1. Introduction

Wh-questions are an important research domain as they are fundamental to children’s developing grammar [

1]. As the generation of

wh-questions involves certain derivational steps, the productive use of this structure could be a sign of syntactic establishment in early childhood language acquisition. Furthermore,

wh-question acquisition also facilitates verbal reasoning capacities in young children [

2], and lays the foundations for children in their early years to engage and have meaningful interactions with their surroundings.

The development of

wh-questions in bilingual mode seems to have aroused attention and interest over the past three decades [

3]. This is because monolinguals only process one language in their minds, whereas bilinguals juggle two [

4,

5]. Whether one language could influence the other or vice versa is an interesting topic that would be worthwhile to explore.

BFLA studies focus on children who acquire both languages from birth. Most such studies indicate that bilingual children’s language acquisition proceeds like that of their monolingual peers in each of the two languages [

6,

7]. For ESLA children, the age of exposure to L2 typically starts after moving to the L2 speaking country [

8,

9,

10]. Li Wei’s (2011) [

8] and Hakuta’s (1976) [

9] studies show a large proportion of transfer. Our next inquiry is what ESLA children’s bilingual developmental pathway looks like if they are exposed to L2 before migration and whether qualitative differences exist between BFLA and ESLA children.

Currently, around 10.7 million Chinese live overseas [

11], and the number is still increasing. Unlike previous studies, which focus on children who started receiving L2 exposure after arriving in the host country, an increasing number of young children start to receive L2 English input in China to better adapt to and integrate into the host country. Previous studies show that the development of bilingual

wh-questions in Mandarin-English BFLA children appears to proceed in a language-specific way, without noticeable cross-linguistic interaction [

3]. So, are these migrant children fundamentally different from their BFLA peers in terms of

wh-questions? Does their L1 continue to develop in the L2 environment? Is there any cross-linguistic interaction between their L1 and L2? These questions have been rarely broached to date.

In order to answer these questions, we selected the target Mandarin-English bilingual child (codenamed GG) (aged between 3;04 and 5;05), as she represents the growing migration trend. Additionally, the child moved to Australia at age 3;07, a widely-held demarcation line between BFLA and ESLA [

12]. Thus, it is theoretically significant to investigate whether her bilingual developmental pathway resembles that of a BFLA or ESLA child. Furthermore, interconnected with migration is the change of environmental language (Lε) [

3], and upon the change of Lε, parental input could also be changed due to school enrollment. As such, it is meaningful to look at the interconnections among age, input, and Lε.

2. Literature Review

The section presents the related literature regarding the bilingual acquisition of wh-questions in a plethora of language combinations. This is to identify research gaps and scaffold research questions afterwards.

One of the systematic Cantonese-English bilingual studies was conducted by Kwan-Terry [

13]. The longitudinal study, based in Singapore, focused on a BFLA child from age 3;06 to 5;00. The research findings show that the BFLA child’s Chinese (Cantonese) acquisition was similar to monolingual peers, with

wh-words placed in situ from the very beginning of the study. However, the development of the English

wh-questions resembled neither L1 nor L2, but somewhere between L1 and L2. In other words, the child’s English questions showed certain features of both Chinese and English. From age 3;06 onwards, not all of the child’s English

wh-questions exhibited a

wh-fronting pattern, which could be due to the shared word order SVO in Chinese and English and the influence from the dominant language (Chinese). The child’s fully productive use of

wh-fronting English questions was recorded at 4;03. Interestingly, while the child’s English question pattern was established, his Chinese

wh-questions started to show signs of the English pattern. The study has proposed that language dominance plays an important role in shaping the child’s bilingual

wh-questions. This is further borne out by Yip and Matthew [

1].

Another systematic academic inquiry in Cantonese-English bilingualism was carried out by Yip and Matthew [

1]. In their ground-breaking longitudinal work, Yip and Matthews investigated six BFLA Cantonese-English bilingual children between the ages of 2;01 and 3;06 in Hong Kong. The study shows that these children’s L1 Cantonese

wh-questions resembled those of their monolingual peers, but their L2 English

wh-questions exhibited qualitative differences from their monolingual English peers. The high rate of

wh-in-situ questions in English is deviant from the monolingual developmental trajectory. One child, named Timmy, even displayed a significantly high proportion of 65% of

wh-in situ questions from age 2;01 to 2;11. The developmental pathway of these children’s English questions systems could be summarised as a three-stage model: stage 1

wh-in-situ, stage 2

wh-in-situ and

wh-fronting and stage 3

wh-fronting. This is similar to Kwan-Terry’s [

13] study. In other words, both studies show a transitional stage, in which the ungrammatical

wh-in-situ and the grammatical

wh-fronting structures co-exist. With respect to the transfer, language dominance could work in tandem with structural overlap [

14] (Cantonese and English echo questions share the same word order) in justifying the presence of the language interaction. However, other studies have found that language dominance and overlapping structures may not trigger the emergence of a transfer.

