1. Introduction

It is undeniable that we live in a highly technologized society. The use of the Internet and digital social platforms has reconfigured how public opinion is created (information, communication, and expression) and has altered the roles traditionally assigned to politicians, media, and citizens.

In fact, in recent years, political and social leaders have used these media to launch communiqués, create news, and even incite mobilisations. In parallel, there has been a wave of civic and social uprisings to influence policies, where the use of digital and social media has been a key aspect of fostering and demonstrating citizen engagement [

1,

2,

3].

To this end, for example, social networks are full of hashtags that launch various media campaigns for social or political causes, which are then used mainly by young people with a high level of digital and socio-civic skills. Likewise, they are increasingly involved as creators and contributors of online content [

4,

5,

6]. The use of technology, especially among young people, provides new possibilities not only for retrieving information but also for creating, sharing, communicating, and fostering critical thinking. The latter is becoming exponentially more necessary due to the effects of misinformation and data manipulation [

1,

7].

It is worth noting that, according to the data from the National Institute of Statistics (2018) [

8], people between 16 and 24 years of age use the Internet, and the main activity they perform is participation in social networks. In this sense, technological development has also implied transformations in the forms of communication and media literacy in educational contexts [

9].

Digital competence encompasses the ethical, responsible, creative, critical, and safe use of information and communication technologies (ICTs), while simultaneously having the ability to adapt to a new set of knowledge and attitudes needed in this era to be competent in a digital environment. In addition, the development of socio-civic competences is a combination of attitudes, knowledge, and social, emotional, and cognitive skills aimed at interacting with the public and expressing solidarity and interest in solving community problems. Moreover, like digital competences, it involves critical reflection to be active participants in a community and in decision-making processes [

3,

10,

11].

Digital citizenship is an ever-expanding concept and is already defined as the ability to locate, access, use, and create information effectively and to act actively, critically, sensitively, and ethically in digital environments, being security conscious, and acting responsibly. However, alongside this, there must also be a reflection on citizen literacy as a right within the educational policies aimed at equal opportunities [

12].

This highlights the growing importance of ICTs in various social spheres, including academia, and the need for teacher training through the development of digital and citizenship competences [

2,

13]. A breakthrough in the identification of digital competences for teachers in the EU context came with the introduction of the European Framework of Digital Competences for Citizenship (DigComp), a tool developed by the European Commission [

14]. This framework not only became a reference for the development and planning of digital competence initiatives at the European level and in member states but also served as a prelude to the DigCompEdu framework.

The DigCompEdu framework is specific to digital competence for teachers at all levels of education, from early childhood to higher and adult education. This includes general and vocational education, special needs education, and non-formal learning contexts [

15]. It identifies twenty-one competences and organises them into five areas. In addition, it establishes eight levels of depth to define the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to be digitally competent. This structured approach provides a clear framework for the assessment and development of teachers’ digital competences in the educational context [

16].

In the Spanish context, the Common Framework for Digital Competence in Teaching (INTEF, 2017) has been established as the reference context for the diagnosis and improvement of teachers’ digital competences. On 16 May 2022, the Directorate General for Evaluation and Territorial Cooperation published the Agreement of the Sectoral Conference on Education on the reference framework for digital competence and teaching [

17]. It referred to the importance of digital technologies in all areas of society as being key in teaching and learning processes. In addition, the first article of the document included an agreement between the Ministry and the Regional Education Ministries to use the digital competence framework as an essential instrument for improving their educational policies in relation to the digital competence of teachers. Furthermore, it was established that the curriculum should foster the development of technical competences, global awareness, and other complex skills, such as networking, critical perspective, and online political activism [

18,

19].

In this sense, in the same way that the LOE (2006) [

20] takes into account the influence of the Key Competences for Lifelong Learning developed in that year by the European Commission [

21], the LOMLOE of 2020 includes a revision of the Key Competences of 2018, recognising the existence of a general use of ICTs, which makes their integration into education of great importance. From this perspective, and in line with the key role of digital competences in human development, the preamble calls for a change of approach that recognises the social and personal impact of technology [

22], thus expressing the widespread importance of information and communication technologies (ICTs) and the need for their integration in education.

Furthermore, in primary education, as in subsequent stages, the LOMLOE adds to its regulatory framework the concern for the risks derived from the use of ICTs. In other words, it considers the development of digital competence in teachers and pupils not only in terms of the access and use of technologies but also as the prevention of inappropriate use of ICTs and safety training. Therefore, attempting to define digital competences from a purely instrumental perspective limits not only their definition but also their implications for the daily lives of citizens who use technology. For this reason, it is necessary to link it to citizenship competence, another key competence, which “contributes to enabling students to exercise responsible citizenship and participate fully in social and civic life, based on an understanding of social, economic, legal and political concepts and structures, as well as knowledge of world events and active engagement in sustainability and the achievement of global citizenship” [

22].

In line with this, the various decrees establishing the organisation and curriculum of the different types of education point out and call for the incorporation of information and communication technologies in the curricula, the appropriate use of these technologies, and the promotion of digital competence in all areas of education. They also empowered the head of the competent regional ministry for education to issue as many provisions as necessary for the development and implementation of their provisions (see Decree 101/2023, of 9 May, which establishes the organisation and curriculum of the Primary Education stage in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia) [

23]. For this very reason, it is necessary to try to understand how to educate young people in participation and how to improve education for digital citizenship through the development of socio-civic competences [

24,

25], especially in the field of social sciences.

Although there is a prolific literary field related to digital skills and specifically linked to tool development, more work remains to be performed on digital age skills, how technology is used for social and civic actions and engagements, and how digital skills affect youth participation and society as a whole [

3,

26,

27,

28].

