The Transformative Potential of Gender Equality Plans to Expand Women’s, Gender, and Feminist Studies in Higher Education: Grounds for Vigilant Optimism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Gender Equality Plans as a Strategy for Strengthening WGFS in Higher Education

2.2. The State of the Art of Integrating WGFS into HE Curricula in Portugal

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Documentary Analysis: Gender Equality Plans

3.2. Semi-Structured Individual Interviews

3.3. Questionnaire Survey

3.4. Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches

4. Results and Discussion

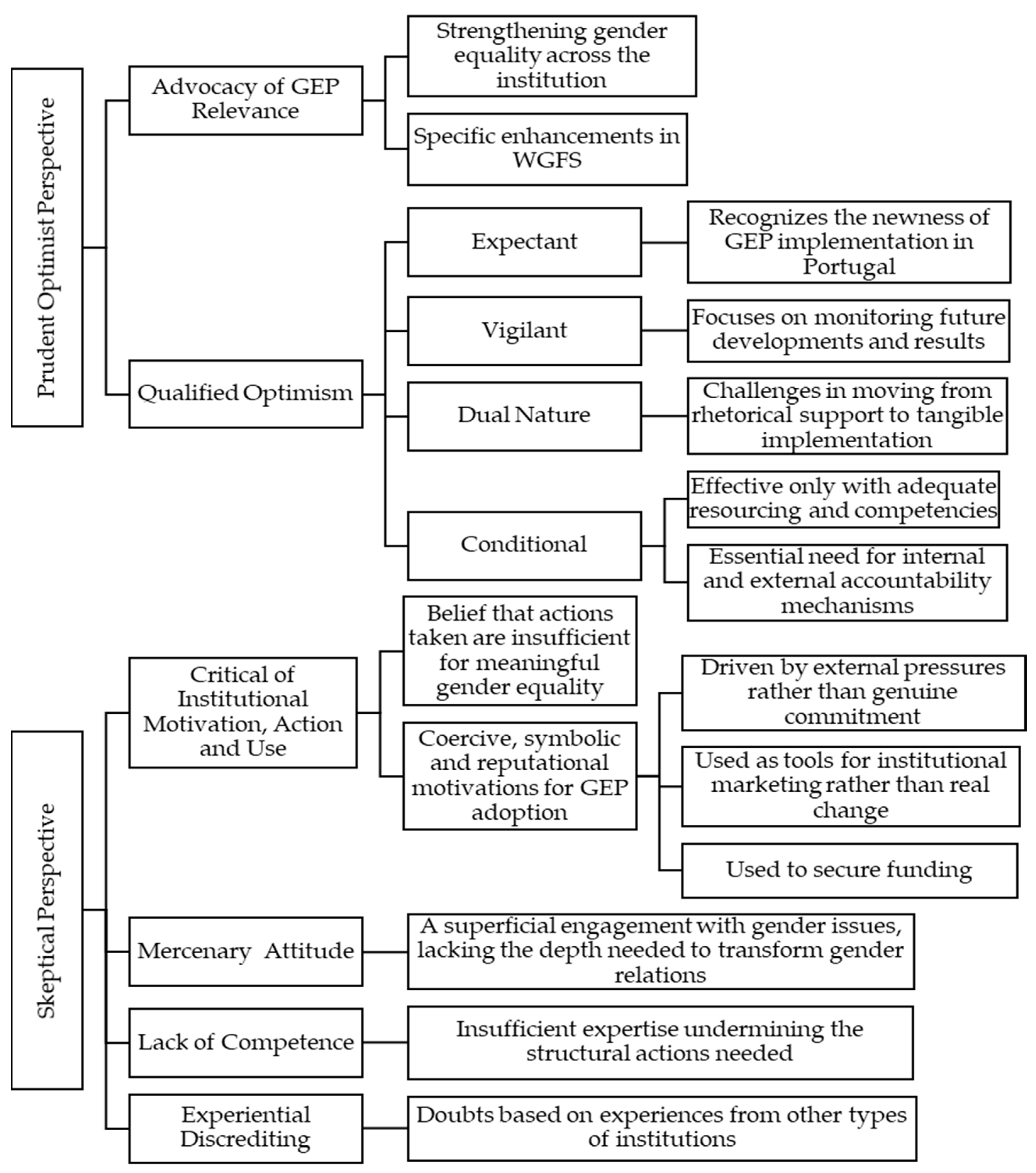

4.1. Building Profiles of Representations about GEPs

4.1.1. Cautious Optimistic Perspective

We know that a plan doesn’t solve everything. (...) it’s not the plan that’s going to change everything, but the plan is an instrument for change and it’s important that it exists. It makes these issues visible in a way, puts them on the agenda, which is an important thing, and then this change has to be achieved with everyone.(WGFS Program lecturer, 12)

The plan is very recent, it was approved just this month, so we still don’t know how... But we do know that.... I’m aware that it was drawn up precisely because of this external constraint (...) Let’s see its effects. We know that in terms of equality, progress is made a lot due to external constraints, legislation, policies, guidelines, and Portugal is a very good student, it’s a country that, in fact, follows many guidelines and has very strong policies in terms of legislation. We have great legislation, but then, as everyone knows, the real problem is implementing it, putting it into practice.(WGFS Program lecturer, 13)

But it’s always a problem with plans whether it’s just a narrative or whether it’s consequent. (...) (...)I hope it’s not just rhetoric. There’s debate, there’s a network set up...(Founder/coordinator of WGFS program, 1)

I understand the discussion, but the discussion is a bit like regulating quotas. It’s exactly the same thing. Is it cosmetic or is it profound? Do we want it to be cosmetic or deep? And from a certain point of view, in the abstract, I could even say “oh, the quotas”. (...) The fact that the plan exists inevitably brings about change (...) People must at least look like they care about these issues. If they start off looking like it, then they’ll convert or if they never convert, but as well as looking like it, they have to show some practical work.(WGFS Program lecturer, 9)