In their cross-sectional study, Strik and Pérez-Leroux [

15] focused on the acquisition of French questions in fifteen Dutch-French bilinguals between the ages of 4;06 and 8;08 in France, where French is the predominantly used language. Two children’s parents were Dutch, and these families adopted the context-bound “one language, one environment” policy [

16]. Another ten out of the fifteen children were born in the Netherlands and moved to France between the ages of two and four. Data indicate that these children produced

wh-fronted questions without subject-auxiliary inversion, which was similar to their French monolingual peers. Strik and Pérez-Leroux further justified this developmental pattern by citing the children’s early introduction to French. This does not lend support to the hypothesis of language dominance [

1] and structural overlap [

14]. In other words, dominance in the Dutch language did not contribute to the emergence of the targeted deviant structures in French, except for the developmental stage of the absence of subject-auxiliary inversion (SAI) [

17] in French questions. Dutch requires obligatory

wh-fronting, whereas French allows both

wh-fronting and

wh-in-situ, which suggests that structural overlap does not trigger transfer. However, the absence of SAI in both monolingual and bilingual production suggests that derivational complexity [

15] may play a major role in preventing a transfer from emerging: the complex structure, which is higher in derivational rank, cannot be projected onto the simpler structure in another language.

Strik and Pérez-Leroux [

15] furthers our understanding regarding the mechanism of cross-linguistic interaction. However, this theory seems not to be applicable in other studies. Mishina-Mori [

18] longitudinally examined two Japanese-English BFLA children aged between 1;11 and 3;03 in the United States. Unlike Strik and Pérez-Leroux [

15], these families adopted a “one parent, one language” (OPOL) policy. One child, named Ken, received more exposure to English than Japanese, whereas the other child Rie, had more input in Japanese than English. Data indicate that the two bilinguals basically observed the respective

wh-movement rules in both Japanese (

wh-in-situ) and English (

wh-fronting). Quite obviously, this study meets the condition for transfer, but no transfer materialised. Japanese’s

wh-in-situ structure demands less cognitive processing, thus it is derivationally simpler than English

wh-fronting, in which several steps are involved in the transformation process. The lack of cross-linguistic interaction could be justified by isomorphism proposed by Yip and Matthews [

19], who hold the view that the same word order could potentially exert a facilitating role in transfer emergence. In other words, Japanese’s SOV differs from English’s SVO, thus the syntactic incompatibility could effectively block the transfer. This proposal is supported by a study conducted by Park-Johnson [

20].

Park-Johnson [

20] examined seven ESLA Korean-English bilinguals aged between 2;04 and 7;11 in the United States. The input pattern was context-bound “one language one environment” [

16], in which Korean was used at home and English was spoken in extra-domestic settings [

3]. Data show that these bilinguals acquired Korean and English

wh-questions in a language-specific manner, despite certain differences in terms of the developmental rate in their weaker language (English). In other words, no cross-linguistic interaction was detected. Korean is derivationally simpler than English. However, the Korean

wh-in situ pattern was not projected onto English. Why? Yip and Matthews [

19] claimed that isomorphism could be the fundamental factor in the non-transfer. As an SVO language, English differs from Korean’s SOV, thus preventing the transfer. However, isomorphism is language internal factor; language external factors should also be taken into account.

In their pioneer longitudinal work by Qi and Di Biase [

3], a BFLA Mandarin-English bilingual child in Australia aged between 1;07 and 4;06 was investigated. Data show that no transfer was found between the two languages, despite certain developmental features in his English

wh-question profile, such as the absence of subject-auxiliary inversion (SAI). The child’s Mandarin consistently displayed the

wh-in-situ pattern, while his English invariably exhibited

wh-fronting. This study meets all the conditions for cross-linguistic interaction proposed by the previous studies: Mandarin dominance, Mandarin’s overlap with English, Mandarin’s simpler derivation and Mandarin’s isomorphism with English. Nevertheless, transfer was not found. The researchers have advanced the transfer theory by proposing that the environmental language (Lε) has an influence on bilingual language acquisition. Lε is defined as the predominant extra-domestic language [

3]. It is corroborated that if the weaker language (here referring to English) coincides with the Lε (here referring to English), then the former could gain strength from the latter, keeping the balance of dominance in a reasonable manner and thus keeping the bilingual development separate.

Riham [

21] investigated the production of Egyptian Arabic

wh-questions in 16 Arabic-English bilingual children in the UK or Canada (age range 5;06–12;06, mean age: 8;11), with 18 monolingual Arabic-speaking children in Egypt as a control group. Results show that these bilingual children exhibited significantly higher rates of

wh-fronting in their Arabic, suggesting a cross-linguistic influence from English. This study contributed to our understanding regarding the mechanisms of structural overlap in the emergence of transfer. However, what the developmental pathway looks like over the process of migration, whether the changed Lε could play a role, and whether the later age of exposure to L2 could influence ESLA children’s language acquisition have not been broached.

The present study is different from the above literature in the following aspects. First, the age range of the bilingual child in this study is 3;04 to 5;05, a critical age [

12,

22]. Second, the child had limited L2 English input before migrating to Australia, whereas nearly all of the children in the reviewed studies received no prior L2 input. Third, the child’s parental input fluctuated in the process of migration, while previous research focused on stable parental input. Fourth, the child experienced a changed Lε (from Mandarin to English), rather than developing in the same Lε.

