Storytelling as a Skeleton to Design a Learning Unit: A Model for Teaching and Learning Optics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Design and Methodology

2.1. The Context

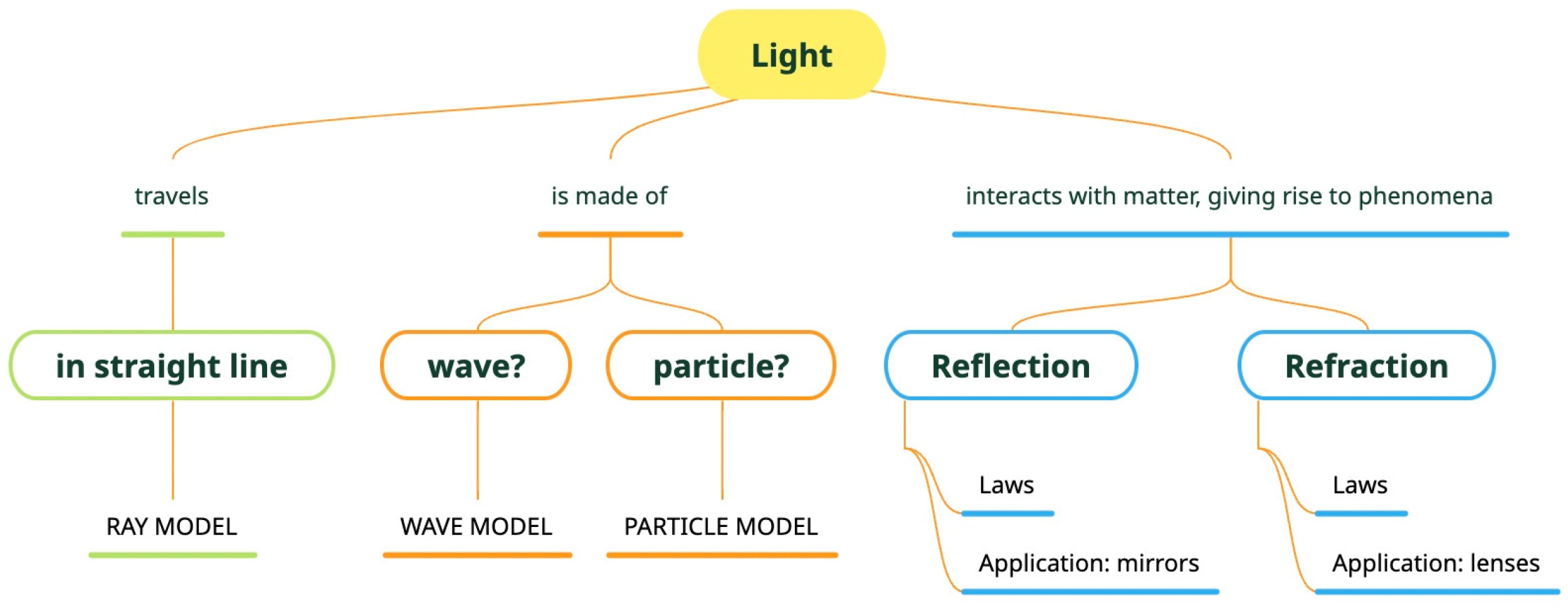

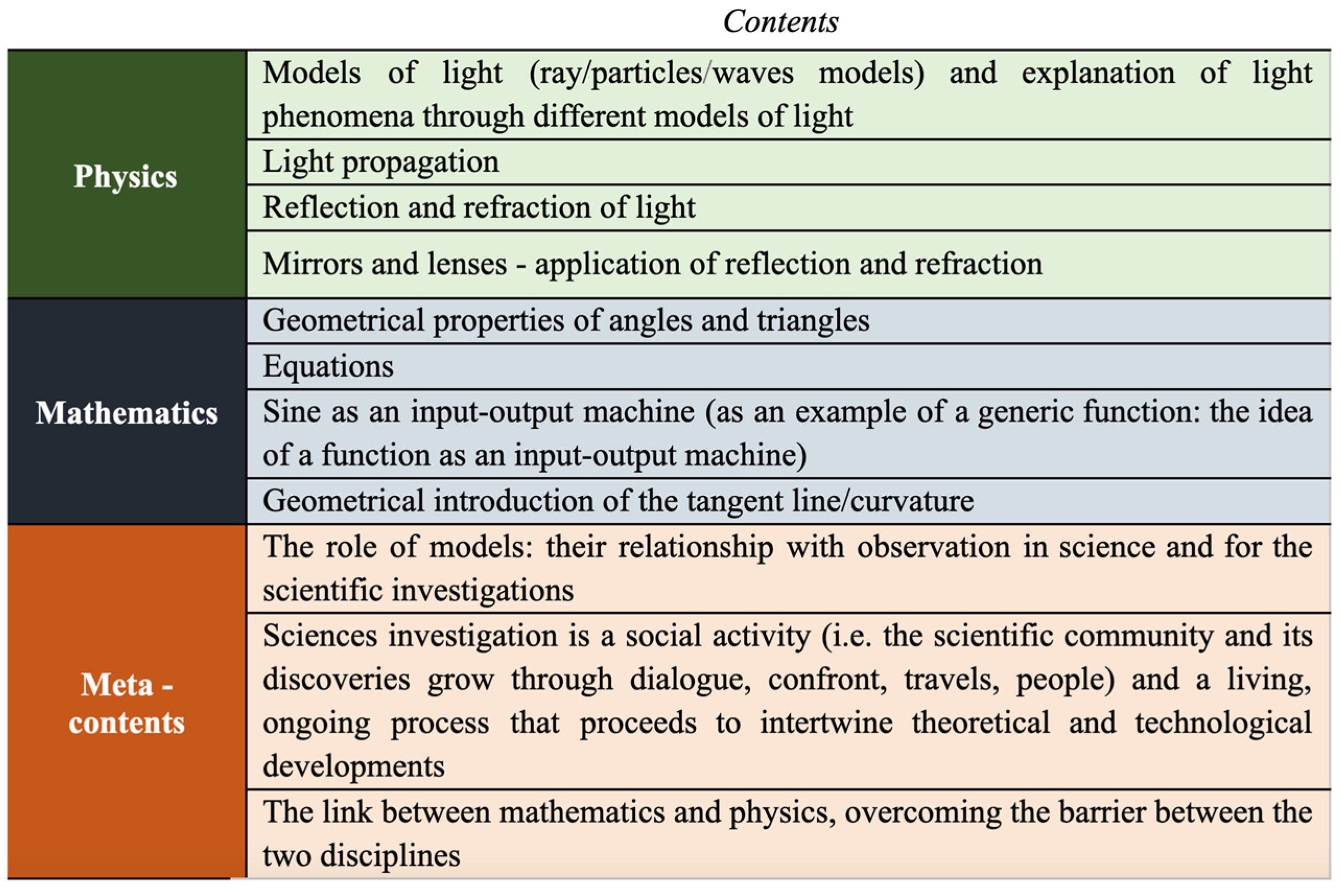

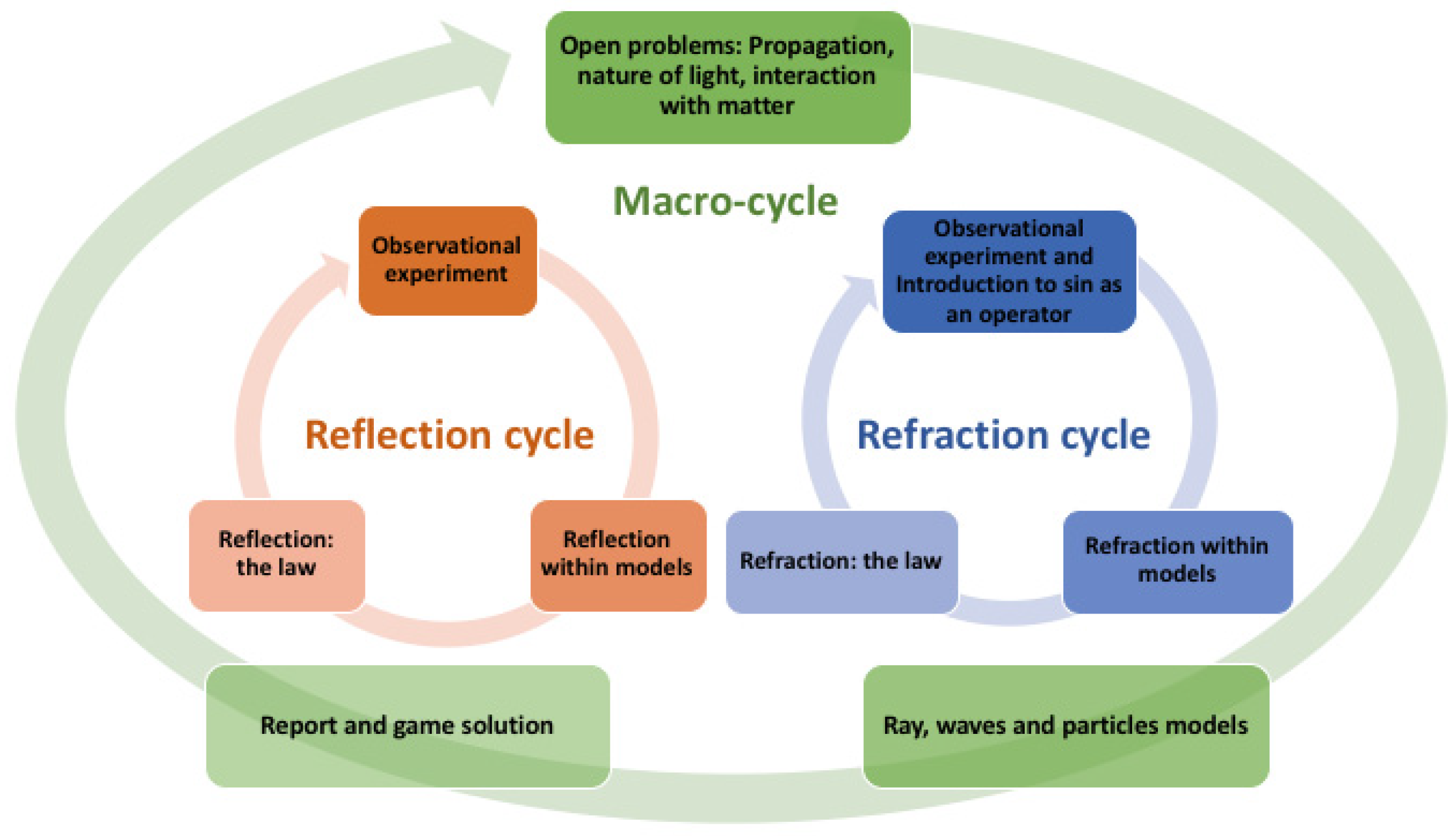

2.2. The Didactic Unit: Teaching and Learning Optics

- Enhanced argumentation and modelling skills in physics and mathematics.

- Address one of the pivotal themes of physics, light, more completely and profoundly.

- Promote a view of science as a social and living process.

- Promote self-assessment on several levels that are linked to disciplinary content, related to the collaborative dimension, as well as argumentative competence.

- Be encouraged to participate and then overcome their fear of taking action as, through storytelling and role play, they will be able to feel less judged by others and more involved.

2.2.1. Design Choices

2.2.2. The Scientific Problem

3. Results

3.1. Identikit of the Unit

3.2. The Structure of the Unit

- Exploratory stage.

- Conflict/generation/conjecture phase.

- Formalisation–demonstration.

- Modelling/application/transfer to other contexts.

- Assessment.

3.3. The Narrative Structure

“After walking all night trying to reach the company, suddenly our heroes are surrounded by hordes of orcs and the only way to escape is a door in the mountain.Fortunately, the sun is rising, a ray hits the gates, and they open!This happens only on very particular moments. Destiny? Luck? Or perhaps the powers of light... Galadriel was right.Our characters are saved from the orcs! But the dwarves, who are used to the darkness of these places, notice another danger. There are rays to defend the entrance, if they interrupt the beam a trap is triggered. What can they do to enter unharmed?”

- 1.

- What are the ‘big ideas of physics’ which are the focus of this lesson?

- 2.

- How do they relate to what I observed in reality or what I already knew?

- 3.

- Were there times when I found it difficult? What happened when/if I got stuck or did not understand?

