Rural Research and Development Corporations’ Connection to Agricultural Industry School Partnerships

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do RRDCs describe their role in the implementation of ISPs?

- How do RRDCs connect and influence other parts of the ecological system regarding ISPs?

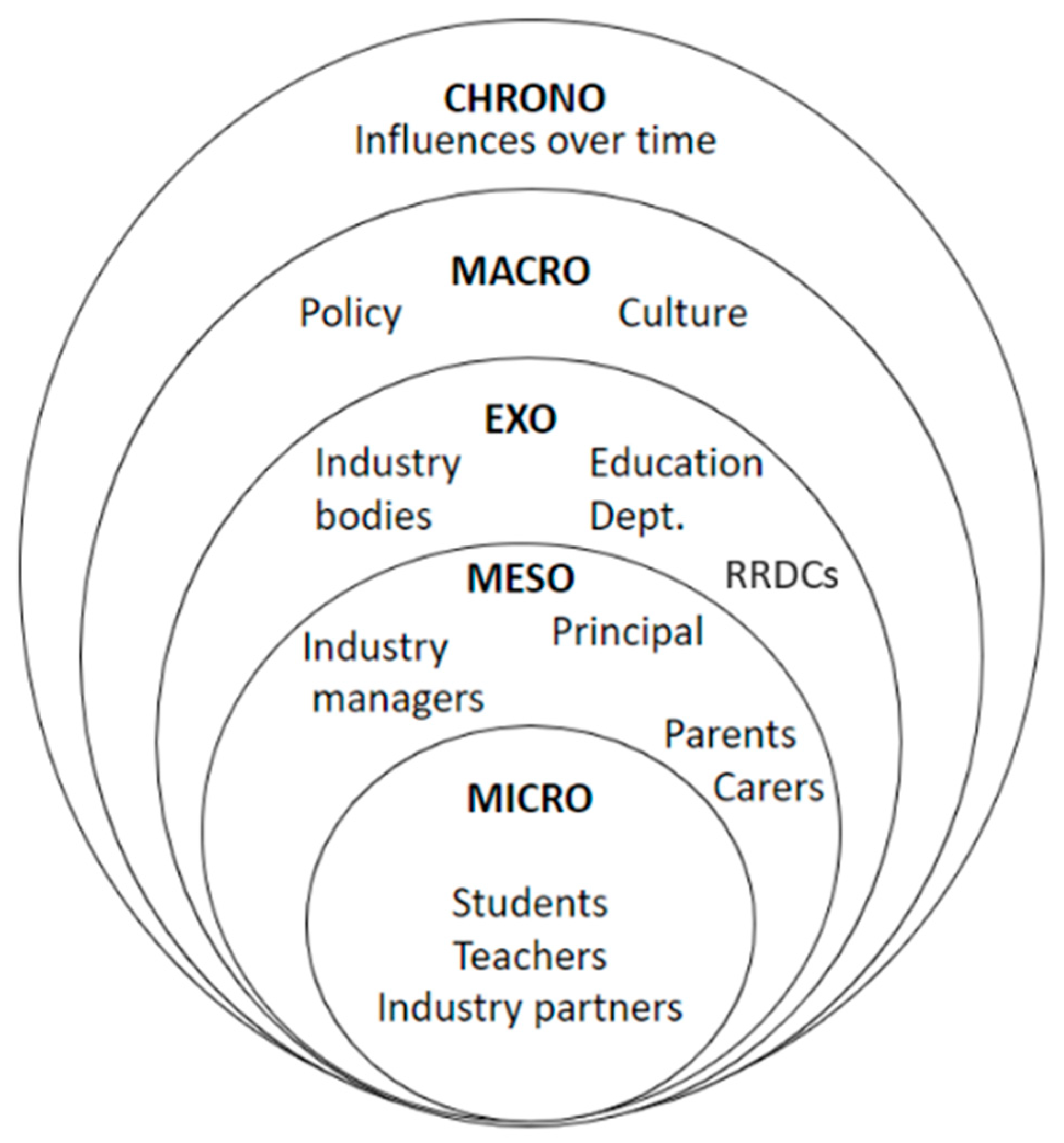

Ecological Systems Theory (EST)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Documents—Strategic and Annual Operating Plans

