Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the Collaborative and Proactive Solutions (CPS) intervention in an alternative educational setting for students with behavioural problems. The effect of the CPS intervention on students’ off-task behaviour was studied using a single-subject experimental design that included two students with behavioural problems via systematic direct observations and direct behaviour ratings. The usability of the CPS intervention was investigated through questionnaires and interviews with the participating students and teacher assistant. The results revealed no significant effects of the CPS intervention on students’ off-task behaviour. The students and teacher assistant viewed the CPS intervention as acceptable but the teacher assistant’s ratings of the feasibility of the intervention were lower, together with the ratings of the extent to which the intervention matched the socio-political climate of the educational setting.

1. Introduction

Children with behavioural problems constitute a particularly vulnerable group in education that requires highly tailored interventions in school settings [1,2,3]. Disruptive behaviours put children at increased risk of conflicts with their peers and teachers, potentially reducing their sense of belonging at school [4]. Children with behavioural problems, regardless of the presence of a clinical diagnosis or not, also run a higher risk of being subject to disciplinary measures, which lead to less instructional time necessary to succeed academically. Taken together, these circumstances place the children at a heightened risk of school alienation, school dropout and unemployment from a long-term perspective. Thus, it is crucial that well-functioning support systems are in place.

Research on current support systems and instructional practices reveals multiple challenges. Studies show that children with behavioural problems report feeling a lack of support, poor school climate and instructional practices that are not conducive to school engagement [5,6]. Teacher relationships are characterised more by conflict and less by closeness [4,5,6,7,8] and teachers report negative attitudes to children with behavioural problems [9] and have a limited repertoire of instructional strategies [10]. These shortcomings further accentuate the need for effective interventions in school settings.

Previous research on interventions for children with behavioural problems has outlined a number of effective interventions, including Positive Behavioural Interventions and Supports (PBISs), self-regulation and self-management, as well as social skills interventions [11,12,13]. At the same time, a call for more research and new innovative intervention approaches has been articulated with regard to the “complex nature” of the challenges that children encounter at school [14]. One promising line of research in this regard concerns interventions that focus on self-determination, in which students are actively engaged in decision-making processes to promote self-knowledge, self-advocacy, independence and autonomy [15,16]. The proposed study aims to evaluate Collaborative and Proactive Solutions (CPS), an intervention that addresses teacher–child relationships while also engaging students in the problem-solving processes regarding their situation at school.

1.1. Previous Research on Collaborative and Proactive Solutions

Collaborative and Proactive Solutions (CPS) is a psychosocial intervention for children and youth with behavioural problems and has been evaluated in a number of contexts, including families, schools and therapeutic facilities [17]. In several randomised controlled trials, the model, founded by Ross Greene [18,19], has been shown to be effective in reducing externalising behaviour. Even though established models of behavioural support, such as the PBIS framework, emphasise a transactional view of understanding the development of challenging behaviours in children, the CPS model also provides a framework of how to practically change the dynamics between the caregiver and the child in such a way that both parties are equally involved and collaborate in the process of understanding and resolving the problems at hand [20]. Also, as Greene and Winkler [17] point out, CPS acknowledges a child’s lagging skills, such as flexibility, frustration tolerance and problem solving, as vital parts that the caregiver must take into account when helping the child. This view supports caregivers when responding to oppositional behaviour in a “less personalized, less reactive, and more empathic manner” [17]. The primary component of the CPS assessment and intervention is to first identify a child’s lagging skills and their associated unsolved problems, and then help caregivers and the child solve such problems collaboratively and proactively in a problem-solving conversation. The aim of such conversations is to promote child self-advocacy, as well as to give equal importance to both child and adult perspectives.

Although it has been well researched in multiple settings and for different populations, CPS has been relatively understudied in school settings [17]. According to Greene [21], an evaluation of the local implementation of CPS in a school district in Maine, USA, reduced the number of discipline referrals, detentions, suspensions, peer aggression and acts of defiance. In a small sample (n = 10) of high school students with emotional and behavioural difficulties, Rock [22] found no effect on intrinsic motivation (as measured by the self-determination questionnaire) of implementing a “CPS strategy”, although the participating teachers and mental health professionals stated that it could be a beneficial initiative if the appropriate structures and training were in place. Rock [22] discusses the methodological limitations of the study design with regard to staff training in the CPS model and records data on its implementation. Thus, there is a need for further research on the CPS model in a school context to better understand under which circumstances CPS can have a positive effect on student outcomes.

1.2. Understanding the Complexity of CPS Intervention with Regard to Participants and Settings

In this study, when investigating the effect of CPS on student outcomes, three specific aspects were considered. First, the intention was to take into account the complexity of and variability in students’ needs with regard to the unique needs of students with behavioural problems, as there is a complex interplay of factors that cause disruptive behaviours [3]. Tincani and Travers [23] call for a description of the specific conditions under which an intervention is implemented to gain a deeper understanding of the boundaries of an intervention in order to understand for whom and under which conditions an intervention is effective. It is important to identify potential confounding factors pertaining to specific contexts or the unique needs of students [24]. If the effect of an intervention has not been established, this may be because it was not implemented with fidelity, but it may also depend on unique characteristics of the student or specific circumstances in the school context. For example, in a study by Wood et al. [25], which plotted the outcomes of an intervention together with teacher implementation, the researchers found that despite the overall lack of effect, the level of students’ on-task behaviour only increased on specific occasions when the intervention was consistently implemented. The current study specifically focuses on students’ unique situations, plotting intervention phases and extraneous events alongside the outcome measures. In addition, to further address issues of social validity, this study not only uses the systematic direct observations of students’ behaviour, but also teachers’ ratings of students’ behaviour. Previous studies have shown that teachers’ direct ratings of their students’ behaviour are valid and sensitive measures when they are used to evaluate classroom interventions and are concordant with researchers’ systematic observations [26,27].

Second, this study particularly focused on the social validity, acceptability and usability of the CPS intervention. Although social validity is pertinent to the evaluation of interventions for students with behavioural problems [28], it remains an understudied construct in single-case research [29]. Social validity pertains to the importance of goals, the extent to which intervention procedures are accepted by the participants and the effectiveness of intervention outcomes for the users and receivers of an intervention. Social validity is closely associated with the extent to which a particular intervention is implemented and integrated into practice [29,30]. Briesch et al. [31,32] further expanded the investigation of social validity and introduced the concept of usability, including multiple factors at different levels pertaining to the use of an intervention: individual factors, factors relating to the specific intervention and contextual factors. This study uses Briesch and colleagues’ operationalisation of usability [31,32] in order to gain a deeper understanding of the prerequisites of the usability of the CPS intervention in school contexts.

