1. Introduction

Black women with PhDs have shorter lifespans than white women

1 who dropped out of high school [

1]. While public health generally regards education as a significant determinant of health, this disparity brings into question the effectiveness of educational trajectories that aim for upward mobility but may not safeguard the health and well-being of those they intend to benefit.

The discrepancy in life outcomes related to the schooling of Black children underscores a broader equity issue. This is possibly attributed to the pronounced health disparities within BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) communities. These disparities are deeply intertwined with toxic stressors like racial discrimination, socioeconomic challenges, and premature death [

2,

3].

In our research [

4,

5,

6] the root of the health–equity issue in relation to schooling begins with the definition of education itself. Drawing from [

7] differentiation between schooling and education, we aim to shed light on the often-incompatible relationship between formal schooling and Black wellness. Schooling, in many ways, continues the legacy of colonization and subjugation, designed to maintain the existing order [

8,

9]. It often functions to disregard and ultimately disconnect Black children from their indigenous languages, histories, and medicines [

10,

11] On the contrary, education, as defined by Shujaa [

7], emphasizes the transmission of values, aesthetics, and spiritual beliefs, sustaining a culture’s essence. Unlike the American schooling system, which may inadvertently set Black youth on a path of self-marginalization, education fosters cultural vitality.

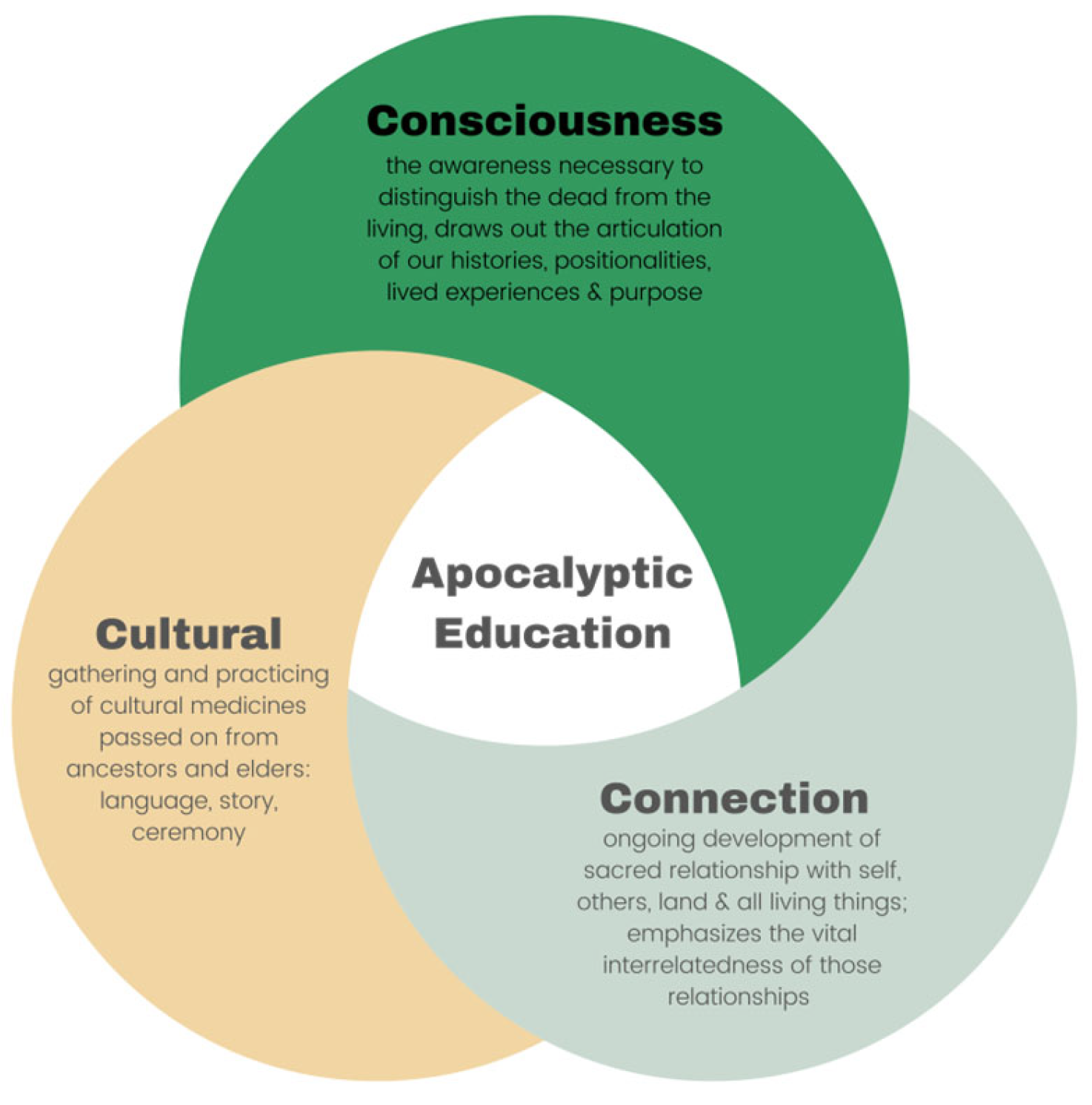

Our Apocalyptic Educational framework [

4] challenges the current perception of schooling as the sole path to wellness and sustainability for Black people (See

Figure 1). Instead, it emphasizes three pillars rooted in Black indigenous traditions: culture, community, and consciousness. Culture is particularly highlighted as a vital force, carrying with it ancestral teachings, stories, and rituals that, in turn, nurture community and consciousness.

