGPT would give responses with words that were fancier than necessary, giving my cover letter an overall uptight, too professional feel”.

A total of 21% of students (n = 10) complained that ChatGPT lacks focus or has inappropriate focus in the writing. An example of lacking focus is by S7, who wrote that ChatGPT “went over my academic achievements too much; Did not mention anything specific about the company of the culture”. S6 provided an example response of inappropriate focus, “In my own piece, I went into depth discussing why I want to advocate for the elderly through a career in law, as well as my experience with my grandfather which led me to this decision; however, the AI-generated piece skimmed over this major aspect of my journey to decide to go to law school and didn’t highlight its importance and significance”.

Moreover, 11% to 15% of students (n = 5~7) also mentioned some other weaknesses, such as lacking connection between pieces of information to make the writing a cohesive piece, making up information, and not following prompts or instructions.

3.4. Improving the Use of ChatGPT

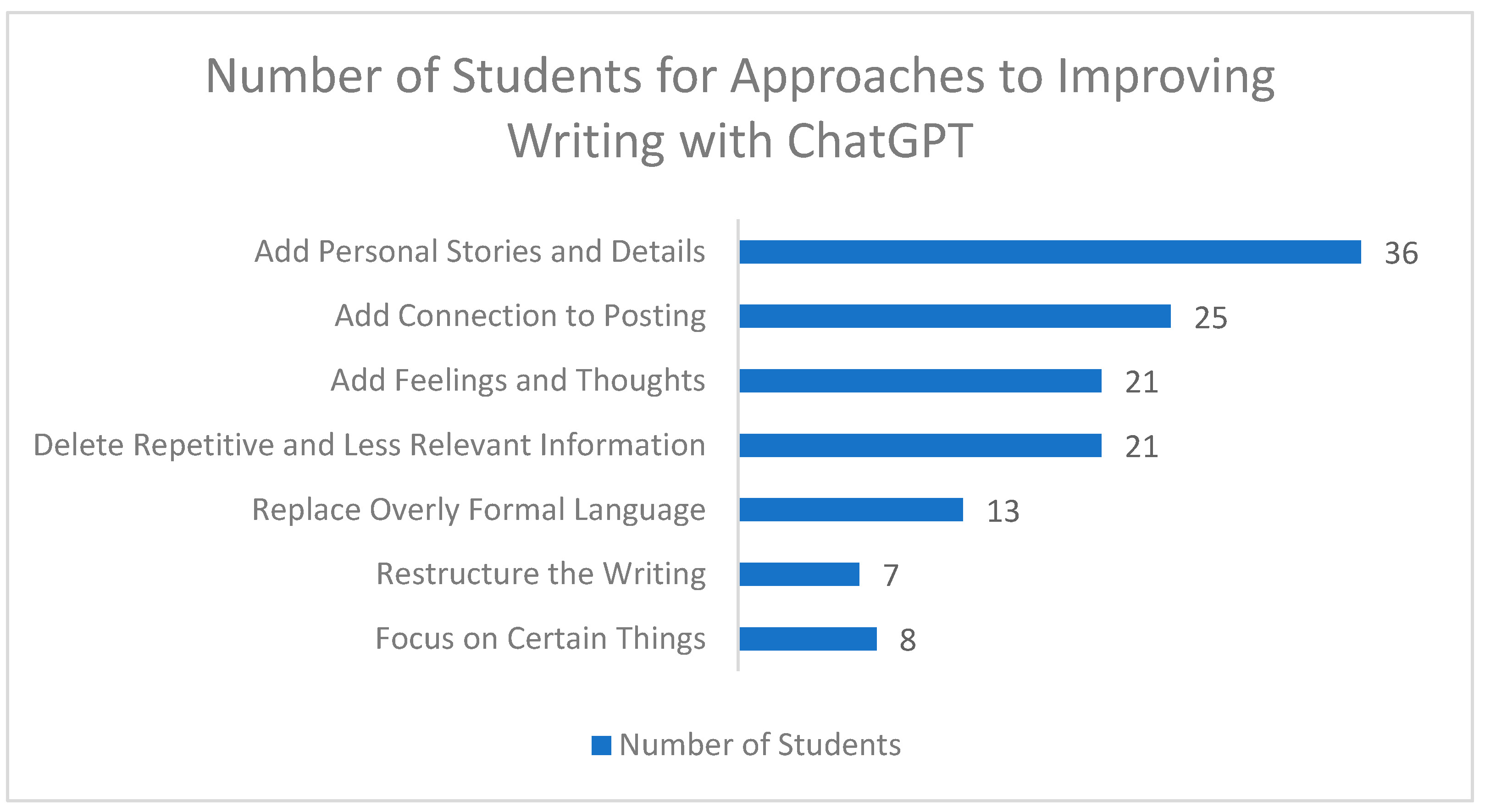

Students’ responses to Q4—what they wanted/needed to revise to improve the AI-generated writing—highly matched their views of the weaknesses of ChatGPT.

Figure 6 shows the distribution of students over the different approaches for the improvement. Aligned with a major critique on lacking personal voices, most students (77%, n = 36) believe that it is necessary to add personal stories or details to support better storytelling, such as the details behind the experiences listed on resumes and the stories of how students were motivated to pursue a career relevant to their application. For example, S8 wrote, “I would feed it information about myself and continue prompting it to cater its responses directly to my experiences and why I want to be in medicine”. And S7 wrote, “Add more personal anecdotes to support skills that it mentions”.

A total of 53% of students (n = 25) mentioned adding connections to the job posting in the letter, which aligns with the comment that ChatGPT is weak in showing the match between the applicant and the position/program. Students want more explicit words in the letter to show how their skills or experiences match the job/program. An example response of this was provided by S14: “I would alter it with more tailored explanations related to the job postings, such as activities I did during my internship and specific course material/tools I used during my tutoring session”.

