Abstract

This study explores learners’ views and perspectives on the use of the storytelling strategy to study the basics of ecology through the theme “What’s in your river?” at a field and laboratory summer school for thirty-two college students aged sixteen to eighteen years; and in the lecture theatre to teach ecological concepts to nineteen first-year university undergraduate students. The mixed method approach was applied in the study, with the collection of qualitative and quantitative responses. Questionnaires were administered to the undergraduate students with selected questions that relate to the use of storytelling and its application in learning. The undergraduate students were asked the following key questions: did you enjoy the use of storytelling as a learning resource and strategy? how has storytelling helped you in your learning of the basics of ecology? The main findings of the study are that after using storytelling as a learning strategy, 89% of the respondents said it helped them to think more clearly about the story structure; 84% of the students said it helped them to understand the course contents better; 63% stated that it motivated them to learn; and 58% said it was more useful and helpful than the direct dissemination of lectures. Knowledge of river organisms acquired by the students correlated highly (R-square of 0.7112) with the use of storytelling as a tool for learning. The reason why the students enjoyed the use of storytelling is that it is both affective and cognitive. This article will benefit educators as it suggests different ways of thinking in the transformation of information for positive environmental change.

1. Introduction

Storytelling was an important part of my culture and an intrinsic part of people’s way of life. As I grew up and went to school, storytelling was one the ways of learning and conveying important information about the culture, world views, morals, expectations, norms and values [1,2,3]. The function of storytelling has been identified as mediating and transmitting knowledge, wisdom and information across generations. While a person may have forgotten the lesson, they will remember the key elements of the story. Storytelling traditions vary all over the world, yet have many things in common, such as oral narration, moral teachings, use of gestures and repetition [4]. As a student, I was keen to learn about the science beyond the theory and the four walls of a classroom and to learn in such a way that I would know how the knowledge gained relates to everyday living. Studying ecology in the UK and developing an interest in freshwater aquatic invertebrates showed me that each organism’s structure and function tell different stories. Each of them performs a myriad of ecosystem functions, including water purification (e.g., mussels); the processing of organic matter (e.g., caddisfly larva, as shredders); the recycling of nutrients (e.g., through bioturbation affecting sediment geochemistry and benthic–pelagic coupling) [5,6]; the creation of structural habitat complexity that benefits other invertebrate and fish species (e.g., burrowing macroinvertebrates) [7]. Therefore, beyond looking at them physically, their lives are stories in themselves. A high diversity of freshwater invertebrates are insects, given the diverse habitat types available for colonisation, and there have been reports of the global decline of these organisms [8,9]. While reports showed that about 25% of these freshwater invertebrate communities were under threat of extinction (https://reports.peakdistrict.gov.uk/ccva/docs/assessments/wildlife/aquaticinvertebrates.html (accessed on 18 October 2023) due to anthropogenic activities, the decline in insect abundance could have negative consequences for ecosystem function and services. Although these issues were not lost on me because of my studies, I needed a type of knowledge and a means to convey this information. This is so that I can involve others in ways that can provoke change, instill norms and values and inform applied actions in daily living. Given the plethora of challenges faced by freshwater biodiversity, including urbanisation and pollution [10,11,12], I saw a gap in communication between the scientists, the lay public and students in terms of raising awareness and providing essential values needed to protect and conserve our freshwater aquatic invertebrates.

One of the best ways to engage people and to make an idea meaningful is through storytelling, hands-on activities and communication [13].