1.3. The Characteristics of Alternative Educational Settings for Children with Behavioural Problems

This study evaluates the use of the CPS intervention in an alternative school setting. In Sweden, students in need of special support can receive education in an alternative educational placement if they are regarded as being in need of such support [33]. As of 2021/2022, there were 13,400 pupils (1.2% of all students in compulsory school) [34] enrolled in alternative educational settings. These settings are characterised by a low student-to-teacher ratio and considerable knowledge and expertise among professionals, which enables them to meet the complex needs of students with behavioural problems [35]. However, these settings have also been criticised as stigmatising and providing low-quality education [36]. Reports about the benefits and challenges of alternative settings have been echoed in international studies. While these settings have small class sizes, extended curricula involving behavioural support and a belief that all students can succeed, they are traditionally associated with stigma and have “a negative connotation” [37]. Teachers in such settings experience insufficient planning time, are concerned about not being able to meet all their students’ needs and perceive a discrepancy between the ideal and the actual daily work [38,39]. Studies have also reported high teacher attrition and burnout rates [40]. McDaniel et al. [37] point to the need for studies in which behavioural interventions are adapted to the complex requirements of alternative settings.

To summarise, previous research has outlined challenges in the provision of support to children with behavioural problems and the need for innovative interventions. The CPS intervention has proved to be effective in therapeutic facilities, but the effects of this intervention in school settings has not been studied to the same extent. This study intends to contribute to previous research by applying the CPS intervention in alternative school settings, which may pose specific challenges to the usability of the intervention. The aim of this study is to evaluate the Collaborative and Proactive Solutions model (CPS) for students with behavioural problems in an alternative educational setting. This study poses the following three research questions.

- (a)

- How does the CPS intervention function for specific students in their specific contexts?

- (b)

- Is CPS effective in reducing students’ off-task behaviour?

- (c)

- What are teachers’ and students’ perceptions of the usability of the CPS intervention?

2. Materials and Methods

The effect of the CPS intervention on children’s off-task behaviour was evaluated using a single-subject experimental design in which the off-task behaviour of two students was monitored using the researchers’ systematic direct observations and the teachers’ direct behaviour ratings. Single-subject design is applicable in special needs education in alternative settings, as it takes into account individual student development in context and provides a degree of experimental control beyond the case study method [41]. Prior to the start, this study was reviewed by National Ethical Board (dnr 2021-01524). Informed consent was retrieved from students’ parents and teacher assistant using both written information as well as answering any questions they had directly. Students were informed in a child-friendly way both in writing and directly about this study. Students’ informal consent to participate in observations and interviews was negotiated and renegotiated throughout this study. A critical aspect of the CPS intervention is that the student is repeatedly informed that the participation is voluntary and that any solutions implemented must be mutually satisfactory. Students’ and teacher assistants’ names or other information that could be directly linked to the specific participants were excluded in the data collection and analyses. Pseudonyms were used for the participating students.

2.1. Participants and Setting

In order to be included in this study, the participants needed to be considered by a classroom teacher as (a) showing disruptive behaviour in the classroom and (b) being able to engage in a conversation with an adult for at least 10 min, and (c) the students should have been placed in an alternative educational setting for at least two months and (d) should not be the target of any other major psychosocial treatment or assessment in or outside of school during baseline or intervention conditions. Initially, the intention was to recruit four students. However, due to unexpected sick leave on the part of the participating teacher, only two students and one teacher assistant were recruited.

The two students, Bill and Sam, were placed in an alternative educational setting that included eight students in years one to five. Both students were eligible for special support and were temporarily placed in an alternative educational setting as part of their individual education plan (IEP) at their regular schools. The pupils were placed in this setting after the head teacher and the healthcare team at their regular school had decided that the adaptations and special support provided by the school were not sufficient for the students to develop in accordance with the knowledge requirements for one or more subjects. A contributing factor in most of these kinds of placement decisions was that the students had exhibited disruptive behaviour that was considered too difficult for the school staff to manage. Placement in an alternative educational setting may last for one school year or may be a permanent placement for the entire duration of compulsory education (Swedish Educational Agency, 2014).

Bill was an 8-year-old boy in second year, diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In his IEP, Bill was described by his teachers as hyperactive, impulsive, exhibiting a very limited ability to concentrate on his schoolwork and thus failing to complete his assignments, and often leaving the classroom. Further, it was documented that Bill was often observed using condescending language towards his peers, which often led to conflicts that required help from the school staff. The primary measure in Bill’s IEP was his placement in a special teaching group in an alternative educational setting. The IEP described Bill as being in need of constant support from adults during lessons, breaks and lunch time. During the ALSUP (Assessment of Lagging Skills and Unresolved Problems), 15 unsolved problems were identified. Examples of unsolved problems included difficulty remaining seated during Swedish lessons, difficulty remaining in the classroom during film presentations in natural science lessons, difficulty writing answers without assistance on maths worksheets and difficulty writing above line in Swedish literacy book.

Sam was a 10-year-old boy in fourth year. A few months before the intervention, he was evaluated at a psychiatric outpatient clinic and was described as exhibiting cognitive and social functioning consistent with neurodevelopmental disorders. However, it was not possible to establish a diagnosis at the time, due to an instability of home and school arrangements. In his IEP, Sam was described by his teachers as being hyperactive, impulsive and “lacking boundaries” in his behaviour in relation to adults and peers and was often not present in the classroom when lessons began. Like the other student, Sam’s main intervention in his IEP consisted of his placement in a special teaching group in a restricted educational setting. Furthermore, Bill’s IEP stated that he needed support in most of his interactions with adults and peers. During the ALSUP assessment, 18 unsolved problems were identified. Examples of the identified unsolved problems included difficulty finishing assignments related to time in maths, difficulty staying quiet during social science lessons and difficulty remaining seated at the start of a maths lesson.

2.2. Dependent Variable and Data Collection

The primary dependent variable was the percentage of observation intervals with off-task behaviour measured using systematic direct observation (SDO). To enhance the reliability and validity of SDO procedures, the behaviours and systematic procedures for observation were defined prior to this study [42,43]. Off-task behaviour was defined as talking about topics that were irrelevant to the lesson content, commenting on the behaviour of others, using mobile devices during lessons, shouting out or sighing loudly, leaving his seat without permission, leaving the classroom without permission, playing with lesson materials in inappropriate ways. The primary dependent variable was measured using 10 s partial interval recording for 10 min data collection sessions three to six times per week.

The secondary dependent variable was the percentage of the 10 min data collection session (same as the primary dependent variable) during which the student exhibited off-task behaviour, measured by a direct behaviour rating (DBR) made by the teachers. Off-task behaviour was defined in the same way as the primary dependent variable. The scale was 0 to 100 percent with 10-point steps. Directly after the end of a lesson that had included a data collection session, the observers prompted the teacher who was responsible for the current lesson to rate the off-task behaviour on a form. A total of five teachers and teacher assistants submitted ratings.

Two master’s students in psychology conducted the data collection for the primary dependent variable. They had been trained in the direct observation procedure directly before the baseline phase through individual instruction. Also, before the observers collected data independently, the first author co-observed and provided feedback on coding until at least 90% agreement was reached.

