Roma Youth’s Perspective on an Inclusive Higher Education Community: A Hungarian Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Materials and Methods

- How did research participants enter the student society, and were there any support or tools provided to aid access to the organization?

- What motivation and expectations did they have towards the student society at the time of entry?

- What did the student society offer to the research participants and why was this important to them?

4. Results

“I heard about it from X.Y, who I knew from the Faág (Tree Branch) Association”, “XY encouraged me to join, who my father knew.”

“X.Y. (university teacher) caught me in one of her classes and then she said that she would definitely like to see me in the student society, so I should go there. We were in a class together shortly before the MA application and you know, she told me everything and I was hooked by this “woman”… I was like a little kid, I was running after her, I just loved her personality… I was thinking about applying for the MA, after all I already had the BA degree, I could work with it… Anyway, then the student society came, and I carried on.”

“Several of my friends were members of the student society”, “My groupmate told me that I should come here.”

“I joined the student society straight away. You could say I knew about the student society before I applied to university, because my partner was in the student society, and I went to a lot of student society programs as an extern.”

“I’ll meet other people; I’ll have contacts and then things will be easier at university.”

“It was important for me to be in community with young people in roughly similar situations and so I thought, if it is targeting Roma young people, that’s where I could be really good.”

“I was expecting it to be a […] super community where I, the little village girl in the big city, could feel a bit […] enveloped or could provide a safe environment.”

“At the beginning it was financial, but then later there were a lot of courses and programs that I liked. I also liked the weekends anyway. There was joint research, there was language teaching, we also travelled abroad together on study trips. So, it’s a long list… I think I got more than I expected, but I don’t know what my expectations were.”

“…it academically and financially provided me an extra family.”

“You can grow professionally and academically and make friends and build a family at the same time.”

“It’s a great community, lots of experiences, lots of knowledge that you can get by not learning it from a textbook, but by putting it into practice.”

“How nice it was to have our own community room with a computer.”

“Together we started to create a student room for the society and then we felt that, well, we had something.”

“We could talk to each other there, read, study, surf the internet, whatever… We could also talk to the teachers in there a lot… because it’s an awkward situation if you try to get emotional in the teachers’ room, but when we went to the community room, it was easier.”

“What is absolutely great about [student society] is that you know and feel that you are not so disconnected.”

“It was nice to come in after university and be around people I could identify with…”

“For me, the student society gave me a family-like, inclusive environment where I could be with people in similar situations, it gave me a lot of friends that are still with me today…”

“We had a peer mentor who I still have a very good relationship with, and he motivated me a lot and I learned a lot from him…”

“I was always looking out for those who were passive or on the periphery and working on how I could somehow include them. Because a lot of them didn’t know how much of a good community they belonged to, and you need to help them a little bit to feel that.”

“The first real experience that was very defining was our first [student society] Christmas, which was very intimate, and we really had a lot of people here. Then the research in Tisza, that was brilliant too. We went wild down to Tisza and went into the families… that was the first interview of my life, and it was very well organized. We went back in the summer and did this Indian camp. And the trip abroad, Genoa, that was brilliant too.”

“It was such a great experience for me to see the sea for the first time on the trip with the society… I remember turning into Trieste and the whole bus knew that I had never seen the sea before, and the whole bus, even in the back, said ‘look [interviewee’s name, ed.], there’s the sea’, and then I looked out and everyone was looking and was happy that I was happy that there was the sea.”

“I was very scared to speak in community when there were more of us… I was nervous, I couldn’t speak, I was sweating, I had all the problems. I managed to overcome this thanks to the professional. X.Y (instructor) threw me in the deep end several times. We had a research—the Tiszabő research—and it had a conference. It had to be presented. Phew! In Budapest, when we were at university. And then we had to speak in front of everybody. My mentor sat next to me and motivated me. And he/she (the instructor) taught me to always start my talk by talking about myself, introducing myself and then the rest would come. And I still use this when I have to speak.”

“The scholarship helped me not to have to take on another job in addition to university.”

“I came to university as a poor boy and the university provided me with a living. And the student society was everything. But the university gave me enough to bring me a lot of scholarships.”

“There was always someone to turn to at the student society.”

“The tutors helped us with everything, in quotes, they looked after us.”