Within a conceptual model, the integration of digital competences in teacher education is based on the need to prepare future teachers to face the challenges of an increasingly technological educational environment. The theory of digital pedagogy stresses the importance of harnessing technologies to improve teaching and learning processes.

However, digital competence refers to the ability to use, accept, and critically evaluate information and communication ICTs. Therefore, it is not limited to technical knowledge but encompasses the ability to apply this knowledge in varied contexts, adapting to the changing demands of the digital society [

11]. This competence involves digital literacy, the handling of digital tools and platforms, the ability to assess the credibility of online information, and the development of communication and combination skills in digital environments.

The development of the ethical paradigm supports the idea that educators play a crucial role in the formation of digitally accountable and aware citizens. From a pedagogical point of view, models such as the project approach and problem-based learning provide contexts conducive to the development of digital and citizenship competences. Citizenship competence refers to an individual’s ability to participate in society effectively and responsibly. It involves an understanding of citizenship rights and responsibilities and a focus on democratic values. It also encompasses skills such as participation in democratic processes, informed decision-making, respect for diversity, and the ability to address social problems [

26].

In the digital context, citizenship competence extends to digital citizenship, which involves the ability to participate ethically and reflectively in a digital society. This includes understanding online rights and responsibilities, privacy management, constructive participation in online communities, and the ability to critically evaluate digital information [

27].

Constructivist theory supports the idea that students, and in this case, future teachers, learn most effectively when faced with authentic and contextualized challenges. Both sociocultural theory and citizenship education emphasize the importance of training future teachers in digital citizenship skills that focus on the ability to participate effectively and ethically in the digital society, including aspects such as privacy, online safety, and critical evaluation of information on the web.

From these assumptions, the Didactics of Social Sciences plays a fundamental role because it prepares teachers to conduct their practice by making reasoned decisions about the best way to teach social knowledge to achieve useful and meaningful learning for students and society. Let us remember that this discipline approaches teaching and learning from specific problems, linked to the nature of the different subjects of study, their contents, and methods, Ih entail particular difficulties and potentialities [

29]. In addition, the proposed readings and activities will contribute to the development and implementation of mechanisms of analysis, critical reflection, and creativity, which are essential for proper professional practice within the field of education [

30].

One of the fundamental goals of Social Science Education is to train democratic citizens [

31] capable of living democratically with others, actively participating in the social, cultural, economic, and political life of the community around them, seeking to improve it, and fully exercising their citizenship [

32,

33]. Thus, considering the society in which we live and the needs it imposes, the teaching of social sciences must be useful for understanding today’s world and for developing social and civic commitment [

34].

To understand a process as complex as the teaching of social sciences, it is essential to reflect on the crucial role of teacher training as a necessary element for transformation. The main challenge lies in finding a new teaching model that integrates the new social reality, emerging teacher training, and profiles, as well as new professional competences [

35,

36,

37].

Undoubtedly, in relation to the methodological principles that currently underpin teaching, we assume that 21st century teachers must base their teaching actions on the understanding and analysis of diverse realities, as well as on a critical interpretation of how to approach them. Beyond the personal interest in developing their digital competence, primary education teachers have a crucial responsibility in the development of students’ technological skills at these stages [

38].

The development of digital competeIce is not only limited to the mastery of devices and applications; it also implies the responsibility to use them in a pedagogical way, promoting collaborative work, respect for people and the environment, and responsible, critical, and safe use of technology. It is also concerned with preserving personal and socio-familial privacy, as well as the protection of personal data, among many other aspects [

39,

40].

Citizenship education constitutes the perspective that gives meaning to the various dimensions of historical and social knowledge. To achieve this, it is essential to acquire skills in communication, decision-making, and social action [

34,

41]. Thus, we argue that values’ education involves cultivating respect for one’s own life and that of others, as well as fulfilling responsibilities as an integral element of citizenship, thus contributing to the construction of democratic processes.

Therefore, our professional practice must be connected to the civic and democratic principles that govern our community and should guide us all to contribute to the betterment of society. Against this background, it is imperative to create solutions that allow for an accurate diagnosis of the situation and consequently to rethink many of the approaches to teaching practice. It is essential to shed light on the causes and, as far as possible, establish a model and processes that contribute to positively reshaping this educational context [

42,

43].

However, to acquire competences, understood as the knowledge and skills that guide you to be successful in a job, it is necessary to develop prior skills (or specific capacities) that, once assimilated, through experience, learning, and practice will provide the adequate foundations to be competent to achieve specific objectives in particular contexts. They involve the successful application of skills in practical, real-life situations. It could be argued that learning skills is the stepping stone to acquiring competence.

In general, little attention is paid to skills’ learning, although in our view, it is an essential component of education and human development. It should not be forgotten that skills are fundamental components of competencies, and both are essential in education to prepare students (and teachers) with the necessary capabilities to face challenges in life and work. While skills focus on specific abilities, competencies address the ability to apply those skills effectively in broader and more complex contexts.

Therefore, skills not only impact personal success (self-efficacy, self-confidence, and self-esteem) but also contribute to building a citizenship with competences to form a stronger and more resilient society (with values related to empathy, solidarity, commitment, and effective communication).

In these pages, an initial investigation is carried out to determine and analyse the state of digital and socio-civic skills of training teachers of primary education, based on Didactics of Social Sciences, taught in the Faculty of Education Sciences at the University of Granada (Spain). In this way, a series of indicators are studied to serve as a starting point for a profound exercise of reflection with the aim of improving the preparation of future teachers for the important challenges that lie ahead in the 21st century, as an essential element for the necessary social transformation.