In accordance with recommendations for single-subject design research [44], visual analysis was used to analyse the effects of CPS. Visual analysis [44] focused on the level and trend in the observed off-task behaviours, as well as variability in both the baseline and the intervention phase. In addition, Tau-U effect sizes were calculated using an online single-case Tau-U calculator [44,45]. This nonparametric non-overlap measure offers greater power and precision than other non-overlap statistics [46]. As suggested by Vannest and Ninci [42], a resulting Tau-U score of between 0 and 0.20 indicates a small effect, 0.20 and 0.60 a moderate effect, 0.60 and 0.80 a large effect, and above 0.80 a very large effect.

2.3. Interobserver Agreement (IOA)

Interobserver agreement data were collected by two independent observers for 83% of the observation sessions for Bill (67% during the baseline and 91% during the intervention phase) and in 86% of observations for Sam (82% during the baseline and 91% during the intervention phase).

Interobserver agreement for off-task behaviour was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the total number of intervals and then multiplying the result by 100 [45]. During the baseline, the IOA for off-task behaviour was 92% (range = 80–98%) for Bill and 92% (range = 78–100%) for Sam. During the intervention, the IOA for off-task behaviour was 92% (range = 87–95%) for Bill and 96% (range = 72–100%) for Sam.

2.4. Experimental Design

A single-subject multiple baseline design for all students was applied to investigate whether there was a functional relationship between the CPS intervention and students’ off-task behaviour [44]. This design was chosen because the intervention effects were unlikely to reverse following training and coaching. The intention was for the first participant, Bill, to be moved from baseline to intervention when a minimum of five consecutive data points demonstrated a stable, non-therapeutic trend. However, due to time constraints, a decision was taken to start with the intervention when the minimum requirement of five data points was achieved. For the second student, Sam, the intention was to implement the intervention after a therapeutic increase in level and/or trend across at least three consecutive data points could be demonstrated for Bill, the first student. However, due to illness and time constraints, the intervention was introduced to Sam after five weeks, before any effect was noted for the first student, Bill. The primary dependent variable was observations of students’ off-task behaviour. The data collection procedures were constant during all the phases of this study and classroom instruction followed the regular curriculum.

2.4.1. Training

All training in the CPS model was conducted before implementation of the intervention, spread over a period of one school year, and was led and supervised by the first author, who is also a certified provider of the CPS model.

Training for the teacher assistant responsible for the problem-solving conversations included a two-hour introductory lecture on CPS and 18 bi-weekly one-hour supervision meetings in a small group comprising four participants, including feedback on and direct instruction in all the steps of the CPS model. In accordance with evidence-based approaches to staff training [47], the training was discontinued when each staff member was considered to exhibit sufficient skills in all the steps of the model.

During the course of this study, if the supervisor of the problem-solving conversations observed deviations from any part of the CPS model, appropriate feedback was given so the staff could rectify this in relation to the upcoming problem-solving conversations.

2.4.2. Baseline

During the baseline condition, the teachers were instructed to provide instruction and support to the participating students in the same way as they had done prior to this study. The students would typically follow the daily classroom schedule and participate in lessons as usual. The observers kept their distance from the students and collected data on their off-task behaviour. The observers did not engage with the participants or their peers during the baseline condition unless the students approached them.

2.4.3. Intervention

The intervention was conducted in accordance with the CPS model [18] and included three steps: (a) individual assessment of each student using the Assessment of Lagging Skills and Unsolved Problems (ALSUP) discussion guide, including prioritising unsolved problems as the main focus in problem-solving conversations; (b) conducting problem-solving conversations (Plan B); and (c) implementing the solutions agreed upon in the problem-solving conversations.

Step (a) of the intervention was conducted in the form of meetings led by the first author, with all of the school staff (6–7 persons) participating. The ALSUP is conducted in two steps. The first step involves identifying pre-typed lagging skills on the ALSUP, with the sole purpose of helping staff view the child through a more actionable lens according to the “kids do well if they can” perspective. An example of a lagging skill is “difficulty maintaining focus”. In the second step of the assessment, the staff collaborate in writing unsolved problems that correspond to a child’s difficulty in meeting the staff’s specific expectations. An example of an unsolved problem is “difficulty finishing a maths fractions sheet”.

The wording of the unsolved problem on the ALSUP is then directly translated into the words the adult tells the student at the very beginning of the problem-solving conversation. The wording of the unsolved problem is governed by guidelines for the problem-solving process in order to be collaborative, informative and effective. The unsolved problem should not make any reference to behaviour, nor should it include adult theories on the reasons for the problem. Furthermore, it should be specific with regard to the description of the problem and the circumstances under which it occurs. An example of an unsolved problem that does not follow the guidelines is “often screams in the classroom”. The prioritisation of unsolved problems was conducted in relation to the problems that involved unsafe behaviour, occurred most frequently or had a negative impact on the students or others.

Step (b): The problem-solving conversations constituted Plan B in the CPS model. According to Greene [18], any unsolved problem can be approached using one of three plans: Plan A (unilateral problem solving without involving the child), Plan B (collaborative problem solving) and Plan C (putting the problem aside for a period of time). During the intervention, a preliminary plan was made regarding the number of problems that could be the focus of the intervention (Plan B), and which problems would be managed using Plan C. Only fidelity to the implementation of Plan B and the solutions generated from these problem-solving conversations were measured.

In Plan B, the aim of the problem-solving conversation was that the student and teacher would agree on solutions to the unsolved problems. The problem-solving conversation comprises three steps: Empathy, Define Adult Concern and Invitation. In the Empathy step, the adult gathers information from the student about their concern or perspective on a given unsolved problem. In this step, the focus is especially on what it is that is making it difficult for the child to meet the specific expectation. The adult has a set of strategies at hand, including reflective listening and clarifying statements, asking for specific details regarding the unsolved problem, asking the student why the problem manifests in certain circumstances and not others, and summarising their concerns. In the Define Adult Concerns step, the adult states their concern (i.e., the consequences of the unsolved problem for the student or others). In the Invitation step, the child and adult collaborate in order to identify a realistic and mutually satisfactory solution.

In step (c), the solutions derived from the problem-solving conversation are further implemented by the teachers and the students during the CPS intervention. The solutions are continuously evaluated in subsequent problem-solving conversations.

During the problem-solving conversation process, weekly team meetings with all school staff were held on an ongoing basis in order to engage and inform them. The agenda for these meetings was to discuss specific adult expectations, decide whether the proposals for solutions that had emerged during the problem-solving conversations were realistic and satisfactory from the school’s perspective, and remind the school staff about the solutions that had been previously implemented. In the intervention, these meetings were held on a weekly basis. The observers collected data on the participants’ off-task behaviour throughout the intervention using the same methodology that was used during the baseline phase.

