Abstract

This study explores academic middle managers’ perspectives on a mission-driven university strategy in a Danish context, offering insights for institutions implementing similar strategies. The case of a Danish university highlights the vital role of academic middle managers in navigating strategic uncertainty. Success requires a nuanced understanding of organizational dynamics and aligning initiatives with institutional goals. The study, based on interviews with ten academic middle managers, reveals complexities and challenges associated with mission-driven innovation in higher education, through a phenomenographic and thematic analysis, concerning current impressions and experiences, the perceived barriers to implementation, and the perceived affordances of transforming into a mission-driven university. The findings emphasize the significance of overcoming internal resistance and establishing institutional support, providing valuable considerations for higher education institutions and their academic middle managers in implementing mission-driven innovation strategies, and have the potential to support the design and implementation of future higher education strategies for sustainability, pertaining to the responsibilities, interactions, and mediations across and among the upper management and the academic staff.

1. Introduction

Higher education institutions (HEIs) have gradually transformed over the last three decades, becoming increasingly commercialized and efficiency-driven [1]. The signs of this transformation have gradually influenced HEIs, and are highlighted to entail new funding mechanisms, competition for student intake, and an emphasis on branding and sloganeering [2]. This shift has led to the emergence of entrepreneurial universities that are driven by economic demands and are required to develop institutional strategies that directly adhere to national policies. In addition, it also entails a stronger emphasis on industry collaboration and the crossing of disciplinary boundaries for education and research [3,4,5].

HEIs, while crucial to society, face constraints as they pursue multifaceted missions prioritizing both economic and technological innovation and growth [6,7]. This paper examines a specific strategy unfolding in a higher education institution conceptualized as mission-driven innovation, originating from the European Union and the United Nations. The framework is grounded in the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs), which have been central to the development of the concept. Mazzucato [8] who has been a central figure in the design, defines mission-driven innovation as systemic public policies that draw on frontier knowledge to attain specific goals, or “big science deployed to meet big problems”. Mission-driven innovation is proposed to then serve as a political instrument for HEIs to apply in their institutional practices, such as collaborative research proposals in line with the UNSDGs. Universities shall then, in return, direct their attention towards initiating mission-driven innovation research projects and mission portfolios. These, by intention, shall serve as sub-parts to future solutions on a single or multiple UNSDGs [8,9].

The UNSDGs have been established by the support and affirmation at a supranational level, meaning the UNSDGs do not carry profound legal leverage. Therefore, each member state shall attempt to adhere to commonly decided-upon strategies and to develop national policies concerning the UNSDGs—which mission-driven innovation is perceived as a possible approach to realizing the prospects [10]

Mission-driven innovation emphasizes stakeholder involvement from various sectors, including universities and research institutions, in addressing global challenges [11,12]. Due to the complexity of universities’ structural conditions and the multifaceted research cultures existing, mission-driven innovation is proposed as a solution for research institutions to be embedded in ongoing and future collaborative processes [9,12]. Universities recognizing the relevance of mission-driven innovation as a precursor for solving the 17 UNSDGs shall then organize, accommodate, and facilitate collaborations across sectors producing scientific results and contributing to potential solutions [8,13].

Academic institutional leaders serve a vital role in implementing research initiatives within HEIs. However, middle managers’ perceptions of the challenges and opportunities related to the mission-driven innovation approach vary across disciplines, departments, and faculties. Leadership and management within HEIs are tasked with implementing strategic processes and adopting systemic models for change. Academic middle managers occupy a unique position with significant influence over the execution of upper management decisions [14]. Their roles involve formalized management and organizational change, presenting them with complex professional challenges that include navigating potentially eroding collegial relationships, managing economic realities, and addressing established academic cultures and practices. Despite extensive research on this group, there is still a gap in our understanding of their perceptions of ongoing strategic development processes and the structural conditions shaping these processes within HEIs [15,16]. For a greater comprehension of these individuals in accord with a novel strategic unfoldment in a university setting, this paper aims to explore middle management stakeholders’ perspectives concerning a mission-driven innovation university strategy by qualitatively combining a phenomenographic and thematic analysis for understanding the experiences of this exact group of individuals.

The body of literature on academic managers contains varying conceptualizations of this group of individuals, but as Bryman [17] presents through a systematic literature review of academic middle managers, they can be defined as individuals tasked with influencing and/or motivating others towards the accomplishment of departmental goals. It is also acknowledged that academic middle managers’ roles and responsibilities are universal, although contextual and geographical differences exist. Furthermore, as depicted by Rudhumbu [18], the narratives of academic middle managers gradually changed throughout the early 1980s into the late 1990s, which entailed transitioning from being agents of control and having high degrees of autonomy to being perceived as corporate agents with less autonomy. Individual roles and identities in academic management are often intertwined with political and personal complexities. However, this intersection has yet to be explored concerning the framework of mission-driven innovation in HEIs [8,9], which this paper investigates in the context of a novel conceptualization of mission-driven innovation [19] as experienced by middle management actors at a Danish university.

RQ: What is perceived by academic middle managers enacting a mission-driven strategy in a higher education institution regarding experiences, encountered challenges, and affordances?

Although middle management operates within a framework shaped by external policies at both the national and international levels [20,21], this paper does not delve into such policies. Nonetheless, we acknowledge the interconnectedness of these policies with the institutional-level processes examined herein and note their relevance in explaining the inclusion of an HEI strategy in the study. Middle management typically finds themselves in a challenging position, often described as being caught between their superiors and the staff they supervise [22]. This dynamic is particularly noteworthy in the context of HEIs, where middle management roles are often held by academics. While the prior literature has extensively explored the perceptions and experiences of academics in HEIs, this paper uses interviews with individuals in specific roles to focus on understanding and contextualizing the experiences, in particular the middle management, as it is yet to be explored in the case of the mission-driven innovation conceptualization in strategic developments at HEIs.

Therefore, this paper aims to contribute to a seemingly underexplored and complex area concerning mission-driven innovation and middle management leadership. The focus is examining the role of this exact group of individuals in the context of the mission-driven strategy transformation of the entire higher education institution and its academic staff into a mission-driven university. Transitioning comes with challenges, as highlighted by Al-Husseini et al. [23], and by seeking an element of innovation in the transformation, transformational leaders are key in the processes of transforming others. Through a qualitative approach, the remainder of this paper outlines an overview of mission-driven innovation in higher education institutions. It entails a representation of middle managers and academic middle managers as a basis for the analytical framing, and how the transition and transformation into a mission-driven university are currently experienced by academic middle managers. Perceptions concerning affordances [24] and challenges existing are presented to support future endeavors of a similar fashion, thereby contributing to further developments for HEIs in line with a mission-driven innovation framing and strategies for policy and strategic processes. It should be stressed that this paper examines the processes concerning the development and early stages in the implementation of the mission-driven innovation strategy, and therefore delimits from a full description and analysis of the effects of the strategy in focus.

