Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a sudden shift to virtual platforms. Physical distance and limited experience with both synchronous and asynchronous teamwork at work and school hampered problem-solving and the development of critical thinking skills. Under these circumstances, the implementation of team-based and problem-based learning (TBL, PBL, respectively) required a reevaluation of how teams collaborate and engage in problem-solving remotely. The research team conducted a systematic review to identify health services studies, themes, and attributes of learning initiatives associated with the success of TBL and PBL conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. This systematic review was conducted using the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The review results identified three themes associated with TBL and PBL learning initiatives in health services: (1) TBL and PBL have transformed health services education with modified TBL (mTBL) and modified PBL (mPBL) as the new norms; (2) the amplification of age-appropriate principles for professional motivation in healthcare; and (3) active learning impacts practical abilities for professional success and future leadership roles. The pandemic underscored the importance of flexibility, resilience, and innovation in TBL and PBL approaches in health services education. Despite the superiority of mPBL and mTBL, the barriers to implementation and student acceptance of active learning include inadequate resource and space allocation, and student preferences for passive, traditional lecture. Further, online learning required increased facilitator training, administration time, and time to provide feedback.

1. Introduction

1.1. Team-Based Learning

Teamwork has been identified as one of the primary skills required in the global workplace [1]. Further, the need for interdisciplinary teamwork in effective health services is well established [2]. Traditional team-based learning (TBL) includes consistent groups, student accountability, activities with immediate feedback, individual and team readiness assessments, and a team-based problem or project [3]. A qualitative study of TBL in a nursing student population validated themes similar to the traditional TBL approach, such as readiness for learning and collaboration, and identified students’ difficulties navigating team roles and the high volume of content [4]. An experimental quantitative study of undergraduate nursing students demonstrated the superiority of TBL, compared to traditional lecture (TL), in the teaching of community understanding and assessment, and suggests a trend in overall higher scores for TBL vs. TL. Similar experimental quantitative studies with a larger sample size are needed in health services education [5]. More broadly, graduate medical education (GME) was challenged during COVID-19. A quantitative study comparing TBL individual readiness assurance test (RAT) scores and group RAT scores of clinical decision-making before and during the pandemic found that the content delivery mode (in-person vs. online) was not significantly different amongst the teams. More research is needed in post-COVID-19 GME [6]. In engineering students, TBL enhanced the correlation of perceived writing skill and the instructors’ assessment [7].

1.2. Combined Team-Based Learning and Problem-Based Learning

Problem-based learning (PBL) facilitates learning and critical thinking by applying problem-solving to relevant issues [8]. In health services, TBL and PBL emphasize collaborative and practical learning to tackle real-world issues in healthcare operations, management, and clinical problem-solving. Developed for medical education in the early 1960s, TBL involves forming small groups of students or professionals who work together to solve complex, multifaceted problems, like those typically encountered in healthcare settings [9].

The focus in PBL is on developing critical thinking [10], communication, and leadership skills, essential for effective health services, as well as required competencies for program accreditation. Participants engage in active learning by researching, discussing, and proposing solutions to these problems, guided by a facilitator rather than a traditional instructor. This approach not only enhances theoretical knowledge but also fosters teamwork, decision-making, and the ability to apply concepts in practical situations, crucial for successful management in the dynamic and challenging field of health services. Variations on traditionally defined TBL and PBL pedagogies have shown promise, and various combined approaches have been recommended [11]. A quantitative path analysis using hierarchical regression of PBL, TBL, and flipped classrooms in graduate and undergraduate business students found improved engagement and significant differences in learning with PBL and TBL. The flipped classroom was non-significant with negative effects. Similar quantitative studies of modified PBL and TBL are needed in health services education [12].

When PBL was applied to health services field studies via community service learning (CSL), the summative assessment of content knowledge improved by 19% relative to lectures (p < 0.0001, two-tailed) and the student perception of the value of both the course and the experience also improved significantly [13]. In a mixed-methods study, PBL and TBL combined with community-based research improved students’ learning; however, students had difficulty working in teams and scheduling with community partners [14]. Interprofessional education (IPE) engages students from several health services disciplines to address a complex, real-world problem. A systematic review identified stakeholder perspectives (learner, teacher, researcher) and willingness to participate as factors for success using this learning approach [15]. However, to our knowledge, constructs associated with the success of combined TBL and PBL in health services have not been studied.

1.3. The Global Pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, teacher stressors soared globally, including technical barriers, as well as the time required to manage an online classroom [16]. However, the implementation of innovative teaching practices during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in improved student evaluations, compared to non-innovative methods [17]. Adaptations to PBL and TBL in the online milieu have been proposed in various student populations [18].

Health services education also faced challenges. Traditionally, health services education functions under a clinical model, i.e., learning and working on site. The swift move to online instruction presented both predictable and unique challenges. The implementation of online instruction was predictably hampered by an educational workforce with limited experience in online methodology. Problem-based learning (PBL) in health services was adapted using familiar case-study methods. However, a sudden shift to virtual platforms required a rethinking of how student and professional teams collaborate and engage remotely in problem-solving. Despite the physical distance, problem analysis continued to play a crucial role, with teams tackling unprecedented real-world healthcare management issues brought on by the pandemic, such as resource allocation, emergency response, and public health strategies. The virtual environment posed challenges in maintaining effective communication and team dynamics. It also tested the co-adaptability and digital literacy of participants and facilitators. On the positive side, this shift expanded the scope of learning by incorporating global perspectives and enabling cross-border collaborations, as professionals worldwide grappled with similar healthcare challenges. The pandemic thus underscored the importance of flexibility, resilience, and innovation in team-based and PBL approaches in health services education.

To understand how learning in health services was impacted during the pandemic, this systematic review was conducted to identify constructs associated with the success of TBL and PBL in health services education.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was guided using the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) process. The PRISMA process is a set of guidelines aimed at improving the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. It helps authors to provide a clear and transparent account of their review process, improving the quality and replicability of systematic reviews. PRISMA focuses on ways in which authors can ensure the clarity and transparency of their report, covering areas such as the title, abstract, methods, results, discussion, and funding.

Key, abbreviated steps in the PRISMA systematic review method are as follows:

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases, registries).

- Present the full search strategy for at least one database.

- State the process for selecting studies.

- Describe the method of data extraction and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators.

- List and define all variables for which data were sought.

- Describe methods used to evaluate the risk of bias.

- Describe the methods of handling data and combining results of studies.

- Give numbers of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions.

- For each study, present characteristics and collected data.

- Summarize the main findings.

- Discuss limitations at study and outcome level, and at the review level.

- Provide a general interpretation of the results and their implications for future research.

The articles identified for the review related to project or team-based learning for health services and used the Xavier University Library’s EBSCOhost website, Advanced Search level. Peer-reviewed publications specific to project- or team-based learning and directly related to health services, but not clinical medicine or medical education, are limited.

2.1. Inclusion Process

The researchers focused on project- or team-based learning articles that were recently published to investigate potential underlying themes related to andragogy methods and/or practices implemented during the pandemic. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) is the National Library of Medicine controlled vocabulary thesaurus utilized to index research articles for PubMed (MEDLINE) and was used to identify key words in the search. This website tool assisted in the research team’s generation of the review’s database search string and related key words to be included in the search. Boolean search operators were used to ensure proper words/phrases to capture all applicable literature for the sample as indicated by MeSH and other identified review terms. The database search conducted on 27 June 2023 using the finalized search string below:

[(problem based learning) OR (problem-based learning) OR (team-based learning) OR (team based learning) OR (project based learning or project-based learning) OR (pbl) AND (healthcare) OR (health care) OR (health services) AND (education) OR (learning) OR (teaching) OR (classroom) NOT (medical) NOT (international) NOT (community service learning)].

