Leaders’ Social and Disability Justice Drive to Cultivate Inclusive Schooling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Leadership for Social Justice

[Make] issues of race, class, gender, disability, sexual orientation, and other historically and currently marginalizing conditions in the United States central to their advocacy, leadership practice, and vision. This definition centers on addressing and eliminating marginalization in schools. Thus, inclusive practices for students with disabilities, English language learners (ELLs), and other students traditionally segregated in schools are also necessitated by this definition.(p. 223)

2.3. Disability Studies in Education

3. Research Methods

3.1. Study Context

3.2. Recruitment Procedures

- (1)

- Employed in a public school district;

- (2)

- Member of the district-level administration responsible for special education. Given the range of state special education administration credential requirements [63], it is important to note that participants held a variety of titles;

- (3)

- Evidence of a strong commitment to inclusive education, as indicated by A or B below:

- Provides leadership for a district that has a publicly stated inclusive commitment (e.g., on a district website, in the district goals or vision statement, or in a district newsletter that is posted in a public online space);

- Demonstrates strong personal commitment for inclusive education, as measured by positive indicators on the Inclusion Survey [64];

- (4)

- Evidence of Inclusive Education in Action, as indicated by A, B, or C below:

- Provides leadership for a district that is inclusive of students with disabilities, meaning that schools educate students with disabilities in their home school;

- Provides leadership for a district that predominately educates students with disabilities in general education classrooms, with no students placed in separate special education classrooms for a majority of the day, using the principle of natural proportions. This means that students with disabilities should be placed in schools and classrooms in natural proportion to the occurrence of disability in that district [65];

- Provides leadership for a district that is taking tangible steps toward inclusive education.