To address the issue of robotic tone and lacking emotion, 45% of students (n = 21) brought up adding personal feelings, emotions, or thoughts to the writing. Example responses include but are not limited to the following: (1) “I would talk about how I felt and what I learned through these experiences that shaped me into the person I am today” (S1); (2) “I could become the author through revision if I contributed the feelings and thoughts I had throughout the experience into the paper to make it more humanistic. I think the paper just needs to have more emotion to it because it didn’t execute my experiences to their maximum potential” (S9).

Moreover, 45% of students (n = 21) also thought of deleting repetitive, made-up, or less relevant information or language. For example, S12 wrote, “I would also have to cut out and/or rearrange some sections to make it more concise and flow better”. S18 wrote, “As mentioned before, there are parts that I wouldn’t add, such as my awards as they are not relevant to the job description”.

A total of 28% of students (n = 13) planned to replace the overly formal, professional, or unfamiliar language with more personal and natural language that matches their own writing style. For example, S13 wrote, I would also have to make a lot of changes in word choice to make me not sound like a robot”. And S7 wrote, “Change greeting and sign off to things I would actually say. Change words that I realistically would never use to more approachable phrasing”.

As most students were happy with the writing template generated by ChatGPT, fewer students mentioned restructuring the writing. A total of 15% of students (n = 7) wrote about restructuring or reorganizing the information (e.g., changing the sequence of sections or paragraphs) and changing the format of writing (e.g., changing it from letter format to essay format). Echoing some students’ complaints about lacking or inappropriate focus, 17% of students (n = 8) decided to change the writing from listing many things or experiences from the resume to focusing on things that are most important for the application.

Apart from the specific revision ideas, 6% of students (S5, S15, and S31) responded with their higher-level thinking about how to better use ChatGPT for writing. S5 elaborated on how to write with ChatGPT through revision at a higher level: “In fact, the answer to the previous two questions would be a great workflow to be an author through revision. Answering those two questions inspired further prompting to influence the quality of the output. By critically and iteratively assessing the quality of the prompt and articulating the pros and cons of a response we can be an author through revision. Each “con” can inform a future prompt that hopefully makes the response better; through this we can achieve a response of appropriate quality. We can consider developing a procedure to achieve iteratively better response considering how the AI works and how it learns and stores information”.