However, this is not a process that is completed in a day, a few months, or a few years [

44] because the university teaching function is a complex activity that involves a set of skills and competences to achieve a reasonable level of success. For this reason, with this work, we do not aim to achieve magic formulas that provoke an immediate reaction in students regarding the acquisition of competences (something evidently impossible), who also carry with them erroneous concepts and acquired practices that are difficult to eradicate, but to establish a starting point to provoke synergies in the teaching staff of the subject of Didactics of Social Sciences, so important in these matters, which will help to improve joint working methodologies from year to year in order to achieve a more adequate preparation of the teachers of the future.

3. Results

The results were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25. First, a descriptive statistics analysis was performed for the Likert scale variables of the questionnaire, including the establishment of the mode and variance ratio.

It should be pointed out that, as expected, the age of the respondents corresponds perfectly to the standards established for the preparation of the questionnaire, since the majority of students in the Didactics of Social Sciences subject in the academic year 2023–2024 are between 18 and 29 years old, with the vast majority being between 18 and 20 years old (78.8%), followed by those between 21 and 23 (16%) and students between 24 and 26 years old (3.2%).

In the first part of this analysis, the focus is on the dimension related to the perception of their digital skills (see

Table 2).

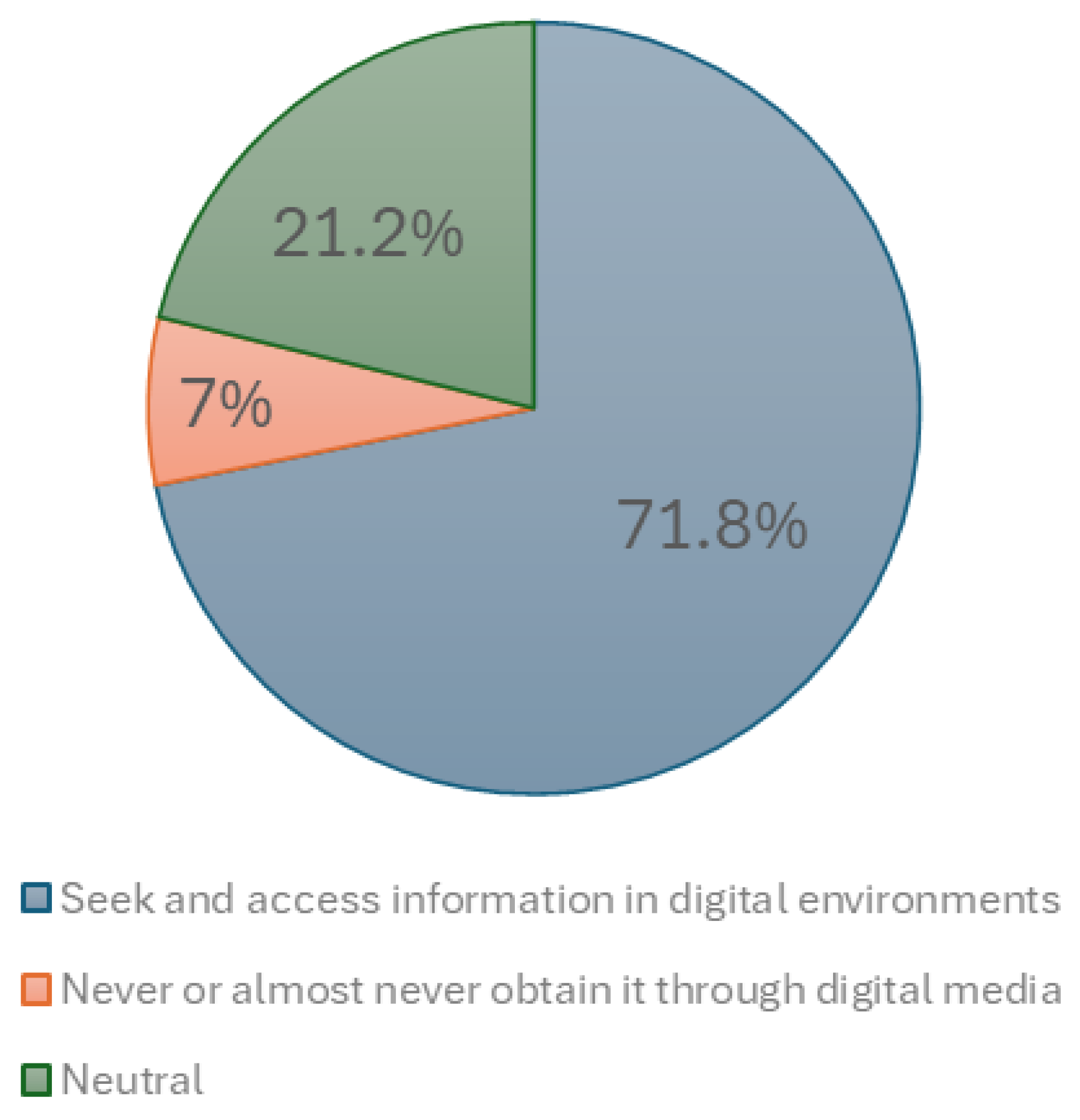

In relation to the sub-dimension linked to the management and use of information and data, most participants in the study seek and access information in digital environments (71.8%), while only 7% never or almost never obtain it through digital media. It is also noteworthy that 21.2% were neutral to the question (see

Figure A1 in

Appendix B).

They also said that they understand the information they get from the Internet (62.2%) (32.7% were neutral), and along the same lines, they also understand the information and messages transmitted by the media (61.5%), with 33.3% giving a neutral answer. According to the information provided, few (7.7%) do not critically evaluate the media (or do so very little), while approximately half of the respondents (56.7%) do so quite a lot (32.1%) or always (24.4%). Of the total number of participants, 35.9% were neutral.

