Professional Learning Communities of Student Teachers in Internship

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research on Student-Teacher PLCs

1.2. Research Areas and Findings Regarding ST-PLCs

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context and Participants

2.2. Intervention

- Centerpiece “ST-PLC”: The center symbolizes the ST-PLC. The student teachers’ PLC forms the basis for the success of the ST-PLC work. Students are provided with foundational knowledge of the PLC concept.

- Dimensions of the PLC process: The six dimensions “Identify”, “Analyze”, “Plan”, “Reflect”, “Practice”, and “Evaluate” build on each other in terms of content but are also considered to be a closed cycle. The basic ST-PLC work takes place within the framework of these six dimensions. After identifying a problem or a topic that is considered by the students to be focal point for their pedagogical studies, the next step—“Analyze”—takes place. This step is used for an in-depth examination of the previously identified problems or topics with the aim of developing operational goals and adequate measures, which are then set out in a clearly structured action plan [36]. This serves as the basis for targeted, further professional development and is fulfilled in the step “Plan”. One goal is to achieve a critical-reflective attitude and to deal with issues in greater depth. Therefore, a (critical) examination of the measures takes place in the fourth dimension, “Reflect”. The measures set in the action plan are then implemented in practice in schools (“Practice”). In the sixth dimension, “Evaluate”, the overall process is subjected to critical evaluation and reflection. The goals that were set are examined to ascertain whether and to what extent they have been achieved. Indicators for this are the defined measures in the action plan. If the objectives are successfully achieved, the process begins anew with the identification of topics, the setting of targets, and corresponding measures. If the realization of the goals is less successful, the previous measures are revised or new measures are taken and documented in the action plan.

- The reflection level “Reflection-IN-Action” illustrates the importance of holistic reflection on the entire process.

- It is also important to place reflection at the meta-level, which is the aim of “Reflection-ON-Action”. In particular, it is intended to be a meta-analysis of the functioning of the group, its structures and processes, and the effectiveness of the ST-PLC work as a whole.

2.3. Aims of the Study and Research Question

- The basic possibility of establishing and implementing an ST-PLC within the framework of teacher-training studies;

- Acceptance of ST-PLCs by students;

- Effectiveness of ST-PLCs regarding the acquisition of competencies, especially in courses with pedagogical and practical components;

- Acquisition of competencies regarding personal professional development;

- Perspectives regarding acceptance and use of PLCs in future professional life;

- Development of a reflective attitude.