But there is an evolution, very slow, but there is some. And I have some hope, because we always operate in this coercive isomorphism, that this obligation to have equality plans, for funding, will change, that it will introduce some more transformative force from the point of view of the institutions. (...) I always like to have some optimism about the processes underway, but I also know that when there is no coercion, when there is no imposition, things are often diluted. That’s why I was talking earlier about a directive or a superior guideline on accreditation. I think that if it doesn’t happen that way, it really will take a long time to happen.(founder/coordinator of WGFS Program, 1)

We have the national plans themselves, which I think are very interesting public tools. And I think the question of the equality plans that the institutions themselves must have, the question of A3ES, now, of evaluation.... What would be important for me would be for the very funding that exists in Portugal for research to valorize this issue of Gender Studies.(WGFS Program lecturer, 13)

And the institutions answer to whom? So, who do they answer to when they plan? They don’t have to report on its implementation. But even so, I mean, at least we could see a network that brings together people from the various organizational units. The pressure should also be applied within each institution.(founder/coordinator of WGFS Program, 1)

The equality plan is being made by people who have the right positions, feminists, etc. (...) Ours is being made by people from X [University] who have always worked on gender, either in psychology or sociology, ... (...) We’re a group of people who have always been linked to gender, so we don’t just fall over ourselves, do we? This plan for equality is being made with the people who work on gender at the university.(founder/coordinator of WGFS Program, 5)

4.1.2. Skeptical Perspective

Institutions use gender equality mainly to appear democratic and modern, but they’re not at all. It’s only equality on paper.(Assistant Professor, public university education, 56 years old)

We’ll definitely have an equality plan. It’s fool proof because without it you won’t be able to get funding. It will probably produce some results too. I don’t doubt that, but until I see it, I have some doubts about the degree of integration and effectiveness that this plan will have. Because we need something more in-depth here, not just one-off measures, and I don’t see that happening. But I hope I’m wrong and, in a year or two, I’ll be giving good news. (...) As a friend of mine says, “systems inertia is very powerful”. (...) There are other things that always seem to be more pressing, and so that is always secondary.(founder/coordinator of WGFS Program, 4)