Research Questions:

RQ 1. Does the Mandarin-English bilingual child GG show similar developmental patterns of Mandarin wh-questions in comparison to BFLA children?

RQ 2. Does the Mandarin-English bilingual child GG show similar developmental patterns of English wh-questions in comparison to BFLA children?

RQ 3. Does the changed environmental language (Lε) influence the child’s bilingual wh-questions development?

3. Overview of Mandarin and English Wh-Questions

Mandarin and English are typologically distant language constellations [

23,

24,

25]. This is especially outstanding in the domain of

wh-questions. The formation of Mandarin

wh-questions simply involves the replacement of the questioned constituent with the corresponding

wh-words in the original place, thus, Mandarin is a

wh-in-situ language. In other words, Mandarin involves no overtly derivational transformation. An example is presented to illustrate this:

ni3men zuo4 shen2me? [

26]

you 2PL do what

(What are you doing?)

The configuration of the above Mandarin wh-question involves the replacement of questioned constituent with the question word (shenme/what), thus no overt derivation is required.

In order to generate English wh-questions, multiple steps are involved. Specifically, the wh-element is required to displace to the clause initial position and the application of SAI is also compulsory except under certain syntactic conditions. The following example shows the feature.

This example is constructed upon the questioned part (something) in the pre-transformed declarative: ‘I buy something’. After placing the wh-word in the clause’s initial position and applying SAI, the wh-fronting structure is generated.

One exception for the English wh-in-situ question is the echo question, which shares the same wh-words position with Mandarin Chinese.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. The Approach of Case Study

As a time-honoured approach [

23,

24], the longitudinal case study has its advantages. An in-depth investigation with adequate data [

27] over a certain period of time can capture a holistic picture for specific inquiries [

28].

As a parent researcher, the first author of the study has the privilege to ethically approach the target child, a common practice in bilingualism studies over the past century [

1,

3,

23,

24,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42].

4.2. The Informant

The target bilingual child in this study is codenamed as GG. She was born in China and moved with her Mandarin-speaking parents to Sydney, Australia at age 3;07.

GG’s bilingual development was divided into three stages: stage 1 in China (birth-3;06), stage 2 in Australia without preschool (3;07–4;10), and stage 3 in Australia after attending preschool (4;11–5;05).

During stage 1, the child GG received L1 Mandarin input since birth. At age 1;02, the child started to receive L1 Mandarin input for 5 h and L2 English exposure for 0.5 h per day in China. At the beginning of stage 2, the child moved with her parents to Sydney, Australia. However, the child did not attend preschool immediately after moving. During this stage, GG’s L1 Mandarin input was reduced to 4.5 h and L2 English increased to 2.5 h per day. In stage 3, the child GG attended preschool. At this stage, GG’s L1 Mandarin input was significantly reduced to 2 h and L2 English dramatically increased to 6.85 h per day.

GG’s parents adopted a context-bound “one language one environment” family language policy proposed by Qi, Di Biase & Campbell [

16]. The choice of language hinged on the context: Mandarin at home and English for bedtime stories and extra-domestic settings.

GG’s main interlocutor was her father, who was a university lecturer in Teaching English to Speakers of Other languages (TESOL). Her father was fluent in both L1 Mandarin and L2 English, with an intermediate level of L3 French and beginner level of L4 German, and addressed the child in Mandarin for most of the daily routines and English during bedtime stories and outside the home setting. GG’s mother only addressed the child in Mandarin regardless of at home or extra-domestic settings, in China or in Australia.

4.3. Dataset Description

The dataset contains two major types of data: (1) audio recordings and (2) diary entries. The method we follow here is to collect natural linguistic data as primary data by making audio recordings at regular intervals over time, supplemented by diary entries and three video recordings (birthdays).

The dataset consists of 89 recordings totalling 2632 min, starting from age 3;04 (year; month) and continuing to age 5;05. The first five recordings were obtained in Xi’an in Northwest China’s Shaanxi Province to establish the research baseline, from which the researcher can trace her bilingual development path over time. All the other recordings were taken in Sydney, Australia. The recordings lasted about 29.57 min on average, with the first five China-based mixed recordings averaging 47 min. It is essential to point out that the child was verbally expressive. Therefore, her speech data were abundant.

4.4. Data Treatment

In order to accurately calculate the child’s Mandarin wh-questions, the following structures were discarded: single wh-elements, echo questions, subject shei (who)-questions, subject shenme (what)-questions, and subject nayige (which)-questions, as the positions of these Mandarin wh-words and their English counterparts are the same in-situ. Incorporating these structures would inflate the results and thus weaken validity. Another structure, Mandarin wheishenme (why)-questions were also screened out as both wh-in-situ and wh-fronting are acceptable. Thirdly, Mandarin topicalisation was also exempted from calculation, as this structure is typically placed at the clause initial position. If a wh-question is a topicalisation, then it will be disguised as wh-fronting. Finally, no action was taken on Mandarin null subjects, as this would leave wh-words automatically fronted, causing difficulty in determining whether they are indeed fronted wh-questions

The data treatment for English wh-questions was straightforward, as English is a non-null subject language without topicalisation. Thus, only single English wh-words and echo questions were excluded.

