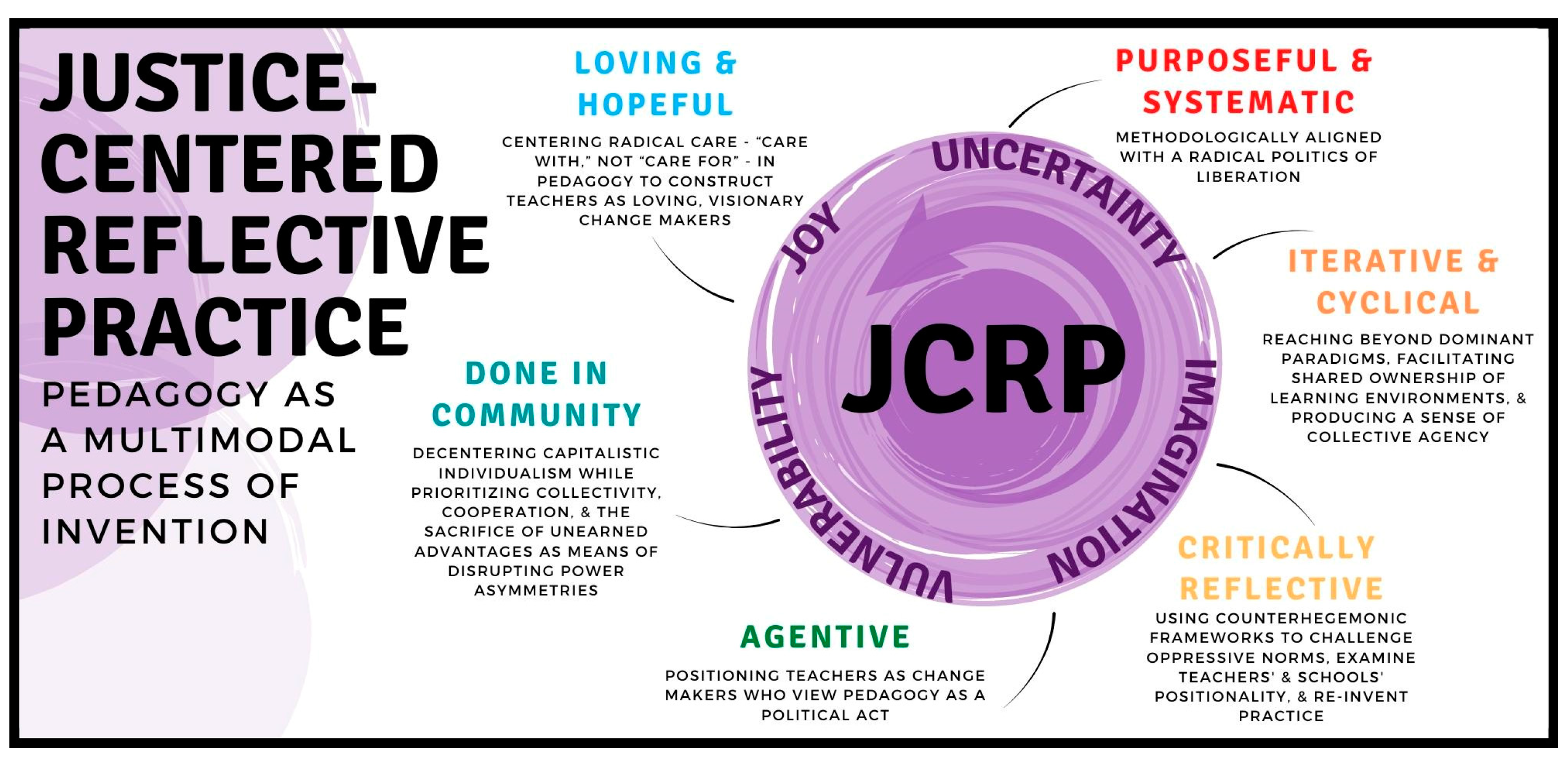

Threaded throughout these assumptions is the practice of advancing equity and inclusion as a multimodal pedagogical process—that is, we believe that using many modalities to engage with and produce knowledge, to interact with students and colleagues, and to negotiate shared understandings of teaching and learning is essential to the practice. In the sections below, we define each of these features of our approach, discuss how they are interrelated, and highlight the diverse scholarly literature and social movement traditions that have informed our thinking.