3.3. Participants

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis

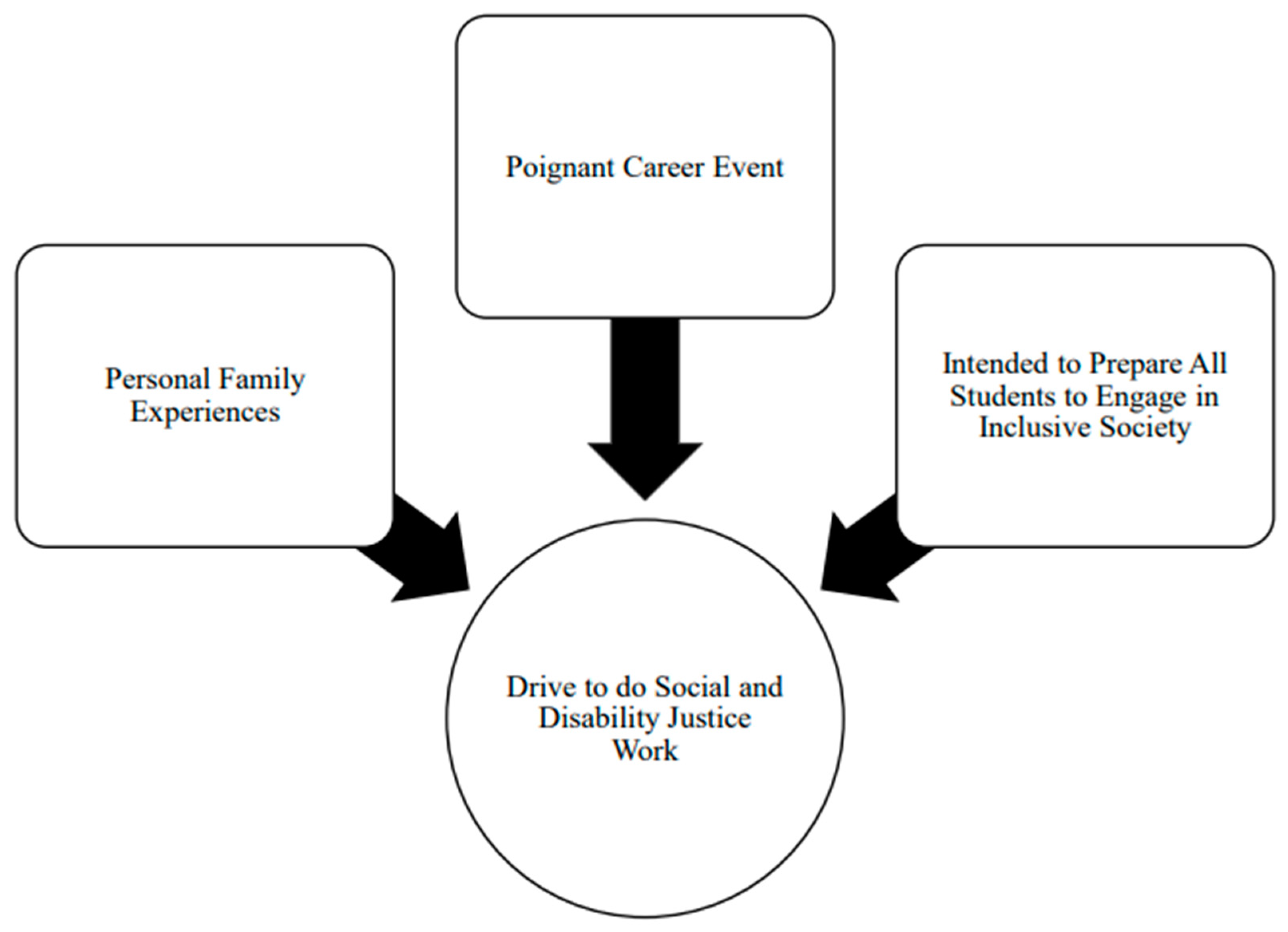

4. Results: Participants’ Drive to Carry out Social Justice Work in the Field of Inclusive Education

[She] had a philosophical shift…. A complete change in the way that I saw … how I felt philosophically, about how we were servicing students with disabilities. So when I had that philosophical shift and I realized, oh my … you know, this is a civil rights issue. We are doing a disservice to these kids. They have rights and we’re not giving them access to what they have the rights of access to.

This is our generation, my generation’s civil rights issue. There’s still a large school of thought that we should be segregating students with certain disabilities. I feel very strongly that it is fundamentally wrong. It is as wrong as segregating students with a different ethnicity or by race. I disagree with it. I’m hoping that we’re raising a generation of children in our school system that, as they grow up as adults, won’t tolerate that any more than our generation would tolerate discrimination because of race. But, it is still, I would say, it is still the minority who feel the way that I do. The majority feel that students [with disabilities] should be separated.

We met a lot of people with disabilities in and out of our home as a kid. I grew up in the 1970s. My parents were kind of like hippies. Crazy world. They were always bringing home stray dogs and stray kids. So even [when I was] a child, my siblings and I were never really … people with disabilities were just welcomed. My parents didn’t instill any type of knowledge … we were never told they were different. My parents had the perspective that people with disabilities had to be treated like everybody else. So, I was ingrained with that thinking as a child.

My personal perspective is that we all share the planet. I mean school, to me, is just preparation for what is on the other side, which is the real world.… I do not believe in segregated programming at all because it does not mirror the real world. But I do think that … because, you know, the bottom line is these people with disabilities … we all are members of the human race. And, we all live in the same fish bowl. So, we all have to learn how to live in the same fish bowl.

I think the roots of my interest in educational equity for children with disabilities goes back to my adolescence. I grew up in a Quaker family. And, I had some experiences as a teenager working at a Quaker summer program that focused on disenfranchised groups of people: a visit to an institution where people with developmental disabilities were living, in what seemed to me to be appalling conditions. The fear I felt of the people who lived there and their subsequent kindness and welcome to me were actually life changing. I was also fortunate to attend a university special education program that had a strong social justice focus.