“So, it’s a Roma student society and somehow there was an opportunity for people from disadvantaged backgrounds to get in. I didn’t identify myself as a Roma, but in the meantime, I learned more about my family, that they were among my ancestors… but I never said it like that, that I was a Roma…”

“When I entered, there was a group of Roma children. Really, everyone looked really weird. Everybody was like chocolate! I saw them and my God, where did I get to! Then the first weekend was so brilliant, I felt like I’d come home. Here I am, starting out on a career as a Roma intellectual, just starting all this, I don’t know what I’m doing. There are a lot of young people here who are already masters’ students, they all have a really strong Roma identity, and it gave me this kind of I don’t know what, kind of strength, that my God, there are so many of us, but it’s cool that we’re going in the same direction and how great it is…”

“The student society is once a refugee, once a home, once someone who slaps us to go through life. We got everything we needed.”

“For a lot of people, it’s a stepping stone that, if it wasn’t for that, a lot of people wouldn’t be able to make a change in that situation in life.”

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Europe 2020. A European Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eu2020/pdf/COMPLET%20EN%20BARROSO%20%20%20007%20-%20Europe%202020%20-%20EN%20version.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation of 12 March 2021 on Roma Equality, Inclusion and Participation 2021/C 93/01. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AJOC_2021_093_R_0001 (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Kende, Á.; Szalai, J. Pathways to Early School Leaving in Hungary; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU Roma Strategic Framework for Equality, Inclusion and Participation for 2020–2030. 2020. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2021-01/eu_roma_strategic_framework_for_equality_inclusion_and_participation_for_2020_-_2030_0.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Cooper, M. (Ed.) Changing the Culture of the Campus: Towards an Inclusive Higher Education—Ten Years on; European Access Network: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M. (Ed.) Student Diversity in Higher Education: Conflicting Realities—Tensions Affecting Policy and Action to Widen Access and Participation; European Access Network: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Claeys-Kulik, A.; Jørgensen, T.E.; Stöber, H. Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in European Higher Education Institutions. Results from the INVITED Project. 2019. Available online: https://eua.eu/resources/publications/890:diversity,-equity-and-inclusion-in-european-higher-education-institutions-results-from-the-invited-project.html (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Hoffman, J.; Blessinger, P.; Makhanya, M. (Eds.) Strategies for Facilitating Inclusive Campuses in Higher Education. International Perspectives on Equity and Inclusion; Innovations in Higher Education Teaching and Learning; Emerald Publishing Limited: Howard House, UK, 2019; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Milem, J.; Chang, M.; Antonio, A. Making Diversity Work on Campus: A Research-Based Perspective; Association of American Colleges and Universities: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.; Berger, J.; McClendon, S. Toward a Model of Inclusive Excellence and Change in Postsecondary Institutions; Association of American Colleges and Universities: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, G.; Bustillos, L.T.; Bensimon, E.M.; Brown, C.; Bartee, R. Achieving Equitable Educational Outcomes with All Students: The Institution’s Roles and Responsibilities; Association of American Colleges and Universities: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado, S.; Alvarez, C.L.; Guillermo-Wann, C.; Cuellar, M.; Arellano, L. A Model for Diverse Learning Environments. The Scholarship on Creating and Assessing Conditions for Student Success. In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, 27; Smart, J.C., Paulsen, M.B., Eds.; Springer Science Business Media B.V.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 41–122. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, J.; Targett, N. Developing and Sustaining Inclusive Excellence and a Safe, Healthy, Equitable Campus Community at UNH; Interim Report Presidential Task Force on Campus Climate: Durham, NH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, A.; Vitéz, K.; Orsós, I.; Fodor, B.; Horváth, G. Diversity and Inclusion in Higher Education. Train. Pract. 2021, 19, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