2. Mission-Driven Innovation in Higher Education

Mission-oriented innovation in academic and higher education settings exhibits all the defining characteristics of mission-oriented innovation more broadly, but notably avoids political alignment when defining mission goals [11]. Contemporary issues in this context revolve around the intentions stemming from mission-driven and mission-oriented innovation policies. While a consensus has been reached among the senior leadership of most European HEIs through the 2030 Agenda [10], practical solutions and approaches for research institutions have yet to be fully developed, tested, and refined. A research-based exploration is crucial for understanding the implications of a mission-driven structure, particularly in terms of the impact of such a structure on decisions within HEIs and the opportunities and challenges that emerge [9,25,26].

The process of bridging research and practice within the framework of mission-driven innovation is what ultimately allows that innovation to manifest in real-world outcomes. When involving missions in the strategic visionary processes of HEIs, they can be perceived as a foundation and core of a university, as described by Özdem [27], since these missions include a set of goals that help the organization reach its aims and express its strategic goals. Furthermore, as Pucciarelli and Kaplan [1] derived from a SWOT analysis of managing complexities in HEIs, contemporary university strategies resemble trends from the commercial sector, combined with the notion of neglecting other stakeholders in purely academic publications published in top scientific journals. A central element emphasized by mission-driven innovation strategies for HEIs is the ability to include a vast myriad of stakeholders in the solving of missions, and the ability to collaborate across disciplinary and sectorial offsets. For the sake of mission-driven innovation processes to succeed, Adshead et al. [13] propose that common structures and transdisciplinary centres can help collaboration across research institutions and the private and public sector, in which a mission-driven innovation higher education framework is to become an intermediary for both internal and external institutional collaboration.

The literature on institutional collaboration highlights the benefits of interdisciplinary cooperation, including the development of innovative frameworks, enhanced creativity [28], and the pursuit of common goals through novel collaborations [29]. However, challenges exist, such as the underappreciation of the benefits of collaboration due to time constraints, tenure pressures, competitive tendencies, limited understanding of other disciplines, inflexible institutional structures, and inadequate support from management [30]. Mission-driven innovation is designed to support and streamline collaborative processes following the UNSDGs by formalizing a common framework for cross-institutional and cross-sectoral collaborations [8,25]. Given the novelty of mission-oriented innovation approaches in higher education, no standardized framework has been developed by supranational organizations for universities to apply. Nevertheless, universities are not strangers to the possibilities offered by the concept of mission-driven innovation, given that many routinely apply the UNSDGs in various educational activities, however, not concerning formal mission-driven university strategies [31,32,33,34].

3. Conceptualization of Middle Management Leadership

Middle managers, who are often described as intermediaries in organizational hierarchies, play a vital role within many institutions, including HEIs. Their responsibilities include mediating tensions between different levels of the organization, ensuring continuous operations, implementing strategic initiatives, and facilitating change [35]. However, defining the common characteristics of middle management roles is challenging due to significant differences between organizational contexts and the diverse definitions of middle management in the literature [36,37]. The strategic roles, motivations, aspirations, and relationships of middle managers have garnered research interest since the 1970s [38]. Previous studies have highlighted their position as intermediaries between senior management’s strategic goals and the local knowledge of frontline employees, a role that can extend to functioning as the arbiters of social order, such as in a Danish contemporary setting [39]. Middle managers also navigate complex power dynamics and politics while mediating interactions between upper management and employees, acting as a bridge between the strategic and operational levels of an organization. They wield significant influence but operate with varying degrees of autonomy, typically aligning with upper management’s decisions [28,40,41,42]. Birken et al. [40] identify four main activities associated with middle management: diffusing information, synthesizing information, mediating between strategy and day-to-day activities, and selling innovation implementation. These processes extend beyond organizational boundaries and include promoting strategic ideas and initiatives. Middle managers must be motivated and skilled in conveying strategies and inspiring their subordinates to execute them effectively. In some cases, they may even need to overcome both their own and their subordinates’ anxieties or resistance to adopt new ideas [43].

One defining aspect of middle managers’ roles is the competing interests that arise during times of change. Sense-making is a crucial component of middle managers’ responsibilities, as they must convey and coordinate decisions while maintaining a delicate balance in their relationship with subordinates; this process leaves some middle managers feeling inconsistent and untrustworthy [14,39]. De Boer et al. [44] highlight historical trends and paradigms in organizational and institutional structures that have shifted towards a more business-oriented and economically driven standard for middle managers; these patterns are seen in higher education as well as business. Based on this observation, the authors pose a pertinent question: “…what are the implications of these many substantial changes in what the contemporary university and its academic staff have become, and are still becoming, for the tasks of the academy’s middle managers?”

Academic Middle Managers in Higher Education Institutions

The question quoted above highlights the intricate complexities surrounding academic middle managers in HEIs. Universities have progressively adopted frameworks akin to those found in the corporate world, with demands for increased productivity stemming from political influences, primarily neo-liberalizing reforms, and New Public Management doctrines, seeping into the daily operations of universities [45,46]. Middle managers’ role in building bridges between upper management and employees, as it relates to translating policies into practice, has received relatively scant attention in HEI research [22], although this role is particularly noteworthy in the university context, where middle management leaders often hail from academic backgrounds and have extensive experience within academic structures [46].

Negotiating power dynamics while adhering to upper management directives and maintaining collegial relationships can pose significant challenges for academic middle managers, particularly as they often must also balance these responsibilities with their academic careers [46]. As described by Shuster [5], the key role academic middle managers play in implementing policies and strategies brings both positives and negatives to their academic lives. Their impact and role at the faculty and department levels have evolved from traditional core values, as seen in a Humboldtian university paradigm, to managerialism in the twentieth century. This shift is reflected in stricter requirements that are more dynamic and urgent, demanding the accommodation of labor market needs while placing middle management in the challenging positions of reconciling academic professionalism with employee needs and strategic economic realities [5].

Academic middle managers are also tasked with responding to the demand for innovation aligned with societal needs, a fundamental mission for universities. Innovative initiatives and ideas typically originate from upper management and are conveyed through specific organizational narratives [1,47,48]. Thornton et al. [46] highlight that middle management’s effectiveness in managing initiatives hinges on its ability to democratize decision making to a certain extent while remaining in control of time and budgets. Furthermore, over the past two decades, both American and European HEIs have increasingly relied on contingent and non-tenure-track appointments when hiring [5,49]. This trend, combined with the competitive nature of academia [50] and continuous pressure to publish [49], places significant external stress on academic staff under the purview of middle management, particularly when seeking to secure longer-term contracts, while at the same time, these staff members generally find themselves with significantly less funding than senior academics.

This plethora of social complexities within the daily working environments of HEIs also falls within the purview of middle managers’ responsibilities. Notably, De Boer et al. [44] highlight that these middle managers, such as academic deans in their example, are rarely adequately trained or experienced to handle the multifaceted demands associated with their positions.

4. Methods

A qualitative study was designed and conducted to capture the experiences and perspectives of middle managers in a specific academic context and to further contribute to the knowledge of academic middle managers in connection with a mission-driven innovation university strategy [51,52]. Qualitative research is well-suited to exploring subjective experiences, perceptions, and actions, making it appropriate for investigating the complex social processes involved in middle management leaders’ perceptions of mission-driven innovation in a university context [53,54,55].