2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

3. Results

3.1. Strategic Plans and Annual Operating Plans

3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

3.2.1. ISPs Are Important for Industry Sustainability

It then may help us when we come around to needing community support for things like continued access to water, nutrients, or increasing the price of [product] because we’ve had a hailstorm, the community there might say, you know what I am willing to, you know, [buy] the ugly [produce].(RRDCE9)

You’re actually building community trust, as well. I think, you know, if you’re hitting on the right key messages around sustainable production, and all of those bits and pieces, I think it goes a long way to build community trust.(RRDCE11)

3.2.2. RRDCs Are Informally Involved in ISPs

And [an] ISP is not in our plan. I guess, as we go down to look at our everyday operational activities, yeah, I guess we do it in an informal way, indirect way. We’re not involved in a formal way at this point.

We are a very small team with a very small budget, and we have a lot of other priorities, and things that are important and urgent, and then there’s important and not urgent and I think schools’ programs fit in the important but not urgent, and so they probably don’t have as much focus when you’ve got a small, small budget.

3.2.3. Who Can Address the ISP Solution to This Wicked Workforce Problem?

Maybe the schools need to be encouraged to think about what’s growing out and in area and reach out to growers as well. And for them, it’s about maybe saying, well, here’s who to contact to even find out who’s paddock that is that you keep driving past. So maybe that’s where we say, oh come to [RRDC], and … I’ll direct you on to [the relevant industry body], and they can tell you what the grower is and, you know, connect people.

Our industry associations are really important. So, we have multiple tiers of that here. So, we’ve got [industry body], who are the industry body, national industry body, and then there’s state-based under that, and then there’s local based under that, and then there’s, you know, regional based under that. So, there’s this huge kind of structure that we can leverage.

3.2.4. Collaboration Is Key

That’s why we partner with other places to leverage that, I think it’s all about collaboration, I don’t think that we can see ourselves as just the [commodity] industry. I think we have to collaborate and make sure that we’re all working together with that common goal. Because we, you know, it’s just too difficult to do it otherwise.(RRDCE15.4)

I think if we had a coordinated approach, would be very beneficial as well. So, I think you could spend a lot of money… investing in promoting agriculture, though I think the more streamlined we can do it the more… bang for buck we would get as well.(RRDCE14).

So, I believe that for this to be truly remarkable, which it needs to be, you know, because we’re competing against those Navy ads (Royal Australian Navy advertising campaigns), and they’re bloody attractive to people, right. So, if we really want to do a good job of this, it needs a significant investment. And I think that it is, it needs a collective for, and I don’t know whether it’s like an organization that is placed to like, bring a room together, but actually think it’s everyone’s responsibility.

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Education Council. National STEM School Education Strategy; Department of Education, Skills and Employment: Canberra, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, S.; MacDonald, A.; Danaia, L.; Wang, C. An analysis of Australian STEM education strategies. Policy Futures Educ. 2019, 17, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, J.K.; Cosby, A.; Power, D.; Fogarty, E.S.; Harreveld, B. A Systematic Review of the Emergence and Utilisation of Agricultural Technologies into the Classroom. Agriculture 2022, 12, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torii, K. Connecting the Worlds of Learning and Work: Prioritising School-Industry Partnerships in Australia’s Education System; Mitchell Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, L.; Kelly, H. STEM into industry–brokering relationships between schools and local industry. Curric. Perspect. 2020, 40, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattison, N.P. Powerful Partnership: An Exploration of the Benefits of School and Industry Partnerships for STEM Education. Teach. Curric. 2021, 21, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, J. School-Business Partnerships: A Study of Stakeholder Perspectives. Ph.D. Dissertation, Immaculata University, Immaculata, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, B.; Sieben, R.; Unsworth, P. STEM Education in Australia: Impediments and Solutions in Achieving a STEM-Ready Workforce. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Council. The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration; Department of Education Skills and Employment: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- PhillipsKPA. Unfolding Opportunities: A Baseline Study of School-Business Relationships in Australia. Final Report; Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations: Canberra, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Azarias, J.; Nettle, R.; Williams, J. National Agricultural Workforce Strategy: Learning to Excel; National Agricultural Labour Advisory Committee: Canberra, Australia, 2020.

