Abstract

The post-pandemic era shaped by COVID-19 has compelled universities to reimagine their learning experiences, adapting to new educational requirements and heightened expectations. However, this transformation brings forth novel pedagogical requirements and learning limitations. In today’s educational landscape, learners seek active and relevant learning experiences that seamlessly integrate interactivity, crisis awareness, and global challenges tied to a resilience and sustainability perspective. To address this imperative, our work introduces an experiential learning lab to articulate Kolb’s experiential learning cycle and authentic assessment principles. By incorporating real-world events as study scenarios, higher-order skill challenges, and self-regulated learning in alignment with reflective and practical activities, we aim to enhance students’ engagement and learning relevance. To illustrate practical implementation, we propose a case study methodology regarding an experiential learning lab for operations management education. Specifically, we delve into a case study centred around the Social Lab for Sustainable Logistics, involving a circular economy challenge as a learning experience during the post-COVID-19 pandemic. Preliminary results indicate that the experiential learning lab helped to create the learning experience in alignment with intended learning outcomes. However, further instances of such learning experiences are necessary to explore the contribution and applicability of the lab across diverse settings and disciplines.

1. Introduction

This article delves into experiential learning labs for business management education to address novel educational requirements in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic caused unprecedented disruptions and massive changes, leading to the need for curriculum adaptations, student-centred pedagogical approaches, and the capitalisation of different instruction methods [1]. This view demands a novel perspective to upscale learning experiences in higher education (HE) under the new circumstances.

Nowadays, HE requires active approaches for effective learning and student engagement [2]. In this sense, diverse pedagogies have been offered concerning reflective and practical learning and the development of intended learning outcomes [3]. However, during disruptive events, such as human-made or natural disasters, or because of these, conventional teaching and learning activities are transitioned to extraordinary educational settings. Consequently, this type of change limits learners’ interactions, access to educational facilities, and availability of learning resources and infrastructure, jeopardising learning achievements and demanding further adaptations.

During the recent COVID-19 pandemic, sanitary restrictions affected the accomplishment of learning objectives and outcomes, reshaped pedagogical designs, impinged upon tutors’ and learners’ involvement, changed participants’ expectations, disrupted learners’ interactions and socialisation, and transformed the learning spaces [4,5,6,7]. In this context, the novel education difficulties demanded a shift in education value propositions and delivery methods [8].

Before the pandemic, some educational changes were never fully realised in HE such as the need for developmental, personalised, and evolving curricula; active and purposeful pedagogies; and ubiquitous learning [1]. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, these requirements are still valid [9]. Previous research showed that novel learning scenarios require prompt transformations in learning environments, overcoming existing obstacles, and the implementation of effective pedagogical interventions [10]. These adjustments comprise a constructive alignment of intended learning outcomes and active learning pedagogies, aiming to equip students with practical and high-order skills [11,12]. Additionally, further modifications are needed to increase learning relevance and applicability so that learners’ value perception is increased [10].

In this sense, after the pandemic, universities have implemented diverse strategies to redefine teaching and learning activities and adapt to novel learning needs and expectations [13]. For instance, hybrid and blended learning alternatives have been used for remote learning incorporating video demonstrations, simulation games, virtual laboratories, and other web-based tools [14]. Moreover, in some cases, universities have also rethought and changed their learning activities and assessments to enhance authentic assessment with methods that overcome concerns about learning ingenuity and academic integrity [15,16]. These include, for instance, remote proctoring, lockdown web browsers, and practical projects, among others.

Additionally, because of the pandemic disruptions and post-effects, there is a need to increase learning interactivity and knowledge creation around a crisis and resilience perspective on sustainability and global challenges [17]. There also exists a renewed necessity for pedagogical approaches to amplify student interest, motivation, and engagement in courses [1,6,18]. Overall, this points to developing capabilities for educational response and continuity and improving the well-being and performance of learners.

Accordingly, a problem definition in this work regards the pedagogical needs in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era to provide students with a crisis and resilience perspective on global challenges and engaging learning. Therefore, this work aims to develop an educational platform for operations management education to recreate learning experiences that tackle relevant real-world contemporary challenges for the attainment of intended learning outcomes and the enhancement of student interest, motivation, and engagement.

Previous work suggests the possibility of recreating this type of experience based on experiential learning as it articulates a continuous process of thinking and acting as part of an effective learning process [19,20,21]. This proposition calls for learners perceiving, reflecting, conceptualising, and experimenting in situated settings [22,23]. Moreover, it also considers the possibility of considering authentic assessment to face the complex nuances of genuine higher-order and practical learning [24,25]. Consequently, current post-COVID-19 education requirements can define real-world scenarios to be translated into purposeful experiential and authentic assessment types of learning activities [26].

Experiential learning and authentic assessment play a central role in this context to underscore the importance of active student engagement in constructing knowledge and attaining desired learning outcomes. From a constructionist standpoint, these approaches cultivate profound comprehension, critical thinking, and hands-on participation among students, rendering them a valuable enhancement for both in-person and remote learning experiences [21].

Accordingly, a working hypothesis is proposed to guide the research efforts of this work as follows.

Learning experiences, focused on experiential learning and authentic assessment, can enhance student engagement, motivation, and the attainment of learning outcomes. By offering these learning experiences with a crisis and resilience perspective on global challenges, these address the educational needs of the post-COVID-19 era.

Hence, this work comprises six sections. Section 2 provides the conceptual foundations of this work concerning experiential learning and authentic assessment and describes the main proposition of this work concerning experiential learning labs. Section 3 outlines the methodology for a case study of an experiential learning laboratory. Section 4 reports results from a supply chain management and logistics (SCML) experiential learning lab case study focusing on sustainability and food supply within the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Supply Chain Management and Logistics Excellence Network (MIT SCALE Network) for Latin America and the Caribbean. This lab advances the conceptualisation of relevant learning activities for industrial engineering education, exploring disciplinary implications and the effects on student interest, motivation, and engagement. Section 5 engages in the discussion of results, identifying main findings, limitations, and future work. Finally, Section 6 concludes the work, summarising key insights and takeaways.