4.5. Data Analysis

All of GG’s data were manually transcribed according to the criteria designated by CLAN (Computerised Language ANalysis) [

43]. This study utilises the CLAN software (V02-Sep-2018) to analyse the bilingual data. The most used programs are FREQ (count the frequencies of certain types and tokens) and COMBO (to extract the whole string of the required linguistic unit) to derive the rate of bilingual

wh-questions and syntactic structures via context concurrence.

4.6. Comparison with Monolingual Data

The study also retrieved data from the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES) [

43] to make comparisons between the ESLA child GG and her monolingual Mandarin and English peers. After setting the required age range (3;04–5;05) and languages (Mandarin and English), we derived a monolingual Mandarin child named Xue’er (aged 3;04;01–5;05;01) and a monolingual English child named Adam (aged 3;04;18–5;02;12). Xue’er’s data are from

https://sla.talkbank.org/TBB/childes/Chinese/Mandarin/Zhou3 (accessed on 1 August 2021) and Adam’s are available at

https://sla.talkbank.org/TBB/childes/Eng-NA/Brown/Adam (accessed on 1 August 2021).

5. Results

5.1. The Development of GG’s Mandarin Wh-Questions

Table 1 presents GG’s emergence order of Mandarin

wh-questions.

GG’s emergence order of Mandarin wh-questions is summarised as follows: the earliest emergence was shenme (what) questions at age 1;05;23, closely followed by nail (where)-questions at 1;06;15. Then, five months later, at 1;11;19, shei (who)-questions emerged, closely followed by zenmeyang (how)-questions at 2;00;04 and nayige (which)-questions at 2;01;16. Twelve months later, shenmeshihou (when)-questions appeared.