The problem, as with everything, is this: we’re good at making laws and plans. (...) When we look at a plan like this, the first thing that comes to mind is: the additional work, the additional burden that this is going to bring to our agendas. (...) In terms of defining the objective, the concern, recognizing the problem and the need for action, everything is fine. The problem is allocating resources to it.(WGFS Program lecturer, 8)

Universities must have an equality plan. Yeah, well, so do local councils and we know how it works, don’t we? Because I can have a plan for equality and that doesn’t mean that it will then materialize in concrete actions, in a change in people’s ways of thinking and acting and in concrete policies that allow for gender equality. And I don’t see that happening. (...) I may be wrong, and something very well-structured and very integrated may be being prepared, but there is still too much of this idea that this is a job that must be done.(WGFS Program lecturer, 15)

I know because I’ve witnessed and been able to observe teams—I’m not talking about the university, but maybe the university too, I’m not saying it’s not—but teams at the local authority level with projects approved to implement plans, where the people in charge of it don’t even know their names. The likelihood of these equality plans being the biggest crock of shit on the face of the earth and just money thrown away is high. I think that, at the moment, if in a way it was important in political terms—now there is no money for anything if there are no gender equality concerns—that on the one hand is good, but if people think that this can be done without any kind of regulation, they must be dreaming.(founder/coordinator of WGFS Program, 5)

There has been growing funding linked to equality plans and equality areas. Particularly in municipalities, in other contexts. And many people weren’t sensitized to equality issues and didn’t want to work on equality issues. But money was coming in. So, as European money was coming in, people started working.(WGFS Program lecturer, 10)

Why are universities making plans for equality now? Because of the European requirement, otherwise, they won’t get funding. (...) (...) Nobody knows anything, but everyone has something to say.(interview with founder/coordinator of WGFS Program, 6)

4.1.3. Simplistic/Passive/Resistant Perspective

4.2. Limited Strategies and Lines of Action for Integrating the Gender Perspective into Curricula and Teaching Practices

I think the disadvantage of separate, independent WGFS programs is that it conveys the idea that this is an area that isn’t transversal and is part of the specific interests of a ‘minority’.(WGFS program founder/coordinator, 2).

Where I think these themes can have a more transformative impact is in disciplinary programs not specific to WGFS. (...) I think it’s in these disciplinary courses that the transformative potential is greatest because there a question is introduced that has never been asked before.(WGFS program lecturer, 12).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Opinions on the GEPs and the Institutional Initiative to Strengthen the WGFS—Statistical Summary

| Statements | Mean | SD | Median | Mode |

| 1. It’s something that HEIs create, but it’s not part of their operational priorities | 5.1 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| 2. It is an important mechanism for integrating gender content into curricula | 5.1 | 1.1 | 5 | 6 |

| 3. It is easily implemented | 4.8 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| 4. It’s irrelevant to raising teachers’ awareness of gender inequalities | 4.8 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| 5. It is a tool for assessing inequalities in terms of gender, sexual orientation, racial/ethnic origin, and religion | 4.6 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| 6. It creates a more favorable internal environment for the development of WGFS in teaching and research | 4.2 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| 7. When evaluating educational institutions, the Higher Education Accreditation and Evaluation Agency (A3ES) should include gender equality in the criteria | 3.2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 8. It is an important mechanism for reviewing and transforming institutional procedures and practices that reproduce inequalities in higher education careers | 3.1 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| 9. The institution where I teach has been silent on initiatives to integrate GD into teaching | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| 10. My institution has been silent on initiatives to support the integration of GD into research projects | 2.4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

References

- Ferreira, V. Estudos sobre as Mulheres em Portugal: A construção de um novo campo científico (Women’s Studies in Portugal: The construction of a new scientific field). Ex Aequo 2001, 5, 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Joaquim, T. ex æquo: Contributo decisivo para um campo de estudos em Portugal (ex æquo: Decisive contribution to a field of study in Portugal). Rev. Estud. Fem. 2004, 12, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lopes, M.; Santos, C.; Ferreira, V. Modalidades e Graus de Integração dos Estudos sobre as Mulheres, de Género e Feministas no Ensino Superior Português: Uma Análise Sistemática dos Currículos (Modalities and degrees of integration of women’s, gender and feminist studies in portuguese higher education: A systematic analysis of curricula). Faces De Eva. Estud. Sobre A Mulher 2023, 50, 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Văcărescu, T. Uneven curriculum inclusion: Gender studies and gender IN studies at the University of Bucharest. In From Gender Studies to Gender in Studies: Case Studies on Gender-Inclusive Curriculum in Higher Education; Grünberg, L., Ed.; UNESCO-CEPES: Bucharest, Romania, 2011; pp. 147–184. [Google Scholar]