2. Background

Addressing the challenges of the post-pandemic requires supportive teaching, learning, and assessment activities aligned with novel realistic environments to maintain student interest, motivation, and engagement [22,27]. This view points to the redefinition of instructional designs for learning experiences [7]. That is, experiences that transform learners’ perceptions, facilitate conceptual understanding, yield emotional qualities, and nurture competencies acquisition [28]. Hence, this work proposes the development of experiential learning laboratories (or labs) linked to the integration of experiential learning, authentic assessment, and real-world challenges to enhance learnability. A further elaboration of these foundational notions is provided in the following sections.

2.1. Experiential Learning for Authentic Assessment

Experiential learning emerges as a highly effective pedagogical approach for fostering authentic and impactful learning in HE. Mirroring real-world situations, experiential learning enables students to gain relevant knowledge and develop essential skills for their future professional careers through direct experiences and active engagement in diverse scenarios [21,29]. Grounded in Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, this approach involves a continuous process of meaning-making through concrete experiences (CE), reflective observation (RO), abstract conceptualisation (AC), and active experimentation (AE) [30].

Authentic assessment aligns seamlessly with the principles of experiential learning by presenting students with realistic, contextualised scenarios that resemble professional practice or real-life challenges [31]. Rather than relying on indirect or oversimplified assessments, authentic assessments demand that learners apply their knowledge and skills to confront complex, open-ended tasks reflecting the ambiguities and intellectual difficulties found in the real world [32].

Through experiential learning activities, students undergo iterative cycles of practical experiences, reflection, conceptualisation, and experimentation, cultivating the very abilities that authentic assessments aim to evaluate [23,30]. Authentic assessments serve as culminating performance-based evaluations, providing students with opportunities to showcase their comprehension, problem-solving prowess, and higher-order thinking skills developed through rich experiential learning processes [19,33].

Both experiential learning and authentic assessment are grounded in the notion that true understanding transcends mere knowledge acquisition; it involves the capacity to explore, critique, and pragmatically apply concepts in diverse contexts [3,34,35]. Experiential learning nurtures these abilities through immersive, meaningful experiences [36], while authentic assessments offer a platform for students to demonstrate their attained proficiencies [31,37].

The synergy between these approaches lies in their shared emphasis on fostering evaluative judgment and self-regulated learning. Experiential learning empowers students to reflect on their experiences, identify gaps, and iteratively refine their understanding. Authentic assessments, in turn, require students to establish criteria, analyse their performance, and take ownership of their learning journeys [31,38].

In summary, experiential learning and authentic assessment are complementary pedagogical strategies that align with the principles of constructivist learning and the goal of preparing students for the complexities of real-world challenges. Experiential learning provides the contextual experiences and reflective cycles necessary for deep learning [21,39], while authentic assessments offer a means to evaluate and validate the achieved competencies through realistic, intellectually demanding tasks, and evaluative judgement [15].

2.2. Experiential Learning Labs

This study highlights the importance of enhancing students’ active involvement in context-driven learning experiences. This regards addressing real-world global and sustainability challenges with a crisis and resilience perspective in the post-pandemic. It also emphasises the necessity for students, individually and collectively, to conduct experiential and authentic learning activities aligned with learning objectives and intended learning outcomes [27,40].

In learning terms, a challenge is interpreted in this work as a difficulty, problem, or issue that represents an obstacle or barrier to overcome in a real-world situation with an educational purpose [41]. Learning challenges might represent immersive situations in which students interact with others, for instance, concerning a community, organisation, societal, or worldwide matter. These might also refer to non-immersive situations in which students externally study a situation [42]. In this sense, relevant challenges are paramount for establishing pertinent experiences that engage students in their learning activities and obtain their recognition as contributing to their education.

Therefore, an integration of experiential learning and authentic assessment amid real-world challenges is proposed to form experiential learning labs. An experiential learning lab regards a social space of interaction in which learners, tutors, and other learning partners purposefully interact to recreate experiential-based learning activities, to achieve their intended learning outcomes [43]. This idea builds upon the notion of social labs for systemic problem-solving and decision-making activities in complex multi-stakeholder scenarios [44].

In this sense, an experiential learning lab encompasses active participation and engagement to intentionally collaborate with others towards the attainment of their intended learning outcomes or goals. Learners should purposefully work together to solve a problem, complete a task, or create a product, as they listen, discuss, and interact. Moreover, learners’ collaboration should increase their knowledge or improve their higher-order thinking skills in their activities [45]. Through collaboration in the lab, it is expected that participants enhance their interest and motivation, promoting their critical thinking, positive interdependence, individual responsibility and accountability, social skills growth, and collective feedback [46]. Accordingly, learning experiences recreated in the lab must consider a structure of roles, resources, and relations to support learners’ collective undertakings.

It is worth mentioning that a laboratory is commonly recognised as a location or physical place where learning occurs through practical hands-on work, experimentation, testing, or trials [47]. This traditional perspective mainly refers to the physical, virtual, or hybrid educational infrastructure and resources to support practical learning activities in a broad sense [48,49]. Labs might also concern facilities or open-access setups, inside or outside universities, in which students purposefully gather or situate themselves to study, individually and in groups, independently or with academic supervision. This view implies going beyond the classroom to learn by doing the actual things in real or contrived scenarios [40].

Nevertheless, there is an argument that poor learning in traditional labs may occur due to insufficient activation of the prehension capacity of learners [50]. Consequently, apart from hands-on work, lab activities should involve reflective activities to facilitate constructivist learning. This refers to the possibility of integrating experiential learning in this type of setting, resulting in increased learning relevance and authenticity [51].