To be included in the review, publications had to be published between 1 January 2021 and 31 May 2023. This specific publication date range was utilized by the research team to identify health services andragogy and pedagogy methods related to the review topic, specifically related to and during the COVID-19 global pandemic, and beyond. Articles included in the review had to be classified by the EBSCOhost search database as scholarly (peer-reviewed) articles, published in the English language, and meet the publication date search parameter. To further identify publications specific to the review team’s initiative, additional search parameters included: limiters of academic journals only, coded as United States geography only, not internationally classified, and not conference papers or other citations not qualifying as journal articles/publications.

This study’s information came from secondary data sources (library research database). All of the literature included in this research is publicly available and any individual research subjects (if present) are unidentifiable. As a result, this systematic review qualifies under the “exempt” status in 45 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 46. An institutional review board review was not required, and no consent was necessary.

2.2. Exclusion Process

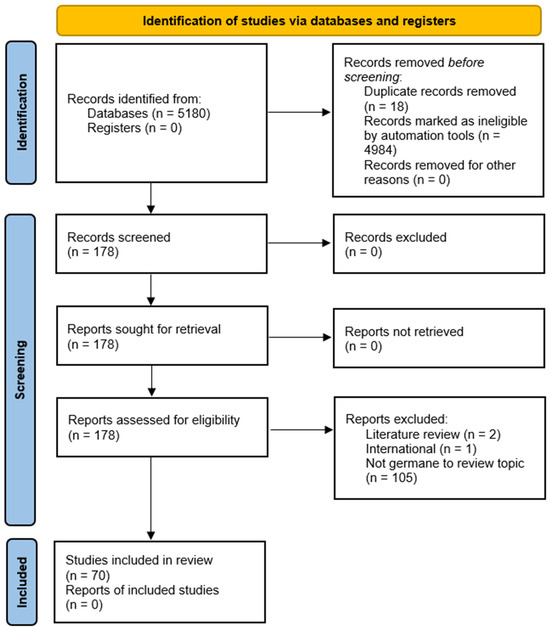

Figure 1 demonstrates the article exclusion process, beginning with the review team’s initial research database search efforts and ending with a final literature sample (n = 70). Initially, 5180 articles focused on problem-based and team-based learning in health services (not medical) and not being international were identified by the research team. The EBSCOhost website assisted in the auto-detection and removal of 4984 ineligible articles and an additional 18 duplicate articles, leaving 178 manuscripts remaining for review.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) figure that demonstrates the study selection process.

The research team consisted of six members, working primarily on a remote/online basis. The 178 manuscripts were each reviewed by at least two team members for the first round of exclusions based upon manuscript title and abstract analysis to ensure that only articles germane to the study’s initiatives were included. Table 1 shows the delineation of article/abstract review assignments, per PRISMA guidelines.

Table 1.

Reviewer assignment of the initial database search findings (full article review).

In addition to removing 5002 articles for not meeting the study criteria, the full text review of the remaining articles resulted in an additional 108 articles being excluded from the review. These additional articles were removed for the following reasons:

- Review articles (2 articles);

- International article (1 article);

- Not germane to the topic (105 articles):

- ○

- International study (10 articles);

- ○

- Not higher education (primary/secondary education only, 3 articles);

- ○

- Specifically medical-related only (48 articles);

- ○

- No problem-based or team-based learning (18 articles);

- ○

- Other non-health services related studies (26 articles).

The research team’s review focused on studies involving team- and problem-based learning activities and related projects in health profession programs at higher education institutions during the pandemic. This was part of their effort to identify potential constructs from the literature for future grant proposals. The team conducted a thorough examination of 70 articles, selected through a database search and an exclusion process as depicted in Figure 1. They used MS Teams to assign internal numbers to each article and then proceeded with in-depth reviews of the full texts. At least two researchers evaluated each article.

The research team held multiple collaborative meetings, both online via webinars and in-person, to discuss coding and identify constructs within the assigned articles. An initial data collection/synthesis spreadsheet was used for article analysis and review team collaboration. For each theme, an occurrence was defined as the included articles in which the theme was identified. More than one theme could occur in any given article. For each theme, the percent instances of attribute was defined as the number of occurrences divided by the total reports of included studies (n = 70) and multiplied by 100.

3. Results

Appendix A [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88] provides the final review’s included articles’ (n = 70) information, to include the review team’s perceived team-based and/or problem-based learning attributes identified in the review process. An analysis of Appendix A revealed eight constructs specific to PBL and TBL in health services education:

- High-impact learning methods for critical thinking;

- Modified problem-based learning, lessons learned/COVID-19 issues;

- Newer methods—simulation, games, puzzle/escape;

- Active learning methods in an online environment (time, effort, scalability);

- Meeting needs of age, cognitive styles, or developmental phase of students;

- PBL/TBL and improvement of instructor feedback or students’ ability to self-assess;

- Cultural competencies and communication;

- Organizational leadership, team-based learning/collaboration.

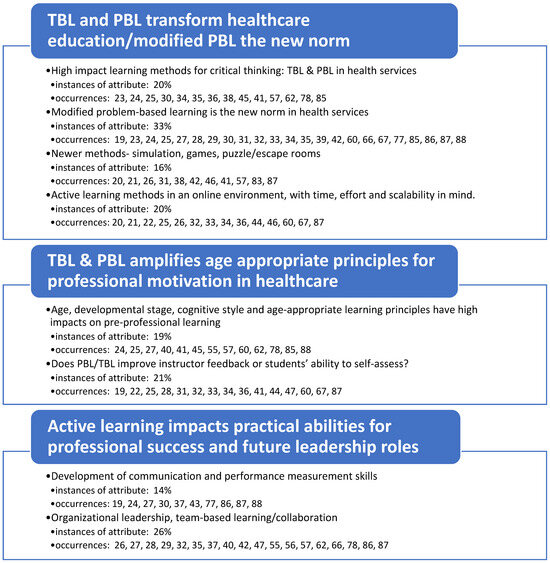

From these eight constructs, three overarching themes emerged and are shown in Figure 2. Figure 2 provides a high-level lens of the three themes and eight constructs identified in the systematic literature review and the frequency of occurrence. These are as follows:

Figure 2.

Occurrences of underlying themes and constructs identified in the literature surrounding team and problem-based learning in health services.

- TBL and PBL transform healthcare education; modified PBL is the new norm.

- TBL and PBL amplify age-appropriate principles for professional motivation in healthcare.

- Active learning impacts students’ practical abilities for professional success and future leadership roles.

Theme 1 highlights the transformational importance of problem-based and team-based learning to healthcare education. Further, modified problem-based learning has emerged as the new norm in health services. Four constructs were clustered under Theme 1. High-impact learning methods for critical thinking had 14 occurrences across the included studies. As described in the Methods and required by the PRISMA guidelines for systematic literature reviews, the number of occurrences was divided by the total reports of included studies (n = 70), and the instances of this construct attribute was calculated at 20%. Modified problem-based learning and lessons learned from COVID-19 issues had 23 occurrences and 33% of the instances. Importantly, this was the highest percentage of instances of any construct. Newer methods, e.g., simulations, games, and puzzles with virtual escape rooms had 11 occurrences and 16% of the instances. Active learning methods in an online environment (time, effort, scalability) had 14 occurrences and 20% of the instances.

Theme 2 identified PBL and TBL as critical amplifiers of age-appropriate principles for professional motivation. Two constructs were clustered under Theme 2. Using TBL and PBL to meet the needs of students by age, cognitive styles, or developmental phase had 13 occurrences and 19% of the instances. The TBL and PBL improvement of instructor feedback or students’ ability to self-assess had 15 occurrences and 21% of the instances.

Theme 3 identified specific ways in which active learning impacts students’ practical abilities for professional success and future leadership roles. Two constructs were clustered under Theme 3. When TBL and PBL were applied, cultural competencies, communication, and performance measurement skills had 10 occurrences and 14% of the instances. Of note, TBL and PBL improved organizational leadership skills, teamwork, and collaboration with 18 occurrences and the penultimate percentage of instances at 26%.