- 4.

- Did I actively participate in the lesson? Was I able to explain and present my ideas?

- 5.

- Were the tools, explanations and material used helpful for me to understand? What in particular? What not?

- 6.

- Did the lesson help me to understand how to think as a physicist/mathematician to approach a phenomenon?

- 7.

- Did the lesson help me to think more deeply about the issues addressed?

- 8.

- Is there anything you would like to ask a classmate to explain to you that you are not sure you understand?

4. Discussion

- Topic covered. Light is a relevant topic, suitable to be explored in depth by dedicating time and effort. Indeed, we think that, generally, the scientific theme of a SLU should be among the core topics of the curriculum; thus, this type of planning, which demands a great amount of time and energy spent on design and implementation, can offer an opportunity to reflect on fundamental topics of the subjects involved.

- Story. The narrative must encounter students’ and teachers’ interests. The specificity, from the context and content selected, allows us to reflect on the importance of the narrative frame chosen for the unit. The Lord of the Rings is the particular frame chosen for our case because the teacher knows that it can be of interest to the students in this classroom. Considering the same topic, but implementing it with other students, another background could be a better choice. Therefore, knowing students is important as well as involving the teacher of the class in the design of the SLU.

- Competencies. The competencies we aim to boost by carrying out the unit are modelling and argumentation: we believe that they are particularly suited to be developed with a SLU. However, depending on the learning outcomes selected, other skills could be strengthened by this type of unit, but this requires further investigation.

- Meta-outcomes. If the SLU is considered as a way to promote the awareness of the nature of science, e.g., as in our case with modelling as an argument to be developed between mathematics and physics, take care of the aspects characterising the involved disciplines: e.g., in our design, consider the experimental part for physics and the deduction of laws for mathematics.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