- Grünberg, L. From Gender Studies to Gender in Studies: Case Studies on Gender-Inclusive Curriculum in Higher Education; UNESCO-CEPES: Bucharest, Romania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pető, A.; Dezső, D. Teaching gender at the Central European University: Advantages of internationalism. In From Gender Studies to Gender in Studies: Case Studies on Gender-Inclusive Curriculum in Higher Education; Grünberg, L., Ed.; UNESCO-CEPES: Bucharest, Romania, 2011; pp. 103–145. [Google Scholar]

- González, F.J.; Guarinos, V.; Cobo-Durán, S. Gender competences in undergraduate studies in Spanish public universities. Case study of the University of Seville. J. Multicult. Educ. 2021, 15, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, C.C. A dimensão de género nos curricula do Ensino Superior: Factos e reflexões a partir de uma entrevista focalizada de grupo a especialistas portuguesas no domínio (The gender dimension in higher education curricula: Facts and reflections from a focused group interview with Portuguese experts in the field). Ex Aequo 2007, 16, 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M.M. Power, Knowledge and Feminist Scholarship: An Ethnography of Academia; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abranches, G. On what terms shall we join the procession of educated men? Teaching Feminist Studies at the University of Coimbra. Oficina Do CES 1998, 125, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, C.; Monteiro, R.; Lopes, M.; Martinez, M.; Ferreira, V. From Late Bloomer to Booming: A Bibliometric Analysis of Women’s, Gender, and Feminist Studies in Portugal. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmén, J.; Ringarp, J. Public, private, or in between? Institutional isomorphism and the legal entities in Swedish and Finnish higher education. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2022, 9, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P. Athena SWAN: Why is it so difficult to reduce gender inequality in male-dominated higher educational organizations? A feminist institutional perspective. Interdiscip. Sci. Rev. 2020, 45, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.; Powell, W. Introduction: The New Institutionalism and Organizational Analysis. In The New Institutionalism and Organizational Analysis, 2nd ed.; DiMaggio, P., Powell, W., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kortendiek, B. Supporting the Bologna process by gender mainstreaming: A model for the integration of gender studies in higher education curricula. In From Gender Studies to Gender in Studies: Case Studies on Gender-Inclusive Curriculum in Higher Education; Grünberg, L., Ed.; UNESCO-CEPES: Bucharest, Romania, 2011; pp. 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Gender Mainstreaming: Conceptual Framework, Methodology and Presentation of Good Practices; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). Gender Equality in Academia and Research: GEAR Tool, 1st ed.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Palmén, R.; Schmidt, E. Analysing Facilitating and Hindering Factors for Implementing Gender Equality Interventions in R&I: Structures and Processes. Eval. Program Plan. 2019, 77, 101726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A Reinforced European Research Area Partnership for Excellence and Growth (European Commission Communication No. COM/2012/0392); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bencivenga, R.; Drew, E. Promoting gender equality and structural change in academia through gender equality plans: Harmonising EU and national initiatives. GENDER–Z. Für Geschlecht Kult. Und Ges. 2021, 13, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergaert, L.; Cacace, M.; Linková, M. Gender Equality Impact Drivers Revisited: Assessing Institutional Capacity in Research and Higher Education Institutions. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiebinger, L. Gender-Responsible Research and Innovation for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Nanotechnology, ICT, and Healthcare. 2017. Available online: https://innovation-compass.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Londa-Schiebinger_Gender-Responsible-Research-and-Innovation.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Linkova, M.; Mergaert, L. Negotiating change for gender equality: Identifying leverages, overcoming barriers. Investig. Fem. 2021, 12, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantola, J.; Lombardo, E. Gender and the Economic Crisis in Europe: Politics, Institutions and Intersectionality; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, L. Analytical Review: Structural Change for Gender Equality in Research and Innovation; Ministry of Education and Culture: Helsinki, Finland, 2021; Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-263-880-9 (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- European Commission. Horizon Europe Guidance on Gender Equality Plans (GEPs); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). Gender Equality in Academia and Research: GEAR Tool, 2nd ed.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Verge, T. Gender Equality Policy and Universities: Feminist Strategic Alliances to Re-gender the Curriculum. J. Women Polit. Policy 2021, 42, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Research Area and Innovation Committee (ERAC). Report by the ERAC SWG on Gender in Research and Innovation on Gender Equality Plans as a Catalyst for Change; ERAC: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Clavero, S.; Galligan, Y. Analysing gender and institutional change in academia: Evaluating the utility of feminist institutionalist approaches. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2020, 42, 650–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostou, D. EU Policy and Gender Mainstreaming in Research and Higher Education: How Well Does it Travel from North to South? In Overcoming the Challenge of Structural Change in Research Organisations—A Reflexive Approach to Gender Equality; Wroblewski, A., Palmén, R., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2022; pp. 