Musical Instrumental Self-Concept, Social Support, and Grounded Optimism in Secondary School Students: Psycho-Pedagogical Implications for Music Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement Variables and Tools

3. Procedure and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Correlations

4.1.1. Grounded Optimism

4.1.2. Perceived Social Support

4.1.3. Musical Instrumental Self-Concept

4.1.4. Correlations

4.2. Regressions

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vispoel, W.P. The development and validation of the Arts Self-Perception Inventory for Adults. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1996, 56, 719–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruismaki, T.; Tereska, T. Early childhood musical experiences: Contributing to pre-servive elementary teachers’ self-concept in musical and success in music education (during student age). Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2006, 14, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavelson, R.J.; Hubner, J.J.; Stanton, G.C. Validation of construct interpretations. Rev. Educ. Res. 1976, 46, 407–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vispoel, W.P. Measuring and understanding self-perceptions of musical ability. In International Advances in Self Research; Marsh, H., Craven, R., McInerney, D., Eds.; IAP: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2003; pp. 151–179. [Google Scholar]

- Degé, F.; Wehrum, S.; Stark, R.; Schwarzer, G. Music lessons and academic self concept in 12- to 14-year-old children. Music. Sci. 2014, 18, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamero, I. Beneficios Extramusicales de la Música: Inteligencia Emocional y Autoconcepto. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 2021. Available online: https://webges.uv.es/public/uvEntreuWeb/tesis/tesis-1687998-GDUJP790V1MSPN6V.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Oriola, S.; Gustems, J.; Navarro, M. La educación musical: Fundamentos y aportaciones a la neuroeducación. J. Neuroeduc. 2021, 2, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guhn, M.; Emerson, S.D.; Gouzouasis, P. A population-level analysis of associations between school music participation and academic achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 112, 308–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.P. Relations among motivation, performance achievement, and music experience variables in secondary instrumental music students. J. Res. Music. Educ. 2005, 53, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P.; Liu, M.Y. Psychological needs and motivational outcomes in a high school orchestra program. J. Res. Music. Educ. 2018, 67, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, G.E.; Osborne, M.S.; Barrett, M.S.; Davidson, J.W.; Faulkner, R. Motivation to study music in Australian schools: The impact of music learning, gender, and socio-economic status. Res. Stud. Music. Educ. 2015, 37, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatt, M.D. The Music Practice Motivation Scale: An exploration of secondary instrumental music students’ motivation to practice. Int. J. Music. Educ. 2023, 41, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granada, J.; Cortijo, A.; Alemany, I. Validación de un cuestionario para medir el autoconcepto musical del alumnado de grado básico y profesional de conservatorio. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 10, 1409–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Blanco, S. Motivación Académica y Autoconcepto Musical del Alumnado de Enseñanzas Superiores de Música. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universidad de Vigo, Vigo, Spain, 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11093/3056 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Blanco, S.; Dominguez, S.; Pino, M. Autoconcepto musical y clima motivacional del alumnado de los conservatorios profesionales de música de Pontevedra. In Proceedings of the XV Congreso Internacional Gallegoportugués de Psicopedagogía: II Congreso de la Asociación Científica Internacional de Psicopedagogía, Coruña, Spain, 4–6 September 2019; pp. 1010–1021. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2183/23486 (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Zubeldia, M.; Díaz, M.; Goñi, E. Autoconcepto, atribuciones causales y ansiedad rasgo del alumnado de conservatorio. Diferencias asociadas a la edad y al género. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2018, 10, 79–102. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10835/5927 (accessed on 7 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Díaz, E.; Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Ros, I.; Antonio-Agirre, I. Implicación escolar y autoconcepto multidimensional en una muestra de estudiantes españoles de secundaria. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2017, 28, 1103–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Ramos-Díaz, E.; Ros, I.; Fernández-Zabala, A.; Revuelta, L. Bienestar subjetivo en la adolescencia: El papel de la resiliencia, el autoconcepto y el apoyo social percibido. Suma Psicol. 2017, 23, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J. The relationship of music self-esteem to degree of participation in school and out-of-school music activities among upper elementary students. Contrib. Music. Educ. 1990, 17, 20–31. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24127467 (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Royo, F. Optimismo, Rendimiento Académico y Adaptación Escolar. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, A. Estilos de Vida Activa y Saludable, Salud Física y Mental, Personalidad y Rendimiento Académico en Adolescentes. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain, 2016. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10366/129708 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Sánchez-Hernando, B.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Gea-Caballero, V.; Carboneres-Tafaner, M.I.; Ferrer-Gracia, E.; Gasch-Gallén, Á. Healthy lifestyle and academic performance in middle school students from the region of Aragón (Spain). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, D.G.; Burland, K.; Davidson, J.W. The social context of musical success: A developmental account. Br. J. Psychol. 2003, 94, 529–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, O.; Zarza-Alzugaray, F.J.; Cuartero, L.M.; Orejudo, S. General Music Self-Efficacy Scale: Adaptation and validation of a version in Spanish. Psychol. Music. 2022, 51, 838–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buendía, L.; Colás, P.; Hernández, F. Métodos de Investigación en Psicopedagogía; McGraw Hill Ed.: Madrid, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zarza-Alzugaray, B. Autoconcepto Musical Instrumental y Variables Relacionadas en Estudiantes de Secundaria. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 2024. (Forthcoming). [Google Scholar]