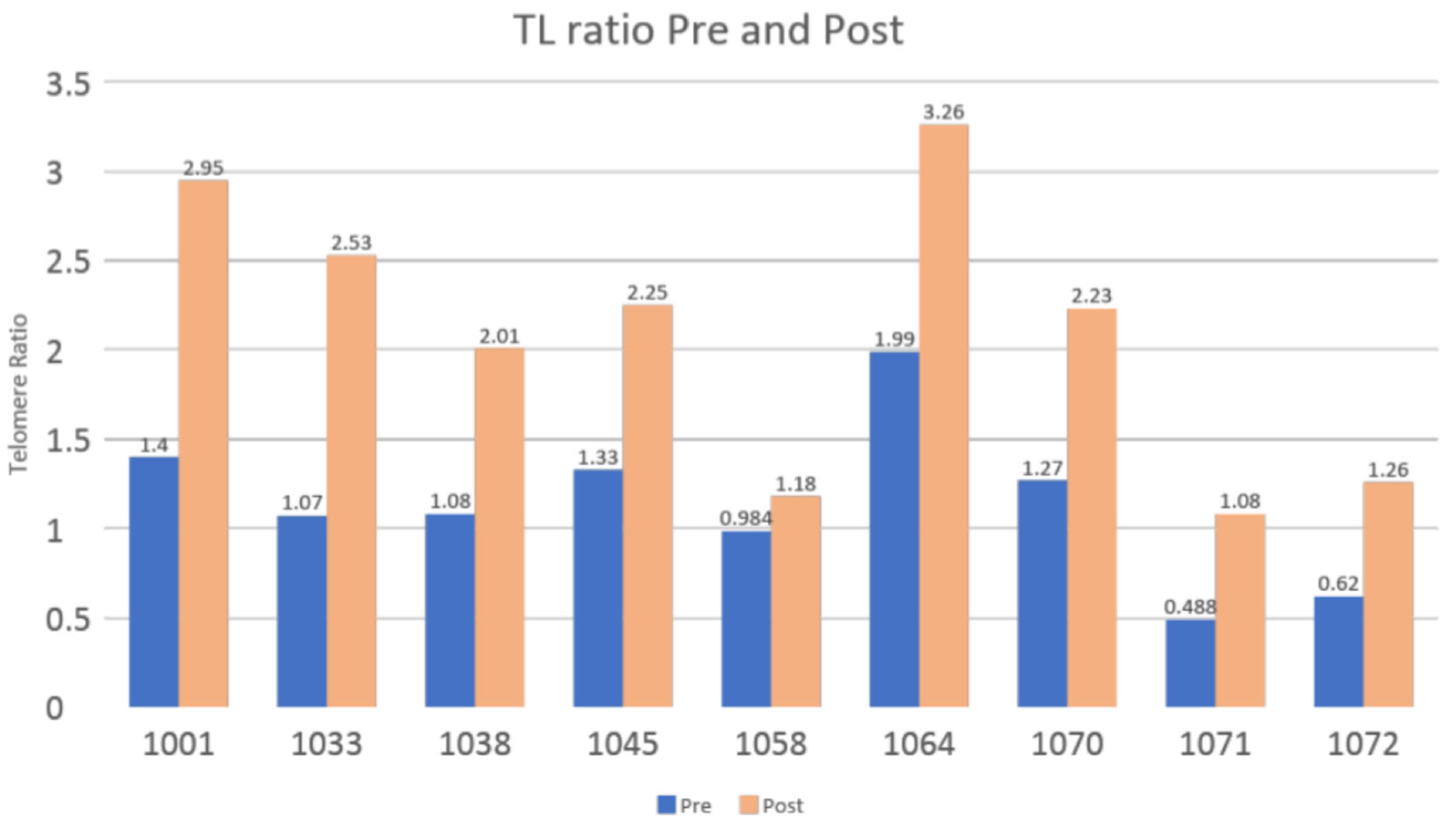

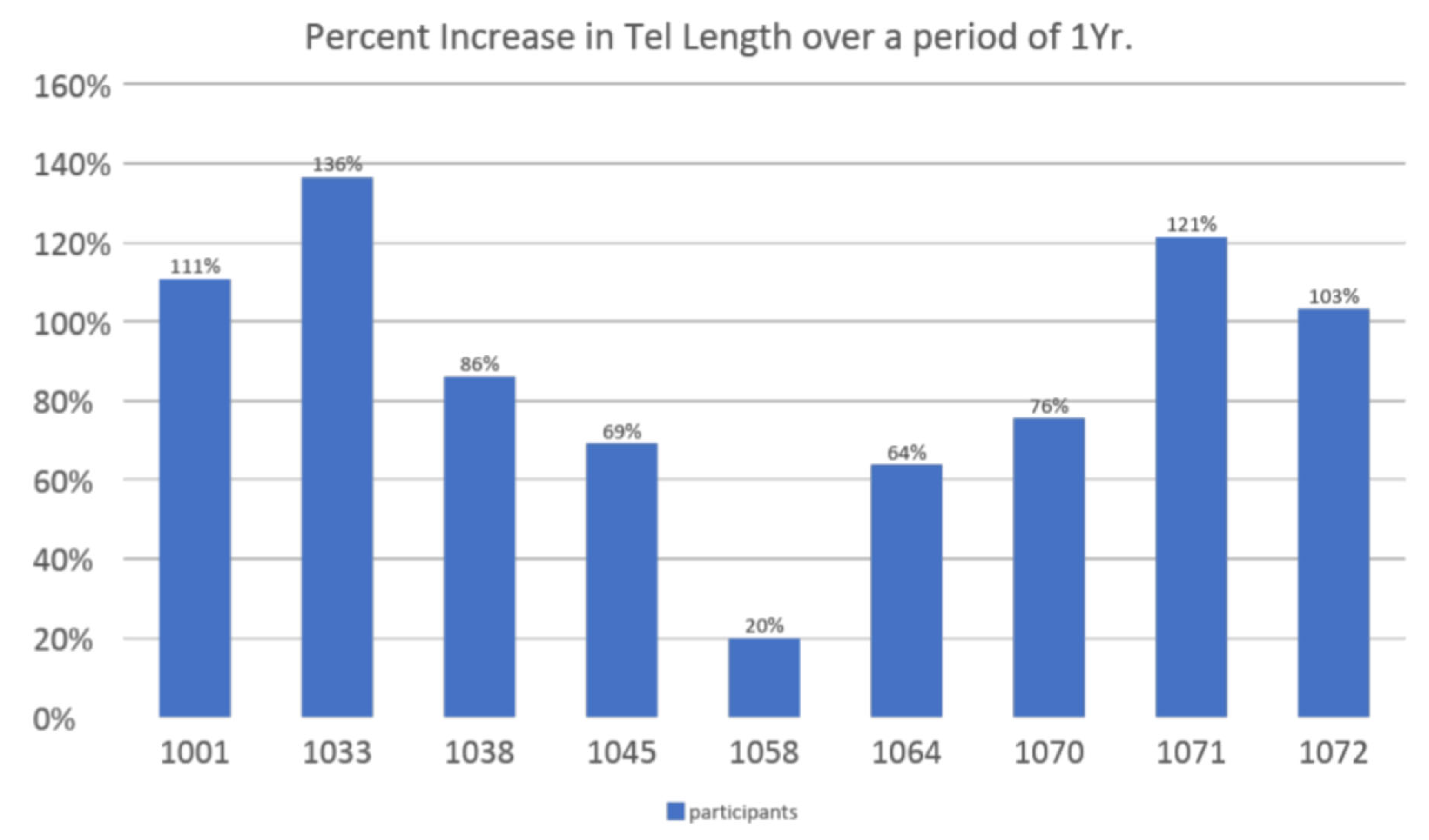

Our recent research has drawn connections between culturally responsive pedagogy and improved health indicators in BIPOC youth. Over a four-year period, we observed correlations between our intervention and health markers like cortisol, oxytocin, and telomere lengths [

5] (See

Figure A1 and

Figure A2). Beyond these biological indicators, the youth also reported an enriched sense of community and a heightened consciousness, allowing them to discern, articulate, and embrace their histories and identities.

Building on this understanding, our Apocalyptic Education framework views conventional schooling as misaligned with the holistic well-being of Black children. Our approach has culminated in the development of a health-centered metric: a validated youth wellness scale. This tool aids educators in transitioning from mere schooling to education, positively influencing health outcomes. Through our research, we have come to understand that traditional schooling alone does not equate to wellness. Rather, culture and its subsequent impact on community and consciousness are essential wellness indicators. This article delves into the development of our wellness scale and concludes with its components, demonstrating our equity-driven approach to fostering improved health outcomes for Black youth.

This paper seeks to clarify the integration of the Apocalyptic Education (AE) framework with the creation of a culturally relevant wellness scale, informed by our longitudinal study examining the effects of culturally relevant teaching on BIPOC youth health outcomes. Our upcoming literature review situates the necessity of this inquiry amidst the larger conversation on educational disparities, while the theoretical framework section positions AE as the foundation for our intervention. The core of this paper details the construction and validation of the wellness scale, emphasizing its role in evaluating the well-being of Black and Indigenous youth in educational environments.

Our primary aim is to unveil the wellness scale, exploring the impact of culturally relevant pedagogy, as conceptualized through AE, on the health and well-being of BIPOC students. The research questions are designed to investigate the potential of AE-informed practices to be measured via the wellness scale, thereby offering new insights into the beneficial effects of culturally responsive education on student health.

Research Questions:

How can the principles of Apocalyptic Education (AE) be operationalized to develop a culturally relevant wellness scale for BIPOC youth?

What is the validity and reliability of the developed wellness scale for measuring the well-being of Black and other Indigenous youth within educational settings?

How does engagement with culturally relevant pedagogy, informed by AE, impact the health outcomes of BIPOC students as measured by the wellness scale?

To what extent does the wellness scale capture the nuanced effects of cultural and community connectedness on the overall well-being of BIPOC students?

2. Literature Review

Education has long been championed as a ladder to improved health and socioeconomic status [

12,

13,

14] Yet, paradoxes in health outcomes challenge this narrative, especially among marginalized communities [

1]. This literature review examines the intersection of cultural identity and wellness within the schooling trajectories of Black and other Indigenous youth [

15]. It dissects the extant body of research to explore how culture serves not only as a linchpin in the quest for equity but also as a crucial determinant of well-being, shedding light on the limitations of conventional schooling systems that often fail to cater to the holistic needs of BIPOC youth and communities.

The selected studies provide insight into the protective role of ethnic identity against adverse mental health outcomes, the significance of cultural embeddedness for well-being, and the profound impacts of discrimination. They also discuss the potential of cultural revitalization and resilience-building through educational practices that honor and integrate cultural practice. Furthermore, this review critiques and contextualizes scales and metrics developed to measure wellness, emphasizing their role in shaping educational policies and practices that aim to foster equity. Through this exploration, the review supports a paradigm shift towards an Apocalyptic Education framework, advocating for education systems that empower Black youth through culture, community, and consciousness.

2.1. Impact of Discrimination and Racism on Mental Health

The literature on the impact of discrimination and racism on health, particularly in minoritized communities, presents a complex picture of how such experiences shape psychological well-being. Motley et al. [

16] have made significant contributions to this field with the Modified Classes of Racism Frequency of Racial Experiences Measure (M-CRFRE), which is a tool designed to assess exposure to perceived racism-based police violence among Black emerging adults. Their methodological rigor, involving focus groups and cognitive interviews with Black emerging adults, content expert panels, and pilot surveys, led to the identification of 16 new survey items. The resulting measure not only demonstrates construct validity and internal reliability but also bridges a critical gap in quantifying such exposures and their impact on mental health.