- Bochtis, D.; Benos, L.; Lampridi, M.; Marinoudi, V.; Pearson, S.; Sørensen, C.G. Agricultural Workforce Crisis in Light of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation. The Future of Food and Agriculture—Trends and Challenges; Food and Agriculture Organisation: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Head, B.W.; Alford, J. Wicked Problems: Implications for Public Policy and Management. Adm. Soc. 2015, 47, 711–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, W.J.R.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Williams, R.J.; Gill, T.B. If you study, the last thing you want to be is working under the sun: An analysis of perceptions of agricultural education and occupations in four countries. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosby, A.; Manning, J.K.; Lovric, K.; Fogarty, E.S. The future agricultural workforce—is the next generation aware of the abundance of opportunities? Farm Policy J. 2022, 19, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cosby, A.; Manning, J.; Power, D.; Harreveld, B. New Decade, Same Concerns: A Systematic Review of Agricultural Literacy of School Students. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovar, K.A.; Ball, A.L. Two Decades of Agricultural Literacy Research: A Synthesis of the Literature. J. Agric. Educ. 2013, 54, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Experimental Ecology of Education. Educ. Res. 1976, 5, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, M. Industry-School Partnerships: An Ecological Case Study to Understand Operational Dynamics. Ph.D. Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, M.; Pillay, H. Industry-School Partnerships: An Ecological Approach. Int. J. Arts Sci. 2013, 6, 121. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dea, M.; Cosby, A.; Manning, J.; McDonald, N.; Harreveld, B. Who, how and why? The nature of industry participants in agricultural industry school partnerships in Gippsland, Australia. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, M.; Cosby, A.; Manning, J.; McDonald, N.; Harreveld, B. Industry perspectives of industry school partnerships: What can agriculture learn? Aust. Int. J. Rural Educ. 2022, 32, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, J. Using Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory to understand community partnerships: A historical case study of one urban high school. Urban Educ. 2011, 46, 987–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Agriculture Fisheries and Forestry. Rural Research and Development Corporations. Available online: https://www.agriculture.gov.au/agriculture-land/farm-food-drought/innovation/research_and_development_corporations_and_companies (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Australian Government Department of Agriculture Fisheries and Forestry. About Levies and the Levy System. Available online: https://www.agriculture.gov.au/agriculture-land/farm-food-drought (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Rural R&D Corporations. About. Available online: http://www.ruralrdc.com.au/about/ (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Rutledge, K.; McDaniel, M.; Teng, S.; Hall, H.; Ramroop, T.; Sprout, E.; Hunt, J.; Boudreau, D.; Costa, H. Ecosystem. Available online: https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/ecosystem/ (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Taylor, G.; Ali, N. Learning and Living Overseas: Exploring Factors that Influence Meaningful Learning and Assimilation: How International Students Adjust to Studying in the UK from a Socio-Cultural Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bipath, K.; Tebekana, J.; Venketsamy, R. Leadership in Implementing Inclusive Education Policy in Early Childhood Education and Care Playrooms in South Africa. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, N.; O’Toole, L.; Halpenny, A.M. Introducing Bronfenbrenner: A Guide for Practitioners and Students in Early Years Education, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Agriculture Fisheries and Forestry. Farming, Food and Rural Support. Available online: https://www.agriculture.gov.au/agriculture-land/farm-food-drought (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G.A. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Meat Processors Corporation. Annual Operating Plan 2023–2024; Australian Meat Processors Corporation: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Meat Processors Corporation. Strategic Plan 2020–2025; Australian Meat Processors Corporation: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Wool Innovation Limited. Strategic Plan 2022–2025; Australian Meat Processors Corporation: Sydney, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Wool Innovation Limited. Annual Operating Plan 2023–2024; Australian Wool Innovation Limited: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dairy Australia. Strategic Plan 2020–2025; Dairy Australia: Southbank, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dairy Australia. Annual Operating Plan 2023/24; Dairy Australia: Southbank, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Eggs. Annual Operating Plan 2022/23; Australian Eggs: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Eggs. Strategic Plan 2021–2026; Australian Eggs: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Forest & Wood Products Australia Limited. Strategic Plan 2023–2028; Forest & Wood Products Australia Limited: Melbourne, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Forest & Wood Products Australia Limited. 21/22 Annual Operating Plan; Forest & Wood Products Australia Limited: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Livecorp. Strategic Plan 2025; Livecorp: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Livecorp. 2023–2024 Annual Operational Plan; Livecorp: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton Research and Development Corporation. Annual Operational Plan 2023–2024; Cotton Research and Development Corporation: Narrabri, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton Research and Development Corporation. Strategic RD&E Plan 2023–2028; Cotton Research and Development Corporation: Narrabri, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. Research and Development Plan 2020–2025; Fisheries Research and Development Corporation: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. Annual Operational Plan 2022–2023; Fisheries Research and Development Corporation: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Grains Research and Development Corporation. Annual Operational Plan 2023–2024; Grains Research and Development Corporation: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Grains Research and Development Corporation. Research, Development & Extension Plan 2023–2028; Grains Research and Development Corporation: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wine Australia. Annual Operational Plan 2023–2024; Wine Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wine Australia. Strategic Plan 2020–2025; Wine Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Meat & Livestock Australia. Annual Investment Plan 2023–24; Meat & Livestock Australia: Syndney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Meat & Livestock Australia. Strategic Plan 2025; Meat & Livestock Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Pork Limited. Annual Operating Plan 2023–2024; Australian Pork Limited: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Pork Limited. Strategic Plan 2020–2025; Australian Pork Limited: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sugar Research Australia. Strategic Plan 2021–2026; Sugar Research Australia: Indooroopilly, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sugar Research Australia Limited. Annual Operational Plan 20/21; Sugar Research Australia: Indooroopilly, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Almond Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Almond Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Apple and Pear Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Apple and Pear Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Avocado Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Avocado Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Banana Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Banana Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Berry Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Berry Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Cherry Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Cherry Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Chestnut Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Chestnut Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Citrus Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Citrus Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Custard Apple Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Custard Apple Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Dried Grape Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Dried Grape Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Dried Tree Fruit Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Dried Tree Fruit Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Lychee Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Lychee Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Macadamia Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Macadamia Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Mango Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Mango Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Melon Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Melon Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Mushroom Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Mushroom Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Nashi Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Nashi Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Nursery Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Nursery Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Olive Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Olive Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Onion Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Onion Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Papaya Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Papaya Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Passionfruit Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Passionfruit Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Persimmon Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Persimmon Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Pineapple Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Pineapple Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Pistachio Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Pistachio Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Potato Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Potato Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Processing Tomato Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Processing Tomato Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Prune Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Prune Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Summerfruit Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Summerfruit Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Sweetpotato Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Sweetpotato Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Table Grape Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Table Grape Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Turf Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Turf Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Vegetable Annual Investment Plan 2022/23; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Horticulture Innovation Australia. Vegetable Strategic Investment Plan 2022–2026; Horticulture Innovation Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- AgriFutures Australia. Annual Operational Plan 2023–2024; Agrifutures Australia: Wagga Wagga, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- AgriFutures Australia. Research and Innovation Strategic Plan 2022–2027; Agrifutures Australia: Wagga Wagga, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Otter.ai. Why Otter.ai. Available online: https://Otter.ai (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo (released in March 2020). Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, P.; Shepheard, M.L. What Is Meant by the Social Licence? CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, Australia, 2011; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations. Realising Potential: Businesses Helping Schools to Develop Australia’s Future; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Cosby, A.; Manning, J.; Trotter, M. TeacherFX-building the capacity of stem, agriculture and digital technologies teachers in western australia. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Math. Educ. 2019, 27, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AiGroup. Strengthening School-Industry STEM Skills Partnerships; Final Project Report; The Australian Industry Group: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Malin, J.R.; Hackmann, D.G.; Scott, I.M. Cross-sector collaboration to support college and career readiness in an urban school district. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2020, 122, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, H.; Watters, J.J.; Hoff, L.; Flynn, M. Dimensions of effectiveness and efficiency: A case study on industry–school partnerships. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2014, 66, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment. Delivering Ag2030; Australian Government Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment: Canberra, Australia, 2020.