The participants of the study include vice-deans, heads of studies, heads of departments, and researchers at the rank of associate professor or professor. Some of the individuals interviewed also serve as strategic counselors for the deans and rectorate. The participants represent three faculties: Humanities and Social Sciences, Engineering and Natural Sciences, and Technical and Information Technology. To ensure confidentiality, the entire dataset has been anonymized. Each participant provided informed consent, and approval for this research study was also obtained at the institutional faculty level.

4.1. Interview Format and Participant Background

The empirical data for this study were taken from 10 interviews conducted in the year 2023. They were conducted by the main author, and to ensure data integrity and mitigate the risk of technical issues, they were recorded on two recording devices. Only the main author was present as the main author is an early-career researcher who had limited pre-established relationships with most informants and held no leadership responsibilities. This approach ensured no interfering with or influencing the participants’ statements, and the authors felt this approach would reduce potential bias in the participants’ responses. The interview questions were designed to be open-ended, as it permitted the informants to go beyond the authors predetermined interests [16]. The transcripts of the interviews were fully anonymized to protect the identity of the informants, especially from colleagues. An overview of the participants’ roles at the university is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of informants.

Access to potential participants was arranged through email correspondence, and the selected participants reflected a balance between the risk of data saturation and the risk of excluding voices while having practical experiences with the positions of middle management leadership. Data saturation, as noted by Saunders et al. [56], occurs when the amount of data collected has reached a point at which no new understandings or insights can be obtained from additional data. However, it is important to be aware that data saturation can be subjective, and researchers should remain vigilant to ensure that valuable perspectives are not overlooked. Morse et al.’s [47] concept of gradually building a knowledge repertoire, which involves the process of achieving sufficiency or saturation regarding empirical material, was applied to the interview process in this study.

True anonymization of interview data is, as described by Saunders et al. [56], extremely difficult; guaranteeing complete anonymity to participants can be an ‘unachievable goal’ in qualitative research. All the participants discussed some information that posed a risk of traceability, though some expressed more concern about this than others. Our assurance that the data would be anonymized as fully as possible strengthened the informants’ trust and willingness to speak openly without concerns that they were representing themselves rather than the formal job position they held.

4.2. Data Analysis

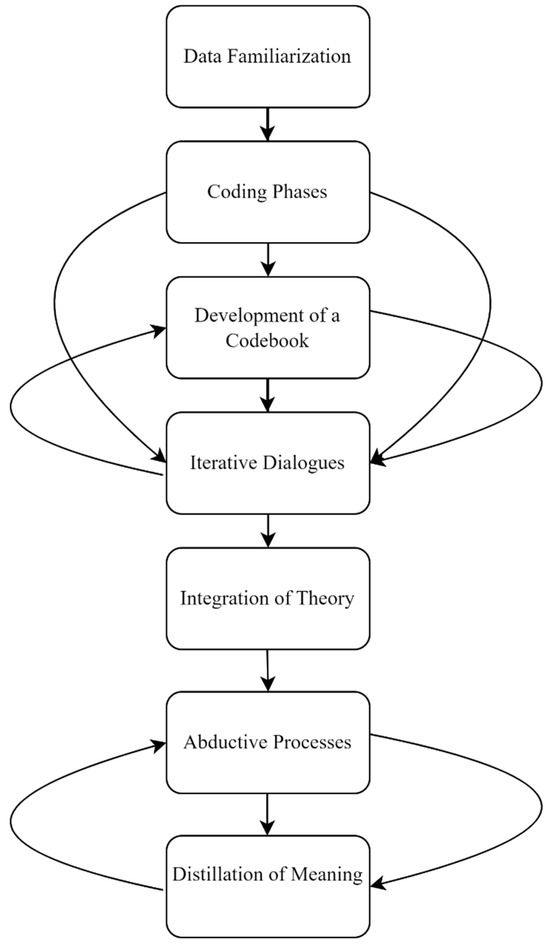

An overview of the process undertaken to analyze the interview transcripts is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the data analysis process.

Data Familiarization: Initially, a comprehensive re-read of interview transcripts was processed to deepen the understanding, and challenge preconceived notions, fostering opportunities for questioning existing perceptions and biases. Incrementally, open coding was applied to two transcripts by all authors, aligning common perceptions regarding possible categories for the later coding of the entire dataset.

Coding Phases: The coding processes involved two phases. The first, inductive, focused solely on the data without external theoretical input. The second, abductive, organized codes into predominant themes and discourses using the NVivo software version 14. In this phase, the authors applied two approaches: firstly, the main author coded each interview guided by the research question and the development of a codebook for keeping records and later sorting of relevance. A final pool of 76 codes was reduced to 39. This further led to the condensation of emergent themes. The dataset with codes and categories for possible themes was discussed and reiterated through dialogues between the authors. Herein, redundancy was attended to, removing the codes that either appeared three times or less and merging similar codes.

Development of a Codebook: To ensure and verify the data used for the inquiry into middle management perceptions on a current mission-driven strategy, errors, or deviating meanings, the codebook was refined to facilitate knowledge transfer and collaborative discussions, ensuring a shared understanding of the applied codes. Reiteration was crucial to ensure congruence between the methodological process and the research aim [57]. The categories developed by related codes were divided into themes, which were named after common perspectives from the collective codes, and further reduced from an initial five into three themes, resulting in commonalities among the group of individuals but also intricate differences among them, as proposed by Marton [58,59] and Han and Ellis [60]. The final iteration is exemplified in Table 2 with their related categories.

Table 2.

The three themes with their related categories.

Iterative Dialogues: Essentially, the iterative dimension occurred throughout both the coding phase and the following generation of the codebook. To ensure both reliability and validity for this study, two independent researchers, both previously having been or currently in middle managing contexts in higher education, assisted in checking codes and categories.

Preliminary to integrating theory and the following analysis, the clusters of codes related to the chosen themes were formed through iterative dialogues. Herein, the aim was to align clusters attributed with relevant codes into categories that would support the defining of themes. Each category formed was constructed with codes sorted through a 3-point scale: 2 = relevant, 1 = minor relevance, and 0 = no relevance for the established categories. This resulted in the exclusion of irrelevant codes and served as a boundary object for commonalities among author subjectivities.

By constructing the themes, and to a larger extent, dialectically acknowledging that bias and subjectivity in representations are two inseparable processes in these situations [53], the final constructs were checked to match the overall methodological procedures of both phenomenographic and thematic analyses. The final categories and their related themes are represented in Table 2. Herein, codes were not solely connected to a specific theme but could reoccur in different categories to different themes. Therefore, each thematic representation entails content from each related category, serving as the structure for the narrative and thematic unfolding in the Findings and Discussion Section.

Integration of Theory: The study’s narrative was enriched by integrating theory adapted to the context of strategic and management theoretical representation and applying a mediational and thematic analysis-inspired approach, influenced by scholars like Morrow and Brown [61] and Braun and Clarke [62]. Additionally, the analytical interpretations are construed based on an interpretive structuralist approach to social history (social and cultural reproduction). We furthermore applied the interpretive phenomenographic analytical procedures, presented by Han and Ellis [60], entailing the search being conducted iteratively, that foci are placed upon the commonalities of the studied individuals, and to not merely describe what the individuals mean but also nuances and differences among the individuals. It is, as proposed by Marton [58,59], the overall aim for phenomenographical studies to sort and categorize these meanings and experiences for uncovering the things in common as opposed to phenomenological studies emphasizing individual subjectiveness and experiences.