2.4. Research Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Data

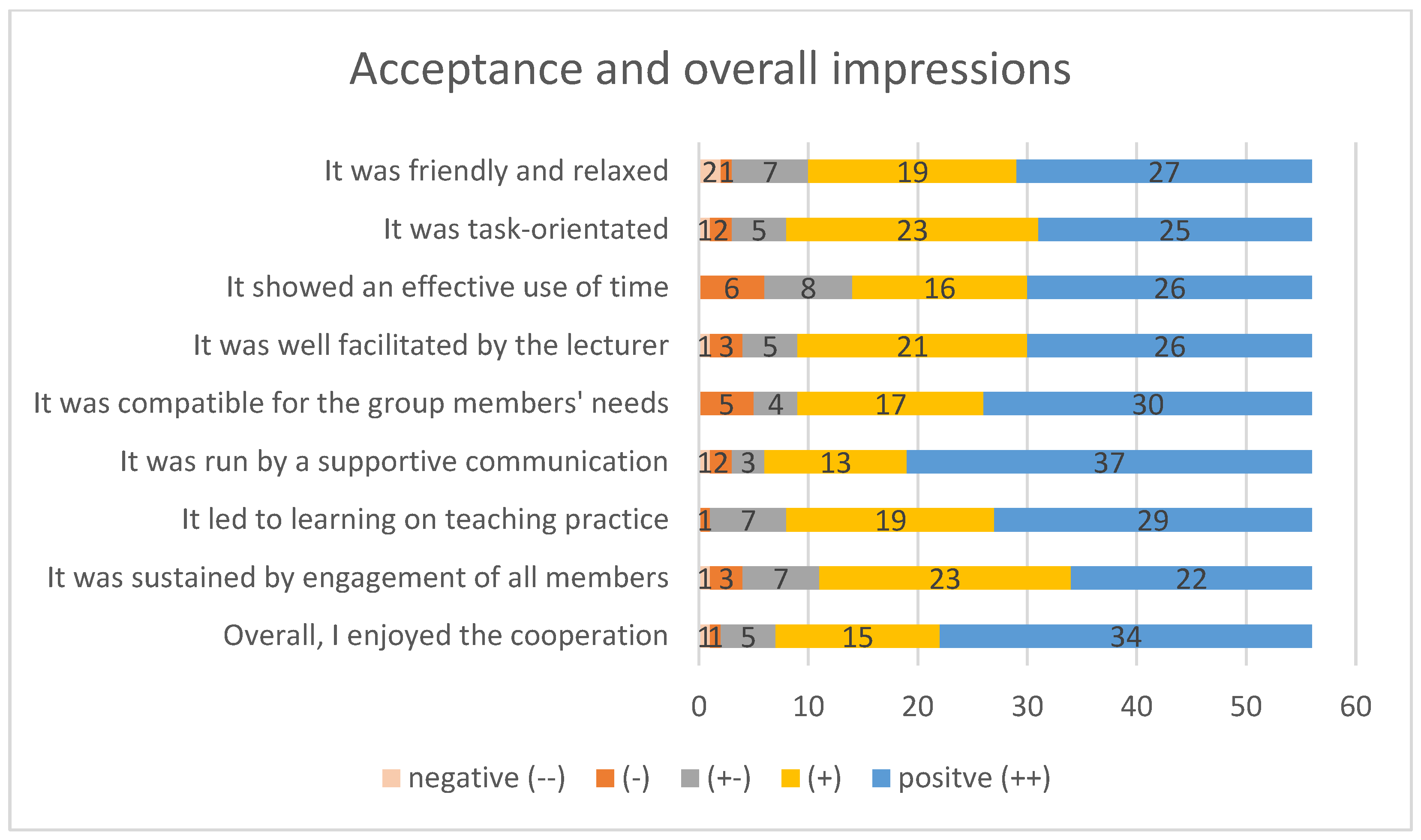

3.1.1. Acceptance and Overall Impressions of ST-PLCs

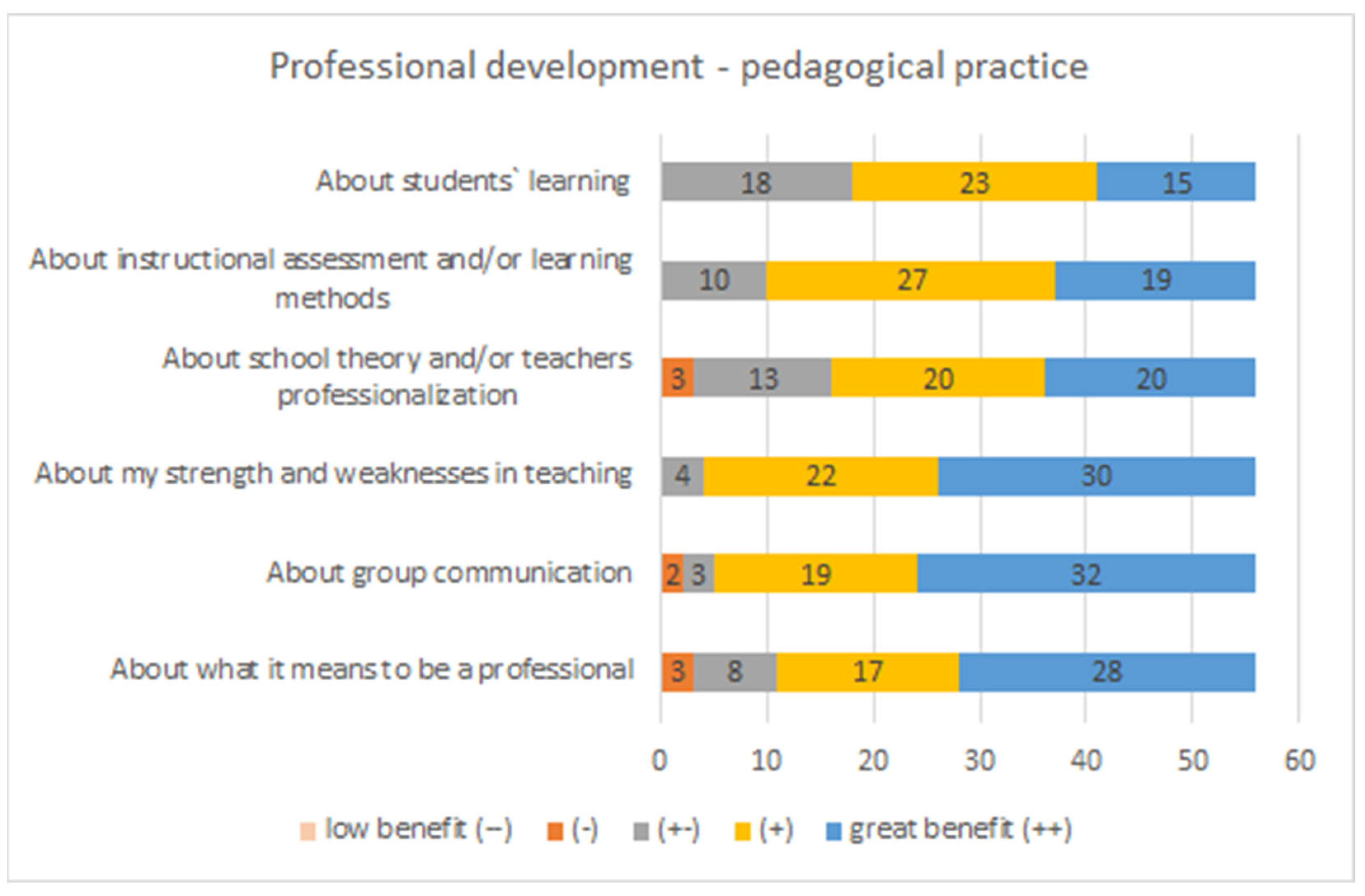

3.1.2. Professional Development Related to Pedagogical Practice

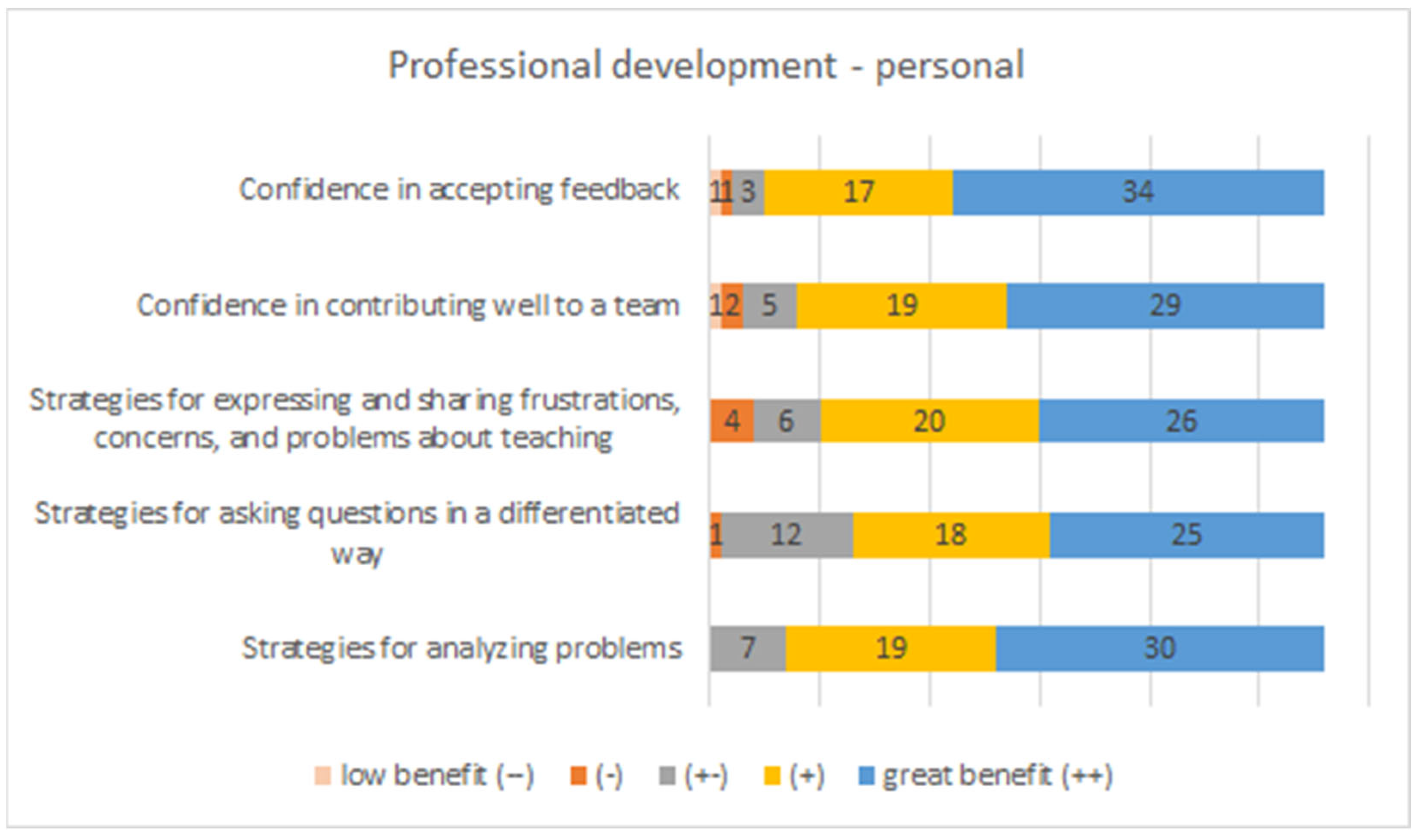

3.1.3. Professional Development Related to Personal Gains

3.1.4. Impact on Future Work as a Teacher

3.2. Qualitative Data

- Impact on practical pedagogical knowledge

[…] we began to exchange points of view and different perspectives on teaching activities. Gradually, we used these [PLC] sessions to share our problems and to propose solutions, discussing and cooperating to help us improve our teaching. More and more ideas were offered so that each one of us could improve in aspects that present us with the greatest challenge. (Ana (Names are pseudonyms))