Saleem et al. [

17] have further expanded the discourse by examining how ethnic–racial socialization (ERS) interacts with experiences of discrimination. Their study, involving a significant cohort of US Black and Caribbean Black adolescents, reveals that while ERS serves as a critical tool in managing the impact of racial discrimination, it does not uniformly shield against the psychological repercussions. In fact, for Caribbean Black youth, high levels of preparation for bias were linked to increased stress and reduced mastery beliefs, suggesting a nuanced and possibly counterintuitive interplay between ERS and discrimination.

The prevalence of perceived discrimination among Black and Caribbean Black youth is highlighted in a study by Seaton et al. [

18], which draws from a nationally representative sample and underscores how common discriminatory incidents are for Black youth. The association between perceived discrimination and various aspects of psychological well-being—depressive symptoms, self-esteem, life satisfaction—emphasizes the insidious impact of discrimination across different stages of development and genders.

Lastly, Cokley [

19] provides a conceptual framework to understand Black identity by discussing the challenges in defining racial(ized) identity and ethnic identity as well as Africentric values. This work prompts a reevaluation of how identity is measured and conceptualized, which is crucial for understanding how discrimination and racism are internalized and resisted by individuals.

In synthesizing these studies, it becomes evident that discrimination and racism exert a profound influence on mental health, with various factors modulating this effect. The M-CRFRE’s development is a step forward in measuring and understanding these experiences. However, the impact of discrimination is complex, as shown by Saleem et al. [

17], with ERS having variable effects on stress and coping mechanisms among Black adolescents. Seaton et al.’s [

18] findings on the prevalence of discrimination underscore its widespread nature and its correlation with negative mental health outcomes. Cokley’s [

19] exploration of identity challenges underscores the need for nuanced approaches to understanding the psychological impact of racism. This body of research calls for culturally tailored interventions and a deeper examination of the heterogeneity within Black communities regarding the experiences and effects of racism and discrimination.

2.2. Educational Trajectories for Equity and Wellness

Educational trajectories are deeply intertwined with the well-being of students. Research by Davis et al. [

20] delves into the long-term impacts of bullying victimization on adolescents, tracing a path that links such experiences to depression, decreased academic achievement, and problematic drinking behaviors. Their study underscores the pivotal role educational environments play in either worsening or alleviating health challenges. By employing an auto-regressive latent trajectory model, Davis and colleagues [

20] were able to scrutinize the within-person associations between these variables, providing evidence for the interpersonal risk model. This model posits that bullying victimization can initiate a domino effect of challenges, with academic achievement being a crucial link between early victimization and later problematic behaviors, such as drinking. Their findings emphasize the necessity for early interventions that address bullying, academic support, and the prevention of substance abuse.

In the pursuit of understanding well-being in the context of educational settings, Fry et al. [

21] contribute by examining the influence of a perceived caring climate on emotional regulation and psychological wellness among youth sports participants. Their structural equation modeling highlights the mediational role of affective self-regulatory efficacy, suggesting that a nurturing environment can significantly enhance well-being through improved emotional regulation. The implications of this study extend beyond the sports arena, suggesting that fostering a supportive and caring atmosphere in educational institutions can have a profound impact on the emotional and psychological health of students.

The importance of hope in the educational journey, especially among minoritized adolescents, is illuminated by the work of Roesch et al. [

22]. Their daily diary assessment of dispositional hope demonstrates that the component of pathways, which pertains to an individual’s perceived ability to generate routes to achieve goals, is positively related to the use of adaptive coping strategies. Hope not only acts as a buffer against stress but also promotes a variety of positive coping mechanisms such as problem-solving, planning, and positive thinking. This suggests that educational frameworks that cultivate hope and provide resources for its development can empower students to navigate adversity and enhance their overall well-being.

In sum, these studies collectively argue for educational environments that prioritize the psychological well-being of students through multi-faceted approaches. Integrating bullying prevention programs, creating caring and supportive climates, and nurturing dispositional hope are all strategies that can contribute to healthier educational trajectories. Such environments can mitigate the negative consequences of bullying victimization, improve emotional regulation, and equip students, particularly those from marginalized backgrounds, with the coping strategies necessary for resilience. This comprehensive approach to education underscores the need for policies and practices that recognize the holistic nature of student well-being and the critical role educational settings play in shaping life outcomes.

2.3. Racial Cultural Identity and Well-Being

The interplay between cultural identity and mental health is a pivotal area of study, demonstrating the protective influence of ethnic identity amidst various psychological stressors. Fetter and Thompson [

23] shed light on the distress Native American college students experience due to historical loss. Their findings are important in illustrating how a strong ethnic identity can serve as a buffer, lessening the detrimental impact on well-being. This concept of cultural resilience is a recurring theme in the literature, with Neblett et al. [

24] pinpointing racial identity as a mediating factor that potentially shields Black youth from depressive symptoms. Their research suggests that positive racial socialization messages and activities enhance feelings of positivity towards one’s racial group, which, in turn, can mitigate depressive symptoms.

Kim et al. [

25] provide further evidence for the importance of cultural and identity-based frameworks in mental health. They explored how self-esteem and a future-oriented perspective mediate the relationship between family stress and mental health problems among Black youth. Their work posits that fostering future orientation and self-esteem could be vital in developing resilience against the adverse effects of stress.

The significance of cultural embeddedness is affirmed by the Maori Cultural Embeddedness Scale (MaCES) introduced by Fox et al. [

26]. The scale’s structural validity in assessing the depth of an individual’s cultural integration underlines the positive correlation between cultural connectedness and health outcomes. The MaCES provides a nuanced understanding of how being deeply rooted in one’s culture can influence well-being.

Shea et al. [

27] take the theoretical understanding of cultural identity’s impact on mental health into practical application within the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. Their decade-long study of cultural education and revitalization efforts underscores the healing power of reclaiming cultural identity and language. The results reveal significant positive outcomes, such as increased educational attainment, language usage, and engagement in tribal events, reflecting a broader conception of wellness that extends beyond individual health to encompass community and cultural vitality.

In essence, these studies collectively argue for the acknowledgment of cultural identity as a crucial factor in promoting mental health and well-being. They highlight the need for interventions and systemic changes that not only recognize but actively reinforce the cultural strengths of minority communities. The protective role of ethnic identity and the benefits of cultural revitalization suggest a path towards healing racial and cultural traumas, ultimately contributing to a holistic sense of wellness that is culturally informed and sustained.

2.4. Synthesis and Conclusion

This literature review reveals a consistent theme: cultural identity and engagement are critical to the well-being of minoritized youth. The studies collectively underscore the necessity of culturally responsive pedagogies and interventions that validate and strengthen ethnic identity, offer protection against the detrimental effects of discrimination, and foster resilience through cultural revitalization and supportive educational environments. This body of work seems to support our Apocalyptic Education framework, which emphasizes culture and its impact on community and consciousness. Moreover, the research underscores the importance of developing robust metrics, such as the youth wellness scale, to capture the multi-dimensional nature of wellness in culturally diverse populations. The reviewed studies demonstrate an equity-driven approach to fostering improved health outcomes for Black youth, challenging the current perception of schooling as the sole path to prosperity and emphasizing the need for a holistic integration of culture into educational frameworks.

By weaving together findings from the provided studies, the literature review substantiates our understanding that education (grounded in cultural wellness practices) must be centered if we truly value the health and well-being of Black and other Indigenous youth.

2.5. Addressing Gaps in Research for Holistic Wellness Metrics

The research landscape on cultural identity and wellness, while rich, reveals gaps in addressing the full cultural spectrum influencing youth health outcomes. Current scales lack a deep engagement with ancestral knowledge, connections to the natural world, and the profound impact of communal interdependence. Ancestral traditions, environmental ties, and meaningful community relationships are crucial yet underrepresented in wellness metrics.

Existing studies acknowledge the role of cultural involvement and identity but often overlook the intrinsic value of traditional ecological knowledge and the healing power of interconnection that are central to many Indigenous and ancestral cultures. Moreover, while community support is recognized, the significance of a deeply interconnected community, where relationships go beyond support to shared experiences and collective identity, is not fully captured.

Future research must strive to develop culturally encompassing metrics that value ancestral wisdom, ecological connections, and deep community bonds to truly reflect and enhance the wellness of BIPOC youth. To be clear, these metrics are not aimed at improving schooling outcomes but rather are essential for guiding effective, culturally congruent interventions and educational strategies that promote well-being and just that.

3. Theoretical Framework

When viewed from a western epistemological framework, the scales we describe in the previous section could be assessed as radical and even threatening to modernity, given their purported capacity to affirm identities and cultures that exist outside of rigid intellectual enclosures [

28]. Although we might normally celebrate the idea that the scales represent a type of epistemological insurgency, our engagement with Apocalyptic Education (AE)—as a theoretical framework—also leads us to a different interpretation of the efficacy of these tools.