2.1. Developing Reflective Practice That Is Purposeful, Systematic, Iterative, and Cyclical

We draw on literature that views teacher development as an ongoing process of reflective practice and teachers as playing an important role in disrupting inequities. Justice-centered reflective practice positions teachers as producers of critical knowledge empowered to make classrooms sites of humanization and connection [

9], a task that is particularly challenging in a competitive, exploitative system of racial capitalism designed to alienate us from one another [

10]. Though the work of relationship building can sometimes seem chaotic and spontaneous, we approach this work in ways that are both strategic and systematic, and aimed at establishing a foundational ethos of connection and critical care [

11].

We embrace a vision of teacher education that rejects the idea of simply presenting novice teachers with a set of best practices that serve as shortcuts around the challenges of problem solving and engaging in introspection. Our approach stems from a belief that the best teachers, across the lifespan of teaching, ask questions of their practice and are ongoing learners of practice, learning from their teaching and from their students. One example of how this comes to life in our program is through a year-long inquiry project that our students engage in. As a part of the inquiry project, students select a certain aspect of their teaching practice to study in depth through the counter-hegemonic lenses that ground our curriculum. The inquiry project is also highly collaborative in nature, wherein our students participate in ongoing discussions about and reflections on their practice with their peers, mentor teachers, and instructors. Focusing on research and purposeful, ongoing, reflective practice invites novice and experienced teachers to practice a mindset—ways of doing and being—that cultivates inquiry as a stance through which they pose, address, and solve complex problems of practice to improve teaching and learning with ongoing attention to social justice means and ends [

6]. It centers teacher research and inquiry as a way to think about and practice teaching as a purposeful process of ongoing learning and reflection.

Here, the word “purposeful” has a double meaning, referring both to the intentionality discussed above and to the sense of purpose that guides our shared commitment to educational justice, a politics of liberation and a pedagogy of connection [

11] that requires ongoing presence, relational learning, and dialogue rather than reliance on the shortcuts ‘best practices’ supposedly offer [

4]. In this sense, embodying a learner-stance toward practice is deeply personal and political; it includes cultural humility toward our own biases and sources of privilege and a willingness to learn continually from the experiences of others [

7], along with a continual understanding that the personal journey of learning to teach as a “process of becoming” [

12] requires vulnerability and uncertainty.

We approach teacher education and a politics of liberation from the standpoint that injustice is institutional and systemic as well as individual and internalized. Thus, we operate under the premise that our pedagogy must embody a liberatory purpose in that it is fundamentally intersectional, centers students’ connection to liberation work, and builds on the work of justice-focused organizations outside of our school communities [

4]. We believe that justice-centered reflective practice has the potential to support teachers as reflective practitioners who account for and speak back to systemic and institutional injustice by employing critical, intersectional methodologies that disrupt colonial epistemologies.

As Esposito and Evans-Winters [

13] (p. 21) describe them, these intersectional qualitative methods enable an orientation that serves as “an epistemological stance and modus operandi for the examination (and interpretation) of (a) complex relationships, (b) cultural artifacts, (c) social contexts, and (d) researcher reflexivity”. In the tradition of other critical methodologists, their work names the way identity mediates our orientation to systematic qualitative exploration, as well as how we contribute to knowledge construction within our communities. Importantly, these critical methodologies create space for novice (and experienced) teachers to incorporate honest reflection and intentionality in teachers’ everyday practice, what Mendoza, Gutierrez, and Kirshner [

14] (p. ix) call “design as praxis”. They point to the power of designing learning environments as intentional interactional spaces that offer pathways to imagine possibilities across historical and time scales, calling this mediated praxis:

Mediated praxis… is the intentional organization of the learning environment—with attention to the moment-to-moment interactions and interconnectedness of larger social histories—toward equity, praxis, and transformative learning. This perspective requires attention to equity and transformative learning as both a process and outcome and must be attended to from conceptualization of the project and embedded throughout.