1.1. Storytelling and Learners’ Engagement

Storytelling can be used to capture the listeners’ attention, communicate information through clear messages and use language that is easily understood through the use of case studies, eyewitness accounts or the testimonials of others [14]. Storytelling brings the teller and audience into a reciprocal process of listening and telling, from which a fresh story of professional meaning and purpose can emerge. This form of communication helps listeners to connect what they hear and practice in their own lives [15]. Therefore, the listeners become conscious beings, build a rapport with the storyteller along with credibility and trust, promote participation and communication [16] and promote the values needed to effect change in society. The connections and relations between humans, and between humans and the animal world, are created through storytelling, and African people’s humanistic philosophy [17] is enshrined in the African concept of “Ubuntu”—which means “I am what I am because of you” [18]. The emotional and cognitive effects of stories [15] delivered by the storyteller could further make listeners engage with the context being presented by the storyteller. According to [3], African storytelling is a powerful pedagogical tool for communicating people’s knowledge and wisdom. It sharpens people’s creativity and imagination, shapes their behaviour, trains their intellect and regulates their emotions. This also aligns with the ecological systems theory of [19], which states that many different levels of environmental influences affect developmental processes, from the immediate surroundings of the individual to nationwide cultural forces. Thus, public engagement initiatives have been shown to promote effective storytelling strategies especially aimed at raising awareness of fundamental issues and where change is needed. By bringing to life the relationship between what is being shared and real-life experiences, all types of people, groups, individuals or institutions, can participate fully and share knowledge with the scientists and other visitors. This form of inclusive participation builds strong, sustainable relationships and strengthens connections within communities through knowledge sharing and gathering, while providing incentives for engaging in conversations [20]. This form of engagement through storytelling is important in communities, as it can give people greater influence over their environment, improve their sense of wellbeing and help them contribute effectively to decision-making processes. These outcomes could lead to a change of attitude and behaviour, and inform positive action and choices facing decision makers [21].

1.2. Emotive and Cognitive Elements of Storytelling

Chinua Achebe, in his book Anthills of the Savannah [22], explains that there are three elements to a story.It entertains, it informs and it instructs. Stories support and reinforce the basic doctrines of a culture. The emotional and cognitive effects of stories impact on the listeners and the storyteller, which therefore makes storytelling a profound tool for engaging a wide range of non-technical listeners [23]. With its ease of comprehension, storytelling could help people to reflect on the different parts of a story that affects them individually, i.e., based on their lived experiences and values. They would then in turn be more inclined to share these experiences with others, ask questions, seek clarification, retain information or include additional information in the story as necessary [14,24,25]. The concept of inclusive public engagement and storytelling aligns with the ideals of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal of including everyone in collective environmental protection. While storytelling is an ancient and powerful practice [26], it has been adapted over the years to occupy different spaces, including lecture theatres and summer schools.

Of special interest to this article is to narrate how the process of storytelling was used to engage diverse groups of students on the scientific theme “What’s in your river?” and to explore their views and the outcomes of the engagement activities. The objectives of the study were to

- raise awareness of using the storytelling format to obtain and process samples, and to identify river organisms and their functions. This objective will be achieved through a summer school designed for and delivered to sixteen- to eighteen-year-old college students.

- communicate knowledge of ecological concepts using lived experiences and curriculum content. This objective will be achieved through a course on introductory ecology to first-year undergraduate students.

- share insights and responses received from the participants.

The present study seeks to answer the following questions:

- What are students’ perspectives regarding the storytelling strategy?

- What are students’ perceptions of using storytelling as a learning resource?

- What is the relationship between students’ knowledge of taught content and the application of storytelling as a learning resource?

2. Methods

The mixed methods research approach was applied in this study, including qualitative responses elicited from diverse groups of participants and quantitative analysis used to describe the relationship between the knowledge acquired by the students and storytelling. The data was analysed using the Microsoft Excel program.

2.1. Activity Structure and Processes

The theme “What’s in your river?” was used as a strategy to capture diverse groups’ interest and engagement through lectures, fieldwork and laboratory activities. Delivery included lecture workshops, field sampling and laboratory analyses of water samples and river organisms sourced from local rivers. These river organisms were displayed on white trays with some water for easy access and visibility, following which the samples were viewed under low-powered microscopes. From the tray, the samples of organisms were placed in Petri dishes with the aid of tweezers, and a few drops of water were added. For each event, participants were welcomed to the space, given a brief introduction to “What’s in your river?” and given a brief explanation of why river organisms are important and why they should be protected. The participants identified each sample using an invertebrate colour Field Studies Council (FSC) fold-out identification chart.

Lecture sessions started with the sharing of personal storytelling based on lived experiences and connected with the contents of the lecture, at different stages.