S15 also summarized his/her views of how to have ChatGPT generate better writing: “As the AI bot simply uses the information it’s given by you, if you add more instructions that are specific to points you want to get across, tone of writing, or anecdotes then the piece could become more personalized. The AI bot can definitely act as an idea bank where good points or phrasings could act as inspiration; however, taking the piece as a whole would feel more impersonal”. S31 wrote, “To become the author through revision and enhance the AI-generated response, I’d focus on personalization, adding a human touch, storytelling, clarity, alignment with the position, and proofreading”.

There are also voices against the use of AI to assist writing. For example, S46 wrote, “Despite undergoing many iterations of prompt construction and using the most powerful engine available to me, I would rather write from scratch than revise the AI-generated cover letter”.

3.5. Overall Attitude

The distribution of sentiment analysis results for Q5 is shown in

Figure 7. Except for one slightly negative result (−0.05 for the response by S41), all the remaining responses were rated as positive. S41’s response was “I learned that AI is a useful tool to get started on writing something because it helps a lot with formatting, however, it is almost useless in writing something that is meant to be personal and tailored to a specific person/program”.

The other responses were similar to S41, in the way of mentioning both strengths and weaknesses of AI tools for writing. However, most of them did not use as strong a word as “useless”. For example, S10 wrote, “AI is a good starting point to get ideas of structure and word choice, but ultimately lacks the aspect of personalization necessary when writing about your own experience. To create the best response, you have to have somewhat of an idea of what you want to include or write about”. The polarity of this response was rated as 0.38.

S35’s response was rated as 0.8, which was the only one far beyond the rest. The response was “I learned that Chatgpt can provide a great structure for some papers including cover letters. A great jumping off point”. It only included positive comments, which was probably the reason for its high polarity result.

From the sentiment analysis results, we can tell that the 47 students generally had a positive attitude toward AI/ChatGPT after they personally tried out writing with the tool, though they were also aware of the limitations of AI/ChatGPT.

4. Discussion

Based on our findings, students generally acknowledged that Generative AI tools can be helpful in some respects for their writing. They shared their perceptions of both the strengths and weaknesses of using AI tools to complete this writing task, either a job application letter or a personal statement. From their personal trials with the tools, they learned how to prompt the AI tool to generate better writing products. It is also interesting to note that ChatGPT has been found to be a well-recognized Generative AI tool in our study and almost all existing studies.

Comparing the results in our study and existing studies, some of our findings regarding students’ perceptions of using ChatGPT for this specific writing assignment are consistent with students’, educators’, or researchers’ views of using ChatGPT for learning in general. Our finding of students’ overall positive attitude toward ChatGPT is aligned with the prior study [

20] on students’ perceptions, in which the author found that students generally acknowledged in the survey and interview that ChatGPT was helpful and useful for their learning. Students’ positive attitude seems to conflict with the concerning attitude held by many educators and researchers [

9,

10,

15]. Regarding the strengths, students in our study identified the strengths of ChatGPT in always generating good writing templates, which occurred as generally good quality in [

21]. Regarding the weaknesses, students in [

22] also pointed out in interviews that ChatGPT was limited in contextual accuracy and personal writing style, which are like “lacking personal voice” in our findings. The weakness of being too general and repetitive in our findings was also summarized by Kohnke and colleagues [

16]. Apart from these shared findings, our study showed more concrete views of students based on their hands-on writing experience with the AI tool.

