“Two Sides of the Same Coin”: Benefits of Science–Art Collaboration and Field Immersion for Undergraduate Research Experiences

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Merging of Arts and Sciences in Undergraduate Education

1.2. CUREs and Field Experiences

1.3. The Need for Art in Science Communication and Inquiry

“Asking questions is central to science and is largely motivated by confusion or surprise; argumentation and problem solving are the means to pursue questions and are often driven by frustration, confusion, or the anticipated joy of discovery.”

1.4. Current Study and Research Questions

- How does the inclusion of art–science collaborations in an interdisciplinary art–science CURE influence students’ understanding of the scientific method and enhance their science communication skills?

- How does the addition of an immersive travel abroad field research experience impact student perspective and career goals (in art and science)?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Art–Sscience Course and Participating Students

2.2. Study Framework

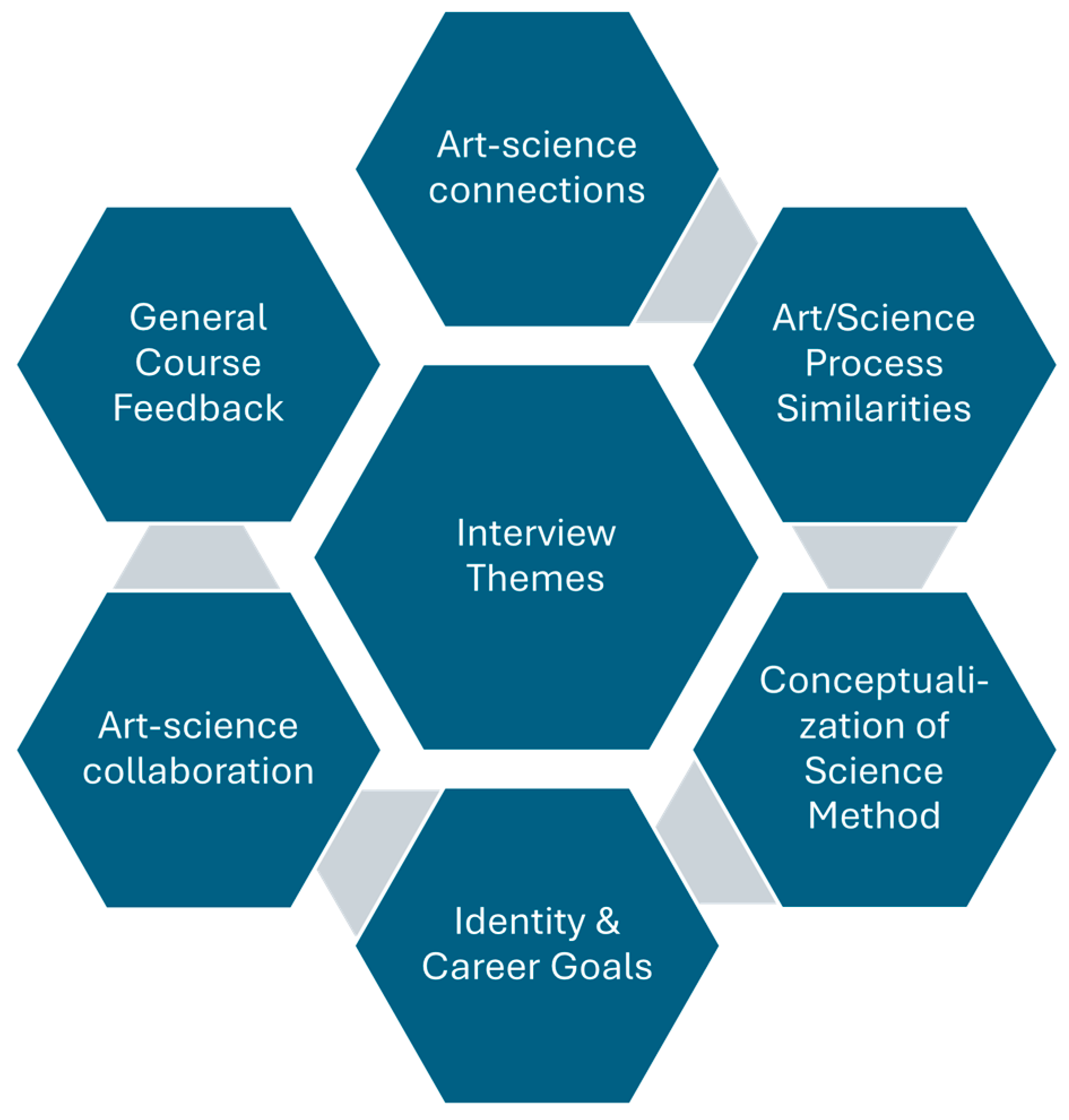

2.3. Qualitative Analysis: Themes

2.4. Survey Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Interview Themes and Responses

3.1.1. Connections between Science and Art

“Well, before I always thought that art and science were two sides of the same coin… they both use a similar process of coming up with an idea, then going through experiments with trial and error.”

3.1.2. Conceptualization of the Scientific Method

“Science has bounds. And if you can’t work within that frame, the science would not have the validity.”

“The difference is that there’s no creativity. When you’re in … a gen chem lab … you can’t come up with a new idea and then be like, oh, I want to try this out. You have to stick to this protocol. When I say I want to do more research, I think I’m referring to ... extracurricular stuff because in the chem labs and stuff like that, I don’t think I would ever feel like that discovery ... a rush, I guess.”

3.1.3. Process Similarities between Science and Art

“You have a general idea of what you want to do. So, for me and xxx we just wanted to use some trail cams. And then you narrow it down into more of a concrete idea, and what you want to show, what you want to prove.”

“If you are attempting a new method of process and it doesn’t work, then, you make note of that. You go back and you try something new. That would probably be the closest thing to scientific method.”

3.1.4. Art/Science Identity and Career Goals

“[The University] gives you a fair amount of hands-on experience, through different laboratories, but it’s nice to go through the entire process of designing an experiment, and carrying it out, and figuring out what materials you need and everything. So I definitely feel more confident graduating after taking this class.”