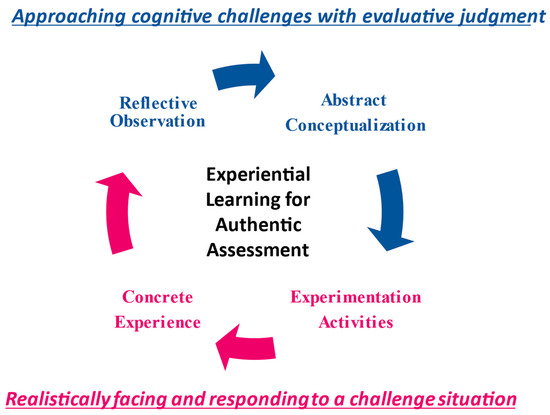

Hence, experiential learning labs here point to those places, venues, locations, or environments where reflective and practical learning activities take place regarding real-life challenging situations, inside and/or outside universities and classrooms, to achieve intended learning outcomes individually and collectively. Experiential learning labs emerge in the iterative constitution process of reflective thinking involving reflection and conceptualisation, and practical activities comprising perception and experimentation [52]. Experiential learning for authentic assessment comprises realistically facing and responding to a situation involving approaching cognitive challenges with evaluative judgment, as presented in Figure 1. Accordingly, in experiential learning labs, authentic assessment goes beyond assessment methods to consider the integration of authentic assessment principles into experiential learning activities, developing authentic experiential learning.

Figure 1.

Experiential learning for authentic assessment framework (authors’ elaboration) [15,30,31].

The building-up process of experiential learning labs considers the experiential learning cycle and authentic assessment of learning outcomes amid a contextual real-world challenge or problem situation. The conceptualisation of an experiential learning laboratory is proposed as follows:

- Learning objectives and intended outcomes in modules with a post-COVID-19 pandemic perspective such as complexity reasoning, innovative entrepreneurship, social intelligence, and citizenship commitment [53,54];

- Significant learning experiences regarding major contemporary challenges, difficulties or problem situations facing humanity in communities, society, or organisations like sustainable development, global cooperation, and technological acceleration [55];

- A structure of roles, activities, resources, and relations, which produces experiential and authentic learning experiences [52];

- Learning experience executions in terms of the deployment of teaching and learning activities designed to facilitate learning and promote the acquisition of knowledge, skills, or understanding [56];

- Assessment methods that evaluate the lab’s contribution to students’ achievements [31].

3. Methodology

This work proposes a qualitative research methodology utilising the case study approach [57]. This methodology seeks to systematically explore the intricate nuances, complexities, and distinctive attributes associated with a particular instance of an experiential learning laboratory [58,59]. This laboratory, namely the Social Lab for Sustainable Logistics (SLSL), has recently been established through collaborative efforts in Latin America and the Caribbean, aimed at facilitating active learning of SCML topics for operations management education. The case study methodology, summarised in Table 1, unfolds in six stages: defining the case, selecting the case, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, and reporting the findings [60].

Table 1.

The research methodology.

The definition of the case study involves establishing the research aim, reviewing existing literature, and addressing theoretical aspects related to experiential learning and authentic assessment, as outlined in Section 1 and Section 2. These aspects inform researchers about what aspects to investigate in practical scenarios. The selection of the case involves presenting a specific experiential learning laboratory in SCML education at the MIT SCALE Network for Latin America and the Caribbean to study its educational components. This experiential learning lab offers a platform to create SCML learning experiences that respond to the post-COVID-19 pandemic educational requirements with a crisis and resilience perspective on sustainability and global challenges.

Data were collected through various methods depending on availability and accessibility, including reviewing academic materials (i.e., syllabus, learning materials, and assignment briefs), obtaining instructors’ verbal reports (from two of the authors), and examining institutional documents (i.e., surveys). Special attention was given to accessing instructors’ perspectives to elucidate the structure of learning experiences according to the five steps presented in Section 2.2. Conversations were conducted remotely via video chats and emails with verbal consent due to geographical constraints. Overall, data were collected to describe and conceptualise the SLSL as an experiential learning lab.

Data analysis involved collating and organising data into summarised descriptions of an experiential learning lab to identify key elements according to the five steps in Section 2.2. The interpretation of data aimed to make sense of emerging issues and patterns in light of existing literature on experiential learning (i.e., learning cycle) and authentic assessment principles (see Figure 1), particularly focusing on the laboratory structure and the development of relevant learning outcomes for SCML education. Data interpretation and discussion are presented in Section 5, allowing for the identification of findings (regarding strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats), limitations, and avenues for future research.

The reporting of findings in Section 5 provides specific contextual information about the laboratory as a case study, contributing to the understanding of experiential learning laboratory conceptualisation and guiding further efforts in laboratory design and teaching practice improvement. Throughout the research process, ethical considerations were adhered to, ensuring participant privacy, confidentiality, and the protection of sensitive information.

In conclusion, the adoption of the case study methodology facilitated an in-depth exploration of the research topic within its real-life context, aiming to provide a comprehensive understanding, generate new insights, and inform practical implications within the field of study. This methodology emphasises a contextualised understanding of study situations, incorporation of multiple data sources to enhance reliability and credibility, theory-led exploration to generate new insights, and qualitative exploration of complex social situations while bridging the gap between theory and practice to maintain practical relevance.

4. Results

The SLSL serves as an experiential learning laboratory, initially established in Mexico City in 2019 and now operating within the MIT SCALE Network in Latin America and the Caribbean. It combines SCML education with sustainability challenges in urban areas and communities to achieve intended learning outcomes and research objectives in undergraduate business management and industrial engineering-related programmes.

The SLSL has offered support to various curricular and elective modules, and capstone projects spanning academic terms at different institutions in Bolivia, Colombia, and Bolivia. Originating from discussions with supply chain professionals in Mexico, the SLSL focuses on sustainability issues in supply chains, integrating insights from diverse sectors such as automotive manufacturing, parcel delivery, convenience stores, and food banks. These dialogues informed the laboratory’s learning challenges and outcomes. By aligning with Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, the SLSL provides authentic assessments through real-world connections to sustainability challenges, fostering cognitive engagement and evaluative judgment among students by developing higher-order skills.

In the context of the post-pandemic era, the SLSL offers valuable active learning opportunities, enhancing students’ understanding of global sustainability challenges and resilience within supply chains. Its practical approach encourages students to engage in experiential learning and reflect on their practices, particularly focusing on industrial engineering and business management education in urban areas of Latin America and the Caribbean.