Central to our approach is this understanding of design as praxis; it is an intentional systematizing of inquiry in our practice. Prison abolitionist Miriame Kaba [

10] points out that, by design, social change involves trying out new things, taking risks, and often failing. In this way, she writes, the process—not some ideal final product—is the goal, and the process must be a co-creation driven by people’s real needs in a particular time and location, what Ayers [

9] (p. 81) calls “more a process of people in action than a finished condition”. Based on these assumptions, we hold onto a vision of liberatory teaching as aspirational, an ongoing process of creation and re-creation. Our approach to designing our curriculum is one that is iterative and responsive to the needs of our novice educator students and our school partners. We are intentional in co-constructing our classroom spaces, the texts and materials that we use, and our assessments through ongoing dialogue with and feedback from our students. In doing so, we take the stance that all members of our community can contribute valuable knowledge and expertise to conversations about schooling, teaching, and learning. This process, what Love [

4] refers to as “freedom dreaming”, requires imagination in order to lean into creating a new future for education. We argue that in this process being vulnerable and stepping into the uncertainty of not knowing what our new creation will be is what allows us to be in community with one another in ways that are meaningful, deeply connective, and transformative.

We make a conscious choice to lift up the wisdom and experience of Kaba [

10] and other social movement organizers, because we see classrooms as potential sites for profound social change and teachers as powerful agents of change, both within and outside of schools. In doing so, our approach attempts to position teachers, not as heroic individual change-makers, but as contributors to larger movements for social change that rely upon everyday work. Teachers have the power and responsibility to develop “authentic relationships of solidarity and mutuality” [

4] (p. 118), being supportive of and accountable to their school communities and to one another in the process of collectively grappling with what Cochran-Smith and Lytle [

6] call the ongoing “dialectic between theory and practice”. Social movement actors use this same idea to frame and learn from their social change practices. For example, Baptist and Rehmann [

15] (p. 7) advocate for a pedagogy that bridges the “false dichotomy between ‘theory’ and ‘praxis’”. Instead, they [

15] (p. 7) argue that in order to support a sense of collective agency among people who are working together to address the root causes of inequity, we should embrace “the concrete pedagogical task to combine different kinds and layers of knowledge and reflection that are currently separated and polarized in our prevailing education system”. These understandings of liberatory pedagogy speak to our concept of teacher inquiry as an iterative practice with the potential to produce critical knowledge of practice that is rooted in teachers’ own reflexivity, mutuality, and engagement in community.

Justice-centered reflective practice is based on the idea that teacher education should involve the cultivation of an inquiry stance toward practice, keeping questions about means and ends alive in the daily work of teaching and encouraging teachers to continue exploring whose (and what) interests are being served in any given moment of teaching [

6]. Our virtual instructional rounds, in which our students regularly video record themselves teaching and then debrief their teaching in small groups with their peers with an alumnus of our program as facilitator, speaks to how our students develop the skills to observe, reflect, and enact different teacher moves through an ongoing cycle of inquiry and praxis informed by liberatory theories. We contend that, though the stakes are always high in classrooms, the work toward liberation demands attention to what Kaba [

10] (p. 27) calls “a long view, understanding full well that [we are] just a tiny, little part of a story that already has a huge antecedent and has something that is going to come after that”. Informed by an extensive history of liberatory social movements, we take a long view of our work as justice-centered reflective practitioners.