In addition, 62.6% always or almost always used dialogue to resolve conflicts in digital environments, making decisions (74.3%), and solving problems using relevant information (74.3%).

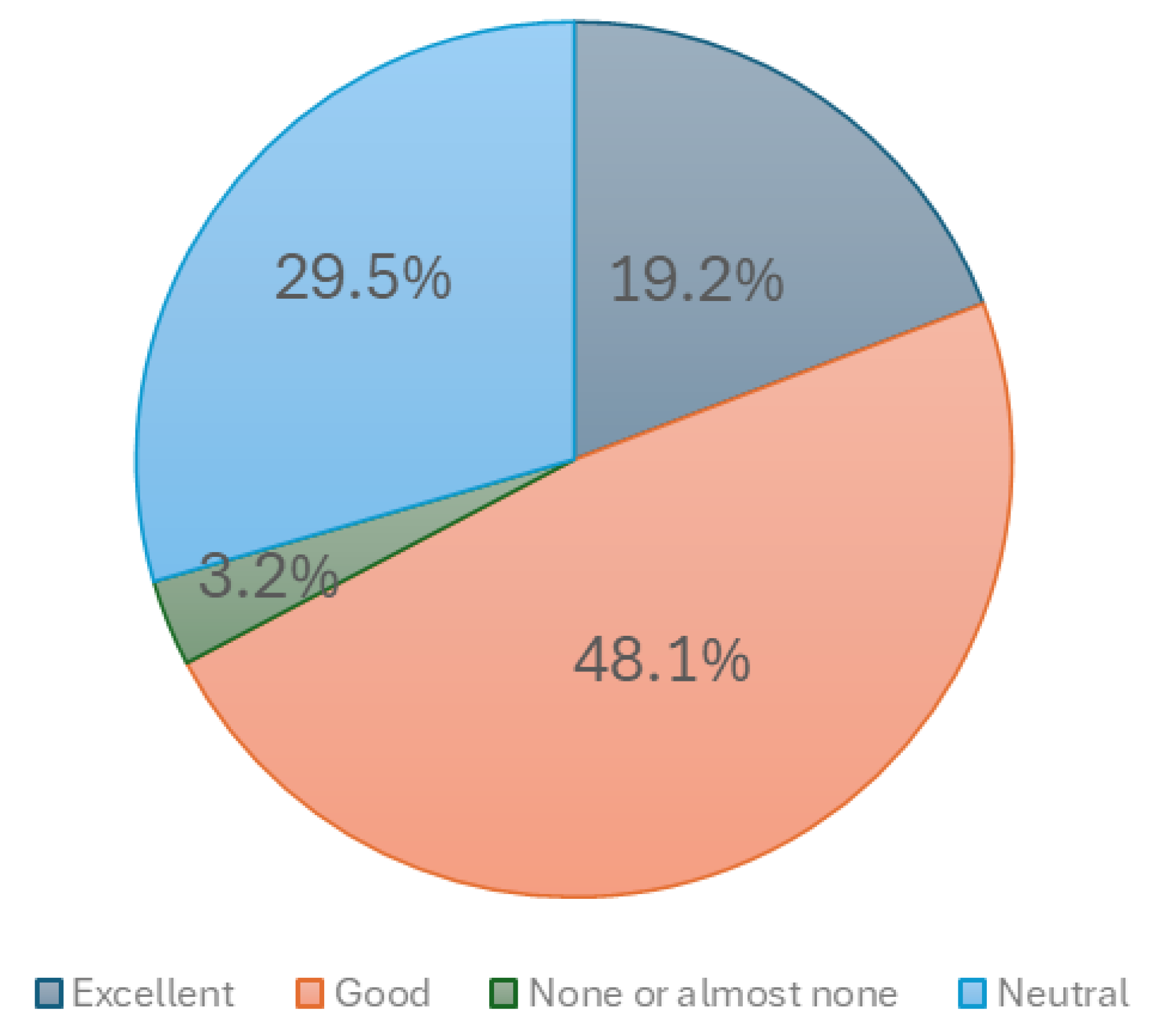

The mode of information and data management and use is 4, indicating that the “medium-high” category is the most frequent among students. Regarding the sub-dimension related to communication skills, the participants considered that they have excellent (19.2%) or good (48.1%) communication skills. On the other hand, 3.2% of people had none or almost none of these skills and 29.5% were neutral (see

Figure A2 in

Appendix B).

The vast majority (53.2%) know or perfectly know (28.2%) how to communicate in different ways (images, text, videos, etc.) and transmit constructive messages in different environments regularly (42.3%) or very often (23.1%). It is also very common for them to communicate their ideas to people they know (81.4%). Only 3.2% of respondents said that they almost never do this.

The mode of the sub-dimension related to communication skills is 4, indicating that the category medium–high is the most common among students’ responses.

Regarding their skills in digital content creation, the data obtained indicate that they share information and content with other people through electronic devices frequently (33.3%) or very frequently (35.9%), while only 13.5% never or almost never do so.

To this end, they use different digital content to express themselves in digital environments (64.7%), and to this end, not so many modify or include digital content habitually (30.1%) or very habitually (17.9%) in their publications on social networks.

Thirty-four percent were neutral on this issue. The mode of digital content creation is 5, the highest of all categories. Regarding the sub-dimension related to the management and security of information and digital content, few respondents said they do not use or hardly use tools to store and manage information (10.2%).