2.2. First Year Undergraduate Lectures on Organisms and Their Roles in the Ecological Hierarchy

- In order to test the use of storytelling during lectures and to find out how storytelling helped with the learning of ecological concepts, I used the ecological hierarchy topic as a means of introduction. I described the role of river organisms, individuals as part of a population, the community and the broader Earth’s ecosystem. Furthermore, the rights of these organisms to available environmental conditions and resources and their corresponding responsibilities to perform functions and services in the ecosystem were discussed. By using the relevance of social connections in the hierarchy, the rights and responsibilities of each organism were emphasised in relation to the human environment. Before the story was told, the students listened to a personal story of growing up in a hierarchical community where each person looked out for the others and where children were raised by a village, with reference to [27]), and heard how the community connected and provided support.

- A questionnaire was developed which comprised eight questions. These were administered to 19 first-year undergraduate students of Ecology course. I provided the students with eight workshops on aspects of the introduction to ecology. The participants were asked to rate items on a five-point Likert scale (i.e., 5 = Strongly Agree, 4 = Agree, 3 = Neutral, 2 = Disagree, 1 = Strongly Disagree) based on the theme ”Students’ perspectives regarding the storytelling strategy” (rated 7 items) and based on the overall course overview (rated 3 items).

- The participants were asked to answer two items on two scales—Yes or No: I have attended lectures that used storytelling before.

- The participants were asked to rate three items based on a three-point scale (i.e., 3 = all the time, 2 = sometimes, 1 = not at all) for students’ perceptions of storytelling as a learning resource.

- Three open-ended questions were asked as follows: Give reasons why you enjoy listening to stories during the ecology workshops; Give reasons why you do not like the use of stories in the delivery of your ecology lectures; How has storytelling helped you in your learning of the basics of ecology?

- I determined the relationship between students’ knowledge of taught content and the application of storytelling as a learning resource.

2.3. 16- to 18-Year-Old College Students

Thirty-two A-level/sixteen- to eighteen-year-old students participated in a field and laboratory study at a summer school organised at a rural location in the UK. The students, whose parents were selected by a science learned society in the UK from A-Level colleges located in communities that were classified by the Office for National Statistics as below average income, but ethnically diverse [28].

The processes included sampling, selection and identification of organisms, interpretation of results and discussion, observations and interaction. The structure adopted during the workshop was that of a clear beginning, middle and ending. The students completed questions which intended to test what they had learnt and to find out their interests and their motivations for attending the workshop.

2.3.1. The Beginning of the Process: Conversation and Setting the Scene

The session started with a brief introduction and welcoming of the participants to the space. This was followed by a brief lecture with clearly stated aims and objectives: an overview of the day’s activities, the study area, the challenges, the quality and status of the river, the organisms found in the river and the expectations for the workshop, including the collection and identification of river organisms and working in teams. The interlude enabled brief introductions between participants, i.e., demonstrators, students and staff, on what they did as a career, where they came from and what they would like to achieve that day. The students were informed of the risk assessment issues, health and safety factors on site, the protective kit to wear and the need to work as a team.

2.3.2. The Middle: Analysis and Interpretation

This section involved the logistics of traveling the two-mile journey to the stream, the division of the students into groups of three to represent the upstream, midstream and downstream sections of the one-mile river. The students actively participated in the collection of river organisms by using the kick sampling methods and identified the organisms obtained thereby. At a depth of 23 cm, the Hanna meter was used to measure in situ dissolved oxygen (percentage saturation), pH and, conductivity levels (µScm−1). Furthermore, water samples were collected and filtered with a 0.45 µm paper and the filtrate was poured into universal tubes labelled with their group numbers. The water samples collected would be analysed for nutrients including nitrate-N, phosphate-P and ammonia-N. The water samples were analysed using the colorimetric method, i.e., a change in the colour of the water samples was compared with the instructions on the nutrient colour card. The organisms sampled were identified with the benthic macroinvertebrates field guides and the results were interpreted and discussed. Pictures were also taken as evidence of visual participation. Each of the students participated effectively in the sessions. The arrangement adopted in the session included having a clear purpose, the provision of different spaces (laboratory, field) for this group, conversations during the field sampling of organisms, the use of different equipment, teamwork and shared lived experiences.

2.3.3. The End: Take-Home Message

The exercise concluded with a summary of the day’s activities, a step-by-step reiteration of the day’s processes so that the students would have take-home messages. The students shared their feedback and experiences of the day’s activities.