- Pratley, J.; Graham, S.; Manser, H.; Gilbert, J. The employer of choice or a sector without workforce? Farm Policy J. 2022, 19, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Dawson, D.; Fleming-Munoz, D.; Schleiger, E.; Horton, J. The Future of Australia’s Agricultural Workforce; CSIRO Data61: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst & Young. Agricultural Innovation—A National Approach to Grow Australia’s Future; Department of Agriculture and Water Resources: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- Hampton, J.O.; Jones, B.; McGreevy, P.D. Social License and Animal Welfare: Developments from the Past Decade in Australia. Animal 2020, 10, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plunkett, M.; Dyson, M. ‘Broadening Horizons’: Raising Youth Aspirations Through a Gippsland School/Industry/University Partnership. In Educational Researchers and the Regional University: Agents of Regional-Global Transformations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Odom, S.L.; Vitztum, J.; Wolery, R.; Lieber, J.; Sandall, S.; Hanson, M.J.; Beckman, P.; Schwartz, I.; Horn, E. Preschool inclusion in the United States: A review of research from an ecological systems perspective. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2004, 4, 17–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh Mohammadabadi, A.; Ketabi, S.; Nejadansari, D. Factors influencing language teacher cognition: An ecological systems study. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2019, 9, 657–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RRDC | Number of Mentions | Notes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educa (tion/te) | Student | School | Train | Learn | Teach | ||