By transforming collective commonalities and differences into overarching themes constructed through coding and categorization, this study aims to contribute to a greater comprehension of intricate divergences and commonalities on the strategic unfoldment of a mission-driven innovation university strategy through the viewpoints of academic middle managers. It resulted in three processual steps: (1) applying qualitative coding processes to the empirical data, (2) a phenomenographic categorizing of codes, and (3) disseminating the findings of each theme in a narrative and thematic approach.

Overall, the purpose of applying certain theoretical lenses for interpreting how middle manager leaders have been navigating in and making decisions regarding the institutional strategy in play was to examine whether the prior literature pertains to the case of a mission-driven strategy administered by middle management and the constitution of the gaps of knowledge. Abductive processes were applied to achieve this, entailing novel and contextual central knowledge for HEIs and their academic middle manager. In addition, the gaps in the literature and potential knowledge to fill these were also of interest by demonstrating whether the mission-driven university strategy in focus can contribute with novelty to the field of management in HEIs. Certain points of interest emerged, which through the iterative deriving of meaning were put into different, albeit relevant in combination, theoretical contexts, serving the purpose of aligning contextual findings with the existing conceptualizations of relevance in a common narrative thematic representation [53].

Abductive Processes: The thematic narrative dimensions emerged from inductive processes but also involving, through a second round of condensation of meaning, theoretical deductive reflexion [63], reflecting the abductive nature of this study. Ensuring coherence for the analytical processes was facilitated by abductive logic and attention toward the precarity and tentativeness of living experiences [64]. By asking what might be, theoretical considerations influenced how the empirical contribution links with the examined practices and experiences derived. Subjectivities and researcher biases bear in combination a risk of trivializing the everyday practices studied if these hold a close resemblance to the researcher’s professional context. These can, however, be accounted for by ensuring and acknowledging knowledge production as dynamic and ever-changing and transparently presenting the scientific outset and methodological and analytical process applied [53].

Distillation of Meaning: Closely linked with the abductive process, two rounds of the condensation of meaning for the three chosen themes were discussed among the authors to identify the essence of the data for a nuanced understanding. Critical in qualitative inquiries is the alignment of theoretical points of reference, which predominantly are influenced by managemental theoretical considerations for this study. Transpiring from these were the final themes for reporting: academic middle managers’ understanding of a mission-driven innovation strategy, perceived barriers experienced by academic middle managers, and perceived affordances of a mission-driven innovation university strategy.

5. Findings and Discussion

The study did not begin with a predetermined theoretical agenda; rather, theoretical constructs were developed ad hoc based on the ongoing analytical process of conducting interviews and interpreting the participants’ statements. The interview data underwent two rounds of coding and categorization, a process aligned with the principles outlined by Braun and Clarke [62] and Lester et al. [65]. It is worth noting that the themes identified in this study are thus not the product of theoretical agendas operationalized into testable hypotheses through a specific methodological approach. Instead, they emerged through a dynamic interplay between methodology and theory, as described by Brinkmann [53].

The following sections are structured thematically in response to the posed research question: what is perceived by academic middle managers enacting a mission-driven strategy in a higher education institution regarding experiences, encountered challenges, and affordances, presenting three analytical themes. Extracts are presented anonymously and are intended to illustrate the experiences and perceptions broadly shared among academic middle managers at a Danish university. Following an abductive inquiry, the authors followed an iterative theory-driven approach, from which three dominant themes of analytical interest emerge: academic middle managers’ understanding of a mission-driven innovation strategy, perceived barriers experienced by academic middle managers, and perceived affordances for a mission-driven innovation university strategy. The sections below combine a descriptive thematic approach with an interpretation of selected excerpts from the interview transcripts.

5.1. Academic Middle Managers’ Understanding of a Mission-Driven Innovation Strategy

The interview participants indicated that since a mission-oriented innovation strategy is developed, leadership must establish its legitimacy and convince a wide range of academic staff members of its utility and relevance. This finding aligns with prior research, such as Boon and Edler’s [6] observations of the increasing alignment of innovation policies with supranational organizations and the subsequent adherence to these decisions. At the time of writing, the Danish university that served as the context for our study is still in the process of implementing mission-driven innovation throughout the institution. The participants view this implementation as an institutional process initiated with specific strategic and operational goals (e.g., common funding applications and improving collaboration), and is designed to develop common processes for the university’s various research groups to follow:

“This transformation, well, I think the difference, from my perspective, is that we’re moving on two legs. But I believe it’s happening both in the EU and in Danish foundations. In the past, there was a heavy focus on the traditional basic research leg. And now, I think this is an expression of us placing just as much weight on the other leg, which is also about the mission-oriented aspect. I think they both have validity, and what we need to figure out is when they overlap, when there are synergies. I think we need to understand if it’s two separate legs or more of a unified leg, but I believe it’s a process we must gradually get into.”—A

“It’s like there’s something that ties it all together, especially with the missions. It becomes evident when a mission falls within this, that’s where we sort of place things, right? It becomes clearer and more transparent in some way, doesn’t it?”—D

It is, as Al-Husseini et al. [23] describe, also greatly dependent on the individuals involved in the transformative processes. He further argues, which can be linked to the case of the Danish University, that these strategic endeavors are more likely to succeed if the leadership responsibilities become distributed throughout the organization. Middle management has focused on two primary goals in this process to date: first, alignment with the board of directors and upper management, and second, the promotion of the content and goals of the strategy among the academic staff. The latter can be seen as a form of internal branding [66] aimed at fostering attachment and identification with the brand is represented by mission-driven innovation. As mentioned by several informants, universities, in a modern entrepreneurial paradigm, must compete for visibility and funding opportunities, which a mission-driven innovation strategy potentially signals. Academic middle managers perceive this both as beneficial to individual researchers’ profiles but also as part of the institution’s overall profile:

“It’s also about how we position ourselves in the best way regarding what has largely been a research need in connection with climate loan realization. How do we position ourselves best in relation to that? Well, it might be by engaging in co-creation with central stakeholders and offering our insights on a part of this.”—G

“It’s interesting to frame this as addressing significant challenges, a means to profile oneself for those entering to make a difference in the world. It’s not just conducting research; it’s about contributing to solving society’s major problems. It’s an extension of my focus, starting with the interdisciplinary aspect. Then, ‘How do you turn it around?’ Is this a possible approach? It’s somewhat an opportunity [the university] is trying out in practice.”—D

The academic middle managers tended to perceive their contribution to the implementation of mission-driven innovation strategy as either a subjective (non-formal) or a professional role, although they often perceived these as interchangeable. Most informants, if not all, agreed with the formal institutional expectations and purposes of becoming mission-driven, but simultaneously deviated by assimilating their daily routines and social life in the institution with a subjective perception. The informants most often depicted the strategic scenario that was unfolding at the time of the interview as a potential scenario since strategies constitute visions for the future:

“Yes, we should remember that the strategy is a strategy for something that hasn’t happened yet. So, there’s a question behind it as well: what do we do in this area? We’re doing some things that, in my view, might have some components of what you could call mission-driven. But otherwise, it’s something new we’re initiating.”—G