This has been the case with classroom management. By participating in a PLC, I have learnt strategies I did not know or thought of. In this respect, working collaboratively has the benefit of facilitating the introduction of new innovations in our practice while feeling supported and accompanied by the PLC members. (Cristina)

- Impact on reflective and analytical skills

The PLC meetings have helped me to better see what my strengths and weaknesses are, as well as my progress during over weeks, by analyzing it and sharing results, and receiving the opinion or feedback of the colleagues in order to always continue improving. (Sonia)

[…] participating in a PLC has been an exceptional help in the analysis of the principles underlying practice, discussing them with the rest of the group and visualizing new forms of action. (Soledad)

- Impact on self-confidence

[…] through the PLC I feel that I have more confidence in myself as a teacher, because I have been able to learn and improve, leaving aside the shame of sharing and that of being observed from the perspective of others. (Cristina)

In my experience, a PLC is constantly trying out new strategies to improve student learning, so people within the team must feel free to innovate. Teachers can never know what teaching works best for their students unless they are given the freedom to try out new strategies. PLCs can make this happen by having teachers collect evidence and use data and protocols to determine which strategies were most effective. (Luisa)

- Impact on the view of teacher collaboration

Being a teacher requires collaboration between the members of a school, sharing, reflecting and seeking to promote improved educational practice. So, I think these meetings have brought me closer to the reality of education. (Julia)

On the other hand, if this educational school followed a PLC approach, that is, if the school was conceived as a large PLC as defined above, the interpersonal relationships at the school would benefit, and relationships of trust and professional development could be established. (Cristina)