2.2. Centering Critical Reflection

Teaching and learning always occur in sociopolitical contexts in the midst of histories of white supremacist exclusion. Learning to teach must include interdisciplinary exploration [

16] of these histories, the broader sociopolitical contexts of schooling, and the particular socio-political contexts within which teachers work. Baptist and Theoharis [

17] (p. 163) highlight the ways in which we have been deeply socialized to accept exploitative ideologies and dominant socio-political narratives, noting, “the process of education is at once one of uneducating and unlearning as well as one of educating and learning”. With this in mind, teachers need opportunities to name and critique injustice in order to transform curriculum and pedagogy so their classroom practice does not inadvertently reinforce biases and systems of domination [

4,

18,

19].

Love [

4] (p. 11) identifies the bold choice that confronts all teachers who choose to do this, asserting that “abolitionist teaching is choosing to engage in the struggle for educational justice knowing that you have the ability and human right to refuse oppression and refuse to oppress others, mainly your students”. To foster a critically reflective mindset, teacher education must center on the praxis mentioned above, joining theory and critical practice as a liberatory act [

20]. Novice teachers must have the opportunity to highlight and mine the connection between ideas learned in university settings and what is learned in life experiences as a necessary prerequisite for systematically challenging dominant, normative discourses and representations [

7] if they are to make a choice to engage in anti-oppressive teaching practices. Our program is organized into three curricular strands, one of them being the History and Social Context strand, where students reflect on the purposes of education, how those purposes are mediated through societal structures rooted in power asymmetries, and dominance at both the individual and institutional levels. Through readings, discussions, and assignments, students develop the skills to be critically reflective of their own practices and the culture of their schools, always with an eye towards equity, humanization, and liberation.

Justice-centered reflective practice conceives of critical reflection as involving both this outward-facing sociopolitical examination and an inward-looking exploration of identity and positionality. Teachers need opportunities to take into account and explore the multifaceted aspects of their own identities and conditions in order to understand how these facets of identity intersect [

21] in the context of racial capitalism and how they mutually constitute one another [

22]. All identity work involves particular attention to privilege and an interrogation of how identity is connected to the exercise of power as well as the uneven distribution of power in school contexts and in society writ large.

Again, the historic work of organizers offers insight into the relationship between identity, positionality, and our ability to imagine new possibilities for human connection. Ayers [

9] (p. xiii) names this as a key feature of the Freedom Schools of the 1960s, arguing that “freedom, if it means anything at all, points to the possibility of looking through your own eyes, of thinking, of locating yourself, and, importantly, of naming the barriers to your humanity, and then joining with others to move against those obstacles”. Similarly, Muhammad [

5] and Love [

4] also discuss how Freedom Schools and the continued resistance that Black people engage in within the field of education are part of a larger history of “freedom dreaming”, where joy is a central part of imagining a different future for education.

Price-Dennis and Sealey-Ruiz [

22] (p. 22) speak to the need for teachers to engage in an “archaeology of the self”, or “the self-exploration, probing, excavation, and understanding of where issues of race, racism, and human phobias live within individuals”. They [

22] (p. 23) identify three practices that are central to this process: questioning assumptions about race, engaging in critical conversations about race, and practicing reflexivity, “a cyclical process of (re)examining perceptions, beliefs, and actions relating to race”. For Ayers [

9] (p. 84), this kind of critical reflection is fundamentally an imaginative and vulnerable process. He calls for “a pedagogy of experience and participation, a pedagogy both situated in and stretching beyond itself, a critical pedagogy capable of questioning, rethinking, reimagining. We are looking for teaching that is alive and dynamic, teaching that helps students grapple with the question ‘Where is my place in the world?’”.