4.1. Learning Objectives and Outcomes

The SLSL is structured to facilitate learning experiences addressing contemporary SCML issues in large urban areas, specifically focusing on their implications for sustainability. These experiences embrace a multi-stakeholder systemic perspective, encompassing environmental, social, and economic dimensions [61,62]. The primary objective of the SLSL is to cultivate students’ development of SCML disciplinary knowledge and sustainability-related competencies in related modules through active engagement in real-world activities. Such activities serve to augment students’ motivation, involvement, and the relevance of their learning experiences. The learning outcomes align with the student outcomes (A–K) specified by the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET) accreditation body, with a particular emphasis on industrial engineering programmes [63]. Consequently, the SLSL’s support is integrated into modules covering areas such as supply chain management, logistics, operations management, and systems thinking.

Additionally, the SLSL considers a learning outcome regarding the development of citizenship commitment in students. Citizenship commitment refers to the ability to create committed, sustainable, and supportive solutions to social problems and needs through strategies that strengthen democracy and the common good [54]. This learning outcome represents a crucial step forward to provide students with a post-COVID-19 pandemic perspective of resilience and responsiveness in alignment with the sustainable development agenda [62].

4.2. Significant Learning Challenges

The SLSL addresses realistic challenges through three main components: a social aspect encouraging collective engagement, an experimental array of experiences, and ongoing efforts to prototype interventions in specific contexts. These elements are guided by systemic solutions that adopt comprehensive perspectives on study situations.

The SLSL enhances learning relevance by creating immersive experiences involving participant collaboration in discussions on globally significant issues. It primarily focuses on sustainability issues in logistics and supply chain operations, aiming to restrict natural resource consumption and waste generation to acceptable levels while contributing positively to human needs satisfaction and ensuring enduring economic value for businesses. This sustainability approach encompasses environmental, social, technical, and economic dimensions, spanning present and future contexts in both proximate and distant locations [61].

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted the SLSL to shift to remote learning and collaboration. Pre-pandemic, immersive activities involved student engagement with communities to explore urban mobility, food supply, and well-being [43]. During the pandemic, remote learning focused on non-immersive challenges, such as disruptions in grocery supply chains [10]. Post-pandemic, the SLSL has engaged students in novel challenges, particularly regarding food supply dynamics, waste reduction, and the role of local businesses and supply chains in social and environmental sustainability.

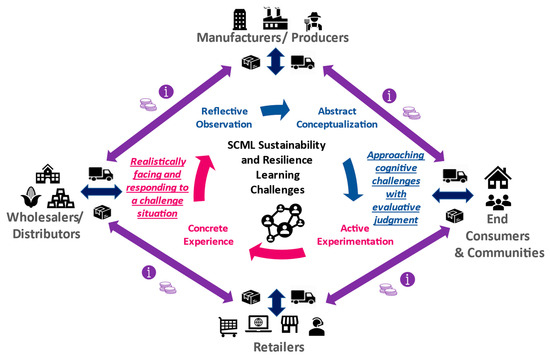

The SLSL emphasises challenges beyond technical and economic considerations, aiming to bridge the gap between disciplinary learning activities and real-world challenges in supply chains regarding issues of stakeholders’ coordination and material, information, resource, and product flows. It provides a platform for students to realistically engage with SCML situations, employing evaluative judgment in cognitive challenges, as presented in Figure 2, for instance, developing ABET student outcomes such as “an ability to apply engineering design to produce solutions that meet specified needs with consideration of public health, safety, and welfare, as well as global, cultural, social, environmental, and economic factors” [63].

Figure 2.

The Social Lab for Sustainable Logistics Framework for Experiential Learning and Authentic Assessment (authors’ elaboration) [15,30,31,43].

Within the SLSL framework, problem-solving applications are explored in domains including last-mile logistics, retail operations, and urban freight transportation, with a pronounced emphasis on experiential learning addressing food security, environmental conservation, energy efficiency, public health, social equity, and inclusion. All these challenges match the sustainability development goals (SDGs), especially SDGs #2 Zero Hunger, #4 Quality Education, #11 Sustainable Cities and Communities, #12 Responsible Consumption and Production, and #17 Partnerships for the Goals [62].

4.3. The SLSL Structure

The SLSL systematically addresses challenges for problem-solving, aimed at achieving intended learning outcomes, by establishing a structured framework encompassing roles, learning activities, resources, and participant relations. The lab involves stakeholders such as students, mentors, instructors, evaluators, and educational partners, collaborating within distinct learning experiences. These lab dynamics encapsulate the social dimension of the SLSL, wherein participants collectively and purposefully engage with a clear educational objective.

The SLSL employs a working framework to conceptualise stakeholder engagement in supply chain and logistics activities, identifying key stakeholders, material and information flows, and their impact on value delivery, performance outcomes, and sustainability concerns (see Figure 2). This comprehensive framework guides participants, as a conversational tool, in identifying, interacting, reflecting, and acting on relevant issues, facilitating a holistic understanding of supply chain dynamics within the context of sustainability. Summing up, these sustainability SCML challenges provide realistic study situations, from an authentic assessment perspective, with complex and open-ended tasks reflecting the ambiguities and intellectual nuances found in the real world.

4.4. Learning Experience Execution

Table 2 offers an overview of a learning experience instance conducted by the SLSL during the post-pandemic period. This experience focused on addressing solid waste generation in retail operations within an operations management module for industrial engineering at a Mexican university, in collaboration with researchers of the MIT SCALE Network for Latin America and the Caribbean. Pedagogically, the module aimed to reengage students, from different engineering programmes, in on-campus activities post-COVID-19 pandemic and emphasise the practical value of the course for their studies and future professional practice. Consequently, a significant shift occurred in course delivery in 2022, aligning operations management with circular economy and sustainability challenges from an experiential learning perspective.

Table 2.

Experiential learning activities for authentic assessment.