More than one theme could occur in any given article, resulting in a broad range of reasons to incorporate TBL and modified PBL to improve learning in health services education. As we seek new means of preparing future healthcare professionals, these themes and constructs should be considered when designing curricula and professional development experiences.

4. Discussion

The research team successfully identified specific constructs associated with team- and problem-based learning initiatives in health services. These constructs, grouped by the identified themes, encompass various attributes of learning initiatives conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, the identified constructs are interrelated rather than isolated phenomena within TBL and PBL initiatives. This interconnectedness signifies that occurrences in one area often influence or overlap with others, highlighting the complexity and dynamic nature of the identified learning initiatives.

4.1. High-Impact Learning Methods for Critical Thinking

Evidence-based decision support relies on critical thinking skills. Compared to traditional teaching methods, e.g., lectures, PBL and TBL have been shown to support knowledge acquisition, skill development, and critical thinking [23,30]. Definitions of critical thinking [30] overlap with the higher-order Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive development, i.e., apply, analyze, evaluate, create [89]. There are many excellent published descriptions of proposed projects with critical thinking skills for clinical health-related disciplines [78]. However, very little original research has been published in health services to support the effectiveness of PBL and TBL to improve critical thinking under real-world educational conditions [25,47].

Further, student satisfaction with high-impact methods varies [23,24,30]. It is unclear if students at the graduate and undergraduate levels will value improved professional skill acquisition from higher-effort PBL and TBL, compared to traditional teaching methods, such as lectures [23]. More research to study the knowledge, skills, and abilities associated with critical thinking and professional skills is needed, as well as student acceptance.

Although simple in concept, the increased classroom space and materials needed to support students’ team-based projects present additional barriers [23,24]. In addition, smaller class sizes are required for success as the instructor moves into a facilitator role [23]. More research is needed to assess university resource allotment to high-impact courses.

4.2. Modified Problem-Based Learning, Lessons Learned/COVID-19 Issues

In the 1960s, PBL was developed in response to the poor performance of professional skills by medical students [9]. Since that time, many adaptations have been introduced. Reviewers found very few current studies utilizing traditionally defined PBL [24,30]. In addition, few studies addressed learning outcomes in undergraduate student populations [19,30], who may have limited readiness for the internal motivation to learn that is typical of adult learners. More studies are needed in undergraduate health services students.

During COVID-19, modified problem-based learning (mPBL) became the new norm, often in virtual formats [23,27,28]. The team identified both program-specific and interprofessional education methods, during and continuing after the COVID-19 global pandemic [32,34,67,77]. We suggest defining mPBL as PBL with elements of related active learning pedagogies. Most experimental curricula, courses, and studies utilize mPBL, such as project-based workshops [19], IPE [87], or a modification specific to the problem or course [27]. When PBL was paired with CSL in a graduate counseling student population, knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy assessment were all improved at statistically significant levels [25]. In addition, virtual mPBL modules may be used to address specific identified learning needs and gaps [28].

In health services, mPBL tailors the traditional problem-based learning method to better suit the specific needs and context of health services education. It involves presenting students and/or healthcare professionals with realistic scenarios, encouraging them to analyze and solve complex problems related to service delivery. This adaptation incorporates additional structure, guidance, and the integration of foundational knowledge, enhancing the effectiveness and relevance of problem-based learning within the health services domain. Modified PBL has replaced traditionally defined PBL in health services education.

Regardless of the improved content knowledge and professional skill development, however, students may prefer traditional lectures [23]. Traditional teaching is, out of necessity, less confusing, and requires relatively less effort to discern subtle differences in content knowledge and application to less-structured, real-world scenarios. A meta-analysis of combined PBL and TBL versus traditional teaching demonstrated a statistically significant improvement of knowledge and skills; however, student satisfaction was higher with traditional teaching [23].

TBL is an inherently “flipped” pedagogy. Traditionally defined TBL includes the use of individual and team readiness assessment tests, with immediate feedback, to test and document student accountability for work, and it has consistent team members throughout each project [65]. The four steps of traditional TBL are individual student preparation, individual readiness assurance testing (iRAT) and team readiness assurance testing (tRAT), application, and peer assessment [28]. A study of mTBL comparing graded and ungraded iRAT found no difference in scores [29]. The research team identified a subset of articles within this construct that utilize team-based learning with a focus on clinical processes [19,24,32,35,42]. When TBL was paired with Kearsley and Shneiderman’s engagement components in graduate pharmacy students, team support and trust improved their ability to relate [35]. Modified TBL was combined with a technologically enhanced experience in a “flipped” virtual model to engage graduate nurse practitioner students learning teamwork and statistics [65]. Like mPBL, modified TBL (mTBL) has become the new norm. One best practice for this remote or online learning method was keeping consistent teams throughout the entire learning experience, versus switching team members during the initiative [65].

4.3. Newer Methods—Simulation, Games, Puzzle/Escape Rooms

The importance of active learning strategies to engage students in higher education and prepare students to collaborate effectively has been well documented broadly [90]. Since the 1960s, problem-based learning (PBL) and team-based learning (TBL) have been essential instructional approaches in medical school education to prepare students to effectively collaborate in the complex and evolving field of health services [11]. However, the COVID-19 pandemic was a catalyst for additional pedagogical adaptations and highlighted the need for innovative teaching methods that increase student engagement virtually as well as in person. While active learning strategies are commonly used with TBL and PBL among students training in clinical processes, few studies assess their impact in health services education. This lack of transdisciplinary knowledge may be a contributing factor to the confusion of roles within interprofessional learning experiences.

Articles that utilized simulation showed that they were beneficial for students by improving understanding and the clarification of roles. For example, a simulation video resulted in students shifting their focus to a cognitive leadership role through virtual discussions [20]. While in Article 93, the in-person simulation resulted in an appreciation for interprofessional team members and their roles within other health services disciplines, Article 21 utilized a simulation game in the context of an escape room online, in-person, and in hybrid settings utilizing teams and individuals. For each escape room scenario, a case was presented as a prompt that needed to be solved within an allotted time. This resulted in enjoyment and a high level of engagement that ranged from individual proficiency to group communication and collaboration.

Articles that utilized non-lecture-based teaching methods showed that most students favor a deep-learning approach that can be achieved with a flipped classroom [31], concept mapping [41], skill-based activities [42,77,87], or learning laboratories [26,57]. For example, in Articles 42, 47, and 77, students were able to self-direct their learning and improve performance skills by recognizing connections between unfamiliar concepts while practicing professional interactions. Article 57 uniquely implemented new design thinking methods inclusive of five phases: problem analysis, design, development, integration, and evaluation that resulted in deeper problem analysis.

Barriers to these innovative teaching methods to improve student engagement included students reporting awkward interactions with simulations, too many people grouped together, and the cost of time and/or money for planning and implementation. However, overall, these studies show that effective innovative teaching methods use immersive and experiential opportunities that require reflection, discussion, reasoning, and decision-making. The positive effects on student engagement occurred both virtually and in person. Therefore, these findings are generalizable to the diverse higher education formats of multiple health services professions. This may result in a higher level of critical thinking and improved interprofessional collaboration within health services.

4.4. Active Learning Methods in an Online Environment (Time, Effort, Scalability)

Modalities for active learning include PBL and TBL. TBL exercises, such as debates, group work, and peer review prepare students to give and receive respect in a multidisciplinary, hierarchical environment. Analyses of best-practice reports and case studies, i.e., case series, single case reports, and practice scenarios, are examples of PBL. Students’ abilities to communicate, verbally and non-verbally, and function in the delivery of health services has become an increasingly difficult transition post-COVID-19. By incorporating active PBL and practicing effective team processes and communication in an online milieu, students may be better prepared for their transition to multidisciplinary professional practice.