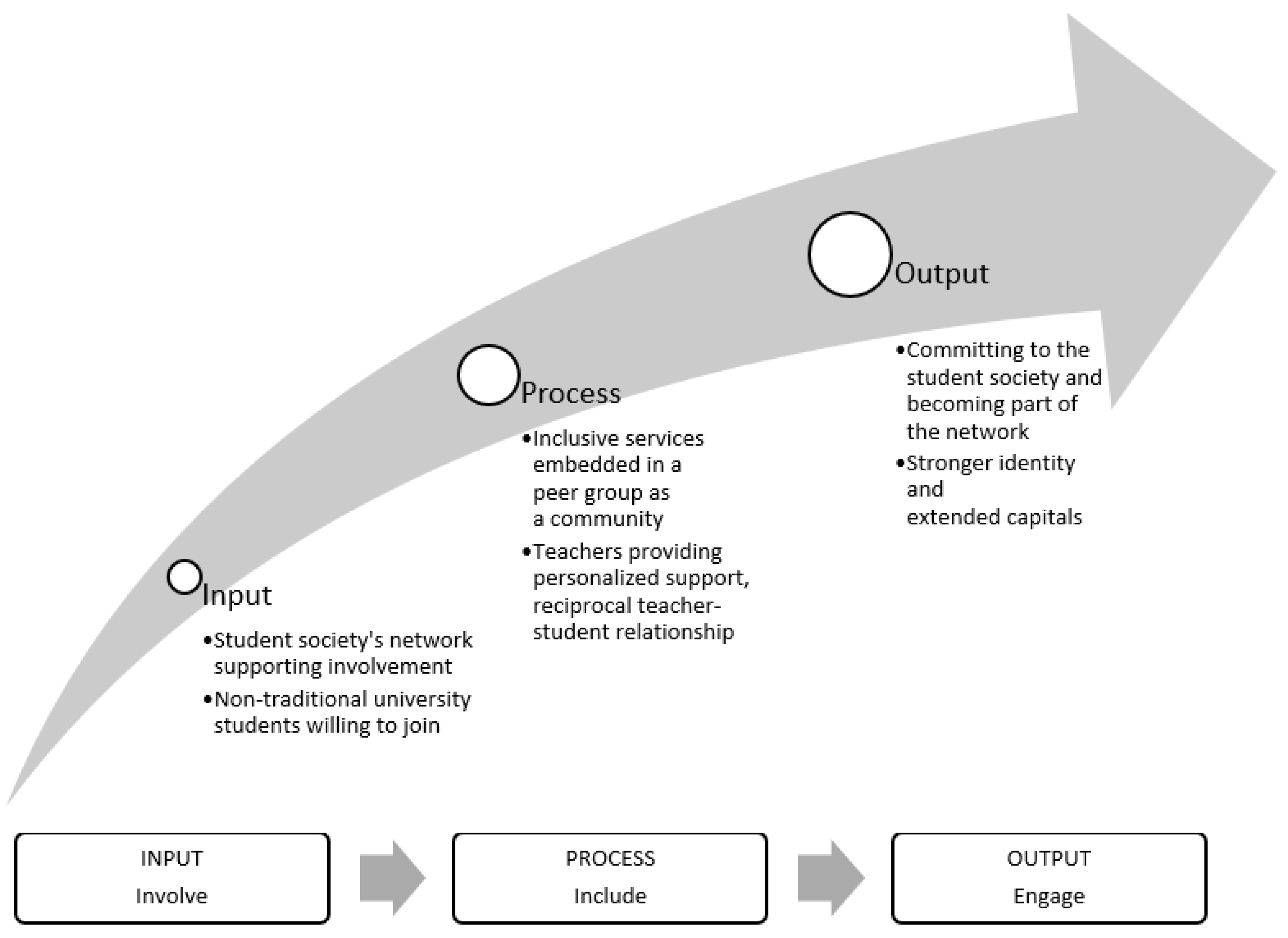

- Varga, A.; Trendl, F. Roma Youth and Roma Student Societies in the Hungarian Higher Education in the Light of Process-based Model of Inclusion. Auton. Responsib. J. Educ. Sci. 2022, 7, 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, L. The Casey Review: A Review into Opportunity and Integration; Department for Communities and Local Government: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Burgstahler, S. Universal Design of Higher Education: From Principles to Practice, 2nd ed.; Harvard Education Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Carmona, T.; González-Monteagudo, J.; Tenorio Rodríguez, M.A. Lights and Shadows: The Inclusion of Invisible Students in Spanish Universities. Auton. Responsib. J. Educ. Sci. 2022, 7, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J.; Vajda, V. Navigating Power and Intersectionality to Address Inequality. IDS Work. Pap. 2017, 504. Available online: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/13431/Wp504_Online.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Durst, J.; Bereményi, Á. “I felt I arrived home”: The minority trajectory of mobility for first-in-family Hungarian Roma graduates. In Social and Economic Vulnerability of Roma People; Mendes, T.M.M., Magano, O., Toma, S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 229–249. [Google Scholar]