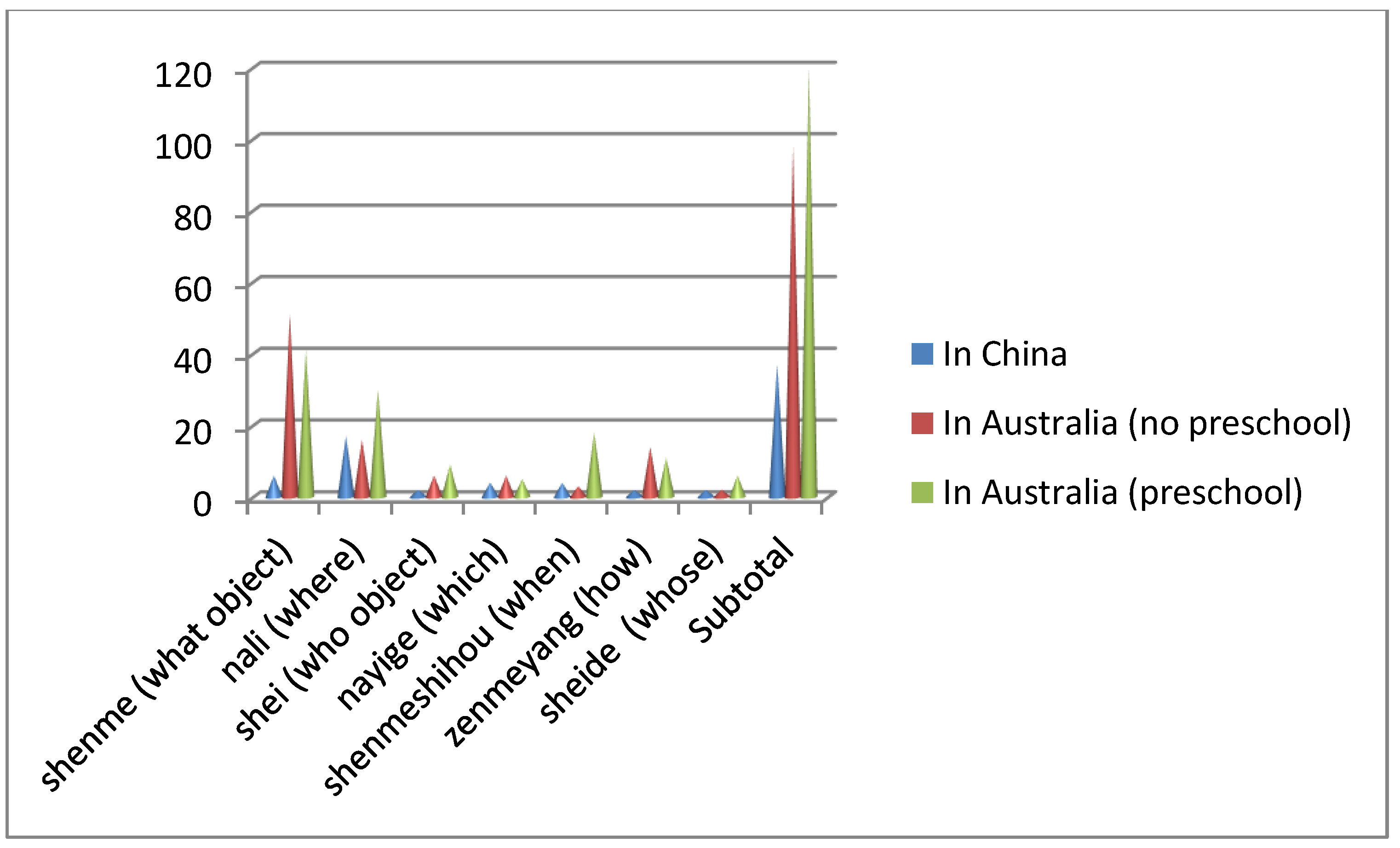

Table 2 and

Figure 1 show that a total of 225 Mandarin

wh-questions were produced by GG between the ages of 3;04 and 5;05. Among those, 238 were in-situ questions, taking up 94% of the child’s total

wh-question output; 17 were

wh-fronted questions, accounting for 6%. This finding is qualitatively similar to Qi and Di Biase [

3], where they reported a percentage of 100% of in-situ Mandarin questions from the BFLA child James.

The dataset is further divided into three stages: Stage 1 (in China); Stage 2 (in Australia without attending preschool) and Stage 3 (in Australia after attending preschool).

During stage 1, when GG was in China, she produced 37 Mandarin wh-questions: 6 shenme (what)-questions, 17 nali (where)-questions and 2 sheide (whose)-questions, and all of those structures were wh-in situ.

Stage 1 data show that the child’s Mandarin questions mainly distributed between

shenme (

what) and

nail (

where). This is comparable to her Mandarin monolingual peers [

44] and English monolingual peers [

45]. The common feature of the early emergence of “what” and “where” questions in other languages may reflect the shared cognition of human beings: to name an object and followed by position. The following example is presented:

At the beginning of stage 2, GG moved to Australia at age 3;07;02. The location and the environmental language change is the defining characteristic of this stage (3;07–4;10). At this stage, GG stayed with her Mandarin-speaking parents most of the time, without attending preschool. She produced a total of 98 Mandarin wh-questions, all of which were in-situ. Shenme (what)-questions (51 tokens), nail (where)-questions (16 tokens) and zenmeyang (how)-questions (14 tokens) ranked top three among the most frequently produced, followed by shei (who object)-questions (6 tokens), nayige (which object)-questions (6 tokens), shenmeshihou (when)-questions (3 tokens) and sheide (whose)-questions (2 tokens). This stage witnessed the blossoming of GG’s Mandarin wh-questions, as both the types and tokens increased significantly. The following example shows the increasing complexity of her Mandarin wh-questions.

ni3 zhi1dao4 ta1 hou4mian shi4 yi1ge4 shen2mema1? (4;04;13)

you 2SG know he behind is one CL what

(Do you know what it is behind him?)

During stage 3 (4;11–5;05), the bilingual child GG produced 120 Mandarin wh-questions. The most frequently produced were shenme (what)-questions (41 tokens) and nail (where)-questions (30 tokens), followed by shenmeshihou (when)-questions (18 tokens), zenmeyang (how)-questions (11 tokens), shei (who object)-questions (9 tokens), sheide (whose)-questions (6 tokens), and nayige (which object)-questions (5 tokens). Also, non-target like wh-fronting structures were observed. The ungrammatical structures mainly clustered in shenmeshihou (when)-questions, with 10 of the 18 tokens, followed by nail (where)-questions, with 6 of the 30 tokens, increasing the non-target rate to 14% of the total production throughout stage 3. The following example shows the non-target wh-fronting pattern in Mandarin.

*ni3 kan4kan na3il shi4 zhe4ge4? (4;10;20)

you 2SG look where is this CL

(You look where this is?)

Typically, as time goes by, stage 3 should have been the period when GG’s Mandarin

wh-questions became firmly established. However, these target deviant structures prompted us to ponder the reasons for the difference. The highly activated English mode [

46] could prompt the child to use English question paradigms/templates as an expedient measure to organise the Mandarin structure, which we termed ‘bilingual bootstrapping’ [

47].

5.2. The Development of GG’s English Wh-Questions

Table 3 shows that GG’s English

wh-questions emerged much later than their Mandarin counterparts.

What-questions appeared at 3;04;13, followed by

where-questions at 4;00;30 and

who-questions at 4;01;24.

How-questions and

why-questions emerged at 4;03;08 and 4;05;06 respectively. Finally,

when-questions were observed at age 4;06;17. Quite obviously, the six months between age 4;00 and 4;06 witnessed the emergence of all eight types of English

wh-questions.