“(The program) ended up changing my focus … Instead of just focusing on performance art, I’m also now focusing on critical theory because I think that it was really beneficial to my growth both personally, and as an artist to be pushed to do more of that research.”

“So I’ve always wanted to either do field work or lab work when I start a career. But just last night when we were working on the art project, [project partner] brought up the scientific artist job, and now [professor] talked about it earlier and that seemed interesting as well to me, because I do like drawing and it’d be like a good way to incorporate my hobby.”

3.1.5. Science Poster and Artwork Collaboration

“I’ll say that actually did learn quite a bit from [science partner], I never actually done a real scientific experiment and she actually taught me how to do it in a professional manner.”

“I’ve made sure that my group has had a say in what I’m making from the very beginning, I don’t want it to be [name’s] piece. I let them know what I’m doing. I involve them in what I’m doing.”

“I didn’t realize that we weren’t on the same page. So it was like they [art student] had all these great ideas, yes, and I would tell them that they were great ideas, but I’m like, no, we can’t do that. That’s not in the scope of our project. We can’t be looking at reindeer when we’re doing birds. We can’t be looking at people and culture when we’re doing birds. So mine was very like, this is your path, do not step a foot off the path. Whereas with the art, like I was trying to, and I realized this there too, I was trying to make that same box around their art too. And then it was a teachable moment that they had to teach me like, look like art’s not like that. Yes, I’m not going to involve reindeer, but I’m going to involve a little bit of culture when I’m dealing with the man part of does man have an impact on birds.”

3.1.6. Course Feedback

“I thought we were going to be paired with an actual artist major. So that’s the main reason I thought it’d be a good collaboration.”

3.1.7. Travel Abroad Experience

“Experiencing new cultures and people because that kind of diversity that we are experiencing helped us think in different ways that we might not have before.”

“I haven’t been around so much research and so many people deeply involved in science.”

“Being at the research station, you feel the need to be a little more social because you’re away from home. What do you do? Sit in your room. That wasn’t for me. So I wanted to go talk to the people, get to know them.”

3.2. Quantitative Survey Findings

3.2.1. Pre- vs. Post-Course Differences

3.2.2. Local vs. Travel Groups

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Before the course, did you see connections between science and art, and if not, has that changed after the course?