“Many leaders, including myself, sit on various boards. This sparks interest [red. a mission-driven innovation university strategy], and, I’m just saying, when we talk about what organizations should try at the university…”—F

The element of novelty is important, as established familiarity and internal organizational support are perceived as crucial among all informants; however, perceptions differ based on whether the middle manager views the strategic development process from a managerial perspective with branding in focus or as an academic. This becomes especially apparent when former experiences are drawn upon:

“The concept of missions is starting to wear thin. It’s used for many different things, which makes it somewhat complex. There are many different understandings it’s built upon, and things are built on those different understandings. It’s about how you bring it all together, right?”—G

“But if we’re going all the way, it’s not enough to just talk to the researchers around the faculties and departments. We actually need the entire university to be willing to accept that this requires, structurally, culturally, and financially, acknowledging that if we’re going to get there, it’s an investment.”—A

As former or current academics, they are accustomed to the institutional structures of HEIs, and share the experience of similar processes prior to their current roles involving leadership and management responsibilities. Several interviewees made statements that highlight that as a crucial aspect of academic middle managers in their daily framing of institutional narratives, a task which they perceive through their dual roles of academics and academic middle managers. Their thoughts concerning the existing structural conditions set forth by the mission-driven strategy are not spared this duality:

“It’s also interesting to see if it really becomes that. I can imagine that there will be a few clusters where it works, and that would be good at least. The question is, what about the rest? Do these clusters soak up all the funding, and the rest dries up?”—I

“We are very bound to deliver projects, applications that can generate revenue, etc., on a short-term basis. There is not enough time to do the work required to make it a sustainable configuration. It’s a general threat to the entire university’s business.”—A

Striking a balance between financial deliverables, such as project funding, and ensuring collective support and recognition can delay or prevent the implementation of new strategies, and the academic middle managers in this study acknowledged the reality of uneven opportunities for research groups wishing to construct research projects in a mission-driven manner. This intricacy is often difficult in HEIs, also in the Danish context, as the distributed autonomy of individual faculties and departments simultaneously promotes freedom while requiring the upholding of overarching institutional goals—wherein academic middle managers are perceived as guiding intermediaries.

5.2. Perceived Barriers Experienced by Academic Middle Managers

Contemporary universities typically exhibit four traits relating to institutionalization, but with significant variation between institutions, as described by [67]. Two traits concern the role of the university in educating students, one concerns the pursuit of clusters of disciplinarity, and the fourth entails that universities enjoy some form of institutional autonomy as far as their intellectual activities are concerned [67]. Despite this autonomy, adherence to national and supranational policies affects HEIs’ strategic development, which is a predominant factor in the calls and initiatives related to the UNSDGs from which the mission-driven innovation concept originated. The implementation of strategies in HEIs was described by the informants as a delicate balancing act. Gaining support from various departments and faculties within academic settings involves both implicit and explicit negotiations of influence and perceived relevance [20], which the informants often deemed as crucial:

“I experience a timing where everyone needs to get onboard, so we don’t encounter resistance. So, it’s not like we’re forcing their arm behind their back and compelling them in this direction.”—C

“If we don’t establish some kind of common culture, we’ll never achieve any other form of collaboration. We’ll end up with sporadic cooperation.”—J

The process of establishing support is influenced by institutional routines, norms, and cultures, as well as structural factors, such as the constant quest for funding and disciplinary positioning. Additionally, institutional decisions made by middle management continually affect these dynamics. In essence, a strategy’s implementation is shaped by a complex interplay of factors within the university’s ecosystem, making it a multifaceted and evolving process. Some informants highlighted the emergent possibilities and challenges for collaboration between faculties and departments which a new strategy creates:

“Today, it would be very challenging because each institute has its own rules and staff. There’s the issue of ‘different ships sailing,’ where some institutes are not performing well. I’d rather not depend on them in case something goes wrong. There are too many super-optimization strategies within the individual institutes.”—A

“It was only after the introduction of New Public Management that there was a shift towards centralization and concern for it. We were quite content before. Finances were determined at the faculty and rectorate levels, not individual positions, salaries, or expenses. Now, everything has been decentralized, down to each research group, resulting in micro-management of everything.”—B

Academic middle managers hold a crucial role in shaping institutional strategies, and their actions are driven by strategic ideals. These ideals, which can vary in scope and context, are essential for setting the institution’s direction toward an envisioned excellence [68]. Ideals are integral to the strategic narratives that guide administrative processes within institutions. The academic middle managers we interviewed see mission-driven innovation as serving dual purposes at their institution. Additionally, it is important to recognize that HEIs tend to function both collectively and independently, which emphasizes the significance of effective communication and the alignment of strategic ideals to ensure the successful implementation of institutional strategies:

“It’s more about how we actually create opportunities and conditions and understandings for each other so we can collaborate. Because, yes, it’s fine that we could adopt another framework to make us collaborate… It’s somewhat secondary in my view. Why haven’t we done it already? I know there are occasional elements of collaboration, but it’s often sporadic and short-lived.”—J

“It’s clear that a focus on missions, which drains resources from others, and on the other hand, these cutbacks, it does create problems. I assume, at least from what I know, that leadership at various levels is aware of it and attentive to it.”—I

Time was often referred to as an important factor for strategic endeavors. The participants noted that establishing support among the academic staff requires a delicate balance (in terms of both time and power). A recurring theme in the interviews with the academic middle managers pertained to the ever-changing and busy nature of academia, where time is of the essence, which prevents the academic staff from engaging in preliminary common efforts. The limits placed on the pace of change by these structural constraints are sometimes incompatible with the scope and speed of the strategic change expected by university leaders:

“It’s actually quite a significant facilitation to get people, who are also busy in their daily lives, to contribute and allocate time continuously for some of these processes, which can feel a bit slow because they involve leadership processes where we’re trying to find a common direction. And that takes a long time.”—C

“But if you really want to launch such a large and heavy system, it won’t help if you think you’ve solved it in five years. And the energy situation is certainly not solved at all in five years. So, the idea that they follow that kind of crater, that it should be time-limited, well, that might be a bit challenging.”—J

The informants noted that their role in bridging the gap between the upper and lower levels of the institution was impacted significantly by their perceptions of the strategy being implemented and its relationship to the role of universities more broadly. The implementation of mission-driven innovation as a concrete strategic decision guarantees neither a smooth transition nor support among the academic staff. Balancing adherence to established goals with overcoming internal resistance is a delicate process, and moving forward with the mission-driven approach presents challenges for both middle managers and the structural institutional conditions in place, both at the organizational and departmental levels.