- Naudet, J. Stepping into the Elite. Trajectories of Social Achievement in India, France, and the United States; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Teodorović, J. Student background factors influencing student achievement in Serbia. Educ. Stud. 2012, 38, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereményi, Á.; Durst, J.; Nyírő, Z. Reconciling habitus through third spaces: How do Roma and non-Roma first-in-family graduates negotiate the costs of social mobility in Hungary? Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2023, 54, 460–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Velux Foundations 2019. Roma in Europe—A Report for the Velux Foundations. Work. Pap. 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341111319_2019_Roma_in_Europe (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Frazer, H.; Marlier, E. Promoting the Social Inclusion of Roma. Synth. Rep. 2011. Available online: https://www.gitanos.org/upload/44/11/synthesis_report_2011-2_final_3_1_.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Kruczek-Steiger, E.; Simmons, C. The Roma: Their history and education in Poland and the UK. Educ. Stud. 2021, 27, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha, A.; Abad-Merino, S.; Macías-Aranda, F.; Segovia-Aguilar, B. Roma University Students in Spain: Who Are They? Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosso, T.J. Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth. Race Ethn. Educ. 2005, 8, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereményi, Á.; Carrasco, S. Bittersweet success: The impact of academic achievement among the Spanish Roma after a decade of Roma Inclusion. In Second International Handbook of Urban Education; Pink, W.T., Noblit, G.W., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1169–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Carmona, T.; González-Monteagudo, J.; Soria-Vílchez, A. Gitanos en la Universidad: Unestudio de caso de trayectorias de éxito en la Universidad de Sevilla; Ministerio de Educación: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Messing, V.; Molnár, E. Bezáródó kapcsolati hálók: Szegény roma háztartások kapcsolati jellemzői. Esély 2011, 22, 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Óhidy, A. A ‘roma közösségi kulturális tőke’ szerepe roma és cigány nők sikeres iskolai pályafutásában—Egy kvalitatív kutatás eredményei. Magy. Pedagógia 2016, 116, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forray, R.K.; Óhidy, A. The situation of Roma women in Europe: Increasing success in education—Changing roles in family and society. Hung. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Beremény, Á.; Durst, J. Meaning Making and Resilience Among Academically High-Achieving Roma Women. Szociológiai Szle. 2021, 31, 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehérvári, A. The role of teachers’ views and attitudes in the academic achievement of Roma students. J. Multicult. Educ. 2023, 17, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayman, J.; Varga, A. Resilience and Inclusion. Romológia 2015, 3, 12–30. [Google Scholar]

- Goenechea, C.; Gallego-Noche, B.; Fernández, F.J. A Who I am and who I share it with. Roma university students between invisibility and empowerment. Intercult. Educ. 2022, 33, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, J.; Bogdán, P.; Durst, J. Accumulating Roma cultural capital: First-in-family graduates and the role of educational talent support programs in Hungary in mitigating the price of social mobility. Rev. Sociol. 2021, 31, 74–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, M.M.; Magano, O.; Mourão, S.; Pinheiro, S. In-between identities and hope in the future: Experiences and trajectories of Cigano secondary students (SI). Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2023, 54, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocsi, V.; Ceglédi, T. Is the glass ceiling inaccessible? The educational situation of Roma youth in Hungary. Balk. Forum 2021, 30, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, A.; Trendl, F.; Vitéz, K. Development of positive psychological capital at a Roma Student College. Hung. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 10, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukács, J.Á.; Szabó, T.; Huszti, É.; Komolafe, C.; Ember, Z.; Dávid, B. The role of colleges for advanced studies in Roma undergraduates’ adjustment to college in Hungary from a social network perspective. Intercult. Educ. 2023, 34, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunajeva, J. University Mentoring Programs during the Pandemic: Case Study of Hungarian Roma University Students. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of People | Gender | Social Background | Being of a Minority | Duration Spent in the Student Society | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | Disadvantaged Background | Non-Disadvantaged Background | Roma | Non-Roma | Not More than 1 Year | 1–2 Years | More than 2 Years | ||