The module explored various problem situations related to SCML operations in a wine and spirits distribution company, utilising concepts and tools such as process mapping, production planning, supply chain management, inventory management, and quality improvement to address issues of flexibility, dependability, speed, quality, and cost.

Students were tasked with examining the root causes of food and solid waste generation from a circular economy perspective [64]. This involved proposing alternative solutions to minimise economic loss and exploring reuse opportunities for expired products in some retail points. Additionally, students evaluated the impact of waste generated from packaging materials, assessing economic and environmental factors, and proposing innovative operational changes aligned with circular economy principles.

Through data collection, observation, and interviews at retail points, students identified improvement actions and proposed operational changes based on circular economy concepts. Table 2 summarises the educational components of the SLSL’s learning experience, aligning with the four stages of the experiential learning cycle and the three principles of authentic assessment.

Incorporating sustainability and circular economy principles into experiential learning design and authentic assessment yielded several outcomes:

- Nurturing higher-order skills through realistic and intellectually demanding tasks for SCML problem-solving and decision-making in authentic assessment activities;

- A novel integration of circular economy themes with specific disciplinary content, surpassing previous course design and literature, led instructors to identify practical connections between theoretical concepts and teaching methods, through problem-solving and decision-making activities, aligning them with sustainability principles;

- Expansion of learning activities beyond the disciplinary course scope, fostering students’ understanding of their personal and professional responsibilities and responsive actions towards community sustainability;

- Implementation of learning activities emphasising transdisciplinary sustainability education within a global agenda;

- Promotion of collaboration and teamwork in multidisciplinary settings;

- Integration of course activities with local businesses as educational partners, facilitating real-world case-study-based education.

4.5. Assessment Methods

The primary elements to assess the lab’s educational contribution are threefold (see Table 3). First, the lab considers modules’ methods of assessment such as ABET student outcomes attainment, exams, journals, portfolio reports, and presentations to provide evidence of students’ learning achievements. Second, it considers learning opinion surveys regarding learning outcome development and student interest, motivation, and learning relevance regarding the learning experience and challenge. Third, the lab considers student feedback surveys in modules to assess, for instance, module applicability, pedagogical effectiveness, and academic support.

Table 3.

Lab’s impact assessment.

Data collection can involve the voluntary participation of all students in the learning activities and surveys, ensuring equal accessibility and opportunity for participation without sampling or random selection. Survey responses might be anonymised, preventing linkage between individual students, learning outcomes, and survey opinions, thus reflecting each student’s unique experience without comparability to other contexts. Furthermore, descriptive (or other types of) statistical analysis can be carried out to describe the results’ distribution and contrast results between other experiences or instances.

Referring to the specific learning experience previously described concerning circular economy improvements, the specific students’ assessment reports, survey results, and marks are out of the scope of this work. These have been reported elsewhere to assess students’ learning achievement and feedback [65].

Nevertheless, students’ work demonstrated a very good understanding and ability to address circular economy issues in retail and warehousing operations as indicated in their student outcomes (i.e., ability to apply engineering design to produce solutions), group work reports, and presentations, contributing to overall learning outcomes and skills development for operations management. That is, students successfully explored solid waste issues in real practice, integrating a real-world circular economy challenge, operations management learning content, and problem-solving processes. Accordingly, these (authentic assessment) activities require students to establish evaluative criteria, analyse their progress, and self-direct their learning journeys to produce their expected learning outcomes.

Finally, the learning experience illustrated translating real-world situations into immersive learning activities, applying the experiential learning cycle and authentic assessment principles to adapt activities linked to circular economy issues. The student feedback survey responses shed light on opportunities to enhance the course by establishing stronger connections between the content and professional contexts. Students appreciated that the module learning content was presented in a manner that illustrates its practical applications and relevance to their future careers. Additionally, the feedback highlighted that an interactive and participatory learning environment, where students could actively engage in discussions and share their perspectives, facilitated a more conducive atmosphere for learning. By encouraging open dialogue and the free exchange of ideas during class sessions, students felt more invested in the learning process and better able to grasp and internalise the course concepts.

Overall, this experience highlights how undergraduate students can extend learning beyond the classroom, enhancing application cases for operations management education. Therefore, the SLSL turned out helpful in hosting a learning experience involving experiential learning for authentic assessment.

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings

This study examined the outcomes of developing an experiential learning lab for SCML education with a post-COVID-19 pandemic perspective. This allowed us to illustrate the lab’s composition elements to provide experiential learning under the principles of authentic assessment. The lab implementation through the case study revealed strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats amid a learning experience.

- Strengths:

- The development of experiential learning labs as an educational platform to articulate experiential learning and authentic assessment that provide students with active learning experiences with a post-pandemic perspective of crisis and resilience on global challenges and sustainability;

- An experiential learning lab allows for grounding reflective thinking into practical undertakings amid real-world challenges. This is about realistically facing and responding to challenging situations while approaching cognitive challenges with evaluative judgment;

- Real-world challenges can be connected to disciplinary and transdisciplinary learning objectives and intended learning outcomes to enhance learning relevance and student engagement, enriching disciplinary and professional practice;

- An experiential learning lab offers authentic learning experiences that promote problem-solving and decision-making undertakings through individual and collective action and inquiry, developing higher-order skills;

- An experiential learning lab enables students to act as knowledge producers, creating meaningful contextualised solutions and action plans;

- The lab involves the development of post-COVID-19 pandemic crisis and resilience-related learning outcomes concerning sustainability and global challenges;

- An experiential learning lab articulates a space for pedagogical innovation and disciplinary research in which participants can improve their teaching and learning practices while investigating relevant topics;

- An experiential learning lab has provided a platform for local and international collaboration, present and virtual, concerning pedagogical and disciplinary research.

- Weaknesses:

- The process of conceptualising, organising, and deploying the lab’s activities is time-consuming and requires a great effort to overcome bureaucratic administration barriers, involving, for instance, changes to syllabus and assessment methods. This might turn out discouraging and frustrating for academics to undertake an initiative like this;

- The assessment of student learning impact and learning outcomes development is still limited and requires further investigation. Although favourable results in surveys and grades have been obtained in previous learning experiences, a precise evaluation and analysis of the lab’s contribution requires further implementations and assessments;

- Academic regulations and ethical approvals might impinge on the immersion of students in real-world settings, making it difficult to implement learning experiences.