We accept the responsibility for the success of every student. That’s what we are able to do and so we mean every student, you know, literally every student. A big thing for us is that inclusion is a philosophy, it is the way we see our kids. It’s not a program. When we say we’re fully inclusive, what we mean by that is our students attend the same schools that they would attend if they did not have a disability. They are in the same classes that they would be in if they did not have a disability. It does not mean that students spend one hundred percent of their time in the regular classroom, never leaving there for any specialized instruction. I mean kids, even kids without disabilities, if they need some individualized instruction in something can go out with a teacher to get that. And special education students are no different from that. So for us, it means that everybody has the same access. It doesn’t mean the percentage of time that you sit at a desk in a regular classroom.

I think for me and for a lot of us is the idea of the neighborhood school that is designed to meet the needs of the children that live in the attendance area. That’s the core of it. So the idea is that children should be able to go to school with their neighbors near their homes and it is the responsibility of the school system to provide the resources that the kids who live in the attendance area need to be successful at school. And by doing that, it means our kids all attend their neighborhood schools. And so that that means we’re dealing with a natural population of students in our school. So we don’t have individual schools who have an overwhelming number of students with severe disabilities or overwhelming number of kids with problem behaviors because they’re getting bused here.

I am a firm believer that every child needs to be honored, respected, and taught in school. I have a very profound respect for students and their parents, students with disabilities and their parents of students with disabilities. I just came to respect what they were up against. I love all kids. I’ve never met a kid that I didn’t like. And that was just me. But working with families when they had a child with disabilities, I just came to respect them and their hard work and their desires to have their children be respected and honored.

In working with students with disabilities, I realized how they were smart, engaging, and funny. They were typical kids who had to deal with things they had no control over. And why wouldn’t somebody respect a kid for that? I mean I saw kids with disabilities doing things that I would not have the gumption to do that had I been in their shoes. And it just made me think they need the very best that we can give them. That is my guiding principle.

It is rooted in our system of collectively being responsible for teaching all of the students that come through the door. We’re responsible for providing access to the curriculum and having an expectation that all kids meet progress levels.

I have a social justice perspective about where we are going. We are going to close the gap between students who struggle and students with disabilities. I think that one of the things that is interesting is that we all pay a lot of attention sometimes to the poverty issue, and when it comes to the disability issue there is still this underlying belief that well we can’t really expect those kids to make progress because after all, they haven’t the capacity, or something like that. So that’s why in my mind, I like the disability piece because I think it’s under … it’s not as big of a focus problem in a lot of districts. Lots of people talk about poverty, everybody knows that we have a poverty gap, and we are and I believe, very strongly, that that is necessary. I try to bring that same level of urgency to kids with disabilities.

I am fully committed to inclusive districts. I guess I have two sons that tell me. They don’t have special education churches and special education malls. I think, why should this be any different? All kids are diverse from each other, and so kids need to learn from each other in inclusive communities.

5. Discussion of Social and Disability Justice Roots

We’re an inclusive system, which to us means that all students should have equal access to programs in their neighborhood schools with their age appropriate peers. So what we believe as a district is that every student should have access to every program that our system has to offer without having to go somewhere else to get it. So they participate in their neighborhood schools with their age appropriate peers.