We see “theoretical frameworks” as constructed environments or dwellings in which scholars hold critical conversations. Taking this analogy further, each house (theoretical framework) has a foundation. This foundation is made up of theories or various lenses used to view and interpret social life [

29] The different theories that undergird different theoretical frameworks generate disparate questions, conversations, and conclusions.

As a framework, AE sits upon a braided foundation of kindred Black radical and other Indigenous traditions of thought (theories) such as the Dagara Medicine Wheel [

10], Ki Kongo Cosmograms [

30], Indigenous Ecologies [

31,

32,

33,

34], Black Feminist Epistemologies [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], Afro-pessimism [

40,

41,

42] Critical Race Theory’s Racial Permanence [

43] and other anti-colonial, abolitionist, and fugitive groundings in education [

7,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. From this foundation, AE describes a life-alignment praxis rooted in two intertwined, mutually reinforcing re-memberings [

35].

3.1. Rooted Memories

The first rooted memory of AE is that the end of the western world grants more opportunities for Black and other Indigenous peoples’ wellness. Although the dominant media often portrays the “apocalypse” in a horrific light, we re-member that the current world of modernity came into being specifically on top of millions of unmarked, desecrated graves representing countless apocalypses of African and other Indigenous worlds. Thus, we pronounce schooling (and our hopes there within) as dead, specifically because western schools have always been extended apparatuses of the plantation. They are imperial warcraft technology formulated to legitimize and sustain the ongoing apocalypses against our people by way of epistemicide. Because there has yet to be a holistic abolition, part and parcel, of the systems of truth and logic that first animated these institutions, they continue to operate according to their original mandate. This rooted memory necessitates that we examine products that reinforce schooling (such as scales) with a critical eye.

The second root of AE recalls and urges the transmission of African cultural ways of being that conspire on behalf of our survival and autonomy [

51], aimed at quickening our movement to spaces that are uninhabitable by those who mean us harm [

4,

5,

15]. AE invokes the rituals that help us bring back life within this holistic understanding of ourselves in relation to our communities. This second root gives direction to our critiques by prompting an interrogation of schools and the elements that reinforce them (such as scales) by assessing how they do or do not align with ancestral groundings and culture.

3.2. A Response Typology

We have found that the recollection of these two rooted knowings often informs a kind of response trajectory for young people in refusal [

52,

53,

54,

55], unschooling families [

56], grounded elders, mournful educators [

57], fugitive researchers [

58], and other “friends of truth” [

50] engaged in both conscious and subversive efforts to abolish the plantation technology known as schools [

48]. For example, rather than attempting to resuscitate and reform the US system of education, Black and other Indigenous abolitionists who are conscious that schools are dead (and deadening) seek instead to

overgrow their decaying violence through the cultivation of loving educational sanctuaries on the metaphorical outskirts of the settler colonial plantation. We expand on these types of responses below in order to provide further basis for our development of a scale that holistically weaves together elements that more accurately assess the wellness of Black and other Indigenous youth.

3.3. Consciousness (Moss)

“Flight” is one response to schooling revealed through our Apocalyptic Education framework. Although magical human flight is prevalent throughout the storying traditions of many peoples indigenous to the African continent, diasporic versions of these tales have often been interpreted as tragic metaphors for the documented practice of intentional un-aliving amongst enslaved communities [

59]. Igbo’s Landing, the site of one of the first reported cases of mass suicide in the US, serves as a well-known exemplar of this practice. In 1803, a group of 75 Igbo people, having overtaken their captors on the

York, a coastal slave vessel, ran the ship aground in Dunbar Creek on St. Simons Island in Glynn County Georgia. The group of Africans was then led on a march by one of their high priests back into the water, collectively choosing to drown rather than navigate the treacherous terrain littered with slave catchers and plantations. However, there is an argument that the Igbo people were actually engaged in a transformational ceremony in order to fly home

over the ongoing violence of slavery [

60]

AE analogizes this practice of flying over the plantation with the practice of distinguishing the possibilities of education outside of school (i.e., flying) from the conforming propositions offered by schools (i.e., the plantation). Such consciousness is important because the society we inhabit has inverted these concepts. The logic of western schooling places unmitigated value on degree attainment, capitalism, and the petty trinkets and fiefs associated with higher positions in the hierarchy, which often do not lead to the fulfillment they promise [

4]. In fact, schooling derides Black and other Indigenous forms of education that are founded on the understanding that every person is an inherent blessing imbued with the gifts of cultural medicine. Unlike schooling, this type of education supports a variety of initiations and other rites of passage ceremonies to remember, activate, and complete our interconnected sacred purpose for the benefit of past, present, and future life-making and knowledge [

61].

AE supports this consciousness-raising, particularly in Black and other Indigenous children, parents, caretakers, educators, and researchers. For many of us, it may feel apocalyptic to accept that schools and schooling are dead in relation to our people’s well-being and liberation. Once we have come to this realization, the question that naturally follows is, if not by schools, how else might we proceed? We uplift a similar problem-posing and consciousness that may have been present amongst the Igbos in Dunbar Creek. “If not onto the plantation and other prospects of eventual bondage, how else might we proceed?” We liken this consciousness to moss, our plant relative, that often appears “dead” in particularly toxic environments and also has the skill to overgrow and flourish on top of presumably dead things. We envision a life that comes after death over the trappings of schooling.

When applied to the development of new tools (scales) to help measure Black and Indigenous youth wellness, AE supports the inclusion of items that assess their access to memories that distinguish the death of schooling from the life offered through education.

3.4. Cultural (Knapsack)

The AE-informed response to schooling that follows moss/consciousness is the knowledge that another life exists (and is always already being lived)

around the school, just as another life was possible outside of the plantation. This teaching is best exemplified by the everyday practices of maroon communities [

62] Maroons were (are) fugitive individuals who successfully fled (flee) enslavement and the state by way of cultivating autonomous communities outside of the strongholds of the plantation [

63,

64]. Maroons did not negotiate with the slave master or wait for the plantation to be perfectly just. They retained no faith that the system of slavery would evolve into something satisfactory or reformable. Instead, the maroon understood that their autonomy and the plantation were irreconcilable. They chose to move away from both the plantation and the entire system of the state it was founded within.

With this logic applied to schools and schooling, AE offers tools for seeking to occupy and live within the pockets, crevices, and outskirts of autonomy that are sustained around schools, colleges, and universities. Existing in the surroundings of the plantation becomes more viable when we have access to the cultural knapsacks full of braided hair, rituals, food, sacred connections to the land, metaphorical stories, photographs, astronomy, and other essential items left by enslaved Africans to their families and children who were sold (or who ran) away from the plantation [

4]. They constructed these cultural kits in order to expand the possibilities of the survival and autonomy of their kin. They were also intended to spark the memory that the ability to survive in the surround comes from the practice of our ancestral ways of being. That is our connection to the knapsack, to the ongoing offering of love that our ancestors have left us.

The practice of marronage and the sharing of cultural knapsacks following the enactment of moss/consciousness help inform new cultural and communal wellness scales in a couple of ways. They remind us to assess the extent to which young people feel supported in abandoning the violent impositions of schooling, accessing unconditional love, and being prepared to join more autonomous and liberated territories of learning and life-making.

3.5. Communal (Okra)

As the final dimension of this AE response typology, we uplift the crucial component of community—the resilient container of Black and other Indigenous peoples’ continuity. We derive important knowledge of this element from the specific circumstances regarding the journey of okra seeds from the dungeons of West Africa to plantations on Turtle Island and other locations where Black people endured enslavement. Bearing witness and unspeakable pain during the ending of their worlds, African people partnered with Okra and braided the plant’s seeds into their hair throughout the middle passage. This act was not merely a means of preserving an essential crop but symbolized the transfer of communal vitality.

The lesson of okra extends to the concept of communal networks as vital lifelines in sustaining Black and other Indigenous youth wellness, particularly in the face of the ongoing decay of the present world. These networks act as safe, nurturing spaces where interdependent culture is sustained and evolved towards expanding collective autonomy and survival. Thus, in the spirit of our ancestors who braided seeds of hope and survival into their hair, we weave together our communal bonds, ensuring that we not only endure but thrive in the face of new challenges and worlds to come. This third type of AE response suggests that Black and other Indigenous youth wellness is sustained through unconditionally loving relationships. Sans these, it is untenable to conceive of life anew beyond the end of the world. Thus, a more holistic assessment of youth wellness should feature an evaluation of the extent of young people’s access to right relations within robust communities.

Overall, we explore the Apocalyptic Education framework as a response to the historical and systemic marginalization experienced by BIPOC students within American educational systems. AE serves as both the motivation and theoretical foundation for our intervention study, which seeks to identify and validate measures of wellness rooted in cultural relevance and community connectedness.