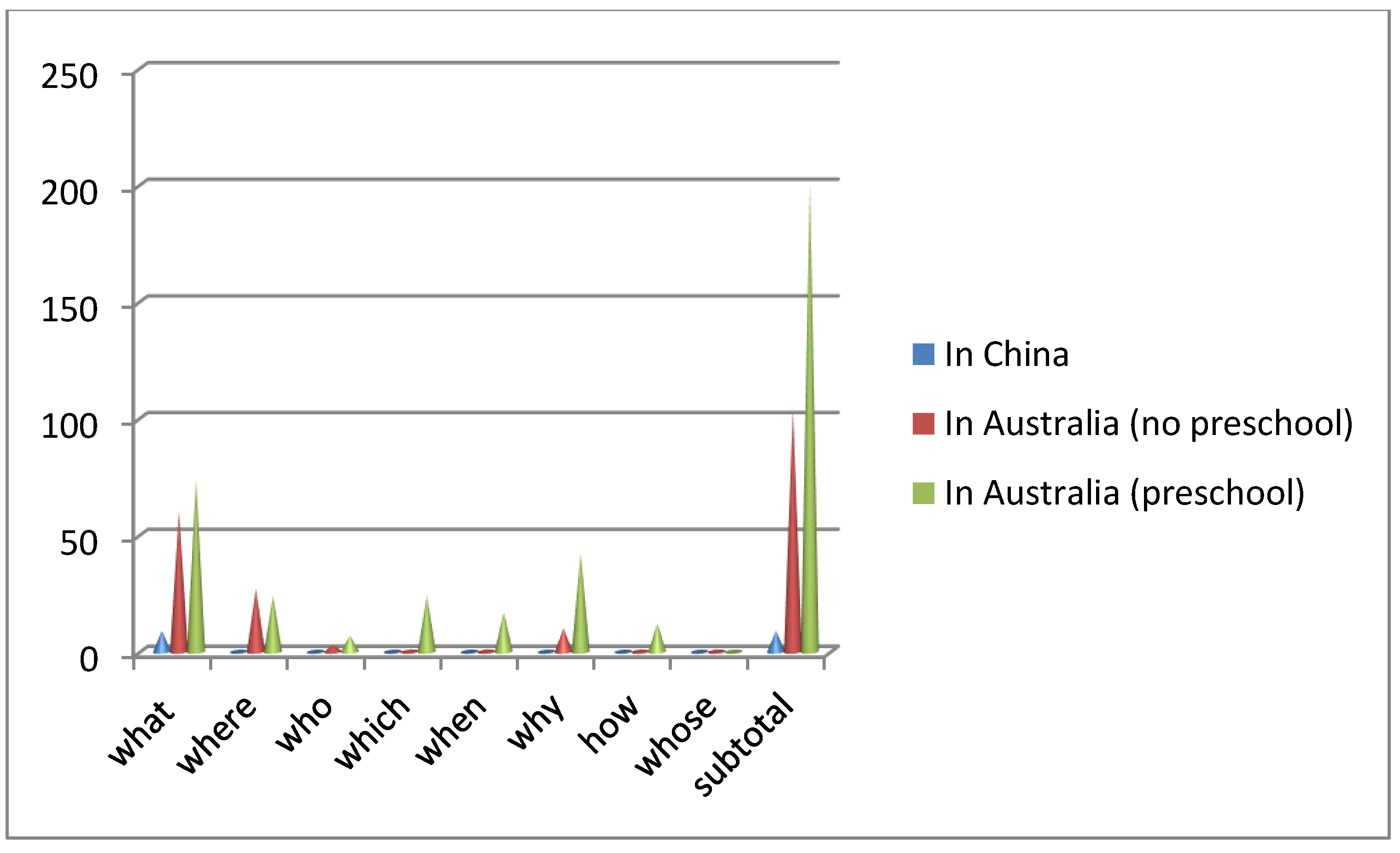

Table 4 and

Figure 2 indicate the distribution of GG’s English

wh-questions over the three stages.

During stage 1, 9 wh-questions were recorded, all of which were what-questions. In stage 2, GG produced 104 wh-questions, among which 60 were what-questions, 27 were where-questions and 10 were why-questions. The following examples show both wh-fronting and wh-in-situ patterns.

What do you think of the logo? (3;09;17)

Why rabbit takes this decoration? (4;04;13)

Time: 17 October 2018.

Age: 4;07;07.

Context: Father was soliciting questions.

FAT: So, I’d like you to ask me question.

CHI: What you like sticker?

FAT: Sorry

CHI: * Do you like what? * You like what sticker?

FAT: I cannot understand you. Could you please repeat?

CHI: * You like what sticker?

It is observed that ungrammatical wh-in-situ English questions emerged at stage 2. The above father-daughter dialogue showed the non-target like structure. The pattern (* You like what sticker?) is actually a precise mapping from the Mandarin wh-in-situ structure onto English, resulting in the cross-linguistic interaction.

GG’s English

wh-question at stage 2 exhibited a 96%

wh-fronting pattern, suggesting a slight quantitative influence from her dominant language (Mandarin). This is similar to Qi and Di Biase [

3], in which English

wh-fronting questions were 100% of the recorded questions. However, it is different from Yip and Matthews [

1], where they reported a systematic cross-linguistic transfer.

At stage 3, GG attended preschool, and accordingly, her English input significantly increased to at least 6 h per day. A total of 201 English wh-questions were recorded: 75 were what-questions, 24 were where-questions and 42 were why-questions, and the three types constituted the majority of her production at this stage. It has indicated that 92% of the English wh-questions were organised into a target-like wh-fronting pattern. The following examples show a variety of her developing questions.