“I think people on the management side are well aware of what they’re saying. It’s very much an overarching strategy. So, I will be damned if what’s happening is going to be good, but there don’t appear to be any consequences [red. if it fails] from what I understand.”—B

“And you have to keep in mind that it should be a combination of something top-down and bottom-up. Top-down because sometimes there is a need to set some boundaries, but bottom-up because people meet best by themselves. People meet best by themselves, but at the same time, they need to be part of it. It’s part of what keeps us going. But it’s simply extremely important.”—H

The successful implementation of mission-driven innovation at the Danish university relies heavily on coherence among peers at the departmental level. Each department has its own culture and norms, and collaboration across disciplines and with external companies and institutions is essential for mission-driven innovation projects. However, not all academic middle management leaders necessarily ground their statements on this topic in formal strategic descriptions or marketization prospects. This may be due to a lack of clarity about the reasons behind the strategy or the tensions that can arise among colleagues [46]:

“As I understand it, the strategy is intended to be rolled out across all faculties. But what you’re saying there is a bit like, it might be the idea, but it’s not certain it will become reality. It’s this lighthouse system, which I feel we’ve tried and worked with for many years. And I don’t have good experiences from those lighthouse projects.”—A

“They speak different terminologies, they have different understandings of what a method is, they have different methods. For example, is there enough respect for each other? It plays a role in how much respect and trust you have for each other. How much are you able to understand another field’s standpoint and approach, etc.? Are you willing to immerse yourself in it?”—I

The informants noted that this collaborative dimension varies in terms of the affordances it provides for both the institution and individual researchers. It was repeatedly stated in the interviews that for any strategy to be fully internalized within an institution, time and effective communication are crucial for gaining the support of employees:

“So, communication is a big problem. And you know our case communication is very problematic because of all this with different nationalities also.”—E

“Let me start elsewhere by saying that I don’t believe the dissemination of this strategy and these ideas have been very successful. We’ve had approximately one meeting per institute per campus for introduction. However, our dean and pro-dean for research spoke for about two times fifteen minutes, and then we were asked for our input on mission-based research projects. I had a proposal, as did a few others. I spent about a day working on it collectively. So, in my experience, it hasn’t been properly introduced.”—A

Beyond gaining institutional support among the academic staff, it is also important to convince academic middle managers. The participants explained that the effectiveness with which strategic changes are communicated from upper management to academic middle managers can be affected, positively and negatively, by how the organizational structure for communication and perceived governance aligns with the presented proposals.

5.3. Perceived Affordances of a Mission-Driven Innovation University Strategy

The incorporation of mission-driven innovation in the current university strategy, focused on addressing the UNSDGs, is a novel and complex endeavor that brings both potential benefits and risks. Similar findings by Adshead et al. [13] support the concerns raised by the informants, which revolve around the possibility that a mission-driven innovation approach could result in the institution adhering to predetermined objectives that are too fixed to allow for flexible collaboration with stakeholders. Moreover, there is the challenge of reconciling the demands of this approach with the intricate politics within HEIs, which may not always align with the ambitions of individual universities [6]; instead, as proposed by an informant, mission-driven innovation requires establishing an institutional movement and common purpose:

“We need to create a movement where some environments, instead of diverging, collaborate more. That’s something I see in the way it’s presented. The idea is that missions should support interdisciplinary and cross-faculty collaboration, aiming for major EU grants.”—A

“It’s essential to understand and recognize that people have different perspectives and approaches within their fields. While we may disagree, there’s value in understanding each other’s viewpoints and expertise. When these intersect and overlap, there’s potential for something significant to happen. If this concept becomes formally integrated into our university, it could benefit researchers, students, and external observers who see its value.”—D

While views on the affordances created by mission-driven innovation were broadly shared by our participants, opinions varied regarding the optimal approaches to achieving them. These differences highlight the complexity of implementing mission-driven innovation and the need for flexibility in addressing various challenges and opportunities within HEIs. The impacts of a mission-driven innovation approach on research and common funding and collaboration opportunities are also perceived as meaningful, particularly concerning cooperation among disciplines and research groups. A common framework potentially creates a common pathway for such cooperation and allows for it to become more frequent and consistent:

“I advocate for leveraging each other’s strengths across various research groups and institutes within our organization. This is particularly relevant with the mission-based approach, where we aim to extract and leverage synergies to achieve more collectively than individually.”—A

“I remember that the sustainability goals were supposed to be like that, and it met significant resistance within the organization, where researchers were saying, ‘Can’t you just try some other sustainability goal? And can’t I be here if I don’t think I fit the sustainability goals or something like that?’ So, in that case, it is a different strategy. Maybe [red. upper-management] have been sitting and thinking, and looked down, oops, we must do something different.”—D

The structural conditions at the university previously included initiatives for cross-faculty collaboration. However, the informants in this study generally perceived these initiatives as inefficient and sporadic. While academic middle managers have made efforts in the past to facilitate greater interaction among faculties and researchers, the proposal of a mission-driven innovation strategy represents a different approach. Some informants saw their role as academic middle managers as crucial in mediating information between the academic staff and upper management to help overcome these barriers and promote collaboration:

“To succeed with this strategy, broad support and ownership within the organization are crucial, which is something we continually strive for. It’s common for individuals to have their comfort zones, areas of expertise, and routines. Introducing change can cause uncertainty. Leadership plays a vital role in establishing security, allowing individuals to expand their horizons and stay motivated. It’s not just a barrier; it’s a leadership challenge.”—F

“I think the executive board and the rectorate have succeeded in taking ownership of the leadership in this. Where I am, at least, I see it. In my department, I see that the leadership personnel are aligned with it, and we are likely to succeed with it. I think that’s very important. I have a suggestion for how I can work into it myself. It’s also an expression of an evolving system.”—H

The participants indicated that they perceive their role of advocating for mission-driven innovation strategies differently depending on whether support and recognition have been achieved or whether institutional ownership is present or lacking. This furthermore ties into the challenges of conveying strategic desires while acknowledging the structural conditions in place for the academic staff, which some academic middle managers highlighted as a major task for those with leadership responsibilities:

“I don’t sense that anyone finds this difficult, annoying, or unhelpful, but it may be due to the stage we’re at. People may not have realized it yet, so I don’t see it as a barrier. While some researchers might think it’s not for them, we’re not implementing the strategy in a way that dictates ‘everyone, this way.”—C

“Leadership-wise, I actually see my tasks as … and supporting people in understanding that these are opportunities. Of course, these are opportunities that are coming.”—H

The evidence indicates that without a cohesive shared understanding among the academic staff, a defining element preventing support and action is the fear of the unknown. Even if an academic middle manager acknowledges the branding value of a strategic decision, negative experience of strategic initiatives can color their and their subordinates’ perspectives:

“I mean, I think that the whole interdisciplinary aspect of it is good, and we’ve been practicing it here at the university since the mid-70s. But I don’t get the impression that there’s anyone interested in how we’ve done it.”—B

“The significant difference is, of course, that we have evolved to be mission-driven, but it’s also clearly a stepping stone from the previous strategic period from 2015 to 2021. For example, practicing interdisciplinary projects has been advantageous. It’s a huge advantage that we now have that experience where we are.”—F

“So, the initiatives that we’ve set on this path should continue to operate as it always has. Yes, because it’s a bit like what we just mentioned a bit earlier, that it’s not necessarily so different from previous practices.”—H

The emphasis placed on looking backward is also perceived by the informants as what is potentially missing in the current university strategy. Drawing upon prior experiments and internalized (albeit tacit) knowledge accumulated throughout the life of the university could lead to valuable and concrete insights, which might benefit the initiatives concerning inter- or transdisciplinary collaborations in research—aligning with the common perceptions of missions and mission projects [9,69].