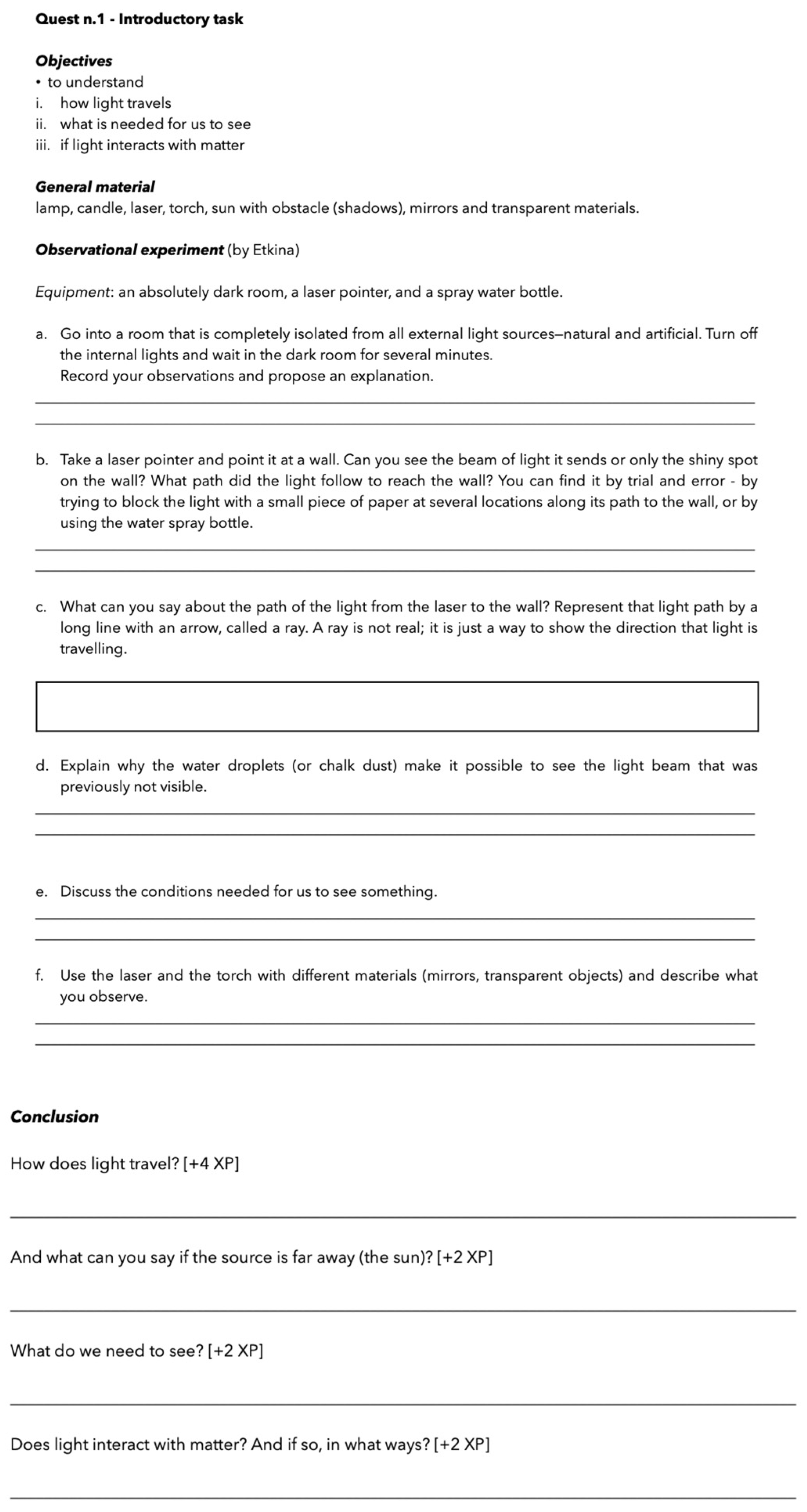

Appendix A

“And you, Ring-bearer,’ she said, turning to Frodo. ‘I come to you last who are not last in my thoughts. For you, I have prepared this.’ She held up a small crystal phial: it glittered as she moved it, and rays of white light sprang from her hand. ‘In this phial,’ she said, ‘is caught the light of Eärendil’s star, set amid the waters of my fountain. It will shine still brighter when the night is about you. May it be a light to you in dark places, when all other lights go out.”Frodo, Sam, Merry, Pippin, Aragorn, Boromir, Gimli, and Legolas leave.A new group of characters arrive at Lórien, and Galadriel now speaks to them: ‘The Fellowship’s members need all the help they can get. The light is important to win against the Dark forces of Sauron.To gain the needed experience to face the challenge, you have some quests to complete. When you will be ready, you can join the Fellowship against the Dark forces of Sauron. So reach them!’But... what is light? And how can we help the Fellowship against the dark forces of Sauron?

After Galadriel speaks to them, they leave in search of the Fellowship. She turns around and invokes the souls of Newton and Huygens to follow the new company to help them (science will help, they do not have magic but they have science).After walking all night trying to reach the company, suddenly our heroes are surrounded by hordes of orcs and the only way to escape is a door in the mountain.Fortunately, the sun is rising, a ray hits the gates, and they open!This happens only on very particular moments. Destiny? Luck? Or perhaps the powers of light... Galadriel was right.Our characters are saved from the orcs! But the dwarves, who are used to the darkness of these places, notice another danger. There are rays to defend the entrance if they interrupt the beam a trap is triggered. What can they do to enter unharmed?

Past the entrance, a fork in the road opens. One road leads downward and one upward. The spirits of Huygens and Newton then decide to intervene. Huygens approaches some of our heroes and suggests going downward; Newton suggests following the other road.They divide. The group following Huygens finds a little lake down the road, and they see beyond it a door.The other group, on the other hand, follows the road, which at one point stops and they see, beyond a small ravine, a door. The jump is not big but the important thing is to be able to open the door.The light is again the key. But they don’t have any source of light. They have to simulate it…but with particles (little balls) or with waves.Newton and Huygens help the characters to better understand the situation.

Both groups manage to get out! And they find themselves in the same courtyard. They tell each other how they managed to cope, comparing their strategies.However, they notice that the courtyard is all fenced off.There is a kind of very small tunnel, it is too small to go through. But at the bottom of it, they seem to see a shimmer, maybe there is a mirror. It seems to be necessary to use light again to get out…

The spirit guides suggest controlling if the conjecture is valid also for the two models.

The company understands the law and they are able to hit the spot using the mirror to get out.