- Opportunities:

- The development of other types of experiential learning labs beyond SCML education, involving, for instance, other engineering and management disciplines;

- The exploration of other sustainability-related challenges for SCML education, such as gas emissions, food safety, traffic congestion, and energy consumption, among others;

- The development of further links with communities to build education partnerships and collaborations to enhance their resilience and sustainability in HE;

- Rolling out experiential learning labs for resilience and sustainability education in future pedagogical developments as an option for experiential learning and authentic assessment in HE in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era;

- A definition of intended learning outcomes and higher-order skills to develop in experiential learning labs amid different challenges, themes, or disciplines;

- The development (and measurement) of diverse learning outcomes and their impact on learners across disciplines, using instructional designs that integrate experiential learning activities and authentic assessment methods under a constructive alignment.

- Threats:

- Reaching the lab’s stability within the MIT SCALE Network for Latin America and the Caribbean as a reduced number of academics are currently collaborating on this topic;

- The limited number of new learning experiences across different universities in Latin America and the Caribbean region, involving diverse academic programmes and real-world situations that impinge on the lab concept development.

In summary, the experiential learning laboratory has exemplified the potential for associating contemporary, pertinent global challenges with experiential and authentic learning encounters, under predefined learning objectives and intended educational outcomes. The presented case study delineates the capacity to translate authentic scenarios into immersive learning exercises conducive to problem-solving and decision-making within real-world contexts. Moreover, it elucidates meaningful learning engagements influenced by a post-COVID-19 pandemic perspective, emphasising interactivity, engagement, and resilience.

Furthermore, in the context of students’ engagement with circular operations management, the findings indicate their adept exploration of solid waste concerns within practical domains. This educational encounter facilitated the integration of a tangible circular economy challenge with operations management education, fostering a pragmatic problem-solving approach. Consequently, students engaged in an experiential learning process, enriching their personal development while benefiting the educational institution. This pedagogical endeavour also underscores the capacity of undergraduate students to transcend conventional classroom boundaries, thereby broadening the scope of application scenarios within operations management education.

5.2. Limitations

Limitations are evident within this study concerning various aspects of the experiential learning laboratory. Primarily, a limitation arises regarding the conception of experiential learning itself. While acknowledged as a prevalent pedagogical approach, alternative methodologies for instructional design and learning comprehension exist. Despite its recognition, further implementation within the discipline is warranted, given the lack of comparative research. Potential alternatives such as challenge-based learning, inquiry-based learning, or problem-based learning could serve as foundational frameworks for future endeavours.

Another limitation pertains to the methodological framework employed herein. The utilisation of a single case study inherently restricts the generalisability and external validity of research findings, offering insights specific to the examined instance within the experiential learning laboratory. Consequently, while informative for carrying analogous initiatives, caution is warranted in extrapolating broader conclusions.

Additionally, this work did not carry out an assessment and analysis of the SLSL’s impact on students’ learning and learning outcome development. The case study focused on describing and characterising the lab and illustrating a learning experience. The impact assessment and analysis have been considered for future work.

Other limitations manifest in the context of the proposed data collection methods, particularly concerning the utilisation of survey instruments to assess learning experiences. Given the subjective nature of survey responses, influenced by individual perspectives and biases, the potential for misrepresentation exists. However, the integration of learning experience surveys with course feedback mechanisms and student achievements offers a means of validation. Moreover, the effectiveness of statistical analysis and interpretation in a learning experience may be hindered by low response rates among participating students, limiting understanding. A validation of these instruments is also considered for future work.

Furthermore, deficiencies are apparent in the assessment and evaluation instruments tailored to appraise learning experiences and the laboratory’s impact. Thus, there is a pressing need within the lab framework for the development of specialised tools to facilitate comprehensive data collection of student learning efficacy, satisfaction, engagement, and course endorsement.

5.3. Future Work

Additional implementations of novel instances of experiential learning laboratories and learning experiences are imperative to enhance understanding of their impact and contribution to learning efficacy, skill development, and learning outcomes. Moreover, future undertakings should prioritise the creation of fresh instances addressing contemporary challenges, such as the advent of new technologies, climate change, food security, ending poverty, or healthcare provision, thereby fostering novel learning experiences from a post-COVID-19 pandemic view.

Moreover, despite the prominence of experiential learning and authentic assessment before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, more case studies showcasing their combined use could advance teaching practices, foster interdisciplinary collaboration among instructional designers, and reveal new possibilities and impacts. Thus, instructional design can be pivotal in crafting innovative learning experiences that align with contemporary developments and educational needs. Furthermore, addressing the limitations inherent in the research methodology necessitates an enhancement of data collection methods and analytical instruments to accommodate potential new study variables, thereby augmenting research reliability, transferability, and validity.

Lastly, the adoption of alternative pedagogical approaches, such as inquiry-based learning, problem-based learning, or challenge-based learning, is advocated to exemplify active and authentic assessment principles.

6. Conclusions

The post-COVID-19 pandemic era offers an opportunity to cultivate learning experiences within HE that engage with contemporary global and sustainability challenges through a lens of crisis and resilience. These challenges can be structured as educational scenarios aligned with predetermined learning objectives and outcomes, facilitating the development of higher cognitive skills and disciplinary knowledge among students.

This study delineates the role of an experiential learning laboratory in advancing operations management education by facilitating the creation of learning experiences that embody principles of experiential learning and authentic assessment. An experiential learning laboratory serves as a platform where students confront realistic challenges, fostering problem-solving and decision-making abilities through reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. Consequently, such laboratories become first-hand opportunities for business and management but also engineering programmes to enable students to cultivate contextually relevant learning experiences that enhance their engagement and involvement.