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Palmén, R.; Arroyo, L.; Müller, J.; Reidl, S.; Caprile, M.; Unger, M. Integrating the Gender Dimension in Teaching, Research Content & Knowledge and Technology Transfer: Validating the EFFORTI Evaluation Framework through Three Case Studies in Europe. Eval. Program Plan. 2020, 79, 101746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cois, E.; Naldini, M.; Solera, C. Addressing Gender Inequality in National Academic Contexts. Sociologica 2023, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, L.; Pardo, M.; Dasi, A. The institutional isomorphism in the context of organizational changes in higher education institutions. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2020, 6, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A3ES. Manual Para o Processo de Avaliação Institucional no Ensino Superior 2022, 3rd ed.; Agency for Assessment and Accreditation of Higher Education: Lisbon, Portugal, 2022; Available online: https://www.a3es.pt/pt/acreditacao-e-auditoria/guioes-e-procedimentos/avaliacao-institucional (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Human Resources Strategy for Researchers (HRS4R). Available online: https://euraxess.ec.europa.eu/jobs/hrs4r (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Monteiro, R. Estado, Movimentos de Mulheres e Igualdade de Género em Portugal: Fases e Metamorfoses, 3rd ed.; Comissão para a Cidadania e Igualdade de Género: Lisboa, Portugal, 2017; pp. 154–196. ISBN 978-972-597-412-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M.d.M. Higher Education Cutbacks and the Reshaping of Epistemic Hierarchies: An Ethnography of the Case of Feminist Scholarship. Sociology 2015, 49, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, S.; Tauch, C. Trends IV: European Universities Implementing Bologna; European University Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M.M. A institucionalização dos estudos sobre as mulheres, de género e feministas em Portugal no século XXI: Conquistas, desafios e paradoxos (The institutionalization of women’s, gender and feminist studies in Portugal in the 21st century: Achievements, challenges and paradoxes). Faces Eva Estud. Sobre Mulh. 2013, 30, 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, G. The institutionalization of women’s studies in Europe. In Doing Women’s Studies: Employment Opportunities, Personal Impacts, and Social Consequences; Griffin, G., Ed.; Zed: London, UK, 2005; pp. 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- Silius, H. Women’s employment, equal opportunities and women’s studies in nine European countries—A summary. In Women’s Employment, Women’s Studies, and Equal Opportunities 1945–2001; Griffin, G., Ed.; University of Hull: Hull, UK, 2002; pp. 15–64. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Heide, A.; van Arensbergen, P.; Bleijenbergh, I.; Lansu, M. Collected Good Practices in Introducing Gender in Curricula (EGERA Deliverable No. D.4.4.); EGERA Project. 2017. Available online: https://www.egera.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Deliverables/D44_Collected_Good_Practices_in_Introducing_Gender_in_Curricula_78106.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Verge, T.; Ferrer-Fons, M.; González, M.J. Resistance to mainstreaming gender into the higher education curriculum. Eur. J. Women’s Stud. 2018, 25, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, C.C. Gender dimensions in Portuguese academia: An erratic relationship between political intentions and curricula priorities. In Considering Gender in Adult Learning and in Academia: (In) Visible Act; Ostrouch-Kaminska, J., Fontanini, C., Gaynard, S., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Dolnośląskiej Szkoly Wyższej: Wroclaw, Poland, 2012; pp. 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, V. Estudos de Género na universidade performativa (Gender studies in the performative university). In Proceedings of the XIII Congreso Español de Sociología, Valencia, Spain, 3–6 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kahlert, H. (Ed.) Gender Studies and the New Academic Governance: Global Challenges, Glocal Dynamics and Local Impacts, 3rd ed.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, T.; Diogo, S. Formalised Boundaries Between Polytechnics and Technical Universities: Experiences from Portugal and Finland. In Technical Universities, 2nd ed.; Geschwind, L., Broström, A., Larsen, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 56, pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindkvist, K. Approaches to textual analysis. Adv. Content Anal. 1981, 9, 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Leidner, R. Fast Food, Fast Talk: Service Work and the Routinization of Everyday Life; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA; Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Amado, J. Manual de Investigação Qualitativa em Educação (Handbook of Qualitative Research in Education), 3rd ed.; Coimbra University Press: Coimbra, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Gutmann, M.; Hanson, W. Advanced mixed methods research designs. In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research, 2nd ed.; Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.; Powell, W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprile, M.; Bettachy, M.; Duhaček, D.; Mirazić, M.; Palmén, R.; Kussy, A. Structural change towards gender equality: Learning from bottom-up and top-down experiences of GEP Implementation in universities. In Overcoming the Challenge of Structural Change in Research Organisations—A Reflexive Approach to Gender Equality; Wroblewski, A., Palmén, R., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2022; pp. 161–179. [Google Scholar]