With a greater emphasis on active learning in the classroom, it is necessary to consider the adaptations needed to provide opportunities in an online environment, which is especially true post-COVID-19. Learning virtually serves as complementary to traditional education, but it also supports non-traditional students and students taking courses or training for continuing education or skill enhancement, and it reduces barriers between professionals working collaboratively. Active learning allows for introspection and reflection while professionals and students share experiences, assimilate into roles that enhance safety, and learn to routinely incorporate evidence-based practice before entering the workforce [20]. Students report feeling more engaged and having higher satisfaction when active learning is included in their education [33]. Further, students are more equipped to both educate others and delegate work, mimicking real-world workplaces that require working on teams and solving analytical problems with others [20,21].

Much has changed in higher education and there is greater understanding of the unique needs of learners when working virtually, including generational contexts and preferences [34]. Virtual active learning requires greater student responsibility [34] and an emphasis on the synthesis of complex information and critical thinking [34]. Virtual active learning gives students a chance to demonstrate and apply knowledge gained in coursework and prior experience [36]. There is a great opportunity to connect policy, procedure and guideline awareness [36] with evidence-based practice and safety across roles [19].

Online active learning often uses case-study review, but it also includes procedural reviews, escape rooms (for problem solving and use of constructivism), and self and group reflection [20,21,33,34,36,54]. Using a multi-modal discussion to brainstorm ahead of active learning and debrief after can help the online environment to feel more effective and connected, and it can be key to engagement [20]. Virtual active learning is impactful, with 360’ immersion using photo and video to understand settings and patient needs even when being in person is not feasible due to distance (national and international perspectives) or due to illness or related health concerns, e.g., COVID-19 [33].

The literature suggests that some components of working in an online environment can be cost effective, depending on the level of engagement between the faculty and the student [20,21,33]. A reduction in effort with each iteration of a project may occur if there are not significant changes as well as an inverse relationship with the ability to scale to larger groups over time [20,21,33]. The setup and organization of a project can positively or negatively impact engagement but requires proper planning upfront and purposeful goal setting to reduce costs and the need for a large number of staff to manage the project [21]. And, if the time is spent upfront, subsequent offerings of the same project have been noted to be at a reduced expense—both in time and resources [20]. Students benefit from having some freedom of choice [54] and having multiple methods for learning and interaction, which requires more staff and will not reduce the cost but instead provide flexible learning environments [20]. Recommendations include having options that work on a PC or laptop vs. on an iPhone [20,54], and having opportunities for pre-work that is asynchronous and offered in video or online discussion formats, giving the feel of individualization while still being standardized [20,33,34,54]. User control features allow for concise, “bite-size” learning and create more frequent, consistent, and immediate opportunities for feedback [34].

Although higher education administrators commonly allow a higher capacity in courses that are offered virtually vs. in-person, this is not a well-supported decision. There is a notable increased time, effort, and difficult scalability of online courses, in general, and when active learning is included, there are additional barriers to appropriate project management in resource-limited universities. To provide timely feedback prior to graded exams, faculty challenges included ongoing quality improvement efforts, increased time for grading active learning assignments, and additional faculty members to coordinate and engage when the faculty: student ratio exceeded 1:27 [54]. In an online environment, PBL increased facilitators’ time administering the active learning group work, as technical assistance for students was needed and facilitators were not able to do both simultaneously. Creating PBL in a virtual environment also required additional faculty training time [67]. PBL active learning via real-time teleconferencing was used to meet the interprofessional teamwork core competency. The faculty created case studies, guided questions, coordinated invited healthcare professionals to round out the multidisciplinary team, and created alternatives to a traditional exam. A “360 Workshop” with complex virtual interactive puzzles, documents, and content covered in the course and outside partners dramatically increases faculty time and effort [33].

In summary, in an online environment, active learning methods (PBL or TBL) affect time, effort, and scalability and require a reduced number of students per course instructor, compared to traditional teaching.

4.5. Meeting Needs of Age, Cognitive Styles, or Developmental Phase of Students

Age, developmental stage, cognitive style, and age-appropriate learning principles have high impacts on learning. Adult learners’ engagement and achievement are improved by planned learning experiences targeted to their developmental stage and pragmatic needs. Andragogy, i.e., adult learning principles, gained attention in the 1970s, include self-direction, relevant material, problem-based learning, self-motivation, and application of life experiences [91]. Over time, the principles of adult learning have been expanded and applied by researchers, educators, trainers, and for-profit universities, e.g., interaction, small learning teams, and clear and timely feedback [92]. Yet, pedagogic principles for the traditional education of children prevail in higher education. Adult learning principles, as opposed to pedagogy, are rarely planned with intention. The implementation of TBL and PBL meets the needs of adult learners. Although programs and courses may utilize adult learning principles, few studies assess the impact in health services disciplines [11].

Andrienko et al. (2021) showed that team-based learning (TBL) has a positive effect on outcomes related to adult learning in undergraduate higher education, such as business communication, global employment, and intercultural competence [56]. Two-team simulations are efficient and effective [62]. One benefit of the two-team training approach is the motivation generated by the active observer role during simulation exercises. Further, motivation and self-direction were improved when the TBL case study was used in groups of graduate students at different levels [55]. White et al. modified traditional elements of TBL to create an online graduate statistics course, e.g., immediate student-to-student feedback and timely faculty feedback to support students in areas of difficulty. Computer-based testing is preferred by 79% of first-year doctoral students, due to its convenience and immediate feedback [60]. TBL as a tool is particularly useful for teaching complex subject matter to adult learners [66]. TBL enhances self-awareness of learning needs and thinking about thinking (metacognition) in graduate students [41]. When master’s-level students engaged in the application of material in a real-world context, they were able to clearly connect didactic material to their discipline. PBL increased knowledge, attitudes, and self-assessment at large effect sizes, with statistically significant results [25]. A mock board presentation was used to simulate the real-world experience for graduate nursing students [78].

However, barriers to the implementation of PBL include faculty resistance due to inadequate facilitation skills, frustrated student learners unfamiliar with the process, and the complexity of cases being mismatched to with knowledge level and resources [24]. In addition, students expressed difficulty managing their own small groups [55]. Further, the “flipped” classroom approach did not support student motivation in undergraduate nursing students [45].

Collectively, these studies show that team-based learning (TBL) and PBL have a positive effect on outcomes related to adult learning in higher education. The findings can be applied to both undergraduate and graduate programs. Higher education in health-related fields, which require knowledge, skills, and the ability to apply business, clinical, change management, communication, and other strategies to everyday practice, would improve outcomes by implementing hybrid TBL and PBL projects based on the principles of adult learning.

4.6. PBL/TBL and Improvement of Instructor Feedback or Students’ Ability to Self-Assess

Instructor feedback to students is expected and impacts student satisfaction. Formative assessments provide quick and informative feedback, while summative assessments evaluate knowledge and comprehension. Group work and peer-to-peer learning are examples of TBL and active learning. Case studies are used for PBL. The faculty provided timely feedback for active learning assignments prior to graded exams [54]. “Flipped” classroom interaction with instructor provides immediate feedback, and a TBL “escape room” provides immediate feedback and is viewed positively by participants [36]. To provide immediate feedback, the faculty created case studies, guided questions, invited healthcare professionals to round out the multidisciplinary team, and created an alternative to a traditional exam, via a “360 Workshop” with complex virtual interactive puzzles, documents, and content covered in the course [87].