- Has this course changed how you conceptualize the scientific method? Do you think it is a necessary part of the scientific process, or does it limit creativity?

- Do you see any similarities between the processes that artists use to create a work of art and scientific research?

- As a result of participating in the course, has your identity as a scientist (or artist) changed in any way? Has your career path changed?

- How was your experience developing the presentation for the exhibit/installation? The poster and the work of art? And collaborating with your partner?

- Do you have any feedback about the course?

- For the travel abroad students ONLY. Was travelling abroad an important part of your course experience?

References

- Root-Bernstein, R.; Allen, L.; Beach, L.; Bhadula, R.; Fast, J.; Hosey, C.; Kremkow, B.; Lapp, J.; Lonc, K.; Pawelec, K.; et al. Arts foster scientific success: Avocations of Nobel, National Academy, Royal Society, and Sigma Xi members. J. Psychol. Sci. Technol. 2008, 1, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Goyal, Y. Art and science: Intersections of art and science through time and paths forward. Embo Rep. 2019, 20, e47061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejias, S.; Thompson, N.; Sedas, R.M.; Rosin, M.; Soep, E.; Peppler, K.; Roche, J.; Wong, J.; Hurley, M.; Bell, P.; et al. The trouble with STEAM and why we use it anyway. Sci. Educ. 2021, 105, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounsbury, J.W.; Foster, N.; Patel, H.; Carmody, P.; Gibson, L.W.; Stairs, D.R. An investigation of the personality traits of scientists versus nonscientists and their relationship with career satisfaction. R&D Manag. 2012, 42, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payton, F.C.; White, A.; Mullins, T. STEM Majors, Art Thinkers (STEM + Arts)—Issues of Duality, Rigor and Inclusion. J. STEM Educ. 2017, 18, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Segarra, V.A.; Natalizio, B.; Falkenberg, C.V.; Pulford, S.; Holmes, R.M. Steam: Using the arts to train well-rounded and creative scientists. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 2018, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnon, D.; Voss-Andreae, J.; Stanley, J. Integrating Art and Science in Undergraduate Education. PLOS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forget, B.E. Merging dualities: How convergence points in art and science can (re)engage women with the STEM field. Can. Rev. Art Educ. 2021, 48, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanko, J.S.; Shekhter, I.; Kyle, R.R.; Di Benedetto, S.; Birnbach, D.J. Establishing a Convention for Acting in Healthcare Simulation: Merging Art and Science. Simul. Heal. J. Soc. Med. Simul. 2013, 8, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.; Calabrese Barton, A. Towards critical justice: Exploring intersectionality in community-based STEM-rich clmaking with youth from non-dominant communities. Equity Excell. Educ. 2018, 51, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, P.; Patel, M.; Johnson, E.; Weiss, M.; Auerbach, A.J.; Schussler, E.; Stains, M.E.M.; Perera, V.; Mead, C.; Buxner, S.; et al. Active Learning and Student-centered Pedagogy Improve Student Attitudes and Performance in Introductory Biology. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2009, 8, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, E.; Hewitt, N.M. Talking about Leaving: Why Undergraduates Leave the Sciences; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1996; ISBN 0-8133-8926-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lom, B. Classroom activities: Simple strategies to incorporate student-centered activities within undergraduate science lectures. J. Undergrad. Neurosci. Educ. 2012, 11, A64–A71. [Google Scholar]

- Ehtiyar, R.; Baser, G. University education and creativity: An assessment from students’ perspective. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2019, 19, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glăveanu, V.P. Revisiting the “Art Bias” in Lay Conceptions of Creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2014, 26, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, J.T.; Ryba, R.; Connell, S.D. Sparking Creativity in Science Education. J. Creative Behav. 2021, 55, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Khaire, M. Creativity and the role of the leader. In Harvard Business Review; Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation: Boston, MA, USA, 2008; Volume 86, pp. 100–142. [Google Scholar]