They arrive in a village and need to figure out where to sleep and eat. They hear that the innkeeper has a problem to solve and, having no money, they propose an exchange to the innkeeper: ‘we will solve your problem in exchange for room and board’.

They eat breakfast and watch a spoon in the water, so one of them tells that when he/she washed, he/she saw his/her feet in the basin, they looked strange. Another character says that he/she dropped the soap in the water and to pick it up it was in a different place from where it seemed to him/her…

Our heroes finally reach the Fellowship! But they had to protect themselves with a strange technique: the entrance of the gate seems frozen in a sort of substance similar to glass… They can see the stairs and a plate! It’s a code… Only the worthy can enter.After decoding the message, they understand that if they can hit the switch with the light, they will be able to enter. But they only get one try.They go back and go to a glass artisan so they can do experiments in order to understand how the law of this phenomenon works.

Not understanding the regularity, they go to the library and find writings in human language; only humans can read them.

It is important that the law is correct, they have only one attempt otherwise the mission will be failed.They check with the models by talking to Huygens and Newton…

…and it’s fine.They still check, trying to apply the law to see if it predicts well the behaviour of light when it passes through transparent materials. They have to be really sure before they exploit their attempt. And it works!

They then manage to reach the Fellowship.‘Tell us what you have understood (knowledge is essential for survival). But first, write it. Writing is personal. It represents us when we are absent in space and in time. Writing expresses who we are, even after our lifetime. It makes our knowledge, our personal aspirations and our work for the future visible to others. Writing is the means to explain our ideas to ourselves and to others while preserving our personal experiences and our memories. No one else can do it for you. In this way, writing connects you with yourself. Writing is not fleeting; it is permanent. It is a record of what you wished to communicate at a point in time.Writing enables you to reach many places over time. Keep this in mind, it lives on in the minds of those who read it.Words are powerful, they can be spelt and rich in magic. The universe was created through music and song. Gandalf warned us regarding Saruman, to not let him speak, implying there’s power in the words that he speaks.’

‘Now you have reached the knowledge and the experience to help us.You can build an instrument that can be very helpful for the battle against the Dark Lord: a tool that allows us to see the enemy without making us see ourselves.Moreover, to keep the orcs far away and weaken them, we can use light. The Orcs detest the sunlight and the reason is down to the time and place of their creation. Morgoth bred the Orcs at a time when Middle-earth was still shrouded in darkness, the light of the Two Trees of Valinor unable to reach the furthest corners of the world. As such, the Orcs were literally born in the dark, fighting and thriving in the black of night. When the sun rose over Middle-earth for the first time years after their initial creation, the light traumatised the Orcs, burning and blinding them after so many years shrouded in darkness. And their preference for darkness remains with them. We can exploit this weakness. What mirrors could we use to channel light into the orcs’ hiding places?Then there is another problem. Sometimes, when elves are hit with narrows, they can be poisoned. The substance injected goes into the blood and we should recognize its presence as soon as possible, to prevent the poisoning from spreading throughout the body. How can you determine the concentration of this substance, using light? This substance is similar to human sugar and to test your system you can use water instead of blood. We cannot waste a single drop of blood of our valiant fellows.

References

- Anello, F. Proposta di un framework per la progettazione didattica a scuola. Lifelong Lifewide Learn. 2021, 17, 116–135. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.H.; Green, T.D. The Essentials of Instructional Design: Connecting Fundamental Principles with Process and Practice, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzaci, A. Pratiche riflessive, riflessività e insegnamento. Stud. Educ. 2011, 3, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, C.; Marrongelle, K. Pedagogical content tools: Integrating student reasoning and mathematics in instruction. J. Res. Math. Educ. 2006, 37, 388–420. [Google Scholar]