On the other hand, there are many who know (37.2%) or know perfectly (39.7%) different ways to create and edit digital content (videos, photographs, infographics, texts, animations, etc.) and can transform (41%) or transform perfectly (28.2%) the information and organize it in different digital formats.

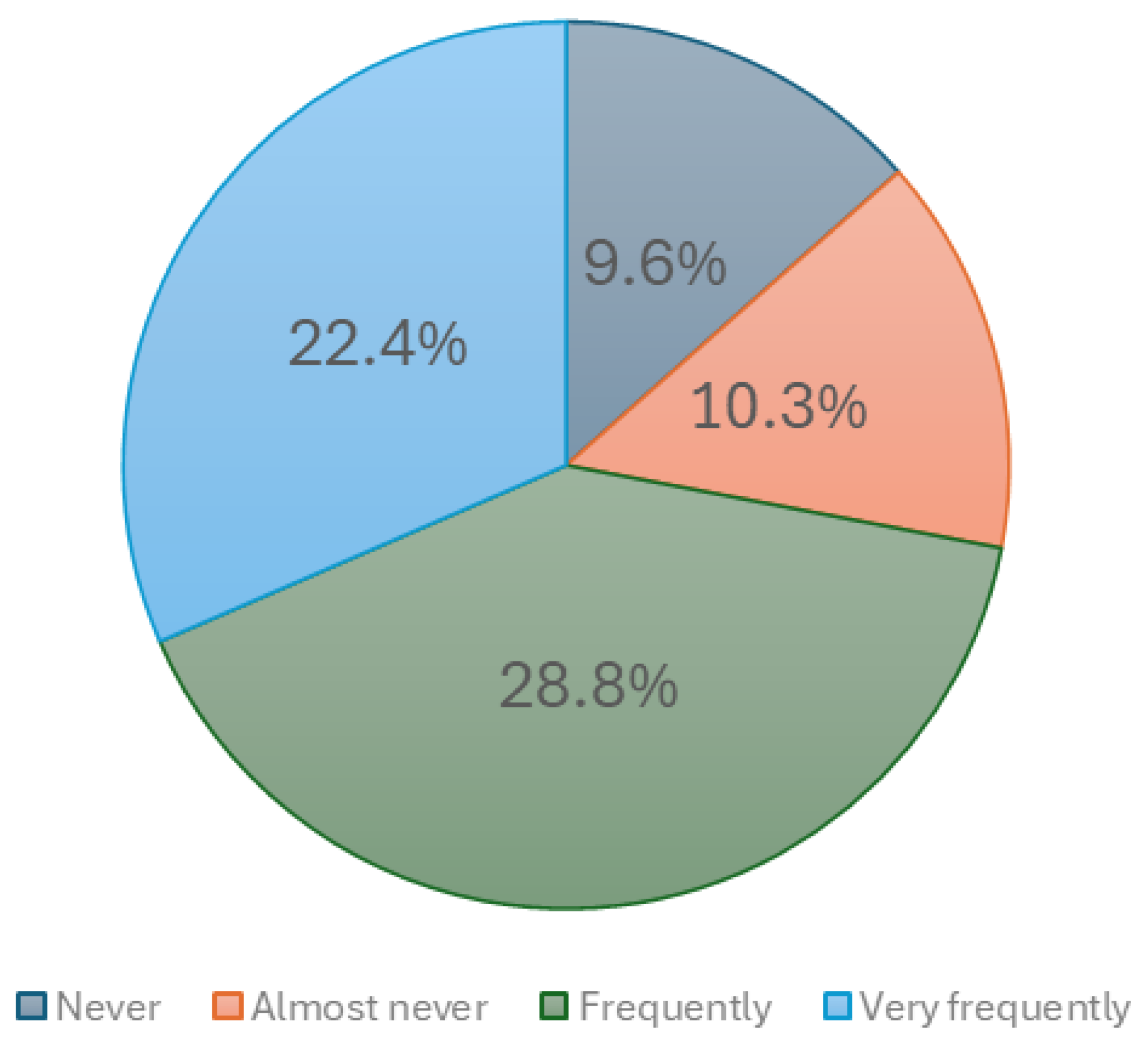

However, according to the data obtained, they do not excessively share materials created by themselves or others (never: 9.6%; almost never: 10.3%; frequently: 28.8%; and very frequently: 22.4%) (see

Figure A3 in

Appendix B). Similarly, most configure their devices to protect their privacy (78.9%) and are careful with their personal information (85.9%).

This time, the modes of management and security of information and digital content were 4 and 5, respectively, indicating that the highest categories were the most frequent among the students’ responses.

Regarding the last dimension, ethical and digital responsibility, the participating students expressed that they are careful (39.1%) or very careful (42.3%) that their messages do not bother others. Only 4.4% expressed that they never or almost never pay attention to these issues. Participating students develop and publish digital content considering the rights of individuals (63.4%) and intellectual property rights (57%), although 33.3% were neutral on this issue.

Regarding the latter, 14.7% never or almost never take it into account when making their publications, and likewise, in the case of developing new digital content, 20.5% do not say where or from whom the information comes from. However, in general, they do think about the possible consequences before performing a digital activity (uploading a photo, commenting, etc.) (75.7%). Regarding the mode of this sub-dimension, ethical and digital responsibility, the most common is 4, indicating that the “medium-high” category is the most frequent among students.

In the second part of this study, the focus is on the dimension related to the perception of civic skills (see

Table 3). With regard to the sub-dimension linked to social and political attitudes and behaviour, 31.4% of the students participating in this study affirmed that they are politically involved, while 26.9% were neutral on this question.

Furthermore, they consider it important (37.2%) or critical (35.9%) for young people to know about political life (political parties, electoral programmes, electoral procedures, etc.), while 6.4% think that it is not important.