- Tildesley, R.; Lombardo, E.; Verge, T. Power Struggles in the Implementation of Gender Equality Policies: The Politics of Resistance and Counter-resistance in Universities. Polit. Gend. 2022, 18, 879–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustelo, M.; SUPERA Partners. Guidelines and Best Practices for RPOs (SUPERA Deliverable No. D.5.3.); SUPERA Project. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5f20826e8&appId=PPGMS (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Kantola, J.; Squires, J. From state feminism to market feminism? Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2012, 33, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- True, J. Mainstreaming Gender in Global Public Policy. Int. Fem. J. Polit. 2003, 5, 368–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, E.; Mergaert, L. Gender mainstreaming and resistance to gender training: A framework for studying implementation. NORA-Nord. J. Fem. Gend. Res. 2013, 21, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, P. Implementing Gender Equality: Gender Mainstreaming or the Gap between Theory and Practice. In Women’s Citizenship and Political Rights; Hellsten, S.K., Maria, H.A., Daskalova, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 179–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan, C. Gender mainstreaming: Failings in implementation. Kvinder Køn Forsk. 2011, 1, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cavaghan, R. GM Bridging Rhetoric and Practice: New Perspectives on Barriers to Gendered Change. J. Women Polit. Policy 2017, 38, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vida, B. Policy framing and resistance: Gender mainstreaming in Horizon 2020. Eur. J. Women’s Stud. 2021, 28, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wroblewski, A.; Palmén, R.A. A reflexive approach to structural change. In Overcoming the Challenge of Structural Change in Research Organisations—A Reflexive Approach to Gender Equality; Wroblewski, A., Palmén, R., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2022; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Collado, C.C.; Vázquez-Cupeiro, S. Resistance and counter-resistance to gender equality policies in Spanish universities. Papers 2023, 108, e3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.; Rodrigues, F. Between Knowledge and Power: Implementing a Gender Institutional Change Project in Academia. In Estudos de Género, Feministas e Sobre as Mulheres: Reflexividade, Resistência e ação; Torre, A., Costa, D., Maciel, D., Pinto, T.J., Eds.; Edições ISCSP: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023; pp. 445–460. [Google Scholar]