- Cuartero, L.M. Autoeficacia Musical y Variables Relacionadas en Estudiantes de Conservatorio: Adaptación de Dos Cuestionarios y Estudio Correlacional. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 2018. Available online: https://zaguan.unizar.es/record/77061/files/TESIS-2019-039.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Tourón, J.; Lizasoain Hernández, L.A.; Navarro-Asencio, E.A.; López González, E. Análisis de Datos y Medida en Educación; UNIR Editorial: Logroño, Spain, 2023; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, A.; Ruiz, M.A. Análisis de Datos con SPSS 13 Base; McGraw Hill Ed.: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zubeldia, M.; Goñi, E.; Díaz, M.; Goñi, A. A new Spanish-language questionnaire for musical self-concept. Int. J. Music. Educ. 2017, 35, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Zabala, A.; Goñi, E.; Rodríguez-Fernandez, A.; Goñi, A. Un nuevo cuestionario en castellano con escalas de las dimensiones del autoconcepto. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2015, 32, 149–159. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=243045364005 (accessed on 16 September 2023).

| Contingency | Self-Efficacy | Success | Alternatives | Defense-lessness | Luck | Int. Locus | Ext. Locus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contingency | 1 | |||||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.678 ** | 1 | ||||||

| Success | 0.635 ** | 0.791 ** | 1 | |||||

| Alternatives | 0.711 ** | 0.769 ** | 0.719 ** | 1 | ||||

| Defenselessness | −0.013 | 0.053 | 0.040 | 0.106 ** | 1 | |||

| Luck | 0.059 | 0.080 * | 0.125 ** | 0.175 ** | 0.635 ** | 1 | ||

| Int. locus | 0.841 ** | 0.916 ** | 0.898 ** | 0.895 ** | 0.052 | 0.124 ** | 1 | |

| Ext. locus | 0.025 | 0.073 * | 0.091 ** | 0.155 ** | 0.907 ** | 0.901 ** | 0.097 ** | 1 |

| Parents | Teachers | Peers | Peers1 | Peers2 | Sum ‘Social Support’ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | 1 | |||||

| Teachers | 0.510 ** | 1 | ||||

| Peers | 0.672 ** | 0.437 ** | 1 | |||

| Peers1 | 0.682 ** | 0.430 ** | 0.961 ** | 1 | ||

| Peers2 | 0.522 ** | 0.362 ** | 0.871 ** | 0.701 ** | 1 | |

| Sum ‘social support’ | 0.903 ** | 0.721 ** | 0.863 ** | 0.849 ** | 0.716 ** | 1 |

| Correlations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrum. Compet. | Instrum. Incompet. | Social Mot./Personal Dev. | Emotional Factor | Sum Factor for the Scale | |

| Instrumental Competence | 1 | ||||

| Instrumental Incompetence | −0.269 ** | 1 | |||

| Social Mot./Personal Dev. | 0.633 ** | −0.069 * | 1 | ||

| Emotional factor | 0.516 ** | −0.081 * | 0.609 ** | 1 | |

| Sum factor for the scale | 0.858 ** | −0.541 ** | 0.788 ** | 0.685 ** | 1 |

| Correlations | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instr. Comp. | Instr. Incomp. | Social M & P. D | Emotional | Sum facT M.I SC | Contingency | Self-Efficacy | Success | Alternatives | Defenselessness | Luck | Internal Locus c. | External Locus of Control | Parents | Teachers | Peers | Peers1 | Peers2 | Sum Social Sup | |