- Masnick, A.M.; Valenti, S.S.; Cox, B.D.; Osman, C.J. A Multidimensional Scaling Analysis of Students’ Attitudes about Science Careers. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2010, 32, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.; Haaf, M. Investigating Art Objects through Collaborative Student Research Projects in an Undergraduate Chemistry and Art Course. J. Chem. Educ. 2013, 90, 1616–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, S.J.; Rock, R.K.; Morris, J. Interdisciplinary STEM education reform: Dishing out art in a microbiology la-boratory. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018, 365, fnx245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, P.; Hasni, A. Interest, motivation and attitude towards science and technology at K-12 levels: A systematic review of 12 years of educational research. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2014, 50, 85–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, L.Z.; Hammer, D. Learning to Feel Like a Scientist. Sci. Educ. 2016, 100, 189–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fensham, P.J. Real world contexts in PISA science: Implications for context-based science education. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2009, 46, 884–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelsman, J.; Ebert-May, D.; Beichner, R.; Bruns, P.; Chang, A.; DeHaan, R.; Gentile, J.; Lauffer, S.; Stewart, J.; Tilghman, S.M.; et al. Scientific teaching. Science 2004, 304, 521–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilson, L. Teaching at Its Best: A Research-Based Resource for College Instructors, 3rd ed.; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Fransisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ballen, C.J. Correction for A Call to Develop Course-Based Undergraduate Research Experiences (CUREs) for Nonmajors Courses. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2017, 16, co5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hofstein, A.; Navon, O.; Kipnis, M.; Mamlok-Naaman, R. Developing students’ ability to ask more and better questions resulting from inquiry-type chemistry laboratories. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2005, 42, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh, G.D.; Cruce, T.M.; Shoup, R.; Kinzie, J.; Gonyea, R.M. Unmasking the effects of student engagement on first-year college grades and persistence. J. High. Educ. 2008, 79, 540–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatto, D. Undergraduate Research Experiences Support Science Career Decisions and Active Learning. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2007, 6, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shortlidge, E.E.; Bangera, G.; Brownell, S.E. Faculty Perspectives on Developing and Teaching Course-Based Under-graduate Research Experiences. Bioscience 2016, 66, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangera, G.; Brownell, S.E. Course-based undergraduate research experiences can make scientific research more inclusive. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2014, 13, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duboue, E.R.; Kowalko, J.E.; Keene, A.C. Course-based undergraduate research experiences (CURES) as a pathway to diversify science. Evol. Dev. 2022, 24, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, C.M.; Cisneros, M.R. Vertically-Integrated Course-Based Undergraduate Research Experiences (CUREs) Structure a Biomedical Research Certificate Program that Promotes Inclusivity. FASEB J. 2022, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, P.J.; Levine, R.; Flessa, K.W. Choosing the Geoscience Major: Important Factors, Race/Ethnicity, and Gender. J. Geosci. Educ. 2015, 63, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, B.A. Introductory geosciences at the two-year college: Factors that influence student transfer intent with geoscience degree aspirations. J. Geosci. Educ. 2018, 66, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, B.; Martin, T. Two-Year Community: Design and Components of a Two-Year College Interdisciplinary Field-Study Course. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 2013, 43, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.A.; Lickel, B.; Markowitz, E.M. Reassessing emotion in climate change communication. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 850–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, A.; Markowitz, E.; Pidgeon, N. Public engagement with climate change: The role of human values. WIREs Clim. Change 2014, 5, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, A.; Born, G.; Weszkalnys, G. Logics of interdisciplinarity. Econ. Soc. 2008, 37, 20–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, G.; Barry, A. ART-SCIENCE: From public understanding to public experiment. J. Cult. Econ. 2010, 3, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root-Bernstein, R.S. Aesthetic cognition. Int. Stud. Philos. Sci. 2002, 16, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldous, C.R. Creativity, problem solving and innovative science: Insights from history, cognitive psychology and neuroscience. Int. Educ. J. 2007, 8, 176–186. [Google Scholar]

- Radoff, J.; Jaber, L.Z.; Hammer, D. “It’s Scary but It’s Also Exciting”: Evidence of Meta-Affective Learning in Science. Cogn. Instr. 2019, 37, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditty, J.L.; Kvaal, C.A.; Goodner, B.; Freyermuth, S.K.; Bailey, C.; Britton, R.A.; Gordon, S.G.; Heinhorst, S.; Reed, K.; Xu, Z.; et al. Incorporating Genomics and Bioinformatics across the Life Sciences Curriculum. PLOS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilanova, C.; Porcar, M. iGEM 2.0—Refoundations for engineering biology. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaz, K.; Thornberg, R. The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leedy, P.D.; Ormrod, J.E. Practical Research: Planning and Design, 8th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, T.P.; Olson, A.M. The Third Minnesota Report Card on Environmental Literacy. Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. 2008. Available online: http://seek.minnesotaee.org/sites/default/files/reportcard2008.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2019).