Students’ abilities to self-assess, and the results, are highly variable. Critical thinking skills contribute to accurate self-assessment [41]. Mid-level performing students (mean 84%) most accurately predicted their final score (p < 0.02) [41]. Although the results were not statistically significant, lower-performing students (<80% quiz score) overestimated their expected grade, whereas high-performing students underestimated their success [41]. When validated instruments for attitudes toward research and research self-efficacy scales were applied to study self-assessment, the results showed a statistically significant improvement in self-efficacy with a large mean increase of 18.4 (CI95 10.6–26.2). Students perceived themselves to be competent researchers, and their self-assessment was validated by the large effect size and statistically significantly improved scores in discipline knowledge and attitude toward research [25]. In addition to positive effects on critical thinking, reflective writing improved self-assessment [93]. Although TBL via group concept mapping significantly increased quiz scores (p < 0.001), it did not improve self-assessment (p = 0.1) on a summative assessment [41], nor was self-rated knowledge statistically significant after the TBL intervention (p = 0.64) [22].

4.7. Cultural Competencies and Communication

Value-based care requires health services professionals to collaborate and communicate in the continuous improvement of health outcomes [86]. Team- and problem-based learning is an effective tool for health services students to develop the communication and performance measurement skills needed to assess these improvements. The development of these skills was evidenced by an increase in confidence to perform technical skills and improved cultural competency to work in cross-cultural situations [43,86,94]. The importance of communication as a skill has been documented since the 1970s and current curricula often meet these expectations by incorporating PBL experiences [86,95]. PBL learning experiences build on prior knowledge and allow students to communicate their understanding of concepts with real-world practice [87]. The PBL approach blends theory and practice, and when used repeatedly with progressively increased complexity, foundational knowledge and communication skills improve [88]. As a result, health services students exposed to PBL have an advantage with problem solving, incorporating basic concepts into professional application, and excelling during fellowships [87], and this starts in the classroom.

For example, in Article 19 using project-based learning, health services students were able to develop communication skills to address public health concerns regarding sexual health education within a specific population of older adults in a workshop setting. This workshop helped to expose biased views that would impact students’ professional ability to disseminate and communicate information related to the topic of sex and aging as staff in long-term care settings. Additionally, it contributed to addressing the lack of professional skills when entering the workforce with necessary foundational gerontological knowledge [19]. As a result, students not only increased their awareness of late-life sexual health and behavior but demonstrated confidence and utilized creative strategies to discuss a sensitive topic. Moreover, students stated that they “appreciated the opportunity to develop transferable pre-professional skills” [19].

4.8. Organizational Leadership, Team-Based Learning/Collaboration

Team-based learning is a potent tool for organizations aiming to align their strategies and directives with collaborative and dynamic engagement. By fostering a culture of teamwork and collaboration, organizations can effectively implement strategies that capitalize on collective intelligence and varied perspectives. Teams provide a platform for integrating diverse skill sets, knowledge bases, and experiences, enhancing problem-solving and decision-making processes. Additionally, team-based learning cultivates a sense of ownership and shared responsibility among team members, aligning them with the organization’s strategic goals. This approach encourages innovative thinking and promotes adaptability, critical components in responding to evolving market trends and disruptions. By employing team-based learning as a fundamental strategy, organizations can bolster their ability to navigate complexity, drive innovation, and achieve sustainable success in the fast-paced business landscape.

Articles that supported a construct surrounding the use of team-based learning in health services also furthered organizational leadership and/or an organizational strategy. Often conducted or tested in higher-education environments, such learning activities worked to further healthcare organizational outcomes or other performance indicators [22,26,27,37]. Additionally, several team-based learning initiatives also infused interprofessional learning and collaboration [37,40]. Often driven by difficult clinical situations, patient diagnoses, or other environmental factors, the use of team-based learning has demonstrated the ability to improve organizational metrics and support the organizational leadership’s initiatives [42,47].

The research team identified several articles that not only focus on the training and implementation of team-based learning in a real-world environment to achieve better patient and/or organizational outcomes, but also aim to grow and support a safety culture [27,56,57]. Implementing team-based learning in the health services workplace can significantly enhance safety standards and practices. In a healthcare setting, collaboration and effective communication among team members are paramount to ensuring patient safety and optimal outcomes. Team-based learning facilitates interdisciplinary training and knowledge sharing, ensuring that healthcare professionals understand each other’s roles, responsibilities, and expertise [57,78]. Through simulated scenarios and real-world case discussions, teams develop a deeper understanding of protocols, emergency procedures, and best practices for patient care [41]. This approach also cultivates a culture of accountability and shared responsibility for patient safety, encouraging individuals to speak up and voice concerns, ultimately minimizing errors and fostering a safer environment for both patients and health services professionals [26,27,43,86].

4.9. Limitations

Systematic reviews typically strive to eliminate bias, but we would be remiss not to include the limitations of our study. Although we attempted to reduce bias in our study by justifying our choice to use PRISMA guidelines, it can never be fully eliminated. With small sample sizes, several of the studies included in the review could overestimate the intervention effects. Further, publication bias is also more likely to occur in small studies (due to not being statistically significant), of which we reviewed many [19,20,24,25,26,28,34,42,45,51,52]. Another limitation may include bias in our conclusions. As we attempted to categorize 70 studies into three underlying themes, our conclusions may have been broad [36,43,48,49,50,52,53,54,59,61,69,82].

5. Conclusions

To understand how learning in health services was impacted during the pandemic, this systematic review uniquely found eight constructs associated with the combined success of problem-based learning (PBL) and team-based learning (TBL) in health services education. PBL and TBL are integral to the preparation of students in health services and mimic the roles and responsibilities that exist as they enter their respective occupations. Notably, active learning impacts practical abilities for professional success and future leadership roles. However, modified PBL and TBL are the new norm in health services education because they amplify age-appropriate principles for professional motivation in healthcare. Importantly, the principles of adult learning are met by mPBL and mTBL, including choice, flexibility, and the unique learning needs of each individual.

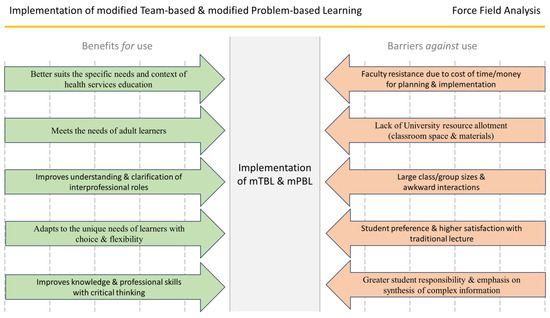

While the benefits of implementing mTBL and mPBL contribute to the critical thinking, motivation, and practical abilities necessary for success in healthcare, it comes with challenges that need to be considered. A key takeaway is the necessity to creatively work through implementation barriers. To assist with the implications of results and summarize this review’s efforts and initiatives for future research, the research team completed a force field analysis of perceived positive and negative influences on the use of mTBL and mPBL in higher education. The force field analysis (Figure 3) compares the benefits and barriers of implementing modified team-based learning (mTBL) and modified problem-based learning (mPBL) in health services education.

Figure 3.

Force-field analysis of influential factors surrounding modified team-based and problem-based learning in health services.

Based on our results, there are significant forces making implementation difficult. Important barriers include the lack of university resources and space allocation, a counter-productively large class size, lower student satisfaction scores, and limited faculty engagement, or the lack thereof. When implementation barriers are not recognized or mitigated, the ramifications are experienced by the students and amongst the faculty. Burnout amongst faculty may occur along with lower student satisfaction scores affecting faculty attainment of desirable annual evaluation scores, promotion, and tenure.

Considering these barriers, a practical suggestion for an educational intervention with mTBL and mPBL is the use of quick real-time assessments with the delivery of course content. Several ways this can be easily accomplished include using various student engagement platforms such as Socrative, EdPuzzle, Kialo Edu, and Padlet. These student engagement platforms differ from gamification apps because their assessments are not based on competitive performance against other students. Engagement platforms provide students an individualized opportunity to actively participate with course content while enabling instructors to collectively gauge their understanding with real-time assessment and data collection. These and other engagement platforms can assist students with the increased responsibility for synthesis of complex information by simplifying the delivery of course content. They can be used within traditional lectures or with large class and group sizes and remove awkward interactions. Many engagement platforms offer a free basic account to educators with autogenerated content and online storage of data results to reduce or mitigate the barriers of administrative time, money, and the lack of university resources. As a result, the use of engagement platforms could streamline the benefits of implementing mPBL and mTBL and address many implementation barriers.