- Visnovska, J.; Cobb, P.; Dean, C. Mathematics teachers as instructional designers: What does it take? In From Text to ‘Lived’ Resources: Mathematics Curriculum Material and Teacher Development; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 323–341. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, D.; Hollingsworth, H. Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2002, 18, 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, K.; Palm, O.; Palmqvist, J.; Piqueras, J.; Wickman, P.O. Hybridization of practices in teacher-researcher collaboration. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2018, 17, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingerman, Å.; Wickman, P.O. Towards a teachers’ professional discipline: Shared responsibility for didactic models in research and practice. In Transformative Teacher Research: Theory and Practice for the C21st; Burnard, P., Apelgren, B.M., Cabaroglu, N., Eds.; Sense Publisher: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 167–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ligozat, F. The determinants of the joint action in didactics: The text-action relationship in teaching practice. In Beyond Fragmentation: Didactics, Learning and Teaching in Europe; Meyer, M.A., Hudson, B., Eds.; Barbara Budrich Publishers: Leverkusen, Germany, 2011; pp. 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Seel, H. Didaktik is the professional science of teachers. In Didaktik/Fachdidaktik as Science(-s) of the Teaching Profession? Hudson, B., Buchberger, F., Kansanen, P., Seel, H., Eds.; Thematic Network of Teacher Education in Europe Publications: Umeå, Sweden, 1999; Volume 2, pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Haven, K. Super Simple Storytelling: A Can-Do Guide for Every Classroom, Every Day; Teacher Idea Press, A Division of Libraries Unlimited Inc.: Englewood, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sadik, A. Digital storytelling: A meaningful integrated approach for engaged student learning. Educ. Technol. Res. 2008, 56, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, B.R. Digital storytelling: A powerful technology tool for the 21st century classroom. Theory Pract. 2008, 47, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, B.R. The effective uses of digital storytelling as a teaching and learning tool. In Handbook of Research on Teaching Literacy through the Communicative and Visual Arts; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 429–440. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, H. Researching and evaluating digital storytelling as a deep learning tool. In Proceedings of the Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education International Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 19–21 March 2006; AACE: Chesapeake, VA, USA, 2006; pp. 647–654. [Google Scholar]

- Albano, G.; Pierri, A. Digital storytelling in mathematics: A competence-based methodology. J. Ambient. Intell. Human Comput. 2017, 8, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, R. Matematica: Un Problema da Risolvere; Quaderni di rassegna; Edizioni Junior: Azzano San Paolo, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Levrini, O.; Fantini, P.; Tasquier, G.; Pecori, B.; Levin, M. Defining and Operationalizing Appropriation for Science Learning. J. Learn. Sci. 2015, 24, 93–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, M. Children’s Minds; Fontana Press: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Polo, M.; Dello Iacono, U.; Fiorentino, G.; Pierri, A. A Social Network Analysis approach to a Digital Interactive Storytelling in Mathematics. J. e-Learn. Knowl. Soc. 2019, 15, 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Zwickl, B.; Hu, D.; Finkelstein, N.; Lewandowski, H. Model-Based Reasoning in the Upper-Division Physics Laboratory: Framework and Initial Results. Phys. Rev. Spec. Top. Phys. Edu. Res. 2015, 11, 020113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkina, E.; Warren, A.; Gentile, M. The role of models in physics instruction. Phys. Teach. 2006, 44, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, D.; Ektina, E.; Planinsic, G. Implementing an epistemologically authentic approach to student-centered inquiry learning. Phys. Rev. Phys. Educ. Res. 2020, 16, 020148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. A Framework for K-12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca. Schema di Regolamento Recante «Indicazioni Nazionali Riguardanti gli Obiettivi Specifici di Apprendimento Concernenti le Attività e Gli Insegnamenti Compresi nei Piani Degli Studi Previsti per i Percorsi Liceali di cui all’articolo 10, Comma 3, del Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 15 Marzo 2010, n. 89, in Relazione all’articolo 2, Commi 1 e 3, del Medesimo Regolamento.». 2010. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2010/12/14/010G0232/sg (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Morselli, F.; Levenson, E. Functions of explanations and dimensions of rationality: Combining frameworks. In Proceedings of the Joint Meeting of the 38th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education and the 36th Conference of the North American Chapter of the Psychology of Mathematics Education, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 15–20 July 2014; Liljedahl, P., Nicol, C., Oesterie, S., Allan, D., Eds.; PME: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2014; Volume 4, pp. 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Albano, G.; Coppola, C.; Dello Iacono, U. What does Inside Out mean in problem solving? Learn. Math. 2021, 41, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- McTighe, J.; Wiggins, G. Understanding by Design; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rocard, M.; Csermely, P.; Jorde, D.; Lenzen, D.; Walberg-Henriksson, H.; Hemmo, V. Science Education Now: A Renewed Pedagogy for the Future of Europe. European Commission. 2007. Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/resources/docs/rapportrocardfinal.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Black, P.; Wiliam, D. Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 2009, 21, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusi, A.; Morselli, F.; Sabena, C. Promoting formative assessment in a connected classroom environment: Design and implementation of digital resources. ZDM Math. Educ. 2017, 49, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, R.; Rogora, E.; Tortoriello, F.S. La matematica come collante culturale nell’insegnamento. Mat. Cult. Soc. Riv. Dell’unione Mat. Ital. 2017, 2, 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Etkina, E.; Van Heuvelen, A.; Brookes, D.T.; Mills, D. Role of experiments in physics instruction—A process approach. Phys. Teach. 2002, 40, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkina, E.; Van Heuvelen, A.; White-Brahmia, S.; Brookes, D.T.; Gentile, M.; Murthy, S.; Rosengrant, D.; Warren, A. Scientific abilities and their assessment. Phys. Rev. Spec. Top. Phys. Edu. Res. 2006, 2, 020103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkina, E.; Brookes, D.T.; Planinsic, G.; Van Heuvelen, A. College Physics Active Learning Guide, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Students’ Achievement of Content Objectives and Meta-Objectives | |