The principal contribution of this study lies in providing the conceptualisation of experiential learning labs with a post-COVID-19 pandemic perspective to develop crisis- and resilience-related learning outcomes. The contribution also involves a framework underpinning the labs’ rationale that integrates Kolb’s experiential learning cycle with principles of authentic assessment. This framework can help enable students to effectively address and navigate cognitive challenges while exercising evaluative judgment. To exemplify experiential learning labs and the framework, a case study is presented involving a circular economy learning experience within an operations management module, aimed at augmenting student engagement and participation in the post-pandemic. The primary objective was to cultivate highly pertinent learning experiences, a citizenship commitment learning outcome, and an appreciation for sustainable development within SCML education.

However, further research is needed to ascertain the efficacy of such experiential learning laboratories in enriching students’ learning, participation, and engagement. Moreover, other types of experiential learning should be developed in other disciplines as well as addressing different challenges with a post-pandemic view. Consequently, additional case studies must be developed to validate and refine the propositions and assertions concerning these laboratories.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.E.S.-N. and A.C.D.S.-O.; methodology, D.E.S.-N.; validation, A.C.D.S.-O.; formal analysis, D.E.S.-N. and A.C.D.S.-O.; investigation, D.E.S.-N. and A.C.D.S.-O.; resources, D.E.S.-N.; data curation, D.E.S.-N. and A.C.D.S.-O.; writing—original draft preparation, D.E.S.-N. and A.C.D.S.-O.; writing—review and editing, D.E.S.-N., A.C.D.S.-O. and J.A.P.-M.; visualization, D.E.S.-N., A.C.D.S.-O. and J.A.P.-M.; supervision, D.E.S.-N.; project administration, D.E.S.-N. and J.A.P.-M.; funding acquisition, J.A.P.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Writing Lab, Institute for the Future of Education, Tecnologico de Monterrey, Mexico.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the review board deeming it “Research without risk,” i.e., studies using retrospective documentary research techniques and methods, as well as those that do not involve any intervention or intended modification of physiological, psychological, and social variables of study participants, among which the following are considered: questionnaires, interviews, review of clinical records, and others, in which they are not identified or sensitive aspects of their behaviour are not addressed.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (D.E.S.-N).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Zhao, Y.; Watterston, J. The Changes We Need: Education Post COVID-19. J Educ Chang. 2021, 22, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aji, C.A.; Khan, M.J. The Impact of Active Learning on Students’ Academic Performance. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 07, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.H. Experiential Learning—A Systematic Review and Revision of Kolb’s Model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 1064–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Horta, H.; Postiglione, G.A. Living in Uncertainty: The COVID-19 Pandemic and Higher Education in Hong Kong. Stud. High. Educ. 2021, 46, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassudov, L.; Korunets, A. COVID-19 Pandemic Challenges for Engineering Education. In Proceedings of the 2020 XI International Conference on Electrical Power Drive Systems (ICEPDS), Saint Petersburg, Russia, 4 October 2020; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Vieyra Molina, A.; Belden, M.; se la Calle, J.R.; Martinezparente, A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Higher Education in Mexico, Colombia and Peru. 2020. Available online: https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/es_mx/topics/covid-19/ey-parthenon-educacion.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Burki, T.K. COVID-19: Consequences for Higher Education. Lancet 2021, 21, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, K.H. Impact of COVID-19 on Higher Education: Critical Reflections. High Educ Policy 2022, 35, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.; Karakaya, K.; Turk, M.; Karakaya, Ö.; Castellanos-Reyes, D. The Impact of COVID-19 on Education: A Meta-Narrative Review. TechTrends 2022, 66, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Alanis-Uribe, A.; da Silva-Ovando, A.C. Learning Experiences about Food Supply Chains Disruptions over the Covid-19 Pandemic in Metropolis of Latin America. In Proceedings of the 2021 IISE Annual Conference, Online, 22–25 May 2021; Ghate, A., Krishnaiyer, K., Paynabar, K., Eds.; pp. 495–500. [Google Scholar]