4.1. AI Ethical Concerns in Writing Education

Our findings can help relieve some concerns about cheating in writing [

31,

32]. In their responses, students are not overly optimistic about using Generative AI tools to replace their own writing. They believe that the AI tool is good at generating a template with good structure and professional language for them to start with, but they are also aware that the AI-generated pieces did not meet the expectations of good application letters or personal statements because of the generic and vague contents. Our evidence indicates that students in our study were able to determine that AI-generated writing was insufficient; their use of the tools, moreover, enabled them to also find the limits of Generative AI tools. These two findings suggest that while cheating using AI is a valid concern, such concerns may be mitigated by creating a learning environment that

encourages the use of AI—when students were allowed to use Generative AI, they found its limits.

4.2. Strategies to Regulate the Use of AI

Educators should strategically regulate students’ use of AI tools [

33]. First, personalizing the writing tasks for students can be a strategy to prevent cheating. As shared in students’ responses, AI tools can hardly provide personalization for their writing of applications or personal statements. To reach a satisfactory level of personalization, they have to provide AI tools with enough details of personal stories and their emotions and thoughts from their personal journey, which is almost like writing a full draft by themselves. Therefore, it is worthwhile for educators and researchers to explore some other personalized writing tasks that can effectively prevent students’ cheating with Generative AI tools.

Next, it is important for educators to set appropriate rubrics for the evaluation of students’ writing. The qualities of writing that are emphasized by the instructor can largely determine the qualities of writing sought by students. If the standard for a good cover letter or personal statement goes beyond the level of work generated by AI tools, students will know that AI cannot easily replace their own writing and, hence, need to put adequate effort into their writing for a satisfactory grade. Thus, we suggest that universities and schools should offer regular training courses to update educators about the capabilities of AI tools so that they know what appropriate rubrics should be like and can adjust promptly.

Moreover, educators need to provide guidance to students on how to use AI tools to support their improvement in writing. From students’ responses, we know that prompting is an important skill for students to write with AI tools, which is aligned with the rising recognition of prompt engineering [

34]. In this study, students received little instruction about how to use ChatGPT or other AI tools, so they experimented with different versions of prompts, learned, and improved during the iterative process. To support students’ learning with AI tools, educational systems should incorporate training on the use of AI tools to students, including training on how to prompt AI tools to receive satisfactory results. We also call for more research on developing effective training courses on AI tools.

4.3. Limitations

This study has its limitations. The first limitation exists in the pre-experimental research design with a single group and only post-assessment. This design allows us to understand students’ perceptions of using Generative AI tools for writing after the completion of the task. Yet, it does not provide the opportunity to examine the change in students’ perceptions and the influential factors behind it, which can be a promising direction for future research with (quasi-) experimental design and statistical methods. Second, the convenience sampling limits the generalizability of the study. The student participants were recruited from a single university, and they cannot represent all college students since the student population in each higher-education institution may vary depending on its country, location, culture, etc. It will be interesting for future research to investigate if the study will yield similar results when replicating it at different universities.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to fill in the gap of empirical research on students’ perceptions of using Generative AI tools for writing. In our study, the instructor of an advanced writing course designed an assignment, in which students were directed to draft a job application letter or personal statement for graduate school. After completion of the assignment, 47 students responded to an open-ended survey that asked about their writing process, what worked, what did not work, how to better write with AI, and the general lessons learned. We analyzed students’ responses with thematic analysis and sentiment analysis methods. Our findings show that (1) students went through multiple rounds of prompting and they prompted AI tools to include resume information, job description, article length, and highlights; (2) students identified strengths of AI, which included personal touches, connection to the topic, template generation, sentence quality, and idea generation; (3) the weaknesses of AI included general and/or repetitive language, robotic tone and lacking emotion, lacking a personal voice, and lacking critical thinking and creativity; (4) students wished to improve AI-generated writing by adding personal stories, connections to posting, feelings and thoughts, and deleting repetitive language; and (5) their overall attitudes toward AI tools were positive. We believe our findings can help relieve some concerns about cheating in writing. We also suggested strategies to regulate the use of AI, including personalizing writing tasks, setting appropriate evaluation rubrics, and providing guidance to students on the use of AI for learning. This study contributes to our overall understanding of how college students use Generative AI technologies when they are encouraged to do so, which sheds light on the integration of AI in educational settings.