When I want to go to park, why you not take me to? (4;10;20)

* you just want me to paint what things on the paper? (4;10;20)

Why did you not take me to hospital? (5;00;17)

Which colour did they have? (5;02;16)

How do I draw like this, daddy? (5;05:04)

The English question ‘* you want me to draw what things on the paper?’, except for the post verb zai-prepositional phrase, is an exact projection of the Mandarin wh-in-situ pattern onto English.

This non-target pattern could be developmental by nature, in that these structures were only present in complex wh-questions. The finding suggests that the child’s syntactic processing capacity at this stage may not be able to cope with the derivationally complex structures. It is therefore plausible to claim that the child’s transitory production of the non-target like English wh-questions is quantitatively different from her monolingual peers.

5.3. Comparison with Mandarin-English BFLA Child James

Qi and Di Biase’s (2020) [

3] study indicates that the emergence order of the BFLA child James’ Mandarin

wh-questions followed the sequence of

shenme (

what)-questions (2;06;03) and

nali (where)-questions (3;00;14). Due to their focus on the transfer in their research, the emergence order of each remaining Mandarin

wh-word was not presented in their research paper.

With regard to English wh-questions, the emergence order of each wh-word is laid out as what (3;06;02), where (4;01;05), who (4;01;05), and why (4;06;26).

It is found that, in the previous sections, the ESLA child GG’s emergence order of Mandarin wh-questions is what-questions (2;03;04) and where-questions (2;10;17).

The ESLA child’s emergence order of English wh-questions is what (3;04;13), where (4;00;30), who (4;01;24), and why (4;05;06).

Clearly, GG’s Mandarin wh-questions emerged earlier than those of the BFLA child. For shenme (what)-questions, the ESLA child began producing them 13 months earlier and for nali (where)-questions, she was 18 months ahead of the BFLA child.

In terms of English wh-questions, the ESLA child GG showed the same emergence order, with similar emergence timing. The ESLA child GG was 3 months earlier for what-question emergence, but where-questions and who-questions emerged at almost the same time. GG was 50 days ahead of the BFLA child in why-questions. Her what-question emerged 3 months earlier than James’s, but where and who-questions showed similar emergence times. Additionally, her why-questions appeared 50 days ahead of James’s.

In summary, the comparison between the ESLA and the BFLA children suggests that the ESLA child’s Mandarin wh-questions emerged much earlier than the BFLA child’s, whereas both of them shared a similar emergence schedule in various English wh-questions.

The earlier emergence of various Mandarin

wh-questions in the ESLA child may be due to the adequate parental input and the L1 supporting environmental language in China before and during the critical age range for language acquisition (3–4 years of age) [

12,

22]

The ESLA child’s similar emergence timeline of various English

wh-questions to that of the BFLA child James might be due to the prior English exposure as an L2 in the non-supporting environmental language Mandarin. In other words, her pre-existing limited English input at the critical age (around age 3) in China might still have initiated the L2 English acquisition process, and this could explain why GG’s English developmental route was qualitatively similar to that of the BFLA child James. This might further explain why Li Wei’s (2011) [

8] and Hakuta’s (1976) [

9] studies (without prior L2 English input) exhibit systematic transfer, whereas our case only shows slight bilingual interaction. Subjects in Li Wei’s (2011) [

8] and Hakuta’s (1976) [

9] research did not receive L2 English input before moving to English-speaking countries, whereas GG’s L2 English exposure at an early age (1;02) before migration could facilitate her L2 acquisition, thus decreasing the pressure from L1 and minimizing the occurrence of transfer from L1 to L2.

Despite of the above-mentioned similarities and differences, the emergence of both Mandarin and English wh-questions followed the same order: what, where, who and why, suggesting the same developmental route, but different rates between the ESLA and the BFLA children.

5.4. Comparison with Monolingual Mandarin Child Xue’er

Table 5 displays the distribution of the monolingual Mandarin child Xue’er’s

wh-questions from 3;04;01 to 5;05;01.

The table shows that Xue’er produced 113 wh-questions throughout the research period, all of which were wh-in-situ, whereas GG’s data indicate that her wh-in-situ rate is slightly decreasing, especially at stage 3 (86%). GG’s decreasing rate of wh-in-situ might be due to the roles of both the changed environmental language (Lε) and the reduced parental Mandarin input.

5.5. Comparison with Monolingual English Child Adam

Table 6 shows the distribution of the monolingual English child Adam’s

wh-questions from 3;04;18 to 5;02;12.

The table shows that Adam produced 1430 wh-questions throughout the research period, with 98.2% wh-fronting at stage 1, 99.2% at stage 2 and 100% at stage 3. In comparison, GG’s data indicate that her wh-fronting rate was slightly decreasing, especially at stage 3 (92%). GG’s decreasing rate of wh-fronting might be due to her immature processing capacity in configuring complex-English wh-questions. In other words, her English mode was activated in the English Lε, but still had developmental features.