4. Methodology

Our research adopts a mixed-methods approach, combining biomarkers of health from the implementation of AE in educational settings with a quantitative validation of the wellness scale through psychometric analysis. This methodology is grounded in a culturally responsive research paradigm that emphasizes the centrality of communal connections, culture, and consciousness in educational research. Furthermore, we delve into issues of positionality to reflect on how our identities and experiences as researchers influence the interpretation of our findings, while also ensuring that our methodological choices align with the participatory and emancipatory goals of Apocalyptic Education.

Methodology explains and justifies the techniques and tools by which we proceed with research [

65]. In the following section, we aim to explain how we arrived at the decision to put forward the proposed scales, particularly in light of the apparent contradictions regarding AE and utilizing scales. When we employ the framework of AE, we understand that although the scales we discussed in the literature review present helpful frames for understanding the impact of cultural experiences on mental health, they do not holistically consider or measure

integrated elements of wellness (i.e., mind, body, spirit, ancestral, familial, community/village, society, ecology, future) as mutually constitutive, reinforcing dimensions of identity. The previously mentioned roots of AE rationalize this dearth of holistic scales as characteristic of the anti-black epistemology and world that we inhabit. There was an attempt to unbraid African people’s integrated indigeneity in slave dungeons [

66]; sever our people’s ancestral knowings and ways of being at attenuation wells beyond and through the fabled portal “Door of No Return” [

67] season away any remnant of sustenance practice, familial ties, rites of passage, and land-based knowledges on plantations [

68,

69] and continuously overwrite collective Indigenous epistemologies with bifurcated Cartesian modes of intellectual thought. In turn, our survival is predicated on the understanding that schooling is inextricably tied to this tortuous history and remains antagonistic to the health and wellness of our people.

While AE helps contextualize the gaps within the previously reviewed scales, it also reveals a pathway to healing/re-braiding the unnatural split between mental, physical, and spiritual elements of identity and wellness. Essentially, AE advocates for a somber urgency to bury the systems of knowledge, beliefs, and practices that rationalize the sorting, rewarding, and punishment of young people based on their adherence to schooling. Moreover, this compromised promise that greater advancement within schools will lead to gainful employment, financial security, food, shelter, and holistic wellness should be replaced with the increased growth of young people’s consciousness, culture, and communal connection. With this in mind, our arrival at the scales proposed herein hinges on what we call survival pending recovery.

Survival Pending Recovery

We recognize that it may seem inherently contradictory to employ AE in order to both criticize the existence of scales while also simultaneously informing a new set of scales. On the one hand, Black people have always assembled incongruent ways of knowing in order to inspire, practice, and enact something that is, as of yet, unknowable: our liberation [

70]. Thinking specifically about our approach, in previous publications, Tiffani and Kenjus conceptualized AE through the conceit of performing the roles of celebrants at a funeral for schools [

4] and the roles of facilitators of a support group for grieving survivors of schooling’s violences [

5]. Presently, we (Kenjus and Tiffani) argue that this paper, the tool we will soon discuss herein, and the way we are presenting this work primarily exist due to our actual status as “recovering academics.” Although we do not endorse recovery concepts originating from the philosophy of Alcoholics Anonymous for a variety of reasons, we think this framing can be helpful for contextualizing the more discordant notes and transitions present within this article and other aspects of our work.

To better demonstrate why we have come to understand ourselves as recovering academics, we invoke the current crisis impacting the Jarawa people. The Jarawa are a group of Afro-Asian hunter-gatherers who are indigenous to the Andaman Islands, a territory claimed by the Indian government. According to conservative estimates, they have resided in the island’s rainforests for over 50,000 years. Like other non-state persons, virtually everything about the Jarawa’s ways of living, their cultural and social organizations, their ideologies, the rugged terrain of their chosen home, and even their exclusive employment of an oral, non-written language, can all be read as strategic choices designed to keep the state at arm’s length [

71] They have willingly used arrows and words to communicate an unwavering intention to remain isolated from modernity:

[Outsiders] try to scare us.

—Yade

They kill all our pigs. Sometimes they give us some money or clothes. That’s how they steal our game. We used to only eat pigs, but since there are hardly any, we were forced to kill the deer to eat.

—Uta

They give us tobacco and teach us how to chew. And it’s not good for us. They give us alcohol and we don’t like it either. But they try anyway, to make us drink. We don’t like it. It’s bad. But they still try to influence us. That’s the other world…We don’t like the outside world. We don’t want to have any interaction or be too close to your world. We want to remain as we are.

In addition to poaching animals central to the Jarawa food systems, Indian settlers have also sexually assaulted members of the tribe, exposed the community to harmful diseases, and eviscerated huge swaths of their rainforest. Such deadly encroachments of the outside world have accumulated to threaten the very existence of the Jarawa. Apay suggests that this unfolding apocalypse against his people is being animated, in part, by their non-consensual subjection and coerced addiction to the mundane features of modernity (western technology, hunting habits, clothing, episteme, and illicit substances).

We grieve the horrors being endured by the Jarawa as well as the likely reality that their experiences will continue to echo across time in the minds, bodies, spirits, and postures of future generations. We (Tiffani and Kenjus) feel kindred ripples within our own corporeal selves as descendants of kidnapped Africans. In fact, according to some members of the Dagara people in Burkina Faso, our very exposure and compulsion to read, converse, and, ironically (also depressingly) to author research articles using colonial languages is understood to be a terminal disease:

Actually [the villagers] called this [western literacy] a terminal knowledge…Indeed I can’t forget how to read and write [in English] anymore. No matter how hard I try to do that…And I came to understand…that certain types of knowing deletes the opportunity of accessing other areas of knowledge [

73]

From this vantage point, we understand that even our most well-intended, radically written contributions, including the scale we present later in this article, might also demonstrate that our journey of recovering from schooling will be an ongoing one. Even when we have made a commitment to be clean, this concept of releasing all investments in addiction is never linear. In fact, one particularly relevant dynamic associated with coercive addiction is that healing requires the metabolization or intentional processing of the unhealthy components of said relationship. As Frantz Fanon [

74] observed, “Imperialism leaves behind germs of rot which we must clinically detect and remove from not only our lands but from our minds as well” (p. 46). Our prayer is that our children and our children’s children might not necessarily inherit this kind of relationship with this reality. However, we understand that this challenge deserves our honest attention and engagement.

This methodology is our acknowledgment of this dynamic and a necessary step in admitting that we (still) have a problem. In articulating AE, we have been attempting to declare that we have been harmed by our relationship with schooling in all of its iterations. We no longer want to engage or be close to this world. However, agreeing to a process of getting clean does not mean that we

are clean. Additionally, most attempts to go “cold turkey” and simply drop the connection to a toxic substance after prolonged, non-consensual exposure have been shown to both cause harm (due to the body’s adapted dependency) and lack sustainability [

75] Thus, the following sections on methods and the development of the scales can be viewed as our attempt to provide resources for a weaning process for individuals interested in undoing their corrosive and coercive relationships with schooling.

5. Methods

5.1. Participants and Procedure

This study’s sample consisted of 533 adolescents aged 14–19 (Mage = 16.25, SD = 1.22) from various high schools across a Western state. The sample identified as 39.2% male, 51.0% female, and 9.8% other/declined to answer. The racial/ethnic breakdown of the sample was self-reported as 54.0% Hispanic American/Mexican, 14.3% Asian American/Pacific Islander, 11.8% European American/White, 6.8% African American/Black, 12.9% Multi-ethnic/Other, and 0.2% declined to answer/did not respond. The current data were collected as a part of a four-year longitudinal investigation into how culturally relevant interventions impact the health outcomes of Black and other Indigenous youth. The referenced culturally relevant intervention consisted of (a) exposing adolescents to consciousness-raising experiences and discussions, (b) giving adolescents a comprehensive view of their cultures (e.g., encouraging them to embrace their culture’s Indigenous ways of being as well as teaching them about the histories of resilience), and (c) emphasizing the importance of cultural and community connection (e.g., teaching them rites of passage ceremonies, annual cultural celebrations, how intergenerational education models are imperative cultural tools, and how to thrive in adverse conditions). Data for the project consisted of interviews with the adolescents, analyses of existing student work, surveys that focused on psychosocial constructs (e.g., ethnic identity), and biomarkers of health (e.g., telomere measurements).

The data for the current study were collected via Qualtrics. A link to the survey was distributed via email to a group of high school educators who agreed to partner with the first author on this project. These educators distributed the surveys in their classrooms (when applicable) and/or forwarded the email to their respective networks of high school educators to distribute in the latter’s classrooms. All educators that were forwarded the link were educators in the same Western state. Students took the survey during school hours within an academic classroom. Participation in the current research was strictly voluntary and students could opt out at any time. Students who elected to take the survey spent, on average, about 20 min to complete it. Teachers were available to answer questions if students had any while completing the survey.