2.4.4. Implementation Fidelity

Problem-solving conversations. The implementation fidelity of the problem-solving conversations (step b) was measured by rating the fidelity of the video-recorded conversations, using a modified version of the Plan B meeting checklist [48]. The checklist originally included 15 items, some of which were divided in order to capture separate aspects of the conversations, resulting in 17 items in the modified version. For example, the item “The unsolved problem is split (rather than clumped) and contains no adult theories, no challenging behaviours, and is as specific as possible” [48] was divided into four different items to be individually rated. Each of the 17 items in the revised Plan B meeting checklist scored either 0 (meaning not displaying sufficient proficiency), 1 (displaying partially sufficient proficiency) or 2 (displaying sufficient proficiency). The total score would have to be at least 25 (74%) out of 34 possible points in the checklist to be regarded as meeting a good enough standard for a Plan B conversation (Appendix A Table A1). All of the problem-solving conversations included in this study were video-recorded and rated by two observers, who were both experienced and certified providers of the CPS model. One rating was given to all conversations related to each unsolved problem, even though they took place on multiple occasions. The IOA between the observers for the problem-solving conversation rating for both Bill and Sam was 88%. In the fidelity rating for the video-recorded problem-solving conversations, the observers also noted the exact wording of the unsolved problems, the concerns of students and adults, as well as the solutions to be used.

Implementation of the solutions (step c). Ratings of the extent to which the solutions in the problem-solving conversations were implemented were obtained by the observers directly after each session. The solutions were rated according to whether they were “always”, “sometimes” or “never” implemented during the sessions, with the “not applicable” option being available. The IOA for the solutions was 100% between the two observers for all of the sessions when there was a solution.

2.4.5. Social Validity and Usability

The students’ and the teacher assistant’s perceptions of the usability of the CPS intervention were evaluated using quantitative and qualitative methods. The participating students were interviewed by the first author using the Children’s Usage Rating Profile—Actual; CURP-A [48]. CURP-A comprises 21 items measuring three interconnected aspects of students’ perception of an intervention: personal desirability, feasibility and understanding. A high score for the personal desirability scale indicates that the participant personally likes the intervention and would be willing to participate in it. The feasibility subscale is inverted, meaning that a high score for it indicates that the participant finds the intervention too laborious or intrusive to be carried out. A high score on the understanding subscale indicates that the participant understands why the intervention is being implemented and feels confident about carrying it out in an appropriate manner [30]. The response options for all the items varied between 1 (I totally disagree) and 5 (I totally agree) but were modified to range between 1 (totally disagree) and 4 (totally agree) to adapt the instrument to the students’ needs. The items were also changed from a general formulation that would suit any intervention, to being more specific and stating that CPS was the intervention method being used. Two items from the original rating scale [30], which asked whether the student could use the method, were slightly altered to emphasise that the intervention was used by both adults and students, to better reflect the usage of the CPS model.

The teacher assistant completed the Usage Rating Profile-Intervention Revised (URP-IR) [49] and the Usage Rating Profile-Assessment (URP-A) [50]. Both instruments are psychometrically sound measures [51] designed to evaluate factors related to intervention usage [31]. The items in both URP-A (28 items) and URP-IR (29 items) refer to six subscales: acceptability, understanding, feasibility, family–school collaboration, system climate and system support. The acceptability subscale examined how acceptable the participant found the intervention/assessment. A high score for the understanding subscale indicated that the respondent was fully knowledgeable about the intervention and assessment procedures, respectively, as well as their implementation. The family–school Collaboration subscale reflected the extent to which the participant believed that family collaboration was necessary for the successful use of either the assessment or the intervention. The feasibility subscale assessed the extent to which the participant felt that it was possible to implement the assessment or the intervention with integrity, given the existing demands. The system climate subscale addressed the extent to which the intervention matched the socio-political climate of the school. The last subscale, system support, assessed the participants’ views as to whether assistance from other adults would be needed in order to use the assessment or the intervention successfully. The response options for the items in both URP-IR and URP-A vary between 1 (totally disagree) and 6 (totally agree). After the teacher assistant had completed the URP-IR and URP-A, a follow-up interview was conducted in which the teacher assistant was offered the opportunity to comment on the responses with regard to the six subscales. The interview was transcribed verbatim and analysed using manifest content analysis [52].

3. Results

The results of the single-subject experimental study are presented below with regard to the primary and secondary outcomes. In order to render a more complete understanding of the context in which the changes in students’ off-task behaviour occurred, each student’s functioning is described separately and includes a description of the problem-solving conversations and the agreed-upon solutions. Finally, the results concerning the acceptability and usability of the intervention from the student and teacher perspective are reported.

3.1. How Did the CPS Intervention Function for Bill in His School Context?

During the intervention, Bill and the teacher assistant had problem-solving conversations on seven different occasions with a mean length of 25 min (12–43 min). On these occasions, they discussed and solved two unsolved problems; the first problem was solved on three separate occasions and the second problem was solved on four separate occasions. The implementation fidelity for problem-solving conversations with Bill was rated high: 91% for both conversations.