6. Practical Implications and Concluding Remarks

Academic middle managers hold pivotal roles in bridging strategic objectives and operational realities. They mediate the complexities of aligning external demands, such as mission-driven innovation and the UNSDGs, with internal conditions while navigating academic culture and power dynamics. Achieving support for mission-driven innovation necessitates fostering cross-departmental collaboration, the awareness of the current institutional conditions, and maintaining a delicate balance between granting autonomy and ensuring alignment with broader strategic objectives [67]. It is imperative for HEIs to recognize that idealized strategic visions must be tailored to the organizational context, and this demands a keen understanding of academic staff perspectives and institutional structural conditions. Academic middle managers thus serve as critical bridge-builders, promoting the internalization of strategic visions, and navigating this terrain requires astute leadership and engagement with stakeholders across departments and faculties.

For the future endeavors of HEIs, either initiating or amid designing mission-driven innovation institutional strategies, we propose that academic middle managers involved in strategic processes, similar or identical to mission-driven innovation, consider the following:

Encouraging cross-faculty, interdisciplinary, and industry collaborations that align with agreed-upon routines and practices while ensuring functional structural conditions related to mission-driven innovation proposals.

Our findings support the call for increasing the degree of and improving institutional collaborations both internally among disciplines and departments and externally with stakeholders outside the university. Especially, there is a need for common practices and cultures following a mission-driven innovation transition, as novel strategies can require the re-thinking of prior procedures for research. A key point is to draw upon prior experiments, initiatives, and common procedures for research, whether they were successful or not, as learning can transpire from each prior attempt.

Holistically and transparently addressing concerns, preliminary initiatives, and strategic outcomes among the academic staff concerning the mission-driven innovation strategic framework.

Good intentions are the primary offset for the incorporation of a mission-driven innovation strategy, but it has shortcomings when communication is perceived insufficient by academic middle managers. Signs stemming from the interviews point towards the need for making additional voices heard for the strategy to be perceived as meaningful by both the academic middle manager leadership and the academic staff they manage.

Developing routines that balance strategic decisions and the dispersed autonomy of research groups, while conveying meaningful opportunities that emerge from mission-driven innovation across all institutional levels.

A core function of academic middle management leaders is to administer directions set and ensure that decisions from the top management are fulfilled throughout the organization, which our findings depict as a critical, and often challenging process to maneuver in. This becomes evident when the academic middle managers resist the narrative proposed by the top-management, indicating a greater need for ensuring individual commitment as a precondition for success, as experienced with the mission-driven innovation strategy.

An interesting reflection, but not the focus of this study, is whether the researchers or the academic middle managers for this study also are involved with UNSDG-related activities, which would potentially provide them with concrete and practical experiences for the further development of the mission-driven strategy. It is also a final advice, based on the findings of this study, to ensure that there is room for navigating the managerial complexities, falling under the responsibility of this group of leaders, through continuous dialogue and collaboration among and within the group of leaders, the heads of research and or education, and the academic staff. The informants for this study, if sharing one commonality, all perceive communication as crucial for the advocacy and support of strategic decision-making processes concerning the institution.

7. Limitations and Future Perspectives

As this study examines the experiences and perspectives of academic middle managers as they relate to the current mission-driven innovation strategy at a Danish university, there are limitations present in terms of contextual transferability, researchers’ subjectivities, and types of informants. Since mission-driven innovation strategies in higher education contexts are scarce, although missions as a buzzword are no novelty for the Danish university in focus, it will entail navigating strategic uncertainty. Therefore, this study may be limited in terms of whether the findings can apply to HEIs that operate differently concerning the experiences of academic middle managers as a broad and diverse group of leaders [46]. Conducting qualitative research both iteratively and abductively also raises certain questions concerning theoretical considerations. It involves multiple interplaying and interpreting subjectivities, which affects theoretical choices, thematic constructions, and analytical lenses, allowing potential differences to influence the analytical and theoretical constructions [53]. The authors of this study considered and attempted to control for this variance throughout the process, but future similar studies may potentially differ in their empirical interpretations. Limitations also exist related to the chosen group of participants, which here deliberately excluded upper management and academic staff. Furthermore, the contextual setting of a Danish university differs from HEIs in other contexts, which are subject to different political processes. This study focused on highlighting a specific group of leaders, who have already been found to be in delicate positions [22,43], for a deeper understanding of the experience of mission-driven innovation at the university, the possible implications, and how the academic middle managers perceive the strategic possibilities and turmoil they experience. We, therefore, emphasize that our findings are to be perceived as situated knowledge, and dissimilar contexts could generate different perceptions among academic middle managers.

Despite these limitations, this study offers valuable insights for future endeavors in mission-driven innovation within HEIs. It highlights the importance of addressing not only the challenges and potential benefits of such innovation but also the need to overcome academic resistance to change to ensure support for overarching institutional strategies. Mission-driven innovation, as experienced at the studied Danish university, serves as an example of how universities can contribute to addressing global challenges such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. While it faces obstacles, partially due to its conceptual novelty in HEIs [8,9,13], this case provides valuable insights for similar organizations and academic middle managers looking to implement mission-driven innovation.