3. Results

This section presents the demography of the first-year undergraduate students (Table 1), findings of the responses to the questionnaire (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5) distributed to the them, to find out what they had experienced with the storytelling and to extract their perception of storytelling as a learning resource (Table 2 and Table 3). These descriptions were followed by the responses provided by the sixteen- to eighteen-year-old students.

Table 1.

Demography of students.

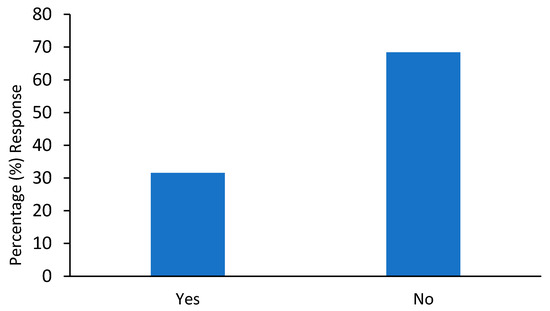

Figure 1.

Percentage of students who had attended lectures that used storytelling before.

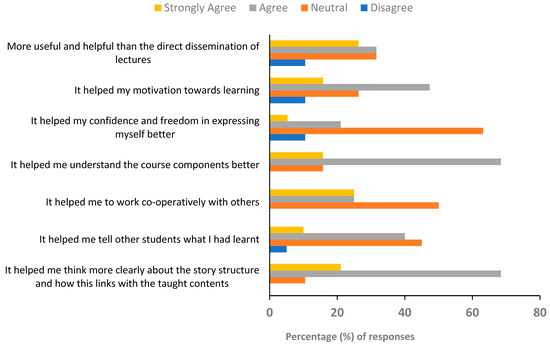

Figure 2.

Responses to students’ perspectives regarding the storytelling strategy.

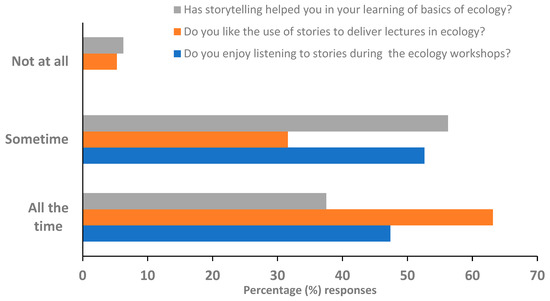

Figure 3.

Responses to students’ perception of storytelling as a learning resource.

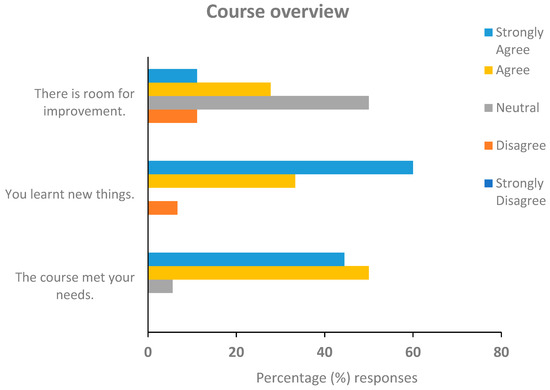

Figure 4.

Responses to students’ overview of the course. The responses were based on percentages using the Likert scale: strongly agree; agree; neutral; disagree; and strongly disagree.

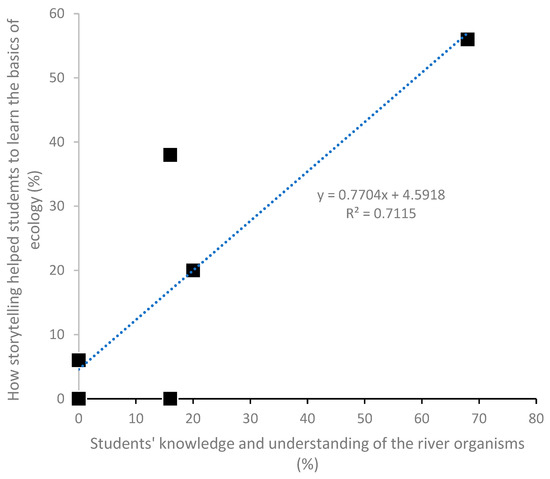

Figure 5.