Bill’s Problem-Solving Process

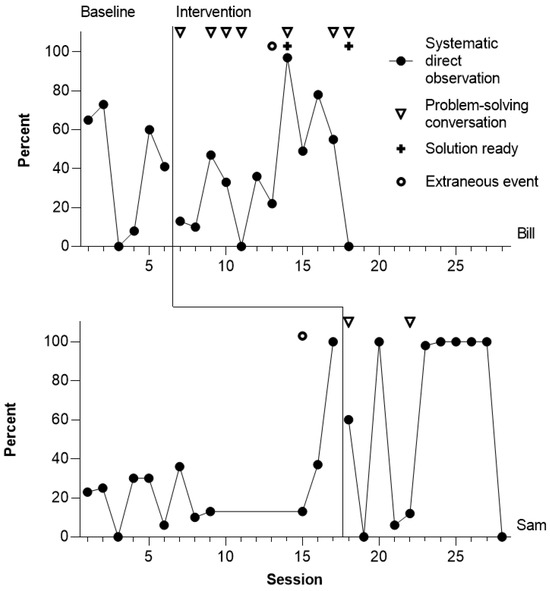

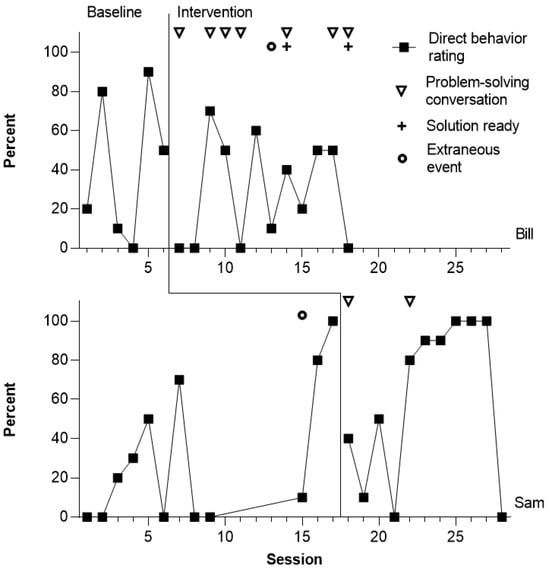

The first unsolved problem was “difficulty remaining seated during Swedish lessons”. Bill’s prioritised concern connected to this unsolved problem was that “it’s boring to just sit still in class” and the adult´s prioritised concern was that he “misses out on practicing his writing when he doesn’t hear the teacher”. The agreed-upon solution to this unsolved problem, regarded as mutually satisfactory and realistic by both Bill and the adult, was that he could sit on a specially designed wiggly chair at the back of the classroom during Swedish lessons. This solution was ready to be implemented in session 14 (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). However, from this session and onwards to the end of the intervention, the fidelity of the agreed-upon solution was rated as “never implemented” by the observers. Between sessions 13 and 14, Bill’s parents informed him that his placement in the alternative educational facility would be extended (extraneous event in Figure 1 and Figure 2). According to the teachers, this resulted in Bill finding it more difficult to participate in lessons, which may have contributed to the increased level of off-task behaviour.

Figure 1.

Percentage of observed intervals with off-task behaviour measured using systematic direct observation for each session in baseline and intervention conditions for both students.

Figure 2.

Percentage of time of off-task behaviour measured by teachers’ direct behaviour rating observations for each session in baseline and intervention conditions for both students. As seen in the figure, teacher DBRs were largely concordant with the SDOs, similar to Figure 1.

The second unsolved problem was similar to the first: “difficulty remaining seated when watching films during social science classes”. Bill’s prioritised concern was that it was difficult to be seated close to a particular student because of some personal attributes of that student, and the adult´s concern was that “other students were disturbed when Bill changed seats during the film”. The agreed-upon solution for this unsolved problem was that Bill could also sit on a wiggly chair at the back of the classroom during films in social science classes. This solution was agreed upon by session 18 (see Figure 1 and Figure 2), but the intervention was terminated due to the student being ill before it could be implemented. Because of the prematurely terminated intervention, it was not possible to address as many unsolved problems as planned in the problem-solving conversations with Bill.

3.2. Did CPS Reduce Bill’s Off-Task Behaviour?

As shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, during the baseline condition, off-task behaviour measured during the observations was at a moderate level with a slight downward trend but was highly variable for Bill (SDO mean 41%, 0–73%). When the intervention was introduced in session 7, off-task observations were initially at a lower level with less variability and a slight downward trend, but increased from session 14, resulting in a moderate level, high variability and upward trend when analysing the whole phase (SDO mean 37%, 0–97%). Analysis using the Tau-U calculator yielded a Tau-U score of −0.111, with a Z-score of −0.374 and a p-value of 0.707, thereby indicating a small non-significant effect as Bill’s off-task behaviour decreased. For direct behaviour ratings, Bill’s off-task behaviour was at a moderate level and was highly variable (DBR 42%, 0–90%) during the baseline phase. In the intervention, DBR was at a lower level, but still moderately variable compared to the baseline phase, and showed a slight downward trend (DBR mean 29%, 0–70%). Analysis using the Tau-U calculator yielded a Tau-U score of −0.236 with a Z-score of −0.796 and a p-value of 0.426, thereby indicating a moderate non-significant effect as Bill’s off-task behaviour decreased.

3.3. How Did the CPS Intervention Function for Sam in His School Context?

As seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2, Sam was absent from session 10 to session 14 of the baseline phase due to illness. Consequently, the introduction of the intervention phase was delayed by seven days and approximately four observation sessions. Thus, fewer unsolved problems could be addressed in the problem-solving conversations. When Sam returned to session 15 after his illness, he received a new mobile phone, engaging his attention and hindering his participation in the lessons (extraneous event in Figure 1 and Figure 2). During the intervention, Sam and the teacher assistant had problem-solving conversations about one unsolved problem on two separate occasions that lasted 17 min each. The implementation fidelity for the problem-solving conversations with Sam was high: 82% for the conversation conducted (split into multiple occasions).

Sam’s Problem-Solving Process

The unsolved problem was “difficulty sitting down on the chair when the maths lesson starts”. Sam’s prioritised concern regarding the unsolved problem was that it was “hard to stop playing on his mobile phone when the break between lessons was over”, and the prioritised concern of the adult was that Sam “would not be able to learn ten transitions”. Due to staff shortages related to sick leave, the intervention for both students ended early. Consequently, there was no time to discuss a solution for Sam’s unsolved problem.

3.4. Did CPS Decrease Sam’s Off-Task Behaviour?

As seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2, during the baseline condition, off-task behaviour measured by observations was at a stable low level and the variability during most of the phase only spiked in the last observation of Sam (SDO mean 26%, range 0–100) related to the extraneous event discussed above. When the intervention was introduced in session 18, Sam’s off-task behaviour was initially highly variable with no visible trend. The intervention ended with a very high level of off-task behaviour in session 23 (SDO mean 61%, range 0–100%). Analysis using the Tau-U calculator demonstrated a Tau-U value of 0.287, with a Z-score of 1.169 and a p-value of 0.242, indicating a moderate but non-significant effect, as Sam’s off-task behaviour increased. As for direct behaviour ratings in the baseline phase, teacher ratings for Sam were at a low to moderate level with an upward trend (DBR mean 29%, range 0–100%). In the intervention, DBR was at a higher level compared to the baseline phase with high variability and an upward trend (DBR mean 60%, range 0–70%). Analysis using the Tau-U calculator yielded a Tau-U value of 0.424, with a Z-value of 1.723 and a p-value of 0.084, indicating a moderate but non-significant effect, as Sam’s off-task behaviour increased.

3.5. What Are the Perceptions of Students and Teachers of the Usability of the CPS Intervention?

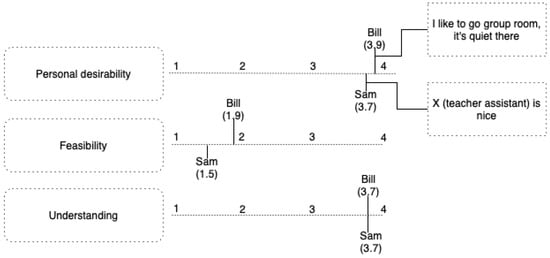

Figure 3 shows the mean score for each of the three factors of the CURP-A. Both students rated the personal desirability and understanding subscales high, indicating that they appreciated the intervention and understood why it was implemented. The results from the feasibility subscale, which was inverted, were positive for both Bill and Sam, indicating that they largely viewed the CPS intervention as feasible.

Figure 3.

Students’ ratings and comments on the usability of the CPS intervention (produced through the web-based application draw.io at www.diagrams.net (accessed on 28 August 2023).