| Interviewed (Research sample) | No. | 50 | 22 | 28 | 43 | 7 | 39 | 11 | 17 | 17 | 15 |

| % | 37.3% | 44.0% | 56.0% | 86.0% | 14.0% | 78.0% | 22.0% | 34.0% | 34.0% | 30.0% | |

| Not interviewed (Not in the sample) | No. | 84 | 33 | 51 | 63 | 21 | 54 | 30 | 61 | 17 | 4 |

| % | 62.7% | 39.3% | 60.7% | 75.0% | 25.0% | 64.3% | 35.7% | 72.6% | 20.2% | 4.8% | |

| Total | No. | 134 | 55 | 79 | 105 | 29 | 93 | 41 | 78 | 34 | 19 |

| % | 100.0% | 41.0% | 59.0% | 79.1% | 20.9% | 69.4% | 30.6% | 58.2% | 25.4% | 14.2% | |

| Distribution (N) | From a Society Student | Teacher from Secondary School | University Teacher | Internet | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disadvantaged background | 43 | 17 | 4 | 21 | 4 |

| Non-Disadvantaged background | 7 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Roma | 39 | 16 | 4 | 18 | 3 |

| Non-Roma | 11 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 2 |

| Total participants mentioning the category | 50 | ||||

| All mentions | 54 | 20 | 4 | 25 | 5 |

| Distribution | N | Educational Support | Inclusive Community | Programs | Financial Support | Teachers’ Support | Roma Identity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected | Disadvantaged background | 43 | 8 | 27 | 6 | 15 | 8 | 3 |

| Got | 23 | 39 | 23 | 20 | 34 | 10 | ||

| Expected | Non-Disadvantaged background | 7 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Got | 4 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Expected | Roma | 39 | 6 | 28 | 5 | 14 | 8 | 3 |

| Got | 21 | 37 | 20 | 18 | 32 | 11 | ||

| Expected | Non-Roma | 11 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Got | 6 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 0 | ||

| Expected | Total | 50 | 9 | 33 | 7 | 16 | 9 | 3 |

| Got | 27 | 46 | 24 | 22 | 38 | 11 |

| Distribution | N | Educational Support | Inclusive Community | Programs | Financial Support | Teachers’ Support | Roma Identity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected | Total | 50 | 9 | 33 | 7 | 16 | 9 | 3 |

| Got | 10 | 34 | 12 | 1 | 25 | 1 |

| Number of Mentioned Benefits | Mentioning at Least Once | Mentioning at Least Twice | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| 0 | - | - | 7 | 14.0 |

| 1 | 5 | 10.0 | 16 | 32.0 |

| 2 | 9 | 18.0 | 15 | 30.0 |

| 3 | 11 | 22.0 | 9 | 18.0 |

| 4 | 15 | 30.0 | 3 | 6.0 |

| 5 | 8 | 16.0 | ||

| 6 | 2 | 4.0 | ||

| Total | 50 | 100.0 | 50 | 100.0 |

| Yes | No | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disadvantaged background | N | 24 | 19 | 43 |

| Non-Disadvantaged background | N | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Total | N | 26 | 24 | 50 |

| Roma | N | 23 | 16 | 39 |

| Non-Roma | N | 3 | 8 | 11 |

| Total | N | 26 | 24 | 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Varga, A.; Horváth, G.; Trendl, F. Roma Youth’s Perspective on an Inclusive Higher Education Community: A Hungarian Case Study. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 679. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070679

Varga A, Horváth G, Trendl F. Roma Youth’s Perspective on an Inclusive Higher Education Community: A Hungarian Case Study. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(7):679. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070679

Chicago/Turabian StyleVarga, Aranka, Gergely Horváth, and Fanni Trendl. 2024. "Roma Youth’s Perspective on an Inclusive Higher Education Community: A Hungarian Case Study" Education Sciences 14, no. 7: 679. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070679

APA StyleVarga, A., Horváth, G., & Trendl, F. (2024). Roma Youth’s Perspective on an Inclusive Higher Education Community: A Hungarian Case Study. Education Sciences, 14(7), 679. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070679