5.2. Measures

5.2.1. The Cultural Connectedness Scale and the Community Connectedness Scale

Items for the Cultural Connectedness and Community Connectedness scales were developed via an iterative process. The scales were developed as a result of the culturally relevant intervention mentioned above. Students, teachers, and program personnel wanted a measure that captured the constructs that they felt were major contributors to the students’ improved health outcomes (i.e., cultural and community connectedness) and could not find an existing measure that they thought captured the constructs in a culturally relevant way. As a result, the process of developing the current set of measures began. The first draft of the Cultural Connectedness scale consisted of 16 items, while the first draft of the Community Connectedness scale consisted of 17 items. These 33 items were developed based on all of the data from the intervention research, including interviews, surveys, observations, and biomarker data. After a first draft of items was created, the items underwent an expert review, where a scale development consultant reviewed the items. After this review, the Cultural Connectedness scale remained unchanged while the Community Connectedness scale was reduced to 15 items (two items were discarded due to being overly vague and potentially confusing to respondents). The response options for both scales were a Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree), with higher scores being indicative of higher amounts of perceived connectedness to one’s culture and/or community. The vision for both scales was that they should be easily and quickly completed given the time, resource, and logistical constraints of schools and community organizations (i.e., the environments where community intervention research typically takes place). Thus, it was decided that the final version of each scale would ideally consist of about 10 items so that they could quickly be administered alongside various other measures within a school or community organization without imposing too much of a time, resource, or logistical burden.

5.2.2. Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure

The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) is a 12-item scale that measures ethnic identity [

76]. It consists of two subscales: exploration and commitment [

77]. The exploration subscale measures the extent to which one has explored their ethnic identity, while the commitment subscale measures one’s sense of affiliation to their ethnic identity. The exploration subscale consists of five items (e.g., “I have spent time trying to find out more about my ethnic group, such as its history, traditions, and customs”) and the commitment subscale consists of seven items (e.g., “I have a clear sense of my ethnic background and what it means for me”). Response options for both subscales were on a Likert scale that ranged from 1 (

Strongly disagree) to 6 (

Strongly agree). Scores are added up, altogether or within a subscale, to compute a total overall or subscale score. Higher scores are indicative of a stronger connection to one’s ethnic identity. Previous evaluations of the MEIM have concluded that scores on the measure are psychometrically sound and reliable, with prior research reporting alpha estimates above 0.90 and acceptable fit indices and factor loadings in confirmatory factor analyses. In the current samples, MEIM scores were concluded to be both reliable and structurally sound, with an alpha estimate range of 0.76–0.90 and acceptable EFA results (KMO = 0.926, Chi-square = 3015.48, df = 66,

p < 0.001; Communality range: 0.275–0.686, total variance explained across both factors = 51.34%, and factor loadings of 0.32–0.93 across the two factors).

5.3. Data Analysis

The sample of 533 was randomly split into two smaller samples to conduct two related analyses. First, a series of exploratory factor analyses (EFAs; 39.4% of the sample, n = 210, Sample A) were carried out to better understand the underlying structure of the items put forth for both scales (e.g., to understand how many factors best explained the observed data). Then, a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs; 60.6% of the sample, n = 323, Sample B) were carried out on both scales to confirm the factor structures indicated by the EFAs. A 2-factor, higher-order factor structure was not examined as the scales were made to be used separately and no higher-order factor structure was theorized. Missing data were handled using the expectation–maximization (EM) algorithm. After a Little’s MCAR test indicated that the data were missing completely at random (all ps > 0.05), EM (25 iterations) was used to impute 14.4% to 16.9% of each non-demographic study variable.

6. Results

Our results are interpreted through the lens of Apocalyptic Education, highlighting how the wellness scale operationalizes the framework’s emphasis on cultural and community connectedness.

6.1. Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviations, intercorrelations, and alpha estimates for study variables can be found in

Table 1. Most correlations among study variables were moderate, with values ranging from 0.40 to 0.70. The two correlations not included within this range were correlations between the subscales of ethnic identity and the total ethnic identity score. Relatedly, study variables were neither abnormally skewed (range: 0.39 to 0.79) or kurtotic (range: 0.39 to 1.32) [

78].

6.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

A series of exploratory factor analyses (EFAs) were conducted to examine the underlying structure of the Cultural Connectedness and Community Connectedness scales. The data for Sample A were concluded to be appropriate for an EFA on the basis of (a) the sample being greater than 200, (b) the communalities of all EFAs being mostly moderate (i.e., ≈0.50 on average, see

Table 2), (c) the ratio of variables to factors being >9 for all EFAs, (d) the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measures of Sampling Adequacy being >0.70 for all EFAs (see

Table 2), and (e) all Bartlett’s Tests of Sphericity being significant (all

ps < 0.001) [

79,

80]. Consistent with best practice [

81], all EFAs were carried out using the principal axis factoring extraction method without any rotation (as both scales were theorized as one-factor scales).

For the Cultural Connectedness scale, the first EFA consisted of 13 items. Three reverse-coded items from the initial 16 items were dropped due to several studies indicating that scales that include both positively and negatively worded items have sub-optimal reliability as well as an increased potential for confusion and various forms of bias (e.g., carelessness and confirmation) [

81,

82,

83,

84]. Prior to the interpretation of the EFA results, parallel analysis was conducted alongside an examination of eigenvalues to determine the number of factors to retain [

81]. For this initial EFA, both parallel analysis and the eigenvalue rule of being greater than 1 indicated that a single factor should be retained. In addition, as can be seen in

Table 2, scores from this 13-item scale displayed moderate communality scores 0.40 ≤

x ≤ 0.70; Costello & Osborne, 2005 [

79]), exhibited acceptable factor loadings (i.e., >0.40 [

81], and explained a meaningful amount of the overall variance of the factor. As a result of these findings, combined with an acceptable reliability estimate (see

Table 2), it was concluded that the scores from this 13-item scale were structurally sound as a one-factor solution.

However, in hopes of creating a more robust and slightly shorter measure, a second model was examined (i.e., a 10-item iteration). In the second model, three additional items were dropped from the scale. These items were dropped due to being some of the lowest performing items across the themes that the authors were trying to capture in this scale– cultural identity/background and engagement in cultural practices. After the three items were dropped, a second EFA was conducted. Again, both parallel analysis and the eigenvalue rule indicated that just a single factor should be retained. Further, as can be seen in

Table 2, the results of the second EFA were almost identical to the first. Scores from this 10-item version of the Cultural Connectedness scale exhibited similar communalities and factor loadings as the 13-item version while explaining slightly more overall total variance. Relatedly, the reliability coefficient for these item scores was well above the commonly accepted cutoff of 0.70. Altogether, these results indicate that scores from the 10-item version of the Cultural Connectedness scale were sound and reliable as a one-factor solution.

For the Community Connectedness scale, the first version consisted of 15 items. However, three reverse-coded items were discarded due to the reasons stated above. The remaining 12 items were examined in the first EFA for the Community Connectedness scale. After parallel analysis and the eigenvalue rule indicated that just a single factor should be retained, the EFA yielded mostly moderate communality values and acceptable factor loadings and explained a meaningful amount of the factor (see

Table 2). These results, combined with the high alpha coefficient, indicated that scores from the 12-item version of the Community Connectedness scale were sound as a one-factor solution.

After examining the results of the 12-item solution, three additional items were discarded. These items were dropped due to being some of the lowest-performing items within their respective category. The Community Connectedness scale was created to capture one’s connection to living things, one’s engagement with their community, and one’s sense of belonging within one’s community. The discarded items were superfluous items in the connection to living things category. A final EFA was conducted with the remaining nine items, which yielded identical results to the 12-item version of the Community Connectedness scale. Specifically, parallel analysis and the eigenvalue rule indicated that just a single factor should be retained, and the EFA yielded similar communalities and factor loadings, while scores from the nine-item version explained slightly more overall total variance. Mixed with a high alpha estimate, it was concluded that scores from this nine-item version of the Community Connectedness scale were sound and reliable as a one-factor solution.

Given the similar results across both versions of both scales, the slightly higher total variance accounted for in the two revised scales, and the goal of having short and robust scales, it was decided that the following confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) would focus solely on the 10-item Cultural Connectedness scale and the 9-item Community Connectedness.

6.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Two confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were carried out to examine the structural validity of the factor structure identified by the above EFAs. Consistent with previous research [

85,

86], all CFAs were carried out with the maximum likelihood estimator, and the first item of each scale was set to 1 as an anchor item. Consistent with best practice [

87,

88], multiple fit indices were used to assess the fit of each model. Reported fit indices include two incremental fit indices (i.e., the Comparative Fit Index [CFI] and the Tucker–Lewis Index [TLI]) and an absolute measure of fit (i.e., the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual [SRMR]). Altogether, these measures examine model fit in a host of different ways to account for various weaknesses that each individual measure has (e.g., not taking into account sample size). For the CFI and TLI, values ≥0.90 indicate good fit [

89]. For the SRMR, values ≤0.08 indicate good fit [

90].