Students’ responses to how storytelling helped them to learn the basics of ecology (%) and their knowledge and understanding of river organisms (%). The R-square value for the variables was 0.7115, indicating high correlation between the variables.

Table 2.

The reasons why the students enjoyed storytelling during the ecology workshops were grouped into three categories: good pedagogical tool; promotes moral/social and emotional benefits; promotes comprehension and application.

Table 3.

Other perceptions students on the use of storytelling in teaching.

3.1. First-Year Undergraduate Students

The demography of the 19 university-undergraduate students was demonstrated in Table 1 to investigate their views and experience of using storytelling in learning. Of the respondents, 47% were females and 32% were male students.

Question 1: Have you attended lectures that used storytelling before?

Figure 1 showed that 32% (n = 6) of the students had attended lectures that used storytelling while 68% (n = 13) had not.

Question 2: How has the storytelling strategy helped your learning?

Figure 2 showed the responses of students concerning their experience of storytelling as a learning strategy.

- It helped me to think more clearly about the story structure and how this linked with the taught contents: 21% (n = 4) of the students strongly agreed, 68% (n = 13) agreed and 11% (n = 2) were neutral.

- It helped me to tell other students what I had learnt: 10% (n = 2) of the students strongly agreed, 40% (n = 8) agreed, 45% (n = 9) were neutral and 5% (n = 1) disagreed.

- It helped me to work co-operatively with others: 50% (n = 10) of the students were neutral to the experience of storytelling as a learning strategy while 25% agreed (n = 5) and 25% strongly agreed (n = 5).

- It helped me understand the course components better: 68% (n = 13) of the students strongly agreed, 16% agreed (n = 3) and 16% were neutral (n = 3).

- It helped my confidence and freedom in expressing myself better: 63% (n = 12) of the students were neutral, 21% agreed (n = 4) and 5% (n = 1) strongly agreed, while 11% (n = 2) disagreed.

- It helped my motivation towards learning: 47% (n = 9) of the students agreed, 26% (n = 5) were neutral and 16% (n = 3) strongly agreed, while 11% (n = 2) disagreed.

- More useful and helpful than the direct dissemination of lectures: 32% (n = 6) of the students agreed; 26% (n = 5) strongly agreed and 32% (n = 6) were neutral, while 11% (n = 2) disagreed.

Question 3: Did you enjoy the use of storytelling as a learning resource and strategy?

Figure 3 showed that 47% (n = 9) of the students enjoyed listening to stories during the ecology workshops all the time. A total of 63% (n = 12) of the students enjoyed the use of stories in the delivery of their lectures in ecology all the time, while 32% (n = 6) replied that they sometimes did and 5% (n = 1) of them replied that they did not at all. A total of 38% (n = 6) of the students replied that stories helped their learning and understanding of ecology all the time, while 56% (n = 9) replied they did learn sometimes. A total of 6% (n = 1) replied that stories did not affect their learning of ecology at all.

Question 4: Give reasons why you enjoyed listening to stories during the ecology workshops.

Question 7: Has the course met your requirements?

Figure 4 showed that 44% (n = 8) of the students strongly agreed that the course met their needs and 50% (n = 9) agreed, while 6% (n = 1) of the students were neutral. A total of 60% (n = 9) of the students strongly agreed that they learnt new things on the course and 33% (n = 5) agreed, while 7% (n = 1) disagreed. A total of 11% (n = 2) strongly agreed that there is room for improvement, 28% (n = 5) agreed and 50% (n = 9) disagreed, while 11% (n = 2) were neutral.

Question 8. What is the relationship between students’ responses to how storytelling helped them to learn the basics of ecology (%) and their knowledge and understanding of river organisms.

Figure 5 showed a strong linear correlation between the variables. The R-square value of 0.7115 implied that there is a 71% correlation between the students’ knowledge and understanding of river organisms and the use of storytelling as a means of learning. The Mean ± Standard Deviation for students’ responses on how storytelling helped them to learn the basics of ecology was 20 ± 25.57, and 20 ± 28 for students’ knowledge and understanding of river organisms.