- Cotton, D.R.; Alcock, I. Commitment to Environmental Sustainability in the UK Student Population. Stud. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 1457–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschbacher, P.R.; Li, E.; Roth, E.J. Is science me? High school students’ identities, participation and aspirations in science, engineering, and medicine. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2010, 47, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, J.; Taylor, P.C.; Chen, C.C. Development, validation and use of the beliefs about science and school science questionnaire (BASSSQ). In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the National Association for Research on Science Teaching, Chicago, IL, USA, 16–19 April 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Halloun, I. Student Views about Science: A Comparative Survey; Beirut Phoenix Series/Educational Research Center, Lebanese University: Beirut, Lebanon, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Halloun, I.; Hestenes, D. Interpreting VASS Dimensions and Profiles for Physics Students. Sci. Educ. 1998, 7, 553–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kier, M.W.; Blanchard, M.R.; Osborne, J.W.; Albert, J.L. The Development of the STEM Career Interest Survey (STEM-CIS). Res. Sci. Educ. 2014, 44, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, C.C.M. Scientific Practice and Science Education. Sci. Educ. 2015, 99, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrin, S.; Short-Meyerson, K.; Edwards, C.; Quinones-Diaz, R. “What’s Your Hypothesis?” Influence of Topic, Ethnicity, and Gender on Fourth Graders’ Science Performance [Poster Session]. AERA Annual Meeting San Francisco, CA, USA, 17–21 April. Available online: http://tinyurl.com/ukfbmpr (accessed on 6 March 2024).

| Identity | Number of Students in Post-Survey |

|---|---|

| Female | 25 |

| Male | 14 |

| Gender non-binary/non-conforming | 2 |

| African American | 2 |

| Asian | 4 |

| Caucasian | 20 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 15 |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 |

| Native Alaskan | 1 |

| Native American | 1 |

| Average Age 1 | 24.1 years old |

| Question | Response Codes | Number of Responses: Local | Number of Responses: Travel Abroad |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Connections between science and art | • Always saw a connection between science and art. | 1 | 4 |

| • After course, saw a new connection or deeper connection. | 5 | 7 | |

| • Specific connections were noted. “Both require…” See below. | 1–2 | 1–3 | |

| 2. Conceptualization of scientific method | • It provides a necessary framework, structure, boundary, or pathway to obtain consistent results. • Good guideline, but process must be flexible to allow for backtracking to redesign hypothesis or experimental design if found to be flawed. | 2 | 7 |

| 3 | 9 | ||

| 3. Process similarities—science and art | • Starts with brainstorming and inspiration. | 3 | 4 |

| • Trial and error involved in process. | 1 | 4 | |

| • Product is novel or original. | - | 5 | |

| 4. Change in science (or art) identity? | • More confident about identity, skills and career goals. | 3 | 6 |

| • Developed skills that integrate art and science | 2 | 6 | |

| • Expanded perspective on career fields and how art and science careers intersect. | 1 | 4 | |

| • Confidence/interest in field work. | 2 | 3 | |

| • Ability to work independently on a “real world” project. | 2 | 3 | |

| 5. Science poster and artwork collaboration | • Took more time than students predicted. | 2 | 3 |

| • Wanted more collaboration between art and science students. | - | 4 | |

| • Students found collaboration between art and science students to be enjoyable and product was more professional. * | - | 5 | |

| 6. Course feedback | • More art time and supplies. | - | 4 |

| • Encourage more collaboration between art and science students. | - | 5 | |

| • A more extended course schedule, not such a concentrated time frame. * | - | 4 | |