The results of the CFAs for both the 10-item Cultural Connectedness scale and the 9-item Community Connectedness scale are presented in

Table 3. As can be seen, scores from both scales exhibited acceptable CFI, TLI, and SRMR values, indicating that both models fit the data well. In addition, scores from both scales displayed acceptable factor loadings and high reliability estimates (see

Table 3). These results, combined with the theoretical framework and research literature presented above, indicate that these two scales are structurally sound and reliable.

6.4. Convergent Validity

A series of correlations were investigated to examine whether the Cultural Connectedness scale and Community Connectedness scale measure one’s connectedness to their culture and community, respectively. The MEIM was used to examine convergent validity as it is an established measure of one’s connectedness to their ethnic identity/culture. Specifically, it measures how much one has explored their relationship to their ethnic identity as well as one’s sense of belonging to their ethnic identity/culture. As can be seen in

Table 1, scores on both measures exhibited a medium to large effect size relationship with all three measures of ethnic identity, indicating that scores from the Cultural Connectedness scale and Community Connectedness scale do capture, to some degree, the extent that one feels connected to their ethnic background and ethnic community.

7. Discussion

In this discussion, we reiterate the foundational role of the Apocalyptic Education (AE) framework in guiding our study, particularly emphasizing how the development and validation of the wellness scale are rooted in AE’s principles. This approach underlines the cultural relevance and community focus of our pedagogical intervention, demonstrating its alignment with critical social science perspectives on education and well-being.

The aim of this study was to develop reliable, structurally sound measures of cultural connectedness and community connectedness for utility with Black youth in education and community health settings. Specifically, the goal was to create a robust, concise measure for each factor that required a short amount of time for completion and was applicable across settings with youth. First, all correlations among study variables were found to be statistically significant (p < 0.001). Correlation effect sizes ranged from medium to very large (i.e., 0.40–0.94), with all correlations between the Community Connectedness scale, Cultural Connectedness scale, and MEIM landing between 0.40 and 0.67. The highest correlations (i.e., 0.88 and 0.94) were in the MEIM combined scores and subscales, which was to be expected with a single-factor measure. It is important to note that the medium to large intercorrelations found between the Community Connectedness scale, Cultural Connectedness scale, and MEIM were to be expected among theoretically related constructs and provide evidence for convergent validity.

Second, the results of the EFAs revealed acceptable factor loadings, and parallel analysis and eigenvalues indicated that the Cultural Connectedness items and Community Connectedness items each loaded onto separate, single factors. After dropping reverse-coded and repetitive items from each scale, results for the 10-item Cultural Connectedness and 9-item Community Connectedness scales continued to indicate acceptable values for factor loadings, communalities, and single-factor retention. The CFAs conducted exhibited good fit indices values (i.e., CFI and TLI ≥ 0.90; SRMR ≤ 0.08) for both the Cultural Connectedness and Community Connectedness scales, indicating that the final surveys were structurally sound and reliable. In addition, alpha coefficients of both scales were above the accepted cutoff of 0.70 and each scale measured a meaningful amount of the variance of the respective factor. Overall, the results of these analyses indicate that the Cultural Connectedness and Community Connectedness scales developed in the present study are structurally sound and reliable measures of their respective constructs. As such, the Cultural Connectedness and Community Connectedness scales are new instruments that can be used in future research to measure the degree to which youth feel connected to their ethnic background and community.

8. Conclusions

The findings of this study herald a significant advancement in the assessment of cultural and community connectedness among Black youth in educational and community health settings. Particularly, our examination of how culturally relevant pedagogy correlates with enhanced health metrics in BIPOC youth represents an important contribution, underscoring the potential for broader impacts on academic discourse. The development of reliable, structurally sound measures like the Cultural Connectedness and Community Connectedness scales represents more than just a novel methodological contribution to education; it opens new (and remembered) avenues for understanding and protecting the wellness of Black and other Indigenous young people.

The robust nature of these scales supports confident utilization across various settings. This adaptability is crucial for educators, advocates, and community health practitioners seeking to understand and foster a deeper sense of connection and cultural revitalization among youth. These scales offer a quantifiable means to assess the impact of various interventions and programs. Moreover, the brevity and conciseness of these measures address practical constraints often encountered in educational and health settings, making them more feasible for regular use. This aspect is particularly important as it enables ongoing monitoring and assessment without causing significant disruption or requiring excessive time commitments from participants.

The implications of this study extend beyond the academic realm, potentially influencing policy and practice. In educational settings, these scales could guide curriculum development and educational practices that more effectively resonate with and support the cultural ways of being and learning of Black and other Indigenous youth. In community health, they could inform targeted interventions and support services that acknowledge and strengthen relationships, potentially improving mental health and well-being.

Furthermore, the validation of these scales sets a precedent for future research in cultural and community connectedness. They provide a foundational tool for comparative studies across different demographic groups, enhancing our understanding of the universality and specificity of these constructs.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are also several limitations that should be noted when considering the development and validation of the present scales. For instance, this was the first attempt to create this measure and is necessarily a relatively small example of the utility of the instrument. We suggest that future relevant studies continue using the instrument in order to provide further evidence of validity and reliability. Secondly, although the development of these scales originates in an ongoing longitudinal study observing the connection between culturally relevant teaching practices and improved health outcomes for children, no examination has occurred yet using the instrument to explore its constructs related to health implications for youth. We recommend further research that utilizes this instrument to explore health outcomes (i.e., pre- and post-assessment in classroom practice in place of grading to gauge well-being as a measurement of success, snapshot assessments of particular groups’ health/wellbeing, studies concerned with relationships between cultural practice and well-being). Studies such as these might aid in the assessment of potential health implications when educational interventions, including youth suicide prevention efforts, center on and protect young people’s cultural, communal, and ancestral vitality without compromise.

In conclusion, the Cultural Connectedness and Community Connectedness scales stand as valuable contributions to our collective efforts to support and empower Black youth. By offering reliable, practical, and meaningful measures, this study paves the way for a more nuanced understanding of and effective support for the cultural and community ties that shape the experiences and well-being of young individuals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: K.T.W., T.M., E.-A.G. and D.D.; methodology: K.T.W., T.M., E.-A.G. and D.D.; software: K.T.W., T.M., E.-A.G. and D.D.; validation: K.T.W., T.M., E.-A.G. and D.D.; formal analysis: K.T.W., T.M., E.-A.G. and D.D.; investigation: K.T.W., T.M., E.-A.G. and D.D.; resources: K.T.W., T.M., E.-A.G. and D.D.; data curation: K.T.W., T.M., E.-A.G. and D.D.; writing—original draft preparation: K.T.W., T.M., E.-A.G. and D.D.; writing—review and editing: K.T.W., T.M., E.-A.G. and D.D.; visualization: K.T.W., T.M., E.-A.G. and D.D.; and project administration: K.T.W., T.M., E.-A.G. and D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The studies detailed in this paper were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of California, Berkeley (2016-11-9346 on 10/2/2017) and San Jose State University (22092 on 06/01/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to our pre-conditional agreement with study participants to take all necessary precautions to protect their anonymity.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

TL ratio (pre and post).

Figure A1.

TL ratio (pre and post).

Figure A2.

Percent increase in telomere length (1 year).

Figure A2.

Percent increase in telomere length (1 year).