- Impact on emotional wellbeing

Thanks to the PLC work, I have been able to connect with classmates that experience situations that are similar to mine, help, support and listen to each other. This has not only allowed us to ‘let off steam’ sometimes, but it has also served as therapy in which we could find ideas to solve those things that made us drown in a glass of water. (Pilar)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Christensen, A.A. A global measure of professional learning communities. Profess. Dev. Educ. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairon, S.; Goh, J.W.P.; Chua, C.S.K.; Wang, L.Y. A research agenda for professional learning communities: Moving forward. Profess. Dev. Educ. 2017, 43, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsen, M. Professionelle Lerngemeinschaften in der Schule. In Schulentwicklung und Schulwirksamkeit; Holtappels, H.G., Höhmann, K., Eds.; Beltz Juventa: München, Germany, 2005; pp. 180–195. [Google Scholar]

- Buhren, C.; Rolff, H.-G. Handbuch Schulentwicklung und Schulentwicklungsberatung, 2nd ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vescio, V.; Adams, A. Learning in a professional learning community: The challenge evolves. In The SAGE Handbook of Learning; Scott, D., Hargraves, E., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 274–284. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenholtz, S. Teachers’ Workplace: The Social Organization of Schools; Longman: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.; Cambron-McCabe, N.; Lucas, T.; Smith, B.; Dutton, J.; Kleiner, A. Schools That Learn. A Fifth Discipline Fieldbook for Educators, Parents, and Everyone Who Cares about Education; Crown Business: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rolff, H.-G. Handbuch Unterrichtsentwicklung; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsen, M.; Rolff, H.-G. Professionelle Lerngemeinschaften von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern. Z. Pädagogik 2006, 52, 167–184. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, S.; Hader-Popp, S. Von Kollegen lernen: Professionelle Lerngemeinschaften. In Praxis Wissen Schulleitung; Bartz, A., Fabian, J., Huber, S.G., Kloft, C., Rosenbusch, H., Sassenscheidt, H., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer: München, Germany, 2005; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Timperley, H.; Wilson, A.; Barrar, H.; Fung, I. Teacher Professional Learning and Development; Educational Practices Series 18; UNESCO International Bureau of Education: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; Available online: http://www.iaoed.org/downloads/EdPractices_18.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Kansteiner, K.; Stamann, C.; Buhren, C.; Theurl, P. Professionelle Lerngemeinschaften als Entwicklungsinstrument im Bildungswesen; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios, E.; Sanchidrián, C.; Carretero, A. Comunidades Profesionales de Aprendizaje en la formación práctica inicial de profesorado: La perspectiva del alumnado. In Proceedings of the Actas del VII Congreso de Innovación Educativa y Docencia en Red (In-Red 2021), Valencia, Spain, 13–15 July 2021; pp. 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchidrián, C.; Barrios, E.; Theurl, P. Professional Learning Communities for Student Teachers: Possibilities according to the Erasmus+ TePinTeach Project. In Proceedings of the Actas del XVII Congreso Nacional y IX Iberoamericano de Pedagogía, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 7–9 July 2021; pp. 783–789. Available online: https://www.usc.gal/libros/module/xeprotected/open?productId=1017&action=download (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Theurl, P.; Barrios, E.; Frick, E.; Sanchidrián, C. Professional learning communities of student teachers in internship. In Proceedings of the 20th Biennial EARLI-Conference, Thessaloniki, Greece, 22–26 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kansteiner, K.; Barrios, E.; Skoulia, T.; Theurl, P.; Emstad, A.B.; Louca, L.; Sanchidrian, C.; Schmid, S.; Knutsen, B.; Frick, E.; et al. TePinTeach–Evaluation Report. 2022. Available online: http://www.tepinteach.eu/deliverables/#IO5---Evaluation-Report:-Evaluation-of-the-chances-of-the-student-teacher-PLCs-and-student-teachers-%E2%80%93-mentors-PLCs (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Rigelman, N.M.; Ruben, B. Creating foundations for collaboration in schools: Utilizing professional learning communities to support teacher candidate learning and visions of teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 979–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoaglund, A.; Birkenfeld, K.; Box, J. Professional learning communities: Creating a foundation for collaboration skills in pre-service teachers. Education 2014, 134, 521–528. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, C.H. Investigating EFL elementary student teachers’ development in a professional learning practicum. In Teachers’ Professional Development in Global Contexts; Mena, J., García-Valcárcel, A., García-Peñalvo, F.J., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, K.K.B. Professional development lost in translation? ‘Organising themes’ in Danish teacher education and how it influences student-teachers’ stories in professional learning communities. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2019, 14, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing-mui So, W. Quality of learning outcomes in an online video-based learning community: Potential and challenges for student teachers. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 40, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M. Kollaboratives Problem-Based Learning. Ein hochschuldidaktischer Ansatz zum Aufbau professionellen Wissens durch problemorientierte und gemeinschaftliche Lernprozesse bei Lehramtsstudierenden. In Professionelle Lerngemeinschaften als Entwicklungsinstrument im Bildungswesen; Kansteiner, K., Stamann, C., Buhren, C., Theurl, P., Eds.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2020; pp. 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann, J. Professionelle Lerngemeinschaften in der universitären Lehrer*innenbildung – eine Vorbereitung auf die unterrichtsbezogene Kooperation im Schulalltag. In Professionelle Lerngemeinschaften als Entwicklungsinstrument im Bildungswesen; Kansteiner, K., Stamann, C., Buhren, C., Theurl, P., Eds.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2020; pp. 240–251. [Google Scholar]