Also, most young people frequently or very frequently interact with other people through social networks (79.5%), with just over half using digital technologies to exercise their citizenship (51.9%). On this point, 31.4% opted for a neutral stance. At the same time, 25.6% said that they participate in digital activities organised by other people or entities, while 49.4% said that they do not do so. Twenty-five percent gave a neutral response. Among the information collected, 26.6% said that they keep up to date with political and social news, while 19.9% confirmed that they are not or almost not at all. It is worth noting that the majority (40.4%) were neutral on this question.

To keep up to date with what is happening, 37.2% have applications that are configured to keep up to date with the news and 31.4% do not have apps for this purpose.

In addition, 21.2% search frequently or very frequently (33.3%) for information on the Internet about social and/or political issues, while 16.7% of students hardly ever do so or never (5.8%).

On the other hand, 19.9% confirmed that they are part of a social networking group that discusses political issues, while 65.4% said that they do not participate in any group. Similarly, 30.1% of respondents belong to a social networking group that discusses social issues, whereas 52% do not. Finally, 11.5% confessed to being very engaged and taking action on social issues, while 34.6% said they are engaged. In this sense, 39.1% responded neutrally.

In turn, 14.7% responded that they were not committed and did not act to solve social problems, and 39.1% responded neutrally. The mode of social and political attitudes and behaviour was 3, indicating that the “neutral” category is the most frequent among the participants. On the other hand, concerning the digital empathy of future primary school teachers, the students participating in the survey stated that they help other people (82.7%), are able to put themselves in other people’s shoes (86.5%) (only 0.6% say this is difficult), and respect others (93.6%).

Moreover, in general, they explained that they inform themselves before commenting on an issue (80.7%), that they listen to other people when they present opinions contrary to their own (88.4%), and that they politely argue their opinion (84.6%).

Finally, 77.6% avoided behaviour that is harmful to their health and well-being on social networks and 3.2% do not.

On the other hand, the mode of digital empathy is 5, indicating that it is the highest category among those presented. Regarding the sub-dimension of social and digital engagement, students answered that they mostly adopt and defend an opinion on different issues (85.9%), listen to both sides of a disagreement (84.6%) (almost never, 1.3%), consider the opinion of others (89.7%), and try to listen to opinions that differ from their own before making decisions (82.7%) (not at all, 1.9%). They also confirmed that they work towards a diverse and multicultural society (63.1%), while 7% do not and 28.8% responded neutrally.