The interviews with the students revealed that they appreciated sitting in a quiet group room during problem-solving conversations (e.g., “It’s quiet there”) and valued the teacher assistant who was responsible for the intervention (e.g., “She is nice”).

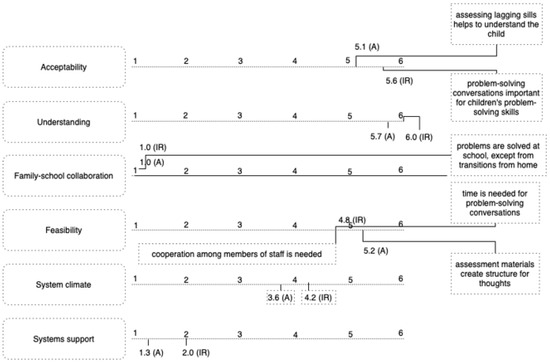

Figure 4 shows the teacher assistant’s ratings of the usability of the CPS intervention with the mean score for each of the six factors of the URP-IR and URP-A scales. The results of the acceptability, understanding and feasibility subscales were high, indicating that the teacher assistant considered herself highly knowledgeable about the intervention and assessment procedures and perceived them as possible to implement given the existing demands. The teacher assistant stated that the ALSUP often contributed to better understanding and empathy for a student among teachers, e.g., “It is sometimes the case that after ALSUP meetings, some teachers feel ashamed about talking negatively about a student’s behaviour; you can feel empathy in the air”. According to the teacher assistant, problem-solving conversations were valuable in supporting the problem-solving skills of students, e.g., “the great advantage is that students learn to solve problems, which can be useful later in adult life”.

Figure 4.

Teacher assistant’s ratings and comments on the usability of the CPS intervention (produced through the web-based application draw.io at www.diagrams.net (accessed on 28 August 2023).

Concerning the feasibility of the CPS intervention, the teacher assistant highlighted the importance of allocating time to problem-solving conversations, e.g., “it’s difficult to leave a lesson for a problem-solving conversation if you know your colleagues are sick and there is no one to substitute for them”. The teacher assistant also commented on the importance of cooperation among members of the school staff concerning common expectations of the students’ behaviour and in implementing solutions from problem-solving conversations, for example, “you can’t work alone in the team, you have to inform all the teachers about the solution that you reached with the student”.

Family–school collaboration was viewed as being necessary only to a very limited extent for both assessment and intervention. The teacher assistant stated that problems were often solved at school, except for problems in the transition from home, e.g., “it’s good to collaborate about problems related to student life at home, as eating breakfast or transition to school”. Ratings of the system climate and system support subscales indicated that the teacher assistant believed that the intervention and assessment would be quite well received within the school’s socio-political climate and that assistance from other adults was only needed to a limited extent in order to use CPS intervention correctly.

4. Discussion

This study was conducted based on the need to address the challenges in school support for students with behavioural problems and a need to develop innovative intervention approaches in order to tackle the “complex nature” of students’ problems and needs [3,14]. Previous studies indicate that students with behavioural problems experienced a lack of support, negative attitudes and poor relationships with teachers [5,8,9]. The focus of this study was on the CPS intervention approach, in which students are involved in problem solving while attention is focused on altering adults’ perceptions of problem behaviours and promoting positive relationships [17].

4.1. The Effect of CPS on Students’ Off-Task Behaviour

CPS has been evaluated in numerous studies and settings [17], but only a few studies in school settings have been conducted, and these studies have had some methodological weaknesses. The results from the present study show that the CPS intervention did not have a significant effect on the students’ off-task behaviour evaluated through systematic direct observation (primary dependent variable), as evaluated by both visual analysis and quantitative measures (Tau-U). Regarding direct behaviour ratings (DBRs) of students’ off-task behaviour, quantitative analyses revealed no significant effect, but visual analyses showed that, for Bill, there was a lower level of off-task behaviour in the intervention phase compared to the baseline phase, and a slight downward trend was observed in off-task behaviour. No effect was observed for Sam after two problem-solving conversations. Thus, the results are not in line with previous research on the effectiveness of the CPS intervention, as evaluated in therapeutic facilities, families and schools [17]. However, due to the fact that the design could not support the functional relationship between the intervention and results, and due to a lack of implementation fidelity in parts of the intervention, it is not possible to draw any conclusion of the effectiveness of the CPS intervention in an alternative school setting. Nevertheless, the results from this study can be used to plan future evaluations of the CPS intervention in school settings.

First, it is important to take into account the fidelity of implementation of the CPS intervention. The problem-solving conversations (step b) met the requirements of an acceptable level of implementation of the CPS intervention. However, the implementation of the solutions (step c) did not reach an acceptable level, as none of the two solutions for Bill were implemented with integrity. Thus, as highlighted in intervention research in general [23,24], the implementation fidelity of the agreed-upon solutions might have contributed to the null effects in this study. Previous research has revealed high levels of teacher attrition and burnout in alternative settings [40]. The teachers in such settings may experience insufficient time for planning and may be concerned about not meeting their students’ needs [38,39]. In our study, the problem-solving conversations involving Sam could not be conducted as planned, due to a teacher being away on sick leave. Also, the interview with the teacher assistant revealed a need for cooperation among teachers in implementing solutions within the CPS intervention. Thus, if a CPS intervention is to be implemented with fidelity in alternative school settings, a stable and supportive environment must be in place that provides the necessary resources in terms of time and personnel.

Second, the extraneous events that occurred during the intervention phase for Bill and during the baseline phase for Sam may have contributed to their off-task behaviours beyond the intervention, per se. As seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2, during intervention sessions 13 and 14, Bill was told that he would remain in the alternative setting. This made him upset and may have led to an increase in his off-task behaviour, according to the teachers. Although alternative settings have more resources than mainstream settings to provide support to students with behavioural problems, these settings are often associated with stigma and have “negative connotations” [36,37], which may have been the issue in Bill’s case. Sam received a new smartphone during session 15 of the baseline phase, which made it difficult for him to stop playing games when lessons started. There may be a complex interaction between multiple factors that contribute to disruptive behaviours [3]. These factors are difficult to predict, but they may need to be taken into account when planning and evaluating CPS interventions.