6. Implications for Teacher Education Classrooms and Spaces

7. Limitations and Future Research

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sailor, W. Equity as a basis for inclusive educational systems change. Australas. J. Spec. Educ. 2017, 41, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharis, G.; Causton, J.; Tracy-Bronson, C.P. Inclusive reform as a response to high-stakes pressure? Leading toward inclusion in the age of accountability. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2016, 118, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMatthews, D.; Mawhinney, H. Social justice leadership and inclusion: Exploring challenges in an urban district struggling to address inequities. Educ. Adm. Q. 2014, 50, 844–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentith, A.; Frattura, E.; Kaylor, M. Reculturing for equity through integrated services: A case study of one district’s reform. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2013, 17, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryndak, D.; Reardon, R.; Benner, S.; Ward, T. Transitioning to and sustaining district-wide inclusive services: A 7-year study of a district’s ongoing journey and its accompanying complexities. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2007, 32, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy-Bronson, C.P. District-level inclusive special education leaders demonstrate social justice strategies. J. Spec. Educ. Leadersh. 2020, 33, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Cosier, M.; Causton-Theoharis, J.; Theoharis, G. Does access matter? Time in general education and achievement for students with disabilities. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2013, 34, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.; Cosgriff, J.C.; Agran, M.; Washington, B.H. Student self-determination: A preliminary investigation of the role of participation in inclusive settings. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 2013, 48, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, S.; Moller, J.; Zimmermann, F. Inclusive education of students with general learning difficulties: A meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2021, 91, 432–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, J.A.; Mastergeorge, A.M. Academic and cognitive profiles of students with autism: Implications for classroom practice and placement. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2010, 25, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.R.; O’Brian, M. Many hats and a delicate balance. J. Spec. Educ. Leadersh. 2007, 20, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Boscardin, M.L.; McCarthy, E.; Delgado, R. An integrated research-based approach to creating standards for special education leadership. J. Spec. Educ. Leadersh. 2009, 22, 68–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pazey, B.L.; Cole, H.A. The role of special education training in the development of socially just leaders: Building an equity consciousness in educational leadership programs. Educ. Adm. Q. 2012, 49, 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMatthews, D. Make sense of social justice leadership: A case study of principal’s experiences to create a more inclusive school. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2015, 14, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPaola, M.F.; Walther-Thomas, C. Principals and Special Education: The Critical Role of School Leaders; Center on Personnel Studies in Special Education: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppey, D.; McLeskey, J. A case study of principal leadership in an effective inclusive school. J. Spec. Educ. 2013, 46, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyler, C.; Fuentes, C. Leadership in rich learning in high-poverty schools. J. Spec. Educ. Leadersh. 2012, 25, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Theoharis, G. The School Leaders Our Children Deserve; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, N.L.; McLeskey, J.; Redd, L. Setting the direction: The role of the principal in developing an effective, inclusive school. J. Spec. Educ. Leadersh. 2011, 24, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chism, D.T. Leading Your School toward Equity: A Practical Framework for Walking the Talk; Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Diem, S.; Welton Anjalé, D. Anti-Racist Educational Leadership and Policy: Addressing Racism in Public Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, P.A. Becoming an Antiracist School Leader: Dare to Be Real; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, P.; Swalwell, K.M. Fix Injustice Not Kids and Other Principles for Transformative Equity Leadership; Association for Curriculum and Development: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings, G.C.; Reed, D.S. Getting into Good Trouble at School: A Guide to Building an Antiracist School System; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, G.S.; Richardson, J. Equity Warriors: Creating Schools That Students Deserve; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-McCutchen, R.L. Radical Care: Leading for Justice in Urban Schools; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan, M. Navigating Social Justice: A Schema for Educational Leadership; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, M. Public School Equity: Educational Leadership for Justice; National Geographic Books: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Theoharis, G. Social justice educational leaders and resistance: Toward a theory of social justice leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 2007, 42, 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, M.R.; Lindstrom, L.; Yovanoff, P. Improving graduation and employment outcomes of students with disabilities: Predictive factors and student perspectives. Except. Child. 2000, 66, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E.W.; Hughes, C. Increasing social interaction among adolescents with intellectual disabilities and their general education peers: Effective interventions. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2005, 30, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimera, R.E. The national cost-efficiency of supported employees with intellectual disabilities: The worker’s perspective. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2010, 33, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.; Meyer, L. Development and social competence after two years for students enrolled in inclusive and self-contained educational programs. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2002, 27, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Test, D.W.; Mazzotti, V.L.; Mustian, A.L.; Fowler, C.H.; Kortering, L.; Kohler, P. Evidence-based secondary transition predictors for improving postschool outcomes for students with disabilities. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 2009, 32, 160–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.T.; Wang, M.C.; Walberg, H.J. The effects of inclusion on learning. Educ. Leadersh. 1994, 52, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Carlberg, C.; Kavale, K.A. The efficacy of special versus regular class placement for exceptional children: A meta-analysis. J. Spec. Educ. 1980, 14, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, C.M.; Waldron, N.; Majd, M.; Hasazi, S. Academic progress of students across inclusive and traditional settings. Ment. Retard. 2004, 42, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hehir, T.; Katzman, L. Effective Inclusive Schools: Designing Successful Schoolwide Programs; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Oh-Young, C.; Filler, J. A meta-analysis of the effects of placement on academic and social skill outcome measures of students with disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 47, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szumski, G.; Karwowski, M. Psychosocial functioning and school achievement of children with mild intellectual disability in polish special, integrative, and mainstream schools. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2014, 11, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.C.; Baker, E.T. Mainstreaming programs: Design features and effects. J. Spec. Educ. 1985, 19, 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Education. 44th Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Action, 2022; United States Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- DeMatthews, D.E.; Kotok, S.; Serafini, A. Leadership preparation for special education and inclusive schools: Beliefs and recommendations from successful principals. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2019, 15, 303–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharis, G. Disrupting injustice: Principals narrate the strategies they use to improve their schools and advance social justice. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2010, 112, 331–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M.; Sandill, A. Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organisational cultures and leadership. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2010, 14, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causton-Theoharis, J.; Theoharis, G.; Bull, T.; Cosier, M.; Dempf-Aldrich, K. Schools of promise: A school district—University partnership centered on inclusive school reform. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2011, 32, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, N.; McLeskey, J. Establishing a collaborative school culture through comprehensive school reform. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 2010, 20, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambron-McCabe, N.; McCarthy, M. Educating school leaders for social justice. Educ. Policy 2005, 19, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, H. Five Essential Components for Social Justice Education. Equity Excell. Educ. 2005, 38, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogotch, I.E. Educational leadership and social justice: Practice into theory. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2002, 12, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, K.P.; Grinberg, J. Leadership for social justice: Authentic participation in the case of a community center in Caracas, Venezuela. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2002, 12, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.; Ward, M. “Yes, but...”: Education leaders discuss social justice. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2004, 14, 530–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, J. Leadership for socially just schooling: More substance and less style in high risk low trust times? J. Sch. Leadersh. 2002, 12, 198–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMatthews, D. Dimensions of social justice leadership: A critical review of actions, challenges, dilemmas, and opportunities for the inclusion of students with disabilities in U.S. schools. Rev. Int. Educ. Para Justicia Soc. (RIEJS) 2014, 3, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danforth, S.; Gabel, S.L. Vital Questions Facing Disability Studies in Education; Peter Lang Publishing: Frankfurt, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, D.J. The natural hierarchy undone: Disability studies’ contributions to contemporary debates in education. In Vital Questions Facing Disability Studies in Education; Danforth, S., Gabel, S.L., Eds.; Peter Lang Publishing: Frankfurt, Germany, 2006; pp. 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare, T. The social model of disability. In Disability Studies Reader; Davis, L.J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). PL 108-446. 20 U.S.C. 1400 et seq. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Waitoller, F.R.; Artiles, A.J.; Cheney, D.A. A review of overrepresentation research and explanation. J. Spec. Educ. 2010, 44, 20–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosp, J.L.; Reschly, D.J. Referral rates for intervention or assessment: A meta-analysis of racial differences. J. Spec. Educ. 2003, 37, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, R.C.; Biklen, S.K. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods, 5th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Boscardin, M.L.; Weir, K.; Kusek, C. A National Study of State Credentialing Requirements for Administrators of Special Education. J. Spec. Educ. Leadersh. 2010, 23, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Praisner, C.L. Attitudes of elementary school principals toward the inclusion of students with disabilities. Except. Child. 2003, 69, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causton, J.; Tracy-Bronson, C.P. The Speech-Language Pathologist’s Handbook for Inclusive School Practices; Paul H. Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, J.; Mabokela, R. Leadership challenges in addressing changing demographics in schools. NASSP Bull. 2014, 98, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusch, P.I.; Ness, L.R. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.; di Gregorio, S. Digital tools in qualitative analysis. In Qualitative Inquiry and Global Crisis; Denzin, N.K., Giardina, M.D., Eds.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mawhinney, L. Making our way: Rethinking and disrupting teacher education. Special Issue Call. Educ. Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Causton, J.; Theoharis, G. Creating inclusive schools for all students. Educ. Dig. 2009, 74, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Boscardin, M.L. The administrative role in transforming secondary schools to support inclusive evidence-based practices. Am. Second. Educ. 2005, 33, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, J. Leading special education in an era of systems redesign: A commentary. J. Spec. Educ. Leadersh. 2012, 25, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dodman, S.L.; DeMulder, E.K.; View, J.L.; Swalwell, K.; Stribling, S.; Ra, S.; Dallman, L. Equity audits as a tool of critical data-driven decision making: Preparing teachers to see beyond achievement gaps and bubbles. Action Teach. Educ. 2019, 41, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrla, L.; Scheurich, J.J.; Garcia, J.; Nolly, G. Equity audits: A practical leadership tool for developing equitable and excellent schools. Educ. Adm. Q. 2004, 40, 133–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M.; Lytle, S. Beyond certainty: Taking an inquiry stance on practice. In Teachers Caught in the Action: Professional Development that Matters; Lieberman, A., Miller, L., Eds.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, P.C.; Swalwell, K. Equity literacy for all. Educ. Leadersh. 2015, 72, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nusbaum, E.A.; Lester, J.N. Critical disability studies and diverse bodyminds in qualitative inquiry. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 6th ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Giardina, M.D., Cannella, G.S., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, H.; Dickens, B. (Re)framing qualitative research as a prickly artichoke: Peeling back the layers of structural ableism within the institutional research process. In Centering Disability in Critical Qualitative Research; Lester, J.N., Nusbaum, E.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lashley, C.; Boscardin, M.L. Special education administration at a crossroads: Availability, licensure, and preparation of special education administrators. J. Spec. Educ. Leadersh. 2003, 16, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Capper, C.A.; Frattura, E.M. Meeting the Needs of Students of All Abilities: How Leaders Go Beyond Inclusion, 2nd ed.; Corwin: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Irby, D.J. Stuck Improving: Racial Equity and School Leadership; Harvard Education Press: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Leader | Age Range | Race | Gender | Years of Special Education Teaching Experience | Years of Administrator Experience | State | Position in District |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Kora | 51–60 | W | F | 7–12 | 20 | VA | Coordinator of Positive Behavior Support |