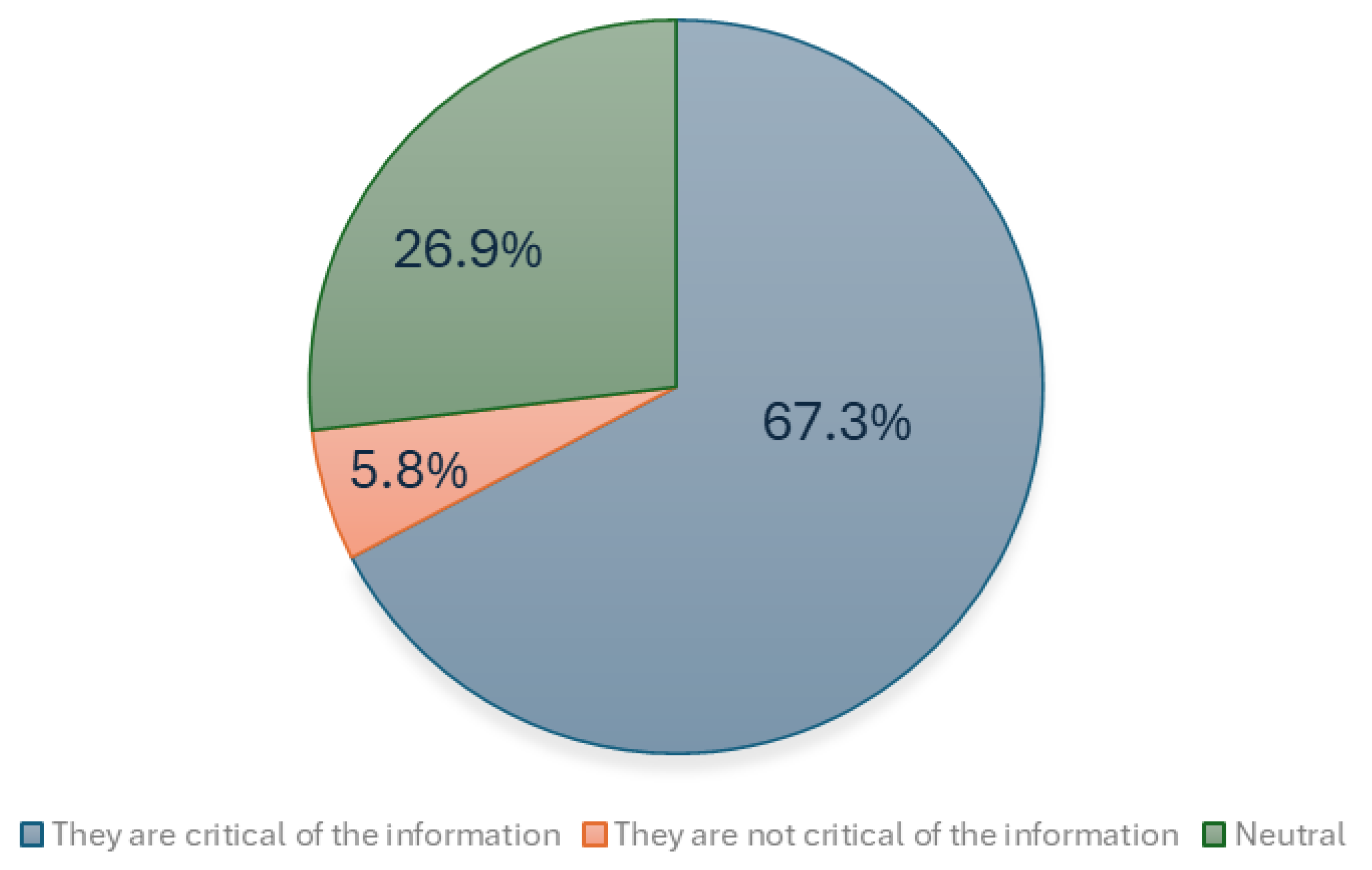

In this case, the mode of the sub-dimension social and digital engagement is 5, the highest category among all of them. When asked about critical thinking, the participating students expressed that they are critical of the information they have (67.3%) (5.8% were not and 26.9% were neutral) (see

Figure A4 in

Appendix B) and make judgements about the new information they receive (62.9%) (9% were not and 31.4% were neutral).

In addition, they identified harmful behaviours that may affect their health and well-being on social networks (62.9%) (neutral, 26.3%) and reflected on whether a digital environment is a safe space (73.8%) (not at all, 6.4%). The mode of critical thinking is 4, indicating that the “medium-high” category is the most frequent among students.

When asked about their democratic attitudes, their responses show that, in general, they value and defend democratic values (freedom, equality, justice, solidarity, tolerance, etc.) (75.5%), with only 2.5% not valuing or defending them.

Likewise, they are concerned about fake news and disinformation on the Internet (79.9%), whereas 5.8% are not. Finally, 80.7% avoid having discussions in digital environments and 3.2% do not.

In this case, the mode of democratic attitudes is 5, indicating that the highest category is the most common in the responses. Regarding the last sub-dimension (pro-social behaviour), students consider volunteering to be a fundamental activity for young people (71.2%) (3.9% think it is not and 25% answered neutrally) and criticise and reject any kind of violent behaviour (78.2%), and 3.2% say they do not (18.6% answered neutrally).

There is also a majority that appreciates the importance of accessing media in different formats (press, radio, television, Internet, etc.) (66.6%) (7.7% do not appreciate it and 25.6% were neutral). Finally, the mode of the sub-dimension on pro-social behaviour is 4, indicating that the “medium-high” category is the most frequent.

4. Discussion

Most students in the subject of Didactics of Social Sciences in Primary Education at the University of Granada access information from digital environments, mainly the Internet and social networks, just as young university students do [

56]. These data confirm the work of Arab and Díaz [

57], who state that it is influenced by personality traits, disciplines of study, gender, and the type of digital action. Furthermore, young university students tend to make intensive use of a limited set of services and sources [

58], which contradicts the concept of “digital natives” due to their presumed technological literacy [

59].

Note that a good part of them understand the information they receive in general, but it seems that a critical evaluation of everything that comes from the Internet and the media does not prevail. The latter conforms to the conclusions of Catalina-García et al. [

56], which argue that it is intensive users who make more extensive use of these digital services and place a higher degree of trust in digital information. This casts doubt on their critical thinking and problem-solving skills, as argued by Gutiérrez and Cabero [

60].

This is a major conceptual issue, as the intersection between digital and citizenship competences is found in the notion of digital citizenship, which implies the ethical and accountable use of technology to participate meaningfully in society. Holistic education theory supports the integration of these competencies, recognizing the need to develop well-rounded and socially engaged individuals. The interconnectedness of these competences is manifested in the ability to use technology as a tool for citizen empowerment, social problem-solving and effective participation in online communities [

3].

Similarly, several studies indicate that youth currently have an optimal level of technological skills, including the use of devices such as computers, tablets, and mobile phones, as well as participation in social networks. However, they lack a critical attitude towards the media [

39]. From the theoretical framework, a critical attitude toward the media can be realized through several dimensions involving the ability to analyse, evaluate, and reflect on media information. The ability to break down and examine media content into its fundamental components, identifying key messages, narrative approaches, and argumentative structures enables individuals to learn how information is presented, what elements are highlighted, and how narratives are constructed in the media [

7].

This leads to a strengthened ability to discern the reliability and credibility of information sources in the media and helps to distinguish between accurate and biased information, appropriately contextualising and determining its relevance. It also favours the recognition of the authority of sources, avoiding the uncritical acceptance of a single point of view, thus promoting a more complete and balanced understanding of the issues [

1]. This conceptual framework is linked to the development of cognitive and emotional skills that enable people to interact in an informed and critical way with the media, promoting a more active and conscious citizen participation.

For their part, future primary school teachers emphasise, as is the case with young people their age, that they understand that they have good skills related to information management and communication competences [

61], especially in more basic tasks [

62].

In reality, they use social networks and the Internet to communicate with people they know, and they can do so in a variety of ways, although they do not modify digital content. On one hand, as the most specialised studies respond, the greatest difficulties are associated with content creation, creativity, or innovation [

60,

63], although many of the respondents confirm that they know how to create and edit digital content and can transform and organise information in different formats.

However, it is important to highlight that several studies [

39,

64,

65] support the differences between students’ perceptions of their digital competence levels and actual skills. This issue has been referred to as competence idealisation [

66]. These differences may be due to their daily use of technology and a positive attitude towards it [

67].

Nevertheless, they are not digital creators, and everything seems to indicate that these skills are not exploited because they do not feel the need to put them to use, since the training teacher makes utilitarian use of the Internet and social networks and does not find in them a resource for developing their creativity or showing social or political commitment. Related research also proposes a conceptualisation of youth in terms of digital competences and civic participation. At one extreme, there is a small group of young people who are able to acquire these skills but, for various reasons, do not use them autonomously to engage in civic activities [

68].