3.2. 16- to 18-Year-Old Students

The processes of introduction, sampling and identification of the invertebrates and the processing of their samples at the laboratory as part of a team provided mediums of sharing and engagement. These exercises contributed immensely to the interpretation of the results and discussion. The energetic contributions provided a space for the students to share their stories and lived experiences. These processes fostered a deeper understanding of why these little organisms were important within the scope of the food chain. The outcome of the discussions provided a narrative with which the students developed their own narrative features in the context of storytelling.

The feedback comments shared by the participants at the end of the exercises showed that they all enjoyed the workshop. When they shared their personal experiences, the students stated:

I feel a part of a community.

I feel at home in the space.

We could speak and be listened to, and not judged.

I am more confident about myself.

I enjoyed collecting data and interacting with nature.

Hands on! Interesting to see invertebrates from silt.

Working as a team! Maybe needed a bit more time for the discussion and interpretation of nutrients.

Identifying the invertebrates was interesting and new.

I liked the kick sampling, had to do with a group and shared our view.

Invertebrate identification because I like seeing new things.

Field trip was my favourite because it was interactive.

I enjoyed it all. Very informative! Thank you.

I will consider studying freshwater ecology at the University.

The motivation for participating at the summer field course for most of the students were largely social, in addition to educational and career development. Most of them wanted a chance to travel and to visit new places and meet new people; it was a scholarship; to explore the possibility of studying ecology at a higher educational institution; to meet potential role models. Others felt they were making their parents and guardians proud. Some of the students were reluctant to share stories about their home locations for obvious reasons, e.g., gun crime; nothing to see or to report on where I come from; it is all buildings and people; I would rather not think about it.

4. Discussion

All the participants who engaged with the theme “What’s in your river?”, including the processes of observation, collection, identification and interpretation, or who listened to the experience and stories related to ecological concepts, enjoyed the experience and learnt a few things about organisms and their functions. Human knowledge and complex information, when embedded through storytelling, generates more attention and engagement. The stakeholders build shared understanding and trust [14,16] as a result. A high correlation between the use of storytelling and the knowledge of river organisms gained by the students showed that the science was communicated in a clear, easier-to-understand and practically relevant way [13].

Hands-on activities were shown to influence the participants’ interests in “What’s in your river?” Hands-on learning, which implies learning by experience and practice, could serve as a more realistic form of effective learning for adolescent students who might be less motivated to study science [29]. With reported declines in students’ interest in the sciences [30,31], the use of quality hands-on activities in lecture rooms and field sites could be used as a strategic tool to rekindle interest in science and promote positive attitudes that could be beneficial to students’ interest and learning. All participants had the opportunity to observe, engage with each other, listen to me and ask questions. Through all these activities and this connectedness, trust is built [14]. Trust is essential if better study interventions are to be developed [32]. Interventions based on the power of storytelling could inform the nurturing of positive behavioural and systemic change in any community, which impacts a vision for a just society where inclusive and collective environmental protection is enabled [33].

In order for learners’ interests to be sustained for a longer time, learning by listening and enjoyment are fundamental. The authors of [34] observed that emotions have a substantial influence on the cognitive processes in humans including perception, attention, learning and problem solving. To promote enjoyment, the storytelling format, which included diverse oral, physical and hands-on activities, created opportunities for learners’ abilities to develop, while the conversations between the participants enhanced common affiliations, interests and knowledge development. Thus, far from being a mere source of entertainment, the storytelling process helped to sharpen people’s creativity and imagination, to shape their behaviour, to train their intellect and to regulate their emotions [3].

The communal participatory experience, style and structure of the teaching sessions align with African storytelling traditions, which start with an introduction and end with some moral lessons [4,17,18,22,35]. All the venues chosen for the activities created a welcoming atmosphere that fostered conversations and enabled participation [20]. Through conversations, discussion and connections with other people in welcoming teaching spaces, participants are helped to openly express feelings of despair, optimism, support and hope. The authors of [36], through the project Performing Sciences, argued that by employing strategies from the Arts sector, science educators could facilitate opportunities for pleasure and for collaborative and social learning.

Furthermore, the introductory session which sets the scene enabled the participants to engage with others during the middle and closing sessions, when lessons and take-home messages were collated. The attention and enthusiastic responses elicited from the participants in the feedback revealed the levels at which they have been captivated by the exercises and the oral renditions in the process of field sessions, laboratory sessions and lectures.