As faculty members continue to strive to better understand the unique developmental needs of undergraduate student populations, future studies are needed to identify effective mPBL and mTBL strategies in health services education to help them to progress as internally motivated learners. Most studies in this systematic review were based on qualitative data and student perception. Specifically, experimental studies are needed to collect quantitative data to test the association of knowledge, skills, and abilities needed for professional practice compared to students’ perceived level of knowledge, skills, and abilities. Time and effort studies are needed to determine the time, effort, faculty, support staff, and resource allocation needed to implement and scale up effective active and experiential learning methods, including mPBL and mTBL, while avoiding burnout. In doing so, given the positive and negative aspects of remote study and work during the COVID-19 pandemic, the implementation of effective mPBL and mTBL strategies can help prospective students to adjust to higher-education expectations and prepare them to function in a complex, multidisciplinary workplace.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to this review in accordance with ICMJE standards. E.S.A. and C.L. primarily led the research, team initiatives and provided guidance throughout the research process. E.S.A., C.L., A.A.W., K.A. and A.V. contributed to investigation into the research topic, participation in the method of the review, and original drafting of the manuscript. Discussion and analyses of review and topic modeling results were conducted by all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The research team thanks Marki Anderson, MHSA, for her efforts in initial article review efforts and early manuscript editing initiatives.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Summary of findings (n = 70).

| Article Number and Author(s) | Article Title and Publication | Population | Intervention/Study Design | Team-Based and/or Problem-Based Learning Attributes |

| [19] Naar, J. et al. | Experiential education through project-based learning: Sex and aging Gerontology and Geriatrics Education |

|

|

|

| [20] Littleton, C. et al. | What Would You Do? Engaging Remote Learners Through Stop-Action Videos Nurse Educator |

|

|

|

| [21] Helbing, R. et al. | In-person and online escape rooms for individual and team- basedlearning in health professions library instruction Journal of the Medical Library Association |

|

|

|

| [22] Whillier, S. et al. | Team-based learning in neuroanatomy Journal of Chiropractic Education |

|

|

|

| [23] Luke, A. et al. | Effectiveness of Problem-Based Learning versus Traditional Teaching Methods in Improving Acquisition of Radiographic Interpretation Skills among Dental Students—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

|

| |

| [24] Henderson, K. et al. | Addressing Barriers to Implementing Problem-Based Learning AANA Journal |

|

|

|

| [25] Hurt-Avila, K. et al. | Teaching Counseling Research and Program Evaluation through Problem-Based Service Learning Journal of Creativity in Mental Health |

|

|

|

| [26] Shorten, A. et al. | Development and implementation of a virtual collaborator to foster interprofessional team-based learning using a novel faculty-student partnership Journal of Professional Nursing |

|

|

|

| [27] Manske, J. et al. | The New to Public Health Residency Program Supports Transition to Public Health Practice |

|

| |

| [28] Veneri, D. et al. | Flop to Flip: Integrating Technology and Team-Based Learning to Improve Student Engagement Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice |

|

|

|

| [29] Eudaley, S. et al. | Student Performance on Graded Versus Ungraded Readiness Assurance Tests in a Team-Based Learning Elective American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education |

|

|

|

| [30] Seibert, S. | Problem-based learning: A strategy to foster generation Z’s critical thinking and perseverance Teaching and Learning in Nursing |

|

|

|

| [31] Walker, J. et al. | A deep learning approach to student registered nurse anesthetist (SRNA) education International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship |

|

|

|

| [32] Bavarian, R. et al. | Implementing Virtual Case-Based Learning in Dental Interprofessional Education Pain Medicine |

|

|

|

| [33] Woodworth, J. | Nursing Students’ Home Care Learning Delivered in an Innovative 360-Degree Immersion Experience Nurse Educator |

|

|

|

| [34] Tomesko, J. et al. | Using a virtual flipped classroom model to promote critical thinking in online graduate classes in the United States: a case presentation Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions |

|

|

|

| [35] Carpenter, R. et al. | The Student Engagement Effect of Team-Based Learning on Student Pharmacists American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education |

|

|

|

| [36] Diaz, D. et al. | Using Experiential Learning in Escape Rooms to Deliver Policies and Procedures in Academic and Acute Care Settings Nursing Education Perspectives |

|

|

|

| [37] Hopkins, K. & Afkinich, J. | Diversifying the Pipeline of Social Work Students Prepared to Implement Performance Measurement Journal of Social Work Education |

|

|

|

| [38] Muirhead, L. et al. | Role Reversal: In-Situ Simulation to Enhance the Value of Interprofessional Team-Based Care Journal of Nursing Education |

|

|

|

| [39] Yang, S. et al. | The impact of dental curriculum format on student performance on the national board dental examination Journal of Dental Education |

|

|

|

| [40] Avery, M. et al. | Improved Self-Assessed Collaboration Through Interprofessional Education: Midwifery Students and Obstetrics and Gynecology Residents Learning Together Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health |

|

|

|

| [41] Martirosoy, A. & Moser, L. | Team-based Learning to Promote the Development of Metacognitive Awareness and Monitoring in Pharmacy Students American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education |

|

|

|

| [42] Powers, K. et al. | Interprofessional student hotspotting: preparing future health professionals to deliver team-based care for complex patients Journal of Professional Nursing |

|

|

|

| [43] Elaimy C. et al. | Availability of Didactic and Experiential Learning Opportunities in Veterinary Practice at US Pharmacy Programs American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education |

|

|

|

| [44] Duck, A. et al. | A pedagogical redesign for online pathophysiology Teaching and Learning in Nursing |

|

|

|

| [45] Pence, P. et al. | Flipping to Motivate: Perceptions Among Prelicensure Nursing Students Nurse Educator |

|

|

|

| [46] Lybarger, K. et al. | Annotating social determinants of health using active learning, and characterizing determinants using neural event extraction Journal of Biomedical Informatics |

|

|

|

| [47] Powell, B. et al. | A Concept Mapping Activity to Enhance Pharmacy Students’ Metacognition and Comprehension of Fundamental Disease State Knowledge American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education |

|

|

|

| [48] Flores-Sandoval, C. et al. | Interprofessional team-based geriatric education and training: A review of interventions in Canada Gerontology and Geriatrics Education |

|

|

|

| [49] Blaine, K. et al. | Training Anesthesiology Residents to Care for the Traumatically Injured in the United States Anesthesia and Analgesia |

|

|

|

| [50] Acker, L. et al. | Perioperative Management of Flecainide: A Problem-Based Learning Discussion A&A Practice |

|

|

|

| [51] McCaffery, J. et al. | An Interprofessional Education (IPE) Experience with a Scaffolded Teaching Design Journal of Allied Health |

|

|

|

| [52] Prince, A. et al. | The Clarion Call of the COVID-19 Pandemic: How Medical Education Can Mitigate Racial and Ethnic Disparities Academic Medicine |

|

|

|

| [53] Mattingly, J. | Fostering Cultural Safety in Nursing Education: Experiential Learning on an American Indian Reservation Contemporary Nurse: A Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession |

|

|

|

| [54] Williams, C. et al. | Adapting to the Educational Challenges of a Pandemic: Development of a Novel Virtual Urology Subinternship During the Time of COVID-19 Urology |

|

|

|

| [55] Tomeh, H. et al. | Self-motivation and self-direction in team-based and case-based learning Journal of Dental Education |