6. Discussion

This study examines the bilingual developmental pathway of wh-questions in an ESLA Mandarin-English bilingual child who moved from China to Australia between the ages of 3;04 and 5;05. Our results suggest that the child’s Mandarin wh-questions were acquired in a target-like manner in China, with 100% of wh-words placed at the in-situ position. After moving to Australia, the child stayed with her parents between ages 3;07 and 4;10 without attending preschool. It was found that her Mandarin wh-questions still displayed a 100% in-situ pattern. After attending preschool, the child’s Mandarin questions started to show a wh-fronting trend, with 14% of non-target production.

Typically, young children’s language acquisition becomes increasingly established as they grow up into middle childhood. However, our data show a slightly different pattern. As the child never produced wh-fronting Mandarin questions in stage 1 and stage 2, this developmental pattern at stage 3 should also have proceeded into stage 3; however, it did not turn out to be the case.

Three factors—age of exposure, input and environmental language—were examined in tandem with each other to account for this acquisition route. At stage 1, the child started to acquire L1 Mandarin from birth in China. This early age of exposure to L1, plus the adequate parental input and the supporting environmental language facilitated the L1 development of this non-pathological child. At stage 2, the child moved to Australia (without attending preschool). The child’s L1 was still developing with adequate L1 input despite the non-supporting English environment. At stage 3, the child attended preschool, and this seems to have played a certain negative role in the child’s L1 development, due to the significantly reduced L1 input and the non-supporting environmental language. Under these linguistic conditions, the child’s L1 mode was inhibited to a certain extent [

46], which could justify the presence of

wh-fronting patterns only in stage 3. To summarise, the child’s Mandarin

wh-questions developed in a similar way to the BFLA child James’s, despite quantitative differences.

With respect to GG’s English wh-question development, it is found that the child produced 100% of wh-fronting questions at stage 1, followed by 96% at stage two and 92% at stage 3. On a superficial note, this developmental trend seems to defy the logic, as the child moved from China to Australia. However, after analysing the data, we found that the ungrammatical wh-in-situ structures only emerged in complex questions, such as long distance wh-questions. These complex linguistic units seem to present a challenge to the child, as she might not be able to process these structures with immature cognitive capacity, thus reversing to her L1 as an expedient and temporary stopgap measure to configure the required syntactic structure in an instantaneous time slot. In other words, the child’s L2 English wh-questions developed in a similar manner to the BFLA child James’s, despite slight quantitative differences.

Based on our data and discussion, we can answer the research questions.

For Research Question 1, the emergence order of the ESLA child GG’s English

wh-questions resembles that of BFLA child James [

3]. GG’s English acquisition route was similar to that of James, but the rate (regarding the proportion of

wh-words position) was slightly different. Observation after 5;05 suggests that GG’s English

wh-questions were problem-free in all syntactic structures, including single clauses, embedded clauses and attributive clauses. In addition, GG’s English-question developmental trajectory is qualitatively different from those cases reported in Yip and Matthews [

4]. This may be due to the fact that their children’s dominant language (Cantonese) coincides with the environmental language in Hong Kong, reinforcing the dominance of Cantonese and triggering massive transfer from Cantonese to English.

For Research Question 2, GG’s emergence order of Mandarin

wh-questions is similar to that of James, but the rate (regarding the percentage of

wh-word position) is slightly different. This could be justified by the fact that Mandarin is the dominant language for both GG and James, thus they share a similar route. The rate differences might be due to the unavailability of complex

wh-questions in James’s data, thus widening the gap between the two children. Our study is qualitatively similar to but quantitatively different from Qi & Di Biase [

3], where they claimed that the transfer-free bilingual development could be caused by the reinforcement of Lε of the weaker language (English).

For Research Question 3, it is found that the changed Lε English seems to play a supportive role in GG’s English wh-question profile, as constant presence of the wh-fronting pattern is observed, despite a slight cross-linguistic influence and certain non-target like developmental errors. Lε English appears to exert a less supporting influence on Mandarin: the constant wh-fronting pattern in the Lε could inhibit the L1 Mandarin wh-in-situ structure and trigger cross-linguistic influences, which was proved by certain wh-fronting Mandarin patterns at stage 3.

Riham’s (2023) [

21] study reported a significant proportion of transfer from L2 English to L1 Arabic, suggesting that the later age of exposure to L2 with adequate L2 input (long residence) may still exert an influence on L1 even if L1 is established. Whereas our study indicates a slight bi-directional cross-linguistic influence, this could be explained by the prior L2 input before migration. In other words, the early age of first exposure to English may increase the bilingual child’s sensitivity towards L2 sysntax and lay the foundation of sound bilingual development in the future.

The results could have some pedagogical implications for early childhood bilingual acquisition. First, ESLA children’s L1 should be maintained by sustained parental input and ongoing community language support in L2 countries. Typically, maintaining their L1 could be realised not only by Saturday schools, but also some homeschooling and cultural immersion programs. Second, parents do not need to take educational actions regarding their L2 development, even if young children display some non-target structures, as the environmental language (Lε) could promote their overall L2 acquisition towards skillful and productive use in due course.