We believe that capturing the inward and outward-facing critical imaginations of both teachers and students cannot be simply done in the terrain of written language, because taking our minds and hearts beyond the bounds of the oppressive systems, structures, and cultural norms that define our world is not solely an intellectual exercise. Our approach rests on the assumption that, in order to reflect upon the harm we have (unevenly) experienced due to racial capitalism, we must notice how that harm shows up in our bodies and trace how it mediates our relationships [

23]. We must consider the physical, emotional, and relational implications of the social world we inhabit, making a connection between our own experiences of harm and the political economy of education (among other social institutions). This understanding is developed through multimodal exploration that allows us to use multiple senses and sensibilities to engage in this personal and collective “excavation” [

22]. We believe that the process of personal excavation—when done in community and through modalities that are typically not privileged in university spaces and are thus read as more “creative”—is one of mutual vulnerability, and also of uncertainty. An example of how personal excavation and multimodality intersect in our program curriculum is through teacher and learner self-autobiography and self-portrait. As part of this project, students are asked to reflect on their own educational experiences through the lenses of identity and power, sharing how these experiences may influence their understanding of and approach to teaching. The final product of this assignment is that students create self-portraits using a medium (or mediums) of their choice to represent their learner and emerging teacher identities. In the past, students have created collages, annotated music playlists, infographics, and photo essays as ways to capture their self-portrait. The students then share their self-portraits with each other in one of our class sessions.

Multimodality, then, serves several purposes, allowing us to broaden accessibility through different epistemologies and knowledge systems [

13] and create a learning environment in which novice teachers have multiply shaped invitations to critically examine their contexts, develop deeper understandings of their own positionality within those contexts, and to imagine a more just and equitable future [

24]. In a learning environment characterized by dynamic opportunities to imagine and engage multimodality, teachers gain access to expanded epistemologies and a range of means for self-authorship [

25], allowing for new opportunities as agentive sense-makers to re-make themselves, re-negotiate their identities as teachers, and re-imagine social futures [

26]. Multimodality, thus, can support teachers and help them to develop a praxis rooted in critical reflection, acknowledge their own responsibility and connection to a larger community, and develop an authentic accountability to the collective.

2.3. Living Justice in a Pedagogy of Agency, Community, Love, and Hope

Central to critical practice is teachers’ and students’ sense of individual and collective agency. Justice-centered reflective practice makes a commitment to centering opportunities for novice and experienced teachers to “read” and “re-read” the racialized world in which they live and work, which is essential in order for them to re-write and transform it [

27]. This work is both an act of what Santoro and Cain [

28] call “principled resistance”—rooted in thoughtfully constructed pedagogical, professional, and democratic principles—

and a critical reimagining of what education can be. We believe it is incumbent on teacher education programs to position preservice and novice teachers as agents of change who are responsible to the collective and able to interpret, understand, and transform the world around them, much like the Freedom Schools model of the 1960s [

9]. Freire’s [

27] work on “problem-posing education”, which envisions teaching and learning as mutually constitutive acts and defines teaching as a fundamentally human process based on human connection rather than a simple transference of knowledge, is a useful place to start envisioning what it looks like for teachers to embrace a sense of agency in all aspects of their work. One way that we lean into this stance is by incorporating Stevenson’s [

23] and Price-Dennis and Sealey-Ruiz’s [

22] conceptualization and skill-based practices of racial literacy. By using our class time to have students reflect on racialized messages that they received throughout their K-12 schooling, as well as providing opportunities for them to practice managing their racial stress and how to respond to racial conflict, we center humanity, human connection, and caring within teaching and within schools.

Justice-centered reflective practice reconceptualizes the act of teaching and prompts us to redefine what (and who) we believe teachers are. Designing university teaching and teacher education in ways that create space for participatory knowledge generation and sharing [

18] positions teachers not as technicians but as “transformative intellectuals” [

29] whose mutual work can advance change. This transformation, birthed out of the mutuality of human connection, is embodied in individual teachers’ internal processes as well as in the ways we reconfigure our professional relationships and disrupt dominant social hierarchies. Internally, teachers need to be able to engage in ongoing critical conversations that make them “better equipped to resist the rampant racist practices that disproportionately impact students of color” [

22] (p. 12) and, we would add, the emotional and intellectual violence that students of all marginalized identities inevitably face in school. In this way, teacher education programs can be fertile contexts for pre-service and novice teachers to develop professional relationships that are premised on mutual vulnerability and the humanizing of one another, substantive intellectual and emotional challenge, and deep connection with professional peers. We also see teacher education programs as spaces where teachers can find joy through being in close relationships with one another. These experiences can disrupt the highly individualistic cultural myth of teachers as self-made, i.e., the notion of “the natural teacher” [

12] (p. 230), and instead create opportunities to imagine a different type of teacher whose orientation is grounded in community, vulnerability, and love.