| 2. Mia | 31–40 | W | F | 7–12 | 6 | VT | Director of Student Support Services |

| 3. Sophie | 61 or more | H | F | 12 | 20 | CA | Director of Special Education |

| 4. Lucy | 31–40 | W | F | 14 | 9 | VA | Supervisor of Special Education |

| 5. Miller | 61 or more | W | M | 15 | >9 | AZ | Director of Student Services |

| 6. Charlotte | 31–40 | W | F | 0 | 8 | MD | Associate Superintendent, Education Services |

| 7. Leah | 31–40 | W | F | 4 | 7 | VT | Special Education Director |

| Leader | Total Students | Grades | Percentage of Students with IEPs in the District | Students Who Qualify for Free or Reduced-Price Lunch | ELL Students | Students of Color | Percentage of Students with IEPs that are Included in General Education Classrooms at Least 75% of the Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Kora | 9533 | K-12 | 10% | 38% | 2.7% | 6% Asian 4% African American 3% Hispanic 1% Other 86% White | 81–100% |

| 2. Mia | 4052 | K-12 | 11.3% | 14% | 2.7% | 9% as African American, Asian, or Hispanic 91% White | 61–80% |

| 3. Sophie | 132,000 | Pre-K to 12th | 11.2% | 59.4% | 26.5% | 46% Hispanic 23.4% White 10.2% African American 5.4% Filipino 4.9% Indo-Chinese 3.3% Asian 0.3% Native American 0.6% Pacific Islander 5.4% Multi Racial/Ethnicity | N/A |

| 4. Lucy | 9500 | K-12 | 10% | 38% | N/A | 6% Asian 4% African American 3% Hispanic 1% Other 86% White | 81–100% |