| 1. Australian Meat Processors Corporation (AMPC) [39,40] | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | The strategic plan stated that they aimed to “develop a schools program starting with secondary school students to introduce them to all the opportunities that the processing industry has to offer” [39] (p. 6). |

| 2. Australian Wool Innovation (AWI) [41,42] | 16 | 14 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 0 | References to several programs including the following: -Learn about Wool lesson plans -Wool4School design competition -Woolmark Learning Centre The strategic plan also noted that the field station could be used for school activities. |

| 3. Dairy Australia [43,44] | 11 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 1 | The 2023/24 AOP included a school engagement project with the following activities listed: -“Educate school children on the value of dairy including the health benefits of dairy and building an understanding of the way food is produced. Promoting careers in dairy will also be a focus. -Continue to leverage the Discover Dairy education platform providing curriculum linked resources to school teachers and children. -Engage primary school children through the eight-week program, Picasso Cows. Seek further income opportunities to leverage this program. -Continue to leverage the Discover Dairy education platform and resources linked to the curriculum. -Leverage messages through existing initiatives such as virtual classrooms, virtual reality and the Life Education and Primary Industry Education Foundation Australia partnership. -Engage with regions to further amplify this message to school children in their regions and work with ambassadors to promote dairy to a younger audience” [44] (p. 30). |