As teacher educators, we have the opportunity to develop a complex and deeply connected vision of community that can foster what hooks [

30] (p. 129) calls a “love ethic”, or the sense that our individual existence is dependent upon the existence of others in our community and around the world: “Communities sustain life—not nuclear families, or the ‘couple’, and certainly not the rugged individualist. There is no better place to learn the art of loving than in community”. Here, we are suggesting that teacher educators reject “society’s collective fear of love” [

30] (p. 91) and embrace a vision of love that permeates all our relationships, even the most difficult relationships that are mediated by histories of violence and inequity. Justice-centered teacher education re-shapes the teacher–student relationship, and, through a pedagogy of connection [

11], places a present, loving, relational care at the center of teaching and learning. Our program is structured so that our students have multiple layers of support throughout their teaching fellowship—they have their university instructors, their university advisers, their school-based mentors, and their program site directors, all who subscribe to a relational and student-centered orientation to teaching, mentoring, and learning through their curriculum, pedagogy, and practice.

This re-shaping is an intentional and visionary way of humanizing ourselves and the profession that shifts how we imagine what it means to be responsible to other teachers and learners in our professional community, disrupting systems of domination [

31] in real classrooms, in real time. This re-shaping of the teacher–student relationship also creates space for joy—making oneself “aware of [their] own humanity, creativity, self-determination, power, and ability to love abundantly” [

4] (p. 120). By finding joy in our connections with one another and the discovery of what can be possible when we work together collectively, we are resisting our own dehumanization and the internalization of oppressive structures and systems.

In their work with young Latinas, Figueroa and Fox [

31] (p. 238) argue that we must “work towards a critical care praxis not

in spite of our differences but

enabled by our differences”. They [

31] (p. 238) position “listening as critical care praxis [that] must start by listening to each other and reconciling difference without erasing it”. This concept of critical care implicitly critiques the “care for” model, which is premised on the assumption that those who are positioned to have more social power can know the needs and experiences of those with less social power. In contrast to this patronizing form of care, Figueroa and Fox suggest that listening authentically in a way that centers difference is essential to praxis. Their approach to qualitative research supports a vision of love that is both aimed toward social change and provides a blueprint for the kind of world we want to co-create.

Khan-Cullors [

32] (p. 148) also paints a picture of living out the liberatory values we advocate for in social justice movements. In describing the kinds of interpersonal relationships that support liberation work, she articulates the need “to love and honor the singular us along with the collective us”. This theme is taken up frequently in scholarship on social movements, which point to “prefigurative politics” as the intentional approach to interpersonal interactions within movement organizations that prefigure the kind of world movement actors are fighting for [

33]. There are many dimensions of interpersonal relationships that get renegotiated in movement work, but one key dimension that we see as particularly relevant to developing a teaching practice rooted in love is the recognition that in a deeply connected community we will all harm others and be harmed by others, thus we will all need to do the work of transforming harm [

10]. We view educational contexts as potential sites of individual and collective self-healing from the complex harms we experience as a result of the systems of domination in which we are all situated [

4].

Mirra’s [

34] (p. 7) conception of critical civic empathy, which is so deeply rooted in the intellectual work of critical literacy theorists, seems to be a call for us as teachers and teacher educators to develop deeply empathic connections with others as an important component of social change efforts:

Critical civic empathy is about more than simply understanding or tolerating individuals with whom we disagree on a personal level; it is about imaginatively embodying the lives of our fellow citizens while keeping in mind the social forces that differentiate our experiences as we make decisions about our shared future.