The data analysis and the results of the study indicate that the most prominent digital competence among the participating students was related to safety. This is also affirmed by other studies on future teachers [

66], who exercise an important responsibility in digital environments with empathy and digital commitment. Future teachers should be responsible and develop ethical behaviour when using the Internet or social networks, taking care with their actions to disturb other users and bearing in mind the consequences of their digital publications. However, it is worth noting that, as the students themselves have stated, they usually use digital environments to communicate with acquaintances and friends, which always leads to a more cordial relationship with those with whom they have an affinity, even previously, outside the Internet.

According to the information collected, a large proportion of the undergraduate students surveyed considered the rights of individuals and intellectual property rights when acting in digital environments. In our opinion, these results are the result of answers with a social desirability bias, where students have not expressed their true opinions or behaviour; since in our experience, they are not always so respectful of these rights when preparing their coursework, in which, among other issues, they must cite the authors and works consulted accordingly. Perhaps much more in line with reality are the responses of the third of respondents who say that they do not stop to think about these issues when they are in digital environments. This is also in line with the study by Gabarda et al. [

39], which states that young people have a low level of awareness of copyright and licencing. It is important to work on this issue with the aim of building a conceptual basis that helps to realize the dynamics between creators, their works, and how they can be used and shared within society, balancing authors’ rights with access to and dissemination of culture.

It is particularly interesting to note that most participants are neither socially nor politically involved, although it is striking that they do state that it is important for young people to be aware of political life. Along these lines, they do not participate in organised digital activities, few have applications configured to follow current information, nor are they part of groups that comment on or debate political and social issues. It should also be borne in mind, as mentioned above, that most of the time young people spend in digital environments is spent socialising with their friends and peers.

In this analysis, the future teachers, although they do not act to reinforce and disseminate them, value democratic values very positively (except for a small percentage which should make us think). In this line, they show little or no interest in the consumption of non-news media. A key question can be explored to obtain data on the reasons why they do not feel attracted by information about what is happening in their community or in the world, as confirmed by Catalina-García et al. [

56].

In reality, it is a question of behaviour that goes beyond the digital environment, since, as most of them confirm in their replies, they are not committed to or do not act in relation to social or political issues. Consequently, they do not exercise citizenship when they are on the Internet or social networks, which is in line with their habitual use of these new technologies. This type of behaviour is closely linked to the disaffection of young people towards institutions and political life and, consequently, a decrease in the levels of democratic participation. Instead, a goal of compulsory education systems should be to ensure that learning democratic values and political participation is promoted to prepare people for active citizenship [

69].

As can be seen, they know, value, and aspire to a fully democratic society, but the aim of education must be to promote reflection and critical thinking, which is the basis for a commitment to responsible action to improve society and the world around them. These objectives should also be addressed in digital environments, which are becoming increasingly important and influential in our daily lives. Both the Internet and social networks are no longer tools that serve only to communicate with friends and family or passively contemplate what is happening there, but it is necessary to use these instruments to develop digital citizenship in a free, dignified, critical, and creative way. Therefore, digital literacy education is closely related to social and civic skills, and it is increasingly necessary. Both digital and citizenship competences are essential skills in contemporary society, and their integration into educational training aims to prepare individuals to be informed and ethical participants in an increasingly digital and complex world.

Therefore, training teachers in technology is of relevance to ensure the effective development of students’ digital skills. Only teachers who are digitally competent can educate citizens capable of facing the social, political, and economic challenges of a knowledge society [

70].

As teachers of Social Science Didactics, we will insist on the implementation of active methodologies that take advantage of the potential of digital environments to actively involve students in understanding and tackling social and political problems, while promoting essential digital skills. These include procedures that work with technological tools and encourage active participation in digital environments closely. It is increasingly necessary to develop collaborative online projects, where students can work together in identifying, researching, and presenting solutions to social and political problems; to create educational blogs where students can analyse, research, and discuss current issues, as well as consult current news through traditional media in digital format (press, TV, documentaries, etc.); to integrate the use of social networks and social media in the learning process; to integrate the use of social networks or online discussion forums, so that students can discuss issues, share their own resources, and collaborate on projects related to social and political problems; as well as encourage the creation of educational podcasts where students research, interview experts, and present solutions to specific problems in their environment.

This paper cannot end without identifying some of its limitations. First, the use of anonymous, perception-based questionnaires carries some risks, such as insincerity, with the risk of social desirability bias, where respondents may answer in a way that reflects what they consider socially acceptable rather than expressing their true opinions or behaviours; lack of conscientious responses, where it is impossible to determine whether the respondent has adequately reflected on the questions before answering, which may affect the quality and accuracy of responses; and differences in understanding and interpretation, which may lead to inaccurate responses due to misunderstandings. Overall, the instrument seems suitable for drawing initial conclusions on the issues that have been addressed.

Another limitation is the selection of the sample rather than its size, as this was a purposive sample based on the ease of access to the participants. Also, derived from the latter, is the lack of generalisation of the results obtained to other contexts, such as other Andalusian or Spanish universities, which would serve to compare the results.

The last point is linked to the time of data collection. In this sense, this study was conducted during class hours (face-to-face) and on a voluntary basis; therefore, the data obtained were related to the attendance received on those days. Simultaneously, the questionnaire was administered at the beginning of the academic year, which may have affected the arguments that many may have put forward due to their lack of teaching experience and lack of relationship with the educational field, as they have not yet begun their work experience in primary schools.