|---|---|

| LO1 | Can explain the ray model of light (understanding) |

| LO2 | Know and compare models of light, identifying the range of validity, strengths, and weaknesses (understanding and analysis) |

| LO3 | Can explain certain phenomena concerning light–matter interaction, can predict the results of an experiment and mental experiments on light–matter interaction, and can solve problems (understanding and application) |

| LO4 | Can use mathematics to identify, compare, and generalise and formulate laws (geometry, sine function, and basic algebra) to solve problems in optics (application, analysis, synthesis) |

| LO5 | Can use the laws of refraction to recognize and calculate the properties of substances (application) |

| Growth in expository and communication skills | |

| LO6 | Can argue to construct explanations from observations and reflection on experimental evidence, from solutions to a specific problem, and can compare different models on the basis of acquired knowledge (evaluation) |

| Peer collaboration | |

| LO7 | Can listen to the opinions of peers, explain and support peers, collaborate in order to converge on one or more shared solutions, and can compare notes |

| Active participation and responsibility for own learning | |

| LO8 | Actively participates in discussions: responsible for solving problems and responsible for expressing their own thinking |

| Design Principles of a Storytelling Learning Unit | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Write a story that allows for a common thread, keeping in mind a backward design approach, with a focus on the learning outcomes and the assessment criteria. |

| 2 | The narrative must justify the tasks assigned to the students, and the chosen problems the students deal with have to be open to different solutions. |

| 3 | The unit framed upon the storytelling has to follow one or more narrative cycles (e.g., according to the stages of the DIST-M model). |

| 4 | The teacher and students have to all be part of the same story. Creating one’s own character within the story (role-playing game) allows for greater involvement and lowers levels of peer judgment. |

| 5 | Integrate into the story experiential activities in which students can enact what is expected to be learned. |

| 6 | Self-assessment and teacher evaluation of the students’ learning process and learning outcomes, conceived as a formative practice, have to be an essential component of the narration itself. |

| 7 | Provide worksheets that help students to individually express themselves in writing, reflecting also on their own learning process and creating moments of whole-class discussion to encourage oral exposition and co-construction of knowledge with peers and the teacher. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boscolo, A.; Lippiello, S.; Pierri, A. Storytelling as a Skeleton to Design a Learning Unit: A Model for Teaching and Learning Optics. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030218

Boscolo A, Lippiello S, Pierri A. Storytelling as a Skeleton to Design a Learning Unit: A Model for Teaching and Learning Optics. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(3):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030218

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoscolo, Alessandra, Stefania Lippiello, and Anna Pierri. 2024. "Storytelling as a Skeleton to Design a Learning Unit: A Model for Teaching and Learning Optics" Education Sciences 14, no. 3: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030218

APA StyleBoscolo, A., Lippiello, S., & Pierri, A. (2024). Storytelling as a Skeleton to Design a Learning Unit: A Model for Teaching and Learning Optics. Education Sciences, 14(3), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030218