The learners had positive perceptions of the use of storytelling as a learning resource as it allowed them to relate taught contents to real life issues, they felt a part of a community/at home, they worked as a team and they needed more time for the discussion and interpretation of their data. The students stated that storytelling enabled them to work in collaboration with others. Collaboration is a key aspect of using storytelling as a pedagogical strategy [24] and makes the process a success. This form of knowledge acquisition through collaboration creates social interactions which help maintain recipients’ interest in the story contents over a long period of time, and thereby enables prolonged engagement with the story content [37].

While the emotions, connections and, passion expressed by the engaged participants will impact indelibly on their minds [15], the exercises initiated a motivation for learning and for change, i.e., to protect their rivers and organisms, and to create their own stories. The feelings of pleasure in learning could help lay people reflect on how they can contribute their quota to environmental and river protection, and in small ways leave some ecological footprints [38]. This, therefore, suggests a call to be more intentional with the delivery of scientific information and to connect the content with real life issues. The enjoyment, interest and confidence demonstrated by the participants revealed that storytelling promotes not only social and emotional benefits, but also comprehension and application, and helps retention in long-term memory [37]. By keeping teaching fresh and interactive, storytelling serves as a good pedagogical tool with many intrinsic benefits [14]. The process of learning using stories not only addresses the affective component, i.e., to make the recipients more open to new experiences, but is also more likely to approach novel information.

5. Conclusions

This study’s aim to raise awareness of using the storytelling format to communicate knowledge of ecological concepts was achieved. Storytelling was delivered through a myriad of activities including creating a welcoming, safe space and by using aspects of the curriculum to share stories and lived experiences. The students’ perspectives regarding the benefits of the storytelling strategy and its use as a teaching and learning resource were highlighted in the benefits. These include motivation to study, comprehension and knowledge retention and a feeling of belonging to a community.

Funding

The project was funded by an award received from the University of Manchester under the Open Access funding No. 215092.