This conception of empathy as a tool for engaging in negotiations around complex sociopolitical issues reflects the notion of love—the “care, commitment, knowledge, responsibility, respect, and trust” [

35] (p. 133)—that is at the heart of justice-centered reflective practice. The approach we aspire to is a shared commitment to teaching and learning in the interest of all students and in the interest of disrupting the system of racial capitalism that shapes U.S. schooling and produces individual and generational trauma. It is rooted in a hopeful belief about the collective power and capacity of the mind, heart, and imagination to solve complex problems of educational practice and to advance equity and social change through the everyday work of teaching and learning. When we struggle, we are expressing optimism about the world as it could be and deriving joy and healing from the collective pursuit of imagining and creating the world we want. Love [

4] (p. 90) recognizes this as the “beauty in the struggle”. Our joy exists as an electric excitement of possibility in moments of sociopolitical struggle, because these are moments when we are consciously resisting the impulse to be crushed and dehumanized by the limitations of the world as it is, instead choosing to find joy, connection, and inspiration in the possibilities we imagine and create together.

Teachers are in a unique position to help foster communities of hope, joy, and transformation by remaining in a constant state of creativity and imagination, always building what we want for ourselves and nurturing the conditions for love and connection in our classrooms. Justice-centered reflective practice constructs teaching as a joyful, fundamentally relational act that is embodied in what Rodgers and Raider-Roth [

36] describe as “presence”. In this way, counter-hegemonic teaching is not simply

against injustice, it is

for positive action. It holds that by centering loving connection and radical hope alongside noticing systems of domination and exploitation, we can proactively imagine and create an alternative world.

In capitalist systems, hopefulness is often portrayed as an impractical or improbable desire, an unreasonable demand to control forces beyond our purview. However, justice-centered reflective practice relies on the notion that we must “demand the impossible” [

4] (p. 7) in order to do work that matters to marginalized communities. Far from being unreasonable, impractical, or improbable, this enactment of radical hope should be a reflection of our optimistic belief in one another to rise to our potential as agents of social change as well as our trust in one another to confront the interpersonal challenges that can obstruct our sense of connection and ability to act [

10]. Kaba [

10] (p. 27) describes hope as a discipline and reminds us that

We have to practice it every single day. Because in the world we live in, it’s easy to feel a sense of hopelessness, that everything is all bad all the time, that nothing is going to change ever, that people are evil and bad at the bottom. It feels sometimes that it’s being proven in various different ways, so I really get that. I understand why people feel that way. I just choose differently. I choose to think a different way, and I choose to act in a different way. I choose to trust people until they prove themselves untrustworthy.

When teacher educators choose to think and act “a different way”, pre-service or novice teachers are given the green light to practice the discipline of hope, enact joy, and live into their imagination, which inevitably shapes their students’ learning. As teacher educators, we do this not out of obligation, but with the purpose of feeling whole and connected with others. We do this because we feel moved to seek out this connection in our teaching practice, and when we are engaging in critical care we too benefit from the love, trust, and intellectual and emotional vulnerability that form the basis of this mutuality. Justice-oriented reflective practice offers us the means to remain accountable to one another while also maintaining our human connection.

Communities in which members are reciprocally accountable to each other can challenge individuals to stretch beyond dominant assumptions while also helping us collectively challenge the structures of domination around us [

10]. This intersection of mutuality and accountability through a stance of critical care creates possibility. In the context of a teacher education program, facilitating what Cochran-Smith and Lytle [

6] call “inquiry communities” across a school/university partnership—or placing teaching in community to generate knowledge about complex problems of practice—expands the reach of justice-centered efforts in education and lives into a pedagogy of connection. It is a counter-individualistic means of re-shaping public discourse about education in and outside of schools [

6]. It also disrupts the hierarchies that typically define the relationship between schools and universities and limit our ability to learn from knowledge that is generated outside the ivory tower. Far from devaluing the work of university-based teacher education programs, this approach extends the possibilities that open up as we invite more voices into our broader professional conversations.