4.2. Teachers’ and Students’ Perceptions of the Usability of the CPS Intervention

This study focused on studying the usability of CPS interventions from the perspective of the participating students and the teacher assistant. Social validity is an important construct that may determine whether an intervention is implemented and sustained in a particular context [27,28]. In this study, the evaluation of social validity was extended to include multiple factors that may be of significance to the usability of interventions with regard to the individuals implementing the intervention, the intervention’s characteristics and the contextual factors [29,30]. The results of this study show that both teacher and students rated the acceptability and understanding of the intervention at a high level. The students were positive about being in a quiet room and expressed their liking for the teacher assistant who conducted the problem-solving conversations. The teacher assistant commented on the benefits of the CPS intervention regarding the teachers’ altered perceptions of problem behaviours as a result of the ALSUP assessment and the advantages of conversations for students’ problem-solving skills. Thus, based on this small-scale study, it could be concluded that both students and teachers view the procedures and goals of the CPS intervention as socially valid (cf., Ref. [29]). Concerning the feasibility and system climate for the CPS intervention, these dimensions received lower ratings from the teacher assistant, especially with regard to the problem-solving conversations (part b of the CPS intervention) and the implementation of the solutions (part c of the CPS intervention). The teacher assistant commented on the need for sufficient time when conducting problem-solving conversations, as well as the need for cooperation in establishing common expectations of students’ behaviours and implementing the agreed-upon solutions. Thus, the results suggest that if a CPS intervention is to be sustained and continuously implemented in an alternative setting, organisational structures need to be in place in order to facilitate the implementation.

4.3. Study Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution due to a number of limitations. First, despite the ambition to use a multiple-baseline single-subject design, which accounts for the timing of treatment effects, due to illness among personnel and time constraints, an AB design was used in which the baseline assessment was followed by an intervention for the second student, without first achieving an effect for the first student. This type of design has limitations in terms of the opportunities to establish experimental control [44], as the design of this study failed to demonstrate three instances of a functional relationship between the intervention and the dependent variables. Second, due to time constraints, the number of problem-solving conversations for both students did not reach the dosage reported in previous studies (e.g., Ref. [19]). Third, the conclusions of the usability of the intervention are based on three participants and this limits the generalisation of the results beyond the students and the teacher assistant who participated in this study.

4.4. Conclusions

Despite this study’s limitations, it may have important contributions to previous research on interventions for children with behavioural problems. This study does not confirm previous findings on the effectiveness of CPS, as conducted in therapeutic facilities, families and schools [17]. Possible explanations to the null effects are the dosage of the CPS intervention used in this study and challenges to the implementation of the CPS intervention in alternative settings. For example, the results suggest that although the students and the teacher assistant viewed the CPS intervention as acceptable, they expressed the need to organise support structures and procedures for the implementation of CPS interventions in terms of the amount of time allocated to problem-solving conversations and procedures for cooperation among school staff members. With regard to previous research on the specific demands of alternative settings [37,38,39,40], future studies might need to take into account the organisation and support structures in place to enhance implementation of the CPS intervention.

Author Contributions

S.B. was responsible for methodology, data curation, funding acquisition and writing. M.K. was responsible for conceptualization and formal analysis. C.S. had special responsibility concerning methodology, software and supervision. N.K. was responsible for conceptualization, supervision and writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by an Uppsala Municipality School Development Grant. The APC was funded by Mälardalen University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Prior to the start of study, the study was reviewed by the National Ethical Board (dnr 2021-01524). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Swedish National Ethics Board (2021-01524) on the 19th of April 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, the anonymized data will be shared with researchers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Plan B Coding Form

Instructions:

Put a cross (X) for each point below according to your assessment of whether the skill is shown in the conversation. For the conversation as a whole to be assessed to reach the criteria for a Plan B-conversation the total score must be at least 25, 74% of 34 possible.

0: Does not show skill sufficiently in conversation,

1: In part showing sufficient skill in conversation

2: Showing sufficient skill in conversation

Table A1.

Plan B Coding Form.

Table A1.

Plan B Coding Form.

| Plan B Coding Form | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empathy Step | Rating | Comment | ||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | ||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| Define adult concerns step | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| Invitation | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| General comments: | ||||

Total score: /34 points.