Informed Consent Statement

All responses provided and presented in this study were anonymous and participants cannot be identified.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the science learned society and the first year students who participated in the study and to the reviewers of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Gbadegesin, O. Destiny, Personality and the Ultimate Reality of Human Existence: A Yoruba Perspective. Ultim. Real. Mean. 1984, 7, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidou, O. Gender, Narrative Space, and Modern Hausa Literature. Res. African Lit. 2002, 33, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinyowa, K.C. The Sarungano and Shona Storytelling: An African Theatrical Paradigm. Stud. Theatr. Perform. 2001, 21, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuwe, K. The African Oral Tradition Paradigm of Storytelling as a Methodological Framework: Employment Experiences for African Communities in New Zealand. In Proceedings of the 38th AFSAAP Conference: 21st Century Tensions and Transformation in Africa, Deakin University, Victoria, Australia, 28–30 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, K.J.; Probert, P.K.; Jeffries, M. Conservation of Aquatic Invertebrates: Concerns, Challenges and Conundrums. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2016, 26, 817–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macadam, C.R.; Stockan, J.A. More than Just Fish Food: Ecosystem Services Provided by Freshwater Insects. Ecol. Entomol. 2015, 40, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covich, A.; Palmer, M.; Crowl, T. The Role of Benthic Invertebrate Species in Freshwater Ecosystems—Zoobenthic Species Influence Energy Flows and Nutrient Cycling. Bioscience 1999, 49, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.S.; Ngo, H.T.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.A.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Chan, K.M.A.; et al. Pervasive Human-Driven Decline of Life on Earth Points to the Need for Transformative Change. Science 2019, 366, eaax3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D.L.; Dudgeon, D. Freshwater Biodiversity Conservation: Recent Progress and Future Challenges. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 2010, 29, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medupin, C. Distribution of Benthic Macroinvertebrate Communities and Assessment of Water Quality in a Small UK River Catchment. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medupin, C.; Bark, R.; Owusu, K. Land Cover and Water Quality Patterns in an Urban River: A Case Study of River Medlock, Greater Manchester, UK. Water 2020, 12, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medupin, C. Spatial and Temporal Variation of Benthic Macroinvertebrate Communities along an Urban River in Greater Manchester, UK. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundin, A.; Andersson, K.; Watt, R. Rethinking Communication: Integrating Storytelling for Increased Stakeholder Engagement in Environmental Evidence Synthesis. Environ. Evid. 2018, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrom, M.F. Using Narratives and Storytelling to Communicate Science with Nonexpert Audiences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13614–13620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, S.; Hettinger, A. Storytelling: A Natural Tool to Weave the Threads of Science and Community Together. Bull. Ecol. Soc. Am. 2019, 100, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burk, N.M. Empowering At-Risk Students: Storytelling as a Pedagogical Tool. In Annual Meeting of the National Communication Association Office of Educational Research and Improvement(OERI); Educational Resources Information Centre (ERIC): Seattle, WA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chinyowa, K.C. More than Mere Storytelling: The Pedagogical Significance of African Ritual Theatre. Stud. Theatr. Perform. 2000, 20, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandela, N. Long Walk to Freedom; Little, Brown: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; ISBN 9780349106533. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development; Sage Publications Ltd: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McGinn, M.M. Inclusive Outreach and Public Engagement Guide; Race and Social Justice Initiative: Seattle, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, H.M.; Goldman, E.; Mcleod, K.L.; Sievanen, L.; Balasubramanian, H.; Cudney-Bueno, R.; Feuerstein, A.; Knowlton, N.; Lee, K.; Pollnac, R.; et al. How Good Science and Stories Can Go Hand-in-Hand. Conserv. Biol. 2013, 27, 1126–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achebe, C. Anthills of the Savannah; William Heinemann Ltd: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Joubert, M.; Davis, L.; Metcalfe, J. Storytelling: The Soul of Science Communication. J. Sci. Commun. 2019, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, C.; Michael, C.; Poynor, L. Storytelling as Pedagogy: An Unexpected Outcome of Narrative Inquiry. Curric. Inq. 2007, 37, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckillop, C. Storytelling Grows up: Using Storytelling as a Reflective Tool in Higher Education. In Proceedings of the Scottish Educational Research Association Conference, Perth, Scotland, 24–26 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.; Schlaepfer, P.; Major, K.; Dyble, M.; Page, A.E.; Thompson, J.; Chaudhary, N.; Salali, G.D.; MacE, R.; Astete, L.; et al. Cooperation and the Evolution of Hunter-Gatherer Storytelling. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reupert, A.; Straussner, S.L.; Weimand, B.; Maybery, D. It Takes a Village to Raise a Child: Understanding and Expanding the Concept of the “Village”. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 756066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics. What Are the Regional Differences in Income and Productivity? Explore Economic Inequality in the UK with Our Map. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/visualisations/dvc1370/ (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Holstermann, N.; Grube, D.; Bögeholz, S. Hands-on Activities and Their Influence on Students’ Interest. Res. Sci. Educ. 2010, 40, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, P.; Hasni, A. Analysis of the Decline in Interest Towards School Science and Technology from Grades 5 Through 11. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2014, 23, 784–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steidtmann, L.; Kleickmann, T.; Steffensky, M. Declining Interest in Science in Lower Secondary School Classes: Quasi-Experimental and Longitudinal Evidence on the Role of Teaching and Teaching Quality. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2022, 60, 164–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moezzi, M.; Janda, K.B.; Rotmann, S. Using Stories, Narratives, and Storytelling in Energy and Climate Change Research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, M.; Johnson, C.; Fox, D.; Phartiyal, P. Scientist-Community Partnerships. A Scientist’s Guide to Successful Collaboration; Centre for Science and Democracy, Union of Concerned Scientists: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tyng, C.M.; Amin, H.U.; Saad, M.N.M.; Malik, A.S. The Influences of Emotion on Learning and Memory. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achebe, C.; Innes, C.L. Contemporary African Short Stories; Heineman: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- French, S.; Mulhern, T.D.; Ginsberg, R. Developing Affective Engagement in Science Education through Performative Pedagogies: The Performing Sciences. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Math. Educ. 2019, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, M.; Garsoffky, B.; Schwan, S. Narrative-Based Learning: Possible Benefits and Problems. Communications 2009, 34, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shernoff, D.J.; Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Schneider, B.; Shernoff, E.S. Student Engagement in High School Classrooms from the Perspective of Flow Theory. In Applications of Flow in Human Development and Education: The Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi; Csikszentmihalyi, M., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).