| 7. Travel abroad experience important? * | • Enabled students to compare ecosystems in a pristine ecosystem. | - | 6 |

| • Experienced new cultures and perspectives, different ways of thinking. | - | 7 | |

| • Learned about research from students, scientists and artists from other countries. Encouraged them to pursue research. | - | 7 | |

| • Isolation and time away from distractions emphasized work and bonding as a group. | - | 5 |

| Theme | Survey Statements | Compare Travel vs. Local | Compare Pre- vs. Post-Course | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Mean | Travel Mean | p-Value | Pre-Mean | Post-Mean | p-Value | ||

| Connection between science and art | I have seen art that depicts environmental issues. | 5.8 | 6.3 | 0.19 | 5.1 | 6.1 | 0.001 |

| I feel that art is an appropriate medium for influencing the public’s ideas about environmental issues. | 6.3 | 6.4 | 0.80 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 0.63 | |

| Science, art and science process self-efficacy | I am able to earn a good grade in my science classes. | 6.3 | 6.3 | 0.93 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 0.68 |

| I am able to earn a good grade in my arts classes. | 5.8 | 6.2 | 0.39 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 0.92 | |

| I will be able to complete the requirements for the degree I am seeking. | 6.6 | 6.9 | 0.15 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 0.82 | |

| I am confident that I can use technical lab science skills (such as use lab tools, instruments and techniques). | 6.2 | 5.7 | 0.10 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 0.20 | |

| I am confident that I can generate a research question to answer. | 6.5 | 6.5 | 0.91 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 0.04 | |

| I am confident that I can figure out what data/observations to collect and how to collect them. | 6.5 | 6.2 | 0.36 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 0.05 | |

| I am confident that I can create explanations for the results of the study. | 6.5 | 6.6 | 0.75 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 0.38 | |

| I am confident in my ability to think and work creatively. | 5.7 | 6.2 | 0.26 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 0.65 | |

| (Pre) Conceptions About Science and Art Ability | I am nervous about taking an art class because I feel that I am just not “artsy” enough. | 2.5 | 1.9 | 0.15 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 0.57 |

| I am nervous about taking a science class because I feel that I am just not good at science. | 1.7 | 1.4 | 0.41 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 0.91 | |

| Mindset (and Goals) | Learning (and doing) science requires a special talent. | 2.0 | 1.9 | 0.85 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 0.46 |

| Learning (and doing) art requires a special talent. | 2.6 | 2.3 | 0.39 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 0.42 | |

| Sense of Belonging | I enjoy learning about science. | 4.8 | 4.8 | 0.99 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 0.79 |

| I enjoy learning about art. | 4.2 | 4.5 | 0.37 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 0.76 | |

| Science and Art Collaboration | Scientists should work collaboratively—it is important to the scientific process to share ideas and findings. | 4.2 | 4.8 | 0.01 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 0.78 |

| Artists should work collaboratively—it is important to the artistic process to share their ideas and creations. | 3.6 | 4.4 | 0.04 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 0.38 | |

| Collaborations between scientist and artists can lead to innovation and a new way of thinking about and addressing societal issues. | 4.6 | 4.8 | 0.24 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 0.59 | |

| Collaborations between scientists and artists can lead to more creative ways to share information about societal issues with the public. | 4.6 | 4.9 | 0.16 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 0.84 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sandrin, S.; Ball, B.; Arora, I. “Two Sides of the Same Coin”: Benefits of Science–Art Collaboration and Field Immersion for Undergraduate Research Experiences. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060620

Sandrin S, Ball B, Arora I. “Two Sides of the Same Coin”: Benefits of Science–Art Collaboration and Field Immersion for Undergraduate Research Experiences. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(6):620. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060620

Chicago/Turabian StyleSandrin, Susannah, Becky Ball, and Ishanshika Arora. 2024. "“Two Sides of the Same Coin”: Benefits of Science–Art Collaboration and Field Immersion for Undergraduate Research Experiences" Education Sciences 14, no. 6: 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060620

APA StyleSandrin, S., Ball, B., & Arora, I. (2024). “Two Sides of the Same Coin”: Benefits of Science–Art Collaboration and Field Immersion for Undergraduate Research Experiences. Education Sciences, 14(6), 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060620