| Instr. Co. | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Inst. Inc. | −0.269 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| SM and PD | 0.633 ** | −0.069 * | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Emotio | 0.516 ** | −0.081 * | 0.609 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Su MISC | 0.858 ** | −0.541 ** | 0.788 ** | 0.685 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Conting | 0.430 ** | −0.102 ** | 0.310 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.386 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Self-effic | 0.488 ** | −0.153 ** | 0.316 ** | 0.302 ** | 0.440 ** | 0.678 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Success | 0.415 ** | −0.107 ** | 0.293 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.376 ** | 0.635 ** | 0.791 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| Alternat. | 0.510 ** | −0.093 ** | 0.397 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.465 ** | 0.711 ** | 0.769 ** | 0.719 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Defensel. | 0.031 | 0.176 ** | 0.013 | −0.026 | −0.057 | −0.013 | 0.053 | 0.040 | 0.106 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| Luck | 0.084 ** | 0.216 ** | 0.113 ** | 0.058 | 0.005 | 0.059 | 0.080 * | 0.125 ** | 0.175 ** | 0.635 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| IL Contr | 0.517 ** | −0.129 ** | 0.368 ** | 0.328 ** | 0.467 ** | 0.841 ** | 0.916 ** | 0.898 ** | 0.895 ** | 0.052 | 0.124 ** | 1 | |||||||

| EL Contr | 0.063 * | 0.216 ** | 0.069 * | 0.017 | −0.029 | 0.025 | 0.073 * | 0.091 ** | 0.155 ** | 0.907 ** | 0.901 ** | 0.097 ** | 1 | ||||||

| Parents | 0.599 ** | −0.103 ** | 0.721 ** | 0.470 ** | 0.653 ** | 0.339 ** | 0.367 ** | 0.324 ** | 0.411 ** | −0.005 | 0.098 ** | 0.404 ** | 0.051 | 1 | |||||

| Teachers | 0.518 ** | −0.107 ** | 0.507 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.553 ** | 0.446 ** | 0.483 ** | 0.445 ** | 0.487 ** | −0.042 | 0.067 * | 0.523 ** | 0.013 | 0.510 ** | 1 | ||||

| Peers | 0.469 ** | −0.033 | 0.560 ** | 0.407 ** | 0.500 ** | 0.250 ** | 0.321 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.367 ** | 0.079 * | 0.173 ** | 0.342 ** | 0.138 ** | 0.672 ** | 0.437 ** | 1 | |||

| Peers1 | 0.467 ** | −.030 | 0.563 ** | 0.396 ** | 0.497 ** | 0.203 ** | 0.303 ** | 0.268 ** | 0.337 ** | 0.101 ** | 0.199 ** | 0.313 ** | 0.165 ** | 0.682 ** | 0.430 ** | 0.961 ** | 1 | ||

| Peers2 | 0.381 ** | −0.032 | 0.444 ** | 0.346 ** | 0.407 ** | 0.283 ** | 0.289 ** | 0.248 ** | 0.348 ** | 0.024 | 0.091 ** | 0.326 ** | 0.063 * | 0.522 ** | 0.362 ** | 0.871 ** | 0.701 ** | 1 | |

| So. Su. Su | 0.632 ** | −0.094 ** | 0.725 ** | 0.545 ** | 0.681 ** | 0.397 ** | 0.451 ** | 0.403 ** | 0.492 ** | 0.017 | 0.138 ** | 0.489 ** | 0.085 ** | 0.903 ** | 0.721 ** | 0.863 ** | 0.849 ** | 0.716 ** | 1 |

| Model | Standardized Coefficients | t. | Sig. | F. | Corrected R-Squared | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sex | 0.177 | 5.636 | 0.000 | 31.761 | 0.030 |