|

|

|

| [56] Andrienko, T, et al. | Developing Intercultural Business Competence via Team Learning in Post-Pandemic Era Advanced Education |

|

|

|

| [57] Henriksen, K. et al. | Pursuing Patient Safety at the Intersection of Design, Systems Engineering, and Health Care Delivery Research: An Ongoing Assessment Journal of Patient Safety |

|

|

|

| [58] Meeuwissen, S. et al. | Enhancing Team Learning through Leader Inclusiveness: A One-Year Ethnographic Case Study of an Interdisciplinary Teacher Team Teaching and Learning in Medicine |

|

|

|

| [59] Tarras, S. et al. | Effective Large Group Teaching for General Surgery Surgical Clinics of North America |

|

|

|

| [60] Franic, D. et al. | Doctor of pharmacy student preferences for computer-based vs. paper-and-pencil testing in a social and administrative pharmacy course Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning |

|

|

|

| [61] Mills, M. & Winston, B. | Designing and Implementing Problem Based Learning Techniques to Supplement Clinical Experiences Journal of Allied Health |

|

|

|

| [62] Clapper, T. | Getting Better Together: The Two-Team Training Approach in Simulation-Based Education The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing |

|

|

|

| [63] Brown, J. et al. | Team-Based Coaching Intervention to Improve Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: A Cluster-Randomized Trial Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology |

|

|

|

| [64] Parker, Z. et al. | Changing Geographic Distributions of Coccidioides Spp. in the United States: A Narrative Review of Climate Change Implications International Journal of Infectious Diseases |

|

|

|

| [65] Guzman, V. et al. | A Comparative Case Study Analysis of Cultural Competence Training at 15 U.S. Medical Schools Academic Medicine |

|

|

|

| [66] White, K. et al. | Engaging Online Graduate Students With Statistical Procedures: A Team-Based Learning Approach Nurse Educator |

|

|

|

| [67] Haley, C. | Adapting problem-based learning curricula to a virtual environment Journal of Dental Education |

|

|

|

| [68] Wilson, M. | Interprofessional Education on Pain and Opioid Use Meets Team-based Learning Needs Pain Management Nursing |

|

|

|

| [69] Soncrant, C. et al. | Sharing Lessons Learned to Prevent Adverse Events in Anesthesiology Nationwide Journal of Patient Safety |

|

|

|

| [70] Raff, A. | Great nephrologists begin with great teachers: update on the nephrology curriculum Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension |

|

|

|

| [71] Awan, O. | The Flipped Classroom: How to Do it in Radiology Education Academic Radiology |

|

|

|

| [72] Souza, I. | Teaching syndemic theory in a High School class: a Problem Based Learning approach International Journal of Epidemiology |

|

|

|

| [73] Ha, T. et al. | A new strategy for teaching Epidemiology in Public Health Education: Hybrid Team Based Learning-Personalised Education International Journal of Epidemiology |

|

|

|

| [74] Ackermann, D. et al. | Rapid Evidence for Practice modules: using team-based learning to teach evidence-based medicine International Journal of Epidemiology |

|

|

|

| [75] Snow, T. et al. | Implementation of a Virtual Simulation-based Teamwork Training Program for Emergency Events in the Perioperative Setting Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing |

|

|

|

| [76] Cai, L. et al. | Implementation of flipped classroom combined with case-based learning: A promising and effective teaching modality in undergraduate pathology education Medicine |

|

|

|

| [77] Beebe, H. et al. | A COVID-Related Inquiry-Focused Online Assignment for Undergraduate Nursing Students The Journal of Nursing Education |

|

|

|

| [78] Griswold, C. & Koss, J. | Experiential Learning Through a Board Presentation Assignment Nurse Educator |

|

|

|

| [79] Ajayi, T. et al. | Cross-Center Virtual Education Fellowship Program for Early-Career Researchers in Atrial Fibrillation Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology |

|

|

|

| [80] Wiljer, D. et al. | Exploring Systemic Influences on Data-Informed Learning: Document Review of Policies, Procedures, and Legislation from Canada and the United States Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions |

|

|

|

| [81] Kaul, V. et al. | Delivering a Novel Medical Education Escape Room at a National Scientific Conference: First Live, Then Pivoting to Remote Learning Because of COVID-19 Chest |

|

|

|

| [82] Moran, V. et al. | Changes in attitudes toward diabetes in nursing students at diabetes camp Public Health Nursing |

|

|

|

| [83] Abuqayyas, S. et al. | Bedside Manner 2020: An Inventory of Best Practices Southern Medical Journal |

|

|

|

| [84] Martinchek, M. et al. | Active Learning in the Virtual Environment Journal of Allied Health |

|

|

|

| [85] Hughes, V. et al. | Strengthening internal resources to promote resilience among prelicensure nursing students Journal of Professional Nursing |

|

|

|

| [86] Blazer, D. et al. | The Great Health Paradox: A Call for Increasing Investment in Public Health Academic Medicine |

|

|

|

| [87] Vanderhoof, M. & Miller, S. | Utilizing innovative teaching methods to design a new geriatric pharmacy elective Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning |

|

|

|

| [88] Morrow, E. et al. | Confidence and Training of Speech-Language Pathologists in Cognitive-Communication Disorders: Time to Rethink Graduate Education Models? American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology |

|

|

|

References

- International Labour Office. Global Skills Trends, Training Needs and Life Long Learning Strategies for the Future of Work (International Labour Conference Report); International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, J.V.; Traylor, A.M.; Kilcullen, M.P.; Perez, J.A.; Schweissing, E.J.; Venkatesh, A.; Salas, E. Cross-Disciplinary Care: A Systematic Review on Teamwork Processes in Health Care. Small Group Res. 2020, 51, 125–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelson, L.K.; Sweet, M. The Essential Elements of Team-Based Learning. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-R.; Park, E. Team-Based Learning Experiences of Nursing Students in a Health Assessment Subject: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.-Y.; Liu, C.; Hsieh, P.-L. Effects of Team-Based Learning on Students’ Teamwork, Learning Attitude, and Health Care Competence for Older People in the Community to Achieve SDG-3. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babenko, O.; Ding, M.; Lee, A.S. In-Person or Online? The Effect of Delivery Mode on Team-Based Learning of Clinical Reasoning in a Family Medicine Clerkship. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Zha, S.; Estis, J.; Li, X. Advancing Engineering Students’ Technical Writing Skills by Implementing Team-Based Learning Instructional Modules in an Existing Laboratory Curriculum. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalinus, N.; Nabawi, R.; Mardin, A. The seven steps of project based learning model to enhance productive competences of vocational students. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technology and Vocational Teachers (ICTVT 2017); Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskola, E.L. Information literacy of medical students studying in the problem-based and traditional curriculum. Inf. Res. 2005, 10, 203–238. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1082011.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Walsh, A. The Tutor in Problem-Based Learning: A Novice’s Guide; Program for Faculty Development, McMaster University, Faculty of Health Sciences: Hamilton, ON, USA, 2005; Available online: https://srs-slp.healthsci.mcmaster.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/novice-tutor-guide-2005.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- Dolmans, D.; Michaelsen, L.; van Merriënboer, J.; van der Vleuten, C. Should we choose between problem-based learning and team-based learning? No, combine the best of both worlds! Med. Teach. 2015, 37, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umar, M.; Ko, I. E-Learning: Direct Effect of Student Learning Effectiveness and Engagement through Project-Based Learning, Team Cohesion, and Flipped Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander Eileen, S.; Browne, F.R.; Eberhart, A.E.; Rhiney, S.L.; Janzen, J.; Dale, K.; Vasquez, P. Community Service-Learning Improves Learning Outcomes, Content Knowledge, and Perceived Value of Health Services Education: A Multiyear Comparison to Lecture. Int. J. Res. Serv.-Learn. Community Engag. 2020, 8, 18079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, J.; Santos, R. Combining project-based learning and community-based research in a research methodology course: The lessons learned. Int. J. Instr. 2018, 11, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieneck, C.; Wang, T.; Gibbs, D.; Russian, C.; Ramamonjiarivelo, Z.; Ari, A. Interprofessional Education and Research in the Health Professions: A Systematic Review and Supplementary Topic Modeling. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapproth, F.; Federkeil, L.; Heinschke, F.; Jungmann, T. Teachers’ experiences of stress and their coping strategies during COVID-19 induced distance teaching. J. Pedagog. Res. 2020, 4, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.H.; Huang, L.R.; Lin, S.H. Why teaching innovation matters: Evidence from a pre- versus peri-COVID-19 pandemic comparison of student evaluation data. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 963953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suartama, I.K.; Triwahyuni, E.; Suranata, K. Context-Aware Ubiquitous Learning Based on Case Methods and Team-Based Projects: Design and Validation. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naar, J.J.; Weaver, R.H.; Sonnier-Netto, L.; Few-Demo, A. Experiential education through project-based learning: Sex and aging. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2021, 42, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littleton, C.; Bolus, V.; Wood, T.; Clark, J.; Wingo, N.; Watts, P. What Would You Do?: Engaging Remote Learners through Stop-Action Videos. Nurse Educ. 2023, 48, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helbing, R.R.; Lapka, S.; Richdale, K.; Hatfield, C.L. In-person and online escape rooms for individual and team-based learning in health professions library instruction. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2022, 110, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whillier, S.; Lystad, R.P.; El-Haddad, J. Team-based learning in neuroanatomy. J. Chiropr. Educ. 2021, 35, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, A.M.; Mathew, S.; Kuriadom, S.T.; George, J.M.; Karobari, M.I.; Marya, A.; Pawar, A.M. Effectiveness of Problem-Based Learning versus Traditional Teaching Methods in Improving Acquisition of Radiographic Interpretation Skills among Dental Students—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9630285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, K.J.; Coppens, E.R.; Burns, S. Addressing Barriers to Implementing Problem- Based Learning. AANA J. 2021, 89, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hurt-Avila, K.M.; DeDiego, A.C.; Starr, J. Teaching Counseling Research and Program Evaluation through Problem-Based Service Learning. J. Creat. Ment. Health 2023, 18, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorten, A.; Cruz Walma, D.A.; Bosworth, P.; Shorten, B.; Chang, B.; Moore, M.D.; Vogtle, L.; Watts, P.I. Development and implementation of a virtual “collaboratory” to foster interprofessional team-based learning using a novel faculty-student partnership. J. Prof. Nurs. 2023, 46, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manske, J.; Hayes, H.; Zahner, S. The New to Public Health Residency Program Supports Transition to Public Health Practice. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2022, 28, E728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veneri, D.A.; Mongillo, E.M.N. Flop to Flip: Integrating Technology and Team-Based Learning to Improve Student Engagement. Internet J. Allied Health Sci. Pract. 2021, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eudaley, S.T.; Farland, M.Z.; Melton, T.; Brooks, S.P.; Heidel, R.E.; Franks, A.S. Student Performance on Graded versus Ungraded Readiness Assurance Tests in a Team-Based Learning Elective. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2022, 86, 1038–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seibert, S.A. Problem-based learning: A strategy to foster generation Z’s critical thinking and perseverance. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2021, 16, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J.K.L.; Richard-Eaglin, A.; Hegde, A.; Muckler, V.C. A deep learning approach to student registered nurse anesthetist (SRNA) education. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2021, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavarian, R.; de Dhaem, O.B.; Shaefer, J.R. Implementing Virtual Case-Based Learning in Dental Interprofessional Education. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodworth, J.A. Nursing Students’ Home Care Learning Delivered in an Innovative 360-Degree Immersion Experience. Nurse Educ. 2022, 47, E136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomesko, J.; Cohen, D.; Bridenbaugh, J. Using a virtual flipped classroom model to promote critical thinking in online graduate courses in the United States: A case presentation. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2022, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, R.E.; Silberman, D.; Takemoto, J.K. The Student Engagement Effect of Team-Based Learning on Student Pharmacists. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2022, 86, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, D.A.; McVerry, K.; Spears, S.; Dèaz, R.Z.; Stauffer, L.T. Using Experiential Learning in Escape Rooms to Deliver Policies and Procedures in Academic and Acute Care Settings. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2021, 42, E168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, K.; Meyer, M.; Afkinich, J. Diversifying the pipeline of social work students prepared to implement performance measurement. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2022, 58, 702–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muirhead, L.; Kaplan, B.; Childs, J.; Brevick, I.; Cadet, A.; Ibraheem Muhammad, Y.; Kemp, L.; Coffee-Dunning, K.; Echt, K.V. Role Reversal: In-Situ Simulation to Enhance the Value of Interprofessional Team-Based Care. J. Nurs. Educ. 2022, 61, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Edwards, P.C.; Zahl, D.; John, V.; Bhamidipalli, S.S.; Eckert, G.J.; Stewart, K.T. The impact of dental curriculum format on student performance on the national board dental examination. J. Dent. Educ. 2022, 86, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avery, M.D.; Mathiason, M.; Andrighetti, T.; Autry, A.M.; Cammarano, D.; Dau, K.Q.; Hoffman, S.; Krause, S.A.; Montgomery, O.; Perry, A.; et al. Improved Self-Assessed Collaboration through Interprofessional Education: Midwifery Students and Obstetrics and Gynecology Residents Learning Together. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2022, 67, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martirosov, A.L.; Moser, L.R. Team-based Learning to Promote the Development of Metacognitive Awareness and Monitoring in Pharmacy Students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2021, 85, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, K.; Kulkarni, S.; Romaine, A.; Mange, D.; Little, C.; Cheng, I. Interprofessional student hotspotting: Preparing future health professionals to deliver team-based care for complex patients. J. Prof. Nurs. 2022, 38, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaimy, C.; Melton, B.; Davidson, G.; Persky, A.; Meyer, E. Availability of Didactic and Experiential Learning Opportunities in Veterinary Practice at US Pharmacy Programs. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2022, 86, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duck, A.A.; Stewart, M.W. A pedagogical redesign for online pathophysiology. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2021, 16, 362–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pence, P.L.; Franzen, S.R.; Kim, M.J. Flipping to Motivate: Perceptions Among Prelicensure Nursing Students. Nurse Educ. 2021, 46, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lybarger, K.; Ostendorf, M.; Yetisgen, M. Annotating social determinants of health using active learning, and characterizing determinants using neural event extraction. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021, 113, 103631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, B.D.; Oxley, M.S.; Chen, K.; Anksorus, H.; Hubal, R.; Persky, A.M.; Harris, S. A Concept Mapping Activity to Enhance Pharmacy Students’ Metacognition and Comprehension of Fundamental Disease State Knowledge. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2021, 85, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Sandoval, C.; Sibbald, S.; Ryan, B.L.; Orange, J.B. Interprofessional team-based geriatric education and training: A review of interventions in Canada. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2021, 42, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaine, K.P.; Dudaryk, R.; Milne, A.D.; Moon, T.S.; Nagy, D.; Sappenfield, J.W.; Teng, J.J. Training Anesthesiology Residents to Care for the Traumatically Injured in the United States. Anesth. Analg. 2023, 136, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acker, L.; Bova Campbell, K.; Naglee, C.; Taicher, B.; Bronshteyn, Y.S. Perioperative Management of Flecainide: A Problem-Based Learning Discussion. A&A Pract. 2021, 15, e01443. [Google Scholar]

- McCaffery, J.; Barrett, M.; Daingerfield, M.; Noivakowski, K.; Leckie, C. An Interprofessional Education (IPE) Experience with a Scaffolded Teaching Design. J. Allied Health 2023, 52, 75. [Google Scholar]