- Fenech, R.; Baguant, P.; Alpenidze, O. Academic Emergent Strategies and Experiential Learning Cycles in Times of Crisis. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pultoo, A.; Oojorah, A. Designing Remote Education in a VUCA World. IJCT 2020, 20, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Refae, G.A.; Kaba, A.; Eletter, S. Distance Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic: Satisfaction, Opportunities and Challenges as Perceived by Faculty Members and Students. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2021, 18, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code, J.; Ralph, R.; Forde, K. Pandemic Designs for the Future: Perspectives of Technology Education Teachers during COVID-19. Inf. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel, V.; Boud, D.; Bloxham, S.; Bruna, D.; Bruna, C. Using Principles of Authentic Assessment to Redesign Written Examinations and Tests. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2019, 57, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winstone, N.E.; Boud, D. Universities Should Learn from Assessment Methods Used During the Pandemic—And Cut Down on Exams for Good. The Conversation. 11 August 2020. Available online: https://theconversation.com/universities-should-learn-from-assessment-methods-used-during-the-pandemic-and-cut-down-on-exams-for-good-143374 (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Ratten, V. The Post COVID-19 Pandemic Era: Changes in Teaching and Learning Methods for Management Educators. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikova, A. Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Russ. Lang. J. 2021, 71, 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, A.; Zarama, R. The Process of Embodying Distinctions—A Re-Construction of the Process of Learning. Cybern. Hum. Knowing 1998, 5, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, S.K. Innovative Experiential Learning Experience: Pedagogical Adopting Kolb’s Learning Cycle at Higher Education in Hong Kong. Cogent Educ. 2019, 6, 1644720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y. The Role of Experiential Learning on Students’ Motivation and Classroom Engagement. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 771272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, D.D.; McCarty, D.L.; Brown, C.L. Experiential Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Reflective Process. J. Constr. Psychol. 2020, 34, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, A.; Kolb, D. Eight Important Things to Know about The Experiential Learning Cycle. Aust. Educ. Lead. 2018, 40, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins, G. The Case for Authentic Assessment. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 1990, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel, V.; Bloxham, S.; Bruna, D.; Bruna, C.; Herrera-Seda, C. Authentic Assessment: Creating a Blueprint for Course Design. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 840–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Da Silva-Ovando, A.C.; Mejía-Argueta, C.; Chong, M. Reflexiones Desde La Práctica Docente: Experiencias de Aprendizaje Para La Educación En Ingeniería Industrial En La Pospandemia. Apunt. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2022, 49, 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J.B.; Tang, C.S. Teaching for Quality Learning at University: What the Student Does, 4th ed.; SRHE and Open University Press Imprint; McGraw-Hill, Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-335-24275-7. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO International Bureau of Education. Glossary of Curriculum Terminology; UNESCO International Bureau of Education: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Benkert, C.; van Dam, N. Experiential Learning: What’s Missing in Most Change Programs. Operations. 2015. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/experiential-learning-whats-missing-in-most-change-programs (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Kolb, D.A.; Fry, R. Towards an Applied Theory of Experiential_Learning. In Theories of Group Process; Cooper, C., Ed.; John Wiley: London, UK, 1975; pp. 33–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins, G. A True Test: Toward More Authentic and Equitable Assessment. Phi Delta Kappan 2011, 92, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.H. Authentic Assessment. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-0-19-026409-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lalley, J.P.; Miller, R.H. The Learning Pyramid: Does It Point Teachers in the Right Direction? Education 2007, 128, 64–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bergsteiner, H.; Avery, G.C. The Twin-Cycle Experiential Learning Model: Reconceptualising Kolb’s Theory. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2014, 36, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, D.; Pavlica, K.; Thorpe, R. Rethinking Kolb’s Theory of Experiential Learning in Management Education: The Contribution of Social Constructionism and Activity Theory. Manag. Learn. 1997, 28, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradberry, L.A.; De Maio, J. Learning By Doing: The Long-Term Impact of Experiential Learning Programs on Student Success. J. Political Sci. Educ. 2019, 15, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picault, J. Don’t Just Read the News, Write the News!—A Course about Writing Economics for the Media. J. Econ. Educ. 2021, 52, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrett, C.G.; Adams, J.; Johnson, A.W.; Swenson, J.E.S. Collaborating with Aviation Museums to Enhance Authentic Assessments for Aerospace Structures. ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference Proceedings. 2023. Available online: https://nemo.asee.org/public/conferences/327/papers/38585/view (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Vince, R. Reflections on “Behind and Beyond Kolb’s Learning Cycle”. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 46, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.K.; Connors, P.; Donnelly-Hermosillo, D.; Full, R.; Hove, A.; Lanier, H.; Lent, D.; Nation, J.; Tucker, K.P.; Ward, J.; et al. Biology Beyond the Classroom: Experiential Learning Through Authentic Research, Design, and Community Engagement. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2021, 61, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford English Dictionary. Challenge, n., Sense 6.b. Available online: https://www.oed.com/dictionary/challenge_n?tl=true (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Garay-Rondero, C.L. Work in Progress: Transforming Laboratory Learning Experiences for Industrial Engineering Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE World Engineering Education Conference (EDUNINE), Ibero-America, Santos, Brazil, 13–16 March 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Rodríguez Calvo, E.Z. Social Lab for Sustainable Logistics: Developing Learning Outcomes in Engineering Education. In Operations Management for Social Good; Leiras, A., González-Calderón, C.A., de Brito Junior, I., Villa, S., Yoshizaki, H.T.Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1065–1074. ISBN 978-3-030-23815-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Z. The Social Labs Revolution: A New Approach to Solving Our Most Complex Challenges, 1st ed.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-62656-073-4. [Google Scholar]

- Major, C. Collaborative Learning: A Tried and True Active Learning Method for the College Classroom. New Drctns Teach Learn 2022, 2022, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laal, M.; Laal, M. Collaborative Learning: What Is It? Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 31, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, E.; Paukovics, E.; Cheniti-Belcadhi, L.; El Khayat, G.; Said, B.; Korbaa, O. What Do You Mean by Learning Lab? Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 4501–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alstete, J.W.; Beutell, N.J. Designing Learning Spaces for Management Education: A Mixed Methods Research Approach. J. Manag. Dev. 2018, 37, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.B.; Lippincott, J.K. Learning Spaces More than Meets the Eye. Educ. Q. 2003, 289, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulwahed, M.; Nagy, Z.K. Applying Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle for Laboratory Education. J Eng. Edu 2009, 98, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, A.; Lukarov, V.; Romagnoli, G.; Uckelmann, D.; Schroeder, U. Experiential Learning in Labs and Multimodal Learning Analytics. In Adoption of Data Analytics in Higher Education Learning and Teaching; Ifenthaler, D., Gibson, D., Eds.; Advances in Analytics for Learning and Teaching; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 349–373. ISBN 978-3-030-47391-4. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Calvo, E.Z.R.; Rondero, C.L.G. Expanding the Concept of Learning Spaces for Industrial Engineering Education. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 8–11 April 2019; pp. 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberg, M.; Torgersen, G.-E. Resilience Competence Face Framework for the Unforeseen: Relations, Emotions and Cognition. A Qualitative Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 669904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecnologico de Monterrey. Competencias Transversales; Tecnologico de Monterrey: Monterrey, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Colomina, C. The World in 2024: Ten Issues That Will Shape the International Agenda. NotesInt 2023, 299, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbiss, J. Students’ Learning Experiences: What Do We Mean and What Can We Know? In Understanding Teaching and Learning; Kaur, B., Ed.; SensePublishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 67–78. ISBN 978-94-6091-864-3. [Google Scholar]

- Tharenou, P.; Donohue, R.; Cooper, B. Case Study Research Designs. In Management Research Methods; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, K.F. Recognising Deductive Processes in Qualitative Research. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2000, 3, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Applied Social Research Methods; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4129-6099-1. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The Case Study Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Reprint; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-1-84112-084-3. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ABET. 2022–2023 Criteria for Accrediting Engineering Programs. Available online: https://www.abet.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2022-23-EAC-Criteria.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy Vol. 1: An Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Arias-Portela, C.Y.; González De La Cruz, J.R.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E. Experiential Learning for Circular Operations Management in Higher Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).