- Funke-Tebart, O. Professionelle Lerngemeinschaften in der zweiten Phase der Lehramtsausbildung – Konzept, Erfahrungen, Perspektiven. In Professionelle Lerngemeinschaften als Entwicklungsinstrument im Bildungswesen; Kansteiner, K., Stamann, C., Buhren, C., Theurl, P., Eds.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2020; pp. 261–273. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsen, M.; Feldmann, J. Professionelle Lerngemeinschaften in der universitären Lehrerbildung. Bundesarbeitskreis Semin.-Fachleiter/Innen EV (BAK) 2018, 2, 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Steinkühler, J. Die Anregung von unterrichtsbezogener Zusammenarbeit in der universitären Lehrer*innenbildung: Ein Seminarkonzept zur kollegialen Kooperation im Lehrberuf. Herausford. Lehr.*Innenbildung—Z. Konzept. Gestalt. Diskuss. 2022, 5, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipiak, A. Gelingende Kooperation durch professionsübergreifende Kommunikation in Professionellen Lerngemeinschaften. In Kommunikationskompetenz. Zwischen Etablierter Praxis und Aktuellen Herausforderungen in den Schulpraktischen Studien; Schöning, A., Cordes-Finkenstein, V., Mell, R., Eds.; Leipziger Universitätsverlag: Leipzig, Germany, 2022; pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Leppert, S. „Ĉu vi parolas Prozess’peranto?“—Ein integrativer Ansatz zur kollaborativen Rekonstruktion von digital transformierten Unternehmensprozessen im Masterstudium der Wipäd Nürnberg. In Digital Literacy in der Beruflichen Lehrer: Innenbildung: Didaktik, Empirie und Innovation; Gerholz, K.-H., Schlottmann, P., Slepcevic-Zach, P., Stock, M., Eds.; wbv Publikation: Bielefeld, Germany, 2022; pp. 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.; Zhao, J. The impact of professional learning communities on pre-service teachers’ professional commitment. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1153016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meihami, H. Exploring the role of professional learning community in EFL student-teachers’ imagined identity development. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rümmele, K. Schon wieder eine Gruppenarbeit?! Professionelle Lerngemeinschaften als kollaboratives Entwicklungsinstrument im Lehramtsstudium. Erzieh. Unterr. 2024, 3–4, 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Theurl, P.; Frick, E. Professionelle Lerngemeinschaften als Mittel der Professionsentwicklung bei Lehramtsstudierenden. In Kooperationsfeld Grundschule-Fokus Grundschule Band 3; Holzinger, A., Kopp-Sixt, S., Luttenberger, S., Wohlhart, D., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2024; pp. 323–335. [Google Scholar]