| 5. Miller | 34,149 | Pre-K to 12th | 8.1% | 29.97% | 1.6% | 18% Hispanic 4% Asian 3% Black 1% Native American 3% Two or More Races 71% White | 81–100% |

| 6. Charlotte | 15,963 | Pre-K-12 | 14.7% | 43.95% | 1.3% | 2.2% Asian, 27.3% African American, 12.8% Hispanic, 48.1% White, 9.6% Other | 84.5% |

| 7. Leah | 1212 | Pre-K to 8th grade | 13% | 20% | 3% | 3% Asian, 2% African American, 0% Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 92% White, 2% Other | 89% |

| Tell me about your advocacy throughout the district. Talk about your commitment to inclusive education. Where did your commitment to inclusion come from? Can you tell me about a time when you had to take a strong stand on something? |

| What are you most committed to as a leader? |

| Talk about access and equity, and what it means in your leadership context. What were your early experiences with individuals with disabilities? How did your early experiences shape your leadership today? |

| How would you describe your leadership? |

| Findings | Synopsis of Results | Impact on Disrupting and Reimagining the Field of Education |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Family Experiences | Leader’s parents brought students with disabilities into their childhood home and had the perspective that people with disabilities had to be treated like everybody else Leader’s parents ran summer camp programs for children who were economically disadvantaged Experienced, as a teenager, working at a summer program that focused on “disenfranchised groups of people”: visited an institution where people with developmental disabilities were living | Early memories of equality of treatment for individuals with disabilities and that various socioeconomic statuses have lifelong justice implications Hands-on experience at community programs that work with cohorts of marginalized people based on economic status, disability, living conditions, etc. at a young age was influential in noticing unjust systems and conditions in schools |

| Poignant Career Events | A directive from an administrator allowed her to see that how students with disabilities are serviced is a civil rights issue Inclusion is “a civil rights issue intersecting with the social justice issue”; “it’s all about leveling the playing field. It’s all about providing people with free, fair access that is based on what they need”. Lack of access to general education means “not giving [students] access to what they have the rights of access to” Segregating students with certain disabilities is as wrong as discrimination based on race and ethnicity Self-contained classroom teaching job where students with emotional behavioral disability were not allowed to eat in the cafeteria and instead were mandated to eat in windowless classrooms; let others know that this practice was unfair, unhealthy, and discriminatory Has a social justice perspective about where we are going, bringing the same urgency to disability as the conversation around poverty and the academic gap; very strong collective social justice core | Knowledge of disability justice as a civil rights issue Understanding the connection between civil rights, social justice, and disability justice Creating equitable opportunities starts with small changes, using justice as the orienting mindset from which to operate Access to general education is based on legal rights (LRE principle under IDEA) Segregation based on dis/ability should not be widely accepted in schools Understanding the connection between disability and race as sites of segregation and injustice Advocating for injustices within their local contexts The social justice perspective means analyzing the gaps in achievements along multiple identity lines, such as with socioeconomic and disability Collective social justice core guides actions, at the district level |

| Intention to Prepare Students to Engage in Inclusive Society | Does not believe in segregated programs at all because it does not mirror the real world; all live in the same fish bowl; there’s no special education churches and special education malls | Inclusive settings provide optimal preparation for the real world. Schools should represent the diversity of multiple identities, as should community organizations like churches and malls. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tracy-Bronson, C.P. Leaders’ Social and Disability Justice Drive to Cultivate Inclusive Schooling. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14040424

Tracy-Bronson CP. Leaders’ Social and Disability Justice Drive to Cultivate Inclusive Schooling. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(4):424. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14040424

Chicago/Turabian StyleTracy-Bronson, Chelsea P. 2024. "Leaders’ Social and Disability Justice Drive to Cultivate Inclusive Schooling" Education Sciences 14, no. 4: 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14040424

APA StyleTracy-Bronson, C. P. (2024). Leaders’ Social and Disability Justice Drive to Cultivate Inclusive Schooling. Education Sciences, 14(4), 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14040424