| 2 | Sex | 0.176 | 5.619 | 0.000 | 19.231 | 0.036 |

| Urban/rural | 0.080 | 2.554 | 0.011 | |||

| 3 | Sex | 0.135 | 4.904 | 0.000 | 120.034 | 0.267 |

| Urban/rural | 0.056 | 2.051 | 0.041 | |||

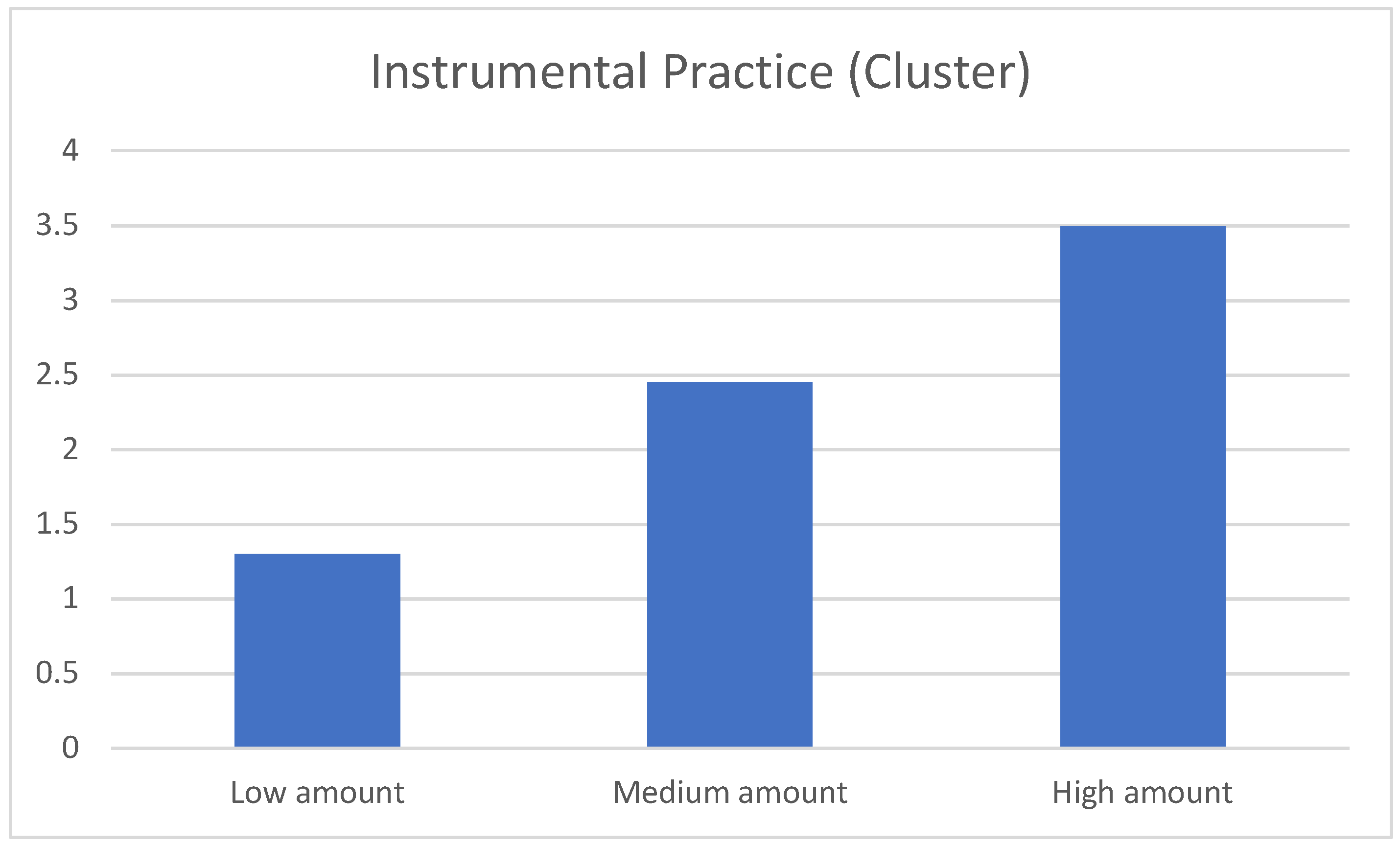

| Inst. practice cluster | 0.484 | 17.592 | 0.000 | |||

| 4 | Sex | 0.134 | 5.421 | 0.000 | 169.887 | 0.408 |

| Urban/rural | 0.032 | 1.294 | 0.196 | |||

| Inst. practice cluster | 0.411 | 16.355 | 0.000 | |||

| Internal locus | 0.384 | 15.285 | 0.000 | |||

| 5 | Sex | 0.072 | 3.232 | 0.001 | 226.536 | 0.535 |

| Urban/rural | 0.013 | 0.574 | 0.566 | |||

| Inst. practice cluster | 0.239 | 9.711 | 0.000 | |||

| Internal locus | 0.194 | 7.723 | 0.000 | |||

| Social support | 0.461 | 16.353 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zarza-Alzugaray, B.; Casanova, O.; Zarza-Alzugaray, F.J. Musical Instrumental Self-Concept, Social Support, and Grounded Optimism in Secondary School Students: Psycho-Pedagogical Implications for Music Education. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030286

Zarza-Alzugaray B, Casanova O, Zarza-Alzugaray FJ. Musical Instrumental Self-Concept, Social Support, and Grounded Optimism in Secondary School Students: Psycho-Pedagogical Implications for Music Education. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(3):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030286

Chicago/Turabian StyleZarza-Alzugaray, Begoña, Oscar Casanova, and Francisco Javier Zarza-Alzugaray. 2024. "Musical Instrumental Self-Concept, Social Support, and Grounded Optimism in Secondary School Students: Psycho-Pedagogical Implications for Music Education" Education Sciences 14, no. 3: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030286

APA StyleZarza-Alzugaray, B., Casanova, O., & Zarza-Alzugaray, F. J. (2024). Musical Instrumental Self-Concept, Social Support, and Grounded Optimism in Secondary School Students: Psycho-Pedagogical Implications for Music Education. Education Sciences, 14(3), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030286