Future studies examining mission-driven innovation in higher education contexts or academic middle managers’ role in and perception of strategic processes should maintain awareness of institutional conditions, such as existing cultures, routines, and collaborative practices. They should also recognize that strategies serve the dual purposes of branding and setting institutional ideals. Within this context, academic middle managers must navigate between adherence to institutional and external political processes and may not take a positive view of the affordances of practical strategic outcomes if these are not aligned with the institutional reality. We propose a greater understanding of these through a comparison of universities’ strategic approaches to missions (preferably aligned with the conceptualization of mission-driven innovation) and national and supranational policies for uncovering commonalities across geographical and cultural contexts. Mapping processes concerning the role of academic middle managers and common traits in defining and designing missions or institutional conditions can potentially support and strengthen the preliminary processes of future strategic initiatives for HEIs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.C., X.D. and A.O.P.d.C.G.; methodology, S.H.C., X.D. and A.O.P.d.C.G.; software, S.H.C.; validation, S.H.C., X.D. and A.O.P.d.C.G.; formal analysis, S.H.C.; investigation, S.H: Christiansen; resources, S.H.C., X.D. and A.O.P.d.C.G.; data curation, S.H.C., X.D. and A.O.P.d.C.G.; writing—original draft, S.H.C.; writing—review and editing, S.H.C., X.D. and A.O.P.d.C.G.; visualization S.H.C., X.D. and A.O.P.d.C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines for Aalborg University, Denmark, approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Department of Planning and Sustainability (Approved March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to (due to agreements of anonymity to informants for this study).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Pucciarelli, F.; Kaplan, A. Competition and strategy in higher education: Managing complexity and uncertainty. Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondo-Brovetto, P.; Saliterer, I. (Eds.) The University as a Business? VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnucci, L.; Spigarelli, F. The Third Mission of the university: A systematic literature review on potentials and constraints. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 161, 120284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Kirby, D.; Urbano, D. A Literature Review on Entrepreneurial Universities: An Institutional Approach; Autonomous University of Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, J.H. The New University: What It Portends for the Academic Profession and Their ‘Managers’. In The Changing Dynamics of Higher Education Middle Management; Meek, V.L., Goedegebuure, L., Santiago, R., Carvalho, T., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 33, pp. 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, W.; Edler, J. Demand, challenges, and innovation. Making sense of new trends in innovation policy. Sci. Public Policy 2018, 45, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Urbano, D.; Fayolle, A.; Klofsten, M.; Mian, S. Entrepreneurial universities: Emerging models in the new social and economic landscape. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 47, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. Mission-oriented innovation policies: Challenges and opportunities. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2018, 27, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy—Challenges and Opportunities; UCL: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The United Nations. Global Sustainable Development Report; The UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- EUA—European University Association. Universities and Sustainable Development—Towards the Global Goals; EUA: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission; Directorate General for Research and Innovation. Governing Missions in the European Union; Publications Office: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/618697 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Adshead, D.; Akay, H.; Duwig, C.; Eriksson, E.; Höjer, M.; Larsdotter, K.; Svenfelt, Å.; Vinuesa, R.; Fuso Nerini, F. A mission-driven approach for converting research into climate action. npj Clim. Action 2023, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canhilal, S.K.; Lepori, B.; Seeber, M. Decision-Making Power and Institutional Logic in Higher Education Institutions: A Comparative Analysis of European Universities. In Research in the Sociology of Organizations; Pinheiro, R., Geschwind, L., Ramirez, F.O., VrangbÆk, K., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2016; Volume 45, pp. 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdzir, M.N.; Ghani, R.A.; Yazid, Z. Faced with Obstacles and Uncertainty: A Thematic Review of Middle Managers in Higher Education. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2022, 7, e01129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehbock, S.K. Academic leadership: Challenges and opportunities for leaders and leadership development in higher education. In Modern Day Challenges in Academia; Antoniadou, M., Crowder, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Effective leadership in higher education: A literature review. Stud. High. Educ. 2007, 32, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudhumbu, N. Managing Curriculum Change from the Middle: How Academic Middle Managers Enact Their Role in Higher Education. Int. J. High. Educ. 2015, 4, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Think tank DEA. How Can Missions Become Successful?—A Literature Review on Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy; DEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Humes, W.; Bryce, T. Post-structuralism and policy research in education. J. Educ. Policy 2003, 18, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, D.P. The Politics of Higher Education. Daedalus 1975, 104, 128–147. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Deneen, C. ‘Sandwiched’ or ‘filtering’: Middle leaders’ agency in innovation enactment. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2020, 42, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Husseini, S.; Moizer, I.E.B.J. Transformational leadership and innovation: The mediating role of knowledge sharing amongst higher education faculty. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 24, 670–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcgrenere, J.; Ho, W. Affordances: Clarifying and Evolving a Concep. In Proceedings of the Graphics Interface 2000 Conference, Montréal, QC, Canada, 15–17 May 2000; p. 186. [Google Scholar]

- EUA—European University Association. Universities without Walls—A Vision for 2030; EUA: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scown, M.W.; Winkler, K.J.; Nicholas, K.A. Aligning research with policy and practice for sustainable agricultural land systems in Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4911–4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güven, Ö. An Analysis of the Mission and Vision Statements on the Strategic Plans of Higher Education Institutions. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2011, 11, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar]

- Medved, P.; Ursic, M. The Benefits of University Collaboration within University-Community Partnerships in Europe. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 2021, 25, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Coombe, L. Models of interuniversity collaboration in higher education—How do their features act as barriers and enablers to sustainability? Tert. Educ. Manag. 2015, 21, 328–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, S.H.; Juebei, C.; Xiangyun, D. Cross-institutional collaboration in engineering education—A systematic review study. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2023, 48, 1102–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beagon, U.; Kövesi, K.; Tabas, B.; Nørgaard, B.; Lehtinen, R.; Bowe, B.; Gillet, C.; Spliid, C.M. Preparing engineering students for the challenges of the SDGs: What competences are required? Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2022, 48, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jardali, F.; Ataya, N.; Fadlallah, R. Changing roles of universities in the era of SDGs: Rising up to the global challenge through institutionalising partnerships with governments and communities. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neary, J.; Osborne, M. University engagement in achieving sustainable development goals: A synthesis of case studies from the SUEUAA study. Aust. J. Adult Learn. 2018, 58, 336–364. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, W.M.; Henriksen, H.; Spengler, J.D. Universities as the engine of transformational sustainability toward delivering the sustainable development goals: “Living labs” for sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 1343–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, B.; Floyd, S.W. The strategy process, middle management involvement, and organizational performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 1990, 11, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, S.; McAuley, J. Conceptualising Middle Management in Higher Education: A multifaceted discourse. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2005, 27, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H. Strategy Implementation: The Impact of Demographic Characteristics on the Level of Support Received by Middle Managers. MIR Manag. Int. Rev. 2005, 45, 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, B.; Schmid, T.; Floyd, S.W. The Middle Management Perspective on Strategy Process: Contributions, Synthesis, and Future Research. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 1190–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, M.; Stensaker, I. The challenges of middle management change agents: How interactionism can provide a way forward. J. Change Manag. 2011, 11, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birken, S.A.; Lee, S.-Y.D.; Weiner, B.J. Uncovering middle managers’ role in healthcare innovation implementation. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, M. Leadership theory: Past, present and future. Team Perform. Manag. Int. J. 1997, 3, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, B.; McVitty, D. Finding the Humanity in Higher Education Leadership; Minerva & Wonkhe: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, N.; Lee, H.; Ford, J. Who is ‘the middle manager’? Hum. Relat. 2014, 67, 1213–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, H.; Goedegebuure, L.; Meek, V.L. The Changing Nature of Academic Middle Management: A Framework for Analysis. In The Changing Dynamics of Higher Education Middle Management; Meek, V.L., Goedegebuure, L., Santiago, R., Carvalho, T., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 33, pp. 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, M. Knowledge, Politics, and Commerce: Science Under the Pressure of Practice. In Science in the Context of Application; Carrier, M., Nordmann, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 274, pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, K.; Walton, J.; Wilson, M.; Jones, L. Middle leadership roles in universities: Holy Grail or poisoned chalice. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2018, 40, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.Y.; Guerra, A.; Chen, J.B.; Lindsay, E.; Nørgaard, B. Exploring Academic Middle Leaders’ Viewpoints on Supporting Change in Higher Education Institutions Using Q Methodology—A case in Poland. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh 2023, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, N.; Griffith, A.I. Talk, texts, and educational action: An institutional ethnography of policy in practice. Camb. J. Educ. 2009, 39, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak-Aydemir, N.; Gleibs, I.H. A social-psychological examination of academic precarity as an organizational practice and subjective experience. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 62, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Brink, M.; Benschop, Y. Gender practices in the construction of academic excellence: Sheep with five legs. Organization 2012, 19, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluhm, D.J.; Harman, W.; Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R. Qualitative Research in Management: A Decade of Progress: Qualitative Research in Management. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1866–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummesson, E. Qualitative research in management: Addressing complexity, context and persona. Manag. Decis. 2006, 44, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, S. Qualitative interviews. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Discourse and Text: Linguistic and Intertextual Analysis within Discourse Analysis. Discourse Soc. 1992, 3, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 6th ed.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. Qualitative Significance. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 151–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]