| No. HEIs | No. HEIs with GEP | % HEIs with GEP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private | 63 | 10 | 15.9 |

| Public | 34 | 28 | 82.4 |

| Polytechnic | 62 | 19 | 30.6 |

| University | 35 | 19 | 54.3 |

| TOTAL | 97 | 38 | 39.2 |

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 1 | 2.2 |

| 2021 | 11 | 24.4 |

| 2022 | 27 | 60.0 |

| 2023 | 6 | 13.3 |

| Total | 45 | 100.0 |

| Statements about Institutional Initiative/GEP | Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A—Optimistic | B—Skeptical | C—Simplistic | |

| 1. It’s something that HEIs create, but it’s not part of their operational priorities | −0.002 | 0.661 | −0.116 |

| 2. It is an important mechanism for integrating gender content into curricula | 0.629 | 0.218 | 0.222 |

| 3. It is easily implemented | 0.035 | −0.073 | 0.893 |

| 4. It’s irrelevant to raising teachers’ awareness of gender inequalities | −0.680 | 0.176 | 0.403 |

| 5. It is a tool for assessing inequalities in terms of gender, sexual orientation, racial/ethnic origin, and religion | 0.763 | 0.082 | −0.179 |

| 6. It creates a more favorable internal environment for the development of WGFS in teaching and research | 0.857 | −0.145 | 0.137 |

| 7. When evaluating educational institutions, the Higher Education Accreditation and Evaluation Agency (A3ES) should include gender equality in the criteria | 0.541 | 0.265 | −0.381 |

| 8. It is an important mechanism for reviewing and transforming institutional procedures and practices that reproduce inequalities in higher education careers | 0.860 | 0.111 | 0.037 |

| 9. The institution where I teach has been silent on initiatives to integrate gender dimension into teaching | 0.156 | 0.774 | 0.111 |

| 10. My institution has been silent on initiatives to support the integration of gender dimension into research projects | −0.007 | 0.825 | −0.076 |

| Eigenvalue | 3.233 | 1.911 | 1.238 |

| Variance explained | 32.3% | 19.1% | 12.4% |

| Types of Measures | No. Measures |

|---|---|

| Gender in teaching content | |

| Integrating the gender dimension into degree programs/courses | 18 |

| Development of gender-specific modules/courses | 15 |

| Training and capacity building | |

| Training for teachers/course coordinators | 9 |

| Guides/guidelines for gender mainstreaming | 3 |

| Communication and awareness raising | |

| Raising awareness/dissemination among students/academic community | 6 |

| Teacher awareness and dissemination efforts | 5 |

| Gender in teaching methods | |

| Incorporation of inclusive language | 1 |

| Introduction of new pedagogical methodologies/models | 1 |

| Change in gender-relevant provisions and procedures | |

| Implementation of gender criteria for teaching awards | 1 |

| Integrating gender dimension into student satisfaction surveys | 1 |

| Structures for integrating gender dimension into teaching (e.g., working groups, committees) | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopes, M.; Santos, C.; Ferreira, V.; Monteiro, R.; Vieira, C.C. The Transformative Potential of Gender Equality Plans to Expand Women’s, Gender, and Feminist Studies in Higher Education: Grounds for Vigilant Optimism. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080889

Lopes M, Santos C, Ferreira V, Monteiro R, Vieira CC. The Transformative Potential of Gender Equality Plans to Expand Women’s, Gender, and Feminist Studies in Higher Education: Grounds for Vigilant Optimism. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(8):889. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080889

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopes, Mónica, Caynnã Santos, Virgínia Ferreira, Rosa Monteiro, and Cristina C. Vieira. 2024. "The Transformative Potential of Gender Equality Plans to Expand Women’s, Gender, and Feminist Studies in Higher Education: Grounds for Vigilant Optimism" Education Sciences 14, no. 8: 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080889

APA StyleLopes, M., Santos, C., Ferreira, V., Monteiro, R., & Vieira, C. C. (2024). The Transformative Potential of Gender Equality Plans to Expand Women’s, Gender, and Feminist Studies in Higher Education: Grounds for Vigilant Optimism. Education Sciences, 14(8), 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080889