Note

| 1. | The racial designation “white” is not capitalized throughout the piece since the term is not a collective title chosen by a marginalized group of people. Capitalizing both “white” and “Black” implies symmetry in status that is not a historical, social, or structural reality. The designation “Black” in numerous European and Arabic languages was first utilized as a weapon of racialization and dehumanization against millions of African captives and causalities of the Arabic and Transatlantic Slave Trade. In the afterlife of slavery, Black has been re-appropriated by the descendants of captives within and beyond the US as an identity marker, sociopolitical rallying coordinate, and everything in between in response to the ever-present anti-blackness that saturates their experiences. Such renaming is a resistance response as well as a response of community affirmation. Conversely, Given its sociohistorical ontology, the term “white” can only reasonably be used (and capitalized) in a similar way to “Black” as an implicit or explicit (conscious or unconscious) endeavor aligned with resurgent white supremacist and nationalist sentiments. |

References

- Sasson, I.; Hayward, M.D. Association Between Educational Attainment and Causes of Death Among White and Black US Adults, 2010–2017. JAMA 2019, 322, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N. Does racism harm health? Did child abuse exist before 1962? On explicit questions, critical science, and current controversies: An ecosocial perspective. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronimus, A.T.; Pearson, J.A.; Linnenbringer, E.; Schulz, A.J.; Reyes, A.G.; Epel, E.S.; Lin, J.; Blackburn, E.H. Race-ethnicity, poverty, urban stressors, and telomere length in a Detroit community-based sample. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2015, 56, 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie, T.; Watson, K. Remembering an apocalyptic education: Revealing life beneath the waves of black being. Root Work J. 2020, 1, 14–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.; Marie, T. Somewhere Between a Rock and an Outer Space: Regenerating Apocalyptic Education. J. Futures Stud. 2022, 26, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, K.T. Revealing and Uprooting Cellular Violence: Black Men and the Biopsychosocial Impact of Racial Microaggressions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shujaa, M.J. Education and schooling: You can have one without the other. Urban Educ. 1993, 27, 328–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shujaa, M.J. Too Much Schooling, Too Little Education: A Paradox of Black Life in White Societies; Africa World Press: Trenton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, O. Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Somé, M.P. The Healing Wisdom of Africa: Finding Life Purpose through Nature, Ritual, and Community; Penguin: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ani, M. Yurugu: An African-Centered Critique of European Cultural Thought and Behavior; Africa World Press: Trenton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, R.A. What is a social determinant of health? Back to basics. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 10, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet Public Health. Education: A neglected social determinant of health. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie, T. Schools are where trees & children’s livelihoods go to die: A teacher’s reflection of revitalizing land-based education. Occas. Pap. Ser. 2023, 2023, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Motley, R.O., Jr.; Joe, S.; McQueen, A.; Clifton, M.; Carlton-Brown, D. Development, construct validity, and measurement invariance of the Modified Classes of Racism Frequency of Racial Experiences Measure (M-CRFRE) to capture direct and indirect exposure to perceived racism-based police use of force for Black emerging adults. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2023, 29, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, F.; Lambert, S.; Rose, T. Ethnic–racial socialization as a moderator of associations between discrimination and psychosocial well-being among African American and Caribbean Black adolescents. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2022, 28, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaton, E.K.; Caldwell, C.H.; Sellers, R.M.; Jackson, J.S. The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1288–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cokley, K.O. Racial(ized) identity, ethnic identity, and Afrocentric values: Conceptual and methodological challenges in understanding African American identity. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.P.; Dumas, T.M.; Merrin, G.J.; Espelage, D.L.; Tan, K.; Madden, D.; Hong, J.S. Examining the pathways between bully victimization, depression, academic achievement, and problematic drinking in adolescence. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2018, 32, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, M.D.; Guivernau, M.; Kim, M.-S.; Newton, M.; Gano-Overway, L.A.; Magyar, T.M. Youth perceptions of a caring climate, emotional regulation, and psychological well-being. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2012, 1, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesch, S.C.; Duangado, K.M.; Vaughn, A.A.; Aldridge, A.A.; Villodas, F. Dispositional hope and the propensity to cope: A daily diary assessment of minority adolescents. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2010, 16, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetter, A.K.; Thompson, M.N. The impact of historical loss on Native American college students’ mental health: The protective role of ethnic identity. J. Couns. Psychol. 2023, 70, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neblett, E.W., Jr.; Banks, K.H.; Cooper, S.M.; Smalls-Glover, C. Racial identity mediates the association between ethnic-racial socialization and depressive symptoms. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2013, 19, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Bassett, S.M.; So, S.; Voisin, D.R. Family stress and youth mental health problems: Self-efficacy and future orientation mediation. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2019, 89, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, R.; Johnson, F.N.; Winter, T.; Jose, P.E. The Māori Cultural Embeddedness Scale (MaCES): Initial evidence of structural validity. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2023, 29, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, H.; Mosley-Howard, G.S.; Baldwin, D.; Ironstrack, G.; Rousmaniere, K.; Schroer, J.E. Cultural revitalization as a restorative process to combat racial and cultural trauma and promote living well. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2019, 25, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Andreotti, V.; Stein, S.; Ahenakew, C.; Hunt, D. Mapping interpretations of decolonization in the context of higher education. Decolonization Indig. Educ. Soc. 2015, 4, 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Solórzano, D. Critical Race Theory Part I [Video]. Youtube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iti9NUDrFd8&ab_channel=stmaryscaedu (accessed on 5 April 2013).

- Fu-Kiau, K.K.B. African Cosmology of the Bântu-Kôngo: Tying the Spiritual Knot: Principles of Life & Living; Athelia Henrietta Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- simple ant. Fugitive ecologies: Finding freedom in the wilderness. Root Work J. 2020, 1, 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, G. Look to the Mountain: An Ecology of Indigenous Education; Kivaki Press: Durango, CO, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerer, R. Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses; Oregon State University Press: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerer, R. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants; Milkweed Editions: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, T. Beloved; Vintage International: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Spillers, H. Mama’s baby, papa’s maybe: An American grammar book. Diacritics 1987, 17, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynter, S. Afterword: Beyond Miranda’s meanings: Un/silencing the ‘demonic ground’of Caliban’s ‘woman. In Out of the Kumbla: Caribbean Women and Literature; Davies, C.B., Fido, E.S., Eds.; Africa World Press: Trenton, NJ, USA, 1990; pp. 355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Wynter, S. Unsettling the coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument. New Centen. Rev. 2003, 3, 257–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynter, S. Beyond liberal and Marxist Leninist feminisms: Towards an autonomous frame of reference. CLR James J. 2018, 24, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, S.V. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, C. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wilderson, F.B., III. Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of US Antagonisms; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D. Faces at the Bottom of the Well: The Permanence of Racism; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dancy, T.E.; Edwards, K.T.; Earl Davis, J. Historically white universities and plantation politics: Anti-blackness and higher education in the black lives matter era. Urban Educ. 2018, 53, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustaffa, J.B. Mapping violence, naming life: A history of anti-Black oppression in the higher education system. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2017, 30, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sojoyner, D.M. First Strike: Educational Enclosures in Black Los Angeles; U of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sojoyner, D.M. Another life is possible: Black fugitivity and enclosed places. Cult. Anthropol. 2017, 32, 514–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovall, D. Are we ready for ‘school’ abolition?: Thoughts and practices of radical imaginary in education. Taboo J. Cult. Educ. 2018, 17, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, W.H. The White Architects of Black Education: Ideology and Power in America, 1865–1954; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Woodson, C.G. The Mis-Education of the Negro; The Associated Publishers: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sizemore, B.A. The politics of curriculum, race, and class. J. Negro Educ. 1990, 59, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campt, T.M. Black visuality and the practice of refusal. Women Perform. A J. Fem. Theory 2019, 29, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, S. Refusing the university. In Toward What Justice? Tuck, E., Yang, K.W., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Macias, E. From potential “Nini” to “Drop Out”: Undocumented young people’s perceptions on the transnational continuity of stigmatizing scripts. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shange, S. Progressive Dystopia: Abolition, Antiblackness, and Schooling in San Francisco; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, A.S. Raising Free People: Unschooling as Liberation and Healing Work; PM Press: Binghamton, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cariaga, S. Grief work: Being with and moving through a resistance to change in teacher education. Dialogue/En Diálogo 2023, 1, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovall, D. On knowing: Willingness, fugitivity and abolition in precarious times. J. Lang. Lit. Educ. 2020, 16, n1. [Google Scholar]

- Lesure, J. The Problem with Using Proximity & Poverty to Dismiss the Fallacies of ‘Black-on-Black Crime’. Racebaitr, 2020. Available online: https://racebaitr.com/2020/08/05/the-problem-with-using-proximity-poverty-to-dismiss-the-fallacies-of-black-on-black-crime/ (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Taylor, E.R. If We Must Die: Shipboard Insurrections in the Era of the Atlantic Slave Trade; LSU Press: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tello, J. (Host). The Four, Rooted Teachings of Life [Audio Podcast Episode]. Healing Generations. Available online: https://www.buzzsprout.com/1056736/5499742-jerry-tello-the-four-rooted-teachings-of-life (accessed on 22 September 2020).

- Marshall, Y. An Appeal—Bring the Maroon to the Foreground in Black Intellectual History. Black Perspectives, 2020. Available online: https://www.aaihs.org/an-appeal-bring-the-maroon-to-the-foreground-in-black-intellectual-history/ (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Winston, C. Maroon Geographies. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2021, 111, 2185–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, C. How to Lose the Hounds: Maroon Geographies and a World beyond Policing; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari, C.R. Research Methodology: Methods & Techniques; New Age International: Delhi, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fanon, F. Black Skin, White Masks; Grove Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, D. A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging; Vintage Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, D. Practical Rules for the Management and Medical Treatment of Negro Slaves in the Sugar Colonies; Vernor and Hood: London, UK, 1803. [Google Scholar]