- Theurl, P.; Frey, A.; Frick, E.; Kikelj-Schwald, E.; Pichler, S.; Rümmele, K. Professionelle Lerngemeinschaften im Bachelorstudium „Lehramt Primarstufe“ – neue Wege in den pädagogisch-praktischen Studien. F&E Edition 2023, 28, 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Reintjes, C.; Thönes, K.V.; Winter, I. Individuelle Professionalisierung durch die Ausbildungselemente Unterricht unter Anleitung und professionelle Lerngemeinschaften aus der Perspektive von Lehramtsanwärter:innen. In Professionalisierung von Lehrkräften im Beruf; Porsch, R., Gollub, P., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2023; pp. 25–52. [Google Scholar]

- Auhl, G.; Daniel, G.R. Preparing pre-service teachers for the profession: Creating spaces for transformative practice. J. Educ. Teaching 2014, 40, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, E.; Theurl, P. Aktionsplan; Pädagogische Hochschule Vorarlberg: Feldkirch, Austria, 2020; (unpublished, available on request). [Google Scholar]

- Theurl, P.; Frick, E.; Barrios, E.; Efstathiadou, M.; Emstad, A.B.; Kansteiner, K.; Knutsen, B.; Lanström, P.; Louca, L.; Rahm, L.; et al. Modell der strukturierten und unterstützten S-PLG-Arbeit. 2022. Available online: https://www.tepinteach.eu/deliverables/#IO3--Final-version-of-the-toolkit-withactivities-to-train-student-teachers-and-mentors-for-successful-PLCs (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Wiliam, D. Changing classroom practice. Educ. Leadersh. 2007, 65, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches to Research, 4th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; McQueen, K.M.; Namey, E.E. Applied Thematic Analysis; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Korthagen, F.A. How teacher education can make a difference. J. Educ. Teaching 2010, 36, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulvik, M.; Smith, K. What characterises a good practicum in teacher education? Educ. Inq. 2011, 2, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulvik, M.; Helleve, I.; Smith, K. What and how student teachers learn during their practicum as a foundation for further professional development. Profess. Dev. Educ. 2018, 44, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admiraal, W.; Schenke, W.; De Jong, L.; Emmelot, Y.; Sligte, H. Schools as professional learning communities: What can schools do to support professional development of their teachers? Profess. Dev. Educ. 2021, 47, 684–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, D. Collaborative Inquiry and the Shared Workspace of Professional Learning Communities. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2017, 31, 1069–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, D.; Whaley, J. Learning together: Practice-centred professional development to enhance mathematics instruction. Math. Teach. Educ. Dev. 2016, 18, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Vescio, V.; Ross, D.; Adams, A. A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzes, J.J.; Marcum, B.; Messerschmidt-Yates, C.; Mark, A. Enhancing self-efficacy in elementary science teaching with professional learning communities. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2013, 24, 1201–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonoubi, R.; Rasekh, A.E.; Tavakoli, M. EFL teacher self-efficacy development in professional learning communities. System 2017, 66, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yin, H.; Liu, Y. Are professional learning communities beneficial for teachers? A multilevel analysis of teacher self-efficacy and commitment in China. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2021, 47, 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæbø, G.I.; Midtsundstad, J.H. How can critical reflection be promoted in professional learning communities? Findings from an innovation research project in four schools. Improv. Sch. 2022, 25, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Theurl, P.; Frick, E.; Barrios, E. Professional Learning Communities of Student Teachers in Internship. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 706. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070706

Theurl P, Frick E, Barrios E. Professional Learning Communities of Student Teachers in Internship. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(7):706. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070706

Chicago/Turabian StyleTheurl, Peter, Eva Frick, and Elvira Barrios. 2024. "Professional Learning Communities of Student Teachers in Internship" Education Sciences 14, no. 7: 706. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070706

APA StyleTheurl, P., Frick, E., & Barrios, E. (2024). Professional Learning Communities of Student Teachers in Internship. Education Sciences, 14(7), 706. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070706