| 4. Eggs Australia [45,46] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5. Forest and Wood Products Australia (FWPA) [47,48] | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 14 | 12 | Numerous references to ForestLearning teacher education program. |

| 6. Livecorp [49,50] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7. Cotton RDC (CRDC) [51,52] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8. Fisheries RDC (FRDC) [53,54] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9. Grains RDC (GRDC) [55,56] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PIEFA membership investment is noted in the AOP. |

| 10. Wine Australia [57,58] | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | The AOP stated “we will continue to work with the school, vocational and higher education sectors as well as Australian Government-funded initiatives addressing workforce and labour issues across agriculture to promote pathways to the grape and wine sector as a career of choice” [58] (p. 15). |

| 11. Meat & Livestock Australia (MLA) [59,60] | 10 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 7 | The strategic plan stated “The ‘school education’ product group engages schools and teachers through education partnerships and the promotion of the newly developed national curriculum aligned teaching resources, focusing on animal welfare, environmental management and the role of red meat in a healthy balanced diet. Initiatives include: -membership of Primary Industries Education Foundation Australia (PIEFA) and subscriptions to education service providers such as Kids Media and Education Australia to promote the Australian Good Meat educational resources–membership investments also support the opportunity for access to teacher and student insights into preferred teaching methods, resource needs and sentiment towards teaching Australian agriculture in the classroom -promotion of school education resources through participating at events and social media channels that target teachers and/or students -host online educational programs featuring Red Meat Ambassadors”. [59] (p. 63) |

| 12. Australian Pork Limited (APL) [61,62] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 13. Sugar Research Australia (SRA) [63,64] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 14. Horticulture Innovation (HIA) * [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130] | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Banana fund investment plan identified an Australian Bananas school partnership—nutrition program in partnership with Life Education Australia. The berry fund investment plan identified a berry industry careers program which states that it could include a school leaver mentoring program. |

| 15. Agrifutures Australia [131,132] | 3 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | The AOP identified the following projects: -PIEFA Educational Materials for the Australian Chicken Meat Industry -Cultivating the next generation: the role of school-based educators in promoting agricultural careers -Precision Agriculture using “Real Data” in Education -Developing students and staff while improving farm efficiencies -The aim of this project is to build the capacity of students to utilise and interpret a range of data sets using GPS technology on livestock monitoring. -All About Alpacas: Teaching Resources for Australian Schools -Cultivating the next generation: the role of school-based educators in promoting agricultural careers -Hagley Farm School Agricultural Learning Centre The following were identified as planned activities in the AOP: -Conduct a cross-sector project in determining the future workforce requirements for agriculture, forestry and fisheries industries. Agriculture Career Advisory Services: Phase 1: identify and report on the current perceptions and knowledge within secondary schools of career opportunities in the Australian Agriculture (including fisheries, forestry and horticulture) sector. -Identify current perceptions and knowledge within NSW Government, Catholic and Independent secondary schools of career opportunities in the Australian agriculture sector. [131] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

O’Dea, M.; Cosby, A.; Manning, J.K.; McDonald, N.; Harreveld, B. Rural Research and Development Corporations’ Connection to Agricultural Industry School Partnerships. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030271

O’Dea M, Cosby A, Manning JK, McDonald N, Harreveld B. Rural Research and Development Corporations’ Connection to Agricultural Industry School Partnerships. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(3):271. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030271

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Dea, Molly, Amy Cosby, Jaime K. Manning, Nicole McDonald, and Bobby Harreveld. 2024. "Rural Research and Development Corporations’ Connection to Agricultural Industry School Partnerships" Education Sciences 14, no. 3: 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030271

APA StyleO’Dea, M., Cosby, A., Manning, J. K., McDonald, N., & Harreveld, B. (2024). Rural Research and Development Corporations’ Connection to Agricultural Industry School Partnerships. Education Sciences, 14(3), 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030271