References

- Reid, R.; Gonzalez, J.E.; Nordness, P.D.; Trout, A.; Epstein, M.H. A Meta-Analysis of the Academic Status of Students with Emotional/Behavioral Disturbance. J. Spec. Educ. 2004, 38, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K.R.; Gonzales, C.R.; Reinke, W.M. Empirically Derived Subclasses of Academic Skill among Children at Risk for Behavior Problems and Association with Distal Academic Outcomes. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2019, 27, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, T.W.; Sutherland, K.S.; Talbott, E.; Brooks, D.S.; Norwalk, K.; Huneke, M. Special Educators as Intervention Specialists: Dynamic Systems and the Complexity of Intensifying Intervention for Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2016, 24, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehby, J.H.; Symons, F.J.; Shores, R.E. A Descriptive Analysis of Aggressive Behavior in Classrooms for Children with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. Behav. Disord. 1995, 20, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Lavoie, J. Students’ perceptions of schooling: The path to alternate education. Int. J. Child Youth Fam. Stud. 2016, 7, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T.N.; Sutherland, K.S.; Lotze, G.M.; Helms, S.W.; Wright, S.A.; Ulmer, L.J. Problem Situations Experienced by Urban Middle School Students with High Incidence Disabilities That Impact Emotional and Behavioral Adjustment. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2015, 23, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewe, L. ADHD symptoms and the teacher-student relationship: A systematic literature review. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 2019, 24, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, D.L.; Koomen, H.M. Student–Teacher Relationships and Students’ Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors: A Cross-Lagged Study in Secondary Education. Child Dev. 2021, 92, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, G.; McEnteggart, C.; Barnes-Holmes, Y. Attitudes to pupils with EBD: An implicit approach. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 2020, 25, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, R.R.; de Boer, A.; Minnaert, A. What do Dutch general education teachers do to facilitate the social participation of students with SEBD? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garwood, J.D.; Peltier, C.; Sinclair, T.; Eisel, H.; McKenna, J.W.; Vannest, K.J. A Quantitative Synthesis of Intervention Research Published in Flagship EBD Journals: 2010 to 2019. Behav. Disord. 2021, 47, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, B.S.; Hatton, H.; Lewis, T.J. An Examination of the Evidence-Base of School-Wide Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports Through Two Quality Appraisal Processes. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2018, 20, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmann, M.; Seeliger, G.M. SEBD inclusion research synthesis: A content analysis of research themes and methods in empirical studies published in the journal Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties from 1996–2014. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 2017, 22, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggin, D.M.; Cook, B.G. Behavioral Disorders: Looking Toward the Future With an Eye on the Past. Behav. Disord. 2017, 42, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, A.L.; McDaniel, S.C.; Fernando, J.; Troughton, L. Goal-Setting Interventions for Students with Behavior Problems: A Systematic Review. Behav. Disord. 2016, 41, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E.W.; Lane, K.L.; Crnobori, M.; Bruhn, A.L.; Oakes, W.P. Self-Determination Interventions for Students with and at Risk for Emotional and Behavioral Disorders: Mapping the Knowledge Base. Behav. Disord. 2011, 36, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, R.; Winkler, J. Collaborative & Proactive Solutions (CPS): A Review of Research Findings in Families, Schools, and Treatment Facilities. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 22, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Greene, R.W. Lost and Found: Helping Behaviorally Challenging Students; Jossey-Bass: San Fracisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick, T.H.; Greene, R.W.; Austin, K.E.; Fraire, M.G.; Halldorsdottir, T.; Allen, K.B.; Jarrett, M.A.; Lewis, K.M.; Whitmore Smith, M.; Cunningham, N.R.; et al. Parent Management Training and Collaborative & Proactive Solutions: A Randomized Control Trial for Oppositional Youth. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2016, 45, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Greene, R.W. The Explosive Child: A New Approach for Understanding and Parenting Easily Frustrated, Chronically Inflexible Children; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, R.W. Collaborative & Proactive Solutions: Applications in schools and juvenile detention settings. In Advances in Conceptualisation and Treatment of Youth with Oppositional Defiant Disorder: A Comparison of Two Major Therapeutic Models, Proceedings of the Eighth World Congress of Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies, Melbourne, Australia, 22–25 June 2016; Australian Academic Press: Queensland, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rock, A.J.M. A Mixed Methods Approach to Using Collaborative and Proactive Solutions with Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders While Applying the Self-Determination Theory. Paper 314. Ph.D. Thesis, St. John Fisher University, Rochester, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tincani, M.; Travers, J. Publishing Single-Case Research Design Studies That Do Not Demonstrate Experimental Control. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2018, 39, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, J.R.; Gast, D.L. Measuring procedural fidelity in behavioural research. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2014, 24, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, B.K.; Umbreit, J.; Liaupsin, C.J.; Gresham, F.M. A Treatment Integrity Analysis of Function-Based Intervention. Educ. Treat. Child. 2007, 30, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley-Tillman, T.C.; Chafouleas, S.M.; Sassu, K.A.; Chanese, J.A.M.; Glazer, A.D. Examining the Agreement of Direct Behavior Ratings and Systematic Direct Observation Data for On-Task and Disruptive Behavior. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2008, 10, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.L.; Eklund, K.; Kilgus, S.P. Concurrent Validity and Sensitivity to Change of Direct Behavior Rating Single-Item Scales (DBR-SIS) Within an Elementary Sample. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2018, 33, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spear, C.F.; Strickland-Cohen, M.K.; Romer, N.; Albin, R.W. An Examination of Social Validity Within Single-Case Research with Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2013, 34, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snodgrass, M.R.; Chung, M.Y.; Meadan, H.; Halle, J.W. Social validity in single-case research: A systematic literature review of prevalence and application. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 74, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.M. Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1978, 11, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briesch, A.M.; Chafouleas, S.M. Exploring Student Buy-In: Initial Development of an Instrument to Measure Likelihood of Children’s Intervention Usage. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 2009, 19, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briesch, A.M.; Chafouleas, S.M.; Neugebauer, S.R.; Riley-Tillman, T.C. Assessing influences on intervention implementation: Revision of the Usage Rating Profile-Intervention. J. Sch. Psychol. 2013, 51, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedish Education Act SFS 2010:800. Available online: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800 (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Swedish National Agency for Education. Statistics on Special Support in Compulsory School 2021/2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/fler-statistiknyheter/statistik/2022-04-21-statistik-om-sarskilt-stod-i-grundskolan-2021-22 (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Swedish National Agency for Education. Separate Teaching Units for Students with Behavioural Problems. A Study of the Organisation and Use of Separate Teaching Units in Primary School. [Särskilda Undervisningsgrupper. En Studie om Organisering och Användning av Särskilda Undervisningsgrupper i Grundskolan]; Report 405; Stockholm Fritzes Kundservice: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Malmqvist, J. Working successfully towards inclusion-or excluding pupils? A comparative retroductive study of three similar schools in their work with EBD. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 2016, 21, 344–360. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, S.C.; Wilkinson, S.; Simonsen, B. Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports in Alternative Educational Placements. In Advances in Learning and Behavioral Disabilities; Landrum, T.J., Cook, B.G., Tankersley, M., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bentley, UK, 2018; Volume 30, pp. 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bettini, E.; Wang, J.; Cumming, M.; Kimerling, J.; Schutz, S. Special Educators’ Experiences of Roles and Responsibilities in Self-Contained Classes for Students with Emotional/Behavioral Disorders. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2019, 40, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.M.; Brunsting, N.C.; Bettini, E.; Cumming, M.M.; Ragunathan, M.; Sutton, R. Special Educators’ Working Conditions in Self-Contained Settings for Students with Emotional or Behavioral Disorders: A Descriptive Analysis. Except. Child. 2019, 86, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, A.F.; Sandilos, L.E.; Pilny, W.V.; Schwartz, S.; Wehby, J.H. Teaching Students with Emotional/Behavioral Disorders: Teachers’ Burnout Profiles and Classroom Management. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2022, 30, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, R.H.; Carr, E.G.; Halle, J.; McGee, G.; Odom, S.; Wolery, M. The Use of Single-Subject Research to Identify Evidence-Based Practice in Special Education. Except. Child. 2005, 71, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gast, D.L. Single Subject Research Methodology in Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin, A.E. Single-Case Research Designs: Methods for Clinical and Applied Settings, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vannest, K.J.; Ninci, J. Evaluating Intervention Effects in Single-Case Research Designs. J. Couns. Dev. 2015, 93, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannest, K.J.; Parker, R.I.; Gonen, O.; Adiguzel, T. Single Case Research: Web Based Calculators for SCR Analysis; Version 2.0; [Web-Based Application]; Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.singlecaseresearch.org (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Parker, R.I.; Vannest, K.J.; Davis, J.L. Effect Size in Single-Case Research: A Review of Nine Nonoverlap Techniques. Behav. Modif. 2011, 35, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.B.; Rollyson, J.H.; Reid, D.H. Evidence-Based Staff Training: A Guide for Practitioners. Behav Anal. Pract. 2012, 5, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lives in the Balance. Plan B Checklist. Lives in the Balance. Available online: http://livesinthebalance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Plan-B-Meeting-Checklist2020.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Chafouleas, S.M.; Briesch, A.M.; Neugebauer, S.R.; Riley-Tillman, T.C. Usage Rating Profile—Intervention, revised ed.; University of Connecticut: Storrs, CT, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chafouleas, S.M.; Miller, F.G.; Briesch, A.M.; Neugebauer, S.R.; Riley-Tillman, T.C. Usage Rating Profile—Assessment; University of Connecticut: Storrs, CT, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, F.G.; Neugebauer, S.R.; Chafouleas, S.M.; Briesch, A.M.; Riley-Tillman, T.C. Examining Innovation Usage: Construct Validation of the Usage Rating Profile—Assessment. Poster Presentation at the American Psychological Association Annual Convention, Honolulu, HI, USA. 2013. Available online: https://dbr.education.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/916/2015/07/2013-APA-Miller-Neugebauer-Chafouleas-Briesch-Riley-Tillman.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Krippendorf, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; SAGE: Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).